(also called) : chivatitos , chivitos , chivatos, lengua de pájaro (birds tongue), lengüitas, Hierba de San Nicolas, barbas de San Nicolas, berros, excacahue, señorita, barba de chivo, tsikuarini, quelite poblano, xubatoti (Matlatzinca), Rock purslane, Red maids, Fringed Red maids

Variously identified as

Calandrinia ciliata (Linares etal 2017) (syn Calandrinia caulescens) (Yanovsky 1936)

Calandrinia micrantha (Castillo-Juárez etal 2009)

- called khutash (xutash) by the Chumash peoples (1)

- called púúchakla by the Luiseño peoples (2)

- called barba de chivo or tsikuarini by the Purépecha (3)

- The Chumash are a Native American people of the central and southern coastal regions of California, in portions of what is now San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura and Los Angeles counties, extending from Morro Bay in the north to Malibu in the south.

- The Luiseño or Payómkawichum are an indigenous people of California who (at the time of the first contact with the Spanish) inhabited the coastal area of southern California, ranging from the (present-day) southern part of Los Angeles County to the northern part of San Diego County, and inland almost 50km.

- The Purépecha are a group of indigenous people centred in the northwestern region of Michoacán, Mexico and live mostly in the highlands of central Michoacán, around Lakes Patzcuaro and Cuitzeo.

Calandrinia is a large genus of flowering plants and contains the species known as purslane (verdolagas)(1). It includes around 150 species of annual and perennial herbs. Plants of this genus are native to Australia, western South America (as far south as Argentina and Chile), Central America, and western North America. The genus was named for Jean Louis Calandrini, an 18th-century Swiss botanist.

Larousse Cocina (1) (an excellent resource) notes that chivatitos is a wild plant of the Portulacácea family that is native to Mexico. It has a limited time in which it can be accessed (as do many of the “wild” quelites) and is available at markets during the rainy season (from May to September). They note that only the aerial parts of the plant (i.e. the leaves and stems) are eaten and that the flavour is stronger when they are eaten fresh. Larousse notes the species as being Calandrinia micrantha.

- Larousse also notes C.micrantha as being called Patitas de pájaro (bird feet) or by its Náhuatl name ixitotol

One author (Padilla Loredo 2015) notes that chivatitos is a quelite that has “commercial importance” and places it in a category of other wild foods with similar importance (papaloquelite, huitlacoche and berros silvestres (wild watercress).

Jordan (etal 2002) notes of Chivitos (identified as Calandrinia micrantha) that it is a plant that milperos have expressed an interest in recovering as it has largely disappeared due to the use of modern commercial herbicides in the milpa. Vieyra-Odilon & Vibrans (2001) note Chivitos as being Calandrinia micrantha Schltdl) and that it was purchased in the mercados of Ixtlahuaca (1), where it grew in the area until the early 1980’s, at which time it seemed to simply disappear (due to the beginning of herbicide use?). Another paper (Viesca-González etal 2022) notes that in the mercados of Toluca (2) chivatitos is one of twelve (3) quelites that are “collected, traded, and consumed” commercially (although in low quantities and only when in season – if applicable) by low income farmers and those on subsistence (4) diets. “People used to collect them from their milpa, but now they are found only in fields located in the mountains and a long walk is necessary to get them” (Viesca-González etal 2022).

- Ixtlahuaca de Rayón (just called Ixtlhuaca) is the municipal seat and 5th largest city in the municipality of Ixtlahuaca north of Toluca in the northwest part of the State of Mexico. and lies about 32km from México City. The name Ixtlahuaca comes from Náhuatl and means plains without trees.

- Toluca, officially Toluca de Lerdo, is the state capital of the State of Mexico as well as the seat of the Municipality of Toluca. Toluca is located 63 kilometres southwest of Mexico City and about 37km south west of Ixtlhuaca

- included in this “dirty dozen” are quintoniles (Amaranthus hybridus), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), cenizo (Chenopodium berlandieri) and huauzontles (Chenopodium berlandieri subsp . nuttalliae)

- subsistence : noun : the action or fact of maintaining or supporting oneself, especially at a minimal level. The poorest of the poor.

