I have briefly looked at this herb in my Post Papalo and Pipicha. Skunk Weed? and as it is tantalisingly close to my love papalo I would like to investigate it a little more deeply (and grow it if I can source the seed).

Also called : Yerba del Venado, Coronilla, Cempasuchil sencillo, Corona de Rey, arnica, San Felipe dyssodia, San Felipe dogweed, San Felipe Fetid Marigold, San Felipe Marigold, poreleaf dogweed, Cardo santo del norte, Árnica de Cerro, árnica del monte, calendula fetida, flamenquilla, hierba del arriero

Synonyms (1)

- Dyssodia porophylla var.radiata DC

- Pteronia porophylla Cav.

- Adenophyllum porophyllum Hemsl.

- Lebetina porophylla A. Neis

- A Synonym is an alternative name which has been used to refer to a species (or to a subspecies, variety or forma) but which The Plant List does not consider to be the currently Accepted name.

Homotypic (1) Synonyms

- Clomenocoma porophylloides (A.Gray) Rydb.

- Dyssodia porophylloides A.Gray

- Lebetina porophylloides (A.Gray) A.Nelson

- A homotypic synonym is a name that refers to the same type specimen as another name. Homotypic synonyms are based on the exact same type specimen, or holotype. Homotypic synonyms are declared through a ‘nomenclatural act’, that is, published in the scientific literature following the formal rules of the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN). For example, Achnanthes minutissima was transferred to the genus Achnanthidium and renamed Achnanthidium minutissimum. These two names are homotypic, nomenclatural, or objective, synonyms. (Turland etal 2018)

The genus Adenophyllum was published in 1807 by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon.

Adenophyllum (Adenophyl’lum:) is from the Greek word for “gland-leaf” or “having glandular leaves”.

The name dyssodia is from the Greek δυσοδια (dusodia), meaning “bad odour”

The specific epithet, porophylloides (porophyllo’ides:) mean “with leaves like those of Porophyllum”.

Porophyllum is from the Greek “poros”, “a passage or pore,” and phyllon, “leaf,” thus literally “pore-leaf,” because of the translucent glands dotting the leaf which give it a punctate (1) appearance. Papaloquelite : What’s in a name?

- marked with minute spots or depressions

The naming of these plants can be confusing

Adenophyllum porophyllum (Cav.) Hemsl. var. cancellatum (Cass.) Strother ( Villareal, 2001 ) is not synonymous with Adenophyllum porophyllum var. porophyllum or Dyssodia porophyllum var. porophyllum. J. Villareal says: “Apparently the species is strongly related to Adenophyllum porophyllum, differing by presenting heads with ray-shaped flowers, ligules 6-10 mm long, pappus with erous (sic) scales (vs. pappus with ending in hairs) and without having observed intergradation in populations that are in contact”. That is, he considers that they are two different species, not varieties’. Check Regalados (2014) notes a little further down (they only add to the confusion though).

Gioanetto (etal 2010) in the manual of the utilisation of wild weeds (yay quelites) in Michoacan (Manual de utilizaciónde las malezas silvestres de Michoacán) mentions this plant as being of a variety known as malezas silvestres. Maleza – comes from the Latin malitia , malus , meaning “bad.” and silvestres = wild, so the literal translation might be “bad wild” herb or simply “weed”. These plants might also be called mala hierba (1), hierba mala, yuyo, planta arvense (of the field – one assumes the milpa), planta espontánea (spontaneous plant) o planta indeseable (undesirable).

- “mala hierba” is often used to refer to the psychoactive cannabis plant

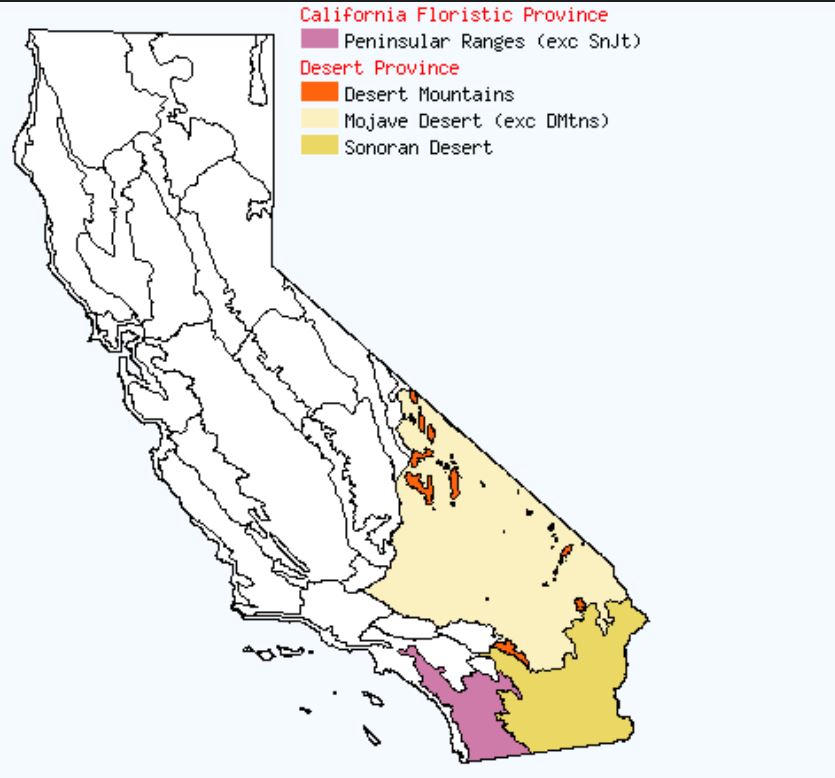

This family of plants is native to the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts of the southwestern United States (Arizona, California, Nevada) and north-western Mexico (Sonora, Baja California, Baja California Sur)

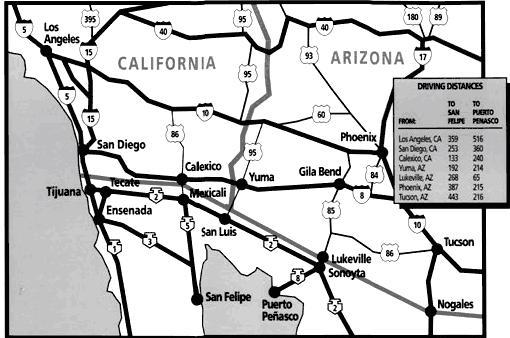

San Felipe is a coastal city in San Felipe Municipality, Baja California, located on the Gulf of California.

