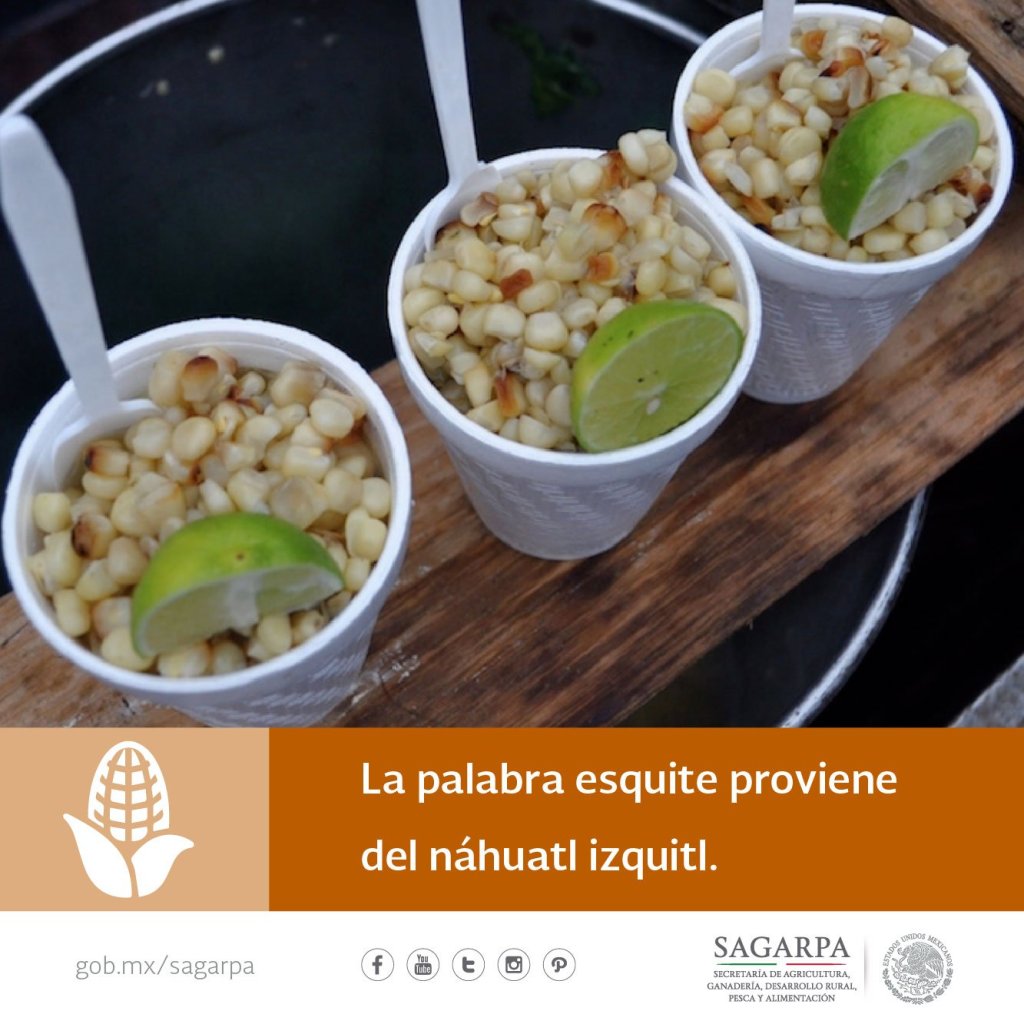

Esquites are a “ Mexican snack ” composed mainly of seasoned, boiled corn kernels served in a cup. They are a well known and loved snack throughout all of México. Vendors can be found on street corners, bus stations, train stations and in mercados pumping out the most fundamental (and probably the most original) street food of all Mesoamerica.

Now do you want it on the cob or no? It makes a difference

On the cob = elotes

In the cup = esquites

But is it really that simple? I mean corn in a cup is corn in a cup si?

Well…..not really.

Every cuisine has its regional variations and even a recipe as simple as corn on the cob (or in a cup…..to your preference por supuesto) and in Mexico there is of course the obligatory North/South rivalry.

The word esquite, as previously noted, is of Nahuatl origin, regardless of the logic of angry cowboys.

