The beverage, bate, is a traditional beverage of the state of Colima made from toasted and ground chan, beaten with water and sweetened with honey or a kind of molasses prepared from piloncillo, or hard brown sugar. The chan seed is an interesting pseudograin that hails originally from the Mexican state of Colima.

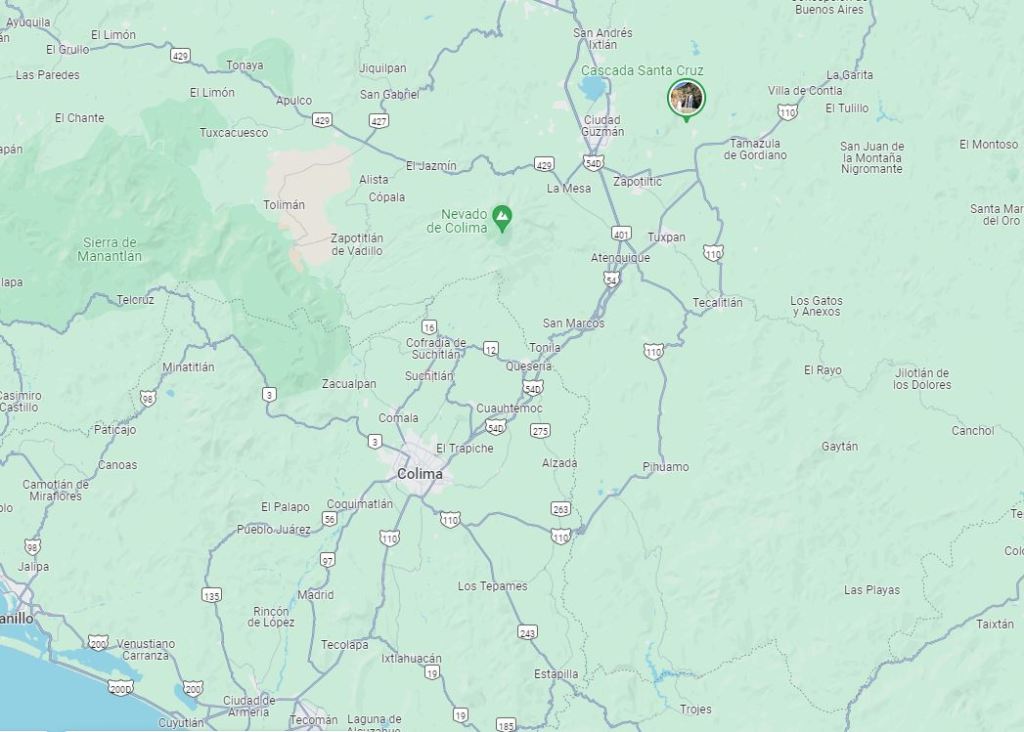

Suchitlán is a small town around 20 kilometres outside of the state capital of Colima (also called Colima or more officially the Free and Sovereign State of Colima (Estado Libre y Soberano de Colima) on the foothills of the state’s namesake volcano and is the venue for todays adventure.

Here begins the modern history of a prehispanic drink known as bate

The importance of this drink is such that, in 2011, the artist Gil Garea created a sculpture called the “bate seller” that can now be admired in the city of Colima. This figure pays tribute to Doña Cipriana Ascencio, a woman who inherited the knowledge to make this drink from her ancestors and dedicated her entire life to selling it on the corner of Calle Francisco I. Madero and Revolución where they intersect at the corner of Colima’s Jardín Nuñez near the La Merced church.

(noted as vendedora de bate – Click on Image to expand)

Today, it is her daughters and granddaughters who continue to keep her legacy alive.

Erected in honour of Doña María Cipriana Ascencio Dolores

After harvesting, the seed used to make this drink, chan, is roasted, ground and sold in powder or as prepared bate.

“To clean them, put the dried seeds on a plate and winnow them. All of the little dust goes away in the wind. Then you must toast them on a fire until the seed takes on a golden colour.” Doña Cipriana affirms that the secret in its flavour is found in the level of golden toastiness imparted to the chan during this process (el secreto en su sabor se encuentra en el nivel del dorado del chan). “If it is roasted too much, its flavour changes and becomes bitter.” Palmer (1891) notes that the “aromatic qualities” of the seeds are largely destroyed by cooking them but that their mucilaginous quality is largely developed and that they make “an even greater quantity of mucilage (1) when wetted”. Palmer notes that “Among the Indians it is called “Chan,” and to the attolle (sic) or gruel made by mixing it with corn they apply the name “Bate.” He then goes on to say “It makes a rather tasteless dish unless a little salt is added, or, as the Indians remedy the defect, a syrup made from sugar is sprinkled over it.”

