Lengua de vaca

Now, when I speak of lengua de vaca (cows tongue) I am not speaking of the actual tongue of a cow but of a wild herb or “quelite”. The herb is no doubt (as you will see further down) named for its general appearance (shape and size wise in some cases) of a cows tongue.

Commonly used and appreciated in México, the (actual) cows tongue is generally thought of as an offcut or lesser cut of meat in Australia. It is generally a meat relegated to pet food but it is a tasty meat and deserves more recognition. It can be fiddly as it is a tough cut and preparing it is usually a multistep process that involves cooking (braising/simmering and sometimes brining) and peeling before it can be eaten. Rossana at Villa Cocina (see references for the link) runs through the process quite nicely.

To cook the tongue

- 2 1/2 lbs beef tongue

- 1/2 white onion, large

- 1 head, garlic

- 1/2 tsp black peppercorns, whole

- 4 bay leaves

- 5 hierba buena/mint sprigs (Optional)

- 4 (small) guajillo chiles (or use chipotles en adobo)

- 1 1/2 tsp salt

- 1/2 tsp dry (Mexican) oregano

- 8 cups of water

Directions

- Rinse and wash tongue in cold water

- To reduce the cooking time, cut the tongue in about 6 medium size pieces.

- Transfer the tongue, onion, dry guajillo chiles (which have been rinsed – or wiped with a damp cloth – to remove any dust and had their seeds and veins removed) into a large pot. Cut the head of garlic in half and add it in along with the bay leaves, peppercorns, dry oregano, salt, hierba buena and up to 2 inches of water above the tongue, about 8 cups.

- Bring to a boil over medium high heat, then lower to medium low for a gentle simmer. Cover and let it cook for about 1 1/2 to 2 hours or until fork tender.

- When the tongue is fork tender remove from the broth and peel off the skin while still hot. Unless you have the fireproof, tortilla flipping fingers of an abuela you might need to wear gloves for this step (and if you cleaned your chiles with your bare hands in the earlier step then I would recommend washing your hands well before going to the toilet – particularly if you are a man – or before you touch your face or rub your eyes. You might be in for quite a sorpresa caliente otherwise)

- It is now ready to be prepared for your tacos.

Cleaning your chiles

The seeds and veins (sometimes called the placenta) are removed in this dish before they are added to the pot. This usually diminishes the heat of the dish somewhat and is not always a necessary step (unless you don’t want the seeds in your dish). If you are rehydrating the chiles in boiled water you can always leave the chiles whole and then strain them through a sieve (after they have been blended into a paste) to remove the seeds and other gritty bits.

The seeds can also be saved and used an ingredient in various dishes (more on this further down when we look at mixmole). They operate somewhere between being a spice and an ingredient similar to that of pumpkin seeds.

Back to the herbs

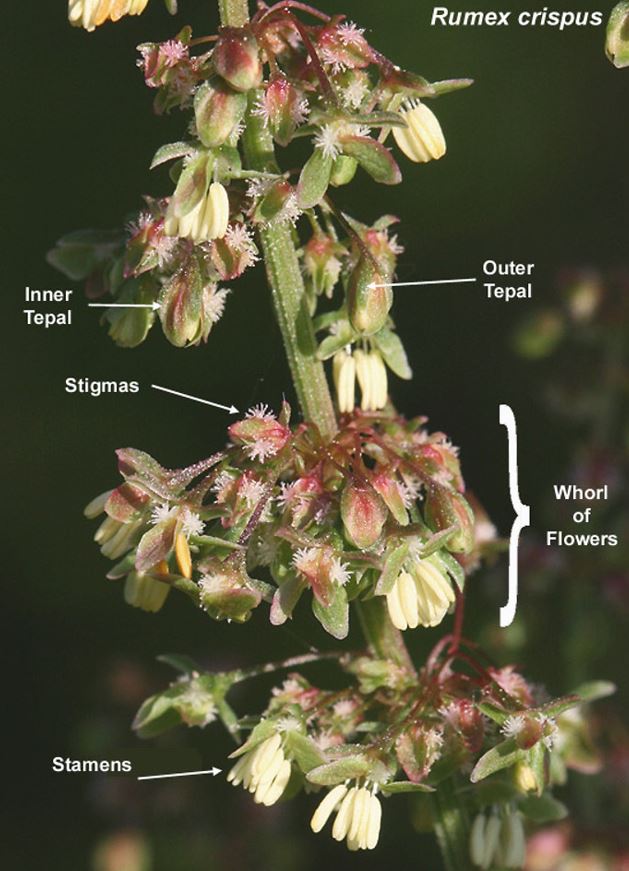

Lengua de vaca is a name that designates several species of herbs in the genus Rumex (of the Polygonaceae family). Alongside the local species R.mexicanus, the varieties most commonly consumed in Mexico are R.acetosa, R.crispus and R.hymenosepalus.

Rumex crispus – Yellow Dock – was mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his “Herba Britannica” (circa AD 23). Dioscorides,, the Greek physician and pharmacologist who authored the famous “De Materia Medica”, recommended the various Docks as pot herbs that would help clear afflicted skin and allay itching.

Etymologically its name is said to de derived from….. Rumex = lance/javelin/dart referring to the shape of the leaves and crispus meaning curled (referring to the wavy margins of the leaf – which also gives it the alternate name of “curled dock”. Minevra – further down – notes this as being a “chino” or Chinese edge to the leaf). I have also seen Rumex translated as “acidic” and “to suck” (Roman soldiers used to chew on wads of the herb to promote salivation so as to relieve thirst)

This quelite is used as a condiment due to its sour and slightly bitter taste. It is related to dock and sorrel, both of which are commonly foraged (and grown) plants the world over. In México its use varies with location as Mexican cuisine varies enormously by region.

