Architecture in the Americas and places much further afield such as Australia has been affected by the building styles of wealthy land owning Spaniards and their time colonising Mexico. After the initial invasion and the creation of centrally located cities built from the stones of dismantled pyramids and other local Mexican architecture the Spaniards ventured further afield in their depredations. In the process they began to build from locally sourced materials in styles familiar to their homeland. Aside from a plethora of churches they built many semi fortified structures (churches were also included in this as well) to protect themselves and their newly acquired properties and industries. This all began with the haciendas.

Haciendas

Haciendas are a result of the encomienda system enforced by the Spanish crown.

As legally defined in 1503, an encomienda (from Spanish encomendar, “to entrust”) consisted of a royal grant of land (and later a repartimiento – which essentially had the same effects) by authority of the crown, Queen Isabella I of Spain, to a conquistador, a soldier, an official, or various others (including priests) over a specified number of “Indios” (in this case Mexicans and, later, Filipinos) living in that particular area. This power was usually awarded in recognition of special services to the crown. For example, as recognition for his conquest of the Aztec Empire, conquistador Hernán Cortés was awarded an encomienda territory that included 115,000 Indigenous inhabitants.

The receiver of the grant, the encomendero, was granted the “legal right” to exact tribute from the “Indios” in gold, or most often in forced labour and the encomendero was in return required to protect them and instruct them in the Christian faith.

The encomienda system was not considered slavery since the labourers could not be bought and sold to a third party. In practical terms, though, there was little difference and labourers could be and were sold.

The cruelties of the encomienda and its enslavement systems fell particularly hard on women. This hardship also created two words quite unique to the Mexican language; mestizo/mestizaje (of mixed race) and chingar (colloquially the equivalent of “fuck” but with a more violent undertone). Professor Jaques Lafaye (1) and Octavio Paz have written on the creation of these terms as they relate to the psyche of the Mexican people and I feel it important you know a little of these terms and that they relate directly to indigenous Americans as they stem from the abuses of the encomienda system. Lafaye notes that the mestizo characterize themselves in a self abasing tone as the “hijos de la chingada, fruits of the violation of Indian women by Europeans” and Paz explains in his essay Sons of La Malinche that the verb chingar is replete with meaning and that its essential meaning is rooted in physical aggression: “The verb denotes violence, an emergence from oneself to penetrate another by force. It also means to injure, to lacerate to violate-bodies, souls, objects-and to destroy.” La chingada, then, “is the Mother forcibly opened, violated or deceived.” She is the raped “Indian” mother of us all who is associated with the Conquest, “which was also a violation, not only in the historical sense but also in the very flesh of Indian women”

- a French historian who, from the early 1960s has written influentially on cultural and religious Spanish and Latin American history. His most popular work is “Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe” written in 1974 regarding the formation of the Mexican National Consciousness which includes a prologue by Octavio Paz. The book is regarded as a keystone for the understanding of the contemporary Mexican culture and is regarded as one of the most comprehensive analyses of the colonial period in Mexico.

- An influential Mexican poet and author

Originating in the colonial period, the hacienda survived in many places late into the 20th century. Scholars argue that this system did not evolve from the encomienda system but there is little that differentiates the two. The labourers, typically native americans, who worked for hacendados (landowners) were theoretically free wage earners, but in practice their employers were able to bind them to the land, especially by keeping them in an indebted state and by the 19th century it has been approximated that up to a half of the rural population of Mexico was thus entangled in this system of peonage (1).

- peonage (the word itself etymologically stems from the Americas and the abuses of the indigenous peoples of the Americas by the Spanish) – a form of involuntary servitude, the origins of which have been traced as far back as the Spanish conquest of Mexico, when the conquerors were able to force the poor, especially the Indians, to work for Spanish planters and mine operators.

The term hacienda is imprecise, but usually refers to landed estates of significant size, while smaller holdings were termed estancias or ranchos. All colonial haciendas were owned almost exclusively by Spaniards and criollos (1). A lot of haciendas were used as mines, factories, or plantations, and some combined all of these activities.

- In Hispanic America, criollo is a term used originally to describe people of full Spanish descent born in the viceroyalties (Spanish owned territories ie. in the New World, in this case Mexico). In the context of the Spanish Empire, a peninsulare was a Spaniard born in Spain residing in the New World (and was someone who considered themselves culturally superior to a criollo)

Haciendas of Yucatán were agricultural organizations that emerged primarily in the 18th century. They had a late onset in Yucatán compared with the rest of Mexico because of geographical, ecological and economical reasons, particularly the poor quality of the soil and lack of water to irrigate farms. Commonly the farms were initially used exclusively for cattle ranching, with a low density of labour, becoming over time maize-growing estates in the north and sugar plantations in the south, before finally becoming henequen estates

Although Hacienda architecture is original to Spain and Mexico, where it’s considered a traditional architectural style with traditional building techniques, hacienda-style homes have a long history in the United States. Between the 1600s and mid-1800s, Spanish settlers built their hacienda homesteads in states like California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Florida, because they shared warmer, drier climates similar to their homelands.

From the Hacienda to the Mission. Gods work continues.

Spanish missions were institutions established by Catholic religious orders under the auspices of the Spanish crown during the 1500s to the 1800s. The Spanish wanted to take over the land, and the missionaries were part of that plan. They wanted to spread their religion of Roman Catholicism to the Indigenous peoples who lived on the land. The missions were also set up in part as the abuses of the indigenous peoples suffered under the encomienda system were not being taken lightly by the Church. The Church did not really do any better than the conquistadors and was itself guilty of many abuses against the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

In 2019, Mexico’s newly-elected populist president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (also known as AMLO), sent an open letter addressed to Pope Francis and to King Felipe VI of Spain. In the letter, he asked for the recipients to apologise for the crimes committed against the Indigenous population of Mexico during the Spanish conquest.

In 2021, as part of the bicentennial celebrations of Mexico’s 1821 independence from Spain AMLO offered an official apology to the indigenous Maya peoples for the “terrible abuses” committed against them in the centuries since the Spanish conquest. AMLO specifically singled out the 1847-1901 Caste War, an Indigenous rebellion in which some 250,000 people are believed to have died. The Caste War of Yucatán began with the revolt of native Maya people of the Yucatán Peninsula against Hispanic populations, called Yucatecos who had long held political and economic control of the region. It was reported however that “jeering was heard during the ceremony from residents who oppose the construction of Lopez Obrador’s “Maya Train” pet project to link Caribbean resorts with ancient archaeological sites.”

This project, although being said to bring economic growth to the area, is proving to be highly problematic.

The construction has been a boon to the study of archaeology on the peninsula with more than 58,000 fixed elements, such as structures and foundations having been uncovered as well as, over 1.4 million pottery shards, nearly 2,000 furniture objects, including pieces of great historical value, and (so far) 669 human remains have been unearthed.

Indigenous peoples living in the area are being displaced, as many as 3000 households so far, thousands of acres of jungle are being demolished to make way for the train, and cenotes (1) in particular are being destroyed. Although massive amounts of archaeological finds are being made the environmental destruction of the area is huge.

- A Cenote refers to an underground chamber or cave which contains permanent water. They are natural sinkholes where the ceiling of the cave has collapsed and are important sources of fresh water in an otherwise very arid climate. The word Cenote is a Spanish conversion of the Yucatec Maya word “D’zonot” or “Ts’onot”. So far 2,252 natural features such as caves and cenotes have been catalogued during the clearing of the forest.

In the rush to complete the railway before AMLO’s term ends in 2024, construction began before studies of its environmental impact were completed.

Protests against the construction have also been hindered somewhat via another controversy which arose when AMLO put the construction and operation of the Tren Maya under military control.

It seems that self determination and autonomy of the indigenous people is still reliant upon the wishes of the government.

The Spanish Missions

The Spanish missions in California formed a series of 21 religious outposts or missions established between 1769 and 1833 in what is now the U.S. state of California

In Texas the first Spanish missions were established in the 1680s near present-day San Angelo, El Paso and Presidio – areas that were closely tied to settlements in what is today New Mexico. In 1690, Spanish missions spread to East Texas after news surfaced of La Salle’s (1) French settlements in the area.

- René-Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle (born November 22, 1643, Rouen, France—died March 19, 1687, near Brazos River [now in Texas, U.S.]) was a French explorer in North America who led an expedition down the Illinois and Mississippi rivers and claimed all the region watered by the Mississippi and its tributaries for Louis XIV of France, naming the region “Louisiana.”

The municipal seat was formed in the year 1688 as Mission La Purísima Concepción de Nuestra Señora de Caborca, by the Jesuit missionary Francisco Eusebio Kino on the point called Caborca Viejo (Old Caborca). In 1790, it was established on the site that it currently occupies, on the right (east) bank of the Asunción River.

Mission San Antonio Paduano de Oquitoa was founded in 1689 by the Jesuit missionary Eusebio Kino. One theory is that the name Oquitoa means “white woman” in the Piman language.

Father Kino was at San Ignacio in 1687, the day after he had first arrived at Dolores. He described Cabórica as a “very good post . . . inhabited by affable people”—as it continues to be. It was three years before a missionary was stationed here and three more years before anyone was permanently assigned. Whatever church may have existed before 1693 when Father Agustín de Campos began his incredible forty-two-year tenure at San Ignacio is likely to have been no more than a ramada (branch).

Mission San Pedro y San Pablo del Tubutama is a Spanish mission located in Tubutama, Sonora, first founded in 1691 by Eusebio Francisco Kino

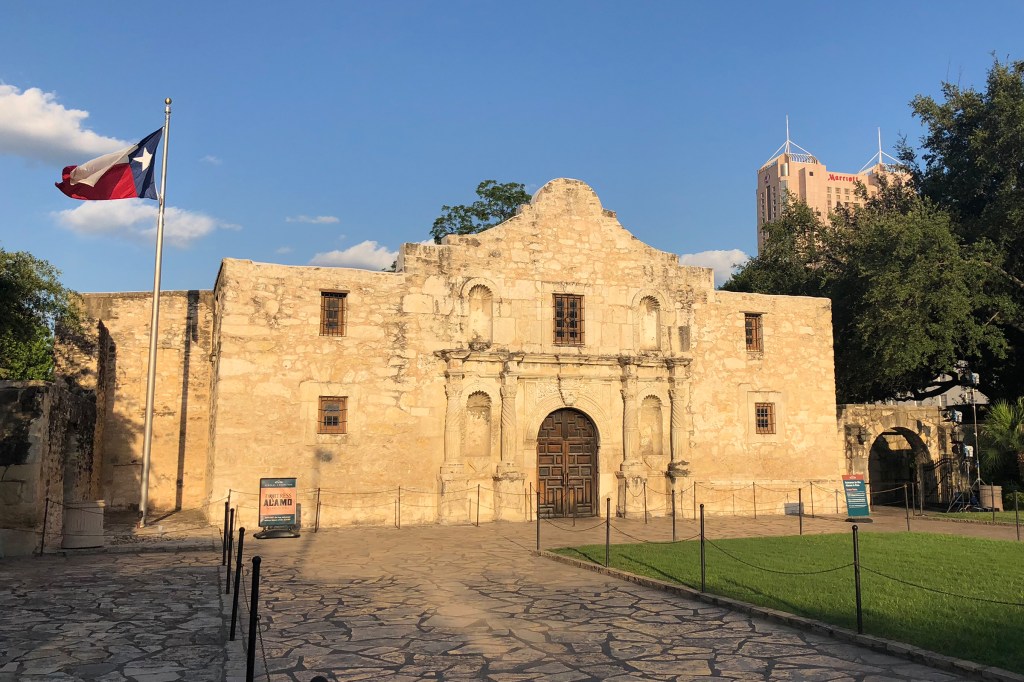

The Alamo is a historic Spanish mission and fortress compound founded in the 18th century by Roman Catholic missionaries in what is now San Antonio, Texas, United States. While the Alamo may be the most well-known of these missions, Spanish priests established five additional Catholic missions: San Antonio de Valero, San José, Concepción, San Juan and Espada, all along the San Antonio River.

The New Mutants: Dead Souls #1 (No More Heroes)

The building was originally the chapel of the Mission San Antonio de Valero, which had been founded between 1716 and 1718 by Franciscans. Before the end of the century, the mission had been abandoned and the buildings fell into partial ruin. After 1801 the chapel was occupied sporadically by Spanish troops. Apparently, it was during that period that the old chapel became popularly known as “the Alamo” because of the grove of cottonwood trees in which it stood.

In December 1835, at the opening of the Texas Revolution (War of Texas Independence), a detachment of Texan volunteers, many of whom were recent arrivals from the United States, drove a Mexican force from San Antonio and occupied the Alamo.

On February 23, 1836, a Mexican army, variously estimated at 1,800–6,000 men and commanded by Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna, arrived from south of the Rio Grande and immediately began a siege of the Alamo.

On the morning of March 6 the Mexicans stormed through a breach in the outer wall of the courtyard and overwhelmed the Texan forces. Santa Anna had ordered that no prisoners be taken, and virtually all the defenders were slain (only about 15 persons, mostly women and children, were spared). The Mexicans suffered heavy casualties as well; credible reports suggest between 600 and 1,600 were killed and perhaps 300 were wounded.

The Death of the Missions

These Missions were largely abandoned in the 19th Century as they began receiving less aid from the Spanish government and few Spanish were willing to become mission priests. In increasing numbers Indians deserted and mission buildings fell into disrepair. Mexican independence led to the final demise of California’s mission system.

Their style did not die out though

The Spanish Colonial-style home is considered a classic architectural style found throughout Florida, California, and Southwestern states, like Arizona and New Mexico. Although Spanish Colonial homes have an even longer history in Spain and Mexico, they first appeared in North America between the 1600s and mid-1800s, when Spanish settlers arrived and began building their homesteads.

Mission Revival drew inspiration from the late 18th and early 19th century Spanish missions in California.

California, in search of an architectural identity for itself, starts to look to its Mexican past, fusing elements of colonial design into early Modern structures: white stucco, red-tile roofs, arched openings and iron-grille windows.

Known for their white stucco walls, red clay roof tiles, and rustic appearance, Spanish Colonial homes are popular throughout the Southeastern and Southwestern sections of the United States, including Florida and California. Long before this style came to North America, however, it had a long, varied history in both Spain and Mexico.

Attributes and features of the California Mission revival style

- Red clay roof tiles

- Smooth, white stucco walls

- Wide, overhanging eaves

- Mission-shaped roof parapet or dormers

- Porches and breezeways supported by columns or exposed wooden beams

- Arched doorways

- Deep window openings without framing

Originating in California, the Mission Revival architecture style pays homage to the Hispanic history and heritage of the Golden State. Used by hotels and train depots originally, the style became popular amongst residential developers as a way to complement the vast landscapes and invoke a romanticized feeling of the lost Spanish past.

Inspired by the Franciscan missions, this style became a favorite for East Coast settlers in the late 19th century. With their characteristic stucco walls, low-pitched red clay roofs, and prominent arches, these homes are abundant in neighborhoods from Highland Park to Hollywood Hills. Los Angeles’ distinctive Mission Revival architectural style, a nod to the Franciscan Alta California missions, are iconic structures easily recognized by their red clay tile roofs, plain stucco exteriors, and graceful arches complemented by mission-style parapets.

By naming the style Spanish Colonial Revival, it had the effect of erasing Mexican influence from the architecture of California.

Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne noted in his review of “Found in Translation.”

“When Myron Hunt and George Washington Smith produced their most ambitious Spanish Colonial designs between 1900 and 1930, they weren’t just gazing back to Southern California’s Spanish and Mexican pasts; they were pointedly giving a foothold to a respectable Eurocentricism here,” he wrote. “It was commonplace to ‘misidentify’ Mexican artifacts as Spanish … precisely because of this preference for a European lineage over a pan-American one.”

The style soon found its way back to México.

During the early 20th century, Mexican design was also in the process of revisiting its colonial architecture — albeit as a tool for building national identity in the wake of the Mexican Revolution. Spanish Colonial Revival, however, took many liberties with these historic forms.

Even though Colonial Californiano was commercially popular in its heyday in the early 20th century, it was almost universally reviled by Mexican scholars and avant-garde architects.

“They hated it because people thought it was Mexican,” says Cristina López Uribe, a member of the architecture faculty at Mexico’s National Autonomous University. “But it was really a copy of Spanish Revival” — which hailed from the United States.

Mexican Modernist Luis Barragán noted the absurdity of the situation at a California architectural event in 1951.

“In Mexico we have had the misfortune of the influence of California Colonial … the use of which in our country is so absurd, since this style was brought to Mexico, and from Mexico to California,” he stated dryly. “Los Angeles and Hollywood then exported it once again to Mexico as California’s Spanish Colonial.”

in Mexico City you can see constructions with this trend in neighbourhoods such as Hipódromo, Anzures, Polanco, Condesa, Nápoles, Lomas de Chapultepec, Merced Balbuena, Álamos and Del Valle, among other neighbourhoods that had their greatest development towards the middle of the 20th century.

Colonia Anzures

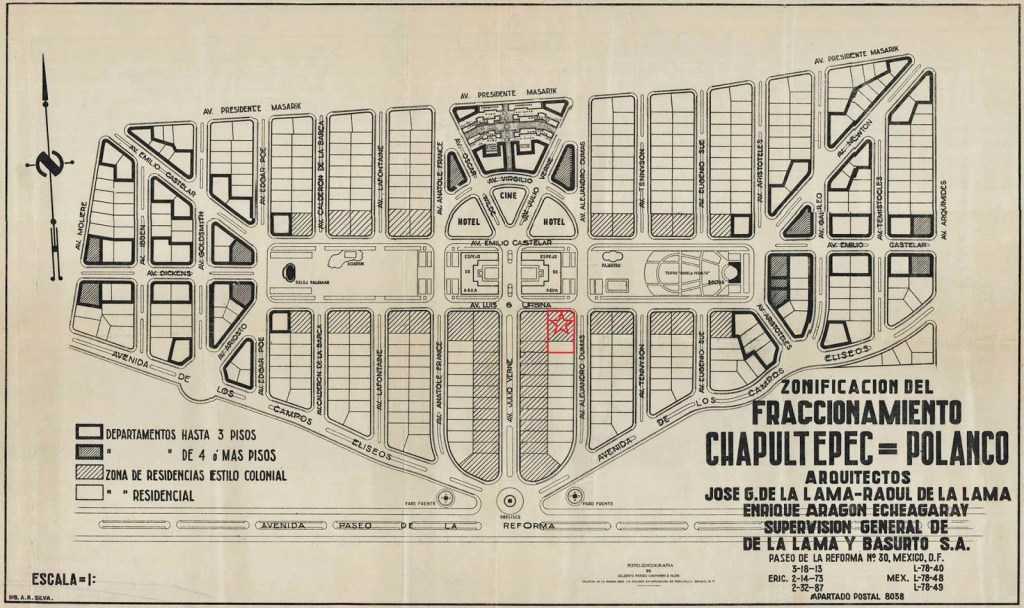

Polanco

La casa de don Elías Henaine

Built in 1938 – following the design of Eduardo Fuhrken Meneses – and belonged to Don Elías Henaine, an immigrant of Lebanese origin who arrived in Mexico in 1898 and made his fortune in the sale of National Lottery tickets.

In correlation with the success of his businesses, Elías Henaine had moved his residence to the streets of Independencia first and Versalles later, but by the end of the 1930s, he became interested in the new subdivision called “Chapultepec-Polanco.

Pasaje Polanco was conceived as part of the urbanization project for the Polanco area at the end of the 1930s.

In the expensive and fashionable Mexico City district of Polanco, architect Francisco J. Serrano, who had a close connection to Los Angeles (he frequently traveled to the city to buy films for a cinema he owned) designed the undulating Pasaje Polanco, a mixed-use apartment complex completed in 1939. The Modern design bears Spanish Colonial Revival elements such as red-tile roofs, arched passageways and bright ceramic tile details.

The promotional plan of the original subdivision,

Pasaje Polanco, originally Pasaje Comercial, is an architecturally significant open-air shopping court with apartments on the upper levels along Avenida Masaryk in the Polanquito section of the Polanco neighborhood of Mexico City. It is in Colonial californiano style, that is, a Mexican interpretation of the California interpretation of Spanish Colonial Revival architecture and Mission Revival architecture.