- Mucilage : a polysaccharide substance extracted as a viscous or gelatinous solution from plant roots, seeds, etc.. Mucilaginous herbs derive their properties from the polysaccharides they contain. These polysaccharides have a ‘slippery’, mild taste and swell in water, producing a gel-like mass that can be used to soothe and protect irritated tissues in the body, such as dry irritated skin and sore or inflamed mucous membranes.

Once toasted, grind the seeds in a mill only used for chan.

“You then mix the powder with fresh water and whip it. That’s where the drink gets its name, from batir, Spanish for “to agitate” or “churn.”

The original recipe called for pinole and agave honey, but now the panocha is used without the pinole. In Zapotitlan de Badillo, south of Jalisco, and in Ticla, Michoacan, it is still prepared with pinole.

Sometimes other ingredients such as cocoa, cinnamon, chia seeds, vanilla, or other spices are added.

Ingredients

100g dry chan seed

1lt water

350g grated panocha

1 cup of water to dissolve the panocha

In a frying pan, place the chan seed and toast over medium heat. Avoid burning it so that the drink does not take on a bitter taste. Remove from heat and let cool.

Place the toasted seeds in a blender and grind until you obtain a fine powder. Pour into a bowl and set aside.

In an olla or appropriate container, place two litres of water along with the chan powder, mix perfectly until it thickens, store in the refrigerator and set aside.

The drink tastes similar to ones made from chia and has a slightly more bitter and toasted flavour. But, much like another drink maligned for the same reason (pulque) bate is notorious for its texture. Many have tried chia as a drink. When soaked in water, the seeds become somewhat gelatinous. Chan seed, when ground into a rough powder and rehydrated, transforms the water into a morass of gelatinous sludge; a watery suspension of coagulated chan. For some, this slimy and stringy consistency is a major turnoff. But you can chew the drink a little and push gelatinized chunks around with your tongue. The texture makes it more interesting. And in the Colima heat, the gooey, toasted drink quenches thirst. It’s kept on ice and the chan retains a cool, natural tone.

This bate is stored in a dried gourd for service. You can use a clay olla (or even a glass jug). Traditionally the container in which the bate is prepared is called a balsa (Balsa de calabazo) and the drink was served in jicaras (although a plastic cup is more likely these days)

Jicaras are a type of drinking cup made from a dried gourd. They can be plain or decorated.

There is apparently a happy middle ground

As you order your cup (or traditionally a jicara), the vendor will ladle out the thick, greyish liquid and top it off with a float of piloncillo molasses.

Panocha (or piloncillo)

Piloncillo is simply sugar cane juice reduced to a thick, crystallized syrup that is then poured into cone shaped moulds and dried. It’s full of impurities that impart a deep rum flavour with earthy notes of smokiness and caramel. Piloncillo comes in two varieties, light (blanco) and dark (oscuro). It’s not as sweet as regular white sugar but certainly has a lot more character. Traditional brown sugars have many different local names worldwide: They are called muscovado in Mauritius and the Phillippines, rapadura in Brazil, panela in Colombia, kokuto in Japan, and jaggery in India. All are suitable for this recipe.

Blanco piloncillo is made from green sugarcane, while oscuro is made from purple sugarcane.

As for the piloncillo “molasses”

Making piloncillo syrup is a simple task. All you really need is just the sugar and some water.

Ingredients

- 1x 8 ounce (approx 230 grams) cone of piloncillo

- 1 cup water

Optional – Spices can be used to give a flavour to your syrup.

Try using

- 1 star anise or

- 1 x 5cm stick of cinnamon or canela or

- 1 cinnamon stick and a few strips of orange peel

- 3 cloves

- (or any combination of the above)

Method

In a heavy-bottomed small saucepan place the water, add the piloncillo, and spices (if using) and, over medium heat, stir constantly while breaking down the cone with a wooden spoon. You can speed this process up by grating the piloncillo before adding it to the water.

