A friend recently sent me a message saying she’d found something at a second hand store, she didn’t know what it was, but thought I’d like it as it was from México. It turns out she’d found a molinillo or a hand held kitchen tool used in México for mixing and “frothing” hot chocolate.

The literal translation for molinillo often comes out as “grinder”. This is somewhat related to molino “mill” which is the machine/tool/implement used to grind nixtamalised corn into the paste called masa which is then used to make tortillas and atole (smoother grind) and tamales (rougher grind) as well as innumerable other antojitos.

It did cause me to wonder somewhat as to why this stick used to make chocolate frothy would be called a grinder but then I came across several references to it being used to grind the chocolate whilst mixing it. (1)

- the slender handle is gripped between the palms, which are then rubbed together to rotate the carved knob back and forth. This motion grinds the chocolate discs used for the beverages against the pestle bottom of the drinking vessel

To use your molinillo you place your chocolate in the warming milk (although Mesoamericans would not have used this particular ingredient) and using the base of the molinillo to press down on the chocolate, you use a vigorous hand rubbing motion to spin the molinillo in the milk and grind down the tablet of chocolate. Continue until the chocolate has been dispersed throughout the liquid and a nice bubbly foam has formed.

What was new to me was the mention of the grinding of the chocolate with the base of the molinillo. I was taught to break up the tablet/disc of chocolate, place it in the warming milk, and use the heat and the vigorous mixing to “melt” the chocolate.

Before we go any further I feel it necessary to point out that Mexican chocolate is not like Cadburys. Mexican chocolate is made by grinding together roasted cacao beans with sugar and usually cinnamon (and maybe even almonds). This makes the chocolate seem somewhat unrefined. It is not a smooth bar of choc such as Cadburys would make and it certainly does not eat the same as it is a much harder (more solid) block and you’ll find yourself crunching on sugar crystals as you go.

Chocolate being ground at a mill in Oaxaca.

Now I am presented with an interesting case of cultural appropriation which I would like to share (It was a totally new one for me)

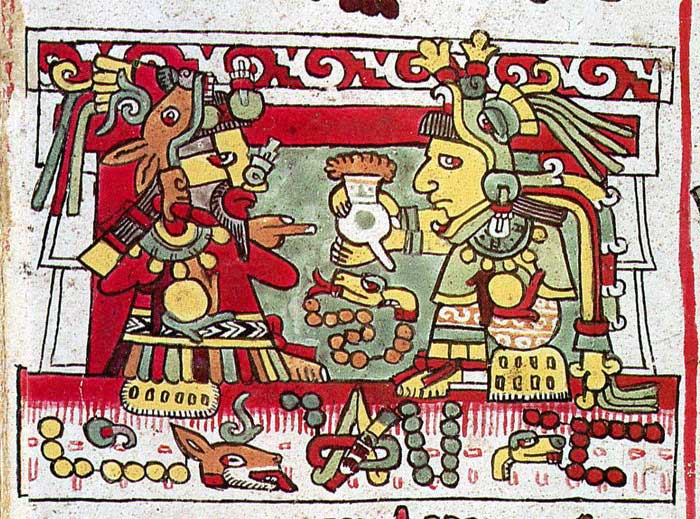

The history of the molinillo is an interesting and somewhat contradictory one. Historically speaking (pre-Columbian that is) it has been noted that the Mesoamericans produced a foam for chocolate by pouring the liquid from a height from one container into another. The image below (right) is from the Tudela Codex and shows an “Aztec woman” pouring chocolate to make it foamy. The image below on the left is from the Zouche-Nuttall Codex and shows the wife of 8 Deer handing her husband a cup of foaming chocolate. This is from the Mixtec people (who occupied sites in Oaxaca and Puebla) and who lived , geographically speaking, within the Aztec empire and quite close to Tenochtitlan.

The Codex Zouche-Nuttall or Codex Tonindeye is an accordion-folded pre-Columbian document of Mixtec pictography produced some time between 1200-1521AD. The Codex is comprised of 47 leaves (or pages) made of painted deer skin and contains two narratives. One side of the document relates the history of important centres in the Mixtec region, while the other, starting at the opposite end, records the genealogy, marriages and political and military feats of the Mixtec ruler, Eight Deer Jaguar-Claw. The Mixtec culture, originally called Ñuu Dzavui (‘the Nation of Rain’), is an important pre-colonial culture of Mesoamerica. The term is made up of Ñuu, ‘people’, ‘country’ or ‘nation’, and Dzavui, which is the name of the God Rain. The Mexica (Aztec) referred to this population as Mixtec (a Nahuatl loan word) which refers to these people as being the ‘inhabitants of the Place of the Clouds’ Very few Mesoamerican pictorial documents have survived destruction (It is one of about 16 manuscripts from Mexico that are entirely pre-Columbian in origin) and it is not clear how the Codex reached Europe. In 1859 it turned up in a Dominican monastery in Florence. Years later, Sir Robert Curzon, 14th Baron Zouche (1810-73), loaned it to The British Museum. His books and manuscripts were inherited by his sister, who donated the Codex to the Museum in 1917. The Codex was first published by Zelia Nuttall in 1902.