In Culhuacán and Xochimilco, in the Federal District (El D.F – the CDMX), leaves are added to duck stews with guajillo chile, epazote, cilantro and garlic; they are also prepared in mixmole with charales (1) and pumpkin seeds; they are used to accompany various tacos; it is customary to mix them with mulato, guajillo and pasilla chiles to make a spicy sauce.

- charales are a type of small fish that you could substitute with whitebait in Australia and new Zealand

In Guerrero, lengua de vaca is used in various stews, especially in the green pozole of Chilapa and in mole like tlatonile.

In Tlaxcala (where this quelite is called amamaxtlas) they are added (along with frijoles amarillo) to a dish called tlatlapas

In Naupan, in the northern mountains of Puebla, the leaves are cooked with lard, onion and salt, and eaten hot in tacos.

In Tuxtla, a dish is prepared with papas fritas and lengua de vaca which are then cooked in a sauce of tomato, onion, garlic, chipotle peppers and salt; the stew is eaten hot, accompanied by tortillas. Lengua de vaca is also prepared with pork, with a sauce of tomato, chipotle peppers, onion, garlic, cinnamon sticks, cloves and salt in which the pork is cooked and at the end the herb is added. It is eaten hot, with sauce and corn tortillas.

In Acatlán, Veracruz, lengua de vaca chileatole is prepared.

In the region of Los Tuxtlas it is accompanied with (papas en chipotle) chipotle potatoes.

Lengua de vaca, or cow’s tongue

Rumex mexicanus Meisn. [syn. R. salicifolius var. mexicanus (Meisn.) C.L.Hitchc.]

ENGLISH: dock, Mexican dock, Mexican willow, white dock

SPANISH: acelga cimarrona hierba agria, lenguas, lengua de toro, lengua de vaca, vinagrera

USES/NOTES: Leaves and seeds are eaten as vegetables.

R.mexicanus – mamaxtla (Rumex mexicanus) The root of the mamaxtla (Rumex mexicanus) and the flower tlacoizquixochitl (Cordia alba) are mentioned for diuresis. The patient drank with water a mixture of flowers, mamaxtla root, red earth, eztetl (blood flower), and white earth. With this mixture diuresis was reestablished. (Peña 1999) – also “amamaxtla” (Hernandez 1942)

According to various authors (Diaz 1976; Estrada Lugo 1989; Ortiz de Montellano 1990; Miranda & Valdez 1964; Pico & Nuez 2000; Tucker & Janick; Valdés Gutiérrez etal 1992) the Rumex species was known prehispanically. Various Náhuatl names for the species are as follows

Rumex mexicanus : amamaxtla : amamaxtla purgante (1); amaxtlatl; axixpatli coztic axix = urine : pahtli – denotes medicinal herb : coztic = something yellow/red/gold) ; axoxoco : axocopac : axocopaconi (sour aquatic edible herb); mā-māxtla (loincloths)

- ruibarbo llamado de los frailes

Amamaxtla purgante : ruibarbo llamado de los frailes (Friars rhubarb)

In the Historia Natural de la Nueva España 1 // Libro Tercero // Capitulo CLXXX. Del Amamaxtla purgante… (Natural History of New Spain 1 // Third Book // Chapter CLXXX (180). Of the purgative Amamaxtla)…It is noted that…..

The root of this plant so reproduces and imitates the root of the true rhubarb in flavour, colour, odour, substance, and properties, that if it were not distinguished from it by its leaves, which end in a point (whereas the former are narrow at the base and broader at the tip), any one who examined both plants would say that it was the same Alexandrian rhubarb; for all which reason we believe that this garden rhubarb is a kindred of the true rhubarb, and can substitute for it in its absence, and perform almost the same functions;

- it certainly purges bile gently and with a certain tonicity,

- it has some subtle parts, which are purgative, and others which are coarse and astringent,

- the Indians are accustomed to use the juice, expressed in doses of one and a half drachms, as a purge, and the remainder, in the same dose, as a medicine for constipation of the stomach; taken in its entirety in the amount of two drachms, it is sufficient to purge the bile of those whose stomach is not very hard,

The same plant? A Rumex? Hard to tell. There are similarities, but the flower is off. Rumex species tend to have a flower spike rather than individual blossoms.

Rumex patientia : Xococotl

Rumex pulcher : atlinam; atlinan

Commonly utilised species of Rumex

SORREL (Rumex acetosa L.)

acetosum comes from the Latin acetum meaning vinegar.

Aggregated with R. crispus L. by MAD. “Frankly, I think most species seem to share the same chemistries and indications”. (Duke 2002)

Activities (Sorrel) — allergenic; antibacterial; antipyretic; antiscorbutic; antiseptic; ascaricide (1); depurative; diaphoretic; diuretic; haemostat; hypoglycaemic; laxative; litholytic (2); secretagogue (3); stomachic (4); vermifuge

- used to treat ascariasis that is caused by infections with parasitic nematodes (roundworms) of the genus Ascaris

- used for the dissolution of stones, especially calculi such as gallstones and kidney stones

- a substance stimulating secretion (as by the stomach or pancreas). It often refers to hormones (i.e. insulin) and likely is responsible for the hypoglycaemic (blood glucose lowering) action of this herb

- Stomachic is a old term for a medicine that serves to tone the stomach, improving its function and increases appetite. Modern pharmacology does not have an equivalent term for this type of action

