In August of 2024 I presented a talk at the West Australian Museum as part of a series delivered by FOMEX (The Friends of México Society) on the architecture of Mexico. This was the 3rd series of talks presented and is part of the Mission Statement of FOMEX which is to share the culture of their homeland with the society of the peoples they are now in. FOMEX does so much more than just this and tries to hold events for other significant moments on the Mexican calendar such as El dieciséis de septiembre (September the 16th the Día de la Independencia and the Grito de Dolores, commemorating the beginning of the fight for Independence in México), Dia de muertos (the Day of the dead – I dont think this one needs an explanation), El Día Del Niño (Childrens day) and others (hey any reason to get together to share food and camaraderie is a good one si?). These events are to educate the locals and to help keep alive the traditions in their own children who may have been born outside of México. In addition here in Perth we are also blessed to have available the maestro Ernesto and his Mexican Folkloric dance troupe Ixtzul which provides an even deeper understanding of México and her traditions through an array of regional Mexican dances.

This Post is part of my original talk (as is Part 3 : Colonial Californiano) which is just to expand on a few points I was unable to deliver in my all too short presentation. Now, to be fair, my background is not in architecture (I am a chef and herbalist by trade) and in my researching for the talk I quickly found that the subject was simply way to vast to be covered in a 60 minute talk and that I could easily study this subject for decades and write many theses as a result. Two areas I found compelling were Haciendas (and all that entailed, historically speaking) and the pre-Columbian inspiration for architecture since México gained independence for Spain.

If you missed my presentation I have posted it as Episode 1 so please check that out for more context on Episodes 2 and 3 otherwise please continue reading.

In a search for a national identity México has often looked to the pre-Colombian era for inspiration. During the porfiriato (1) the then current President, General Porfirio Díaz, did have a preference for European cultural norms but when the country was exhibited to foreign audiences the historical artistry of the Maya and Mexica were used to create interest in the country.

- the period of Porfirio Díaz’s presidency of Mexico (1876–80; 1884–1911)

World Expos

The Exposition Universelle of 1889, better known in English as the 1889 Paris Exposition, was a world’s fair held in Paris, France, from 6 May to 31 October 1889. It was the fifth of ten major expositions held in the city between 1855 and 1937. The Eiffel Tower was built to be one of the main attractions at the Paris World’s Fair in 1889.

The Mexican pavilion at this expo featured a model of an exotic (for Europeans) Aztec temple, a “combination of archaeology, history, architecture, and technology.”

Paris Exposition 1889

The palace was constructed to be reminiscent of the architectural style of the peoples that inhabited this particular region of the Americas before its discovery by Europeans.

M. Ramon Fernandez, the current Minister of Mexico in Paris at the time, did everything possible to induce his government to take part in this great manifestation of progress and to prove once and for all the strength of the friendship which united it with France. Its primary architect was also Mexican, Mr. Antonio Anza, who was assisted in his efforts by another Mexican architect, Mr. Luís Salazar.

This pavilion inspired the later construction of several monuments in Mexico.

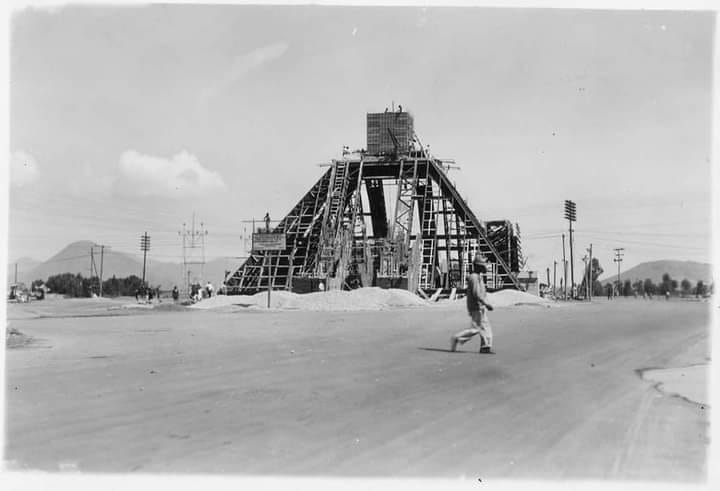

One of these was the Monumento a la Raza.

The Monumento a la Raza is a 50 meters (160 ft) high pyramid in Mexico City. Its construction started in 1930 and was completed ten years later. It was inaugurated in 1940, on the Día de la Raza (“celebrated” as Columbus Day in the U.S.), and it is dedicated to la Raza—the indigenous peoples of the Americas and their descendants.

It is located in the intersection of Avenida de los Insurgentes, Circuito Interior and Calzada Vallejo, in the Colonia Cuauhtémoc.

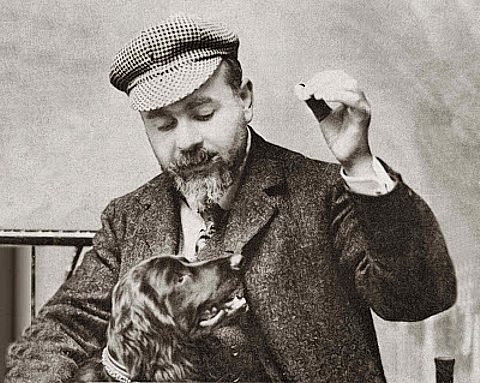

The monument consists of three superimposed truncated pyramids decorated with several sculptures on the sides and an eagle at the apex. The pyramid was designed by Francisco Borbolla and the stone sculptures and its layout by Luis Lelo de Larrea. Many of the artworks were created during the Porfiriato period. The copper-and-steel eagle was cast by French animalier Georges Gardet and the bronze high reliefs were created by Mexican sculptor Jesús Fructuoso Contreras.

The eagle was originally intended to be placed on top of the never completed Federal Legislative Palace, later replaced with the Monumento a la Revolución in downtown Mexico City, while the reliefs were based on those created for the Aztec Palace, presented in the Mexican pavilion of the 1889 Paris Exposition.

Jesús has been called the most “representative sculptor of late 19th century Mexico”

The pyramid of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacán. Teotihuacán is an archaeologically significant site. A city whose origin is not entirely certain and already lay in ruins by the time the Mexica entered the Valley it has a footprint of about 8 square miles and lays less than 50km from the heart of Mexico City. Its aesthetics have been a source of inspiration for the artistic for millennia.

Even though the Monumento a la Raza drew criticism from writers and historians for its choice of Porfirian components and it’s caricaturizing of Mesoamerican architecture it has inspired the naming of nearby constructions including the local metro station, a hospital, several hotels and the Atricenter La Raza (a rheumatologists office) amongst others.

The monument has been abandoned since at least 2022, as it has received minimal maintenance from the city government.

In 2023 the Mexican politician Martí Batres (interim head of government of Mexico City following the resignation of Claudia Sheinbaum) began pressuring the Federal government to take responsibility for the care and restoration of this monument and the surrounding areas.

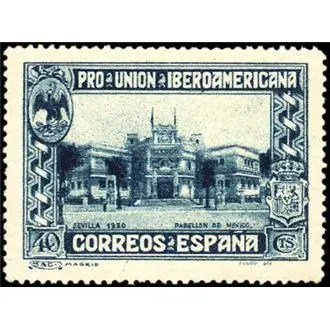

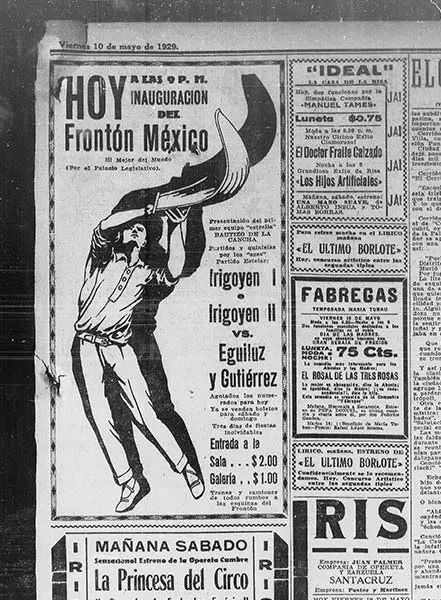

The Ibero-American Exposition of 1929

The Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 (Exposición iberoamericana de 1929) was a world’s fair held in Seville, Spain, from 9 May 1929 until 21 June 1930. The Mexican pavilion included exhibits on archaeology, education, and the history of Spanish accomplishments in Mexico.