This is another example of a strongly scented/flavoured herb common to much of my research.

Kendall (2013) notes that the leaves of this plant “give off a strong odor when bruised”, reportedly similar to that of Deerweed (Porophyllum gracile)”. “Reportedly” is the key word here. It appears that William (much like myself I guess) has no direct experience with this plant and is at this point simply researching.

Others note the herbs scent in a similar manner (and I have no clue if these next few have actually held the plant in their hands). The scent of these plants, along with cilantro and papalo, generally provoke polarising reactions. You either love it or hate it and there may in fact be a genetic reason as to why you might dislike the scent/taste of these herbs….check out my previous Post Cilantro (1). Have your genetics failed you?? (2)

Regarding the powerful odour of this plant (and others) check out the following Posts…….

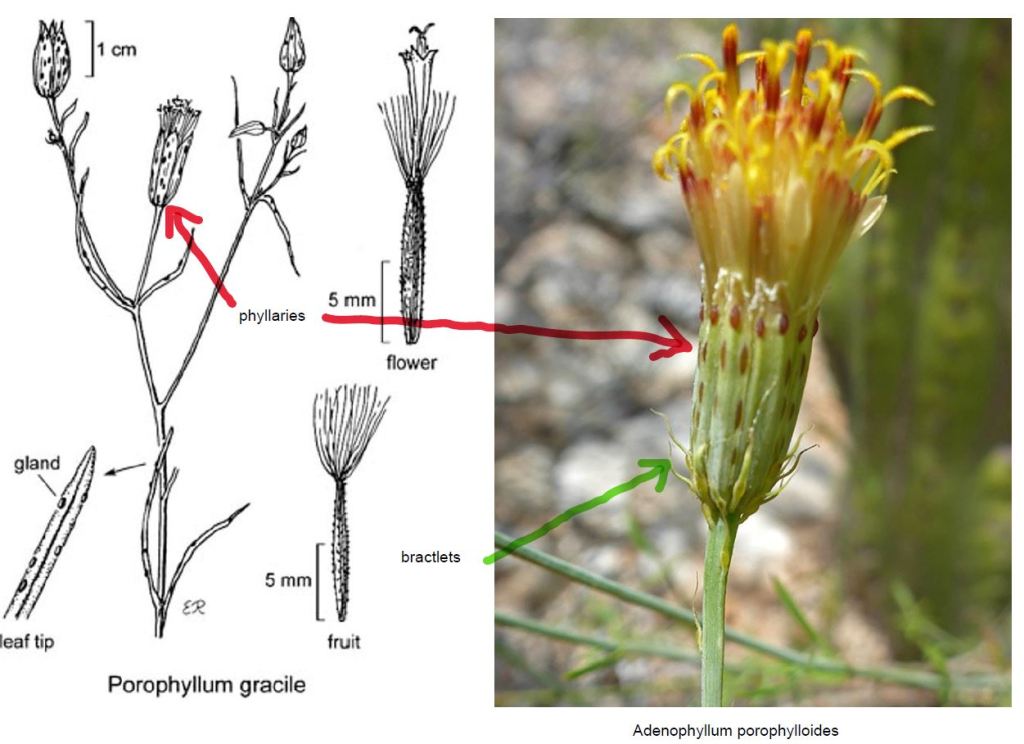

Soutwestdesertflora.com note “At a quick glance San Felipe Dogweed looks superficially like its closely related cousin Odora, Porophyllum gracile, which has significant differences in the flower head. They both also have strong disagreeable odors.”

Fireflyforest.com has this to say of the plant “Special Characteristics : Foul-smelling – The crushed foliage has a strong, unpleasant odor.”

Biological Resources of the Sonoran Desert National Monument (Arizona) has a single line noting “Herbage pungently aromatic.”

Pungent is an odd word. From the point of view of both chef and naturopath this word can mean a number of potentially conflicting things. The word implies an unpleasantly sharp, stinging, or biting quality (especially of odours) and might refer to odours ranging from the smell of a funky cheese (considered unpleasant?) to that of cloves (a dried spice) or even epazote (a fresh herb). As a “taste” quality, various foodstuffs from ginger to mustard have been described as pungent as can the “biting” flavour of radishes or chiles.

From a naturopathic viewpoint pungent herbs are digestive bitters/stimulants and are stimulating, warming, drying and dispersing. They can produce sweating so can be used to help break a fever and improve circulation. They dry and dispel mucus helping to relieve cold, damp conditions and can relieve bloating, gas and nausea.

In Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) pungent flavoured medicinal herbs have the action of dispersing and promoting the circulation of Qi and Blood. They are generally indicated for use in treating exterior syndromes due to invasion of exogenous pathogenic factors and also for syndromes of Qi and Blood stagnation. TCM also applies these same medicinal qualities to various foodstuffs. Associated with metal and autumn, pungent foods are said to benefit the colon and lungs. WARNING : An excess of spicy foods can irritate the intestines. In moderation, they stimulate blood circulation and reduce accumulation in the body. These pungent foods include onions, scallions, radishes, ginger, wasabi (dry mustard), garlic and horseradish.