500 kilometres south of Toluca in the Mixteca Alta of Oaxaca quelites were collected in the municipality of Santo Domingo Tonaltepec as part of a Mexican Agrobiodiversity project cataloguing the quelites of the milpa in this area. Chivitos popped up in the survey where locally it was known as “quelite poblano”

Damian Barajas (2019) notes in her thesis that the Purépecha people call C.micrantha barba de chivo or, in an older tongue, tsikuarini. Sánchez Ramos (2017) says that in the town of Tetlatzinga, located in the Municipality of Soledad Atzompa (in the State of Veracruz, Mexico) C.micrantha is known as quelite de Borrego or by its Nahuatl name Ichkakilitl.

As of 2022 you could find chivatitos in the mercados of Toluca being sold in 500g bags and reaching prices of between 10 and 16 pesos per kilogram (with the best prices to be found at the Central de Abasto de Toluca market). The herb is placed in the same category as papaloquelite in that it is consumed “fresh in salads, or used as garnishes, complements, or dressings” (Viesca-González etal 2022).

The plant can also be cooked and eaten in a manner similar to spinach and (in Guatemala) is said to be one of the best wild pot herbs (Standley & Steyermark). The seeds are naturally high in oils (Moerman 1998) and were collected and ground into a meal (1) which could be eaten raw or cooked (Yanovsky 1936) (Kunkel 1984) or eaten like pinole (2)( Moerman 1998).

- the edible part of any grain or pulse ground to powder. You expect a “meal” to be slightly oily and not a dry powder.

- Pinole seems to describe any of a variety of forms of parched or roasted corn, ground into a flour and combined with water and some spices or sugar. It can be made into a drink, an oatmeal-like paste, or baked to form a more-portable “cake.”

Orozco and Javier (2018) in their book “La cocina tradicional en la cultura otomí” (Traditional cooking of the Otomi culture) (1) have published a recipe of a quelites and queso Oaxaca salad. See further down for a recipe.

- Otomí, a broad designation referring to various distinct indigenous groups and languages that have existed from pre-Hispanic times through the present, principally in the areas west and north of the Valley of Mexico. It is a designation that includes the peoples whom the Nahuas called the Otomí, Mazahua, Matlatzinca, and Ocuilteca, particularly numerous in the Valley of Toluca, plus other groups in what are now the states of México, Hidalgo, Querétaro, and San Luis Potosí, including the southern Chichimec zone. There are also pockets known to exist in Puebla, Tlaxcala, Michoacán, Jalisco, and elsewhere. The Otomí had strong ties to the Tepanecas, imperial rulers based in the city of Azcapotzalco, who were defeated by the Mexica and Acolhuas in 1430.

In Guatemala (1) chivito (2) is a tolerated weed of the milpa and is associated with corn, lettuce, cauliflower, wheat and potato crops. Farmers allow it to grow so that it can be sold at local mercados where it is relatively easy to find. Here the herb is known variously as Hierba de San Nicolas, barbas de San Nicolas, berros, excacahue, and señorita. It is eaten fried with tomato or envueltas en huevo (in omelettes). Azurdia (2016) notes that “In Mexico this species continues to be consumed by indigenous people, but it has already been incorporated on a small scale in the salads of the dominant socio-economic class”. Its bad enough that quelites are being forgotten due to the stigma of being food for the poor or the indigenous but how do we feel when they are gentrified by the “dominant socio-economic class”? A desire for the plant will however encourage its cultivation and prevent its loss. Hopefully, along the way, we can be educated about the herbs origin and the reason for its importance. Azurdia proffered no medicinal information for the herb.