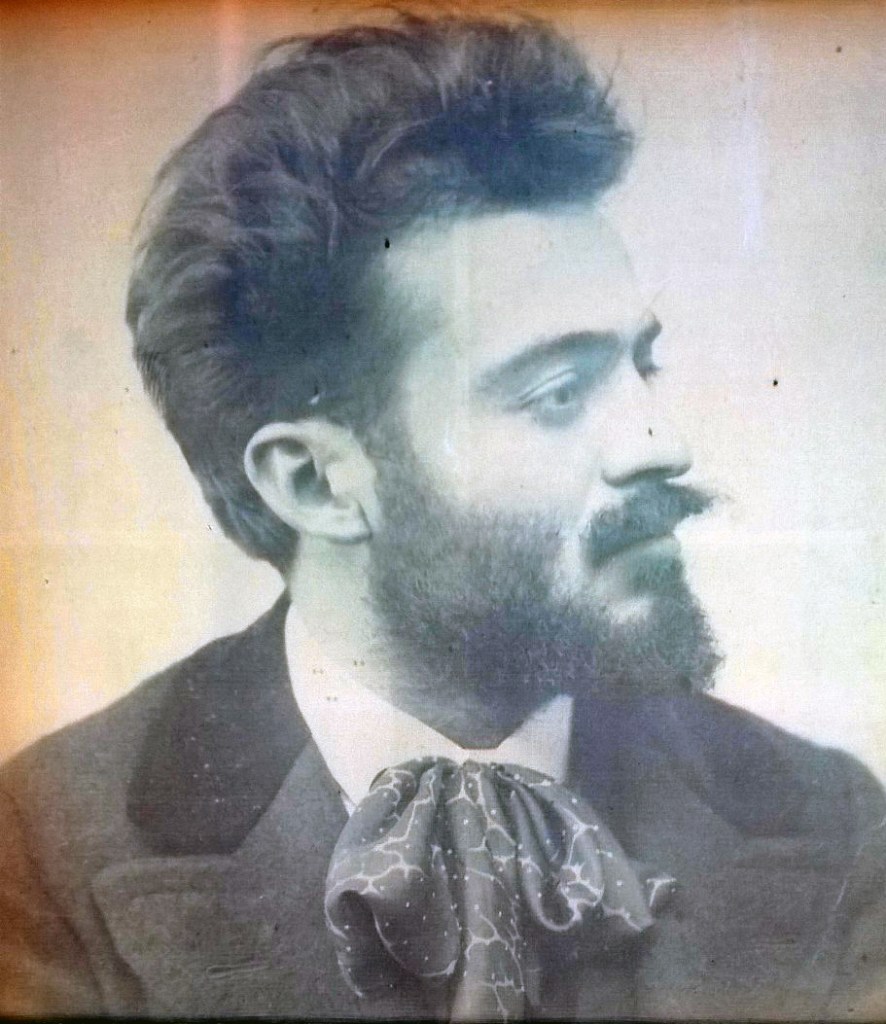

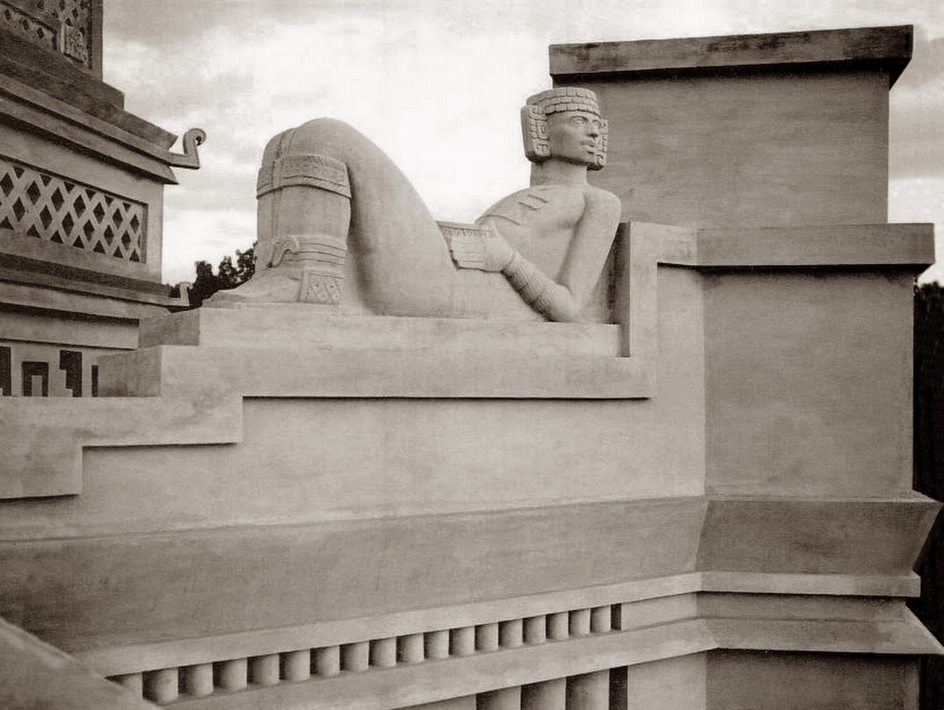

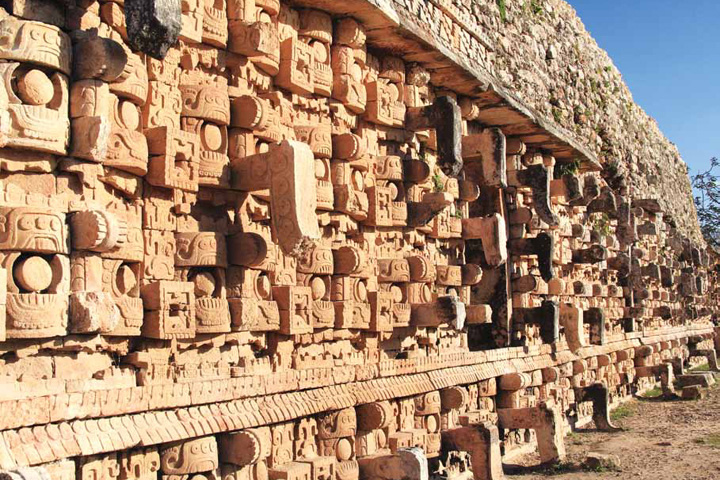

Students in Mexican schools prepared some of the education exhibits. Its architect was Manuel María Amábilis Domínguez, from Mérida, Yucatán, who proposed the project named “ITZA” in collaboration with two Yucatecan artists, Leopoldo Tommasi López (in charge of the sculptures) and Víctor Manuel Reyes (in charge of the drawings). The building is inspired on Mesoamerican architecture; specifically the Maya architectural style known as Puuc and the Toltec-influenced style of Chichen Itza, both found in Yucatán.

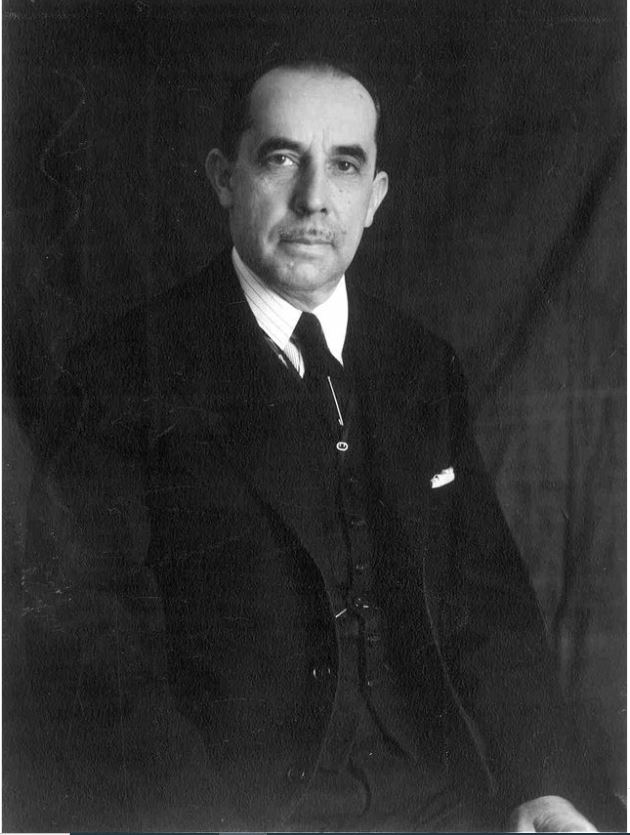

Mr. Manuel Amábilis Domínguez (1889 – 1966)

Examples of Puuc style from Uxmal.