According to the Government of Mexico website, the name Esquites comes from the Nahuatl “ízquitl”, which can be translated as “maíz tostado” or “tostado” (“toasted corn” or “toasted”). It is said that they were created by Tlazocihuapilli, “the only woman who ruled the Xochimilcas and who gave life to dishes such as necuatolli, capultamalli, tonalchilli, atole with honey, and tlapiques (1). Tlazocihuapilli is also said to have created the first tamale leaf wrappers (2).

- Vitamina T : The Tlapique. Cousin of the Tamal.

- it has also been said she invented a dish made with vermin from the canals and lakes, adding wild quelites from the chinampas. This dish is called Mixmole or Michmole Michmulli which means fish stew, which is currently prepared with chard, axolotl and fish, as well as acociles and frogs. Check out Quelites y Mole for a recipe containing wild quelites (adding vermin is entirely up to you) and if you need a little revision on the Mexican dish called mole then check out What is Mole?. For some recipes from the canal inhabiting Xochimilca that likely originate from the days of Tlazocihualpilli (and that do contain vermin) check out Vitamina T : The Tlapique. Cousin of the Tamal..

izquitl.

Principal English Translation: popcorn; also used to describe many plants and trees that produce clusters of white flowers (see Karttunen)

Orthographic Variants: īzquitl

Frances Karttunen: ĪZQUI-TL popcorn (used to describe many plants and trees that produce clusters of white flowers) / maiz tostado; flor muy olorosa (S) [(1)Tp.170,(3)Xp.40]. M has izquiatl ‘drink made of ground popcorn.’

Bouerreria huanita is one such tree (as mentioned above)

The fragrant white flowers of Bouerreria huanita are called teoyzquixochitl (sacred izquitl flower) and are known to have been used in the pre-Columbian period by the Mexica of highland Mexico in medicine, in sacred gardens, as a flavouring in cacao beverages (McNeil 2012), and as floral garlands to adorn individuals for “sacred rites” (Mathiowetz etal 2021).

Duran (1967) notes izquiatl as a type of fasting food called “agua de esquites” that was made and consumed (for a period of five days) by the widows of warriors who fell in the Chālco war. Chālco was an altepetl (independant city-state) who paid more tribute to Tenochtitlan (in the form of food) than any other region in the Valley of Mexico, probably because of its fertile soil and location (Schroeder 1991). In 1446 they refused to pay tribute to the Mexica who demanded building materials for their new temple to Huitzilopochtli. The Azteca attacked them in earnest and by 1465 the nation had been completely defeated and their rulers exiled. After 1519 the remaining Chalca allied with the Spaniards (and other Mesoamerican “tribes”) and participated in the defeat of the Mexica.

Tlazocihuapilli is an interesting figure.

tlazo-.

Principal English Translation: dear, precious (see attestations)

Orthographic Variants: tlaço-, tlazoh-

Attestations from sources in English: tlazotli = precious one; tlazotlacatl = precious lord; tlazopilli = precious prince (central Mexico, sixteenth century)

cihuapilli.

Principal English Translation: noblewoman, lady

Orthographic Variants: civapili, tzinhuapilli, civapilli, ciuapili, ciuapilli, suapili, cioapilli, zoapilli, zouapilli

Alonso de Molina: ciuapilli. señora, o dueña.

Daneels & Gutiérrez Mendoza (2012) mention tlazocihualpilli as an honorific term in regards to intermarriage between members of opposing (and of a lower “class”) alpeme (1). If the tlatoani of a “type 1” altepetl married a woman from a “type 2” (lower classed) altepetl then any sons from the union could never be tlatoani of either altepetl. However that childs children (the grandchildren of the original tlatoani who “married down”) could marry a tlazocihualpilli (“precious noblewoman”) from the grandmothers altepetl (the one of lower hierarchy) and could aspire to, and even reach the dizzying level of power as tlatoani of that altepetl.

- alpeme is a plural of atlepetl (city state)

Wikipedia notes of Tlazocihualpilli “Xochimilco had one woman ruler, which did not happen anywhere else in Mesoamerica in the pre-Hispanic period.” The reference used to support this claim however opens to a “404 File not found” error notice and I’m currently having trouble accessing the data as every other reference to this person quotes the Wiki almost word for word and none supply the appropriate reference material.

It took some doing but a little more info has come to light.