- mainly in the western part of the country, such as the departments of Quetzaltenango, San Marcos, Chimaltenango and Sololá

- Calandrinia micrantha

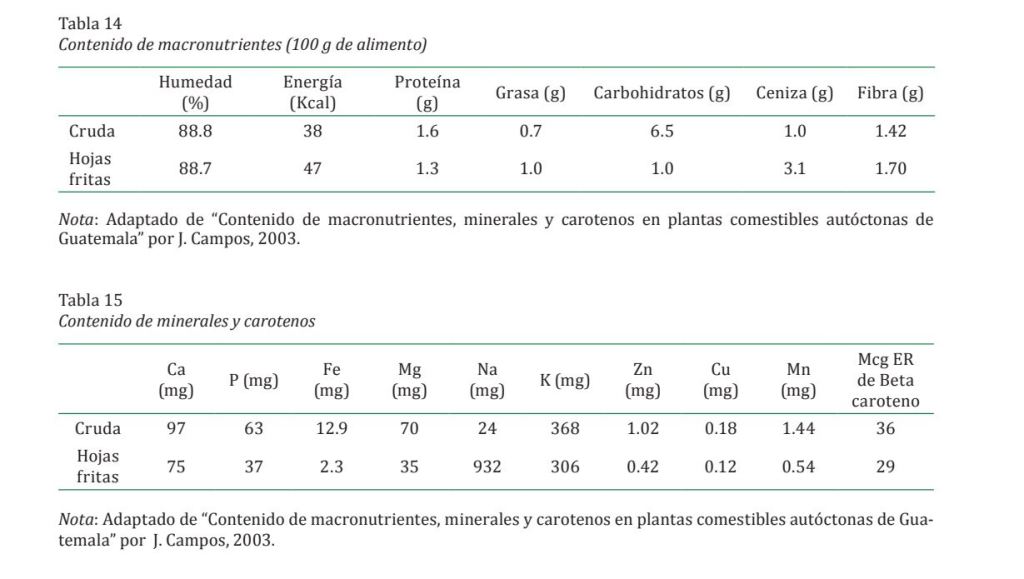

Azurdia (2016) did however publish nutritional data for the herb.

Calandrinia balonensis

In the area of Coober Pedy in Australia the aboriginal people know a plant called Nyurngi (1) which is from the Calandrinia species (Calandrinia balonensis) whose seeds they use in a similar manner to the Chumash people. The seeds are collected and used as a foodstuff in times of hardship (2). The small black seeds can be eaten raw or ground into a paste that is rich in protein and fat, but gathering the seeds in useful quantities is labour-intensive. Parakeelya was an important food for Aboriginal people in Central Australia. (3) The Pitjantjatjara (4) people would (and presumably still do) eat the whole plant (flowers, leaves and roots) and would steam the leaves, roots and stems before eating them (whose flavour was described as pleasantly acidic). It was also noted that European settlers and explorers made use of this plant by “seasoning it well and serving it with a white sauce”. The roots can be consumed raw or cooked. This differs from the use of the species in Mexico where I have found no indication that the roots of chivatitos were eaten (this does not mean that it was not done though). The semi succulent stems were also eaten raw (for their high moisture content) during dehydration emergencies (See WARNINGS). It is noted that the Aboriginal people of Australia did not use this plant medicinally (1).

- This plant is also called Parakeelya. https://warndu.com/blogs/first-nations-food-guide/pretty-parakeelya

- One reason for the plant not being a reliable foodsource (of seeds) is that the seeds ripen gradually over a period of time. This means that there will not be a lot of seed available at any one time (from any given plant)

- This plant occurs throughout Central Australia: it is prolific in the arid regions west of the Great Divide spreading out across central Australia into Western Australia. The two areas I mention (Coober Pedy and Uluru) are about 700kms apart.

- Who call themselves Anangu (the people) and represent the largest “language group” of Australian aboriginal peoples.