Other imagery from the pavilion

The temple of Jaguars at Chichen Itza

Palacio Bellas Artes

The historical background of the Palacio dates back to February the 18th of 1842, when the then President of the Republic, Antonio López de Santa Anna, began the construction of the Santa Anna Theatre, the most important architectural work for the city in the 19th century.

Its construction can be divided into three stages that mark the transition from the Porfirian era to post-revolutionary Mexico,

- with the beginning of construction according to the plans of Adamo Boari (1904-1916),

- with suspension of works and the reconditioning of the building as a multi-purpose space (1917-1929 ),

- and then the resumption and conclusion of construction under the direction of Federico Mariscal (1930-1934).

The Palacio began its construction in 1904, during the last years of the government of Porfirio Díaz, who wanted to represent his motto “Order and progress” in a building that could be completed for the celebrations of the Centennial of Independence in 1910. The task was initially commissioned to the famous Italian architect Adamo Boari.

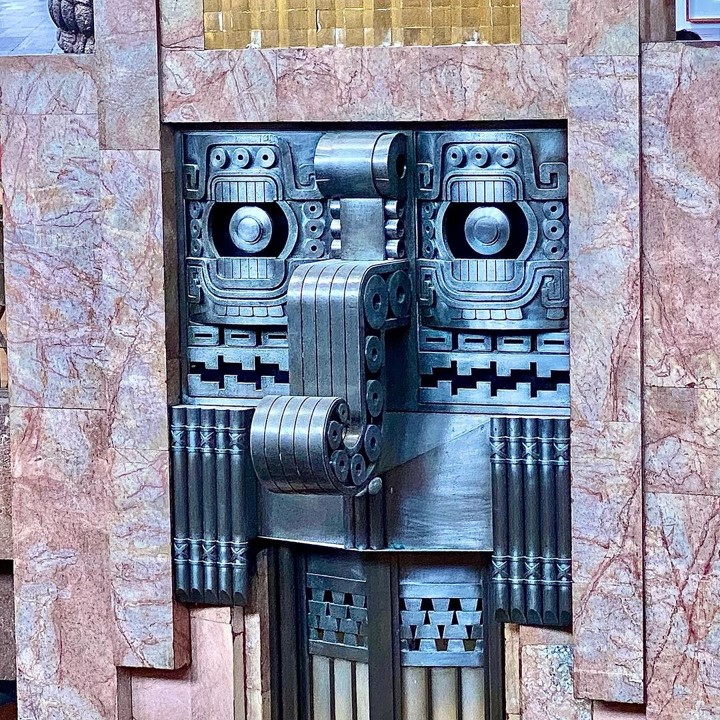

For the decoration, Boari considered that the enclosure should use and express architectural forms alluding to Mexican culture, which explains the inclusion of elements from pre-Hispanic culture such as the heads of jaguars, monkeys, coyotes, and snakes, which predominate on the facades.

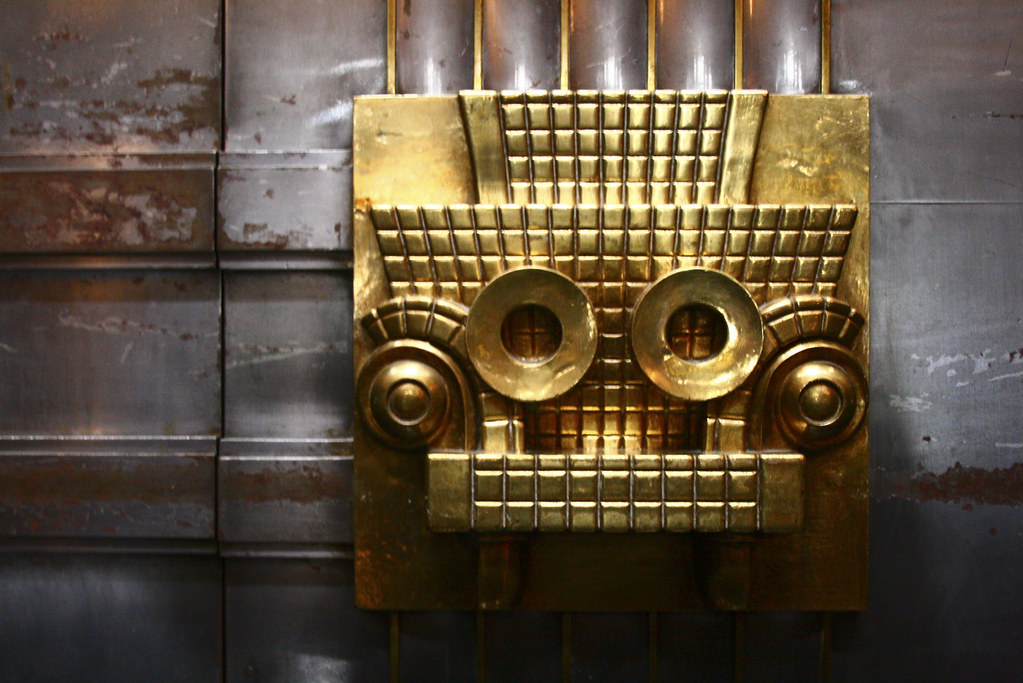

Chaac, the Mayan god of rain, gets an Art Deco makeover in some of the lighting fixtures of the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

In 1917 work was briefly paused (By 1916 the exterior was finished and the domes were being built when Boari had to leave the country due to the instability of the Mexican Revolution)

Between 1918 and 1919 an attempt was made to resume and complete the work within the presidential period of Venustiano Carranza under the direction of architect Antonio Muñoz. Both men wanted the work to be completed by 1921, but the serious social and economic problems of the time did not allow it and the work was abandoned. Between 1917 and 1930 no real advances in completing its construction were made.

This mask is said to be a representation of the Dios de lluvia (God of rain/the waters) Tlaloc although others argue that it represents Cipactli a primeval crocodile/fish/toad/demon god of creation. The design is taken from the façade of the temple of Quetzalcóatl in Teotihuacan.

If we are going to take this carving in context with Quetzalcoatl and creation myths surrounding him then this is likely a representation of Cipactli but we shall leave these distinctions and arguments to the scholars. All I’m interested in at this point is the iconography as inspiration.

In 1930, President Pascual Ortiz Rubio began work on the facility again through a decree in which he set two essential conditions; that the completion of the work was as economical as possible, and that the original plans of the Italian architect were respected as far as possible.

In 1932, via another presidential decree, an attempt was made again to complete the work. The new architect in charge was Federico Mariscal, who redesigned the interior of the theatre to the rules of the new fad sweeping the country, “Art Deco”, with elements inspired by Mexico’s “ancient past”.

The elite Mexica masked Eagle and Jaguar warriors adorning the Palacio.

The Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts) was inaugurated on September 29, 1934 by the then president Abelardo Rodríguez.

Artisan Architects

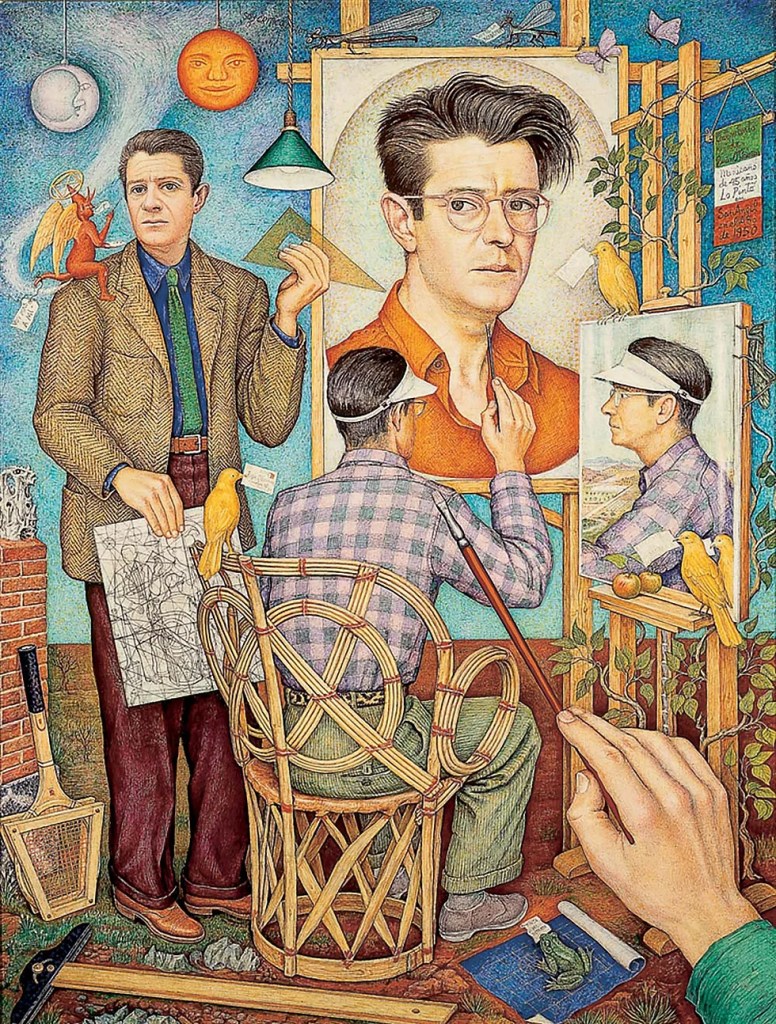

Diego Rivera (1886–1957)

