Purchased online (through eBay) as a gift for my birthday in 2024

The seller advertised the piece as being An extremely beautiful work of ancient mesoamerican religious art, carved in a very nice deep green “Chalchihuitl” (1) Jade Stone and notes that this item……DEPICTS A VERY CLASSIC TEOTIHUACAN CULTURE JADE FACE WITH ITS RITUAL NOSEPLUG. It was 100% handcarved from a deep green Jade Stone Variety and he reiterates that…this is NOT an archaeological item.

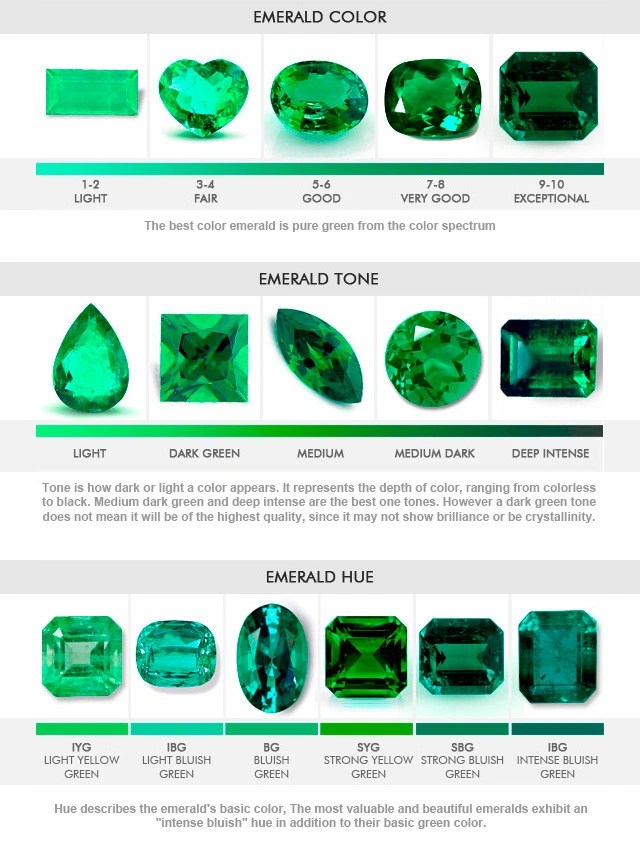

- Chalchihuitl is an Aztec word referring to a very valuable greenish stone. “Chalchihutil” was used for both jade and turquoise. “The Aztec gem stone chalchihuiil is jadeite, or its congeners diopside-jadeite and chloromelanite.” (Foshag 1955). CHĀLCHIHU(I)-TL precious green stone; turquoise / esmeralda basta (M), esmeralda en bruto (2), perla, piedra preciosa verde (S) Frances Karttunen, An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992)

- esmeralda basta, esmeralda en bruto = raw emerald/rough emerald

New word time. Congeners. I haven’t come across this word before (lack of education I guess. Sigh)

- con·ge·ner ˈkän-jə-nər kən-ˈjē- 1. : a member of the same taxonomic genus as another plant or animal. 2. : a person, organism, or thing resembling another in nature or action.

- A congener is a member of group of elements in the same periodic table group. Example: Potassium and sodium are congeners of each other.

- Congeners can refer to similar compounds that substitute other elements with similar valences, yielding molecules having similar structures. Examples: potassium chloride and sodium chloride may be considered congeners

- Congeners refer to the various oxidation states of a given element in a compound. For example, titanium(II) chloride (titanium dichloride), titanium(III) chloride (titanium trichloride), and titanium(IV) chloride (titanium tetrachloride) may be considered congeners.

- In chemistry, congeners are chemical substances “related to each other by origin, structure, or function”

- Congeners are substances, other than the desired type of alcohol, ethanol, produced during fermentation.

- The term “congener” refers to an individual compound within a family of compounds.

Same, same but different.

I mean, I did kind of have that figured myself. I do like to know things is all.

Chalchihuites

Matrícula de Huexotzinco is a census of the villages in the province of Huexotzinco

It has been pointed out by a reader that these circular “dots” on the base of Xochipillis statue (image above left) might be chalchihuites (although Wasson would have us believe they are representations of the “sacred mushroom” – other scholars i.e. Enrique Vela – identify them as other floral representations) and if this is the case then perhaps the same images on the back of the statue signify the same (?).