(near Uluru – Ayers Rock in Central Australia)

WARNINGS : this plant is high in oxalic acid content. Oxalic acid is considered to be an “anti-nutrient” as it can lock up certain nutrients in food (preventing their absorption) and, if eaten in excess, can lead to nutritional deficiencies. It is, however, perfectly safe in small amounts and its acidic taste adds a nice flavour to the dish. Cooking the plant will reduce the quantity of oxalic acid (just dispose of the cooking water). People with a tendency to rheumatism, arthritis, gout, kidney stones and hyperacidity should take caution if including this plant in their diet since it can aggravate these conditions. See my Post Xocoyoli : The Sour Quelite for the possible dangers of consuming foods high in oxalates.

The WARNINGS for Parakeelya are the same…..To reiterate…..People with a tendency to rheumatism, arthritis, gout, kidney stones and hyperacidity should take caution if including this plant in their diet since it can aggravate these conditions. This is also particularly relevant if you are using the plant as a survival source of water intake. Your hydration levels are already very low and this will increase the oxalate content in your bloodstream and exacerbate the conditions mentioned above.

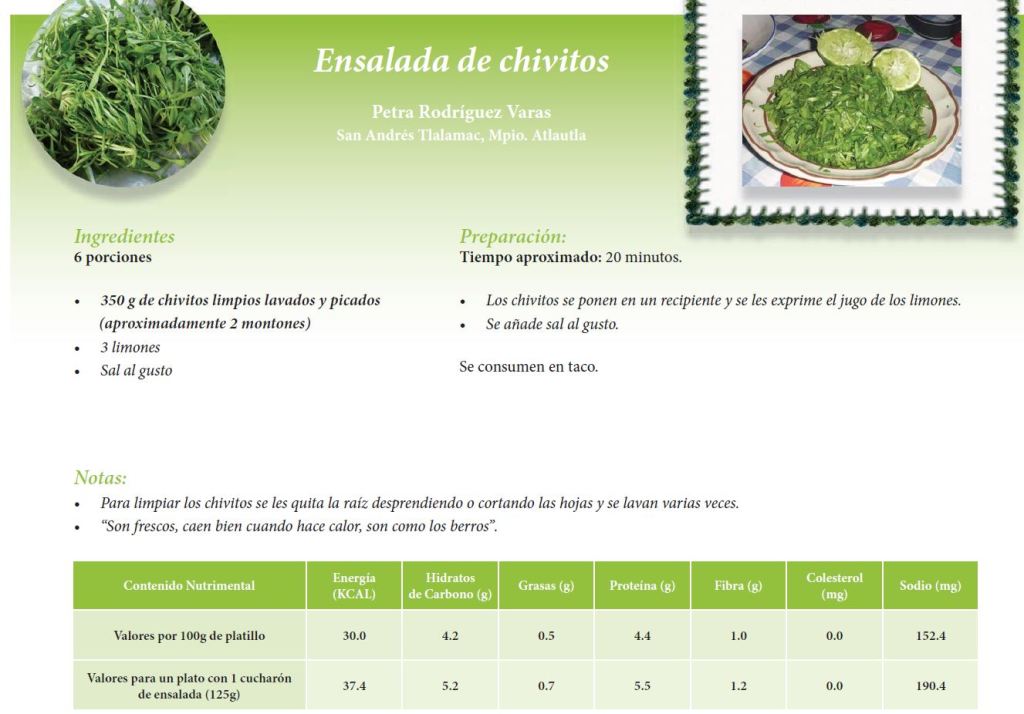

This is a very simple herb to consume. Clean it, add a sprinkle of salt and lime juice, and eat. Use this salad as a filling for tacos and quesadillas.

Other quelites can be added to the mix. Consider using one of the quelites agrios to add a sour tang to your ensalada. Quelite Agrio : Other Sour Quelites. Heed the WARNINGS regarding oxalates though.