Diego Rivera, was a prominent Mexican artist. Trained at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, he spent more than a decade in Europe (from the summer of 1911 until the winter of 1920), becoming a leading figure in Paris’s vibrant international community of avant-garde artists. After his return to Mexico in 1922, he joined fellow creative thinkers and state officials in concerted efforts to revitalize and redefine Mexican culture in the wake of the Mexican Revolution (1910–20). His large frescoes helped establish the mural movement in Mexican and international art.

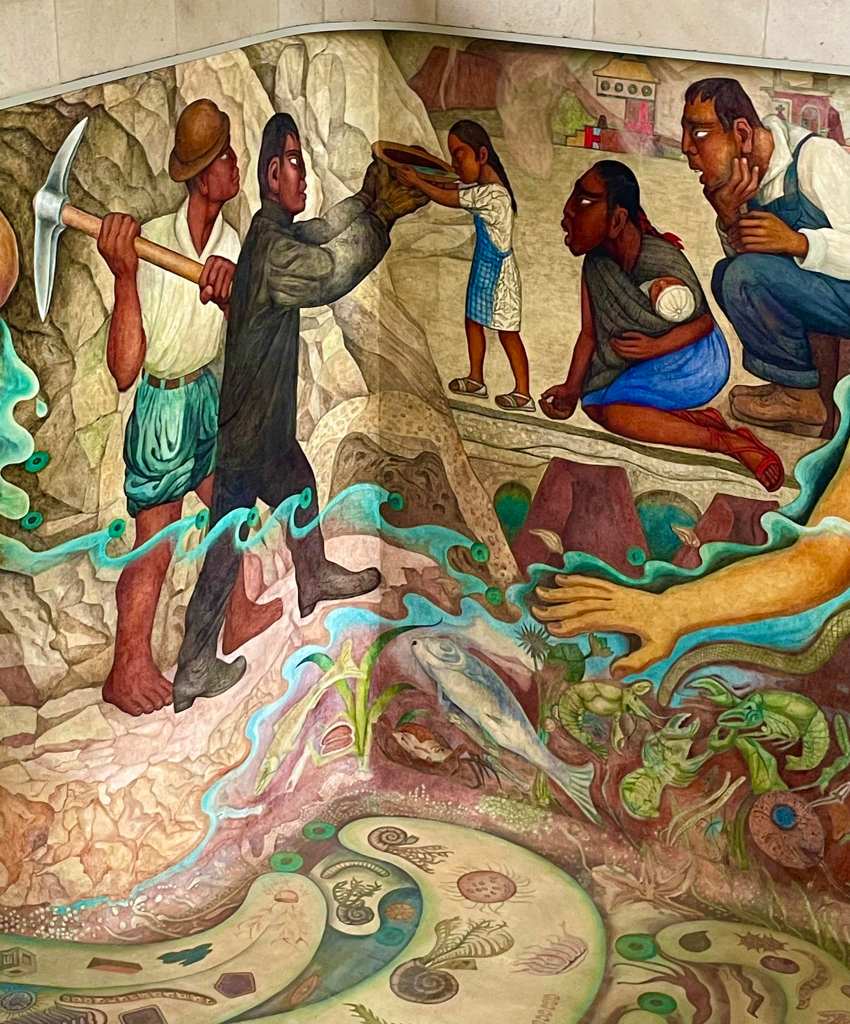

Only five years before his death, Diego finished one of his most intriguing works, la Fuente de Tláloc. Although strikingly different in medium from most of his work, the massive tiled fountain beautifully captures the essence of the Mexican spirit and art that is so often depicted in his paintings.

Known best for his murals, which he painted in Mexico, Europe and the United States, Rivera began a project in 1952 to improve the infrastructure of Mexico City, beginning with the municipal water system. Created at the head of the Lerma River leading out to the city’s reservoirs, Rivera created a massive tiled sculpture of the god of Rain, Tláloc, that spanned a pool 100 feet across.

Constructed lying on his back, water used to rush over the god Tláloc, until a pipe diverted the flow of water away from the fountain. Rivera’s work of art then slowly decayed until it was eventually closed off for over a decade at the turn of the century. Finally, in 2010, the fountain, murals and tile work were restored and visitors began to visit the unique Fuente de Tláloc.

Along with the fountain, Rivera also built and decorated the Carcamo, a massive tank that diverted water through the fountain, and was used to control water levels.

The Cárcamo de Dolores hydraulic structure, found in this section, was built between 1942 and 1952 to capture water sent to the Valley of Mexico from the Lerma River basin in the Toluca Valley. The major parts open to the public consist of a pavilion, covered with an orange half cupola and a fountain with an image of Tlaloc. Originally, the water was stored underground and pumped to the surface when needed. The main building has serpent heads on the four corners and there is a mural painted by Diego Rivera called El agua: origen de la vida

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (National Autonomous University of Mexico)

The National Autonomous University of Mexico is a public research university in Mexico which has several campuses in Mexico City, and many others in various locations across Mexico. It has 34 research institutes, 26 museums, and 18 historic sites. A portion of this Ciudad Universitaria (University City), UNAM’s main campus in Mexico City, and according to UNESCO “bears testimony to the modernization of post-revolutionary Mexico in the framework of universal ideals and values related to access to education, improvement of quality of life, integral intellectual and physical education and integration between urbanism, architecture and fine arts”. The Ciudad Universitaria is a registered UNESCO World Heritage site where more than sixty architects, engineers and artists worked together to create the spaces and facilities.

The urbanism and architecture of the Central University City Campus of UNAM constitute an outstanding example of the application of the principles of 20th Century modernism merged with features stemming from pre-Hispanic Mexican tradition.

UNAM was built on the site of the Xitle volcano, which erupted around 100 AD. Lava rocks from the volcano were used in in the construction.

Biblioteca Central UNAM

Central Library (UNAM Biblioteca Central), is the main library in the Ciudad Universitaria Campus of UNAM. The library opened its doors for the first time on April 5, 1956, after being moved from its original location in Mexico City centre, where it had been previously for 50 years.

Construction of the UNAM Central Library began 5 years earlier in 1950. Designed by the architect and painter Juan O’Gorman, it has been classified as a masterpiece of functionalist architecture ever since.

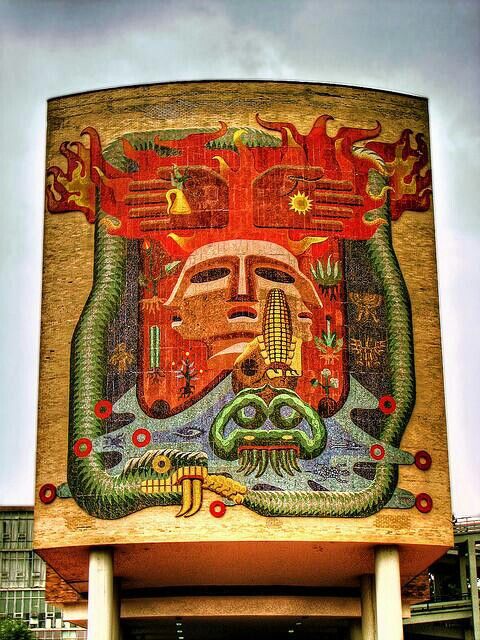

The northern entrance to the building is adorned with a fountain in the form of Tlaloc, a god of rain and fertility, a motif repeated in other parts of the building. Garden dividers on the ground-level bear reliefs of the silhouettes of the gods, Quetzalcoatl and Ehecátl (a god of the wind) and a mask surrounded by snakes.