The whole herb is employed medicinally, in the fresh state. The action is diuretic, refrigerant and diaphoretic, and the juice extracted from the fresh plant is of use in urinary and kidney diseases

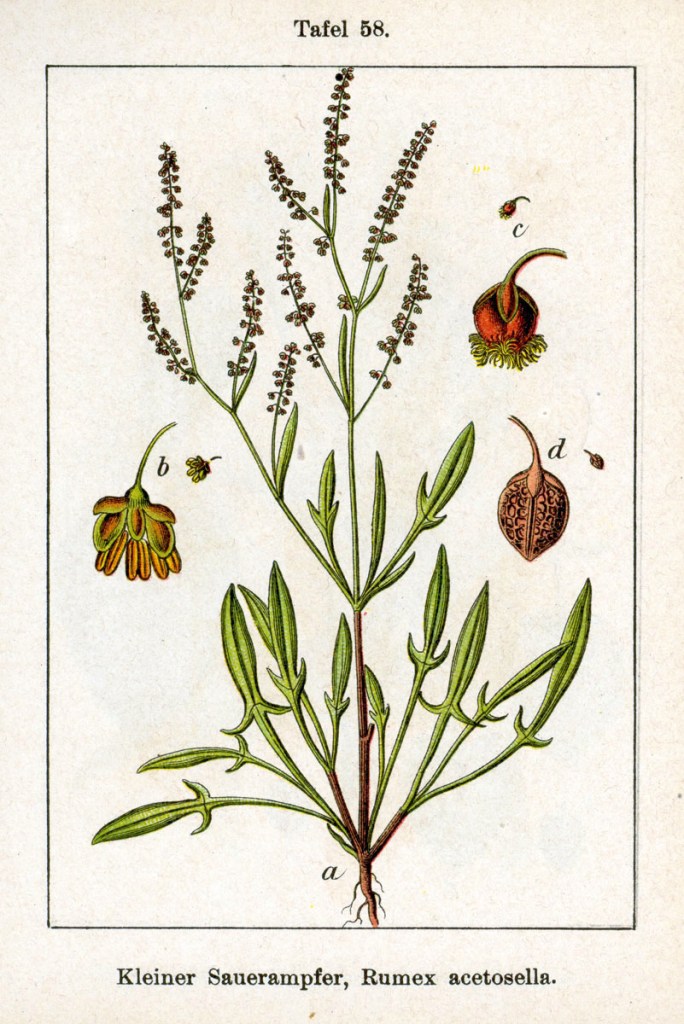

SHEEP SORREL (Rumex acetosella L.)

Used interchangeably with R. acetosa.

Also called : acedera, acedera menor, acederilla, acedorilla, acetosa, lengua de pájaro, moradilla, romaza, vinagrera, vinagrerita, vinagrillo, vinagrita, xocoyolpapatla, quelite agrio, lengua de vaca chiquito, Lengua de Pájaro

USES/NOTES: Acidic leaves (see Cautions and Contraindications in Yellow Dock re oxalic acid)

Medicinal activities (Sheep Sorrel) — allergenic; antipyretic; antitumor; depurative (1); diaphoretic (2); diuretic; haemostat (3); laxative; peristaltic (4)

- formerly known as alteratives or blood purifiers, depurative herbs are largely used to treat chronic skin and musculoskeletal disorders.

- an action that produces or promotes sweating by increasing circulation in the periphery of the body. This has the value of helping to skin eliminate waste from the body and is often used to help relieve or break fevers.

- acts by stopping bleeding from small blood vessels by stabilizing the wall of these blood vessels and improving platelet (blood cells that help in clotting)function

- encourages a series of wave-like muscle contractions that move food through the digestive tract. This action also assists the laxative effects of these plants

YELLOW DOCK (Rumex crispus L.)

This is the main variety of this family that is used medicinally

Synonym(s) Curled Dock, Rumex odontocarpus I. Sandór

Also called : acelga, aselgas, bardana, cimakatwakas, cuchi-ula, gulag, epazote, hierba agria, hojas de mala hierba, hualtata, ixcaua (Otomí), k’ita aselgas, lengua de toro, lengua de vaca, llakhi, llaqhi, mostaza, pasi ma’kat, pira de berraco, pira de puerco, romazo, scocnakak (Totonac), venenillo, vinagrera, vinagrillo, xocoquilit (Nahuatl), xokokilitl, quelite agrio

Culinary use: The young leaves can be eaten as food in spring . Simply blanch or soak in boiling water for a few minutes to remove excessive bitterness. The root can also be dried, ground and used mixed in with flour.

Medicinal uses : dry cough, sore throat, laryngitis; Help vascular disorders and internal bleeding; Remedy against internal parasites – tapeworm and roundworm; Cleansing herb – stimulate liver and gall bladder.; Trigger excretion of toxins; Stimulant laxative effect – constipation; Depurative – to help long term conditions like arthritis, jaundice, chronic skin diseases like acne and eczema and fungal infections; Blood tonic – anaemia

Medicinal actions : allergenic, alterative (1), analgesic, anthelmintic (2), antiangiogenic, antibacterial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antipyretic, antirheumatic, antiscorbutic, antiseptic, antispasmodic,astringent (3), bitter (4), cholagogue (5), choleretic (5), cytotoxic, depurative (6), discutient (7), emetic, fungicide, hepatic (8), hepatoprotective, hypotensive, laxative, parasiticied, peristaltic, tonic (blood)

- Alteratives are herbs that ‘alter’ the condition in a tissue by eliminating metabolic waste via the liver, large intestine, lungs, lymphatic system, skin and kidneys.