The Codex Tudela is a 16th-century pictorial Aztec codex (produced around 1540 – 1553AD) . It is based on the same prototype as the Codex Magliabechiano, the Codex Ixtlilxochitl, and other documents of the Magliabechiano Group. These codices were produced post conquest but are copies of existing pre-conquest codices. The Codex is composed of two documents, the Libro pintado Europeo, of which only 4 pages survive, done in a renaissance style, and the Libro Indigena, which comprises p.11 to 125, painted by native Aztec scribes in a pre-Conquest style and records religious ceremonies, customs, rituals, and festivals of the Aztec of the Valley of Mexico. The Spanish government bought the manuscript after it surfaced in a private home in La Coruña in the 1940s. It is now held by the Museo de América in Madrid. Sr José Tudela de la Orden, after whom it was named, worked at the Museo de America and made the codex known to scholars. In Spanish it is sometimes called the Códice del Museo de América.

Further south, in the lands of the Maya, chocolate (and the foamy type no less) was also very popular.

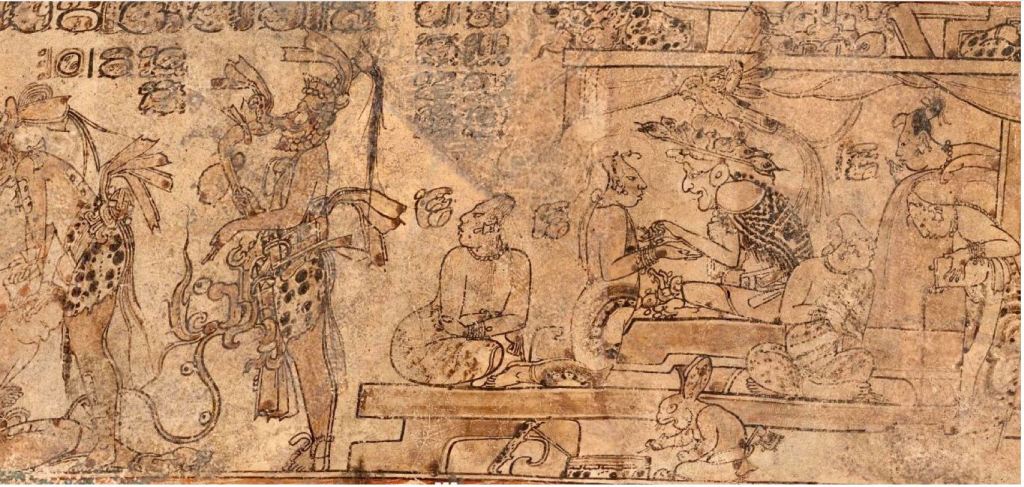

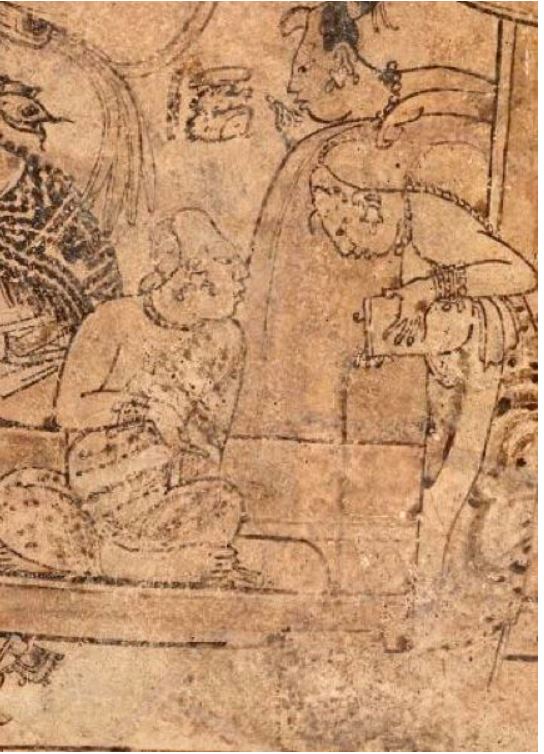

There is a famous Maya chocolate-drinking cup known as the Princeton Vase that shows the process of frothing chocolate by pouring it from a height. This 21.5cm high ceramic cup is decorated with red, cream, and black slip, with remnants of scribe painted stucco and shows the following story (very much like a comic book in my mind)

The Princeton Vase, believed to have been made sometime between A.D. 670–750, belongs to the Late Classic Maya period (600 – 900AD). It has been made in a ‘Codex’ style. Michael Coe (a Mayan researcher) termed the style as he believed the specific and readily identifiable art was produced by the same scribes that had written various Maya codices. There is a definite style to the art. It reminds me of comic books or perhaps tattoos (and would be good source material for both). I wonder if they had popular arts as such and people followed the work of their favourite scribes?

The old, toothless underworld god of tobacco and merchants known as God L, seen at right side of image, sits on a throne within his palace. Two men wearing elaborate masks and wielding axes decapitate a bound and stripped figure, seen at the lower left; the victim’s serpent-umbilicus curls out to bite one of the executioners.