If you haven’t already noticed the subject of Tlaloc recurs quite regularly in the artistic imagery leaned upon by most of the artists I have featured.

Tlaloc was an extremely important being in the mythologies of the Mexica. His shrine stood side by side with that of Huitzilopochtli (their main deity) atop the Templo Mayor in the heart of Tenochtitlan.

Tlaloc still resides at the heart of Mexico

The whole building is covered with a series of tiled murals. The idea for the murals was proposed by O’Gorman to Carlos Lazo (Manager of the Ciudad Universitaria project). Lazo was very excited, especially by the idea of making a mural made just out of thousands of colored tiles, something that never had been done at that scale. The tiles were brought from many different parts of the country because a large number of colours were needed for the construction.

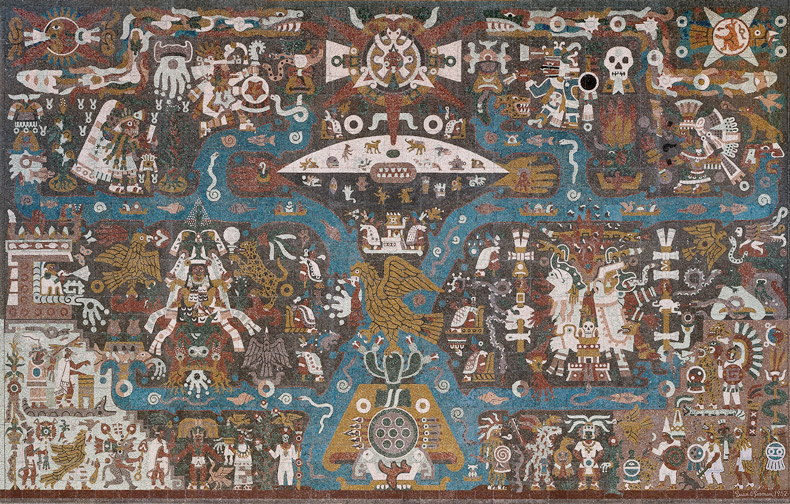

The north wall of the building represents images of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican cultures and their deities. The theme turns around a life-death duality. The north side is illustrated with the face of Tlaloc framed by a pair of open hands. Scenes of pre-Hispanic Mexico, including the founding of Tenochtitlan are also presented.

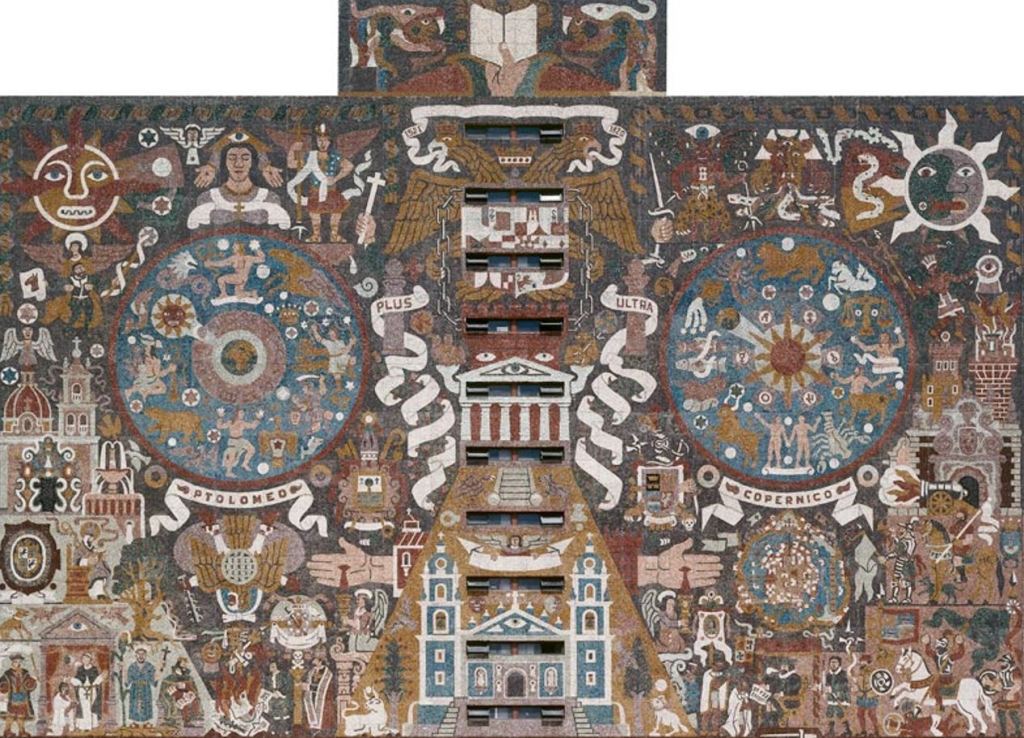

The east wall portrays Mexican modernity, with the Revolution as one of its themes. In the center, a model of the atom generates the principle of life. And the further duality of the moon and the sun look down from above.

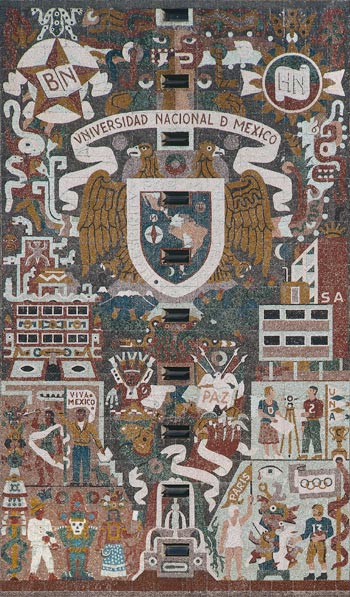

The west wall presents the National University in all its finery with the coat-of-arms holding the most central position. Other allegories and representations include the studies of science, culture, sports and engineering

The south wall depicts the arrival of the Spanish in Mexico and the Conquest, and a dual God and Devil. It also presents the physical trappings of that period of history, including churches, guns, maps, manuscripts and monks

Murals reside everywhere in the UNAM. They are part of the integration of “plastic arts” where popular art such as murals are integrated into the architecture of the building and in fact the building is designed in such a way to allow this as both the art and the architecture is a reflection of the human condition.

Los Frontones

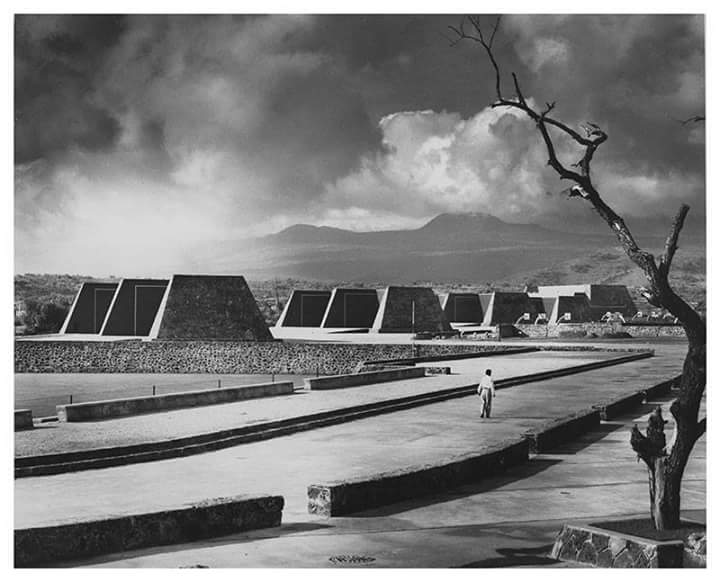

Alberto Teruo Arai Espinoza was born on 29 March 1915, in Mexico City to a Japanese diplomat father and Mexican mother. Arai trained at the UNAM School of Architecture, which then still had its headquarters at the Academy of San Carlos. In addition to being an architect, he was a thinker, critic and philosopher, all of which influenced his design at UNAM. Arai is remembered for being the creator of the design of los frontones of the Central Campus of the University City of UNAM, a complex inscribed on the World Heritage List of the UNAM. UNESCO since 2007.

The building of the Ciudad Universitaria, Mexico City, gave him his greatest architectural opportunity when he designed the “Frontones” de Ciudad Universitaria (1952). In these he used the volcanic stone of the area to great effect to create truncated pyramid shapes inspired by Pre-Columbian pyramids. This was his contribution to the early landscaping-architecture, by using the volcanoes surrounding the view as a theme for his design.