Image via Toluca la Bella on FB

Ensalada de quelites chivatos, trébol y queso Oaxaca (Cheese and Quelite Salad)

Ingredients

- Quelites chivatos 500 gr

- Quelites trébol 500 gr

- Queso Oaxaca 200 gr

- Sal al gusto (salt, to tatse)

- El jugo de dos limones (juice of 2 limes)

- Aceite de oliva 1 cucharada (1 Tablespoon olive oil)

Method

- Thoroughly wash the and disinfect the quelites.

- Roughly chop the quelites (only the leaves), mix with cheese, lime juice, salt and oil

- Consume voraciously

The quelites

One WARNING regarding Trebol. This herb is in the family of herbs known as clover. This genus, known as Trifolium, has several drug interactions that will need to be taken into account if consuming this herb in large quantities (or small quantities over a long period – a week or more- of time)

- Oestrogens, hormone replacement therapy, and birth control pills: Red clover may increase the effects of oestrogen.

- Tamoxifen: Red clover may interfere with tamoxifen.Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) medication used to treat breast cancer in men and women and as a prophylactic agent against breast cancer in women.

- Anticoagulants (blood thinners): Red clover may enhance the effect of these drugs, increasing the risk of bleeding.

Trifolium pratense

Back to the cooking

The website La Vitamina T (1) gives a recipe by chef Aldo Saavedra (2) for quelites chivito en pipián. I shall try to translate the recipe here without butchering it too savagely. Chef Saavedra notes that the indigenous name for this dish translates as chilacasmule or tlazompasquéletl.

- https://lavitaminat.com/archives/5807

- This recipe originated with Mrs. Lioba Bonilla Flores, originally from the community of San Andrés, Milpa Alta in Mexico

Chivito en Pipian

Pipián is a green mole made with puréed leaves and herbs and thickened with ground pumpkin seeds. The sauce is said to have origins in the ancient Aztec, Purepecha & Mayan cuisines.

For further information on the culinary art that is mole check out What is Mole? and Quelites y Mole for more ideas on using herbs as the base for this dish.

Ingredients

- ¼ kg sesame seeds

- 15 cloves

- 1 ½ teaspoons cumin

- ½ kg onion

- 8 garlic cloves

- 350g peanut (unsalted, unroasted)

- 1 package of Maria biscuits (4 biscuits)

- 1 (5cm) stick of cinnamon

- 6 guajillo chiles

- 1 kg pork meat (cut into large(ish) chunks)

- 200 gr lard (manteca) (substitute with butter)

- 1 kg chivitos (quelites to taste) – It seems a lot but these will wilt like spinach

Method

- tatemar your onion and garlic cloves (Cooking Technique : Tatemar : “Chef, you realise you’re burning that?”* – just in case you missed it). Set aside

- dry roast each of the spices, chiles, chile seeds, peanuts and sesame seeds separately. Each will have a slightly different cooking time, Roast the seeds and nuts until golden, roast the spices until fragrant and the chiles until slightly darker and fragrant. Be careful not to burn the chiles as they may add bitter flavours to the dish that you don’t want

- submerge the chiles in boiled water until they soften (15 minutes or so). The original recipe called for ALL of the roasted ingredients to be soaked together. I have not seen that in a mole recipe before (but then I am no expert)

- Peel the onions and garlic and place in a blender with the biscuits (cookies for my American brethren), spices and chiles. Blend to a smooth paste. you may need to add a little of the chiles soaking water. You are aiming for a thick paste. This is your mole.

- Simmer the pork in water (maybe flavoured with onion and bay leaf) until cooked. Drain and set aside

- In a pot, add the manteca and heat until it starts to smoke a little and brown the pork.