- Anthelmintics or antihelminthics are a group of antiparasitic herbs that expel parasitic worms (helminths) and other internal parasites from the body by either stunning or killing them and without causing significant damage to the host

- Astringents contain tannins that act to precipitate proteins and draw tissues together, tightening and toning them to reduce secretions and discharge. Astringents also tend to stop bleeding and can act on tissues with which there is no direct contact.

- Bitters stimulate digestion by enhancing digestive secretion and peristaltic movements of the gut. They act via a reflex from the taste buds to the brain then through the vagus nerve to whole digestive system. Often these herbs are combined with warming digestives to balance the cold nature of bitters.

- Cholagogues promote the production of bile in the liver. A choleretic is a type of cholagogue that promotes the release of bile from the gall bladder into the duodenum. Cholagogues have an alterative and laxative effect. Cholagogues are contra-indicated if there is acute liver failure, obstructive jaundice, painful gallstones or cholecystitis

- Depurative is a substance that improves detoxification and aids elimination to reduce the accumulation of metabolic waste products within the body. They were formerly known as alteratives or blood purifiers and are largely used to treat chronic skin and muscoskeletal disorders.

- Discutients – capable of dissipating diseased matter.

- Hepatics are herbs that generally support liver function by decongesting as well as supporting bile flow.

Constituents

Yellow dock root contains: 2-4% anthraquinones including chrysophanol, emodin, rhein, nepodin and physcion (aglycones). Tannins such as Catechol (5%) (condensed-type). Other plant constituents documented include oxalic acid, oxalates, chrysophanic acid, rutin, flavone glycosides; vitamin C; many different carotenoids including beta-carotene, chlorophyll, organic acids (i.e., malic, oxalic, tannic, tartaric and citric) and phytoestrogens. Minerals include calcium; phosphorus; magnesium; potassium, and silicon, along with iron, sulphur, copper, iodine, manganese, and zincand a complex volatile oil.

Yellow dock (R.crispus) recieves its name from reddish orange compounds (anthraquinone glycosides) in the root of the plant. These compounds are also responsible for much of its medicinal actions. Once the anthraquinone glycosides reach the colon the gut bacteria break them down and the anthraquinones act directly on the gut lining to stimulate peristalsis in the bowel. These constituents also create the laxative effects of the herb. Anthraquinones also possess antibacterial, antiparasitic, insecticidal, fungicidal, and antiviral properties, deterring the growth of pathogens in the gastrointestinal system. Emodin (one of the main anthraquinones) has significant anti-microbial activity, specifically against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Tannins in the plant have a toning and strengthening effect on the bowel wall which balances and moderates some of the stimulating effect of the anthraquinones on the bowel, giving yellow dock a laxative action which is relatively gentle.

The glycosides in the plant are known for their hepatoprotective effects. They can help to stimulate the liver, which in turn helps heal poor absorption of nutrients and increases bile production. Regular consumption of this herb will stimulate the detoxification process in liver and boost the production of bile. This assists the liver in eliminating toxins, excess hormones and other waste products.

Energetically, yellow dock is cooling and cleansing, binding and drying. It is a cooling remedy for excessive heat in the gastrointestinal tract.The action of cleansing the liver and bowel reduces internal heat, clearing liver stagnation and promoting the flow of bile.

Yellow dock is also a nutritive and tonic herb as it accumulates and concentrates minerals from the soil it grows in, giving a nutrient profile which is high in calcium, magnesium, zinc, copper, manganese, and vitamins A, C and E. Yellow dock roots in particular are quite effective at extracting iron from the soil and converting it into a bio-available form, making the plant iron-enriched which explains its traditional use for treating anaemia (1). Yellow Dock is one of the best sources of plant based (non-heme) iron. The iron content of both leaf and root is around 30mg per 100g. Yellow Dock leaves are extremely high in vitamin C and has been traditionally used to treat scurvy because of this.

- Anemia is a problem of not having enough healthy red blood cells or hemoglobin to carry oxygen to the body’s tissues. Hemoglobin is a protein found in red cells that carries oxygen from the lungs to all other organs in the body. Having anemia can cause tiredness, weakness and shortness of breath.

Interactions

If used excessively, yellow dock may increase potassium loss, creating a potential interaction with diuretic thiazides. There is the potential for an interaction with concurrent ingestion of stimulant laxatives medicines.

Cautions and Contraindications

If using this plant as a foodstuff one thing that will be noted is that many of them are sour tasting. This is due to the presence of oxalic acid. The leaves should not be eaten in large amounts since the oxalic acid can lock-up other nutrients in the food, especially calcium, thus causing mineral deficiencies. The oxalic acid content will be reduced if the plant is cooked (and the cooking/blanching water disposed of). Oxalate and calcium bind together in the intestine and leave the body together in the faeces (hence the potential problem with mineral deficiencies). If there is not enough calcium, then the extra oxalate will have nothing in the intestine to bind to, so it will be absorbed into the bloodstream and end up in the urine, where it can form calcium oxalate stones. If you are prone to kidney stones then care must be taken if eating this plant as excess consumption may increase the formation of kidney stones.

Yellow dock should be avoided or only taken under the guidance of a medical herbalist if there is any intestinal obstruction or inflammatory bowel diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.

Avoid in pregnancy due to a reflex action on the uterus, and when breast-feeding as small amounts can be excreted in breast milk.

Preparation

- Infusion/Decoction (root): Simmer for 20 minutes.

- Compress (leaf): Make a decoction of the plant material and allow to cool slightly. Use a clean pad of lint or another absorbent material to apply the liquid to the affected area of skin. Replace regularly with a clean pad.