Located in the sports area of Ciudad Universitaria, los frontones are a set of reinforced concrete structures covered with piedra braza.

Stone material derived from breaking the rock called “andesite”

International fronton is sport that is played by striking a ball onto a wall with bare hands. The sport was created to bring together several aspects from wall ball sports such as American Handball, Basque Pelota, Gaelic handball and Valencian fronto), to be played at the annual Handball International Championships.

A fronton a building where pelota or jai alai is played (Pelota is a Basque or Spanish game played in a walled court with a ball and basket-like rackets fastened to the hand)

Espacio Escultorico

Created in 1979, the Espacio Escultórico designed by Helen Escobedo, Hersúa Sebastian, Federico Silva, Manuel Felguerez and Mathias Goeritz..

It is a circular structure with an outer diameter of 126 meters and an inner diameter of 98 meters, which comprises 64, 4 meters high concrete modules or pyramids built on the lava mantle left by the Xitle volcano eruption, which left a black lava mantle at the center. It is what remains from the great eruption of the Xitle volcano that once covered a big part of what is now the campus and where, before the eruption, the ceremonial centre of Copilco and the important city of Cuicuilco, of the Mesoamerican cultures, were found.

Located in the area of the University Cultural Center, this complex is a representation of the cosmos with pre-Hispanic references, surrounded by the Pedregal de San Ángel Ecological Reserve.

Public Spaces and Urban Architecture

Museums

Museo Anahuacalli

The Anahuacalli is a temple of the arts designed by the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera located in the San Pablo de Tepetlapa neighborhood of Coyoacán. Anahuacalli refers to the “House of Anahuac; ” Anahuac is the core of Mexico, the “Valley of Mexico” and is derived from the Nahuatl “house surrounded by water”/“Land on the Edge of the Water”

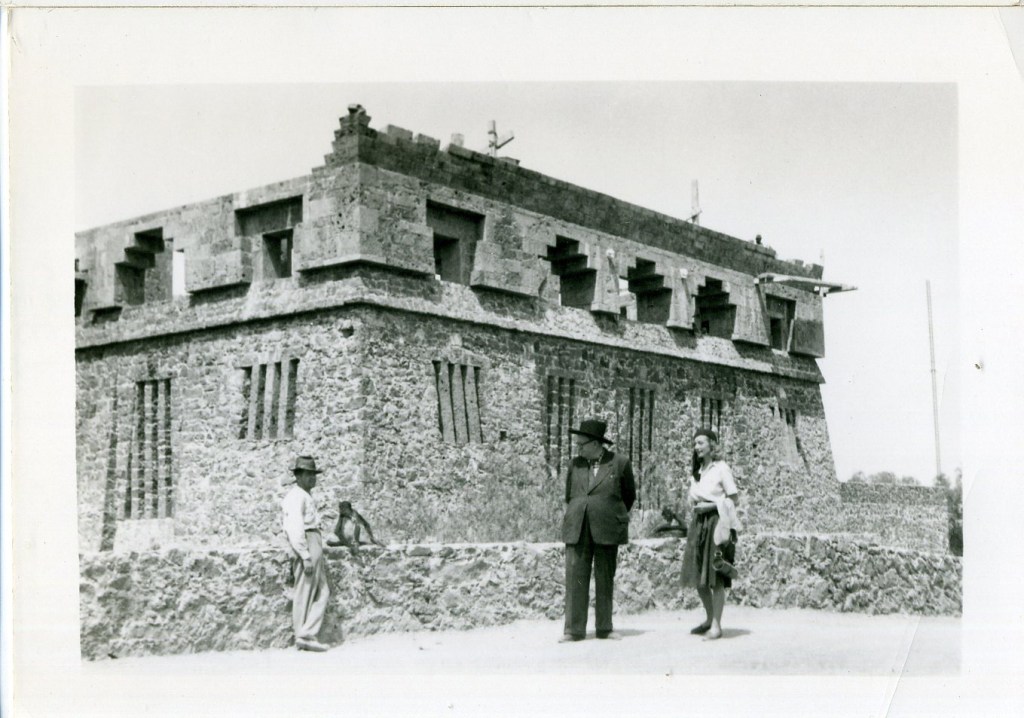

In 1941, upon his return from his trip to San Francisco, Rivera undertook the construction of this project, which sought to create continuity between modern art and pre-Columbian aesthetics. The painter chose the land of Pedregal de San Ángel, which had previously surrounded the Xitle volcano. He had acquired it, together with Frida Kahlo, with the aim of building a farm.

Construction of the Museo Anahuacalli began in 1942, but he died in 1957 and never saw its completion. His daughter, Ruth Rivera (1927–1969) together with the architects Juan O’Gorman (1905–1982) and Heriberto Pagelson, finished this project with the financial backing of María de los Dolores Olmedo y Patiño Suarez who was well known friend of both Diego and his tempestuous artisti lover Frida Kahlo. Dolores was the inspiration for some of Diegos paintings.

The Anahuacalli Museum building is erected with carved volcanic stone, extracted from the same place where it stands and the architecture of the building is inspired by Mesoamerican structures which Rivera defined as an amalgamation of Aztec, Mixtec, Zapotec, Toltec, and Mayan influences along with a “Traditional Rivera” style.

Diego was also keen on incorporating the environment surrounding the building as part of its architectural design.

Construction of the Anahucalli was completed in 1963 and the museum was inaugurated on September 18, 1964.

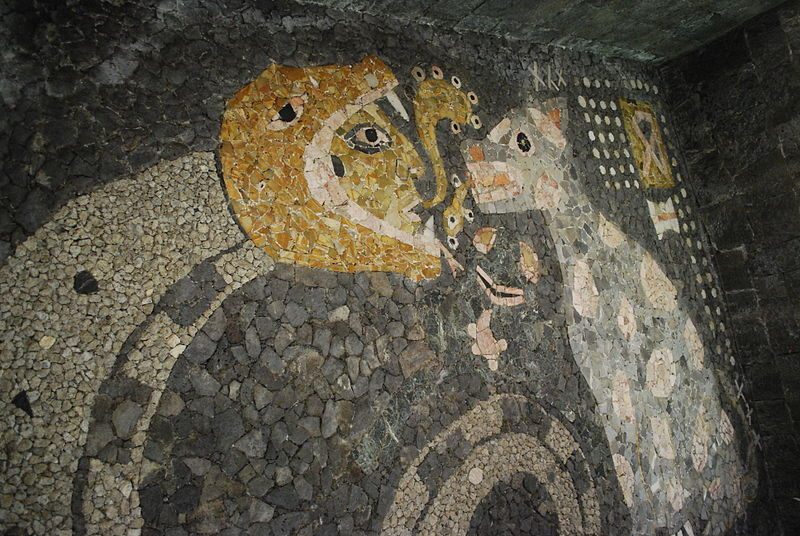

Intricate mosaics and artworks adorn the walls and ceilings of the museum

Rivera designed the building in order to safeguard his vast collection of pre-Hispanic pieces, while exhibiting the most beautiful works in the museum’s main building.

As a collector, Diego became fascinated with the pre-Colombian art produced by the Jalisco, Colima, Nayarit and Michoacán cultures of Western Mexico. These works revealed the everyday life of the people of that region and were the painter’s favourites. The Anahuacalli Museum contains more than 50,000 prehispanic pieces that the master muralist collected throughout his life and which he wanted to gift to the people of México as a tangible link to their prehispanic heritage. Two thousand of these pieces distributed amongst twenty-three rooms of the Anahuacalli comprise a permanent exhibition at the museo.

Diego still inhabits the museum, here sitting patiently at the ofrenda greeting all who visit.