Once the sugar dissolves, turn down the heat and let the syrup simmer steadily until it becomes a slightly thick syrup (somewhere between maple syrup and honey in viscosity). Cool before using.

That’s it. Pretty simple really

Back to the bate.

SIC Mexico (the Sistema de Informacion Cultural) in their Inventario del patrimonio cultural inmaterial (Inventory of intangible cultural heritage) notes that the cultural heritage of this plant and the drink made from its seeds is in danger of being lost as “The practice has been abandoned due to its consumption being reduced due to competition from other drinks. Chan is a wild, annual plant, and there are no formal cultivations of it.”

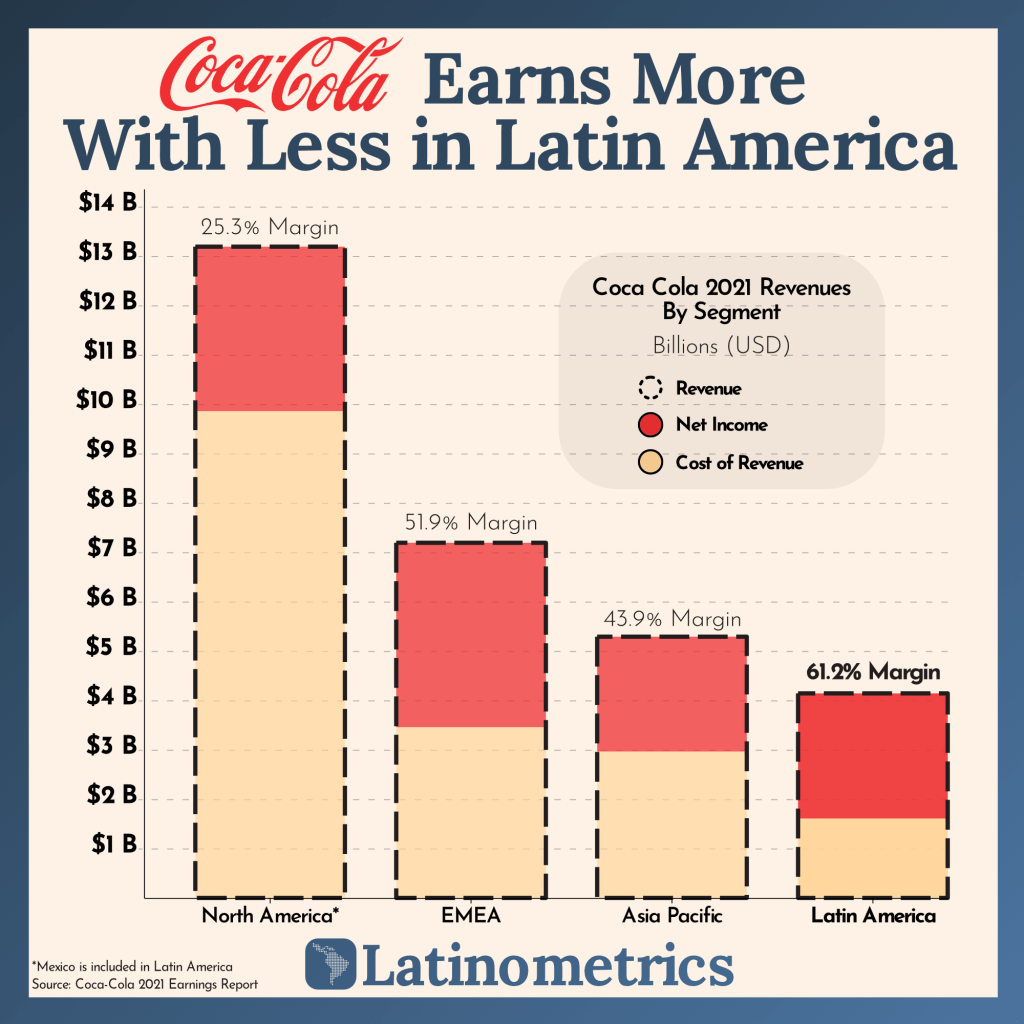

Here’s the main problem. Various figures range from 225 litres to 800 litres (in Chiapas – the highest consumption) per person per year being drunk in Mexico

