The prehispanic biscuit known as a tlaxcal (also tlascal : plural tlaxacales) has the same etymological root as the tortilla.

The name of the region known as Tlaxcala is derived from the Classical Nahuatl Tlaxcallān, from tlaxcalli (“tortilla”) + -tlān (place of), although some historians note that the toponym (1) for Tlaxcala comes from another Nahuatl word texcalli which meant ‘stone, rock, crag (2)’ and which does accurately describe the topography of the area (3).

- a place name, especially one derived from a topographical feature (relating to the arrangement or accurate representation of the physical features of an area)

- crag – a steep or rugged cliff or rock face.

- The western part of the state lies on the central plateau of Mexico while the east is dominated by the Sierra Madre Oriental, home of the 4,461 metre La Malinche volcano. Most of the state is rugged terrain dominated by ridges and deep valleys, along with protruding igneous rock formations.

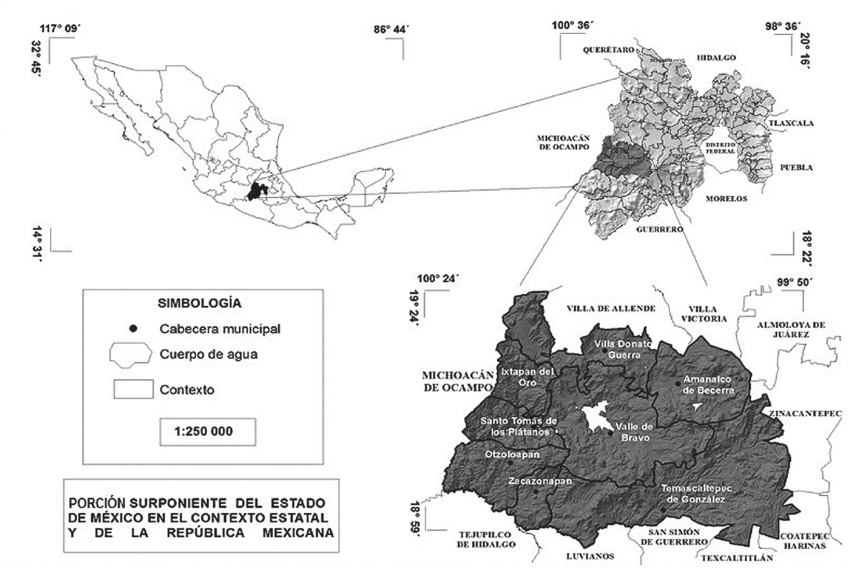

Tlaxcala, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Tlaxcala, is located in east-central Mexico, in the altiplano region, with the eastern portion dominated by the Sierra Madre Oriental.

The state shares borders with Puebla to the north, east, and south, México to the west, and Hidalgo to the northwest.

Regardless of it specific etymology the Aztec name glyph for Tlaxcala includes both these elements, showing a hand making tortillas between two mountains.