- Once it is well fried, add the chivitos (or any other type of quelite) and then add the mole. WARNING – if you have health issues that may be affected by the consumption of oxalic acid I recommend simmering the chivitos for 10 minutes in it’s own pot of water (use a non-reactive pan – glass or stainless steel) and then discard the cooking water. If doing this then add the chivitos to the mole/pork mix for the last 5 minutes of its cooking.

- Simmer for 10-15 minutes so the mole thickens and the flavours of the mole, pork and quelites amalgamate.

- Serve accompanied with beans and tortillas.

Mole is a strange dish. Even though it can be loaded with chile (usually more than one variety) it may not necessarily be hot (picante). Moles are often thickened with a carbohydrate such as platanos (plantain – a type of “cooking” banana), tortillas, bread rolls (sometimes brioche) and in this case Maria biscuits. Mole can often be sweet.

Medicinal use

The most common name for this plant after chivatitos/chivitos is lengua de pájaro or “birds tongue”. I only bring this up as there are a few other herbs also known by this moniker and as this plant can be used medicinally it is important that correct identification be made. I speak of this danger in my Post A Note on Deer Weed : The Danger of Common Names.

Other plants identified as Lengua de pájaro

Castillo-Juárez; (etal 2009) notes that the leaves and stems of this plant (1) have traditional use in treating digestive disorders. The paper from the Journal of Ethnopharmacology is an examination of plants used in traditional Mexican medicine and their potential anti-helicobacter activity (2). A methanolic extract showed stronger activity than the aqueous extract did. In this case the tincture is more valuable medicinally than an infusion would be.

- Calandrinia micrantha Schltdl.

- Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a type of bacterium that can live in the lining of the stomach which can cause stomach inflammation (gastritis) and more serious conditions such as stomach ulcers and stomach cancer. Treating and removing H.pylori infection heals most peptic ulcers and reduces the risk of stomach cancer.

Adams (etal 2005) notes that the Chumash people used this herb (C.micrantha) which they called khutash (also xutash), and which is now commonly known as Red Maids (1), as a treatment for arthritis. The Chumash bathed in natural hot springs (whose waters were believed to have medicinal properties) in which they placed various herbs including xutash (2) and bathed themselves “in the water to soothe themselves, comfort their arthritic joints and to feel normal again“.

- also called Fringed Red Maids

- as well as Californian bay leaves, Umbellularia californica (psha’n in Chumash – pronounced pshokn).

References

- Adams, James D.; Garcia, Cecilia (2005). The Advantages of Traditional Chumash Healing. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2(1), 19–23. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh072

- Azurdia, César (2016) Plantas mesoamericanas subutilizadas en la alimentación humana. El caso de Guatemala: una revisión del pasado hacia una solución actual / César Azurdia. – – Guatemala : Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Dirección General de Investigación, Unidad de Publicaciones y Divulgación, 2016. 143 p. : il. ; 27 cm. – – (Documento técnico; No. 11-2016) ISBN 978-9929-620-12-4

- Bye, Jr. Robert A & Linares, Edelmira : ETHNOBOTANICAL NOTES FROM THE VALLEY OF SAN LUIS, COLORADO : Journal of Ethnobiology VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2 Winter 1986 : https://archive.org/stream/mobot31753002401377/mobot31753002401377_djvu.txt

- Israel Castillo-Juárez; Violeta González; Héctor Jaime-Aguilar; Gisela Martínez; Edelmira Linares; Robert Bye; Irma Romero (2009). Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of plants used in Mexican traditional medicine for gastrointestinal disorders. , 122(2), 0–405. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2008.12.021

- Coffey. T. (1993) The History and Folklore of North American Wild Flowers. : Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-2624-6

- Contreras Orozco, Carlos Javier (2018), La cocina tradicional en la cultura otomí, México, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México isbn: 978-607-422-981-3

- Damian Barajas, Adela (2019) Conocimientos Tradicionales Asociados al Maiz de la Comunidad de Urapicho en la Meseta P’urepecha : A Thesis : Universidad Autonoma Chapingo