In the Congress of Mexico City (Congreso de la Ciudad de Mexico – 2nd Ordinary session of the 1st year of exercise Feb 21 2019) it was noted that “Xochimilco has a long tradition of women’s participation in social political life, In pre-Columbian times, for example, there are references to Tlazocihualpilli, who was the first female ruler of the Xochimilca People and practically the only reference of the gender city in decision-making prior to conquest.” Colaboración (2021) notes her reign to have occurred between 1335 and 1347. Acevedo López & de la Cruz (2007) expand on this….and note that in the “Anales de Culhuacan” in the year 12 Acatl (12 Reed – 1335) Cuauhtiquetzal, the Tlatoani of Xochimilco dies and Tlazocihualpilli is enthroned and that she is the only known female Xochimilca ruler. In the year 11 Acatl (11 Reed – 1347) Tlazocihuapilli “leaves power” after 12 years on the throne and Caxtotzin is enthroned as tlatoani of Xochimilco.

Esquites

This is a base recipe (using fresh, yellow – even sweet – corn). This recipe (if you removed the garlic and butter) is pretty much how a prehispanic chef would have prepared this dish.

Ingredients

- Kernels shucked from 6 fresh ears of maize (granos de 6 elotes)

- 2 cloves garlic (minced)

- 5 chopped epazote leaves

- 2 green chilies (chiles verdes – serrano or jalapeno often recommended)

- 30 grams of butter

- salt to taste

Method

- In a frying pan, melt the butter and sauté the garlic; then, add the chiles and epazote.

- Add the corn kernels, mix all the ingredients and add salt to taste.

- Cook over medium heat and stir constantly, so that the kernels do not stick to the pan.

- When the grains are soft and transparent in color, the esquites are ready.

This next recipe mestizajes (not the way the term is supposed to be used) on the previous one a little with foreign additions such as olive oil, mayonnaise, cilantro and cumin.

Mexican Street Corn Salad: This recipe was sourced from the el Restaurante (Mexicano) Magazine, an industry publication for Latino restaurants.

- 1 T. olive oil

- 3 ears of fresh corn, shucked, kernels removed

- ½ c. scallions, thinly sliced (in Straya we’d call these “spring onions”)

- ½ c. cilantro, chopped

- 1 large jalapeño, finely diced

- ¼ c. mayonnaise

- 1 lime, juiced

- ½ t. cumin

- ½ t. chili powder

- 2 cloves garlic, pressed or finely minced

- Salt

Add the oil to a large sauté pan over medium-high heat. Add the corn kernels to the hot pan and season with salt. Allow the corn to char and heat through, stirring occasionally, about 4 minutes. Remove from heat and set aside.

In a mixing bowl, add the scallions, cilantro, and jalapeño. In a smaller bowl, whisk together the mayonnaise, lime juice, cumin, chili powder, and garlic until smooth. Add the corn to the mixing bowl with the scallions, cilantro, and jalapeño. Pour the mayonnaise lime mixture over top and fold everything together to combine. Season with more salt as needed to taste.

This next recipe is from Morelos and is a further expansion on the two previous recipes and I include it here as it contains a herb pericón or yerbanis (Tagetes lucida) which is native to the Americas. This herb is often used when cooking elotes and has (as its name suggests) an anis flavour. Pericón is often called Mexican tarragon so If you know the French herb tarragon you will understand the flavour profile of pericón. Visit Quelite : Pericón : Tagetes lucida to investigate this herb further.

Morelos style esquites

Ingredients :

- ½ kg corn kernels

- 1 tbsp butter

- ½ white onion, finely chopped

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 zucchini, cut into half moons

- 1 cup squash/pumpkin flower, cleaned

- 4 cups of water

- 1 sprig **NOTES** of epazote

- 1 sprig of pericón (yerbanis)

To accompany:

- 1 limón, quartered

- 1 manzano chile, finely chopped

Procedure :

- in a hot saucepan, melt butter, add onion and garlic. Add corn and fry for a few minutes. Then add zucchini, pumpkin flower and fry for a few more minutes.

- Add water, epazote, pericón flower and cook until the corn is cooked. Adjust seasoning.

- To assemble , serve esquites in small glasses, accompany with lemon and manzano chili.