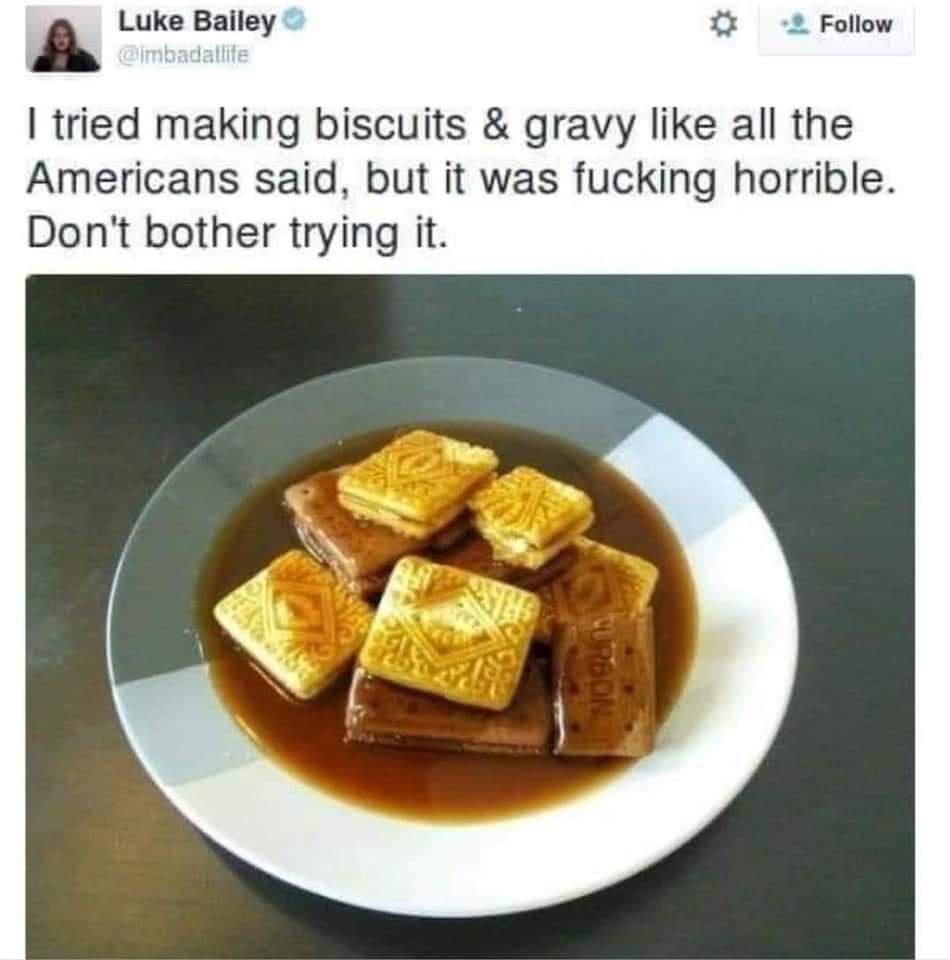

Now, when I say “biscuit” I feel I need to explain myself, as being Australian, biscuit can have confusing connotations when we come to North America.

What I know (as a chef) to be a “biscuit” in el Otro Lado (Unidos Estados Americanos – the U.S.A) is what we would call a “scone” in Australia (and jolly old England too) but the gringos (just to differentiate from “Americans” – which Mexicans also happen to be) eat them in a savoury manner with the addition of gravy (1). We tend to eat our scones (pretty much exactly the same thing as a “biscuit”) with strawberry jam and a dollop of cream.

- a thick sauce made from the drippings of cooked pork sausage, flour, milk, and often (but not always) bits of sausage, bacon, ground beef, or other meat.

In Australia this (image below) is a biscuit (and a plain one at that)

So…..when I visualise “biscuits and gravy” this is what my mind conjures

The tlaxcal however is none of these things. (Possibly) originating in Tlaxcala (and also possibly being the original incarnation of a tortilla) the un-nixtamalised biscuits can also be found in Puebla, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Morelos and the Surponiente regions.

These biscuits can be made from either fresh or dried corn kernels and they are also a part of México’s cultural heritage which is potentially in danger of extinction due to the ever growing range of mass produced sweets and biscuits becoming ever more readily available.

Typically triangular in shape the prehispanic version would have been made from ground corn, a pinch of tequesquite (1) and enough water (if using dried maize) to make a thick dough that would have been cooked on a comal until ready.

- Tequesquite and for a little more history….Esquites, Tequesquite and a Witches Curse.

Some varieties are rounded in shape and are marked by the cook pressing her fingers into the surface of the biscuit

GORDITAS DE LA VILLA ¡EXQUISITAS!

(Mexico Desconocido)

These biscuits also had a sacred function in that they are (in some areas) integral to the ofrendas for Dia de Muertos.

The interesting thing to me about these biscuits is that they are one of the very few recipes for using corn that has not first been through the process of nixtamalisation. Briefly (1), nixtamalisation is the process of cooking corn kernels in an alkaline liquid (2) which removes the outer skin (or pericarp) of the corn kernel. The process releases various gums and colloids otherwise trapped in the corn and allows it to be ground into a sticky dough (called masa) which can be formed into tortillas (3) (it also releases nutritional content that also would be locked into the kernel and otherwise unavailable for absorption within the human gastrointestinal tract)

- Nixtamal

- made so by the addition of calcium hydroxide (or slaked lime) or wood ashes

- See also Masa, Tortillas and Vitamin T for other uses of nixtamalised corn dough

If you simply grind dried corn kernels without first nixtamalising them you get a product which I know as polenta and one that is entirely unsuitable for making tortillas.

These biscuits are made a little differently today. You still use corn but you would more likely use baking soda instead of tequesquite, and other ingredients not available prehispanically such as piloncillo (sugar made from unrefined sugar cane juice) or white sugar and spices such as cinnamon and vanilla (which might have been available in some areas as it does come from Mexico) which would then be ground with the corn on the metate, and you might hydrate the dough with milk, cream and/or eggs rather than just water.