Museo Nacional de Antropología

Museo Nacional de Antropología, is a national museum of Mexico. Located in the area between Paseo de la Reforma and Mahatma Gandhi Street within Chapultepec Park in Mexico City,

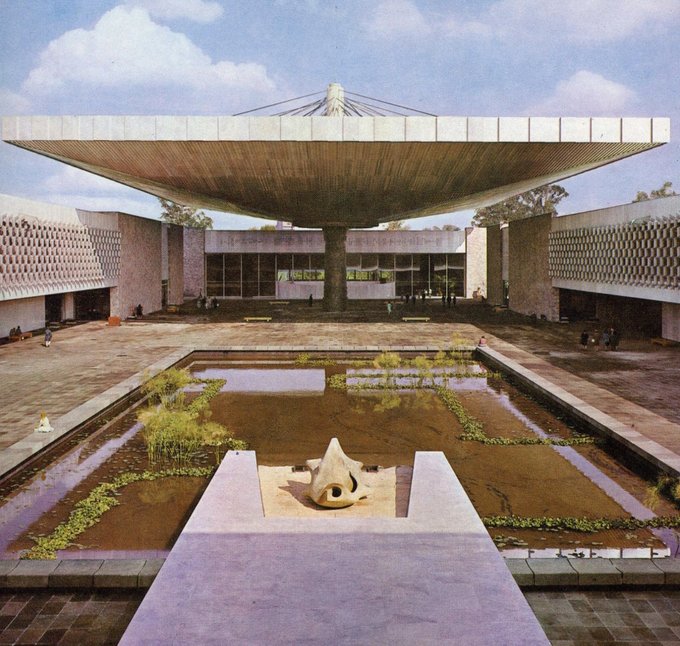

Designed in 1964 by Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, Jorge Campuzano, and Rafael Mijares Alcérreca, the monumental building contains exhibition halls surrounding a courtyard with a huge pond and a vast square concrete umbrella supported by a single slender pillar (known as “el paraguas”, Spanish for “the umbrella”).

The museum uses water architecturally as a metaphor of Anahuac, the land “between the waters” which represents the Valley of México itself.

Rufino Tamayo

Designed by the architects Teodoro González de León and Abraham Zabludovsky in the style known as “brutalist” architecture and built in 1981, the Rufino Tamayo museum sits at an important cultural crossroads in the Mexican capital – el Bosque de Chapultepec – just steps from the National Museum of Anthropology

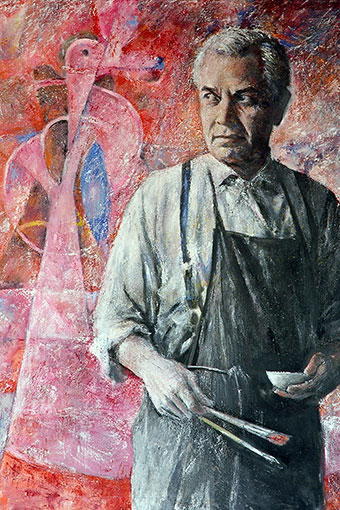

The Museo Rufino Tamayo is a public contemporary art museum that produces contemporary art exhibitions, using its collection of modern and contemporary art, as well as artworks from the collection of its founder, the artist Rufino Tamayo

Rufino del Carmen Arellanes Tamayo was a Mexican painter of Zapotec heritage, born in Oaxaca de Juárez, Mexico. Tamayo was active in the mid-20th century in Mexico and New York, painting figurative abstraction with surrealist influences

Prehispanic Brutalism

Brutalist architecture is an architectural style that emerged during the 1950s in the United Kingdom, among the reconstruction projects of the post-war era. Brutalist buildings are characterised by minimalist constructions that showcase the bare building materials and structural elements over decorative design

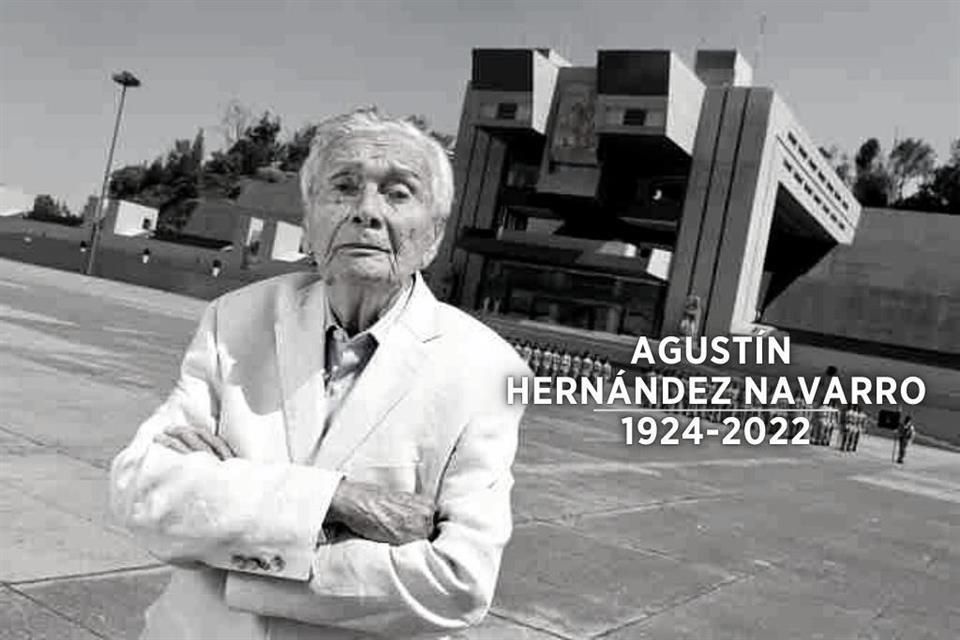

“The architect Agustín Hernández studied at the UNAM National School of Architecture and is considered one of the clearest exponents of modern Mexican architecture.

Praxis

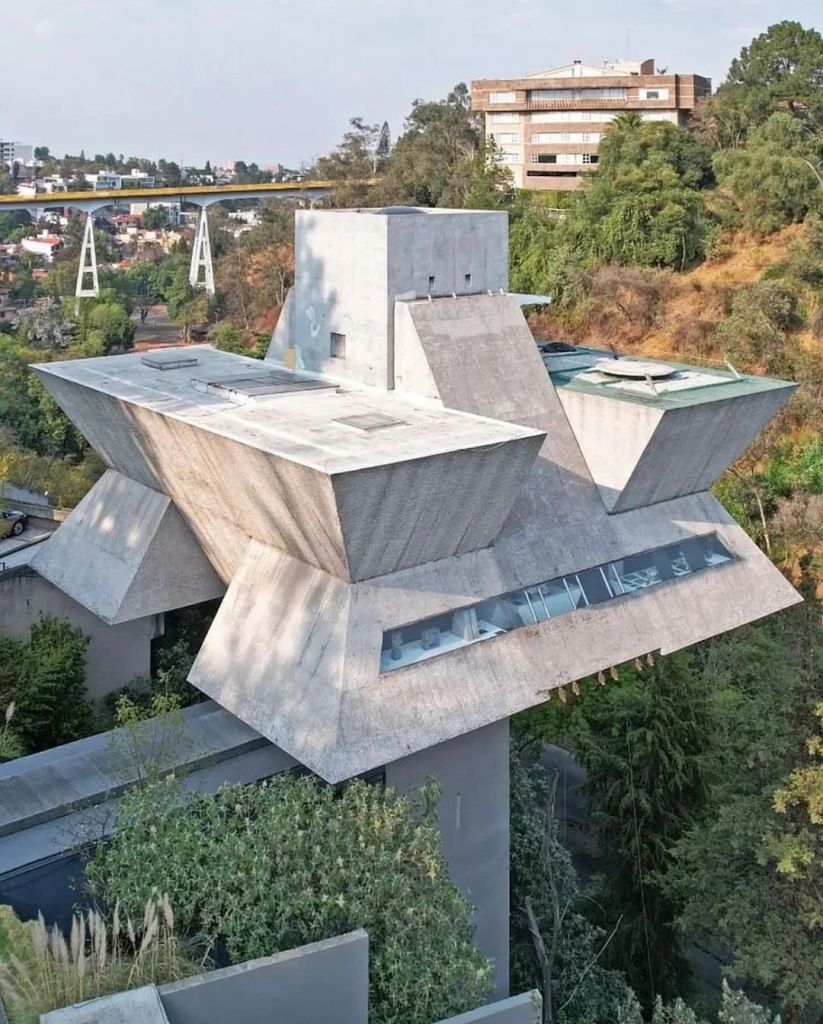

Praxis house located at Bosque de Acacias 61, Bosque de las Lomas, Miguel Hidalgo, 11700 Ciudad de México was designed by the architect Agustín Hernández Navarro in 1975 and was his home and studio.

Mexican architect and sculptor Agustín Hernández Navarro pioneered an idiosyncratic approach to 20th century Modernism. His futuristic forms are inextricably woven with references drawn from Mexico’s history – via structures and relics of the Mayan, Aztec and Zapotec periods.

A living monument to his architectural philosophy, his Brutalist home-studio Praxis House stands on the outer edge of Mexico City, a sculptural concrete landmark levitating among the treetops of the Bosques de la Lomas.