**NOTES** a sprig is a small shoot or twig of a herb, especially with leaves or flowers.

The following two recipes differ in that instead of yellow sweet corn they use white corn (cacahuazintle) that may not be readily available (in Australia at least anyway).

Cacahuazintle

Esquites Mexicanos (My Latina Table)

Ingredients

- 6 Cups white corn kernels (granos de elote blanco)

- 1/2 white onion finely chopped (or 2 tablespoons onion powder)

- 3 large cloves of garlic, finely chopped (or 2 tablespoons of garlic powder)

- 3 tablespoons of butter

- Salt to taste

- Epazote (optional or you can substitute it with bay leaves – her substitution, not mine. I wouldn’t use bay (laurel), I might use hojas de aguacate though)

- 5 cups water

To accompany

- Grated cotija (Queso cotija) or fresh cheese (Queso fresco) to taste

- Mexican cream (crema mexicana) to taste

- Mayonnaise to taste

- Lime (limón) juice to taste

- Chili powder or hot sauce to taste

Instructions

- Start by adding the butter, chopped onion and garlic to a pot and sauté until translucent. Add the corn kernels and cook for 5 minutes at medium temperature. Add the water, epazote and salt. let it boil for 20 minutes.

If you are using a rama (or sprig) of epazote or bay leaves (or hojas de aguacate) remove the sprig/leaves before serving. You don’t eat either the bay or the aguacate leaves. The epazote can be eaten (although scoffing a branch of it would be unpleasant). Some recipes call for the epazote to be chopped before adding and cooking it. In this case you would most certainly eat it.

Pati Jinich expands on this receta.

Esquites (Pati Jinich)

- 2 tablespoons unsalted butter

- 1 tablespoon vegetable oil

- 1 serrano or jalapeño chile, chopped (optional – include the seeds) or more to taste

- 8 cups of kernels from about 12 fresh corn

- 2 cups of water

- 2 tablespoons of chopped fresh epazote or 1 teaspoon of the dried one, you can replace it with cilantro which, although it will give it a different flavour, also works. See **NOTES**

- 1 teaspoon salt or more to taste

- 2 limes cut into four (optional to accompany)

- 1/2 cup of mayonnaise or Mexican crema (optional to accompany)

- 1/2 cup crumbled fresh cheese or cotija

- Chile piquín powder (optional to accompany)

Method

- Heat the butter and oil in a large pot over medium-high heat. When the butter melts and begins to bubble, add the chopped chili and cook for 1 minute, stirring frequently until softened.

- Add the corn and cook for a couple more minutes. Pour the water into the pot, add the epazote or cilantro and the salt. Stir and let it come to a boil, cover, reduce the heat to medium-low and cook for 12 to 14 minutes, until the corn is completely cooked. Put out the fire. You can leave the corn in the pot for a couple of hours.

- Serve the esquites in small cups or bowls. Let everyone add lime juice, mayonnaise and/or cream, cheese, chile piquín and salt to taste.

This recipe is to prepare esquites in the central Mexican style. In other states of the country, onion, epazote, serrano or jalapeño peppers are not used

***NOTES** Pati notes using cilantro in this dish. If you’re using cilantro I would recommend using the (well rinsed) roots rather than the leaves. The leaves are delicate and the flavour is ephemeral. Cooking it in simmering/boiling water for nearly 15 minutes will decimate the flavour of the delicate leaves. The roots stand up well to being cooked, or you could use culantro which is very similar in flavour profile to cilantro and readily withstands cooking (in fact it seems to prefer being cooked)

Investigate culantro here….Culantro : A Cilantro Mimic

Now, I swear somebody bought up witches earlier?

One of the “secret ingredients” in prehispanic esquites was the use of “esquite” salt that gave the dish an unmatched flavour. The town of Tequixquiac (in the State of Mexico) is one area where this highly valued “salt” was collected and is the source of this (and others too) towns name.

Check my Post Tequesquite for the culinary and medicinal uses of tequesquite “salt”

A little over 200 kilometres away in the State of Morelos we have the legend of the town Tequesquitengo.

Local legend has it that the Town Council prohibited the inhabitants from trading this valuable commodity and that only the cooks could handle and collect the seasoning, so that no one would steal the secret of their food.