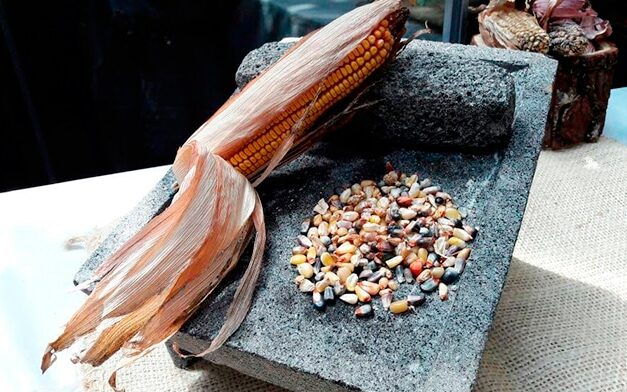

The metate is a very prehispanic kitchen tool (which the woman of the house would have spent many hours labouring over every day to grind the corn needed to make the days tortillas)

Dried corn Tlaxcales

Ingredients

- Dried corn cobs

- Piloncillo

- pinch of tequesquite (or using baking soda – or omit entirely)

- cinnamon

- Egg

- Milk

La Doña from Recetas de La Doña give a recipe from La Mixteca Poblana (1) using dried blue corn. She uses 8 kilos of corn to which is added 1 kilo of sugar. The corn kernels are shelled from the cob and covered in water to be soaked for 2 hours before grinding.

- La Mixteca is a cultural, economic and political region in Western Oaxaca and neighbouring portions of Puebla, Guerrero in south-central Mexico, which refers to the home of the Mixtec people. Poblana means “of, or relating to Puebla”

Method

Once the corncob has been shelled, it is ground until it becomes a fine flour; the consistency of pinole can be used as a reference.

The piloncillo is then ground and added to the flour and mixed.

Milk and egg are then added in small quantities to create a dough. If desired, the liquids and piloncillo can be replaced with water and honey, which will make the recipe even more traditional.

Finally, the gorditas (1) are formed into triangular shapes. Care must be taken to ensure that they do not exceed one centimetre in thickness. They are placed on a hot griddle and left to cook until they can be separated, then they are turned over. This exercise is carried out several times to ensure internal cooking.

- ‘gordita” refers to a small chubby or plump thing. It is also a slang term (i.e fatty) for an overweight person

Fresh corn tlaxcales

Ingredients

- 3 elotes tiernos (fresh corn cobs) See **NOTES**

- piloncillo (1/2 to 1 cone)

- egg

- milk

Method

- remove the kernels from the cob and grind in a metate or hand cranked molino (you could also use your molcajete but this will be more time consuming as you’ll have to do it in small batches). You want to make a type of floury paste. It does not have to be completely smooth.

- Grate the piloncillo and grind into the corn dough

- add egg or milk (or both – or even just water) a bit at a time until you have a thick integrated dough. See **NOTES***

- Form the dough into triangle shapes about 1cm thick and cook on the comal until golden brown. You can turn over the tlaxcal once it no longer sticks to the comal. See **NOTES**

**NOTES**

1. try to use starchy corn if you can get it. This is not the same as the yellow sweet corn that is readily available in Australia. Starchy corn is usually used as animal feed. If you can get white corn use this, although I have seen tlaxcales being made with all colours of corn including yellow, red and blue.

3. Instead of using eggs, milk or water as the liquid in the dough you could follow the lead of Ana Narváez who uses guavas as the liquid in the recipe. Grind guavas (she uses 6 guavas to 12 elotes tiernos) and then strain them to remove the seeds and then mix as much of this as you need into the ground corn.

4. It is recommended that you use a clay comal for this as it will add a flavour not available when cooked on a metal hotplate (which is still totally valid to do) and the clay comal will also absorb some of the liquid in the dough giving it a different kind of crust

Nestle has published a similar recipe

Ingredients

- 2 1/2 cups tender white corn

- 1/2 tsp baking soda

- 1 cup sugar

- 1/3 cup melted butter

- 1 egg

- Evaporated milk (about 1/4 cup)

Method

- blend all ingredients to a paste (only add as much of the evaporated milk as is need to make a thick dough)

- melt a little butter in a frying pan and add a heaped tablespoon of the corn mixture

- shape into a triangle shape with your spatula while it is frying and brown on both sides

- serve with a sauce made from 500g of strawberries which have been blended with a can of condensed milk (this kind of reminds me of my scones with jam and cream – kinda)

It is said that Tlaxcales must be cooked on a clay comal and over firewood to acquire their peculiar flavour