To the right, a standing woman with head bent, holds a vessel (much like the “vase” itself) and a stream of liquid pours down from it, presumably into a vessel whose rendering has eroded. This method of preparation “likely frothed the bitter chocolate beverage that this vessel was made to serve“. Coe considers this method of foam production to be the “exclusive method” of pre-conquest Mesoamerica and that we have the Spanish to thank for the molinillo.

The imagery is quite particular and readily reminds me of my favourite comic book or tattoo artists which is why I query the popular nature of the art. Were these popular collectors items? Were they painted especially for a patron according to a specific request? The imagery does have the feel of a codex.

Click on image to enlarge

The Dresden Codex is one of four hieroglyphic Maya codices that survived the Spanish Inquisition in the New World and is believed to be the writings of the indigenous people of the Yucatán Peninsula in south-eastern Mexico (most probably in the region of Chichen Itza). It is thought to have been written in the 11th or 12th Century AD. The codex in this case was penned a couple of hundred of years after the vase (so it might not be a great comparison)

Now, part of my problem with this is that it has been stated by a (well published) scholar of Mayanism (Coe) that the pouring of the chocolate form one container to another was the “exclusive method” of foam production in pre-conquest Mesoamerica. I have issues with this statement as there are other foamy drinks such as bupu and tejate (both beverages from the Oaxaca region) that have very specialised types of foam (neither of which is produced by pouring) and which demonstrate a highly sophisticated understanding of cacao and its processing.

Coe also bluntly states that Mesoamericans “never” used cacao as an ingredient in foods (such as mole) and that it was only ever drunk and not eaten. Now I do understand that mole (as in mole poblano) was created by the mestizaje, or mixing of cultures, and that it was created by the blending of Mesoamerican and Spanish ingredients and cooking styles but we must also take into consideration that mole might have changed due to the addition of imported ingredients but it was a well established cooking style and dish long before the Spaniards crashed through the door. Saying that Mesoamericans “never” ate chocolate but “only” ever drank it is quite presumptive. Check out What is Mole? for as little more info on both mole and tejate as they relate to the processing of chocolate.

“Foam” comes up a lot, and I suppose it must as it is the very reason for the molinillos existence. For Mesoamerican civilizations, chocolate had ritual significance. In Maya civilization, Gods were connected to cacao trees, often born of them. For the Aztecs, cacao trees were considered the centre of the universe (the axis mundi). As such, chocolate came to have strong religious connotations, and foam was seen as an essential (and sacred) part of the ritual drink. According to ancient tradition, the foam that is created “embodies the spiritual essence of the chocolate” and was seen as the most sacred part of the drink. Yet for the Spaniards and other European countries, these ritual and spiritual aspects were lacking. Chocolate was seen to be a resource in the same manner as gold or spices might be.

Carla D. Martin at Harvard University notes that “Historically, the molinillo has evolved overtime, as one would certainly expect. It was already used for frothing in Mesoamerica and had existed there for quite some time before eventually being adopted by the Europeans” she goes on to say that “Originally made of wood, the molinillo featured a long handle with a ball-like attachment on one end. Traditional molinillos, were quite simple in design and creativeness. Once adopted by the Europeans, they became much more colorful, detailed, and varied in shape and size.” According to Carla “The molinillo represented and still continues to represent a very important a part of that Mesoamerican culture that evolved to our present day society. It wasn’t just used as a simple tool for drink-making; it was a piece of art that had a purpose and meaning to the Mayans and Aztecs.”

By and large though other historians do not concur. It is regularly noted that (although not all sources agree)

An anonymous conquistador travelling with Hernan Cortez described the process of making the drink……“cacao are ground and made into powder, and other small seeds are ground, and this powder is put into certain basins with a point… and then they put water on it and mix it with a spoon. And after having mixed it very well, they change it from one basin to another, so that a foam is raised which they put in a vessel made for the purpose”

Historians note that “At this point, all that is mentioned as a stirring device is a wooden or silver spoon, not the Spanish swizzle stick so often associated with this method of preparation”