The folks at the Spadefoot Nursery have some experience with the scent and are a little kinder in their assessment “Not all that long ago, while we were hiking, we came across this plant. We found it in a hill between A Mountain and Tumamoc Hill in Tucson. What was most intriguing about the plant was the odor, which smelled much like the Lemmon Marigold (Tagetes lemmonii). At first I thought we were dealing with a Tagetes species that I didn’t know. Later we figured out that it was San Felipe Dogweed (Adenophyllum porophylloides).” Much kinder. I do grow this herb (T.lemmonii – Mexican Mint Marigold) and if their experiential observation is closer to the mark then this plant is not at all unpleasantly scented.

Now one poreleaf that has come up a couple of times as a comparison to this plant is that of Odora or porophyllum gracile (also called deerweed – Quelite : Porophyllum gracile : Deer Weed). Deerweed is a common moniker for many species within the poreleaf family. For further info on this check out A Note on Deer Weed : The Danger of Common Names).

The foliage of the Adenophyllum has been likened to that of the Porophyllum but I think that aside from the strong scent of the plants leaves there is very little else the two species have in common.

Leaves of the Adenophyllum

Porophyllums are broken down into two main categories, “broad” and “narrow” leaved.

Broad leaved varieties include…..

Narrow leaved varieties include…….

As you can see there is very little (structurally speaking) that the two species have in common

The flowers however are a different case.

The image of the Adenophyllum porophylloides flower above (left) shows the resin glands on the bractlets (1) . These glands are also present on the leaves and phyllaries (2) (as does the P.gracile flowerhead) and they contain the oils said to be responsible for imparting an “unpleasant” odour to the plant (this is highly subjective though).

- In botany, a bract is a modified or specialized leaf, especially one associated with a reproductive structure such as a flower, inflorescence axis or cone scale. Bracts are usually different from foliage leaves.

- In botanical terminology, a phyllary, also known an involucral bract or tegule, is a single bract of the involucre of a composite flower. The involucre is the grouping of bracts together. Phyllaries are reduced leaf-like structures that form one or more whorls immediately below a flower head.

The flowers of A.porophylloides do bear a striking resemblance to those of the Porophyllums, as does the structure of its seeds.

Culinary use.

this plant has been noted as a food stuff in several native American groups. I have seen reference to this not being a good idea due to the presence of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in the plant (which are linked to liver damage). This was a throw away line in someone’s blog (and referred to a paper from the 1930’s but I have yet been unable to find this paper).

Traditionally it was used in this way.

Castetter & Opler (1936) note that amongst the Apache, Chiricahua & Mescalero “The tops of fetid marigold (Dysodia papposa – called tlonda) and shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) are also used as greens, either cooked alone or with meat.” and that “The small seeds of the shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris) and fetid marigold (Dysodia papposa) were secured by cutting off the tops of the plants and beating them on a hide. Then the seeds were winnowed in a basket tray in the wind. After drying they were stored and, when needed, ground into flour for bread. Sometimes the seeds were roasted without grinding and combined with other foods.”

Medicinal use

A.porophylloides

In Kansas the natives breathed the dust of dried leaves (of A.porophylloides) to cure headaches and migraines; The Navajo people used the chewed leaves (as a poultice) to relieve ant bites, while the pioneers used it in tea to relieve stomach pains.

Among the Shonomish Indians (sic) (Gioanetto etal 2010) , the infusion of the leaves was used to wash the hair. In the Sierra Norte of Puebla, the species Dysoddia porophyllum Cav. (hierba del zorillo – skunk weed) is used macerated in alcohol against rheumatic pain, to perform limpias (1) in the case of “mal de aire” and “susto”, while in Saltillo (Coahuila) the infusion of the stem and leaf is used to relieve stomach pain.

- a limpia is a ritual/spiritual cleansing performed in curanderismo. It generally involves a barrida or the “sweeping” of the body with bunches of strongly scented herbs (I have seen basil/albahaca used a lot for this). See my Post Glossary of Terms used in Herbal Medicine. for more information on these procedures.

A curandero performing limpias for the public near the Metropolitan Cathedral just off the Zocalo in México City.

This plant was used in Coahuila and Jalisco as an infusion against stomach pain, while the Totonacos of Veracruz use the branches in baths against mal de aire and chilblains.

Regalado (2014) identifies the plant as Adenophyllum porophyllum (Cav.) Hemsl. var. cancellatum (Cass.) and notes its medicinal use (in Aguascalientes) to relieve stomach pain, especially when something that caused harm has been eaten, the decoction of two or three flowers is taken as a tea.

Many of the uses of this plant revolve around digestive complaints. In the practice of Curanderismo (1) there are specific illnesses that have no real corresponding conditions in allopathic medicine (and is one reason this modality is not taken seriously by modern medical practitioners) and a raft of these conditions fall under the umbrella of “empacho”. Empacho is a core condition (along with susto)(2) that every herbalist (or even bloody doctor for that matter) should learn the curanderistic treatment protocols for as these two conditions alone, if not managed properly, can be responsible for a large number of concurrent illnesses both chronic and acute.

A. porophyllum var. cancellatum

The inhabitants from Tonatico, Estado de México, use the aerial parts of the plant (stems with leaves), with or without flowers, to treat skin affections, such as irritation, infections, wounds, and ulcers. The plant is applied topically to the skin in the form of plasters, poultices, and washes.

The essential oil of A. porophyllum var. cancellatum exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, inhibiting the growth of both yeasts and bacteria. Candida species are the most sensitive to this oil. (Beltrán-Rodríguez etal 2014).