A Tlaxcal street vendor

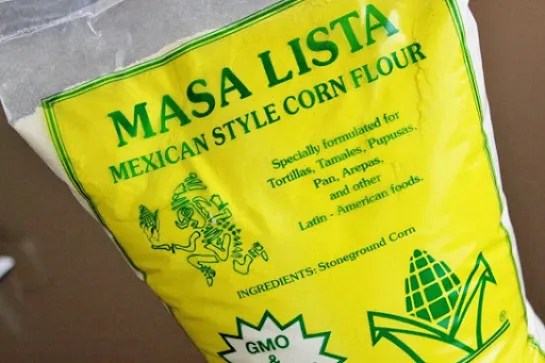

Now I know I did mention earlier that this recipe was made using un-nixtamalised corn but here we have Fernanda Berlai on Gorditas de la Villa ¡EXQUISITAS! giving us a recipe (using what looks to be maseca)

- 2 cups of Harina de maíz nixtamalizado

- 1 cup of sugar (type not noted although the recipe called for azúcar which is typically not how piloncillo is referred to)

- 4 egg yolks

- 2 teaspoons of pork lard

- 1/2 teaspoon vanilla

- 1 teaspoon baking powder

- 1 pinch of salt

- Milk (as needed)

Varieties of harina de maiz nixtamalizado

(and has the benefit of being GMO and glyphosate free)

Corn can be a sticky issue when it comes to health concerns. Figures shown that as much as 92% of corn is genetically engineered (usually to increase crop yield, allow it to tolerate higher concentrations of herbicides and pesticides, or to allow it to grow in unfavourable conditions) and testing has shown that the Maseca brand is highly likely to contain both GMO’s (genetically modified organisms) (1) and glyphosate (a broad spectrum organophosphorus herbicide). Both of these elements are somewhat controversial when it comes to their effects on human health with them being derided as extremely dangerous to human health (by the organic brigade) and as having no proven effects at all (by their manufacturers of course). See References at the bottom for links. In Australia GMO crops cannot be labelled as organic.

- GMO (short for “genetically modified organism”) is a plant, animal or microbe in which one or more changes have been made to the genome, typically using high-tech genetic engineering, in an attempt to alter the characteristics of an organism. Genes can be introduced, enhanced or deleted within a species, across species or even across kingdoms. For thousands of years, humans have used breeding methods to modify organisms. Corn, cattle, and even dogs have been selectively bred over generations to have certain desired traits. Within the last few decades, however, modern advances in biotechnology have allowed scientists to directly modify the DNA of microorganisms, crops, and animals. It is very likely you are eating foods and food products that are made with ingredients that come from GMO crops.

Other varieties of tlaxcales

Toqueres

I have also seen the toqueres of Guerrero called memelas de camagua (camahua) where they are an important part of the ofrenda for dia de muertos.

INGREDIENTES Para elaborar Toqueres Guerrerenses

3 docenas de elotes

1/4 de kilo de manteca

To make toqueres, the corn should be picked when it is not yet fully ripe. Slice the corn and grind it; then add lard and salt to taste. Make thin tortillas and place them on a griddle over low heat until they brown.

Tacachotas (Zacatecas)

Memenshas

I’ve also seen it written as – memanxás, mamanxás, mjenchas, mhemxa, mamasha

Memanxás is an Otomi word meaning tender corn. Which (according to Larousse Cocina) refers to small gorditas made of chickpeas, cinnamon, sugar and anise cooked on a clay griddle, which the locals of San Joaquín in the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro prepare during the All Saints’ Day festivities. In some cases, cheese is added and it is cooked on an anthill stone (piedra de hormiguero)

The piedra de hormiguero

Escuela de Gastronomia Mexicana

68-year-old Luz María Reyna Cortés originally from Francisco I. Madero explains that the piedra de hormiguero is used to gook her gorditas as previously “no había teflón” (there was no teflon) and the stones prevented the bolitas of masa from sticking to the comal. The stones used to cook her gorditas are the small and fine ones found around anthills. Luz María recommends collecting stones from anthills far from the city, “preferably those in the mountains , ‘because they contain less glass and the ants are less fierce, so stings can be avoided”. The stones that Luz María has have been with her for 10 years and every end of October she takes them out, washes them and puts them to dry on her comal and makes her sweet gorditas with fresh corn “which are cooked over a charcoal brazier (un brasero con carbón), the old fashioned way”.

Edgar Cruz Delgado from Asomarte (1) notes that according to journalist Agustín Escobar Ledesma, the word memanxá comes from the hñahñú (2) meaning “tender corn,” so it is likely that the dish originated in the indigenous communities of the semi-desert and spread to nearby regions such as the Sierra Gorda and the Mezquital Valley in Hidalgo.