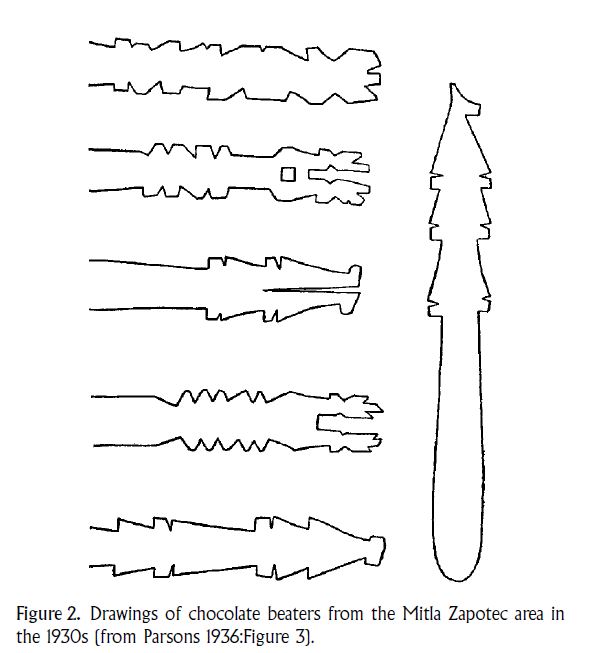

In a paper on the “Uto-Aztecan perspective on cacao and chocolate” (Dakin & Wichmann 2000) it is noted that (a possible) etymology of the word chocolate is derived from the “stirrer sticks” which are used to prepare the drink by “ beating cacao and other spices in hot water with a special instrument to make the liquid foamy”. The work of Parsons (1936) is quoted in the paper and includes a description of these carved wooden sticks. She also mentions that these “[the stirring sticks] are undoubtedly carved more crudely than the Aztec stirring sticks Sahagún reports as beautifully carved”

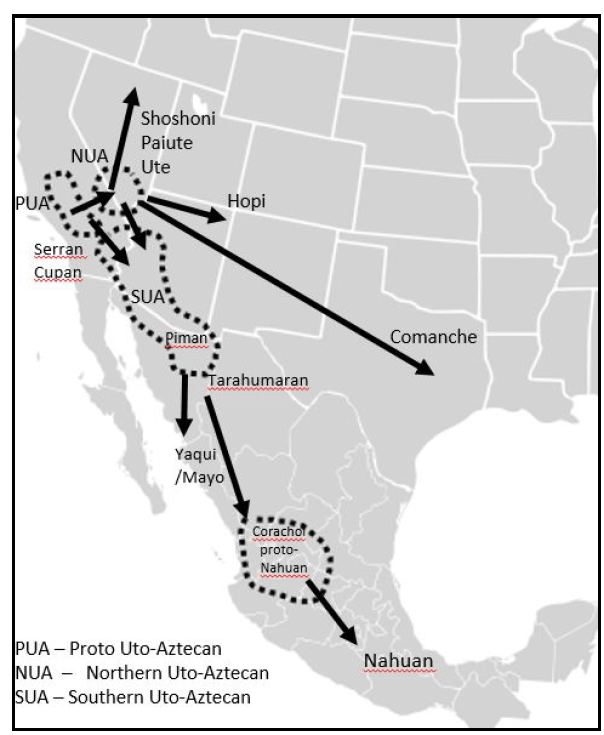

Uto-Aztecan, or Uto-Nahuatl is a family of indigenous languages of the Americas, consisting of over thirty languages and makes up one of the largest and most widespread language families of the Western Hemisphere. Uto-Aztecan languages are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico. The Uto-Aztecan languages are generally recognized by modern linguists as falling into seven branches: Numic, Takic, Hopi, and Tübatulabal, which some scholars consider to make up Northern Uto-Aztecan; and Piman, Taracahitic, Corachol-Aztecan, which some consider to be Southern Uto-Aztecan.

(and isn’t really designed to foam anything)

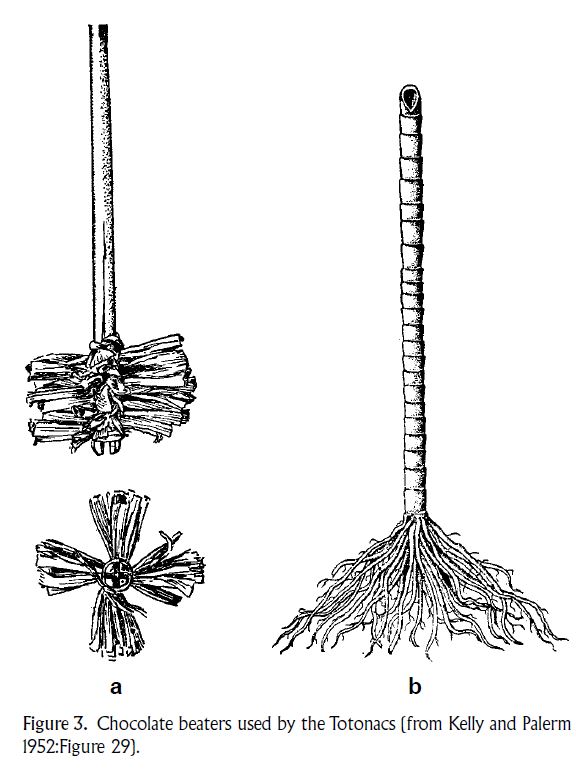

The paper also quotes the work of Kelly and Palerm (1952) who describe two types of “chocolate beaters” used by the Totonacs. One is made from a thin wooden wand into which strips of corn husk are inserted (Figure 3a), another consists of the stalk and (trimmed) roots of the plant tepejilote (Chamaedorea tepejilote).

Although somewhat crude these wooden whisks could be used effectively to mix and foam chocolate drinks

Lets take a look at the etymology of this swizzle stick and see where the history of the word leads up

Barros & Buenrostro (2016) note the Nahuatl names for the molinillo (as recorded by Molina) as being aneloloni, amoloniloni or apozoniloni.