- Poultice: Fresh leaf can be finely chopped to make a poultice which is applied directly to the skin, and held in place with a cloth or bandage.

Dosage

- Decoction (root): 5–10g dried root per day

- Tincture (root): 1–4ml, three times per day, 1:5, 45-60% (2, 27). Up to 30ml/week of a 1:2 extract. Take 1–2ml daily for 6 weeks to build up iron levels.

- Fluid Extract (1:1 extract): 2–4ml, three times per day

- Powder or Capsules: 100mg, 3 times a day. 0.8–2g per day.

Use: (in Peruvian Highlands)

- Uterine Infection, Kidney Inflammation / Whole plant, fresh / Oral / Boil 20g of Acelga in 1 litre of water for 10 mins. Drink 3 times a day for 1-1/2 months.

- Inflammation (Internal Female Organs), Vaginal Inflammation / Whole plant, fresh / Topical / Boil whole plant in 1/2 litre of water for 10 mins. Do not mix with other plants. Elevate legs in a “V” position. Pour wash into Vagina and allow to sit for 10 mins. Go to the restroom and contract vaginal muscles to expel wash. Repeat process once more immediately. (Bussman & Sharon 2015)

Rumex hymenosepalus

The species name, “hymenosepalus”, means “membranous sepals” and refers to the 3 inner segments that become papery when the plant is in fruit

Also called : cañagria, canaigre, canegra, ganagre, hierba colorada, raíz del indio, ruibarbo silvestre

Medicinal activities (Canaigre) — anthelminthic; antibacterial; anti-HIV; anti-inflammatory; antimutagenic; antioxidant; antispasmodic; antitumor; antiviral

Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database goes into much greater detail on the biological activities generated by the various phytochemicals found within R.hymenosepalus (and I won’t go into them here but I’ll list them for you). Many of these actions are relvant to in-vivo (within the human body) functions but many of them will also have been found in in-vitro (usually referred to as “test-tube” experiments) and in animal testing (which may or may not transfer into the same actions within a human body). As you can see from the list below this is an extremely medicinally active plant.

Absorbent, Anthelmintic, Antibacterial, Anticancer, Anticariogenic, Antidiarrheic, Antidote (Iodine), Antidysenteric, Antihepatotoxic, AntiHIV, Antihypertensive, Antiinflammatory, Antilipolytic, Antimutagenic, Antineoplastic, Antinephritic, Antinesidioblastosic, Antiophidic, Antioxidant, Antiradicular, Antirenitic, Antispasmodic, Antitumor, Antitumor-Promoter, Antiulcer, Antiviral, Calcium-Antagonist, Cancer-Preventive, Capillariprotective, Carcinogenic, Chelator, Cyclooxygenase-Inhibitor, Emollient, Fungicide, Glucosyl-Transferase-Inhibitor, Hepatoprotective, Immunosuppressant, Keratitigenic, Lipoxygenase-Inhibitor, MAO-Inhibitor, Occuloirritant, Ornithine-Decarboxylase-Inhibitor, Pesticide, Poultice, Psychotropic, Xanthine-Oxidase-Inhibitor

Culinary use of Lengua de vaca

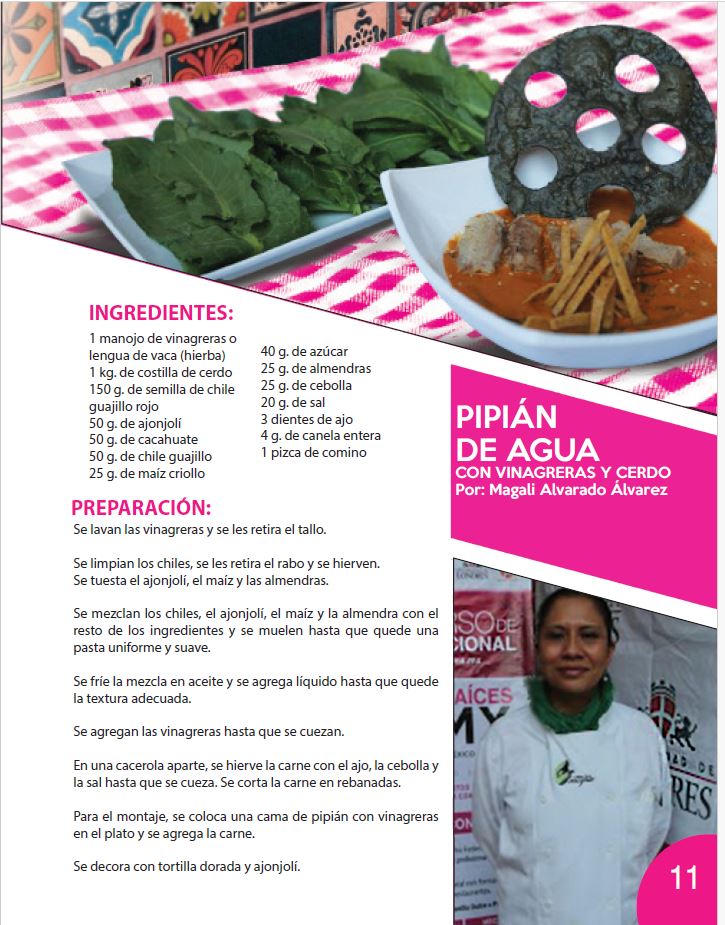

Secretaria de Pueblos y Barrios Originarios y Comunidades Indígenas Residentes (previously SEDEREC – Secretaría de Desarrollo Rural y Equidad para las Comunidades) supplies some very interesting (and free) cookbooks showcasing the rural and indigenous cooking from many regions in Mexico (see References for a link to some). Below are a few recipes from one such book (that focusses on the CDMX) that include lengua de vaca.