Benito Juarez

Colonia Nápoles is a colonia in Benito Juárez, Mexico City in the North central area of the metropolis. Along with Colonia Del Valle, it’s among the most representative of Mid-Century neighbourhoods of Mexico City.

Spanish Mission Revival Architecture in Australia

On the 1st of March 1847 the foundation stone of the New Norcia Benedictine monastery in Western Australia was laid. The abbey was founded by two Spanish Benedictine monks, Giuseppe Serra and Rosendo Salvado. Much like the missions in the Americas it was built with the purpose of disseminating Catholicism to the aboriginal peoples of the area.

Rosendo Salvado, 12 March 1867 – 29 December 1900, died as abbot, aged 86 years

The Mission Revival style was part of an architectural movement, beginning in the late 19th century, for the revival and reinterpretation of American colonial styles. Mission Revival drew inspiration from the late 18th and early 19th century Spanish missions in California. It is sometimes termed California Mission Revival.

In 2015 the Perth chapter of FOMEX visited New Norcia to visit their Virgen de Guadalupe and sing “Las Mañanitas” to the Virgin, and do la posada “Mexican style”.

In Australia, the style is known as Spanish Mission. Australia’s Spanish Mission-style houses are a more modern preference. A renewed interest in their design sprung up in the early 20th century. This revival was spurred by interest in Hollywood movie stars, who had taken to living in luxurious Mission mansions.

The popularity of this ‘Spanish Mission’ style owed a great deal to Professor Leslie Wilkinson after he was appointed the first Professor of Architecture in any Australian University in 1919.

One of the best examples of Spanish mission is Biscaya, at 27 Victoria Road Bellevue Hill in Sydney, New South wales. Built in the 1930s by architect F. Glen Gilling, the home was a consular residence for many years

References

- Binding, N., & Binding, R. (2008). Haciendas and Hollywood Spanish mission style. Spirit of Progress, 9(1), 18–21. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.717714603063552

- The Historical Background of the Australian ‘Spanish Mission’ Style Bungalows, and the Case for Preservation. (1998). Architectural Science Review, 41(2), 49–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00038628.1998.9697408

- Lacey, Stephen (2007-11-01). “Spanish mission style”. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2022-09-25.

- Lafaye, Jacques. 1974. Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness 1531 – 1819. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- MISSION STYLE IN ARCHITECTURE. (1925, July 30). The Register (Adelaide, SA : 1901 – 1929), p. 4. Retrieved May 29, 2024, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article57300109

- Paz, Octavio. 1985. The Labyrinth of Solitude: And Other Writings. New York: Grove Weidenfeld.

- Steinberger, Staci, Megan E. O’Neil, Bobbye Tigerman, Abbey Chamberlain Brach, Ellen Dooley, Clarissa M. Esguerra, Miranda Saylor, Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA (Project), and Los Angeles County Museum of Art. 2017. Found in Translation : Design in California and Mexico, 1915-1985. edited by W. Kaplan. Los Angeles, California, Munich, Germany: Los Angeles County Museum of Art ; DelMonico Books/Prestel.

- https://grandescasasdemexico.blogspot.com/2017/03/la-casa-de-don-elias-henaine-en-polanco.html

- https://fomexwa.blogspot.com/

- Tren Maya Archaeological Discoveries – https://trenmayaa.com/en/news/shocking-archaeological-finds-on-the-mayan-train-route/ : https://www.vallartadaily.com/thousands-of-archaeological-sites-found-on-mexicos-mayan-train-route/ : https://www.heritagedaily.com/2023/06/deity-of-death-statue-found-during-maya-train-construction/147702#google_vignette

- Tren Maya : Cenotes Catalogued – https://trenmayaa.com/en/news/shocking-archaeological-finds-on-the-mayan-train-route/

- Tren Maya Destruction – https://news.mongabay.com/2023/09/mexico-groups-say-maya-train-construction-has-caused-significant-deforestation/

- Tren Maya Protests – https://schoolsforchiapas.org/the-socio-cultural-impacts-of-the-tren-maya/ : https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/may/23/fury-as-maya-train-nears-completion-mexico