- aneloloni. Principal English Translation: a tool for agitating chocolate beverages : Alonso de Molina, Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, 1571, part 2, Nahuatl to Spanish, f. 6r. col. 1. https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/aneloloni

- amoloniloni. Principal English Translation: a tool for agitating chocolate beverages : Alonso de Molina, Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, 1571, part 2, Nahuatl to Spanish, f. 5r. col. 2. : https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/amoloniloni

- apozoniloni. Principal English Translation: a tool for mixing cacao or chocolate : Orthographic Variants: apoçoniloni : Alonso de Molina, Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, 1571, part 2, Nahuatl to Spanish, f. 6r. col. 1. : https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/apozoniloni

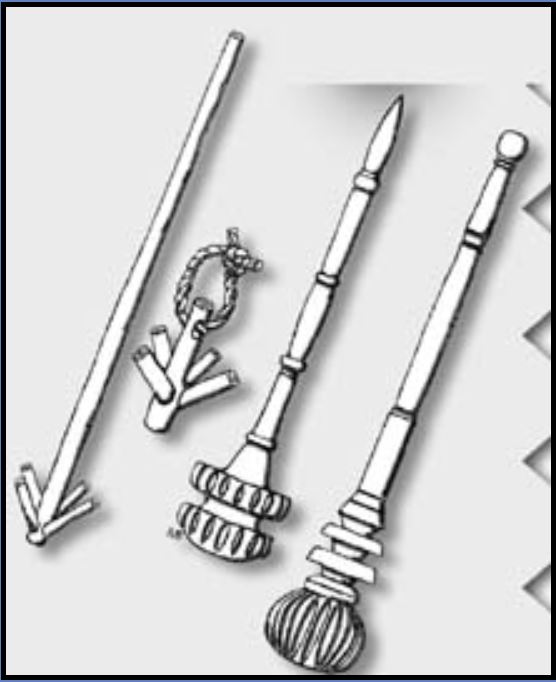

The molinillo is (according to Buenrostro 2002) a relative of the chicoli traditionally used in Chiapas and Tabasco and is considered to be one of the oldest batidores de chocolate (chocolate mixers).

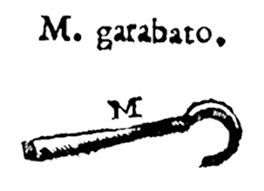

chicolli. Principal English Translation: a hook; a ladle; a long stick; a stirring or frothing stick for chocolate? Orthographic Variants: chiculli Alonso de Molina: chiculli. garauato. Alonso de Molina, Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, 1571, part 2, Nahuatl to Spanish, f. 20v. col. 2. https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/chicolli

Alonso Molina relates the chicoli to an iron instrument, the el garabato de fierro or an “iron doodle”.

el garabato de fierro

Garabato is a hook-shaped instrument used by various craftsmen

• In woollen manufacture , it means a small iron instrument two or three inches long in the shape of a bow, having at each end a point twisted inwards.

• Usually in the kitchens of yesteryear, which obviously did not have refrigerators because they did not yet exist, a hook known as a garabato was hung from a high and cool part, from which sausages and sausages were hung so that they were cool and ventilated.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garabato_(gancho)

Variantes: garabato, garavato.

Definition: Iron instrument with a semicircle-shaped tip, used to hang something, or to grasp or grasp it.

Instrumento de hierro con punta en forma de semicírculo, que sirve para tener colgado algo, o para asirlo o agarrarlo. (DLE).

https://dicter.usal.es/lema/garabato

Buenostro (2002) also notes another name for this tool as being an acuauhuitl. Para tomar la espuma se utilizaba el acuauhuitl que solía ser de madera aunque los había de carey y otros materiales “To take the foam, the acuauhuitl was used, which was usually made of wood, although there were tortoiseshell and other materials”

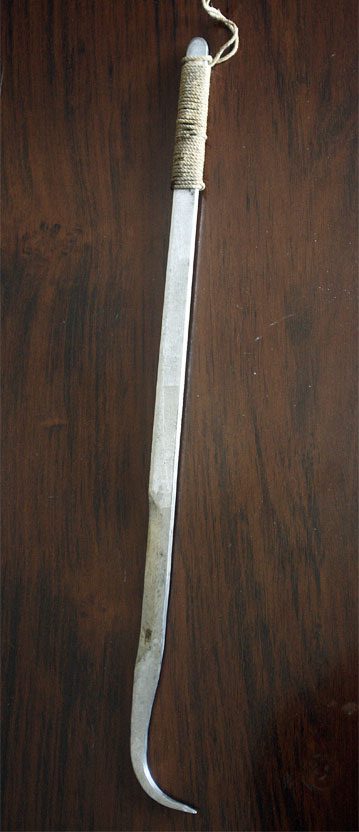

Now I could find no reference material for an acuauhuitl and every search wanted me to be sure I didn’t mean macuahuitl (which I don’t). The macuahuitl is a hand held weapon utilised in steel free Mesoamerica. It is a wooden hafted weapon (think cricket bat) which was edged with knapped obsidian blades. It is a fearsome and deadly weapon of war.