“Mexico is the largest consumer of Coca-Cola in the world.” – https://worldmetrics.org/coca-cola-consumption-statistics/

225 litres – https://www.smigroup.it/repository-new/doc/ARCA_UK.pdf

803 litres – https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/with-average-daily-consumption-of-2-2-liters-of-coca-cola-chiapas-leads-the-world/

When purchasing your chan make sure you get the correct variety. Chia (salvia hispanica) is also often called chan

History of Bate

The biologist Aurora Montúfar López from the Laboratorio de Paleobotánica, Subdirección de Laboratorios y Apoyo Académico, INAH. (Paleobotany Laboratory, Subdirectorate of Laboratories and Academic Support) has studied chan and in her paper “Las chías sagradas del Templo Mayor de Tenochtitlan” establishes that the Nahua term chianzotzolatole implies the action of grinding or treating chan seeds to make the refreshing drink currently known as bate. She notes that In New Spain, at least two types of chia were used, one with small seeds and another with seeds like lentils (Hernández, 1959). In this regard, Manuel Orozco y Berra mentions two varieties: the black Chianpitzáhuac, and the larger white Chianpatláhuac.

Chia seeds were one of the most important grains for subsistence five centuries ago. Hernando Alvarado Tezozómoc (1994) mentions that chia was part of the provisions and speaks of the chia reserves: “…and a great many loads of cocoa, chili in bales and cotton in bales, other bales of seeds; loads of chian tzotzol and chian delgado, chianpitzahuac, huauhtli (1) and tlapalhuauhtli (2) seeds”

- huauhtli – amaranth

- Tlapalhuauhtli. (red huauhtli). A variety of xochihuauhtli (3) having reddish or rose-colored seeds.

- Xochihuauhtli – bledos amarillos. – yellow amaranth.

Aurora also notes that Sahagún (1979) speaks of the special care that was taken at the market; in one part, those who sold food were arranged: different types of corn and beans “… and white and black chian, and another that they called chiantzotzol .” Montúfar cites Alvarado Tezozómoc, who alludes to the concoction prepared with chian tzotzol to avoid feeling the heat of the sun and that now the bate – prepared and ingested in Colima – could correspond with that one (chiantzotzol). It is also noted that “Aguas prepared with chan are also useful for constipation and against bile.” Also, to “stimulate labor” and to” stop nosebleeds.”

The author stated that “infusions (aguas) of chan leaves and water prepared with its seeds serve against heartburn, stomach pain, fevers and for good digestion” and goes on further to say that “The decoction of its roots is useful for relieving kidney, gallbladder and liver discomfort.”

Chan is a seed akin to the chia but botanically unique. The usage of the term chan in Colima refers to the scientific species, Mesosphaerum suaveolens.

Mesosphaerum suaveolens (L.) Kuntze is an herbaceous plant belonging to the Lamiaceae family. The word “mesosphairon” comes from the Greek and Latin “mesosphaerum,” meaning “a type of tuberose with medium-sized leaves,” while its specific epithet suaveolens, means “with a sweet fragrance” due to the aroma of essential oils exhaled by the trichomes present on its leaves

Mesosphaerum suaveolens, synonym Hyptis suaveolens, is a branching pseudocereal plant native to tropical regions of Mexico, Central, the West Indies, and South America, as well as being naturalized in tropical parts of Africa, Asia and Australia

A pseudocereal (or pseudograin) is one of any non-grasses that are used in much the same way as cereals. Pseudocereals can be further distinguished from other non-cereal staple crops by their being processed like a cereal: their seed can be ground into flour and otherwise used as a cereal. The six main pseudocereals are…

- Amaranth : Amaranthus species (I have Posted on this one a number of times. Check out……Amaranth and the Tzoalli Heresy : Nutritional Profile of Amaranth : Medicinal Qualities of Amaranth : Recipe : Alegrias de Amaranto : Amaranth Joys.