Flavours and Roots of México City. You can also find them on Facebook.

First we’ll start with some recipes from the chinamperos of Xochimilco

Chinampas are a remnant of Aztec era agriculture, when Mexico City (then called Tenochtitlan) was a city on/in a lake.

Tlemolli (or tlemole/clemole) is a type of Mole de Olla (pot mole) which is in essence a type of guisado (stew) flavoured with tomatoes and chiles.

Pipián is a (more or less) type of mole made with puréed greens and thickened with ground pumpkin seeds. The dish has been said to have origins in the ancient Aztec, Purepecha and Mayan cuisines.

Another dish of Xochimilco and other regions of the lake dwelling peoples of Anahuac is that of an unusual masa free type of “tamal” called a tlapique. Vitamina T : The Tlapique. Cousin of the Tamal.

The lake dwellers of Tláhuac, a Colonia (neighbourhood) in an area close to México City and (which was once an island in a lake) covering an area where the former lakebeds of Lake Chalco and Lake Xochimilco met provide here a recipe for mixmole (or michimolli).

“Mixmole or Michimolli”

A guisado (stew) of fish in a salsa verde : Etymology: Michimolli . From michin (fish) and molli (sauce/mole)

Ingredients:

(4 servings)

- 1 kg of fish (carp, catfish or white fish)

- 1 bunch of lengua de vaca (this recipe mentions it as being Rumex obtusifolius)

- 100 grs. of dried chile seeds

- 2 cloves of garlic

- 2 Onions

- 4 sprigs of cilantro

- 1 branch of epazote

- 1 large tablespoon of lard

- Salt to taste

Preparation :

- Grind the raw (untoasted) chile seed with one of the onions and the garlic in your molcajete 9or a mortar and pestle – this will work much better than a blender. You want a nice paste).

- Slice the other onion and sauté it in the lard. Add the ground chile seed mix, and a little broth (to make a thickish sauce – much like atole this can be as runny or as thick as you desire)

- The lengua de vaca is washed and the veins (the set of central nerves of the leaf) are removed. They are added to the pot with the fried chile seed/onion mix. Add the epazote and cilantro.

- When the ingredients are cooked, add the fish and let it simmer for another 15 minutes. Add more broth if necessary

Mixmole can range in texture from a thinnish soup like liquid to a thick mole like puree.

I do go into greater detail into this dish and its various incarnations in a previous Post : Michimole : Mole Salvaje (Wild Mole)

In Atlacomulco, particularly San José del Tunal, one writer (Minerva) notes (via a blog post in El Cuexcomate) they have a special food or dish eaten during la época de sequía (the dry season called lengua de vaca (Rumex sp.) in chilaca or guajillo chili. This is an interesting change as quelites are typically a plant of la temporada de lluvias (wet season) (1). Many quelites are tender plants available only during the wet season (or in paricularly fertile regions such as the vallies of Oaxaca). Not only in Atlacomulco do these (Rumex) herbs grow in a drier environment but Minerva asserts that this plant is not only more palatable but also more nutritious during the dry season. “The leaves are collected only during the dry season because the flavour of the food is pleasant and as they would say locally “no sabe a hierba” (it does not taste like grass), this is influenced by the water content in the plant. During the rainy season, plants absorb a greater amount of water, causing nutrients – such as proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, among others – to be present in lesser quantities.”

She also maintains that “ the collected leaves should have a wavy or “chino” (Chinese) edge and be completely green, because leaves with smooth, red edges cause a bitter taste”. This has also been noted by others who state that reddish patches on the leaves give them a bitter taste (which is not surprising if it is the anthraquinones causing the colouration). It does likely mean that the leaves will be more “medicinal” in this state though.

It is recommended that this be a dish best eaten after a hard days work in the fields.

Ingredients (for 8 people)

- 1 grocery bag full of Rumex sp. leaves

- ½ kg of chilaca or guajillo chili

- 100-200 g of sesame seeds

- ¼ of white onion (chopped)

- Salt

- Oil

- Water

Preparation

- Wash the collected leaves to remove any soil or traces of grass leaves..

- Blanch the cleaned leaves for 1 minute or less in boiling water, remove from heat and strain (carefully)

- Rehydrate the chiles in boiled water

- On the comal (or in a dry pan), toast the sesame seeds, stirring constantly; once they have a light brown colour, remove them from the heat

- Grind the rehydrated chiles with the toasted sesame seeds in a molcajete (or blender).

- Sauté the onion in a bowl with oil; then, pour in the ground chile. Some people strain the chile as they drain it and add hot water to prevent the broth from thickening too much.

- Add the boiled leaves and salt to taste, and let it cook for 30 minutes.

- Serve

Minerva recommends serving the dish with warm (hecho a mano, por supuesto.) tortillas and dulce de xoconostle (candied xoconostle) (1) and your favourite drink.

- The xoconostle is a fruit of a species of Opuntia cactus. Frutos de Cactus : Xoconostle

Tlatlapas

Soledad and Juanita Sanchez Alarcon from the region of San Dionisio Yauhquemecan, Tlaxcala give a recipe for Tlatlapas de frijol amarillo on the Re-Comiendo Mexico blog. Traditionally this recipe would also use tequesquite in the cooking water to help soften the frijoles.