It is now that things get confusing an oddly appropriative.

There is no doubt that the Mesoamericans had expansive and sophisticated knowledge of cacao and its processing. This is evidenced by the Oaxacan drinks such as tejate and bupu (as mentioned earlier) which are completely prehispanic and are created using indigenous ingredients that are not used today (except by those in the communities from which the various flowers/spices originate). We also have tools such as the chicoli which, although quite basic in design, are more than effective at raising a foam. .

Today the molinillo is depicted as a distinctly Mesoamerican or Mexican tool. This mention of it being a Mexican artefact seems to offend some who complain that the Spanish and European involvement in its creation is minimized and sometimes even neglected all together. They want to know “why has contemporary culture diminished the importance of the Spanish and European past of the molinillo and augmented its Mexican one?”

200 years after the conquistadors observation of the making of chocolate the work of an Italian, Francesco Saverio Claviergero, who published a report on native Mexican life describes the use of the molinillo but “totally omits the pouring from one vessel to another to produce a good head on the drink” and that “by 1780, the molinillo supplanted the former foam-making process completely”.

I feel that we also need to take into consideration here that previously chocolate was only a drink of the nobility and the very wealthy (plus some pochteca too probably). The campesino, the common man, you know, us peasants, we could never previously afford chocolate (nor probably even been allowed to consume it) so now, only a couple of generations after the fall of the domination of those friggin Aztecs we can now consume the sacred chocolate. All the Old Gods are laying buried under the cowl of Catholicism, all the old rituals are no longer held, songs are being forgotten, dances no longer danced. The ritual and theatre of pouring foam? Not as relevant. Lets just mix it without all the excess baggage?

Maybe not. Lets get back to the ignorant savages shall we?

When the Spanish arrived in Mesoamerican in the 1500s, they were fascinated with the drink and were determined to simplify the process of creating this delicious beverage, and thus, the molinillo was created.

Instead of having to pour the paste with water from pot to pot, the Spanish invented a small wooden stick with a sphere at the end to stir the paste in one container and avoid separation. This creation, which was started in Mexico, was shared with the Natives of Mesoamerica, and with that idea they created larger, more intricate versions of the molinillo.

Various writers note that….

- the molinillo is a type of wooden whisk introduced by Spanish colonists to froth chocolate

- the molinillo is often incorrectly attributed to being part of the ancient Aztec or Maya process for preparing chocolate

- in the mid-16th century, Creole Spaniards introduced the molinillo in Mesoamerica, an innovation in the field of foaming drinks

- the molinillo quickly became adopted in both Mesoamerica and Europe

- and then of course there is the work of Clavigero which is taken by some to indicate that the Spanish introduction of the tool was readily taken up by those ignorant fools who only knew how to make foam by pouring stuff from one jug to another.

Others are less sure…..

- the molinillo was most likely introduced by the Spanish, possibly during the 16th century.

- It is unclear when exactly Spanish colonists introduced the molinillo. The idea that the molinillo was introduced during the 16th century stems from careful deductive reasoning

So. Who did what first? Has Mexico Colombus’ed (1) Spain?

- Columbusing is a term used to describe the act of appropriating a culture for themselves without recognizing its true origins. The term is named after the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, who was credited with discovering the Americas while it was already inhabited by indigenous people. This term is usually a form of slur aimed at white people.

This is an argument for another place. I am curious about this phenomena, and also that of cultural appropriation, as it applies to both cooking and herbal medicine when these are practised outside of the cultures they were born in. I have investigated this a little in previous Posts

- Authentic Mexican Food?

- “Cultural” Appropriation of Cuisines?

- Celebrity Tequila. Cultural Appropriation? Gentrification?

No time for politics. Lets head back to the kitchen

First, we visit the craftsmen.

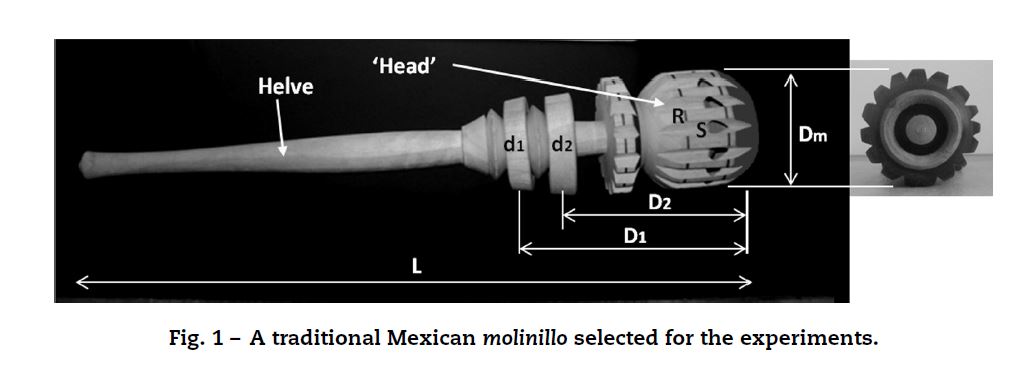

Molinillos are carved from a single piece of wood rotating on a lathe. Typically soft wood from trees like the aile mexicano (Alnus acuminata ssp. glabrata) are used for carving because they are odourless and flavourless and do not impact the flavour of the chocolate when mixing.