- Quinoa : Chenopodium quinoa (I have Posted on a relative of this plant….check out….Quelite : Huauzontle

- Buckwheat : Fagopyrum esculentum

- Chia Seeds : Salvia hispanica

- Wattleseed : Acacia murrayana and A. victoriae (amongst others). This seed is a traditional foodstuff of the Australian aboriginal peoples. Specialised grinding stones (similar in nature to the Mexican metate) have been found in Australian archaeological sites that date back more than 65,000 years. Cooking Technique : Martajar

- Kañiwa : (also cañahua ) Chenopodium pallidicaule. Another of the Chenopodiums (C.album) commonly called fat hen also (mas or menos) falls into this category although its leaves would typically be eaten as a quelite. Quelites : Quilitl; although you are likely more familiar with its (probably) most popular cousin Chenopodium ambrosioides (although no longer called by this Latin nomenclature) Epazote…Quelite : Epazote

Mesosphaerum suaveolens

In the state of Colima, according to Vergara-Santana et.al (2005), three biological forms of H. suaveolens are located: the one that grows within the natural vegetation or wild form, a weed or hybrid form, sown by the agricultural and rare in natural vegetation, and the domesticated variety only present in cultivated fields.

This plant is widely naturalised in northern Australia (i.e. in northern and eastern Queensland, in the northern and central parts of the Northern Territory, and in northern Western Australia).

Synonyms : Hyptis suaveolens (L.) Poit.; Ballota suaveolens L.; Bystropogon graveolens Blume; Bystropogon suaveolens (L.) L’Hér.; Gnoteris cordata Raf.; Gnoteris villosa Raf.; Hyptis congesta Leonard; Hyptis ebracteata R.Br.; Hyptis graveolens Schrank; Hyptis plumieri Poit.; Marrubium indicum Blanco; Schaueria graveolens (Blume) Hassk.

Common Names : Confitura, confiturilla (Sonora y Sinaloa), conivaria, chan (Sonora), chana, chia gorda (Colima), chia de Colima (Jalisco y Colima), turturitillo, salvia blanca, chía (Guatemala), chia grande, Chinese mint, horehound, hyptis, mint weed, mintweed, pignut, wild spikenard

Indigenous names : La-pil (Chontal, Oaxaca), xol-té xnuk, cholte xnuuk, xoolte xnuuk, xote xnuuk.(Maya, Yucatán). Xóotle’xnuuk (Maya) (Duno y col., 2010); chan (Nicaragua, Pool, 2009); chichinguaste (Guatemala; Standley & Williams, 1973).

Chan is just a darker, wider and lesser known version of chia (Salvia hispanica). The black variety of the chan seed is the key ingredient in bate.

Salvia hispanica seeds

Mesosphaerum suaveolens seeds

“You have to grab the plant with gloves because they have a kind of rigid spine.” Say Doña María Cipriana Ascencio Dolores, (1) “ Inside of the burs, that’s where the chan seeds are.”

- A local vendor of bate who sold the drink for 50 years but unfortunatley passed away in 2018

Nutritional content of chan

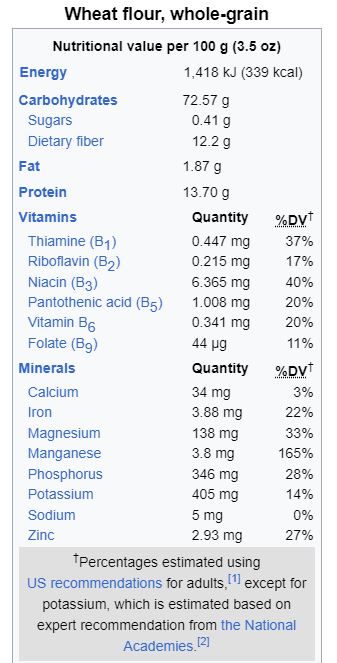

Chan seed flour has higher content of magnesium and calcium than either wheat flour or unenriched masa harina. It is higher in Phosphorous than masa harina (but not wheat) but has a lower content of Potassium than either of the other two grains. It is higher in protein content (per 100g dry weight) than wheat (but only marginally (13.9% as compared to 13.7% in wheat) and is almost double the protein content of unenriched masa harina (which comes in at 8.46% – according to the figures given by the US Dept of Agriculture)

https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/169696/nutrients

Medicinal uses of Mesosphaerum suaveolens

Medicinal actions (of whole plant) : allelopathic, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, carminative, emmenagogue (root decoction), febrifuge, insecticidal (essential oil), larvicidal, stomachic

Mesosphaerum suaveolens is an important source of essential oils, alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, saponins, triterpenes, and sterols.

Medicinal actions of the essential oils found in this herb which include…..Sabinene; Eucalyptol; E-Caryophyllene; Germacrene and β-Caryophyllene. Essential Oil Properties contains a little more information on the healing properties of these oils. : Antioxidant, antispasmodic, antiseptic, anti-cancer, anti-ulcer, antimicrobial, antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, anti-diabetic, anti-fertility, diaphoretics, anti cutaneous, anticatarrhal, antirheumatic, anti-ulcer, gastroprotective,

immunomodulatory, analgesic, and antiviral activity are all present in one or more of these compounds

In the Atlas of the plants of traditional Mexican medicine the most frequent use of the plant is to counteract diarrhoea and the way of preparation varies according to the region. In the state of Michoacán, for example, the decoction of the root is taken on an empty stomach; In Yucatán the infusion of the leaves is drunk.

In Brazil, the leaves in the form of infusions, decoctions, teas, and syrups are used to treat ulcers, inflammation, respiratory diseases (asthma, bronchitis, colds, flu, and sinusitis), diseases related to the gastrointestinal tract, pain, dizziness, nausea, nervousness, colic in babies, and constipation. The leaves are also used to treat headaches, malaria, fever, and used to reduce labour time and labour pain. The flowers of M. suaveolens are employed as therapeutic resources against dysmenorrhea, respiratory diseases, and as a febrifuge.

In India, the leaves, stems, inflorescence, and roots are used to treat urinary calculi, stomach pain, healing, itching, boils, eczema, diabetes, pneumonia, and fever. The seeds of M. suaveolens are used to treat gynecological disorders such as menorrhagia, leucorrhea, and rheumatism. The fresh poultice of the leaves is applied to snake bites, wounds, and mycoses, while the paste of the fresh leaves is also indicated for skin diseases

On the African continent, in Benin and Nigeria, the whole plant of M. suaveolens is used for the treatment of candidiasis and as a blood tonic

The seed oil

A high concentration of omega-6 lipids in the seed suggests chan oil to be an ideal product for dry, flaky skin and the treatment of eczema.

Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrum (GC-MS) analysis of the seed oil suggested high amounts (86.96 %) of unsaturated fatty acids: linoleic acid (76.13 %), oleic acid (10.83 %) compared to saturated fatty acids i.e. palmitic acid (6.55 %), stearic acid (4.56 %) and heptacosanoic acid (1.94 %) as the main constituents.

The oil (1 mg/ml to 0.125 mg/ml) was tested against various bacterial and fungal strains (Salmonella typhi MTCC 531, Pseudomonas aeruginosa MTCC 424, Lactobacillus plantarum MTCC 2621 and Candida tropicalis MTCC 229) at the lower concentration (0.125 %) and was found to be detrimental to the growth of these strains. Other strains tested (Escherichia coli MTCC 443, Shigella flexnerii MTCC 1457 and Vibrio vulnificus MTCC 1145) were found to be sensitive to the oil at higher concentrations (0.5 and 1 %) (Bachheti etal 2015)

References

- Agarwal K. and Varma R., Ethnobotanical study of antilithic plants of Bhopal district, Journal of Ethnopharmacology. (2015) 174, 17–24, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.003, 2-s2.0-84939163385.

- Aguirre-Mancilla, Cesar L. & Torres, Iovanna & Mendoza-Hernández, Guillermo & Garcia Gasca, Teresa & Blanco-Labra, Alejandro. (2011). Analysis of Protein Fractions and Some Minerals Present in Chan (Hyptis suaveolens L.) Seeds. Journal of food science. 77. C15-9. 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02480.x.

- de Albuquerque U. P., Monteiro J. M., Ramos M. A., and de Amorim E. L. C., Medicinal and magic plants from a public market in northeastern Brazil, Journal of Ethnopharmacology. (2007) 110, no. 1, 76–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2006.09.010, 2-s2.0-33846859517.

- Almeida-Bezerra, José Weverton, Rodrigues, Felicidade Caroline, Lima Bezerra, José Jailson, Vieira Pinheiro, Anderson Angel, Almeida de Menezes, Saulo, Tavares, Aline Belém, Costa, Adrielle Rodrigues, Augusta de Sousa Fernandes, Priscilla, Bezerra da Silva, Viviane, Martins da Costa, José Galberto, Pereira da Cruz, Rafael, Bezerra Morais-Braga, Maria Flaviana, Melo Coutinho, Henrique Douglas, Teixeira de Albergaria, Edward, Meiado, Marcos Vinicius, Siyadatpanah, Abolghasem, Kim, Bonglee, Morais de Oliveira, Antônio Fernando, Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Bioactivities of Mesosphaerum suaveolens (L.) Kuntze, Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2022, 3829180, 28 pages, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3829180

- Alvarado Tezozómoc, Hernando. 1609 Crónica Mexicayotl. Mexico City … 1994 Crónica Mexicana. Mario Mariscal Mexico City, D.F

- Bachheti, Rakesh & Rai, Indra & Joshi, Archana & Satyan, R S. (2015). Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Hyptis suaveolens Poit. seed oil from Uttarakhand State, India. Oriental Pharmacy and Experimental Medicine. 15. 10.1007/s13596-015-0184-8.

- Bernardino, de Sahagún, 1499-1590. (1979). Códice florentino. [México] :[Secretaría de Gobernación],

- Breitbach U. B., Niehues M., Lopes N. P., Faria J. E. Q., and Brandão M. G. L., Amazonian Brazilian medicinal plants described by C.F.P. von Martius in the 19th century, Journal of Ethnopharmacology. (2013) 147, no. 1, 180–189, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2013.02.030, 2-s2.0-84876144509.

- Cabezas Elizondo, Dora Argentina (2016) El tejuino, el bate y la tuba bebidas refrescantes: símbolos que perduran de generación en generación en el estado de Colima (Tejuino, Tuba and Bate Refreshing Beverages: Symbols that Endure from Generation) : Universidad de Colima, México : Primera Revista Electrónica en Iberoamérica Especializada en Comunicación http://revistas.comunicacionudlh.edu.ec/index.php/ryp

- Duno y colaboradores, 2010. Hyptis suaveolens. En: Flora de la Península de Yucatán, en línea (consultado 3/10/2011).

- Fanou B. A., Klotoe J. R., Fah L., Dougnon V., Koudokpon C. H., Toko G., and Loko F., Ethnobotanical survey on plants used in the treatment of candidiasis in traditional markets of southern Benin, BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies. (2020) 20, 288–318, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-020-03080-6.

- Ghalme R. L., Ethno-medicinal plants for skin diseases and wounds from Dapoli Tehsil of Ratnagiri district, Maharashtra (India), Flora Fauna. (2020) 26, 58–64, https://doi.org/10.33451/florafauna.v26i1pp58-64.

- Mapes, C., Basurto, F. (2016). Biodiversity and Edible Plants of Mexico. In: Lira, R., Casas, A., Blancas, J. (eds) Ethnobotany of Mexico. Ethnobiology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6669-7_5

- Martínez, M., 1979. Catálogo de nombres vulgares y científicos de plantas mexicanas. Fondo de Cultura Económica, México, D.F.

- Ngozi, L.. (2014). The Efficacy of Hyptis Suaveolens: A Review of Its Nutritional and Medicinal Applications. European Journal of Medicinal Plants. 4. 661-674. 10.9734/EJMP/2014/6959.

- Oliveira F. C. S., Vieira F. J., Amorim A. N., and Barros R. F. M., The use and diversity of medicinal flora sold at the open market in the city of Oeiras, semiarid region of Piauí, Brazil, Ethnobotany Research and Applications. (2021) 22, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.32859/era.22.21:1-19.

- Orozco y Berra, Manuel (1880) : Historia antigua y de la conquista de México : México, Tip. de G.A. Exteva

- Palmer, Edward (1891) An Historic Article on the Use of Chia Seeds by Indians and Mexicans in 1891: Published by Zoe Pub. Co., 1891

- Paulino R. D. C., Henriques G. P. d. S. A., Moura O. N. S., Coelho M. D. F. B., and Azevedo R. A. B., Medicinal plants at the sítio do gois, apodi, rio grande do norte state, Brazil, Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. (2012) 22, no. 1, 29–39, https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-695×2011005000203, 2-s2.0-83155182042.

- Ribeiro R. V., Bieski I. G. C., Balogun S. O., and Martins D. T. d. O., Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by ribeirinhos in the north araguaia microregion, mato grosso, Brazil, Journal of Ethnopharmacology. (2017) 205, 69–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2017.04.023, 2-s2.0-85018764259.

- Santamaría, Francisco Javier : Diccionario de mejicanismos : razonado, comprobado con citas de autoridades, comparado con el de americanismos y con los vocabularios provinciales de los más distinguidos diccionaristas hispanamericanos

- Sharma J., Gairola S., Sharma Y. P., and Gaur R. D., Ethnomedicinal plants used to treat skin diseases by Tharu community of district Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand, India, Journal of Ethnopharmacology. (2014) 158, 140–206, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.004, 2-s2.0-84910099724

- Silambarasan R. and Ayyanar M., An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Palamalai region of Eastern Ghats, India, Journal of Ethnopharmacology. (2015) 172, 162–178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.046, 2-s2.0-84936756236.

- Standley, P. C. y L. O. Williams, 1973. Labiatae. En: Flora de Guatemala. Fieldiana Botany 24, parte IX, 3-4.

- Vergara-Santana, M. I., Lemus-Juárez, S., & Bayardo-Parra, R. (5 de septiembre de 2005). http://www.ucol.mx Revista de investigación y difusión científica agropecuaria.

- Vidyasagar G. M. and Prashantkumar P., Traditional herbal remedies for gynecological disorders in women of Bidar district, Karnataka, India, Fitoterapia. (2007) 78, no. 1, 48–51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2006.06.017, 2-s2.0-33845393984.

Websites

- Atlas de las Plantas de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana, B. D. Medicina Tradicional Mexicana, UNAM. Obtenido de http://www.velvet.unam.mx: http://www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/monografia.php?l=3&t=&id=7152

- https://benditacomida.com.mx/2024/05/03/bate-bebida-colima-receta-forma-de-preparacion-historia-origen/

- https://drinkingfolk.com/bate/

Images

- Image – bate in Colima – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bate_en_colima.jpg

- Image – La vendedora de bate – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_vendedora_de_bate.jpg

- Image – El bate – Colima Sabe – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2903401656599966&set=a.1551668951773250

- Image – Colima Antiguo – https://www.facebook.com/Colima.Antiguo/photos/bate-bebida-elaborada-con-semilla-de-chan-especie-de-ch%C3%ADa-gorda-foto-secretar%C3%ADa-/755837931132307/?locale=es_LA

- Image SECTUR México – https://x.com/SECTUR_mx/status/1278436151448264711

- Image – Colima Algo nuevo por descibrir – https://i.pinimg.com/originals/84/26/82/8426827adee2d769b9dd2471af984ec5.jpg

- Image – Olla Mexicana – Guelaguetza Designs – https://conicear.best/product_details/94519323.html

- Image – Mesosphaerum suaveolens – By J.M.Garg – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5327119

- Image – Hyptis suaveolens plant (by Scamperdale) – https://www.flickr.com/photos/36517976@N06/5077779328

- Image – Mesosphaerum suaveolens seeds – (1)(2)(3) – https://furrloveov.best/product_details/70285281.html

- Image – Mesosphaerum suaveolens seed pods (Weeds of Australia) – https://keyserver.lucidcentral.org/weeds/data/media/Html/mesosphaerum_suaveolens.htm

- Image – Salvia hispanica – https://www.plant-world-seeds.com/store/view_seed_item/3649/salvia-hispanica-seeds

- Image – salvia hispanica seed – https://www.ayurtimes.com/chia-seeds-salvia-hispanica/ (2) By Magister Mathematicae – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15245222 (3) https://www.britannica.com/plant/chia

- Image – Salvia hispanica plant – https://lonestarnursery.com/products/chia

- Image – Salvia hispanica seed pods – https://ubernicear.live/product_details/3611578.html

- Image – Vampiros de San Luis Soyotlan – https://www.debate.com.mx/viajes/A-un-lado-cantaritos-El-Guero-Prueba-los-famosos-vampirosde-San-Luis-Soyatlan-20230908-0232.html

- Image – Chocomilk en Bolsa – Mexican Street Food Vendor – https://i.pinimg.com/originals/ea/70/5a/ea705a50351dd93cffc40b6f73c7db67.jpg

- Image – Jamaica (en bolsa) – https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=256720035739818&id=112475996830890&set=a.152400086171814

- Image – Tepache en bolsa – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=929642385830222&set=a.119538706840598