- Jordán, C.A. and Mejia, C.C., Octavio Castelán-Ortega, Carlos González Esquivel. (2002) Agrodiversity: Learning from farmers across the world : This book presents part of the findings of the international project “People, Land Management, and Environmental Change”, which was initiated in 1992 by the United Nations University. From 1998 to 2002, the project was supported by the Global Environment Facility with the United Nations Environment Programme as implementing agency and the United Nations University as executing agency. The views expressed in this book are entirely those of the respective authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Global Environment Facility, the United Nations Environment Programme, and the United Nations University

- Kunkel. G. (1984) Plants for Human Consumption. Koeltz Scientific Books : ISBN 3874292169

- Linares, E., R. Bye, N. Ortega, A.E. Arce. 2017. Quelites: sabores y saberes del sureste del Estado de México. México, CDMX: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Moerman. D. (1998) Native American Ethnobotany : Timber Press. Oregon. ISBN 0-88192-453-9

- Silvia Padilla Loredo (2015) LA CRISIS ALIMENTARIA Y LA SALUD EN MÉXICO Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México ISBN: 968-5573-42-3

- Rzedowski, GC de and J. Rzedowski, 2001. Phanerogamic flora of the Valley of Mexico. 2nd ed. Institute of Ecology and National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity. Patzcuaro, Michoacan, Mexico.

- Sánchez Ramos, Claudia (2017) Los quelites en la alimentación de Tetlatzinga, Soledad Atzompa, Veracruz, México. Thesis : http://hdl.handle.net/10521/4065

- Standley P.C. & J. A. Steyermark (1946 – 1976) Flora of Guatemala : http://www.archive.org/

- Leticia Vieyra-Odilon; Heike Vibrans (2001). Weeds as crops: The value of maize field weeds in the valley of Toluca, Mexico. , 55(3), 426–443. doi:10.1007/bf02866564

- Viesca-González, Felipe Carlos, Alvarado-Carrillo, Diego de Jesús, & Quintero-Salazar, Baciliza. (2022). The quelites in the city of Toluca, Mexico: their collection, commercialization and consumption. Social studies. Journal of Contemporary Food and Regional Development , 32 (59), e221158. Epub March 6, 2023. https://doi.org/10.24836/es.v32i59.1158

- Yanovsky. E. (July 1936) Food Plants of the N. American Indians. Publication no. 237. U.S. Dept of Agriculture (Calandrinla caulescens)

Websites

- https://bush-tucker.tripod.com/html/textonly.html#Nyurngi

- https://laroussecocina.mx/palabra/chivitos/

- https://laroussecocina.mx/palabra/patitas-de-pajaro/

- https://warndu.com/blogs/first-nations-food-guide/pretty-parakeelya

- http://www.conabio.gob.mx/institucion/proyectos/resultados/RG001_cartel.pdf

Images

- Cover Image : Donna I. Ford (1986) : Flora de Veracruz : FascÍculo 51 (octubre, 1986) : Portulacaceae : ISBN 84-89600-04-X

- Calandrinia seed comparison : http://www.flora.sa.gov.au/efsa/images/figures/Fig125-Calandrinia.jpg

- Calandrinia seed size : By Omar hoftun – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91507518

- Globularia salicina: https://www.riomoros.com/2005/04/globularia-salicina-lengua-de-pajaro.html

- Hot springs map : https://songsofthewilderness.com/2014/01/03/trail-quest-a-string-of-hot-springs-part-1/

- Pipian : https://mexicanfoodmemories.co.uk/2019/02/08/pipian-verde-green-pipian/

- Polygonum aviculare : http://www.conabio.gob.mx/malezasdemexico/polygonaceae/polygonum-aviculare/fichas/ficha.htm

- Rumex acetosella : https://www.naturalista.mx/taxa/53195-Rumex-acetosella

- Teloxys graveolens (Willd.) : Bye & Linares (1986)