Ingredients

- 160 gr frijoles amarillo

- 2 lt of water

- 2 branches of epazote

- 2 nopales

- 2 chiles chipotle meco

- 4 branches of amamaxtlas

Method

1. Toast the beans on the comal (or in a dry pan) over low heat

2. Grind the beans finely into powder

3. Cut the (trimmed and despined) nopales into strips and roughly chop the amamaxtlas

4. Dissolve the bean powder in warm water and then add it to the rest of the boiling water. Keep on the heat until the mixture has thickened and the bean has cooked.

5. Add the epazote and amamaxtlas and let it simmer for 10 more minutes

There are two primary types of chipotle chiles —Chipotle Morita and Chipotle Meco. Chipotle Meco, also known as chili ahumado are the preferred chipotle chile in Mexico. Meco, which means “brown coloured” in Mexico, are chiles that are allowed to stay on the vine even longer than their Morita counterparts and then smoked for twice as long. They turn ashy brown from the smoke and heat; whole Chipotle Meco look almost cigar-like in their appearance. Ripening and smoking the peppers for an extended time means Chipotle Meco are a bit bigger than Chipotle Morita and gives them a more rich and smoky flavour.

Get into wildcrafting.

Discover quelites.

Eat your weeds people.

References

- Barnes, Joanne; Anderson, Linda A and Phillipson, J David (2007) Herbal Medicines, Third edition : Pharmaceutical Press : Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain : ISBN 978 0 85369 623 0

- Basurto, Francisco & Martínez-Alfaro, Miguel & Villalobos-Contreras, Genoveva. (2017). Los Quelites de la Sierra Norte de Puebla, México: Inventario y formas de preparación. Botanical Sciences. 49. 10.17129/botsci.1550.

- Bone K and Mills S. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013.

- Brinker, FJ. Herbal Contraindications & Drug Interactions: Plus Herbal Adjuncts with Medicines. Eclectic Medical Publications, 2010.

- Bussmann, Rainer W. & Sharon, Douglas (2015) Medicinal plants of the Andes and the Amazon The magic and medicinal flora of Northern Peru : ISBN-10:0-9960231-2-7

- Delia Castro Lara, Francisco Basurto Peña, Luz María Mera Ovando, Robert Arthur Bye Boettler (2011) Los quelites, tradición milenaria en México : Primera edición en español: agosto 2011 : ISBN: 978-607-12-0202-4

- Díaz, J.L. 1976. Índice y sinonimia de las plantas medicinales de México. México: Instituto Mexicano para el Estudio de las Plantas

- Duke, James A., (2002) Handbook of medicinal herbs 2nd ed. Previously published: CRC handbook of medicinal herbs. ISBN 0-8493-1284-1

- Estrada Lugo, E. 1989. El Códice Florentino: Su información etnobotánica. México: olegio de Postgraduados, Institución de Enseñanza e Investigación en Ciencias Agricolas, Montecillo.

- Ford, Karen Cowan (1975) LAS YERBAS DE LA GENTE: A STUDY OF HISPANO-AMERICAN MEDICINAL PLANTS : MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 60 : ISBN (print): 978-0-932206-58-9

- Hernandez, Francisco (1942) HISTORIA DE LAS PLANTAS DE NUEVA ESPAÑA : TOMO I (Libros l y 2) : IMPRENTA UNIVERSITARIA MEXICO, 1942

- Hoffmann D. Medicinal Herbalism, The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press; 2003.

- Humeera, N.; Kamili, A.N.; Bandh, S.A.; Lone, B.A.; Gousia, N. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of alcoholic extracts of Rumex dentatus L. Microb. Pathog. 2013, 57, 17–20.

- Idris OA, Wintola OA, Afolayan AJ. Comparison of the proximate composition, vitamins (ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol and retinol), anti-nutrients (phytate and oxalate) and the GC-MS analysis of the essential oil of the root and leaf of Rumex crispus L. Plants. 2019; 28;8(3): 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8030051

- Jeelani SM, Farooq U, Gupta AP, Lattoo SK. Phytochemical evaluation of major bioactive compounds in different cytotypes of five species of Rumex L. Industrial Crops and Products. 2017;109:897-904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.09.015

- Korpelainen, Helena & Pietiläinen, Maria. (2020). Sorrel (Rumex acetosa L.): Not Only a Weed but a Promising Vegetable and Medicinal Plant. The Botanical Review. 86. 10.1007/s12229-020-09225-z.

- Li, Jing-Juan & Li, Yong-Xiang & Li, Na & Zhu, Hong-Tao & Zhang, Ying-Jun. (2022). The genus Rumex (Polygonaceae): an ethnobotanical, phytochemical and pharmacological review. Natural Products and Bioprospecting. 12. 10.1007/s13659-022-00346-z.

- Mateos-Maces, L.; Chávez-Servia, J.L.; Vera-Guzmán, A.M.; Aquino-Bolaños, E.N.; Alba-Jiménez, J.E.; Villagómez-González, B.B. Edible Leafy Plants from Mexico as Sources of Antioxidant Compounds, and Their Nutritional, Nutraceutical and Antimicrobial Potential: A Review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 541. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9060541

- Mhalla, D.; Bouaziz, A.; Ennouri, K.; Chawech, R.; Smaoui, S.; Jarraya, R.; Tounsi, S.; Trigui, M. Antimicrobial activity and bioguided fractionation of Rumex tingitanus extracts for meat preservation. Meat Sci. 2017, 125, 22–29

- Miranda, F., and J. Valdés. 1964. Comentarios botánicos. In Libellus de medicinalibus indorum herbis manuscrito Azteca de 1552 segun traduccion Latina de Juan Badiano version Espanola con estudios y comentarious por diversos autores, ed. M. de la Cruz, 243–284. México: Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social.