- Astomarte is website dedicated to “Tourism, destinations, getaways, gastronomy, where to sleep and where to eat in Querétaro. Events, plastic arts, cinema, dance, literature, music, children.” You can find them on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/asomarte/

- Hñähñu, better known as Otomi, it’s a language widely spoken all over central México, in the states of Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Mexico, Mexico city, Michoacan, Queretaro, and many other regions by around 400,000 speakers. The word Hñähñu is a compound word of Hñäki (Speak – it can also mean language/tongue or quarrel) and Xiñu (Nose), so the meaning it’s commonly translated as “nasal speech”

Edgar also notes that memanxás are made from chickpeas while the mamanxás are made from corn, there is little difference in the texture of the finished product but there will be a small difference that is noticeable in the flavour of the gordita. The two can easily be confused however and the names can be used interchangeably.

He also provides recipes for each.

Mamanxás

- 250 gr of raw (dried/unroasted) chickpeas

- 50 gr of butter

- 75 ml of milk

- 2 eggs

- ½ tbsp ground cinnamon

- 50 gr of sugar

- ½ tbsp baking powder

- Roast the chickpeas and grind them finely

- Add the rest of the ingredients and knead

Memanxás

- 5 maíces tiernos (young corn) or elotes (fresh corncobs)

- 100 gr of brown sugar (piloncillo)

- ½ tsp ground cinnamon

- ½ tsp baking soda

- Remove the shells from the corn cobs. Grind the kernels with the piloncillo

- Add the rest of the ingredients and knead

Both recipes then follow the same cooking process.

- Take a little of the dough and form small gorditas

- Heat your anthill stones on a comaland when they are red hot, place the gorditas on them and let them cook. You can also wrap the gorditas in banana or corn leaves and cook them directly on the griddle.

The stones being used in these images remind me of what we would call blue metal in Australia

Just remember to remove it all from your gorditas as they are definitely tooth breakers.

The Aboriginal people of Australia similarly cook a type of bread called “damper” which is cooked by placing it directly onto the hot sand under their campfires (after scraping away the coals).

References

- Title image : https://losgastronautas.com/tlaxcales/

- ¿Conocen las Toqueres o Tlaxcales? : https://guerrerolife.com/conocen-las-toqueres-o-tlaxcales/

- ¡Deliciosos! Así son los tlaxcales, panes originarios de Tlaxcala – Mexico Travel Channel : https://mexicotravelchannel.com.mx/estados/20210205/tlaxcales-panes-originarios-tlaxcala/

- Genetically engineered corn – https://www.centerforfoodsafety.org/issues/311/ge-foods/about-ge-foods#:~:text=Help%20us%20grow%20the%20food%20movement%20and%20reclaim%20our%20food.,-Contact%20Information&text=Currently%2C%20up%20to%2092%25%20of,often%20used%20in%20food%20products).

- GORDITAS DE LA VILLA ¡EXQUISITAS! : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S9KGTghcL-4

- Gorditas de maíz en piedras de hormiguero – https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=723522261961094

- La historia detrás de los tlaxcales, un icónico manjar de origen prehispánico : https://notitlax.com/nacional/tlaxcales-tlaxcala-historia-origen-receta-facil/

- Maseca GMO – https://organicconsumers.org/maseca-glyphosate-testing-results/#:~:text=In%20the%20case%20of%20the,low%20or%20no%20detectable%20values.

- Memanxás – Larousse Cocina: https://laroussecocina.mx/palabra/memanxas/

- Memanxás – https://www.asomarte.com/blog/entrada/161/memanxas-y-mamanxas/

- Piedras de Hormiguero – https://criteriohidalgo.com/noticias/hidalgo/las-gorditas-dulces-que-se-cuecen-sobre-piedras-de-hormiguero

- Pinole (Image) : https://www.maricruzavalos.com/pinole-recipe/

- Receta de tlaxcales de guayaba: Un postre delicioso : https://www.cocinadelirante.com/receta/postre/receta-de-tlaxcales-para-el-antojo-cocina-delirante

- Receta Toqueres Guerrerenses : por Sabores De México : https://lossaboresdemexico.com/receta-toqueres-guerrerenses/

- Ricas Memenshas ¿Como las conoces tú? : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UB7nwK_IQy0

- Tacachotas – https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=D6yAUnY3e60

- Tlaxcales : https://www.recetasnestle.com.mx/recetas/tlaxcales

- Tlaxcales : https://recetasdeladona.com/tlaxcales/

- Tlaxcales : https://www.mexicodesconocido.com.mx/tlaxcales.html

- Tlaxcales, un rico postre que tienes que probar : https://www.trespm.mx/estilo-de-vida/el-buen-comer/tlaxcales-un-rico-postre-que-tienes-que-probar#google_vignette