Other medicinal plants in the Dyssodia/Adenophyllum/Thymophylla family

(these names all seem to be synonyms of one another)

Gioanetto (etal 2010) tables the traditional uses of this plant and others in the family.

Thymophylla pentachaeta, also known as fiveneedle pricklyleaf, golden dyssodia or dogweed (syn Dyssodia pentachaeta (D.C) B. L. Robinson) and Dyssodia acerosa have been studied for the medicinal qualities of essential oils extracted from the plant.

In Nuevo Leon, the decoction of Dysoddia setifolia Rob. (parralena) is used as an antidiarrheal.

Ford (1975) notes that in a study of the Hispano-American use of herbs as medicine that amongst a Tewa-speaking Indian group on the Rio Grande in northern New Mexico, the herb parralena (Dyssodia setifolia) was used to treat constipation.

Pichon (1972) notes that “A decoction of Parralena was prescribed by the brujos (in North-Eastern Mexico) as a cure-all for any pain or discomfort of the stomach”.

Kane (2009) goes into more detail on the use of this plant. Under the name parralena (identified as Dyssodia pentachaeta) it is indicated for gastritis (inflammation of the stomach lining), indigestion, gas pains and colic (very much an empacho herb). He says “It serves as a useful carminative, used in relieving gas pains from poorly digested food dependant upon stress or general debility of the area (this is a classic example of empacho illness). A small amount of tea is likewise good for colicky babies. When the stomach lining is inflamed from an overproduction of hydrochloric acid, an excess of alcohol or othe gastric insults, Dogweed tea is soothing”.

The aboveground parts of the herb are harvested when they are at the height of their potency, when they are non-stressed and just prior to or just as flowering begins

Dosage

Leaf infusion 4-8oz (120-240ml = approximately ½ to 1 cup) taken 3 times daily

Try a cup after a meal that has caused bloating and fullness

No Cautions or Drug Interactions known

Analogous (1) uses of an infusion (of others in this family) to treat stomach pain can be found in Nuevo Leon, Zacatecas, and Coahuila with Dyssodia pentachaeta Rob., in Nuevo Leon with Dyssodia micropoides (DC) Loes. (herba del pelotazo) and in Zacatecas with Dyssodia acerosa DC (hierba del burro)

- similar, alike, like, comparable, akin.

Beltrán-Rodríguez (etal 2014) notes that “D.papposa, is a plant that is used as a ceremonial lotion and its seeds ground for consumption. Wyman & Harris (1941) elaborate on this “lotion” as used by the Navajo “

CHANT LOTION

Most ceremonials require a chant lotion which is applied to the patient’s body in ceremonial order, after which he bathes in it and drinks some. The ingredients are mostly members of the Labiatae, although other fragrant plants may be used. Certain plants may be specific for given ceremonials. They may be designated by some combination of the Navajo family name “chant lotion” (keX’o). Chant lotion is used to relieve headache, fever. lameness, and general body aches and pains, and coughs, colds, and chills. Cold infusions are employed. Aside from Dyssodia papposa, herbs used in these lotions include Hedeoma nana, Marrubium vulgare, Mentha spp, Monarda spp., Salvia spp, Aquilegia spp., Thalictrum Fendleri, Whipplea utahemis, Medicago spp., Gaura coccinea., Artemisia spp., Brickellia grandiflora, var. petiolaris, Dyssodia papposa, Eupatorium herbaceum.

The leaves of the plant are used to reduce headaches and fever, it has spasmolytic activity, which is why its frequent use has been reported in the treatment of digestive disorders such as diarrhea, stomach pain and vomiting : in addition to an important antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis and an antifungal effect against Tichophyton mentagrophytes. In the state of Chihuahua, the infusion of the plant is used for the treatment of diabetes.

Under the moniker “Fetid marigold” this plant was used by the Dakota people to treat “cough” in horses, applied to red ant bites by the Navajo, and was used by the Lakota as a treatment for headaches (analgesic), internal bleeding (anti-haemorrhagic), breathing difficulties and as a reproductive aid (Rogers & Dilwyn 1980). The work of these two appears to be an abbreviation of the work of Wyman & Harris (1941) and severely dilutes the wrk of Wyman & Harris (1941). Dyssodia papposa is mentioned in the section “INJURY BY VENOMOUS ANIMALS” and is used as part of a treatment protocol known as the “Red Ant Way”. They (Wyman & Harris 1941) quote the following “Diseases (especially kidney and bladder disease, sudoresis 91), and stomach distress) attributed to swallowing a red ant (in food or water), or to other types of “red ant infection,” may be treated by Red Ant Way; hence plants used for these conditions may pertain to this Chant Way. Decoctions or infusions of the plants are taken internally and are said to “kill the ant.” Itching and sores caused by red ant bites are treated by applying decoctions or infusions as lotions, or by chewing the leaves of the plants and applying them as poultices. The plants may be designated by the Navajo names “red ant medicine”, “red ant killer”, “red ant food”, or included in the Navajo family or form genus “red ant decoction”.

- excessive sweating

Called pispíza tȟawóte by the Lakota peoples of North America, the dried, powdered leaves were inhaled to relieve breathing difficulties and headaches. A decoction made from fetid marigold and Gutierrezia sarothrae (broomweed) is used to treat cough due to colds. A decoction of fetid marigold and Grindelia squarrosa (curlycup gumweed) flowers is used to treat tuberculosis and haemorrhaging

The Omaha reportedly used it to induce nosebleeds to cure headache. (Moerman 2009). Gilmore (1919) notes the plant was also used for its analgesic properties.

Swank (1932) notes the plant was used by the Western Keres people (1) as a febrifuge and smoked for epilepsy.

- The name “Keres” refers to seven present-day Keresan-speaking Pueblo Indian tribes of New Mexico. Acoma and Laguna are commonly designated as Western Keresans. The Cochiti, San Felipe, Santa Ana, Santo Domingo, and Zia peoples are known as the Eastern Keresan.

On the Blog lastrealindians.com D.papposa is noted as being an excellent insect repellent (well mosquitos anyway). Linda TȟióleuŋWíŋ Bishop writes “Dyssodia papposa, also known as fetid marigold, is one of the best insect-repelling plants around. Years ago, I was driven to tears because this pungent weed was invading my garden so badly that almost nothing would thrive. However, I began to notice that I never, and I mean NEVER, got bit by mosquitos at any time of day or night … as long as I was sitting in my garden surrounded by fetid marigold.” She also gives a recipe for a homemade mozzie repellent “Add one cup of fetid marigold to 1 ½ cups of olive oil. Heat on low for two to four hours and then strain. Apply to exposed skin as liberally as desired.”

A. aurantium (L.) Strother is used as an infusion to treat intestinal diseases (amoebiasis). The ethyl acetate root extract has shown to be effective against Entamoeba histolytica (1) trophozoites (Aguilar-Rodríguez etal 2022) and to prevent different steps of the parasite’s pathogenic process, including encystment, liver abscess development, fibronectin adhesion, and erythrophagocytosis

- WARNING : Amoebiasis (a type of “gastro”) is caused by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Most infections are asymptomatic, but may occasionally cause intestinal or extra-intestinal (2) disease. Patients may present months to years after the initial infection. Intestinal disease varies from acute with diarrhoea with fever, chills and bloody or mucoid diarrhoea (amoebic dysentery) to mild abdominal discomfort with diarrhoea containing blood or mucus, alternating with periods of constipation or remission. Fulminant (3) amoebic dysentery is reported to have 55-88% mortality (Dans & Martinez 2007). E. histolytica is estimated to infect about 35-50 million people worldwide (although some estimates state as many as 500 million people are infected with E histolytica worldwide)(Marie 2013). Between 40 000 and 100 000 will die each year, placing this infection second to malaria in mortality caused by protozoan parasites. Seek medical attention immediately if you even suspect that you (or more specifically your child) has this condition. This condition is deadly in children with potentially a nearly 90% fatality rate.

- When the disease affects other parts of the body, this is known as an extraintestinal manifestation (EIM) or complication, patients experience EIMs, commonly in the joints, skin, bones, eyes, kidneys, and liver.

- Fulminant is a medical descriptor for any event or process that occurs suddenly and escalates quickly, and is intense and severe to the point of lethality, i.e., it has an explosive character. The word comes from Latin fulmināre, to strike with lightning.

This is an important medicinal plant

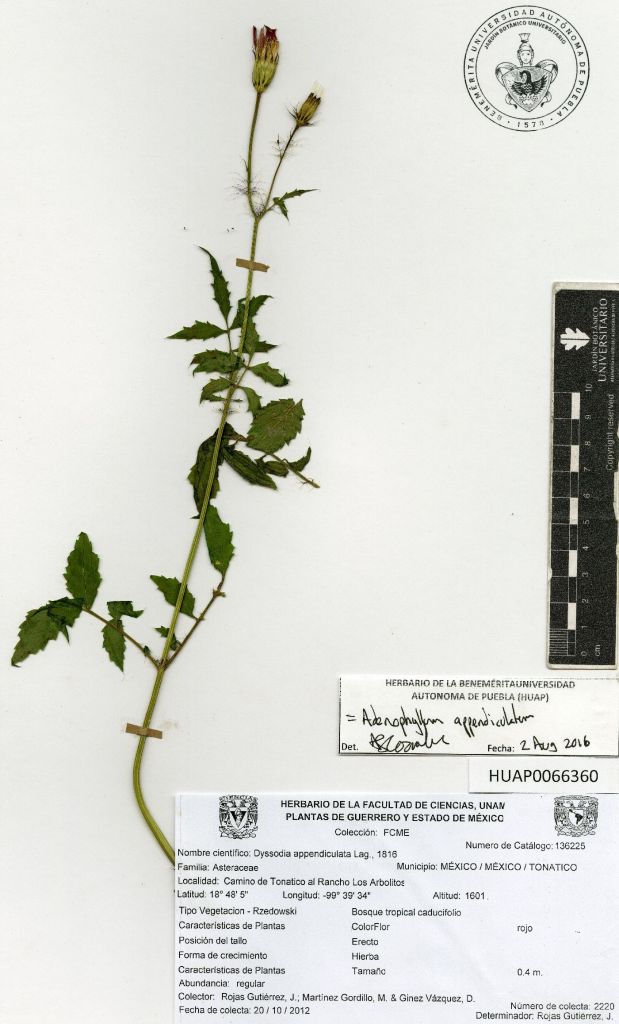

A. appendiculatum (Lag.) Strother (= Dyssodia appendiculata Lag.) is used in Oaxaca, Mexico to treat candidiasis and pain (head, stomach, and gums) and has antibacterial activity (Aguilar-Rodríguez etal 2022)

Cococaquilitl

Adenophyllum glandulosum

Cococaquilitl = Cococ “something that burns the mouth, such as hot peppers (see Molina); misery, tribulation, affliction” and – quilitl (edible herb/vegetable)

Homotypic Synonyms

- Adenophyllum coccineum Pers. in Syn. Pl. 2: 458 (1807)

- Boebera cavanillesii Spreng. in Syst. Veg., ed. 16. 3: 544 (1826)

- Willdenowa glandulosa Cav. in Icon. 1: 61 (1791)

Heterotypic (1) Synonyms

- Adenophyllum capillaceum DC. in Prodr. 5: 638 (1836)

- Adenophyllum cavanillesii Steud. in Nomencl. Bot., ed. 2, 1: 534 (1840), not validly publ.