The black sections of the molinillo are not painted; rather, the friction from the velocity of the wood spinning on the lathe burns the wood a darker colour, which the crafter then polishes.

Once the base is completed with all the large grooves, all the smaller notch carvings (helpful for circulating the milk to increase frothiness) are completed by hand.

Then they head off to the mercado.

Types of molinillo

Bupu

Bupu is another foamy chocolate drink from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. Its name is derived from the Zapotec bu’pu, which means “foam”. First you make a white atole (atole blanco) and then using a mixture of flowers, spice, sugar and cacao a chocolate foam is made which is then poured atop the atole. The recipe might look something like this….

First make your white atole (1)……

Atole Blanco

- 2 ¼ pounds corn

- Water

Cook the corn in the water. When cooked, you grind it on a metate-stone grinding pad, or in a blender. Strain it and boil it. Serve it very hot with the chocolate mixture on top. (one thing that is not noted here is cal. Corn used to make atole is first nixtamalised with calcium hydroxide (or its ilk) (2). Grinding dried corn and using it to make atole will supply you with a lumpy gruel more similar to grits than atole)

- For a little more info on atole check out Atole de Grano and Quelite : Anís de campo : Tagetes filifolia

- Nixtamal

The chocolate mixure is made from…..

- 9 dried guie’xhuba flowers (a type of night-blooming Jasmine)

- 9 fresh guie’ chachi flowers (a type of plumaria – frangipani).

- 1 ½ pieces of piloncillo (a type of unrefined sugar)

- 6 ounces of cinnamon

- 2 pounds of cocoa.

Toast the cocoa in a comal, and grind it with all the other ingredients, in a metate-a grinding stone. Make a paste. Do this at least one day before you make it.

The next day put a little of the paste and hot water in a huge clay pot with a wide mouth. Whip it until it is really foamy, scoop it out and pour it over the atole.

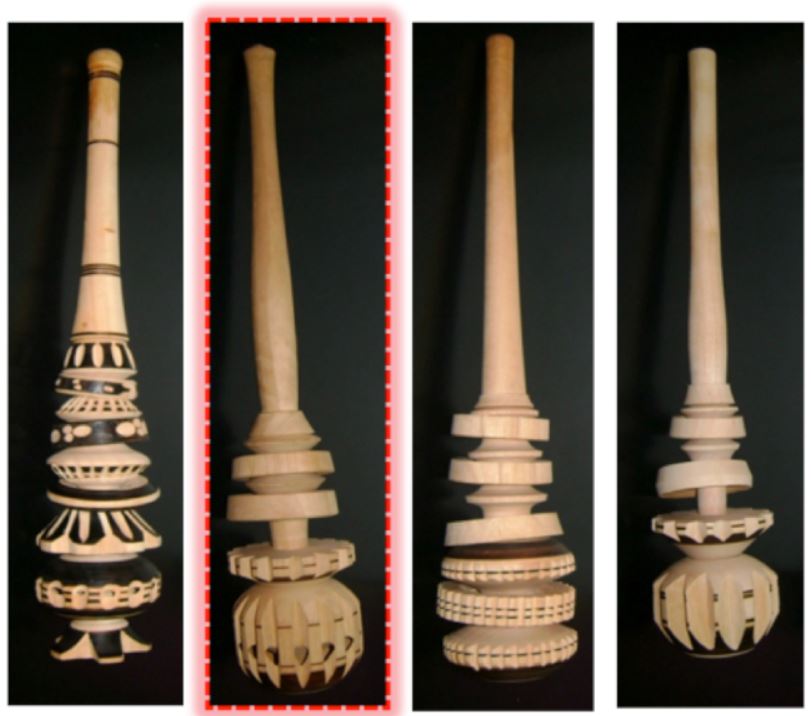

My collection of molinillos.

The very fast forward-backward motion of the molinillo in conjunction with the geometry of the slots and teeth is partially responsible for the mixing performance of this tool. The teeth are important for the introduction of air, for the breakage of bubbles, and for the dissolving of solids, and the slots are fundamental for creating the suction flow required to improve the dispersion of the solids as they breakdown in the liquid being frothed.

The incorporation of a higher amount of air in the chocolate (to produce foam) is mainly defined by the breaking of bubbles. This breakage occurs mainly during the change in the direction of the movement of the molinillo as it is rotated between the palms of the cocinero. The bubbles collide with the structure of the molinillo during this process to counteract the inertia and are thus broken into smaller bubbles. The bubbles that remain in the lower section of the molinillo are capable of being sucked in and colliding with the walls of the teeth, which also causes bubble breakage.