A merchant offered Pedro Molesto, the town’s sorcerer, a substantial profit if he obtained un bulto de esquite (a bundle of esquite). To achieve this goal, one dark night, Pedro stalked and attacked a local cocinera by beating her head in with his cane, and then stole the bag of tequesquite she was carrying for the upcoming days work.

The inhabitants of the town found the murdered body of the cook the next morning and found it suspicious that she was not carrying the tequesquite that she had gone out to collect.

They went to visit the local brujo Pedro Molesto to see if he could divine who the murderer was but much to their surprise he reacted violently to their visit and attacked them, even throwing the tequesquite that he had stolen as a weapon (they are “stones” after all?). Faced with such betrayal, the Town Council decided to kill the murderous and traitorous sorcerer. They tied him to a post in the centre of the town, next to the Chapel of San Juan Bautista temple, ready to burn him alive .

(I couldn’t find any pre-curse images)

They say that among his clothes he brought his most valuable witchcraft amulet, a small bottle containing sea water. When they set the bonfire ablaze, the brujo began to utter his curse and, after the fire had completely burned out they found, among his charred bones, a small bottle containing sea water. Once the bottle had been opened (to determine what lay within it I suspect) water began to flow from the bottle, increasing in volume until a flood consumed the entire town and turned it into what is now Lake Tequesquitengo .

Another more prosaic (1) explanation is that, during the time of the Porfiriato (2), towards the 19th century, the San José Vista Hermosa Hacienda became the richest in the region and monopolized the production and processing of sugar cane. The owners of this hacienda were the brothers Miguel and Leandro Mosso. Apparently, the indigenous population of Tequesquitengo at that time refused to work harvesting sugar cane for the new and despotic landowners. They were actually quite happy to continue harvesting tequesquite as they had been doing for time immemorial. The farmers offended the owners of the hacienda, who, as a form of retaliation ran their irrigation water into the lake which slowly raised the level of the lake and, after a period, flooded the entire town. This flooding occurred over the course of several years and there is a rumour that the final flood came from the occurrence of an earthquake that cracked the ground and allowed a greater influx of surrounding water sources.

- commonplace, unromantic. My apologies if I’m explaining something already known. I sometimes come across (and use) words that I feel that I know what they mean without being able to actually verbally explain that meaning. When this happens I tend to drop in an explanation of the word as a type of memory trigger for myself.

- the period of Porfirio Díaz’s presidency of Mexico (1876–80; 1884–1911), an era of dictatorial rule. Diaz suppressed the civil liberties guaranteed in the Constitution of 1857, and evicted literally millions of Mexicans from their lands and homes to make way for commercial developments. There was also great modernization during this period.

Another legend states that after a strong earthquake the town was flooded “overnight” thus converting Tequesquitengo to ” the Atlantis of Morelos .” In modern times the ruins of the town (or the chapel) might be seen during drought periods when the water levels of the lake are at their lowest. One of the tourist attractions of Tequesquitengo is scuba diving to explore the ruins of the submerged town.

Enough brujeria. Lets get back to the food.

Now I know this is a Mexican dish but…..let’s Mexicanize it even further

From the Doritos website

Ingredients:

- 4 ears fresh corn, shucked

- ¼ cup mayonnaise

- ¼ cup Mexican crema

- Salt to taste

- ½ cup Cotija cheese, crumbled

- ¼ teaspoon ancho chile powder

- 1 tablespoon cilantro, chopped

- lime, sliced in wedges

- 1 bag DORITOS® Flamin’ Hot® Limon Flavored Tortilla Chips, 9.25 oz bag

Method

- Grill corn until cooked through and charred on all sides.

- Slice corn kernels from cob with a sharp knife.

- Stir corn kernels with mayonnaise and crema. Add salt to taste.

- Scoop corn into serving dish.

- Top corn with Cotija cheese. Sprinkle with chile powder. Garnish with cilantro and lime wedges.

Serve with Doritos® Flamin’ Hot® Limon chips

…..or we could take it a step further like the crew at Pinche Elote

References

- Acevedo López y de la Cruz, Santos (2007) Xochimilco. Su historia. Sus leyendas. Ediciones Navarra/Patronato para el rescate del centro histórico de Xochimilco, A.C./Compañía Artística TLATEMOANI, México.