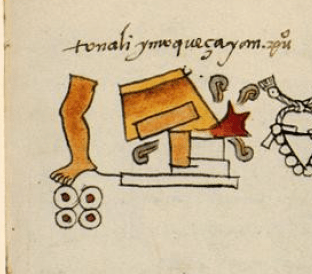

Pomedio (2005) notes of the statue of Xochipilli that “The tonallo symbol is present on the headdress of the statue and also on the base.” Gamio (1922) explains that the tonallo constitutes the lower part of the hieroglyph Tonallimoquezayan of the Codex Mendocino (1). He adds: “These words signify sun, day, heat, summer, and the sign is emblem of the deities of summer, vegetation, fertility.” We find on the upper edge of the base the basic unit of the tonallo symbol, that is, the chalchihuitl or green stone that represents the green precious stones such as jade and the different jadeites found in Mexico. (Pomedio 2005)

- Also called the Codex Mendoza

Frederiksen agrees in that “Xochipilli’s symbol “The Tonallo” is formed by four points signifying the heat of the sun.”

This understanding is further reinforced by Woods analaysis of glyphs in the Magliabecchiano Codex “This element for a day or the sun [tonalli) has been carved from a cloak featuring five flowers in the Magliabechi Codex.. This glyph for “day” is the central one of the five “flowers.” She also notes “how it compares favorably to the glyph for tonalli from the Codex Mendoza”. This element for a day or the sun appears on a page in the Magliabechi Codex where a cloak with a “Five Flower” design (Macuilxochitl) is featured. This glyph is one of the “flowers,” and yet it strongly resembles the tonalli hieroglyph from the Codex Mendoza.

Chalchihuitl or flores? Perhaps both

The chalchihuitl glyph takes many forms, often as a quincunx (1) formed by five circular glyphs..

- A quincunx is a geometric pattern consisting of five points arranged in a cross, with four of them forming a square or rectangle and a fifth at its centre.

Emerald, precious stone

(here, attested as a man’s name)

(here, attested as a man’s name)

Bernal Díaz describes the chalchihuitl as “a species of green stone of uncommon value, which are held in higher estimation with them than the smaragdus (1) with us”.

- this likely refers to the gemstone known as an emerald (it can also refer to the beryl and jasper gemstones)

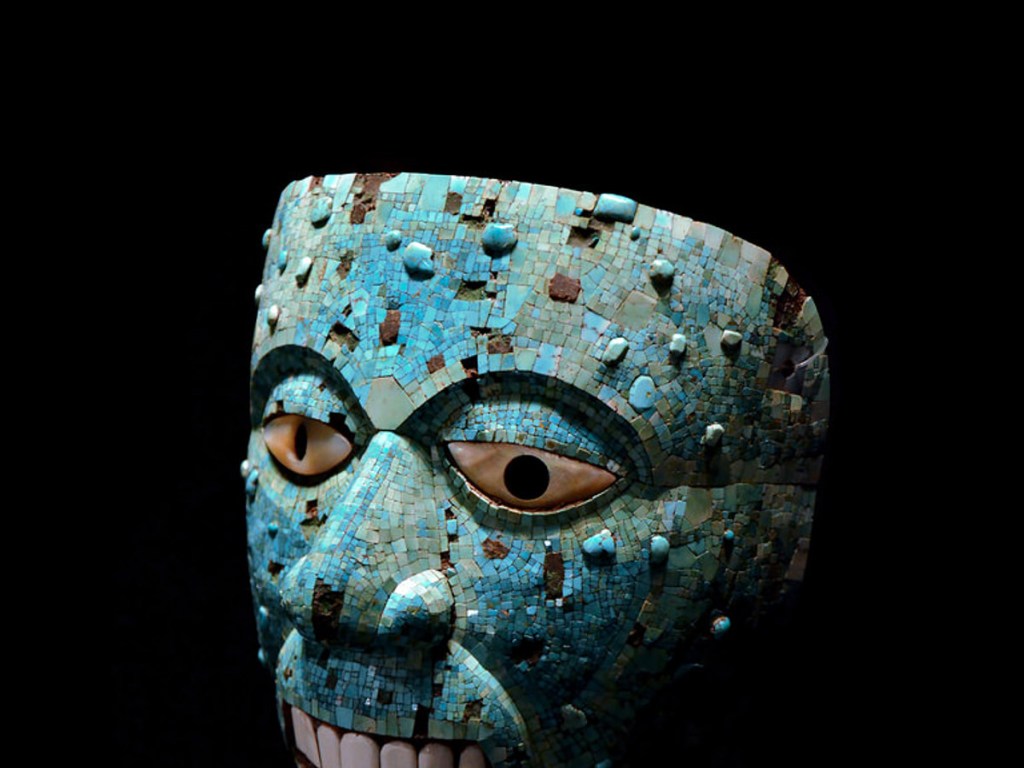

Mason (1927) notes there being an issue with the distinction between the chalchihuitl and turquoise. “The Spanish were familiar with turquoise and were able to identify that gem by name, but jade was apparently unknown in Spain, or at least to the ordinary Spaniard, and he could not refer to it by other than the native term.” He also notes that consensus suggests that chalchihuitl was the name given to turquoise in the areas it was mined (far north of Tenochtitlan in the area now called New Mexico) but in the lands of the Mexica this stone was called “xihuitl”, which according to my handy dandy Nahuatl dictionary…….

xihuitl.