Note the different structural forms of the bottoms of these different molinillos. Initially I had though that some were designed this way simply so that they could be set standing upright on a surface such as your kitchen counter. The idea that this part of the structure is used as a grinding tool to break down the tablet of chocolate by grinding it against the base of the cooking pot makes a lot of sense and it has changed the way I use this tool.

Different varieties of molinillo. Some new, some old, and some antiques.

and now they come in plastic too

Or perhaps something a little more modern?

References

- Barros, Cristina & Buenrostro Marco. (2016) Tlacualero. Alimentación y cultura de los antiguos mexicanos : Primera edición : Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán. ISBN 978-607-7797-23-4 I

- Buenrostro, Véase Marco (2002) “Molinillo” en Tradición y cultura, La Jornada, 23 de enero de 2002.

- Clavigero, Francesco Saverio (1789) Storia della California : https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_spa_4/20/

- Coe, Sophie D., and Michael D. Coe. The True History of Chocolate. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1996.

- Cullen, Charles (translator) The history of Mexico. Collected from Spanish and Mexican historians, from manuscripts and ancient paintings of the Indians. Illustrated by Charts and other copper plates. To which are added, critical dissertations on the land, the animals, and inhabitants of Mexico / By Abbé D. Francesco

- Dakin, Karen, and Søren Wichmann. “CACAO AND CHOCOLATE: A Uto-Aztecan Perspective.” Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 11, no. 1, 2000, pp. 55–75. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26308030. Accessed 9 Oct. 2023.

- Dreiss, Meredith L. and Sharon Edgar Greenhill. Chocolate: Pathway to the Gods. University of Arizona Press, 2008

- Galindo, Enrique; Corkidi, Gabriel; Holguín Salas, Alehlí & López López, Diana. (2014) Producción de espuma en el chocolate con el molinillo tradicional : Revista Digital Universitaria ISSN: 1607 – 6079 | Publicación mensual; May 1, 2014 vol.15, No.5 : https://www.revista.unam.mx/vol.15/num5/art37/

- Green, Judith Strupp. “Feasting with Foam: Ceremonial Drinks of Cacao, Maize, and Pataxte Cacao.” (2010).

- Green, J. S. (2009). Feasting with Foam: Ceremonial Drinks of Cacao, Maize, and Pataxte Cacao. Pre-Columbian Foodways, 315–343. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0471-3_13

- Holguín-Salas, Alehlí; López-López, Diana; Corkidi, Gabriel; Galindo, Enrique (2015). Foam production and hydrodynamic performance of a traditional Mexican molinillo (beater) in the chocolate beverage preparation process. Food and Bioproducts Processing, 93(), 139–147. doi:10.1016/j.fbp.2013.12.007

- Kelly, Isabel, and Angel Palern (1952) The Tajín Totonac. Part 1. History, Subsistence, Shelter and Technology. Publication No. 13. Institute of Social Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

- Martin, Carla. “Chocolate Expansion”. Harvard University, AAAS E-119. Cambridge, MA. Lecture.

- Olver, Lynne. “Food Timeline FAQs: Aztec, Maya, & Inca Foods and Recipes.” The Food Timeline–Aztec, Maya & Inca Foods, http://www.foodtimeline.org/foodmaya.html#aztec.

- Parsons, Elsie Clews (1936) Mitla, Town of the Souls. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Presilla, Maricel E. The new taste of chocolate : a cultural and natural history of cacao with recipes. Berkeley Calif: Ten Speed Press, 2009. Print.

- Soleri, Daniela and Cleveland, David A. , ‘Tejate: Theobroma Cacao and T. bicolor in a Traditional Beverage from Oaxaca, Mexico’, Food and Foodways, 15:1, 107 – 118 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07409710701260131

Images

- Bupu and molinillo : Image by Lon&Queta via flickr : https://www.flickr.com/photos/lonqueta/9155691920/sizes/l/

- Bupu foam : De Debbie Gonzalez Canada – https://d36tnp772eyphs.cloudfront.net/blogs/2/2017/12/Bupu.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Carving the molinillo : still from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CoHCG6hMi2E

- Flor de mayo (Plumeria species – Frangipani) : De Billjones94 – Trabajo propio, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=121647362

- Garabato : https://dicter.usal.es/lema/garabato

- How to Use a Swizzle Stick : https://www.thrillist.com/how-to/how-to-use-a-swizzle-stick

- Macuahuitl : https://www.quora.com/What-are-the-common-weapons-used-by-the-Aztec-military-forces

- Molinillo making : Arte Alonso : https://ciudadolinka.com/2018/05/05/el-molinillo-utensilio-de-la-cocina-mexicana/

- Molino making #2 : De Juanscott – Trabajo propio, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=76977860

- Molinillo or Chocolate Whisk : Smithsonian Record ID: edanmdm:nmah_1460191 : https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1460191

- Molinillo or Chocolate Whisk : Smithsonian Record ID: edanmdm:nmah_1460190 : https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1460190

- Pretzel macuahuitl : https://jasmingimenez.wordpress.com/2017/06/22/mesoamerican-treat-preztel-macuahuitl/

- Wooden whisk (bundle of sticks) : Roede, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons