This Post is the 4th in a series resulting from a presentation I made at the WA Museum in Perth Western Australia as one of a series of talks presented by the Friends of Mexico (FOMEX) in W.A. My original talk was only a brief one as I was only allotted 60 minutes for my presentation which, once I started researching the subject, I realised was woefully inadequate for the task at hand. The subject of architecture in Mexico could fill ones life many times over with the amount of research that would be needed on the subject (as could researching the architects themselves). Below is presented in greater detail one of the previously unknown to me aspects of architecture and social structures of México City in particular (a city I am deeply in love with).

For more info on my original talk see……

This is Mexico : Building a Country : The Architecture of Mexico : Part 1

and for the other subjects I expanded upon please visit…….

This is Mexico : Building a Country : The Architecture of Mexico : Part 2 : Prehispanic Inspiration. and

This is Mexico : Building a Country : The Architecture of Mexico : Part 3 : Colonial Californiano

Mexico City’s Vecindades and How They Became Homes for the Working Class

Vecindad (= barrio) in the context of this Post; vecindad = neighbourhood; and in Mexico; vecindad = a kind of tenement where individual apartments encircle a central patio, and residents often share facilities such as bathrooms and kitchens.

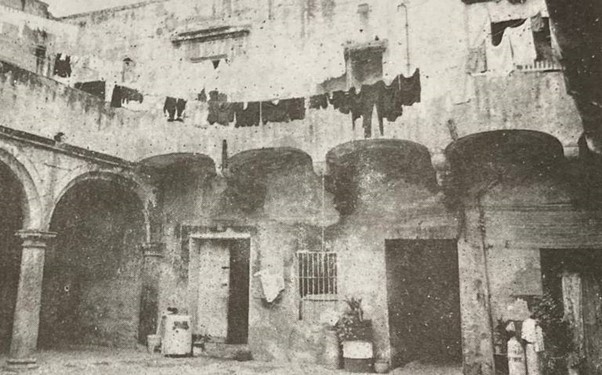

Originally inhabited by European aristocracy these buildings became tenements (1) for the poor working classes and their courtyards became hubs of communal activity and the beating heart of communities.

- A tenement is a type of building shared by multiple dwellings, typically with flats or apartments on each floor and with shared entrance stairway access

Photographer: Alejandro Cegarra/Bloomberg

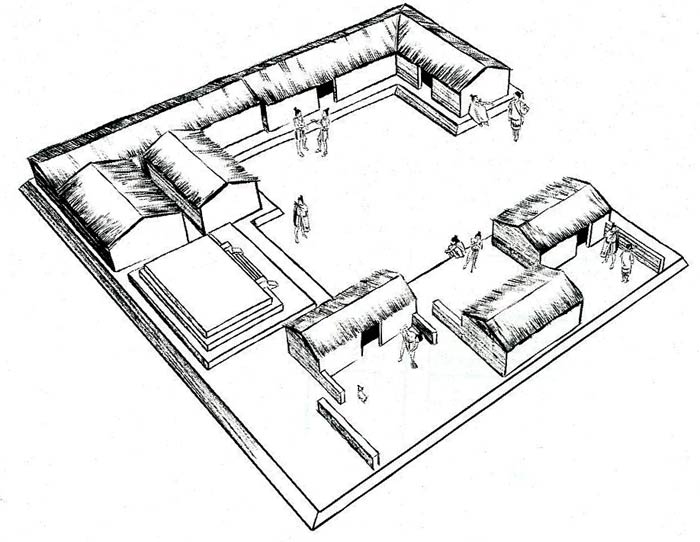

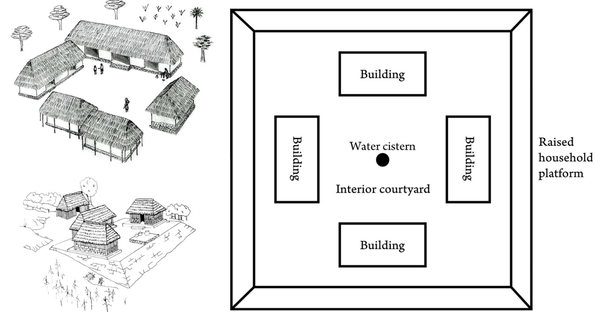

History shows that Mexican domestic, indigenous architecture had similar characteristics to those existing in the Islamic and Andalusian houses. In Teotihuacan archaeological surveys show that residential buildings consisted of rooms, porticos and corridors surrounding several patios.

Much like the forthcoming vecindades the arrangement of these semi-private open spaces and patios demostrated the existence of a collective life.

In Tenochtitlan the basic collective dwelling was fairly large, approximately 500 m2, containing five or six family dwellings which were one or two stories high each of which opened on to an open space or patio. Each dwelling was formed of one or two rooms with an area between 10 to 30 square meters. A well and collective bathrooms were placed next to the family dwellings.

The history of communal living structures in Mexico City is rich and deep and these buildings tell a story about the city’s development into the megalopolis (1) it is now.

- A megalopolis (or a supercity) also called a megaregion, is a group of metropolitan areas which are perceived as a continuous urban area through common systems of transport, economy, resources, and ecology. They are integrated enough that coordinating policy is valuable, although the constituent metropolises keep their individual identities. This also rang true for the altepetls of Tenochtitlan.

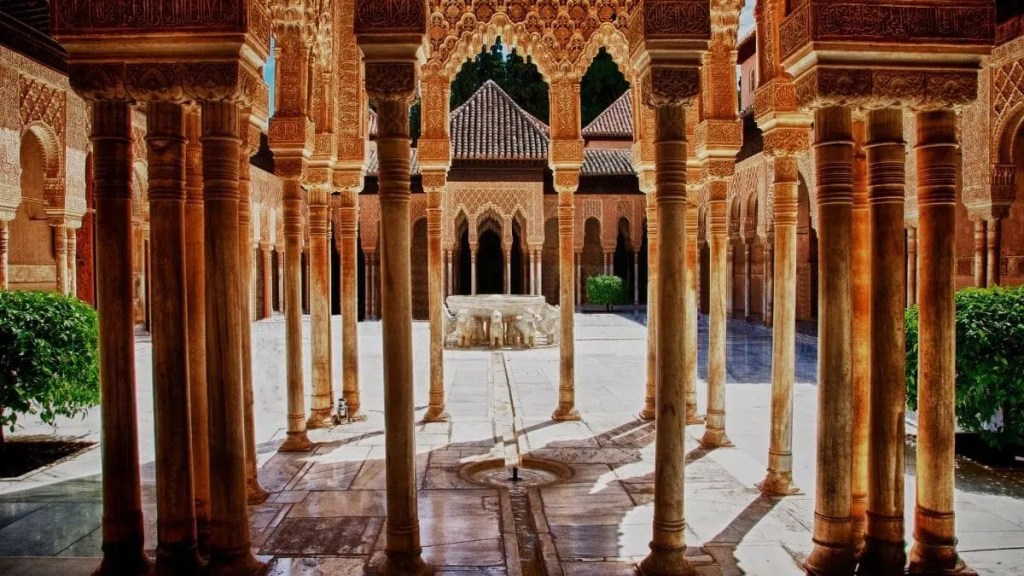

The buildings that would eventually become vecindades began to be constructed in Mexico City’s historic center in the 16th century, right after the arrival of Spanish colonists. During Spanish rule, wealthy families built large homes in a classic Andalusian Spanish style, with rooms spanning multiple stories encircling an open-air patio — a descendant of the Roman Atrium that may have remained popular in Spain due to the influence of Islamic architectural traditions, which favor inner courtyards. This structure kept the space cool, encouraging airflow between rooms in the home

Originally constructed as grandiose Spanish constructions many central located vecindades were originally grand housing built solely for the elite.

Were these colonial mansions built using witchcraft?

Now this is an interesting story (and one that I’m seeking more source material one) but it has been said that (maybe) dark magic was used to build some of these colonial casonas (large houses/mansions) and palaces in the heart of the city in what was only a short time ago the city of Tenochtitlan. An (in)famous alarife (1) by the name of Jaramilllo was bought in from Spain to construct the first mansions of the colonial period for the the conquistadors in New Spain. He offered his clients buildings that would not be affected by the tremors and earthquakes prevalent in the area. His terms included that he would only build at night. His assistants bought babies which had been either “purchased” or kidnapped from the native women of Tlaxpana and, along with nubile maidens (núbiles doncellas) they were walled up into niches, arches and in specially prepared spaces in the corners of the walls whilst still alive. It has been said that between 30 and 40 victims were immured (2) into each wall. The dark magic arises in that living victims (rather than dead bodies alone) were required as the constructive principle relied on the anguish, terror and panic of the victims because the discharge of energy released by this anguish merged with the buildings architecture and gave it supernatural strength. The dead were not entombed for this very reason. This dark secret is said to be the reason why some of these buildings have prevailed during both flood and earthquake since then. I have found anecdotal reference to remains of these bodies being found during electrical installations of vecindades along the Correo Mayor in the CDMX but have yet to find any real evidence of this (I am looking though)

- Alarife (from Hispanic Arabic العَرِيف «alʿaríf», in turn from Classical Arabic عريف «ʿarīf», expert and alarifazgo are terms in disuse that designated the master of Mudejar masonry in the Iberian Peninsula. Among the trades related to construction it was synonymous with the architect or the master builder/mason and in general with the bricklayer (albañil)

- Entombed while still alive

Tlaxpana is a colonia in the Delegación Miguel Hidalgo in El D.F.

In its day it was famous for the Fuente de la Tlaxpana (Fountain of Tlaxpana) and the aqueduct which carried fresh water into México City.

These colonial buildings that would soon become vecindades and their architectural layout do remind me somewhat of multi-storey haciendas.

These buildings, usually between two and five stories high, had windows facing inward toward an elongated patio. They tended to be on very narrow lots, about 10 meters wide, and made of compact stone or brick. The rooms themselves also tended to be narrow, around 3 square metres, albeit with high ceilings which acted as a passive cooling technique. While some of these courtyard mansions were plain, many had stone facades and intricate stonework or other decorative elements, including portraits depicting old Spanish families or religious figures — all denoting their owners’ wealth. This model continued into the late 18th century, from which many vecindades date.

All of these properties had a very similar architectural design. They had robust facades and gates that gave access to the centre of the construction where there was a large central patio with a fountain and the rooms around it, which lent themselves very well to being adapted into multifamily homes.

Being colonial buildings, these high ceilings of the bedrooms at some point had plugs added to allow the addition of mezzanines. “The phenomenon of mezzanines was an architectural solution that was developed to take advantage of the space between one floor and another.”

Photographer: Alejandro Cegarra/Bloomberg

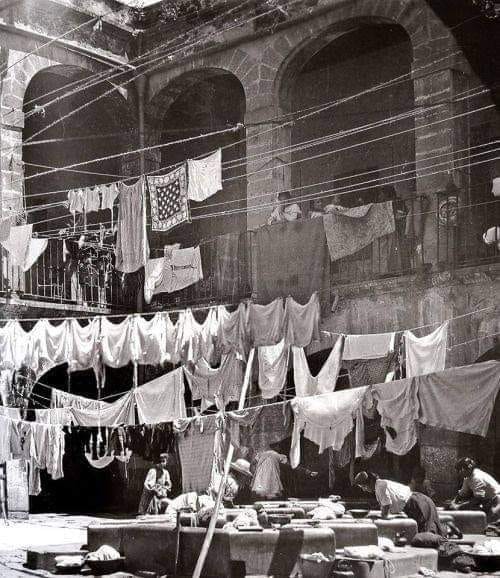

They were little rooms where people lived as if they were little mice.” The size of the rooms really only allowed the inhabitant enough room for a sleeping area, so most activities were carried out outdoors in the patios or on the street.

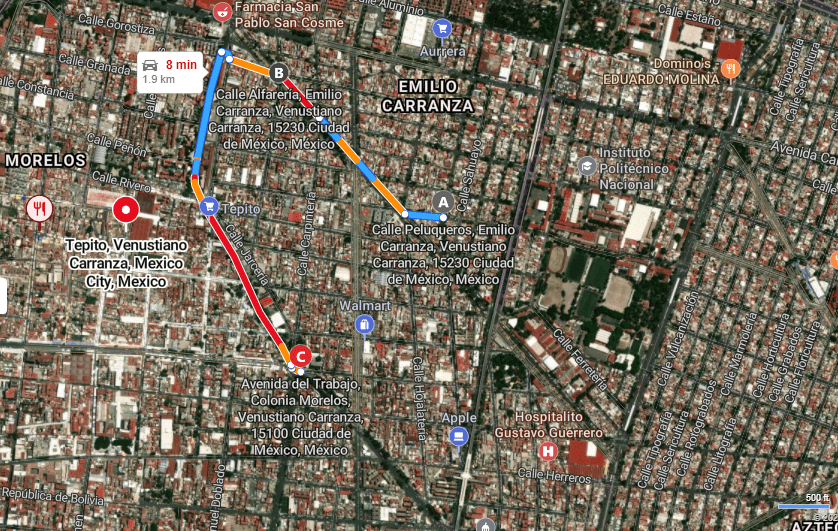

The floorplan layout of the vecindad above demonstrates how small each room was and how cramped living conditions were. This vecindad, La Casa Grande was originally built in 1910 in Tepito in the area between the streets of Peluqueros, Alfareria and Avenida del Trabajo and occupied an entire block.

It was a single story building and contained 157 windowless one room apartments, many of which had mezzanine floors added (which were connected by an internal stair) and housed 700 people. Usually the number of people living in each apartment surpassed space availability and the floor was also used as a sleeping area. The vecindad had four long concrete paved patios about 5 metres (15 feet) wide with rough wooden ladders near most room entrances that lead to the flat roof which was crowded with lines of Iaundry, chicken coops, dovecotes(1), pots of flowers or medicinal herbs and tanks of gas for cooking. In front of each room was an azotehuela (2) that was used as a lobby and where the kitchen and toilet were located.

- freestanding structures designed to house pigeons or doves.

- Mx. An interior courtyard, roofed or not, of a house or an apartment.

Just to expand a little on the azothuela. According to the literary editor Larousse latam it is a Mexicanismo (a word, phrase, or mode of expression distinctive of Spanish as spoken in Mexico) which translates variously as…

“Zotehuela” o “azotehuela” se refiere a una azotea pequeña, aunque también suele considerarse como tal al traspatio que sirve de cuarto de servicio en los apartamentos.

“Zotehuela” or “azotehuela” refers to a small rooftop (or roof terrace), although it is also often considered to be the backyard (traspatio) that serves as a utility room (service room) in apartments.

La Casa Grande was a small world of its own. You entered it via one of two narrow, inconspicuous entrances on the east and west sides, each with a high gate that was open during the day but locked every night at ten o’clock. Anyone coming or going after hours had to ring for the janitor and pay to have the door opened. The vecindad was enclosed by high cement walls on the north and south and by rows of shops on the other two sides. These shops included food stores, a dry cleaner, a glazier, a carpenter, a beauty parlour, and the neighbourhood market and public baths. These businesses supplied the basic needs of the vecindad so that many of the tenants seldom left the immediate neighbourhood and were almost strangers to the rest of Mexico City. The building was badly damaged in the earthquake of 1985 and in 1986 it was completely rebuilt in 1986 and transformed into apartment buildings.

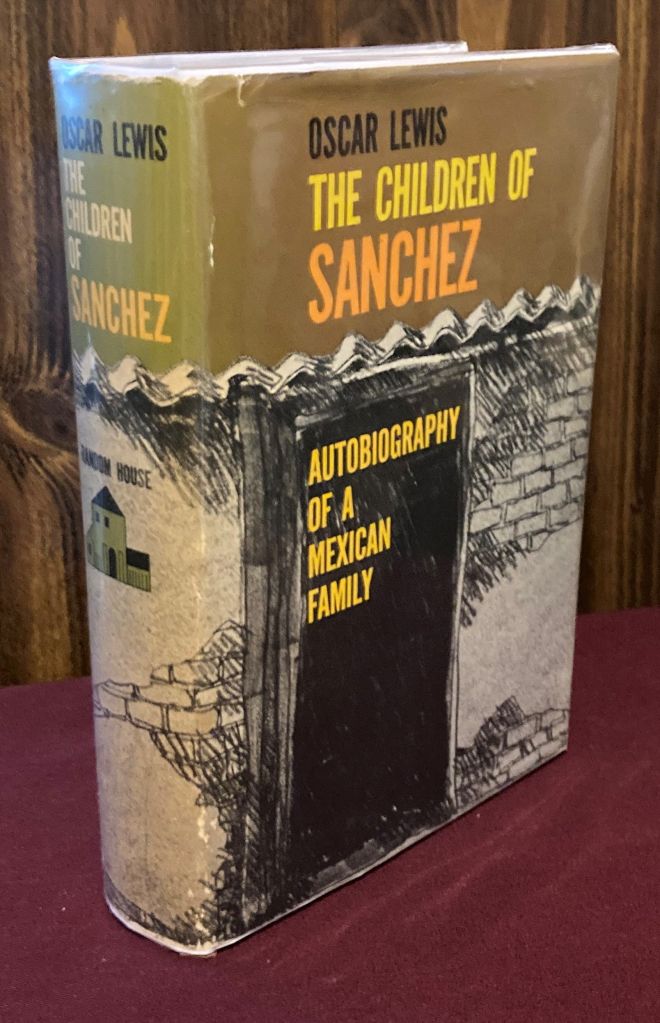

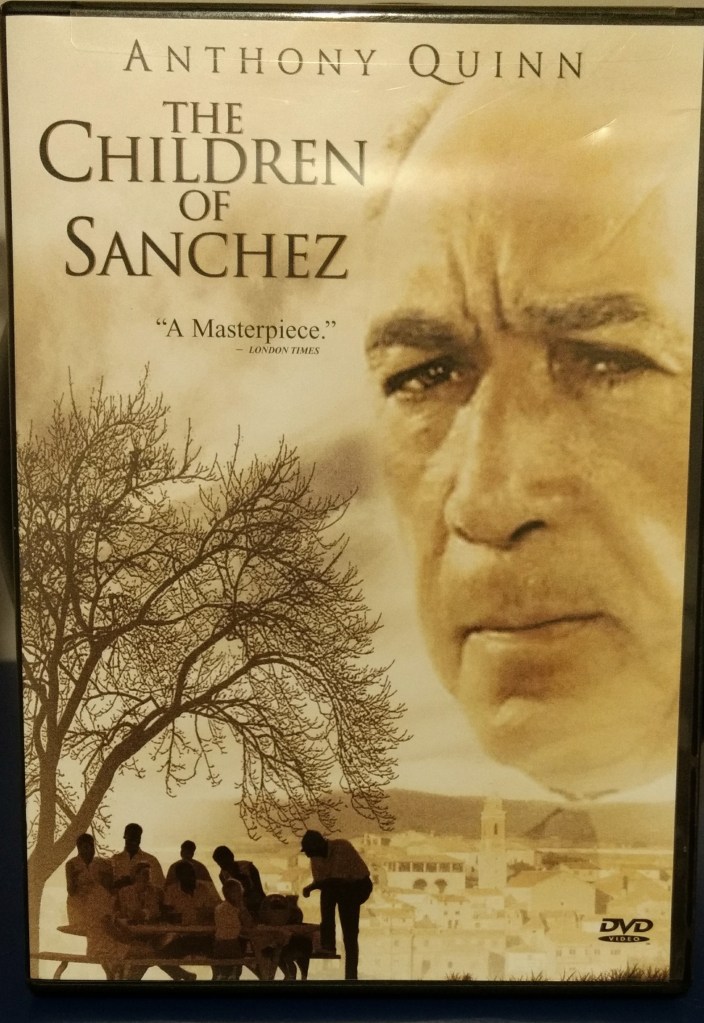

The vecindad of Casa Grande played a starring role in the 1961 book “The Children of Sanchez”. The content of the book itself consists of the life stories and accounts of Jesús Sánchez, age fifty (patriarch of the family), and his four children Manuel, age thirty-two; Roberto, twenty-nine; Consuelo, twenty-seven; and Marta, twenty-five. The book was written by the American anthropologist Oscar Lewis and most of the interviews and the recorded events centre around the Casa Grande Vecindad, a large one-story slum settlement, in the center of Mexico City. The book was banned in Mexico for a few years because of criticisms expressed by members of the Sanchez (not in fact their real name) family regarding the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) government and Mexican presidents such as Adolfo Ruiz Cortines and Adolfo López Mateos (and also due to it being written by a foreigner) before pressure from literary figures resulted in its publication. Formal charges were made against Lewis and the publisher by the Mexican Geographical and Statistical Society, accusing them of writing and publishing an obscene and denigrating book. These charges were eventually dismissed. A film based on the book and with the same title was directed by Hall Bartlett and was released in 1979. It stars Anthony Quinn as Jesús Sánchez

Not much has changed in Tepito even to this day

The vecindad known as El Hormiguero (the anthill) in Tepito

Etymology of the Vecindad.

It’s the semi-communal character of these buildings that gave the vecindades their name, whose etymology, comes from the word “vecino,” or “neighbour.” The term relates to the fact that this is less an architectural typology, but starts from a communal or social way of living. “It’s a social process of understanding housing rather than an architectural process of understanding housing.”

Mexican vecindades have become a badge of distinctly local identity. Although many hold Mexico City’s vecindades in disregard for the poverty of residents and perceptions about sanitation and crime, they have become synonymous with a particular idea of Mexico and nostalgia for a certain period in its history.

Because they are community spaces, their structure had as its purpose the scheme of coexistence between neighbours who had a shared central patio and at least one more communal space for the laundry area. In the films from the Golden era of Mexican Cinema (more on this later), we meet the gossiping concierge and the laundry rooms where the housewives gather to discuss everything that is happening in the building.

There were still hierarchies even in this democratic and communal space. To avoid steep walk-ups, families desired apartments closer to the ground floor— although not on the ground floor itself, which tended to get little light and to be exposed to the patio’s noise and activities. In vecindades with multiple internal patios, it was considered desirable to live on the one nearest to the street (hence references in Mexican popular culture to “el quinto patio,” the fifth patio, being synonymous with poverty).

“There is this mystique” around neighborhoods, says Celia Arrendondo, professor emeritus of architecture at Tec de Monterrey in Monterrey, Mexico. “Of the romances that happen there, of the neighborhood matriarch taking care of the children, of the people who come to ask for advice and food. “To share bathrooms and areas where they wash, and that is something that would create community.”

These relationships between those who inhabit them have made the vecindades a place to which Mexican culture frequently returns, in the form of films, television shows, telenovelas (soap operas) and songs that celebrate them and are part of how Mexico visualized itself in the twentieth century.

AIejandro M. Rebolledo writes that “Vecindades can also be seen as segregated islands, separate from the rest of the city. This double quality of the vecindades has a strong influence on the mentality and conduct of their inhabitants. For them the vecindad represents a relatively tranquil space, sheltered from the chaos and exterior dangers of the city; a space which gives them protection and security and which allows them to live their life in the way they desire. Within them we find strong feelings of unity. solidarity, friendship, love and compadrazgo (1). On the other hand, the promiscuity within the vecindades led to arguments and fights among the inhabitants. Although the need for a certain degree of privacy or intimacy is critical, the feeling of belonging to the vecindad is strong”

- Comparadzgo : a complex social phenomenon that holds deep cultural and social significance in Latin American societies. It encompasses various forms of fictive kinship, creating networks of relationships that extend beyond immediate family ties.

The architectural layout was also used by the Catholic Church when constructing convents, hospitals and schools.

The vecindades born in the historic center of the city from these viceregal houses and convents built from the 16th century onwards, when the city was founded, were adapted or abandoned.

When a someone entered a convent or applied to be ordained into one of the religious orders of the time, their family contributed a dowry to the congregation. The order received cash or real estate. But when the number of men and women interested in entering the orders decreased, they had to take action to survive.

What the nuns did to survive was divide up the properties they owned to sell or rent them to individuals. For example, the Carmelite based Teresian nuns of Santa Teresa, the Poor Clares, Franciscan nuns of the Order of Saint Clare and the Dominican nuns of Santa Catarina set aside a section of their convent to build homes and rent them out. In this way, religious corporations came to own 35 to 40 percent of the real estate market.

Photo: Courtesy Book Neighborhoods of Puebla by Rodolfo Pacheco Pulido

Breaking up properties to rent them not only occurred within religious corporations (convents). Between the 17th and 19th centuries it was recorded to a lesser extent in the religious brotherhoods and productive artisan guilds (1) of the city.

- Guilds (gremios), self-governing organizations that established and enforced rules for the production and sale of specialized goods. Members were artisans such as shoemakers, silversmiths, carpenters, and harness makers. Guilds flourished chiefly in the colonial era. Parents, guardians, or the state placed young boys with master artisans for set periods. Contracts stipulated living conditions in the master’s house and the skills that would be taught, and explicitly sanctioned the master’s authority to discipline his apprentice. Guilds and their members were grouped into vecindades, forming neighborhood associations that lived on the same street or part of a street between colonias (neighbourhoods). These associations served to protect themselves and take care of common matters (cleaning, surveillance, fire prevention…).

The 19th century brought industrialization and the collapse of the country’s largely agrarian past, leading thousands of people to migrate to cities in search of work.

This upheaval in Mexico meant that these buildings were not destined to remain as elite residences or church property for long

Due to the laws of confiscation and nationalization of ecclesiastical property (1856), during the second half of the 19th century, the number of vecindades increased because the properties that had belonged to the Catholic Church since the viceroyalty, became federal property, including temples and the convents.

“Convents like La Concepción, Santa Rosa, San Roque and Santa Catarina were transformed into the most diverse vecindades consisting often only of a communal laundry and a collection of dozens of rooms.

The wealthy began to flee the city centre, while mid-19th-century Reform Laws saw church property nationalized. Slowly, these buildings began to empty and working class renting families moved in, as the rooms around the patios were the only housing they could reasonably afford.

by Rodolfo Pacheco Pulido,

Photo: Courtesy Eduardo Fernández Huesca

These families slept in cramped conditions, with multiple people occupying rooms originally meant to be sleeping quarters in a larger, single household. While in more recent decades, residents have added indoor cooking and washing facilities and mezzanines that create extra space, the vecindades originally lacked private amenities, making the central patio a hub for daily activities. That setup created a deeply communal way of life for inhabitants — relationships with neighbors grew as complex, involved and profound as those with one’s own family.

With the strength of the Porifiriato (1876–80; 1884–1911), new foreign merchants arrived in the city, who bought old houses and rebuilt them, some for their own homes and others as rental properties. This is how several vecindades were rebuilt. These vecindades were characterized as places where people with limited resources lived.

This real estate market was maintained until the Revolution (1910–20). From here, another rupture arose again because the bourgeoisie stopped consistently managing its properties and they began to deteriorate.

At the end of the 1930s (20th century) the old colonial houses began to be demolished to convert them into apartment buildings. The first case was the convent of San Gerónimo which, in 1936, was demolished to build the art deco styled Edificio María, located at Av 5 Oriente, C. 2 Sur in Pueblas Centro Historico. It was the first apartment building in Puebla.

In 1942, the decreto de congelamiento de rentas (Rent Freezing Law) was enacted (as was the Ley de Protección de Monumentos – Law on the Protection of Monuments), which ordered that landlords or neighbourhood owners not increase the amount of rents of tenants who rented homes with dates prior to 1942 or allowed the demolition or remodelling of colonial buildings or buildings of historical interest without prior expertise from the “competent authorities”. These laws became a cause of architectural deterioration, since the old owners abandoned the buildings without carrying out any repairs and allowed the properties to suffer superficial and even structural damage. Homeowners stopped investing in and improving their properties. Paradoxically, if these repairs had been carried out, the inhabitants of said properties would be the most affected, since rents would rise, or they could be thrown out of their homes. With this, not only the historical heritage of the area deteriorated, but also the quality, already poor, of housing for people with low economic resources.

This affected the real estate market in Puebla and caused many low-income families to continue overcrowding in the neighbourhoods.

Most vecindades were demolished to build large buildings, some for offices and others for multi-family apartments, which were also built for low-income sectors.

When Puebla was declared a World Cultural Heritage Site in 1987, these buildings disappeared and those that remained are practically destroyed, left in a deplorable state, and some are no longer inhabited. In the best of cases they have been recovered to establish restaurants and/or boutique hotels.

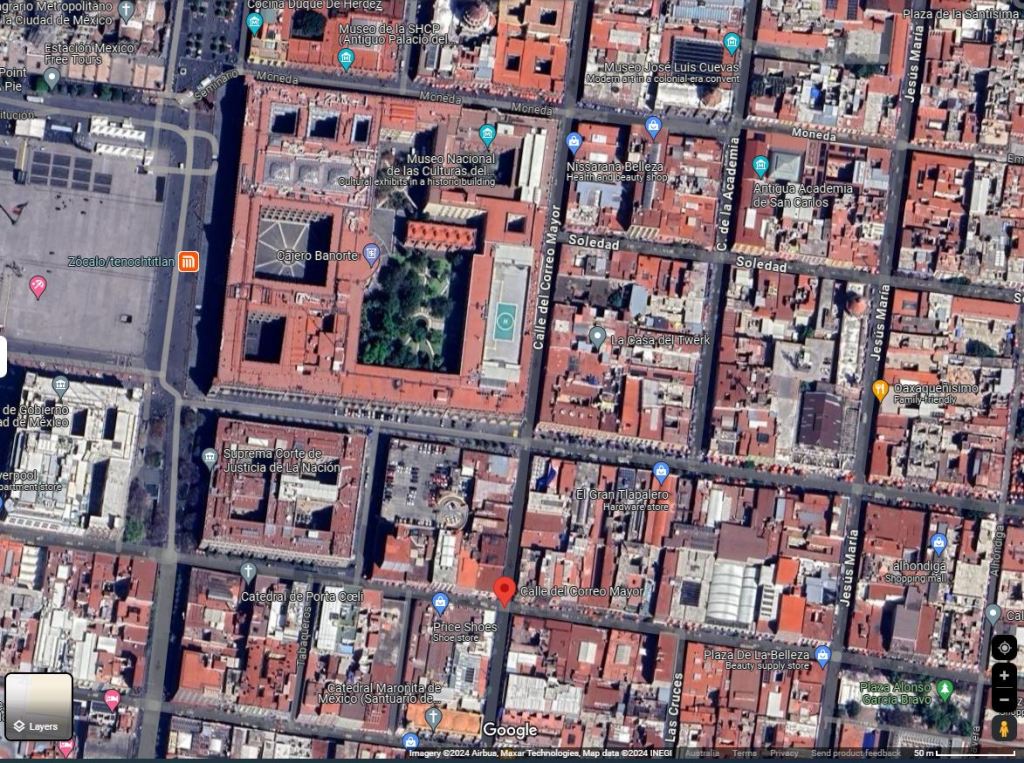

In the Historic Center of Mexico City there was the largest number of vecindades, which were distributed among the colonias of Tepito, La Lagunilla, Mixcalco, San Miguel, San Antonio Abad, San Pablo, Santo Tomás, San Juan, Peralvillo and La Merced.

In addition to the vecindades located on Mesones and República de Uruguay streets, some others are still alive. One of them is located in the Tepito neighbourhood, on Peralvillo street number 15, which was built more than 300 years ago, it is the oldest in the city, it has 144 homes and since 1981 it has been listed as a heritage building with historical and cultural importance by the INAH.

According to data from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) from 2011, of the 2,411 properties catalogued as historical and cultural heritage, 20.5% correspond to multi-family buildings with common uses, which are known in the City of Mexico as vecindades.

From the 16th century until the early 20th century, vecindades comprised the majority of the housing stock in Mexico City. In the 1943, due to the ideas of Functionalism (1), vecindades ceased to be built and were relegated as an old and traditional dwelling form in the centre of the city

- In architecture, Functionalism is the principle that buildings should be designed based solely on their purpose and function. It arose in the early 20th century as a reaction to the ornate, decorative styles of the past, such as Art Nouveau and the Beaux-Arts style.

Many of the vecindades that were in that area no longer exist, in their place large buildings and housing units were built and those that do remain are in very poor condition.

Like the one located in Peralvillo # 15, in the heart of Tepito, which claims to be the oldest neighborhood in Barrio Bravo. It was built in 1713, it is said that before the neighbors arrived, it was a convent. Since 1981, it has been protected by the National Institute of Anthropology and History.

Today, the number of vecindades in the city has dwindled, and the ones still standing are often in serious disrepair; but they continue to mean something to the urban landscape and to many people living in it, for whom the old buildings form a nostalgic but essential part of what it means to be Mexican.

Decay and Destruction

Many of the old stories representing fictional vecindad communities carry on today. The real-life vecindades, however, are a different story. As the city has changed around these historic buildings, their numbers have dwindled and many are now in such disrepair that their residents are subject to squalid conditions.

This decline has been steadily encroaching for almost a century.

The long decades without major redevelopment downtown had negative effects on the vecindades’ condition, but they also preserved the historic centre’s character for longer than elsewhere in Latin America. “What makes [Mexico City] different is there was not a kind of massive renewal or redevelopment of downtown in the period between the ‘50s and ‘70s, which happened in most Latin American cities,” says Diane Davis, a professor of regional planning and urbanism at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. “After the 1985 earthquake there were efforts to revitalize the property market, but it didn’t extend to completely razing the downtown.”

The continued existence of low income, dense housing forms like vecindades in the city center — despite major post-earthquake reinvestment in the city’s downtown — meant there was also a higher concentration of low income residents in the downtown core, Davis says. “You wouldn’t see that in other cities to the same degree,” she says.

A recent photographic project by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History found evidence of more than 480 vecindades in the city centre in 1925 . It is difficult to find estimates of how many survive today as residential homes, although some estimate the number barely reaches 100. Meanwhile, those that survive are often in poor condition and may have problems with crime associated with drug trafficking.

Stories from the Heart of the City

Where thousands and thousands of stories worth telling have been lived for many years!!

Greetings from the heart of the city!!

In a May 25th (2017) article in Etcetera by Mariano Yberry a precovid investigation of various vecindades is taken. Mariano notes that the most marked of the remnants of the vecinidades of the past lie at the very heart of Mexico City and that the vibrancy of the traditions of Mexicanness created by the communal living in these vecindades is bowing under the relentlessly crushing march of progress. He notes that “in the face of gentrification, in the face of multiculturalism, in the face of the advance of the voracious market that transforms every millimetre of public space into a place to sell cell phone plans, the traces of our past are increasingly hidden, our traditions flee from the city progress and it is more difficult to find a little of what was once around the corner.”….”the past has fallen behind among the thousands of stores that today crowd the centre with a supply that sometimes seems to exceed demand”

According to data from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), the first vecindades were established at the end of the 18th century, and located mainly in the centre of the city.

Calle Mesones, which was once a resting place for viceroys and the wealthy class of the colony is where Mariano’s journey begins.

Walking down the entire street of Mesones and finding nothing but an obsessive repetition of stationery and school supplies stores and locating old vecindades transformed into mini shopping centres he strolls upon a small pirate movie stand placed right next to an old wooden gate just before the intersection of Mesones and José María.

He approaches several people with queries about the neighbourhood but is viewed with suspicion and is hurriedly moved along. Moving down to Manzanares via the Republic of Uruguay and the Circunvalación ring his path is blocked by chacas (1) who, after a brief interaction, tell him to go do his “homework” elsewhere.

- noun (masculine) A gangster, or malandro from Mexico City. Malandro – variously translated as rascal, hooligan, scoundrel, ruffian, crook, hoodlum, miscreant, bad egg, criminal, evil person (you get the idea)

Manzanares, Past and Present

That “elswhere” is none other than the Barrio Bravo, Tepito (1). Now, in Tepito, the vecindades that “once cooked delicious beans for a family of at least eight people are now warehouses for marijuana and methamphetamine.” He warns that it is a place that one should not travel alone, asking questions is dangerous and that it is better if one shows up with a guide, a previous “client” of those same dens that you can procure your weed or meth from. Arriving at the entrance of a vecindad with a green gate located somewhere in the perimeter delimited by Peralvillo and Tenochtitlan, Peñón and Matamoros they proceed up to the second floor and enter an apartment past a young woman huffing solvent who offers them a turn. After a brief interaction with the dealer inside they move along.

- Tepito is one of those places you’ll find on “Dark Tourism” websites as a dangerous place to visit. It is known locally as THE place to vist if you’re looking for fayuca* or pirated goods and has a reputation for high crime rates. In another article published by El Universal the police raided a vecindad known as “La Fortaleza” with the aim of searching 144 homes; However, they only investigated 73, since the rest were used as warehouses and clandestine piracy laboratories (laboratorios clandestinos de piratería). First reports noted that the building belongs to La Unión Tepito (a large criminal group indigenous to Mexico City) and that 30 people were detained, with various drugs, 13 short weapons, seven long weapons, a grenade launcher and five grenades also being seized by police.

*fayuca – “Fayuca” is a unique word that is often heard among Mexican society. This is a term used to describe some type of product that was introduced “por debajo del agua” (underwater). It is very normal that some establishments offer a wide variety of items of all kinds such as: Clothes, shoes, backpacks, makeup, speakers, headphones, stereos, perfumes, watches, etc., at a fairly affordable price. Distrust or joy in the consumer arises when he or she realizes that it is a “good quality” object that is cheaper than it should be. According to the some, the reason why the things that were smuggled into the territory began to be called “fayuca” is because in prisons the “improvised stores that certain inmates set up” began to be called that way. in the courtyards to sell trinkets to other prisoners.” Likewise, over time the word became associated with the trade of “trinkets” and, in the north of Mexico, the name “fayuqueros” began to be used to refer to the “characters who toured the towns, first on donkeys and then in trucks, selling almost always contraband merchandise .”

Leaving the area they return to the much safer Manzanares, a place one can enter without a guide, and move down through the mercado de pulgas (flea market) in the middle of Plaza Roldán. They continue to Lecumberri, turn left and one block later, the street becomes República de Colombia.

Between República de Argentina and Calle del Carmen, they find three vecindades (one with the overpowering scent of shoe soles) which they enter. Marianos questions regarding the place however are once again met with suspicion and the are angrily moved on.

You’ll find plenty of “fayuca” here

Having no real success at procuring any information about these buildings they end their sojourn in Plaza Garibaldi with a litre mug of strawberry curado pulque and the lamentations of mariachis floating in the afternoon heat. “México, lindo y querido / si muero lejos de ti”. (“Mexico, beautiful and dear / if I die far from you.”)

Editorial El Universal

In the Mexico City based newspaper El Universal, Karen Esquivel published an Editorial article containing a series of interviews resulting from a tour of vecinidades taken by Mochilazo en el Tiempo (Backpack in Time). I would like to share a few excerpts of that tour.

One of those interviewed was the 93 year old Joaquín Moran Álvarez who lived in a vecindad at number 119 on calle de Mesones in 1942.

Joaquín said the building was built by the Augustinians (1) initially as an inn (2) which is how the street got its name (mesone = inn). The area was dangerous even at that time and he relates the story of the owners at that time, being a wealthy family, who the patriarch and matriarch of were murdered in a robbery. He then went on to show the original fixtures and building elements that have not changed since that time. He said that at that time he only paid 15 pesos a month for rent. These “rentas congeladas” (frozen rents) were designed to support low income families but they were done away with in 2001. Don Joaquín remembers that the atmosphere in the vecindad was always very nice and calm. “I thank God, my life here has been very good. When I first came to live, in the 1940s, there was a tram that went from Tlalpan to Xochimilco,” says the 93-year-old man. “The vecindades are nearing their end” he says. “These traditions are ending, many of the vecindades have either been demolished or modernised”

- Augustinians are members of several religious orders that follow the Rule of Saint Augustine, written in about 400 AD by Augustine of Hippo. Augustinian friars first set foot in Mexico in 1533, shortly after the arrival of their Franciscan (1524) and Dominican (1526) peers. They established a convent in Mexico City, adding a novitiate within a few years to train new friars for ministry and grow their religious community in New Spain. The Augustinian friars were the first Christian missionaries to settle in the Philippines.

- Inns are generally establishments or buildings where travelers can seek lodging, and usually, food and drink.

Another interviewee, the 90 year old señora Viviana, this time at 171 República de Uruguay, who moved into interior tres at the age of 27 after getting married spoke of how much life had changed in her 63 years living here. “I like living here, before we all talked here, we never fought with anyone, we all got along well,” She mentions that previously there were eight families in this vecindad but since the 1985 earthquake which devastated Mexico City almost everyone had left. “Now there is only me and two other neighbours left.”

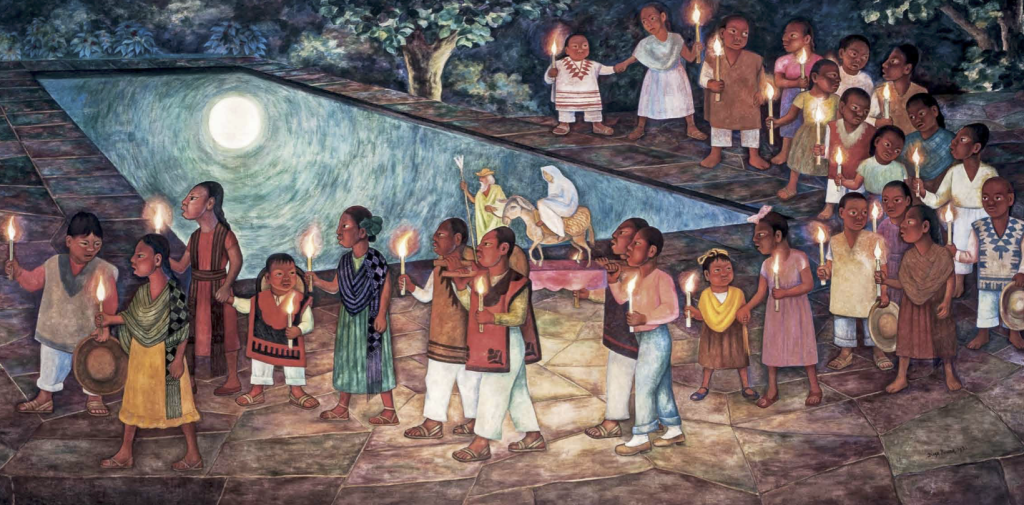

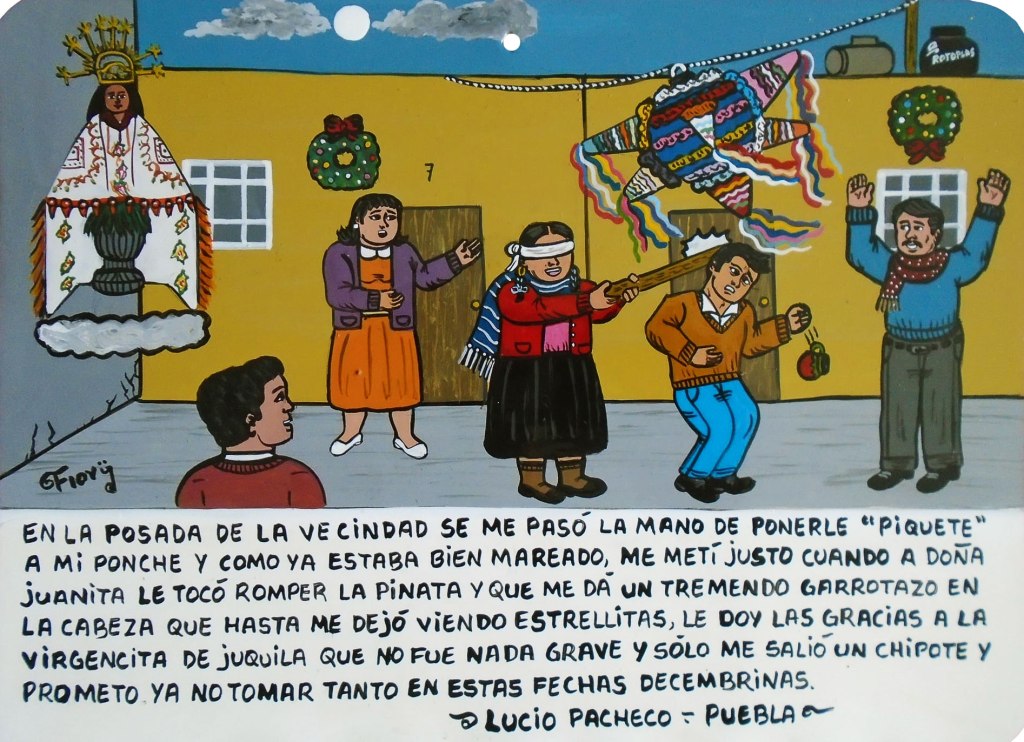

Both señor Joaquín and señora Viviana remember that one of the most deeply rooted traditions in the neighborhood were the posadas (1).

- The word posada means inn or lodging . Posadas are a series of fiestas navideñas (Christmas parties) that traditionally take place December 16–24. Las Posadas commemorate the journey that Joseph and Mary made from Nazareth to Bethlehem in search of a safe refuge where Mary could give birth to the baby Jesus. At the beginning of a posada, people are divided in two groups, the ones “outside” representing Mary and Joseph, and the ones “inside” representing innkeepers. Then everyone sings the posada litany together, re-enacting Mary and Joseph’s search, going back and forth until they are finally “admitted” to an inn. After this tradition, the party proper starts.

at Children Hospital of Mexico

Folk art in the form of a “retablo”. A Mexican retablo is a small devotional painting, using iconography derived from the Catholic Church. Most were created for giving thanks to a sacred person or saint who intervened in an event that posed a threat to their well-being. The creator would often paint the dangerous scenario they had experienced, write a description underneath, and note the time and whereabouts of the event.

I put too much liquor in my punch at the Christmas party in my vecindad. Since I was getting tipsy, I came where doña Juanita was about to hit the piñata and she gave me such a tremendous blow in the head that I even saw stars. I give thanks to the Virgin of Juquila because nothing serious happened and I only got a lump. I promise not to drink so much on these December holidays.

Lucio Pacheco, Puebla

“In December, traditional posadas were held, the litany was sung, piñatas were bought, we all collaborated for the punch, and we bought cuetes chinos (1), lights, depending on what we gathered,” says Don Joaquín. At the end of each night, Christmas carols were sung, children broke piñatas and everyone gathered for a feast.

- Cuete (also cohete) = fireworks; cuete chinos = Chinese fireworks; the word cuete also has an interesting (and somewhat relevant meaning, considering the celebratory nature of the event in general) : cuete = adj. Max colloq. [ Person ] Who has an alteration in their physical or mental capacities due to excessive ingestion of alcoholic beverages ; and relates to the Nahua Cuetxecatl , leader of the Cuetxecas , who was noted as drunk in the past (see Sobarzo, Vocabulario Sonorense)

The Architecture Evolves

The multi-family dwellings, the vecindades of the last centuries evolved into another kind of multi-family dwelling in the next century.

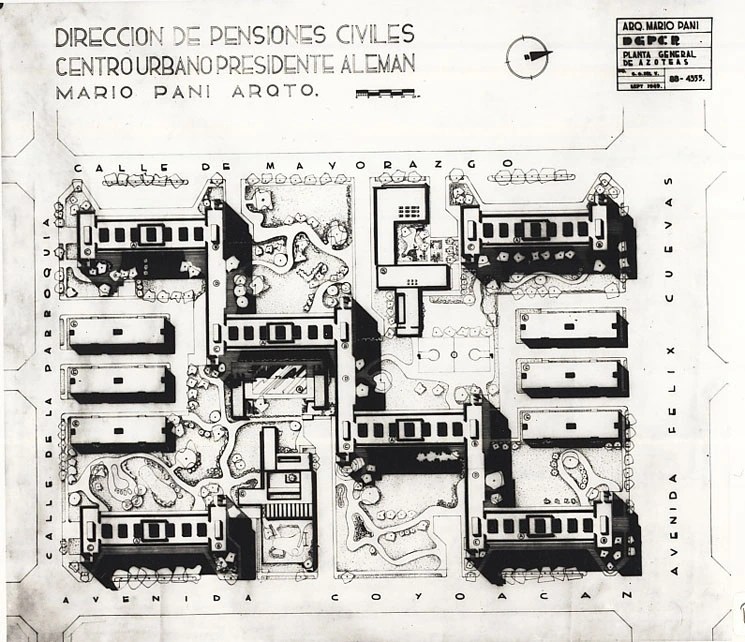

One of the symbols of the rise of the middle class and the entrance to modernity in Mexico was the construction of the famous complex, Conjunto Urbano Presidente Alemán (Presidente Alemán Urban Complex, known as the CUPA), designed by the architect Mario Pani which was the first of many such high-rise housing complexes that followed (1). These buildings became known as “multifamiliars”, a word which was coined by the inhabitants of Mexico City, originally with a certain sense of disdain towards a building that is occupied by a very large number of families. Mario’s design was implemented after he prevailed in a contest launched in July 1947 by the Dirección de Pensiones Civiles with his proposal to create a structure with “the optimal use of the land; the biggest population capacity; and the conditions of spaciousness, comfort and size of the dwellings” (in relation to the cost and quality of construction)

- Other housing complexes by Mario Pani are: Centro Urbano Presidente Juárez, 1950-1952; No. 9 and 7 Neighboring Units, 1950-1951; Centro Urbano Santa Fe, 1953; Nonoalco-Tlatelolco Housing City, 1962-1964; Centro Urbano John F. Kennedy, 1965; Centro Urbano Lindavista-Vallejo, 1965-1966.

The complex occupied a so-called super block, encompassing an area of 40,000 square meters (m2), within an urban low-density context in the southern part of Mexico City, with a total of 1,080 apartments for rent. The plot needed few perimeter parking spaces, as it was well connected by public transport, flanked on the western side by Avenida Coyoacán, an important route to the centre of the city with a streetcar service.

The housing complex included six buildings with a ground floor and 12 apartment floors, north-south facing, and six more buildings with the same orientation but with only three floors. It included a nursery, a kindergarten, a pool and public spaces for sports, gardens, and administrative offices and was in essence a small town that provided its inhabitants with all the services that modern life had to offer at the time.

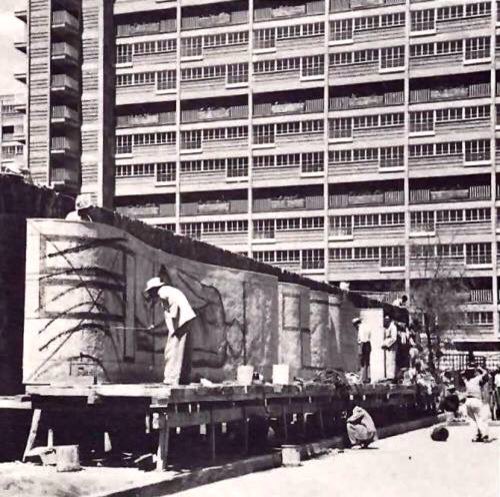

Noelle (2021) writes that the famed muralist José Clemente Orozco was supposed to paint an exterior mural, La Primavera [Spring], on an undulating and fragmented concrete wall at the site “during the summer of 1949 (…) On September 6th he sketched the outlines for a figure (…) for the Multifamiliar Alemán (…) The next morning (…) his family found him dead from a heart attack.”

The remnants of that mural still exist today

This multifamiliar still stands.

Another of Panis works, the Multifamiliar Juarez (Centro Urbano Presidente Juarez) has not been so lucky.

The grounds for this construction initially was a cemetery, the Panteón General de la Piedad, for only a short period from 1871 to 1882 but which was abandoned and fell into disrepair. in 1922 a school was built on the site and the following year a sports complex designed by the architect José Villagrán started construction (which in turn was demolished in 1949)

In 1950, via a mandate by the then President Miguel Alemán Valdés, the construction of a housing unit designed by Pani began. This project sought to be the largest of its type in Mexico City, with around 984 apartments, 19 buildings and a capacity of more than 3 thousand people.

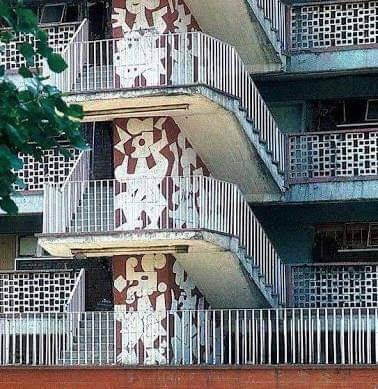

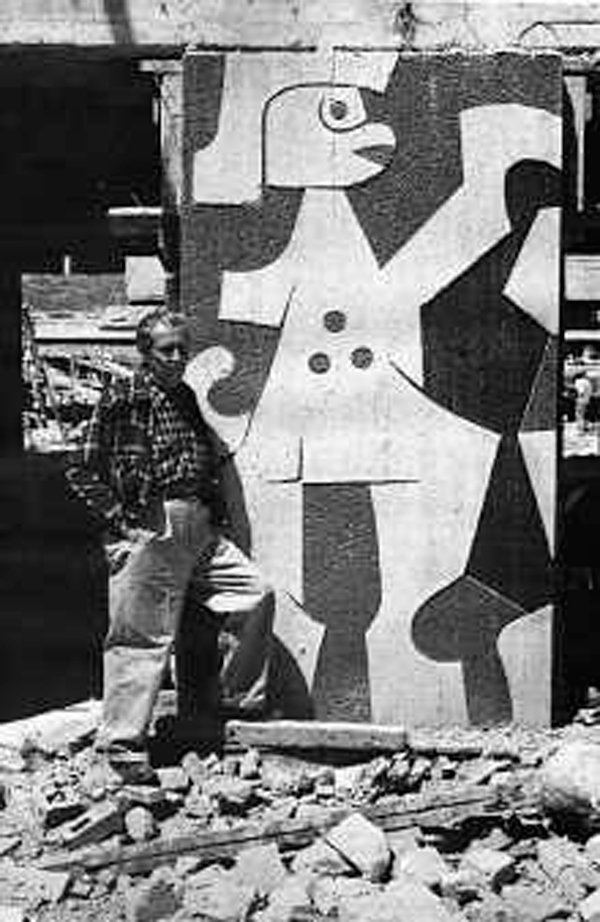

Mario also sought integración plástica in his design and invited the artist Carlos Mérida to create a series of murals in the complex. This pictorial project was the largest in Mexico up to that time, as it covered nearly 4 thousand square meters.

- integración plástica or the “Plastic arts” is the set of artistic manifestations constituted by painting, architecture, sculpture, textile art and all human expression that transforms materials into images and objects with artistic meaning. The movement, headed by the leading architects of the time in collaboration with important artists searched for an intersection between the visual arts and architecture. Mario Pani was one of the pioneers in the forefront of this field. (Noelle 2010)

Mérida’s work with the integration of the plastic arts and architecture was nothing short of revolutionary. Buildings were not just canvases but art themselves. He asserted that “the old concept of Mexican Muralism (Montenegro, Rivera, Siqueiros, Orozco) has stopped existing . . . the painting must be fused with the architectural body and should not be taken as mere ornamentation.” (Noelle 2010)

Although the planning of this unit was carefully reviewed before its inauguration in 1952, the foundations did not receive adequate reinforcement; For this reason, the 1957 earthquake caused significant damage to the structure of several buildings, of which only a few were corrected. Then in 1985 tragedy struck.

During the earthquake of September 19, 1985, numerous structures in the complex collapsed and others suffered irreparable damage .

Although there are no official figures, some versions claim that around 80 human bodies were found among the rubble. This powerful earthquake destroyed some of the tallest buildings in the Multifamiliar and, in October of that same year, the demolition of the rest of the affected buildings in the area began. In total, 15 of the 19 buildings in the complex completely disappeared.

Only four low-rise buildings of the Multifamiliar Juárez survive. In the place occupied by the other living spaces, the community decided to place a green space, which is currently known as the Ramón López Velarde park

The remains of Carlos Mérida’s work were transferred to the Unidad Habitacional Fuentes Brotantes (Fuentes Brotantes Housing Unit) , south of the capital.

These buildings (both vecindades and multifamiliars) have played (and continue to do so) a huge part in the psyche of the Mexican, particularly the capitalino, the defeño, the chilango (or however you wish to refer to the inhabitants of the CDMX)

I Googled “Chilango Pride meme” and this is what Google told me….WTF Google??

I think it might be harder than that to offend a Chilango.

Piss off Google.

Casas de Vecindad in Popular Culture

These multi family constructions (both vecindades and multifamiliars) have been settings for movies, shows and songs.

According to the text “Vecindades en la Ciudad de México: la estética de habitar” (Vecindades in Mexico City: the aesthetics of living” by Casa Lamm (Hernandez Lozano 2013), these spaces generated “the unity and creation of joint identities of their inhabitants around the physical space that responds to the social condition of their individuals.” In this sense, the patio fulfilled a function of coexistence where most of the daily activities, posadas and other celebrations were carried out.

These neighbourly relationships have made the vecindades a place Mexican culture frequently returned to, as movies, shows, soap operas; and songs celebrating them formed part of how Mexico visualized itself in the 20th century.

in the mid-20th century, cinema transformed our image of what these community houses were, and that is how we got to know the Vecindades of the two-leaf hallway and the staircase in the centre with its ironwork railings and its spacious rooms.

Vecindades in the cinema of the Mexican Golden Age

Mexican cinema in its golden age that spanned from 1936 to 1957 portrayed many of its stories within these homes with large patios where you could watch people playing, talking and celebrating the traditions that were a reflection of a particular social class.

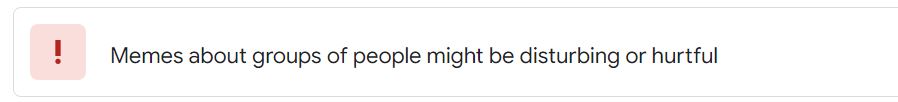

Movies like Nosotros los Pobres (We The Poor), (1948), directed by the filmmakers Ismael Rodríguez and Pedro de Urdimalas and starring the actor Pedro Infante, was a film that dealt with the life of a nice, poor, hard-working and honest carpenter who was known as Pepe “El toro” and who has a daughter named Viruta, played by “Chachita”.

The film describes the life of the poor at that time. It is set in a vecindad. Different problems are represented in the central courtyard of this film. In the background of the recording frame you can see many people playing, drinking or simply working.

Other films in this genre such as El Quinto Patio (The Fifth Patio) (1950), Casa de Vecindad (“Vecindad house”)(1951) and El Rey Del Barrio (The King of the Neighbourhood) (1950) helped create a national image of the vecindad and its inhabitants: a tightly knit community where hardworking labourers, family matriarchs and various other kooky personalities formed a community that fought, loved and supported one another — and often dreamed of eventually leaving.

Return to the Fifth Patio (Retorno al Quinto Patio) , also from 1951, is another of the films that allowed us to see the essence of the way of life in these spaces. This film tells of the life of a poor family that is about to be evicted from their home because they do not have the resources to pay the rent.

A poor amateur singer is deeply in love with his boss’s daughter,

but the spoiled girl rejects him because he has no fortune.

In the 1970’s version, Ramon is a guy who lives in a vecindad, in the “fifth courtyard” in urban poverty. However, he aspires to the love of the daughter of his employer, a woman of another social class. Que tragedia no?

All of these movies focus on the poverty of the inhabitants.

The well known Mexican comedian, actor, and filmmaker Mario Fortino Alfonso Moreno Reyes, known more commonly as Cantinflas appears as the doorman of a vecindad in the 1950 movie El Portero. An internationally known clown, acrobat, musician, bullfighter, and satirist, Mario was most famous for his character Cantinflas, the comic figure of a poor Mexican slum dweller, a pelado (1), who wore a tattered coat, trousers held up with a rope, a battered felt hat, and a handkerchief tied around his neck.

- Pelado – Literally meaning “peeled” (barren, bleak, or exposed). In Mexican society, pelado is a term said to have been invented to describe a certain class of urban ‘bum’ in Mexico in the 1920s. The term referred to the penniless urban slum-dwellers or homeless, sometimes migrants from the countryside and un- and under-employed. “Pelado” also means “bald” or “shaven” head, referring to the custom in jails and assistance institutions to cut the inmates’ hair in order to prevent lice and other parasites. The Mexican philosopher Samuel Ramos from Zitácuaro, Michoacán is purported to have said “The pelado belongs to the lowest of social categories, and represents the human detritus of the big city.”

The 1951 film Casa de vecindad shows the life of the inhabitants of a Mexico City vecindad, where the owner, the stingy landlord Don Clemente (David Silva) is reviled by its occupants.

Occupants of the vecindad have a series of extramarital affairs, which trigger rumours and gossip among the families. Desperate housewives of the CDMX

Tourism in Tepito.

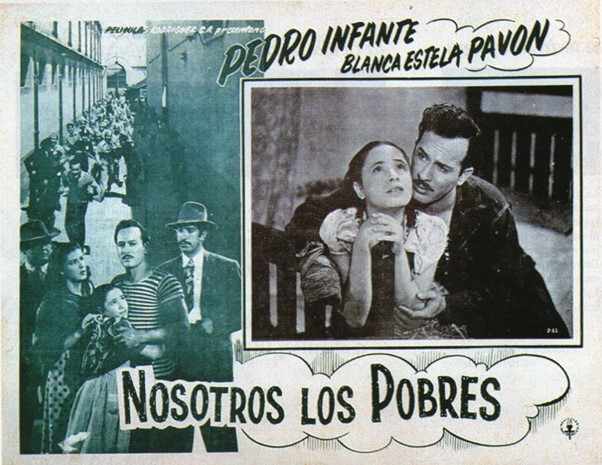

As noted earlier in the interview by Mariano Yberry it might not be safe to enter the Barrio Bravo alone. Chilango Magazine recommends that you “Don’t walk through Tenochtitlán or Jesús Carranza, especially in the stretch between Granaditas and Matamoros. To be clear, only those who know what they are going to enter here. If you arrive via Eje 1 Norte, it is better to enter via Aztecas or Florida; or via Matamoros and Peralvillo, from Reforma.” for safety reasons. I only bring this up here as below you can find an image of tourism at the Bartolome 13 vecindad in Tepito where the movie Chin Chin El Teporocho was filmed.

Chin chin el teporocho (1) is a Mexican drama directed by Gabriel Retes and based on the novel of the same name by Mexican writer Armando Ramírez . It was released on August 15, 1976

- Teporocho : Etymology : Compound of té + por + ocho, literally “tea for eight”. (Mexico) drunkard; lush (Mexico) tramp; vagabond; rolling stone

This movie is another in the “boy from the other side of the tracks” type of romantic tragedy where the plot revolves around Rogelio (Carlos Chávez), a young man from a poor vecindad, who falls in love with Michele (Tina Romero), the daughter of Spanish grocer Don Pepe who forbids their relationship. The story is narrated by Chin Chin (Rogelio), the young teporocho from this Tepito vecindad in Mexico City, who recalls the events of the relationship and his descent into alcoholism and drug addiction.

This archetype ultimately moved onto television.

Casa de Vecindad also features in a 1960’s telenovela (usually just referred to as La Vecindad)

More recently, a vecindad located in the Santa María Nonoalco neighbourhood of Mexico City plays a role in the 2010 Mexican telenovela “Teresa”

Teresa, a beautiful but impoverished woman, blames a lack of money for her sister’s death. She aims to escape poverty using her looks while expecting her lover Mariano, a striving doctor, to fulfill her dreams. While studying on a scholarship, Teresa meets Paulo, a wealthy student. She leaves Mariano for Paulo, aiming to escape poverty. Jealousy, betrayal and revenge ensues.

Telenovelas are melodramas of the highest order.

Aside from cinematic films already mentioned and our brief foray into telenovelas, vecindades have been the setting for national television programs such as El Chavo del 8, and comics such as La Familia Burrón and have even been the inspiration for names of musical groups such as Maldita Vecindad and Los Hijos del Quinto Patio. (more on these in a bit)

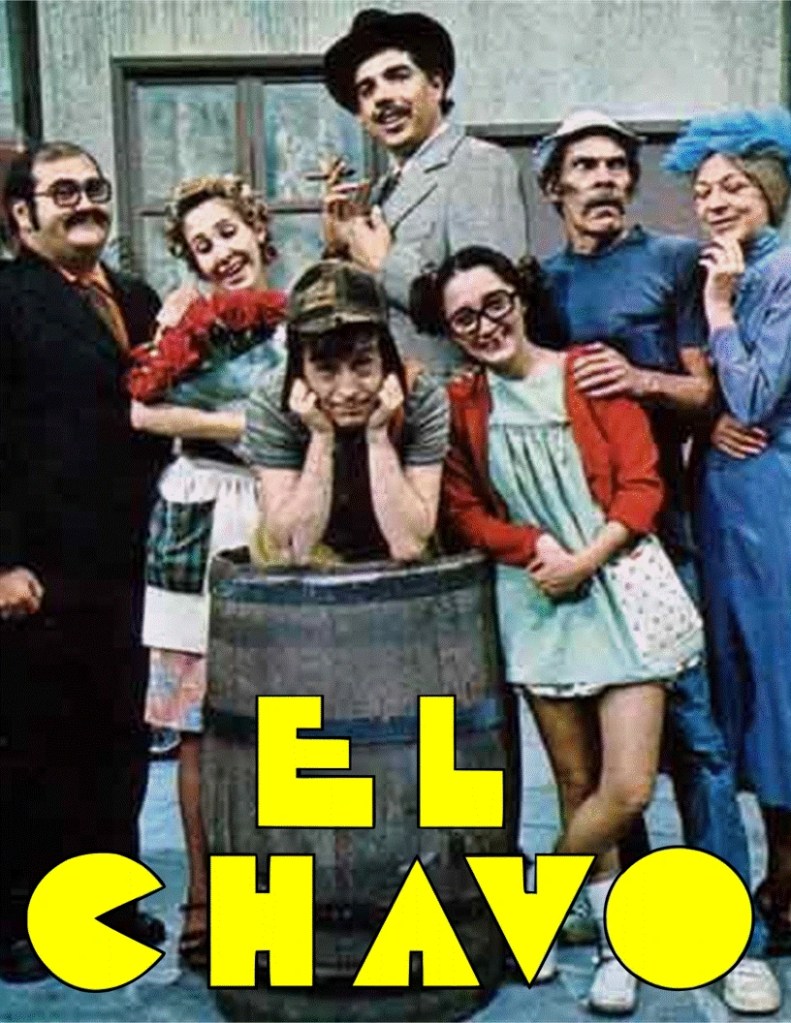

El Chavo del Ocho

This show revolves around the misadventures of a poor, homeless, fumbling bumbling “boy” and his friends in their humble vecindad, El Chavo del Ocho is a Mexican television sitcom series created by Roberto Gómez Bolaños (Chespirito) and produced by Televisa. It premiered on February 26, 1973 and ended on January 7, 1980, after 8 seasons and 290 episodes.

This particular vecindad even comes as a Mattel playset.

“El Chavo” (meaning “The Kid” or “The Boy”)

When comic series El Chavo del Ocho (The Kid from the Eight) debuted in 1973, it became an iconic show across Latin America for its portrayal of a prototypical motley crew of vecindad neighbours: the orphaned boy, the stuck-up child and his haughty mother, the gentle old man in charge of the mail, the spooky single woman thirsty for affection “Doña Clotilde” dubbed “La Bruja del 71 (the witch of number 71) by her neighbours.

The vecindades of the Golden Age of cinema, to the extent that they actually existed, are increasingly difficult to find. Buildings previously used as tenements are now being converted into cafes, shops, hotels or middle-income housing, causing the number of these still used as multiple occupancy housing to reduce dramatically

The multifamiliars or the modern equivalent of the vecindades also play a role in modern movies.

The movie González: falsos profetas is a Mexican thriller filmed in Mexico City in 2013. The protagonist González (played by Mexican actor Harold Torres) a lonely, introverted and frustrated 28 year old man whose life is weighed down by the crushing mundanity of it all. He is one of the invisible masses, unemployed, behind on his rent and his credit card payments, and feels guilty that he is unable to send money to his struggling mother. Quietly wandering the streets of the behemoth that is Mexico City, González, in his desperation approaches a fraudulent faith centre, and tries to obtain employment as a pastor. He ends up joining the team of telephone operators at the temple that makes a profit based on faith and makes suffering an extremely lucrative business. This is a film that touches on the topic of religion and the different organizations that are characterized by manipulating people and how some churches operate that defraud the faithful to supposedly save them from their sins and exposes the abuse of churches on their faithful. This is a movie about the character of a man under great pressure and how he rises (or not) to the challenge.

He lives in the multifamiliar Conjunto Urbano Presidente Alemán, the emblem par excellence of Alemánism (1946-1952) in Mexico and which plays a metaphorical role in the movie which hearks back to those years of social rejuvenism in Mexico. Alemán (1) was the first of a new generation of civilian politicians who had not participated in the military campaigns of the Revolution and his state sponsored promotion of industrialisation and infrastructure growth (and its tolerance of official corruption) lead to a new program based on promoting industrialization through import substitution, heavy subsidies of industry, and maintaining low inflation by suppressing real wages. Alemán was viewed as much less sympathetic than his immediate predecessors to the demands of labour and the rural populations of central and southern Mexico which leads us in turn to the parable of González penned in the multifamilar CUPA with his poverty and hopelessness.

- Miguel Alemán Valdés (29 September 1900 – 14 May 1983) was a Mexican politician who served a full term as the President of Mexico from 1946 to 1952, the first civilian president

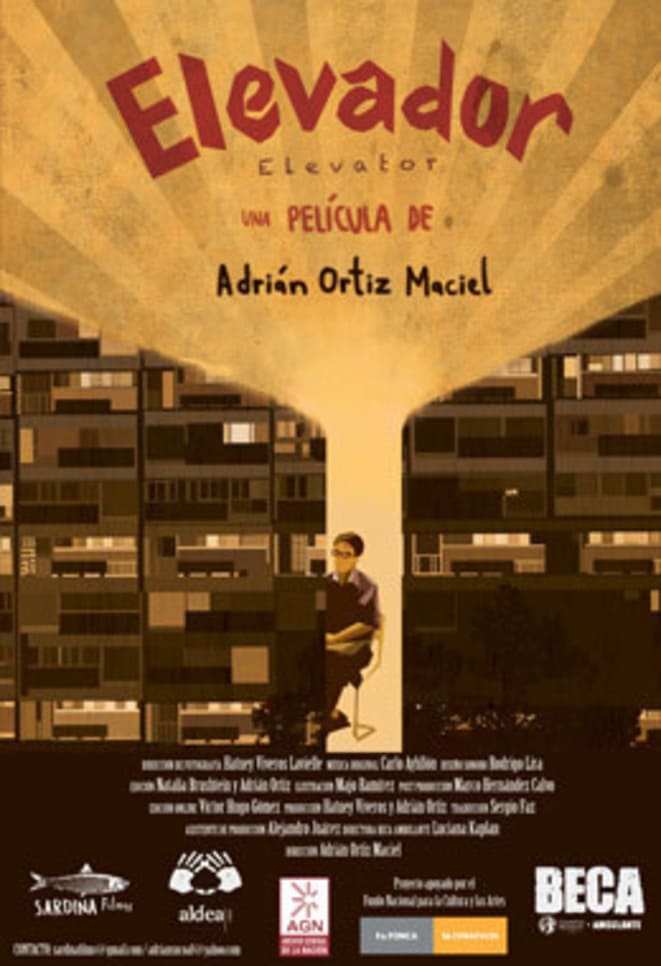

The Multifamiliar Presidente Alemán also plays a part in the first feature film, Elevador (2013), of Adrián Ortiz Maciel. This Mexico City based film focusses on the residents of the President Aleman Urban Housing Complex who are just getting by as life has become a struggle since federal support was withdrawn. The elevators of the housing complex become windows through which we can observe the daily interactions and habits in a microcosm of metropolitan existence and the elevator operators themselves, much like a good bartender or hairdresser, are spectators, guardians and confidants of those living in the building. They are the ones who know the living history of the buildings. The plot of the movie centres on three characters who become trapped in an elevator, triggering a series of intense psychological events that reveal their true personalities and dark secrets.

Comics

Life in the halls and patio of the vecindad

La Familia Burrón (The Burron Family) was created in 1948 by Gabriel Vargas. During its more than 60 years of publication, from 1948 until 2009, it published 500,000 copies, making it one of the longest running publications in the world. The cartoon follows the adventures of a lower-class Mexico City family with the surname Burrón (presumably a word play on the word “burro” which literally means donkey, but is widely used in Mexico as slang for dunce) it may possibly reference the use of “albures” the art of double entendres.

One of the main characteristics of The Burrón Family is its excessive use of slang, contractions, or invented words in almost every dialogue, creating a particular and original invented language that is unique in the world of comics. La Familia Burron is considered one of the most representative comics of Mexican popular culture of all times. It is often cited as a social chronicle of the decades from the 1950s to 1970s.

Gabriel Vargas has been recognized and praised for the amusing use of language in Burron’s comics. Using a unique combination of slang, popular expressions, Prehispanic terms, colloquial and contracted or even invented words, all mixed together, Vargas created a unique language in which basically every single common word of our language has a strange and unusual equivalent in the Burron’s universe. Even the minimal and most insignificant details are described with this needlessly complex and fun invented language. For example, the home of the family is placed in Mexico City, but in a fictitious location in “chorrocientos chochenta y chocho, Callejón del Cuajo “. The number itself has no meaning in Spanish – it is a word play using many Ch phonemes evoking large quantities (chorrocientos is a juxtaposition of “chorro” which means “lots” and “cientos” which means “hundreds”) and a variation of the number 88 (ochenta y ocho). So, basically the family lives somewhere in “many hundreds plus 88 Rennet Alley”.

Tis same plasticity of language is used for parts of the body. For example, Vargas often used the expression “los de apipizca” instead of just saying “eyes”. Apipizca is really an obscure reference to a migratory water bird whose eyes at first sight have the appearance of being irritated, using the original Nahuatl name of that bird, “apipixca”.

For their unusual use of the language, La Familia Burrón has been the object of anthropological studies, essays and dissertations by several universities and language academies around the world.

When I’m trying to pick up another language I like to start with children’s books and comics as a resource to begin with. This particular comic and its looseness with the lengua española is probably not a great one to start with I guess.

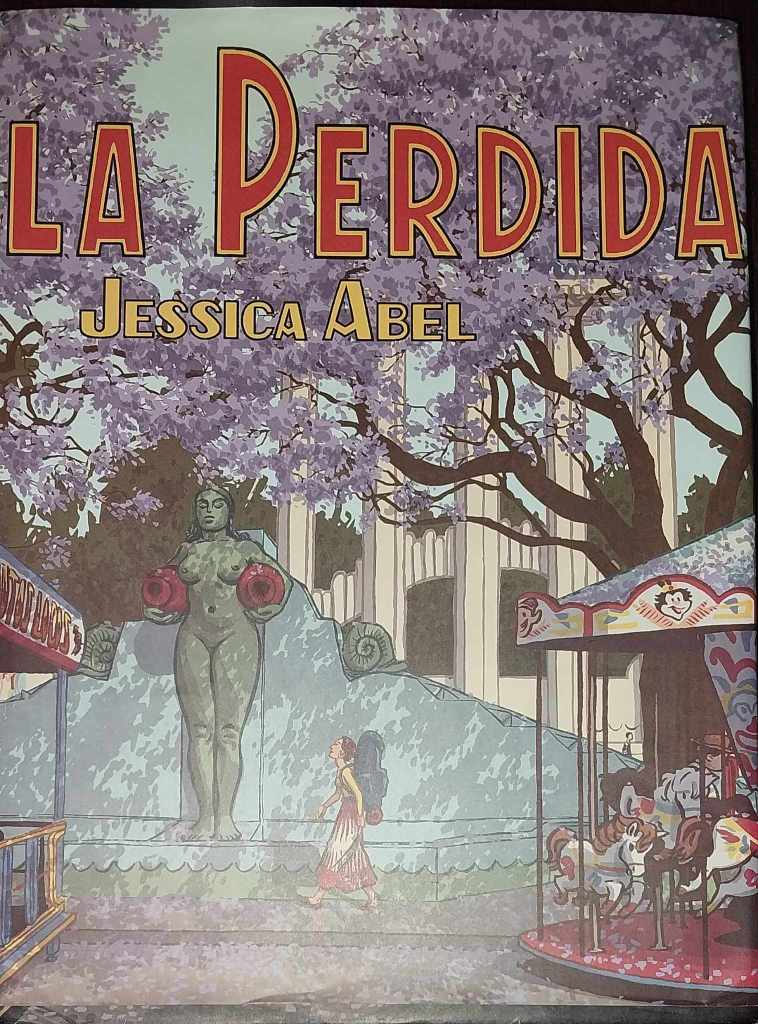

Life in a vecindad also plays a key role in Jessica Abel’s graphic novel “La Perdida”. Jessica travels to Mexico City and ends up moving into a vecindad as it is the only place she can afford. She soon finds herself trapped in the building, surrounded by betrayal and caught up in a kidnapping scheme.

Vecindades in music

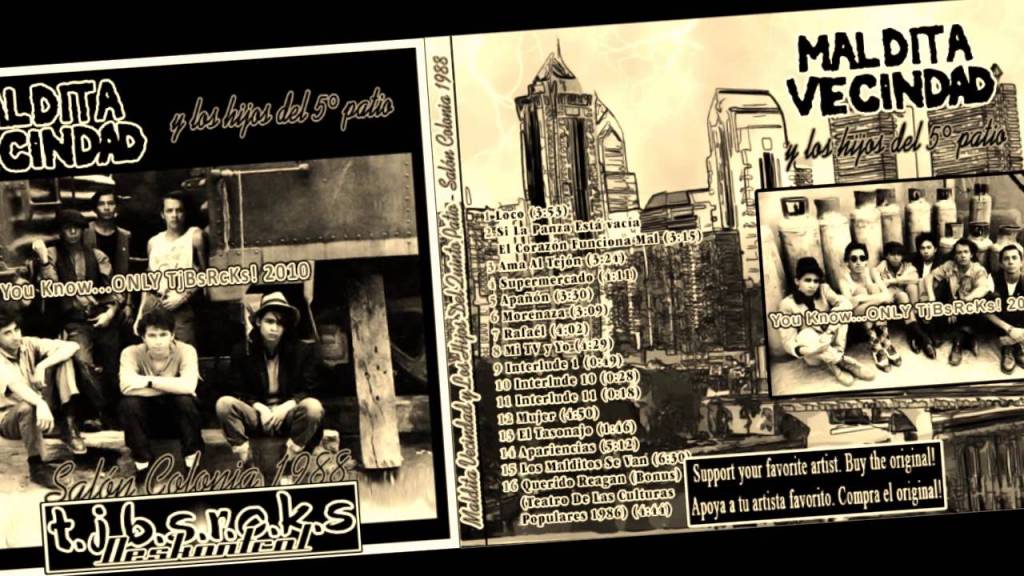

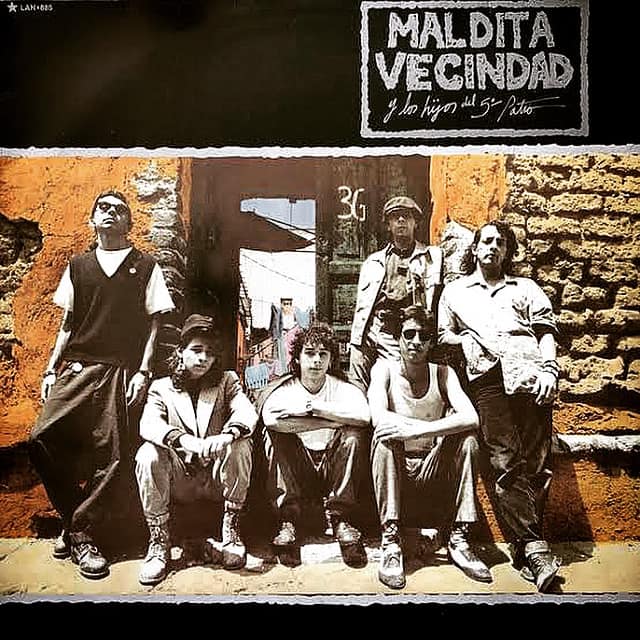

In accordance with the spirit of the vecindades, the Mexican ska band, Maldita Vecindad and Los Hijos del Quinto Patio, took the name of these spaces with the aim of narrating the experiences of a lower class that faced various everyday situations.

They first made an impact with Mojado, Un poco de sangre, Cocodrilo, Pachuco and Un gran circo, songs that narrate the problems, adventures, and beauty of a society anxious to improve its economic status. Their wardrobe has incorporated elements of the pachuco, an archetypical character represented by Tin Tán in Mexican cinema.

In an interview in early 1985, vocalist Rolando Ortega, better known as “Roco,” explained that they took the name Maldita Vecindad because vecindades are a concept of “Mexicanness” with an urban image.

“Suddenly what we return to as Mexican is what we live: the street, the houses, the neighbourhoods, the vecindad is an already urban Mexican image,” he said.

The name “and the children of the fifth patio” has an interesting history. There’s a Mexican movie from 1950, called “The Fifth Patio” due to it narrating the history of very poor families living in a fifth patio in a vecindad in Mexico City Downtown. In the twentieth century there was a vecindad located in the Santa María La Ribera suburb, the front door of which reminded a lot of the front door of that movie’s vecindad, and people in the neighbourhood started to call that vecindad “The Fifth Patio”.

Most of the band members were born and raised in that vecindad, in Santa María La Ribera, Mexico City.

While the band Los Hijos del Quinto Patio took it up as a tribute to Luis Arcaráz for the song “Por vivir en quinta patio” and also “because we have a lot of mix of genres of Mexican popular music we wanted to see that in the name that could be glimpsed.” , “Roco” recounted at the beginning of the band’s musical career in 1985, in information from the official La Maldita Vecindad channel on YouTube.

The song “Por vivir en quinta patio” describes a relationship of rejection of a love for not having the economic solvency that the other person would like and for living in a vecindad.

Por vivir en quinto patio : Because you live in the fifth courtyard

desprecias mis besos : you despise my kisses,

un cariño verdadero : a true affection

sin mentiras ni maldad. : without lies or evil.

El amor cuando es sincero : Love when it is sincere

se encuentra lo mismo : is found

en las torres de un castillo : in the towers of a castle

que en mi humilde vecindad. : as well as in my humble neighborhood.

Nada me importa que critiquen : I don’t care if they criticize

la humildad de mi cariño : the humility of my affection;

el dinero no es la vida : money is not life,

es tan solo vanidad : It’s just vanity.

Y aunque ahora no me quiere : And although now he doesn’t love me,

yo sé que algún día : I know some day

me dará con su cariño : he will give me his love

toda la felicidad. : all the happiness.

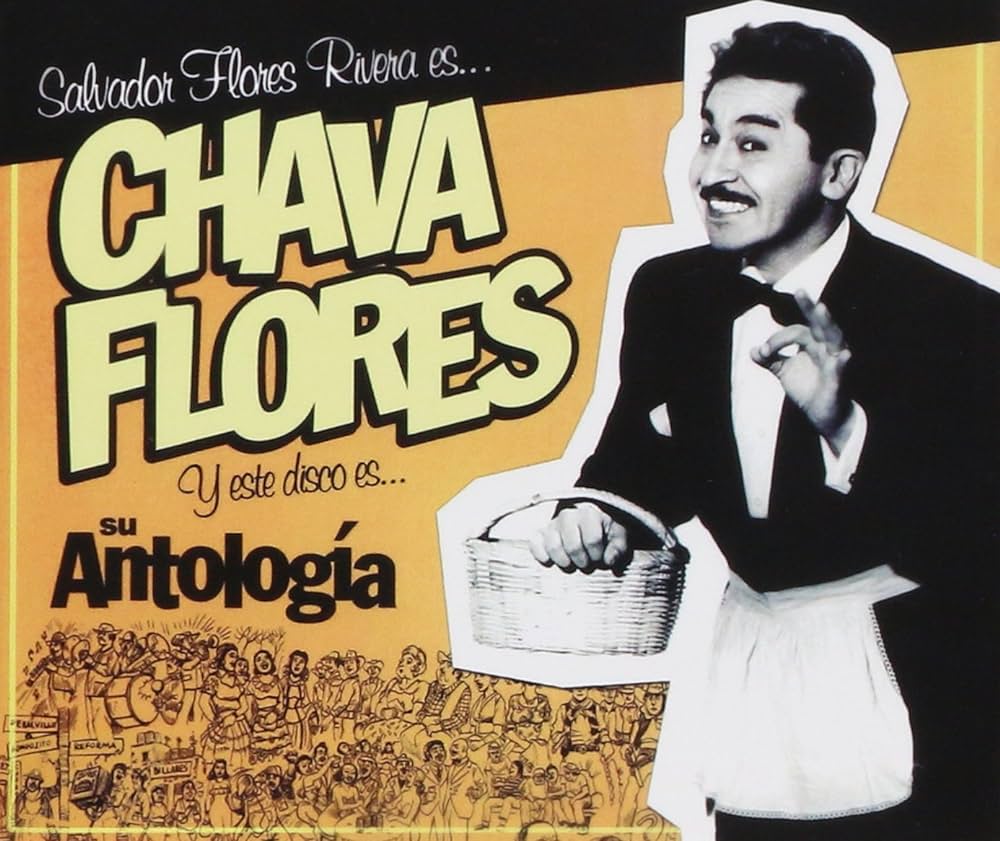

Other songs that refer to these homes are Boda de Vecindad , Mi linda vecindad and Hogar dulce corazón by Salvador “Chava” Flores.

Salvador Flores Rivera, also known as Chava Flores, was a Mexican composer and singer of popular and folkloric music. His songs often described the lives of Mexico City’s ordinary people

Boda de Vecindad

Se casó Tacho con Tencha la del ocho : Tacho married Tencha from number eight,

Del uno hasta el veintiocho pusieron un festón : From the first to the twenty-eighth they put up a festoon;

Engalanaron la vecindad entera : They decorated the entire vecindad,

Pachita la portera, cobró su comisión : Pachita, the doorwomman/concierge, collected her commission.

El patio mugre ya no era basurero : The dirty patio was no longer a garbage dump

Quitaron tendederos y ropa de asolear : They removed clotheslines and the clothes hung up to dry

La pulquería Las Glorias de Modesta : The pulquería Las Glorias de Modesta

Cedió flamante orquesta pa’que fuera a tocar : Provided a brand new orchestra to play.

Tencha lució su vestido chillante : Tencha wore her bright dress

Que de charmés le mercó a don Abraham : That she bought on credit from Don Abraham

A Revival of Sorts

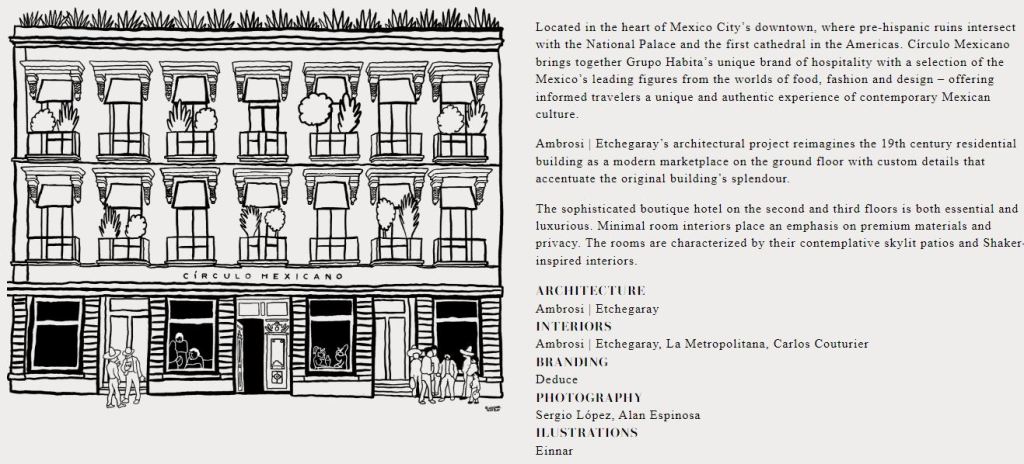

Things may have changed in the CDMX (the Mexican capital), and are changing still. The vecindades of Golden Age Mexican cinema — to the extent they ever truly existed — are harder to find. Buildings previously used as vecindades are now being converted to cafes, shops, hotels or middle-income housing, making the number still used as multiple-occupancy tenements shrink drastically.

A vecindad refurbished into a hotel

A recent photography project from the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History found evidence of more than 480 vecindades in the city core in 1925. It’s difficult to find estimates of how many survive today as housing tenements, though Castillo estimates that the number may be a few as 100. These surviving tenements, meanwhile, are often in poor condition and can have problems with crime associated with the drug trade.

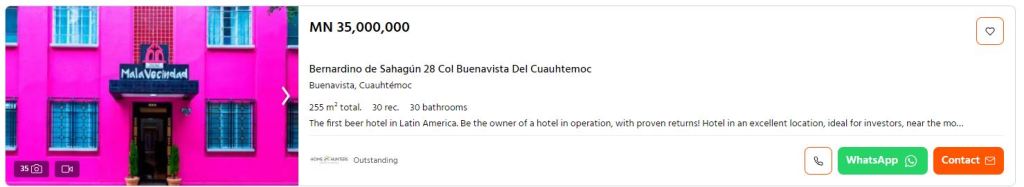

Others are being rehabilitated into the 21st Century

At Bernardino de Sahagún, number 28, in the Colonia Buenavista Del Cuauhtemoc in the Ciudad de México you can find one of a few “Mala Vecindades” in the CDMX. This one is a beer garden hotel (and is touted to be “the first in Latin America”).

Apparently its for sale if you’re interested.

At 35 million pesos that’s about 2,869,125 Australian Dollars (as of 27th June 2024)

This establishment is based on second chances, on rescuing from oblivion and abandonment and giving new life to the old. The furniture, like the building itself, is recycled. The owners have worked with upholsterers and carpenters to reuse existing furniture, as well as local blacksmiths to recover the property’s ironwork and classic art deco decorations to maintain and reproduce the same aesthetics of the 1940s, when the hotel was at its most splendorous.

10 minutes away at República del Ecuador 10, Lagunilla, Centro Área 2, Cuauhtémoc, 06010 you can find another Mala Vecindad.

Grupo Inmense has joined with the initiative of the CDMX government together with the Cuauhtémoc mayor’s office to begin the recovery of the spaces in the historic center with the remodeling of this iconic1930’s property in Ecuador 10, they hope to create a new boom for the area and contribute to preserving the traditions of Mexico.

A vecindad revived in an urban context

Mar Mediterraneo 34, Tacuba, Mexico City, Mexico.

Architect Inca Hernandez Atelier

Mar Mediterraneo 34 stands as a testament to the adaptive reuse of historical architecture, reemploying the principles of Casas de Vecindad in the traditional way. Situated in Tacuba, a neighbourhood rich in cultural heritage, the project breathes new life into a 1910 eclectic French-style house that was all but abandoned.

The building is made up of three levels and seven apartments

Built in 1910 through an eclectic French style belonging to the Porfiriato era, it currently holds historical value by the National Institute of Fine Arts and the National Institute of Anthropology and History.

They have not disappeared though.

Property for sale in Naucalpan, State of Mexico divided into profitable neighborhood-type spaces.

Ideal property for investment since it generates monthly income of approximately $28,000 pesos ($336,000 pesos annually), representing an annual return of 8.4% on the investment.

The property has the following characteristics:

355m2 of land

355m2 of construction

4 profitable spaces with 3 rooms each, 3 of them with a full bathroom and 1 with a half bathroom, sink (current rent $3,400 monthly each)

6 profitable spaces with 2 rooms each, 2 of them with a full bathroom and 4 with a half bathroom, sink (current rent $2,400 monthly each)

Roof for laying

20,000 liter cistern

2 water tanks

Currently water is included in the cost of rent, and additionally each person pays their gas and electricity consumption (independent meters)

Many are nonetheless undergoing restoration, both by the government and their own residents.

Restoring History

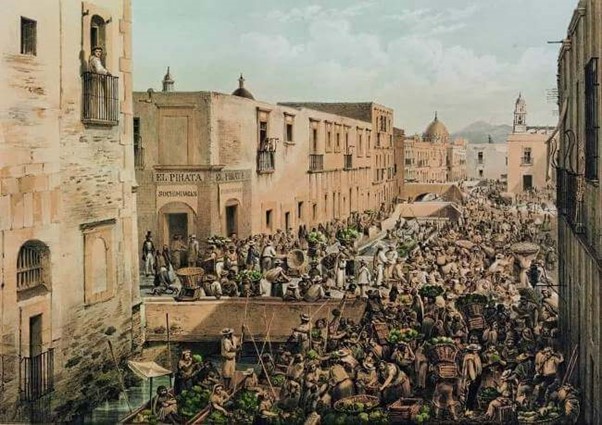

In CDMX there is a domicile built in the 16th century that is still standing.

It is a one-story house built in the 16th century.

Located at C. Manzanares 25 (number 25 Manzanares Street), in the historic colonia (neighbourhood) of La Merced, among all the buildings to be found in the Mexican capital it is officially considered the oldest of such.

This neighborhood was probably the first stone of the foundation of Tenochtitlán. It is believed that what is today Mesones Street, in the Plaza de la Aguilita, is exactly where the Mexica found the eagle perched on a cactus, devouring the snake. This would be the first lake territory that the Mexica occupied, known as Zoquipan or Teopan.

Here was also found the neighbourhood called Temazcaltitlan, site of temazcales. It is known that in this neighbourhood various female deities were worshiped, such as Mayahuel, Coatlicue, Ayopechtli or Toci. The temazcal, in addition to being used for bathing, was used in rituals to to purify, cleanse and reconnect with oneself and nature. (I’ll need to do a Post on the temazcal at some point)

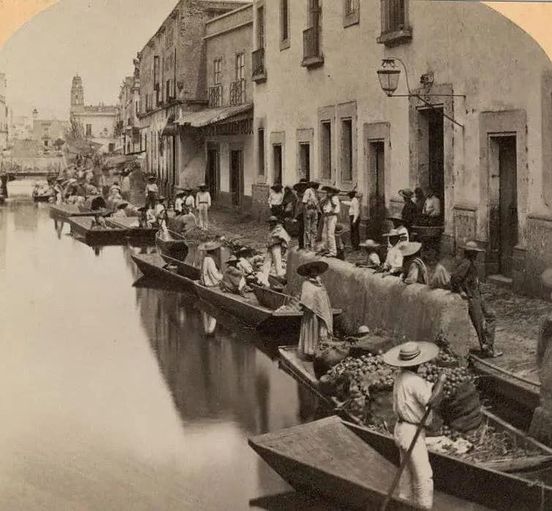

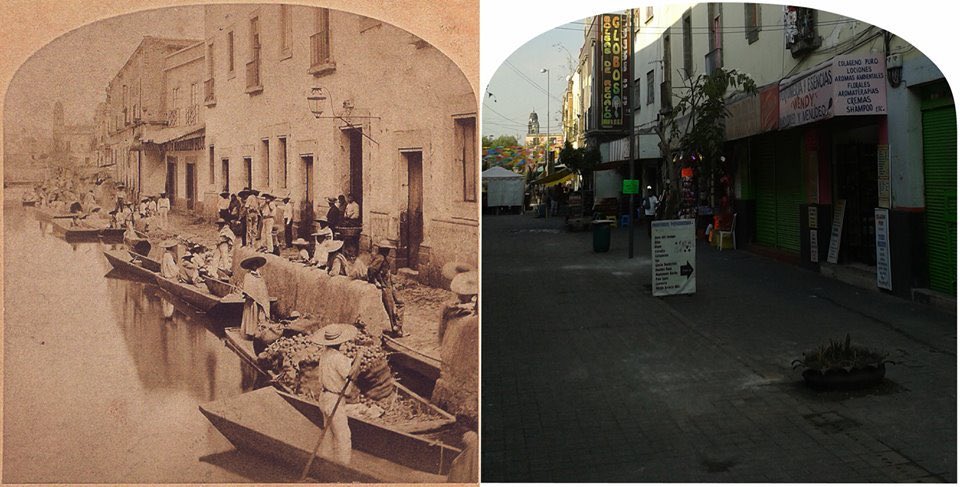

“La calle de Roldán” in Mexico (1855)

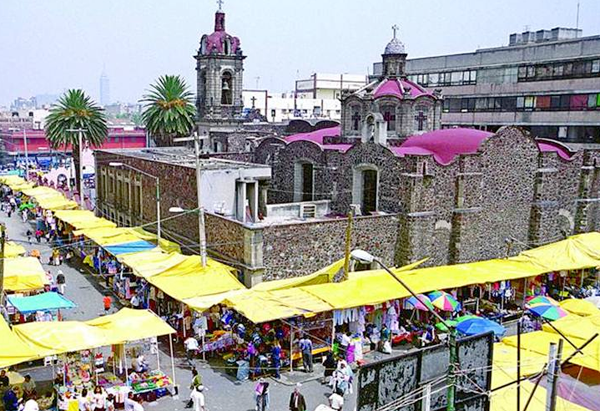

According to historians, the founding of this neighbourhood dates back to the year 1325 and it receives its name from the Former Convent of Nuestra Señora de la Merced.

With the arrival of the Spanish the area changed, churches and convents were built. With the arrival of the Convent of La Merced in 1594, commercial activity began to take place.

The proximity to the Roldán pier meant that all the products would arrive in the area. Almost the entire neighbourhood was a market, the streets specialized in a specific product. (Biar 2021)

Trajineras arrived in these channels with various products from other places such as Xochimilco, Tláhuac, Chalco and Texcoco and here circulated the local merchants who were going to sell in the neighbourhood..

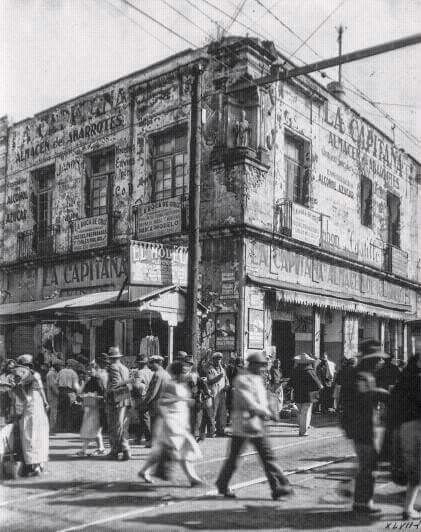

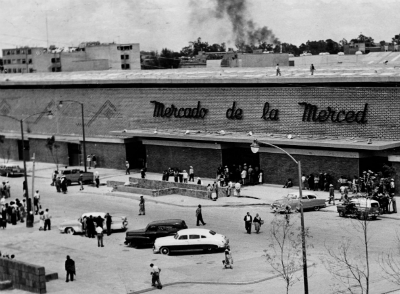

Merced Market – Historic Center Trust

The Merced market takes its name from the neighbourhood and was the first open-air market, or as Chilangos know it: the first tianguis (1). In 1860 it was decided to give the market a covered space and what we know today as the famous Mercado de la Merced was built. With the Reform laws it was decided to demolish the old temple of La Merced, but the convent was saved.

- Tianquiztli (in Nahuatl)

This is what the oldest house in CDMX looks like .

25 Manzanares Street is believed to have been constructed sometime between 1570 and 1600.

This house dates back to the conquest and shows the fusion of two cultures. According to researchers, its foundations are made of tezontle and its walls are made of adobe and stone in the manner of the houses of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. In its construction plan there is the classic indigenous construction structure, with the patio in the centre, although the frames of its doors and windows are made with quarry-stone lintels, which is a Spanish element. The thick rock around the base of the building’s walls, and the building materials — this mix of stones, volcanic rock and adobe — show Aztec influences on the Spanish colonial style so the building merged the two architectures of these two cultures.

Tezontle is a porous, highly oxidized, volcanic rock used extensively in construction in Mexico. It can be mixed with concrete to form lightweight concrete blocks, or mixed with cement to create stucco finishes. Many colonial buildings in Mexico use the reddish cut tezontle on their facades. Tezontle is a common construction material in the Historic Centre of Mexico City as the relatively light-weight stone helps impede a building from sinking into the unstable lake bed on which Mexico City was built.

For more than four centuries, it was a vecindad, housing families in its dozen rooms overlooking a central patio.

There were plans to tear the building down before the city realized how old it was — now, instead, it’s undergoing a restoration meant to protect the structure. With more than 400 years of history, this house has survived floods, earthquakes, epidemics and now, modernity.

Starting in 2010, different architectural studies were carried out on it and due to its age, the Historic Centre Trust decided to preserve it and repurpose it as a resource dedicated to the community.

In 2016, the National Institute of Anthropology (INAH) took on the task of restoring it and in December 2018 it opened its doors as a Cultural Centre, the Centro Cultural Manzanares 25.

In its central patio it has a stone basin that serves as a pool. Its roof has drains and its doors measure half a meter wide. During its restoration, its wooden ceilings were renewed, the stones of the patio being rearranged and the walls covered with a layer of plaster.

But while the building will survive, its long history as a site of affordable housing and vibrant community life may still come to an end. Eighty-two-year-old Rosa Maria Ubaldo Lopez was born in Manzanares 25 in 1938 and lived there well into adulthood, raising eight of her 10 children there. She’s happy about the restoration, she says, wistfully remembering her childhood in the vecindad.

“It was pretty there,” she said. “We all knew each other.”

The renovation of Manzanares 25, in the Merced neighborhood of Mexico City. It is the city’s only standing home from the 16th century, according to the Historic Downtown Mexico City Trust. The house sits on a corner, has one level, a courtyard and 12 rooms. In recent years, it had gone into disuse, with some of its roofs caving in, and shrubs and weeds covering its floors and walls.

Florentino Canales Vargas, was born in one of the rooms on Nov. 2, 1938.

Canales remembers salesmen visiting the house to sell things such as firewood or fish to his parents and the other families that lived here, he said. One salesman would sell candy to children for one cent, and would sing a song to every child who bought one.

Canales lived with his mother and father in one room, as was the case for most families that lived in the house. It is believed the house was originally owned by a salesman who built one room in the late 1500s and added rooms for his children when they grew up and had their own families,

Is it the oldest though?

Ignacio Lanzagorta, a Mexico City urban anthropologist who studies the history of public spaces, is not convinced. Lanzagorta is skeptical of this because the area had been prone to floods (until nearby canals were drained), and because its architecture resembles that of newer Spanish homes from later eras.

Manzanares Street, which at the beginning of the 20th century was the royal irrigation canal. Part of la Colonia Merced.

The decline of these buildings and of the city’s cultural heritage is an ongoing problem.

In a May 10, 2024 an Editorial in Entre Ladrillos (Between Bricks) by Aura Moreno, Adriana Flores, Fernando Arauz, Lorenza García, Oswaldo Guevera and Roció López (a group of journalist architects) called Vecindades en decadencia: ¿si el gobierno no las cuida, por qué sus habitantes no pueden intervenir? (Vecindades in decline: if the government does not take care of them, why can’t its inhabitants intervene?) a conundrum was presented.

Some of the vecindades in the CDMX are collapsing and others are sinking, and no one is doing anything about the decay of these national treasures. In the article Entre Ladrillos analyzes the causes and asks “If the government doesn’t take care of them, why can’t its inhabitants intervene?”

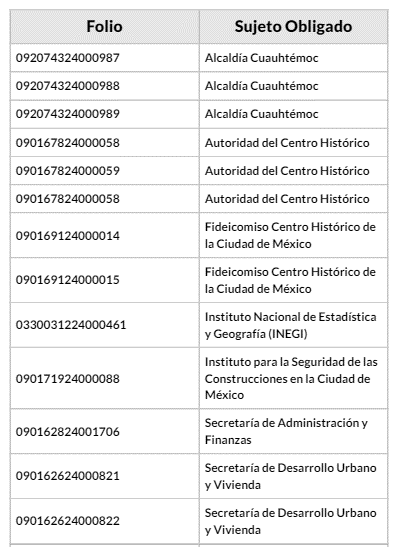

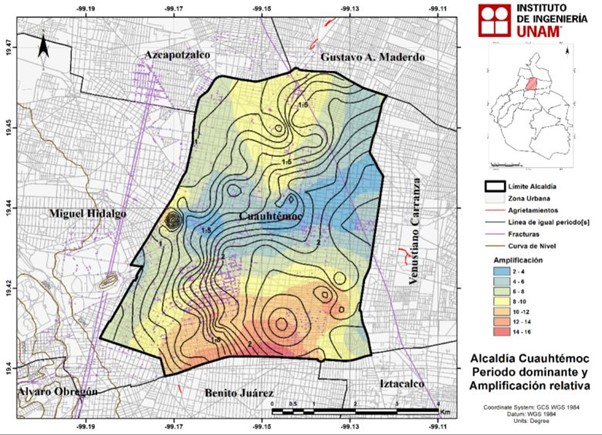

According to the UNAM Engineering Institute, factors such as water extraction (the lakes have been drained continuously since the arrival of the Spanish 500 years ago) (Poreh etal 2021) and earthquakes have generated subsidence and settlements in the historic center. The earthquake of 1985 created a tremendous amount of destruction and the 2017 temblors have only exacerbated the problems. Studies show that some areas of the city sink at annual rates of up to 45cm (O’Hanlon 2021) although the September 2017 earthquakes were not as drastic they did induced significant sudden settlements, with variations of between 1.2 and 5.0cm in different areas. (Solano-Rojas etal 2024). These issues can be alleviated somewhat, as according to architect Everardo Vázquez “Through a geotechnical correction procedure that involves sub-digging and filling the soil, historical buildings such as the Metropolitan Cathedral have been rescued, an effort that to date has cost 5 years of work and more than 200 million pesos”. The same amount of effort and money however has not been put into protecting and resroring vecindades regardless of their historical importance.

“The subsoil is muddy, it has aquifers and pre-Hispanic temples buried in unknown areas, which is why the sinking of each area of the colonia is unique,” explains architect Everardo Vázquez.

Since the 2017 earthquakes the authorities have not returned to previously damaged properties particularly in the poorer neighbourhoods. The residents of this areas have hesitated to have authorities inspect these properties for repairs for fear that they will be evacuated from their homes and other people will take over their assets without permission. They also cannot afford to fund the repairs themselves. This is exactly the same problem residents had in the early 1900’s. The are amongst the poorest of the city’s inhabitants so are unable to fund the repairs themselves and they fear attracting government intervention as it may result in expulsion from their homes. The cycle of repressing the poor continues.

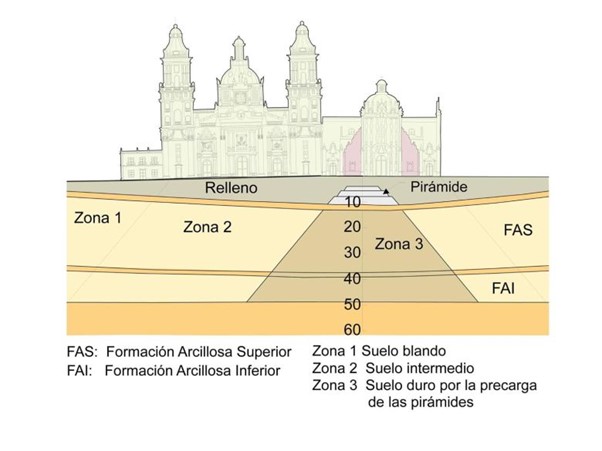

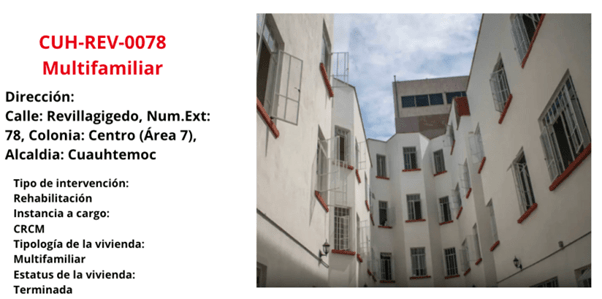

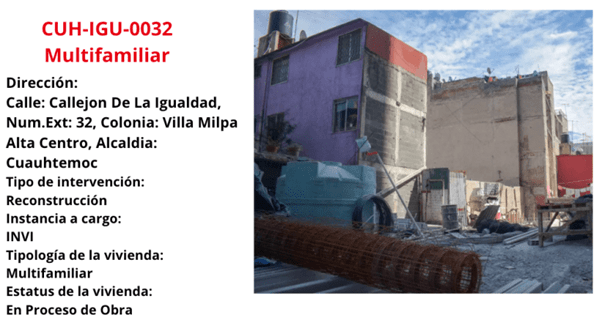

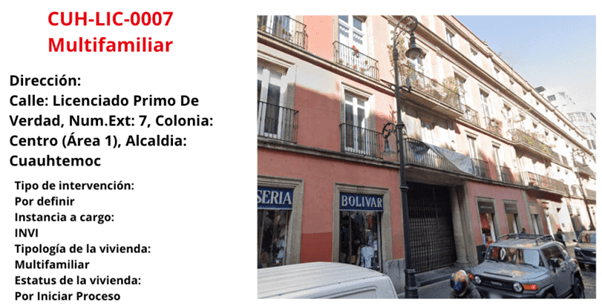

After the 2017 earthquake, only five multi-family buildings in the historic center were integrated into the program for the reconstruction of CDMX. The following images are of these 5 buildings…..

The last registered building, the multifamila building with code CUH-LIC-0007, is at high risk of collapse, so it must be evacuated and restored as soon as possible. The reconstruction program provided five rent supports so that tenants could vacate the building.

Seven years after the earthquake, its restoration has not yet begun, which must be authorized and supervised by the INBA and the INAH. This is primarily due to the owners’ lack of resources to repair the damage.

Entre Ladrillos asked “How many homes are in this same condition?” They don’t know, as ultimately they couldn’t gain access to that information…

According to the the Federal Law on monuments and archaeological zones, the owners of the monuments (of which vecindades are categorised) must restore them, after first receiving authorization from the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). This can be problematic, as with regulations in my own country, there are approved building methods, materials and processes to be adhered to when renovating or repairing historical monuments (even down to the colour of the paint that must be used)

So how does the INAH resolve these applications?

The response from the institute takes 20 business days for properties within CDMX , and when the authority does not respond to the request, it is to be understood that it has been rejected. Once you have submitted your application the INAH requires the following:

- Adherence to institutional regulations

- Technical quality of the analysis of the deterioration of the work and the intervention proposal

- Academic and professional profile of the responsible restaurador (restorer) and participants

Entre Ladrillos notes that the lack of government support to address the deterioration of housing in the historic centre of Mexico City is alarming with the standard response being….

“It is not our concern”

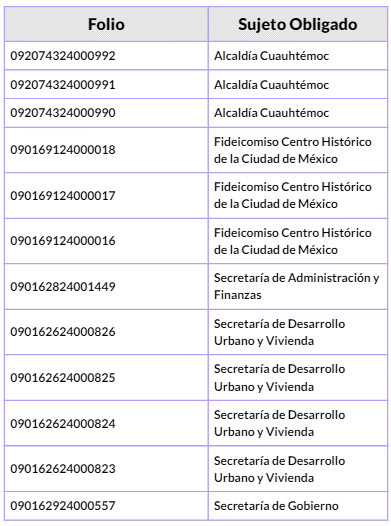

So, to learn more about government involvement in vecindades, they turned to the Transparency Platform (PNT) and made six different requests which they addressed to eight different governing bodies:

- INEGI : Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (National Institute of Statistics and Geography)

- INBA : Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes

- Alcaldía Cuauthémoc (sic) – Cuauhtémoc Mayor’s Office