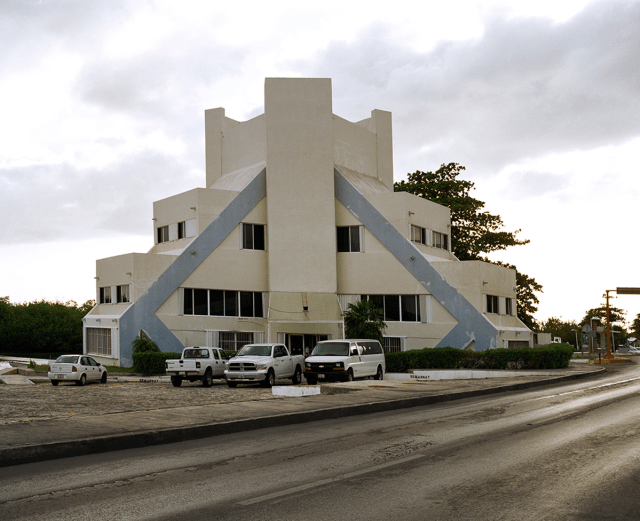

Escuela de Ballet Folklórico de México

Another of Agustíns works is the 1968 escuela de ballet folklórico de méxico inspired by the “aesthetic of Mayan pyramids”

The Folkloric Ballet School was founded by Agustín Hernández Navarro’s choreographer sister Amalia Hernández and constructed in the Colony Guerrero, Mexico City. The structure which houses two rehearsal rooms, an office and a theatre, references the slope of a Pre-Colombian pyramid base while asserting itself as a modern piece of architecture

Agustín built artistic and mind boggling homes such as this one, the Casa en el aire (1991)

La Casa en el Aire or The House in the Air is a gravity defying structure located in the Bosques de las Lomas area of Mexico City. With the main hall built at a 45 degree tilt that is suspended in air, the building makes use of the surrounding steep terrain by veiling the garages and service areas with the surrounding slope. The structure is constructed with concrete slabs and steel cantilevers which mimic a levitated snake like shape. With this project, Hernández Navarro sought to merge the space of the edifice with the air rather than with the soil of the Earth

More mundane but no less spectacular family homes

House with pre-Hispanic inspired motifs from Oaxaca in Colonia Chapultepec,

Architect Ludwig Godefroy

2015 – Zicatal (Oaxaca) The house is a bunker on the outside protecting a Mexican pyramid on the inside,”

Zicatela House is a small weekend house located on top of a hill in front of Zicatela beach, next to Puerto Escondido in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico.

Casa Merida (2018)

Architect Ludwig Godefroy has designed this fragmented concrete house, which spans an 80-metre-long site in Mérida, Mexico, to draw on Mayan traditions and culture.

The Mexico City architect completed the house in Mérida, the largest city in Yucatán state. Casa Merida is a single-family house project located in the historic centre of Mérida, a few blocks away from its main central square, in its colonial area.

Urban spaces

Pablo Lopez Luz (born 1979 in Mexico) is a photographic artist living in Mexico City.

Pablo’s exposition “Pyramid” was born out of questioning two core concepts: history and the role the pyramid performs in the contemporary world, as well as the joint creation of the notion of identity.

Throughout history, the Mexican population has been victimised by the superposition of different historic layers and cultural impositions, culminating in the creation of a hybrid society that persistently struggles to define its own identity

The emergence of neo-pre-Hispanic architecture in government buildings and national monuments during the first half of the 20th century obeyed the ideological need among the ruling class to strengthen a Mexican sense of nationalism.

Belén Moneo, Jeffrey Brock Parish Church in Pueblo Serena Monterrey, Nuevo León

Maria Montessori Mazatlán School (2016)

The Maria Montessori School of Mazatlán designed by architects EPArquitectos, Estudio Macías Peredo, Salvador Macías Corona, Magui Peredo Arenas, Erick Pérez Páez is a field of uniquely reoccurring forms and layers, creating its own urban fabric and community. Beyond this, it exists as a successful series of well-designed spaces fit for the climate (high heat, humidity and salinity) Rather than designing the building as a whole, they imagined a cell – the classroom – and established rules for this to form, in turn, the field for the school as a micro-city. Made from an array of small geometric modules with only a single front to the wider city, and in the absence of an adjacent urban fabric, it weaves its own plazas, streets, patios, and sanctuaries into a truly unique self-contained city-state.

Rebuilding with intent

In October 2018, Hurricane Wilma caused great damage and flooding along the coasts of Sinaloa and Nayarit, affecting multiple municipalities, including the municipality of Tecuala. an Urban Improvement program was initiated to rebuild public spaces destroyed by the hurricane.

Plaza Monumento a la Madre

The plaza has been designed in an open manner like many prehispanic public spaces and with a structure that evokes stepped pyramids.

This is but a small taste of the ongoing creation of México through architecture fuelled by a prehispanic dreaming.

References

- Austin AL, Luján LL, Sugiyama S. The Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacan: Its Possible Ideological Significance. Ancient Mesoamerica. 1991;2(1):93-105. doi:10.1017/S0956536100000419

- Coronel, Juan (2007). Diego Rivera Coleccionista. Mexico, 2007.

- De Anda Alanís, Enrique X. (2004). «Frontons». Central Campus of Ciudad Universitaria, Visitor’s Guide (in Spanish, French and English) . Mexico: National Autonomous University of Mexico. p. 74-75. ISBN 978-607-02-2538-3 .

- Gómez Porter, Pablo Francisco. (2020). Read Alberto T. Arai. Reflections, essays and texts. Cuicuilco. Journal of Anthropological Sciences , 27 (77), 259-264. Epub March 24, 2021. Retrieved on May 29, 2024, from http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2448-84882020000100259&lng=es&tlng=es.

- Kifuri Rosas, Yurik (February 8, 2011).«The pediments of Ciudad Universitaria».Architecture Log 0(11): 48-51-51. ISSN 2594-0856 . doi : 10.22201/fa.14058901p.2004.11.26364 . Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo, Mexico at the World’s Fairs: Crafting a Modern Nation. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1996, p. 64.

- Ortíz, Guillermo; et al. El Anahuacalli de Diego (México: Banco de México, 2008

- Pellicer, Carlos. Anahuac-calli. Revista Artes de México. Número 64/65, Año XII, 1965

- “Rendirán homenaje al autor del Monumento de la Plaza de la Paz – Guanajuato Capital”. http://www.guanajuatocapital.gob.mx. Presidencia Municipal Guanajuato. Retrieved 5th June 2024.

Website Links

- https://www.nzz.ch/english/architecture-in-mexico-takes-an-overdue-turn-toward-public-space-ld.1652157

- https://www.boredpanda.com/i-took-pictures-of-the-masterpieces-of-some-mexican-architects/

- https://www.c41magazine.com/pablo-lopez-luz-pyramid/

- https://archeyes.com/parish-church-pueblo-serena/

- https://www.iancampophoto.com/blog/mexican-brutalism-mexico-city-brutalist-architecture

- https://adip.info/2012/09/mosaic-murals-of-the-unam-central-library/

- https://realestatemarket.com.mx/arte/20150-bellas-artes-la-historia-de-la-construccion-del-icono-del-arte-en-mexico

- https://www.nowness.com/series/constructed-views/praxis-agustin-hernandez-navarro

- https://www.facebook.com/wearchitectsdz

- https://www.facebook.com/museoanahuacalli

- https://museoanahuacalli.org.mx/

- https://mexicocity.cdmx.gob.mx/venues/anahuacalli-museum/?lang=es

- Anahuacalli terrace – By Tamara Toledo – Cortesía del Museo Diego Rivera-Anahuacalli. https://museoanahuacalli.org.mx/, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116892219

- Diegos Ofrenda – https://newlydevary.com/2019/01/04/diego-rivera-anahuacalli-museum/

- Roof terrace – By AlejandroLinaresGarcia – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10197072

- Diego Rivera on the steps of a Maya portal, inside the Anahuacalli – By Archivo Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo, Banco de México, Fiduciario en el Fideicomiso relativo a los Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo. – Archivo Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo, Banco de México, Fiduciario en el Fideicomiso relativo a los Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo. https://museoanahuacalli.org.mx/, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116866718

- Diego Rivera during the construction of the Anahuacalli – By Archivo Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo, Banco de México, Fiduciario en el Fideicomiso relativo a los Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo. – Archivo Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo, Banco de México, Fiduciario en el Fideicomiso relativo a los Museos Diego Rivera y Frida Kahlo. https://museoanahuacalli.org.mx/, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116866719