- Mostafa, H.A.M.; El-Bakry, A.A.; Eman, A.A. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of di_erent plant parts of Rumex Vesicarius L. at early and late vegetative stages of growth. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 4, 426–435.

- Orbán-Gyapai, O.; Liktor-Busa, E.; Kúsz, N.; Stefkó, D.; Urbán, E.; Hohmann, J.; Vasas, A. Antibacterial screening of Rumex species native to the Carpathian Basin and bioactivity-guided isolation of compounds from Rumex aquaticus. Fitoterapia 2017, 118, 101–106.

- Ortiz de Montellano, B. 1990. Aztec medicine, health, and nutrition. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Peña, José Carlos (1999) Pre-Columbian Medicine and the Kidney : Origins of Nephrology – Antiquity : Am J Nephrol 1999;19:148–154 : Hospital Mocel y Hospital Angeles del Pedregal, México D.F., México

- Pelzer CV, Houriet J, Crandall WJ, Todd DA, Cech NB, Jones Jr DD. More than Just a Weed: An Exploration of the Antimicrobial Activity of Rumex Crispus Using a Multivariate Data Analysis Approach. Planta medica. 2022; 88(09/10):753-61. DOI: 10.1055/a-1652-1547. https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/html/10.1055/a-1652-1547

- Pengelly A. The constituents of medicinal plants: an introduction to the chemistry and therapeutics of herbal medicine. CABI Publishing; 2004.

- Picó, B., and F. Nuez. 2000. Minor crops of Mesoamerica in early sources (I). Leafy vegetables. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 47: 527–540.

- Tucker, Arthur O. & Janick, Jules; Flora of the Voynich Codex “An Exploration of Aztec Plants” ISBN 978-3-030-19376-8; ISBN 978-3-030-19377-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19377-5

- Valdés Gutiérrez, J., H. Flores Olivera, and H. Ochoterena-Booth. 1992. La botánica en el Codice de la Cruz. In Estudios actuales sobre el libellus de medicinalibus Indorum herbis, ed. J. Kumate, M.E. Pineda, C. Viesca, J. Sanfilippo, I. de la Peña Páez, J. Valdéz Gutiérrez, H. Flores Olvares, H. Ochoterena-Booth, and Z. Lozoyal, 129–180. México: Secretaria de Salud.

- Vasas A, Orbán-Gyapai O, Hohmann J. The Genus Rumex: Review of traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Journal of ethnopharmacology. 2015;175:198-228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.09.001

Websites and Images

- A modern-day chinampa – By Emmanuel Eslava – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=43643623

- Charales – https://tierrafertil.com.mx/2017/04/26/crece-produccion-de-charal-en-mexico/

- Chileatole Veracruzano – https://www.identidadveracruz.com/2020/02/02/el-chileatole-verde-de-tacamalucan/

- Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database – https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/

- Lengua de vaca : Diccionario gastronómico : Larousse Cocina: https://laroussecocina.mx/palabra/lengua-de-vaca/

- Lengua de vaca o vinagrera – https://claustronomia.elclaustro.mx/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/LenguadeVaca_28Jul22.pdf

- Minervas lengua de vaca – http://www.cuexcomate.com/2014/02/lengua-de-vaca-rumex-sp-en-chile.html

- Mixmole in Tlahuac – https://revistanosotros.com.mx/2022/06/25/la-cocina-tradicional-lacustre-de-tlahuac-en-un-recetario/

- Peeling your cows tongue (image) – https://healthyrecipesblogs.com/beef-tongue-recipe/

- Pozole verde via Pozole Chilpancingo on Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/PozoleChilpancingo/posts/pozole-verde-estilo-guerrero-preparalo-a-tu-gusto-dejate-consentir-visitanos-en-/1533048373710336/

- Preparing your cows tongue – https://villacocina.com/beef-tongue-tacos-tacos-de-lengua-recipe/

- Quelites from the chinampas via Mundo Xochimilco on Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=4209238859158993&set=pcb.4209238912492321

- Rumex acetosa : https://plantsam.com/rumex-acetosa/

- Rumex crispus : Weeds of Australia : https://keyserver.lucidcentral.org/weeds/data/media/Html/rumex_crispus.htm

- Rumex crispus flower structure – https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/species/rumex/crispus/

- Rumex hymenosepalus : Vascular Plants of the Gila Wilderness : https://wnmu.edu/academic/nspages/gilaflora/rumex_hymenosepalus.html

- Rumex mexicanus Meisn : Conabio : http://www.conabio.gob.mx/malezasdemexico/polygonaceae/rumex-mexicanus/fichas/pagina1.htm

- Rumex salicifolius var. mexicanus : SELNet : https://swbiodiversity.org/seinet/taxa/index.php?taxon=15931&clid=2953

- SEDEREC Cookbooks – https://www.sepi.cdmx.gob.mx/recetarios-sederec

- Tacos de lengua in the CDMX – https://www.chilango.com/comida-y-tragos/tacos-gigantes-de-lengua/

- THE MANY QUELITES DE MÉXICO : https://theeyehuatulco.com/2021/07/28/the-many-quelites-de-mexico/

- (Thin) Michmole with crab – De BurseraLinanoe – Trabajo propio, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=91528252

- Tlatlapas de frijol amarillo – https://recomiendomexico.wordpress.com/2018/02/25/tlaxcal-tlatlapas-de-frijol-amarillo/

- Tlatonile de milpa – https://www.mexicanacomeplantas.com/muy-mexicanas-recetas/tlatonile-de-la-milpa