Principal English Translation:

turquoise; herbs (sometimes psychedelic) and other greenish things, such as grass, greenstone

Xiuhtecuhtli is an “old” god. Not only in age but from an older pantheon of Mesoamerican gods. He is a god of fire and of time. The word xihuitl not only translates as “turquoise” but also “year” (which is where the associations with time arise). He is often also equated with an older old god of fire, Huehueteotl, who is sometimes referred to as Huehuetéotl-Xiuhtecuhtli.

“huehue “denotes not just old but “old old” and “teotl” denotes a divine or sacred force; a deity; divinity; God; something blessed, something divine. Huehuetéotl-Xiuhtecuhtli was associated with ideas of purification, transformation, and regeneration of the world through fire. As the god of the year, he was associated with the cycle of the seasons and nature which regenerate the earth. He was also considered one of the founding deities of the world since he was responsible for the creation of the sun. (Limón Silvia 2001) (Matos Moctezuma 2002)

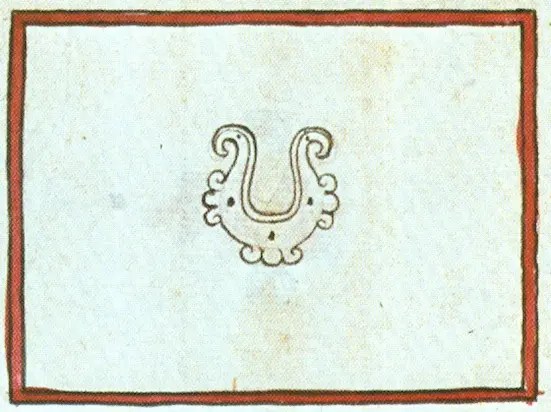

The yacaxihuitl or turquoise nose ornament (yacatl = nose and we’ve just gone over xihuitl a little so I probably don’t need to repeat myself)

This has been an interesting diversion (my mind does this quite frequently) so lets get back to the mask.

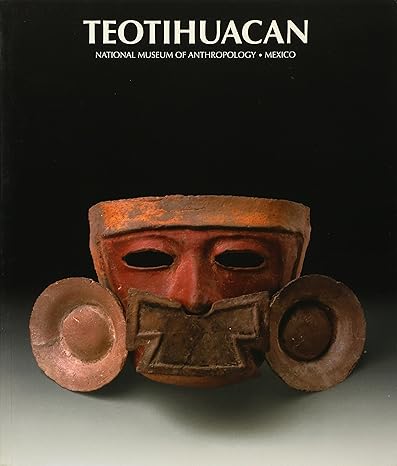

(Image below) San Francisco Mazapa. Theater-type censer. Taken from the “Museo de Murales Teotihuacanos Beatriz de la Fuente”. Teotihuacán, Mexico, 2007

The so-called “theatre-type” censers belong to the group of most emblematic objects from Teotihuacan. They began to be manufactured in the Tzacualli phase (between 1 and 100 AD).

The eBay seller “green jade stone” pendant referred to the below image on his site.

This object is mirrored by another I have in my collection.

The above image is of a mask that was “gifted” to me by a Mexican amiga Eugenia. It was a bit of a joke actually as she found the object hideous and didn’t care for it being in her house (so she gave it to me). Jokes on her really because I love it (and its tenuous links to Xochipilli make it all the more valuable in my eyes)

The nasal ornamentation is very interesting.

Enrique Vela notes that amongst the body modification practices of prehispanic mesoamericans that the use of nose rings (narigueras) was reserved for the elite; “at least from the Classic period onwards, the piercing of the nose necessary for its placement was carried out as part of a ceremony that was intended to invest a sovereign, who on that occasion received insignia that would henceforth symbolize his condition as ruler, including the nose ring.”

McEwan and Lopez Lujan (2009) note that “During the investiture (of the Tlatoani), the septum of the new sovereign was also pierced with the help of a jaguar bone awl; a tubular nose ring called a xiuhyacámitl was placed there.

Castillo (2022) also relates of Motecuhzomatzin that the nose ring (xiuhyacámitl), as a symbol signified him as being a great lord par excellence.

- xiuh-.

Principal English Translation:

a prefix that refers to a blue-green color, or something turquoise - -yacamitl.