- Cline, S.L. (1986) Colonial Culhuacan, 1580-1600: A Social History of an Aztec Town : Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press

- Colaboración (2021) : MUJERES DE LA CAPITAL PARTE I: MUNDO PREHISPÁNICO Y VIRREINAL – WOMEN OF THE CAPITAL PART I: PRE-HISPANIC AND VICEREGAL WORLD : https://revistabaladi.com/2021/03/09/mujeres-de-la-capital-parte-i-mundo-prehispanico-y-virreinal/

- CONGRESO DE LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO : I LEGISLATURA : COORDINACIÓN DE SERVICIOS PARLAMENTARIOS : ESTENOGRAFÍA PARLAMENTARIA (SEGUNDO PERIODO DE SESIONES ORDINARIAS PRIMER AÑO DE EJERCICIO) : VERSIÓN ESTENOGRÁFICA DE LA SESIÓN ORDINARIA CELEBRADA EL DÍA 21 DE FEBRERO DE 2019 : Presidencia del C. Diputado José de Jesús Martín del Campo Castañeda : https://www.congresocdmx.gob.mx/media/documentos/39f6445fcda5df2d0db54d0a07496f9fbdef8e77.pdf

- Daneels, Annick. & Gutiérrez Mendoza, Gerardo (2012) El poder compartido “Ensayos sobre la arqueología de organizaciones políticas segmentarias y oligárquicas” (Shared power “Essays on the archeology of organizations segmental and oligarchic policies”

- de la Rosa, Edmundo López. (2016) “Anales De Culhuacan.” Anales de Culhuacan

- de Molina, Alonso (1571) Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, part 2, Nahuatl to Spanish, f. 22v. col. 2.

- Duran, D (1967) Historia de las indias de Nueva Espana (Tomo II). A.M. Garibay K. (Ed.) Mexico: Porrua

- Galindo, Roberto & Bandy, William & Mortera, Carlos & Ramírez, José. (2013). Geophysical-Archaeological Survey in Lake Tequesquitengo, Morelos, Mexico. Geofísica Internacional. 52. 21. 10.1016/S0016-7169(13)71476-4.

- Karttunen, Frances (1992) An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl : Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992)

- Mathiowetz, M. D., & Turner, A. D. (Eds.). (2021). Flower Worlds: Religion, Aesthetics, and Ideology in Mesoamerica and the American Southwest. University of Arizona Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1khdqp3

- McNeil, Cameron L.. (2012). Recovering the color of ancient Maya floral offerings at Copan, Honduras. Res: Anthropology and aesthetics, 61-62(), 300–314. doi:10.1086/RESvn1ms23647837

- Robelo, Cecilio Agustin (2018) Diccionario de Aztequismos, ó Sea Catalogo de las Palabras del Idioma Nahuatl, Azteca ó Mexicano, Introducidas al Idioma Castellano Bajo Diversas … al Diccionario Nacional (Classic Reprint) ISBN 10: 0428332226 ISBN 13: 9780428332228

- Schroeder, Susan (1991). Chimalpahin & the Kingdoms of Chalco. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Sullivan, Thelma (1980) “Tlatoania and tlatocayotl in the Sahagún manuscripts,” Estudios de Cultura Nahuatl 14

Websites

- cihuapilli. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/cihuapilli

- Esquites (Pati Jinich) – https://patijinich.com/street-corn/

- Esquites Doritos receta – https://www.tastyrewards.com/en-us/recipes/doritosr-esquites

- Esquites Mexicanos (My Latina Table) – https://www.mylatinatable.com/authentic-mexican-esquites-mexican-corn-salad/

- izquitl. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/izquitl

- Mexican Street Corn Salad: el Restaurante (Mexicano) Magazine – https://elrestaurante.com/recipes/seafood/slow-roasted-alaska-king-salmon-with-mexican-street-corn-sal/

- Receta de los esquites Morelenses – https://www.tvazteca.com/aztecauno/venga-la-alegria/la-cocina-de-venga-la-alegria/notas/receta-de-los-esquites-morelenses-venga-la-alegria

- Tequesquite – Archive of the Augustinian Province of Michoacán – https://apami.home.blog/2019/12/04/las-puchas-y-la-conquista-panera-de-mexico/

- tlazo-. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tlazo

- tlazolli. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tlazolli

- tlazolli. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tlazolli-0