- Dyssodia cavanillesii Lag. in Gen. Sp. Pl.: 29 (1816)

- Dyssodia coccinea Lag. in Gen. Sp. Pl.: 29 (1816)

- Dyssodia glandulosa O.Hoffm. in H.G.A.Engler & K.A.E.Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. 4(5): 266 (1890)

- Schlechtendalia capillacea DC. in Prodr. 5: 638 (1836)

- Schlechtendalia glandulosa Willd. in Sp. Pl., ed. 4. 3: 2125 (1803)

- A heterotypic synonym is a name that is based on different type specimens. Such synonyms are the opinions of taxonomists rather than formal, nomenclatural rules. For example, Gomphonema louisiananum was first described by Kalinsky (1984). Later, this same diatom was described as Gomphonema patrickii by Kociolek and Stoermer (1995), referring to a different type specimen. These two names are heterotypic synonyms because it is someone’s opinion that these two types refer to different taxa. “Heterotypic synonym” is equivalent to “subjective synonym”.

CAPITULO CXLV : Del COCOCAQUILITL o verdura acuática acre

CHAPTER CXLV : COCOCAQUILITL or pungent aquatic vegetable

Between 1571 and 1576, the protophysician of the King of Spain (Phillip II), Dr. Francisco Hernández visited New Spain at the behest of his liege and wrote his Natural History of New Spain (Historia Natural De Nueva España), a work dedicated to the study of the medicinal plants and animals that were used in these lands.

Hernández describes over 3,000 Mexican plants and includes the term quilitl (which indicates belonging to the group of edible herbs), of which he makes explicit reference to its edible use, as in the case of cococaquilitl or acrid aquatic vegetable, of which he mentions “… the flowers and leaves are fragrant and have an acrid flavor, something similar to the bush, from which he takes name. The indigenous people eat it as a vegetable…”

Acrid, along with pungent (a term I waxed poetic on not that long ago), is an interesting word that really fails to describe the situation as it has a (generally) wholly negative meaning. The Oxford dictionary notes it as being “unpleasantly bitter or pungent” whilst the Merriam-Webster elaborates a little (and harshens the meaning) “sharp and harsh or unpleasantly pungent in taste or odor : IRRITATING” (they, and others, often refer to the smell of burning rubber as a prime example of an acrid odour). This doesn’t exactly do justice to the meaning when we are referring to foods and herbs. Acrid foods are said to include onion, garlic, chiles, ginger, radish (hot and biting maybe, but unpleasant?) and acrid herbs include black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa), kava kava (Piper methysticum), lobelia (Lobelia inflata), blue vervain (Verbena hastata) . You will likely not have tried many (if any at all) of these herbs so from a culinary point of view the flavours here are meaningless (and none of these plants are culinary herbs anyway). Sichuan (Szechuan) pepper is an example of an acrid Chinese culinary spice (it also has medicinal usage).

In TCM Acrid is the flavour of Metal. It disperses and moves accumulations of fluids like Blood, can act as a diaphoretic, and guides qi to the Lungs. Acrid can also be described as pungent or spicy, as it can have a burning or numbing effect (and if you’ve tried Sichuan pepper you know what I’m talking about). Acrid is commonly characterized as both a taste and a smell because of the impact it has on the nose, which happens to be the sense organ of the Metal element. Acridity is utilized to disperse congested mucous in the nose (think wasabi or horseradish)

Hernandez describes cococaquilitl as having “leaves like basil” (las ojas de albahaca) which are “deeply serrated” and “filled with sinuses” which contain an “oil or essence” which has “a strong and unpleasant odor” (un olor fuerte y desagradable). Hernández affirms that it must be a species of Cempoalxochitl, because the smell seems to indicate it, “being characteristic of Cempasúchiles in general; but in this species it is as penetrating as in the Papaloquelite” (1) . He says that “the flowers and leaves are Odoriferous and with a sharp flavor and that in some ways resemble that of mastuerzo” (cress/nasturtium)

- Hernandez’ work on papaloquelite – Medicinal use of Papalo in 1651 as noted by Hernández

Both of the plants noted above are native to the Americas. The Lepidium species (commonly called pepper grass) also has an interesting connection to the naming of Mexico. Check out my Post Quelite : Mexixquilitl for more information on this.

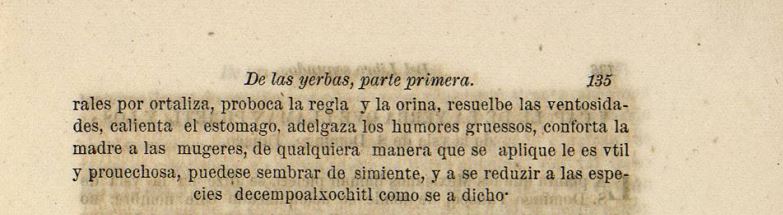

The indigenous people eat it as a vegetable; It provokes urine and menses, eliminates flatulence, warms the stomach, thins the gross humors, strengthens the heart and benefits the uterus in any way it is applied (provoca la orina y las reglas, quita la flatulencia, calienta el estómago, adelgaza los humores crasos, fortalece el corazón y aprovecha al útero de cualquier modo que se aplique)

To cure “mother’s disease” (mal de madre) (1) – cococaquilitl was prepared in the form of a herbal tea to drink

- the discomforts suffered by the women days after giving birth. Rojas (2003) notes that this condituion is more prevalent in women who have given birth in a hospital rather than one at home tended to by a midwife….”Generally, a woman whose birth was attended in the hospital, upon returning home, goes to the “doctor” and midwife to implement the “care” specific to the circumstance in which she finds herself. The so-called “Mother’s Disease” is quite common, because, as several midwives have told me, “the cold in the hospital is very harsh and they don’t give those poor women a single drink, not even a little bit of anything,” and then “the Mother fills with air and ice, becomes weak, and spreads throughout her body.” (Generalmente, una mujer cuyo parto fue atendido en el hospital, al regresar a su casa acude a la “médica” y comadrona para poner en práctica los “cuidos” propios de la circunstancia en la cual se encuentra. Es bastante frecuente el llamado “mal de Madre”, pues, como me han dicho varias parteras, “el frío del hospital es muy bravo y a esas pobres mujeres no les dan ni una tomita, ni una sobita de nada”, y entonces “la Madre se llena de aire y de hielo, se pone débil, y se riega por todo el cuerpo”). I have also seen this term used to denote abortion. My study of this herb however has not once bought up the fact that it was (or could be) used as an abortifacient.

Reprints of “extracts” of Hernandez’s work.

La que llaman cococaquilitl, es una yerba que produze las ojas de albahaca, pero asseradas mas profundamente, y como llenas de senos, pintadas con unas pintillas amarillas tiene cada una tres tallos cada uno de seys esquinas, las flores com dela betonica, o de cempoalxochitl silvestre, cuyas ojas son de color de grana, las quales flores produzen de ciertos vasillos esquarosos, no de semejantes a las del ciamo, las rayzes son como hebras, y suelen tener la planta tres codos de largo, las flores y las ojas son odoriferas y de sabor agudo y que en cierta manera se parecen al del mastuerzo, comenla los natu- (next page) -rale (naturales) por hortaliza, provoca la regla y la orina, resuelbe las ventosidades, caliente el estomago, adelgaza los humores gruessos, conforta la madre a las mugeres, de qualquiera manera que se aplique le es vitl y prouechosa

The one they call cococaquilitl, is a herb that produces the leaves of basil, but more deeply asserted, and as if full of sinuses, painted with little yellow spots, each one has three stems, each with six corners, the flowers like betonica, or wild cempoalxochitl, whose leaves are scarlet in color, the flowers produced from certain squarish vessels, not similar to those of the cyamo, the roots are like strands, and the plant is usually three cubits long, the flowers and leaves are Odoriferous and with a sharp flavor and that in some ways resemble that of the butterflies, they are eaten by natu- (next page) -rale (natural) for vegetables, causes menstruation and urine, resolves wind, warms the stomach, thins the thick humors, comforts the mother (the womb of?) to women, in any way it is applied it is vital and beneficial, it can be sown seed, and will be reduced to the species of cempoalxochitl as mentioned above.

References

- Aguilar-Rodríguez S, López-Villafranco ME, Jácquez-Ríos MP, Hernández-Delgado CT, Mata-Pimentel MF, Estrella-Parra EA, Espinosa-González AM, Nolasco-Ontiveros E, Avila-Acevedo JG and García-Bores AM (2022) Chemical profile, antimicrobial activity, and leaf anatomy of Adenophyllum porophyllum var. cancellatum. Front. Pharmacol. 13:981959. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.981959

- Beltrán-Rodríguez L, Ortiz-Sánchez A, Mariano NA, Maldonado-Almanza B, Reyes-García V. Factors affecting ethnobotanical knowledge in a mestizo community of the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014 Jan 27;10:14. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-14. PMID: 24467777; PMCID: PMC3933039.

- Black Elk, Linda S. (1998) Culturally Important Plants of the Lakota :

- Castetter, Edward F.; Opler, M. E. (1936). “The Ethnobiology of the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache”. University of New Mexico Bulletin. 4 (5): 1–63. Retrieved 04 January 2024

- Dans LF, Martínez EG. Amoebic dysentery. BMJ Clin Evid. 2007 Jan 1;2007:0918. PMID: 19454043; PMCID: PMC2943803.

- Delia Castro Lara, Francisco Basurto Peña, Luz María Mera Ovando, Robert Arthur Bye Boettler (2011) Los quelites, tradición milenaria en México : Universidad Autónoma Chapingo : ISBN 6071202027, 9786071202024

- Estrada-Castillón, E., Garza-López, M., Villarreal-Quintanilla, J.Á. et al. Ethnobotany in Rayones, Nuevo León, México. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 10, 62 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-62

- FORD, KAREN COWAN. Las Yerbas de La Gente: A Study of Hispano-American Medicinal Plants. University of Michigan Press, 1975. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11394874.

- Gilmore, Melvin R., 1919, Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region, SI-BAE Annual Report #33, pages 132133

- Gioanetto, F., Díaz-Vilchis,J. T. and Quintero- SánchezR. (2010) Manual de utilizaciónde las malezas silvestres de Michoacán. Grafópolis. Morelia Michoacán, México.

- Hernández Francisco. 1959. Historia Natural De Nueva España. 1. ed. México: Universidad Nacional de México.

- Hind, D.J.N. Porophyllum woodii (Compositae: Heliantheae: Pectidinae), a new species from Prov. Burnet O’Connor, Departamento de Tarija, Bolivia. Kew Bull 75, 61 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-020-09915-2

- Kane, Charles W. (2009) Herbal Medicine of the American Southwest: The Definitive Guide : Lincoln Town Press : ISBN 10: 0977133311 ISBN 13: 9780977133314

- Kendall, William T, a SPECIES DISTRIBUTION LISTING for TOWNSHIP 14 SOUTH, RANGE 13 EAST PIMA COUNTY, ARIZONA Gila and Salt River Baseline and Meridian : United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, General Technical Report RM-73 : May 8, 2013 Update

- Marie C, Petri WA Jr. Amoebic dysentery. BMJ Clin Evid. 2013 Aug 30;2013:0918. PMID: 23991750; PMCID: PMC3758071.

- Moerman, Daniel E. (2009). Native American Medicinal Plants. Timber Press Inc. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-88192-987-4.

- Angélica Morales Sarabia (2016) La enfermedades de las mujeres en la Nueva España, una taxonomía a través de las plantas emenagogas (siglo XVII) https://doi.org/10.4000/nuevomundo.69565

- Pichon, Wayne M., “Ethnobotanical Studies on Selected Plants of Northeastern Mexico” (1972). Masters Theses. 3857. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3857

- Regalado, Gerardo García (2015) Plantas medicinales de Aguascalientes : Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes : Segunda edición 2015 (versión electrónica) : ISBN 978-607-8359-83-7

- ROJAS, Belkis. Cuerpo y enfermedad en Mucuchíes In: Caminos cruzados: Ensayos en antropología social, etnoecología y etnoeducación [online]. Marseille: IRD Éditions, 2003 (generated 08 janvier 2024). Available on the Internet: http://books.openedition.org/irdeditions/18968. ISBN: 9782709925464. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.irdeditions.18968.

- Swank, George R., 1932, The Ethnobotany of the Acoma and Laguna Indians, University of New Mexico, M.A. Thesis, pages 33

- Turland, N.J., Wiersema, J.H., Barrie, F.R., Greuter, W., Hawksworth, D.L., Herendeen, P.S., Knapp, S., Kusber, W.-H., Li, D.-Z., Marhold, K., May, T.W., McNeill, J., Monro, A.M., Prado, J., Price, M.J. and Smith, G.F. (2018) International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) Regnum Vegetabile 159. Glashütten: Koeltz Botanical Books.

- Urbina, M. (1903). Edible plants of ancient Mexicans. Annals of the National Institute of Anthropology and History , 2 (1), 503–591.

- Vestal, Paul A., 1952, The Ethnobotany of the Ramah Navaho, Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology 40(4):1-94,

- Villareal Q., JA, 2001. New nomenclatural combinations for Mexican compounds. Acta Botánica Mexicana 56: 9-11.

- Villareal Q., JA, 2003. Family Compositae – Tribe Tageteae. In: Rzedowski, GC de and J. Rzedowski (eds.). Flora of the Bajío and Adjacent Regions. Fascicle 113. Institute of Ecology-Regional Center of Bajío. National Council of Science and Technology and National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity. Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, Mexico.

- Wyman, Leland C. & Harris, Stuart K. (1941) NAVAJO INDIAN MEDICAL ETHNOBOTANY : The University of New Mexico Bulletin : Whole Number 366 June 1, 1941 : Anthropological Series, Volume 3, No. 5 : UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO PRESS

Images

Pic2 – Max Licher via https://swbiodiversity.org/seinet/taxa/index.php?taxon=531&clid=8

Pic3 – https://cabezaprieta.org/plant_page.php?id=1194

Pic4 – https://www.birdandhike.com/Veg/Species/Shrubs/Adenop_por/_Ade_por.htm

Pic5 – https://www.birdandhike.com/Veg/Species/Shrubs/Adenop_por/_Ade_por.htm

Pic7 – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Felipe,_Baja_California

Pic8 – https://www.americansouthwest.net/plants/wildflowers/adenophyllum-porophylloides.html

Pic9 – Quelite : Porophyllum gracile : Deer Weed

Pic10 – Papalo and Pipicha. Skunk Weed?

Pic11 – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Porophyllum_gracile_-_Flickr_-_aspidoscelis_(3).jpg

Pic12 – By Stan Shebs, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4758882

Pic13 – https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/eflora_display.php?tid=724

Pic14 – https://www.birdandhike.com/Veg/Species/Shrubs/Poroph_gra/_Por_gra.htm

Pic15 – https://calphotos.berkeley.edu/cgi/img_query?enlarge=0000+0000+0312+2539

Pic16 – https://serv.biokic.asu.edu/imglib/h_seinet/seinet/ASU/ASU0013/ASU0013986a_lg.jpg

Pic17 – https://cabezaprieta.org/plant_page.php?id=1466

Pic18 – https://swbiodiversity.org/imglib/h_seinet/seinet/Asteraceae/photos/Thymophylla_acerosa_020207_2.jpg

Pic19 – https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:286094-2/images

Pic20 – https://www.wildflower.org/gallery/result.php?id_image=49763

Pic21 – http://www.conabio.gob.mx/malezasdemexico/asteraceae/thymophylla-setifolia/imagenes/cabezuelas.jpg

Pic23 – https://inaturalist-open-data.s3.amazonaws.com/photos/13645307/original.jpeg

Pic24 – https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/9269653

Pic25 – https://swbiodiversity.org/imglib/seinet/swnode/HUAP/00066/66360.jpg

Pic27 – Castetter, Edward F.; Opler, M. E. (1936). “The Ethnobiology of the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache”. University of New Mexico Bulletin. 4 (5): 1–63. Retrieved 04 January 2024

Pic28 – https://uk.inaturalist.org/observations/141755714

Pic29 – https://uk.inaturalist.org/observations/187261921

Pic30 – https://uk.inaturalist.org/observations/8523329

Pic31 – https://uk.inaturalist.org/observations/187261921

Pic33 – http://cdigital.dgb.uanl.mx/la/1080019528/1080019528_24.pdf

Pic34 – http://cdigital.dgb.uanl.mx/la/1080019528/1080019528_24.pdf