Principal English Translation:

very thin nose plug (literally, nose arrow) (Olko); or, a nose rod (Sahagún)

xiuhyacamitl = “and then they pierced the little nose bone and put a small and delicate piece of very thin emerald in it” (Tezozomoc 1949)

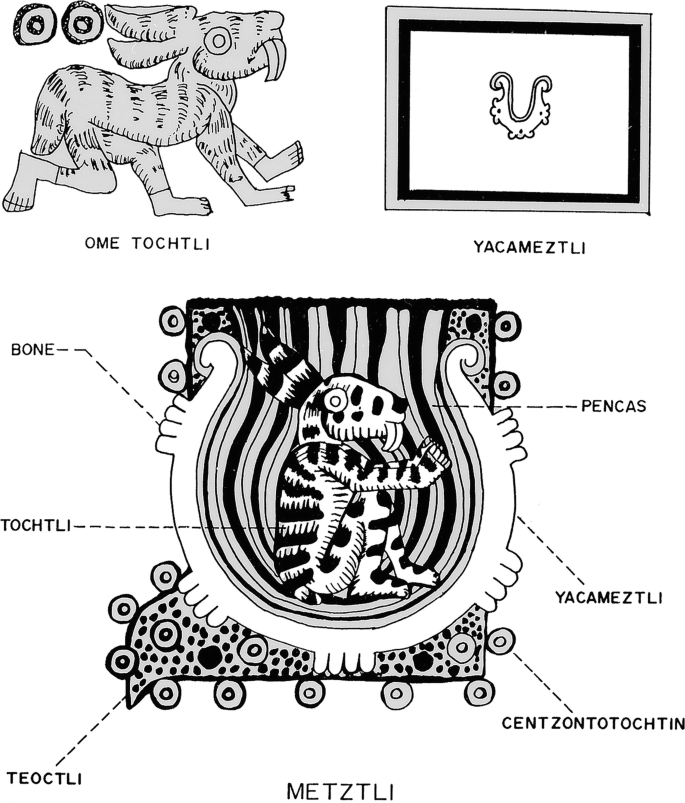

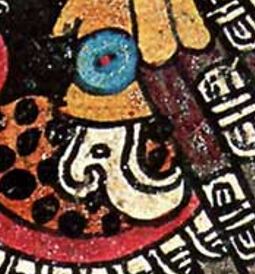

Yacameztli or “lunar nose ring” (in Nahuatl : yacatl = nose and meztli = moon), was a facial ornament in the shape of a nose ring with a crescent moon with the edges curved outwards, which symbolized the natural relationship with fertilization and the growth of nature.

In the Mesoamerican pantheon, the gods who carried yacameztli such as Mayáhuel , Patécatl , Tlazolteolt or the Centzontotochin were associated with the natural forces of creation and fertilization, but also with those of death and regeneration. For more information on these beings see Mayahuel and the Cenzton Totochtin.

(Olivier 2020).

Codex Fejérváry-Mayer.

Codex Laudianus

Codex Borgia

Chalchiuhtlicue (she of the green stone skirt) was a patroness of birth and her powers lay close to running waters. In Aztec imagery her skirt was made of jade stones from which water often flowed. To the Azteca she was the goddess of fertility, bodies of water like seas, rivers, and lakes as well as of flowing water in general.

The yacapapalotl or butterfly nose ornament

YAC(A)-TL nose, point, ridge / nariz, o punta de algo (M) T and X have YE for YA.

Frances Karttunen, An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992)

PĀPĀLŌ-TL pl: -MEH butterfly / mariposa (M).

Frances Karttunen, An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992)

Terracotta mask : Teotihuacan : Early Classic (150-300 A.D.) : Teotihuacan, State of Mexico : Clay with red, black, yellow and white pigments : National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico.

The lack of expression and the standardized features of this mask make it purely Teotihuacan in style. It is unusual, however, in that it is not made of stone, but of baked clay, and also in that it includes other elements commonly found in painted depictions of masks but not in actual masks found so far, to wit: the “butterfly” nosepiece motif and the disc ear flares. Nosepieces as emblems of power have a long history in Mesoamerica

These Teotihuacan masks are generally related to funerary (1) rituals. Various statements have been made regarding these masks such as that these masks “were likely attached to the bundled remains of important individuals” because these “Mortuary bundles perhaps served as oracles through which revered ancestors imparted knowledge to their living descendants, the mask being the conduit between the deceased and the living” or that “the mask (this mask in particular) was probably not worn in rituals due to the shape and weight of the work. Rather, it appears likely that it would have been a “death mask” placed over the face of elite individuals and attached through holes in the work’s ears to prepare them for their journey to the afterlife”. There is a goodly amount (perhaps not unwarranted though) of supposition being made in these statements that unfortunately doesn’t really illuminate the subject.

- the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect the dead, from interment, to various monuments, prayers, and rituals undertaken in their honour.

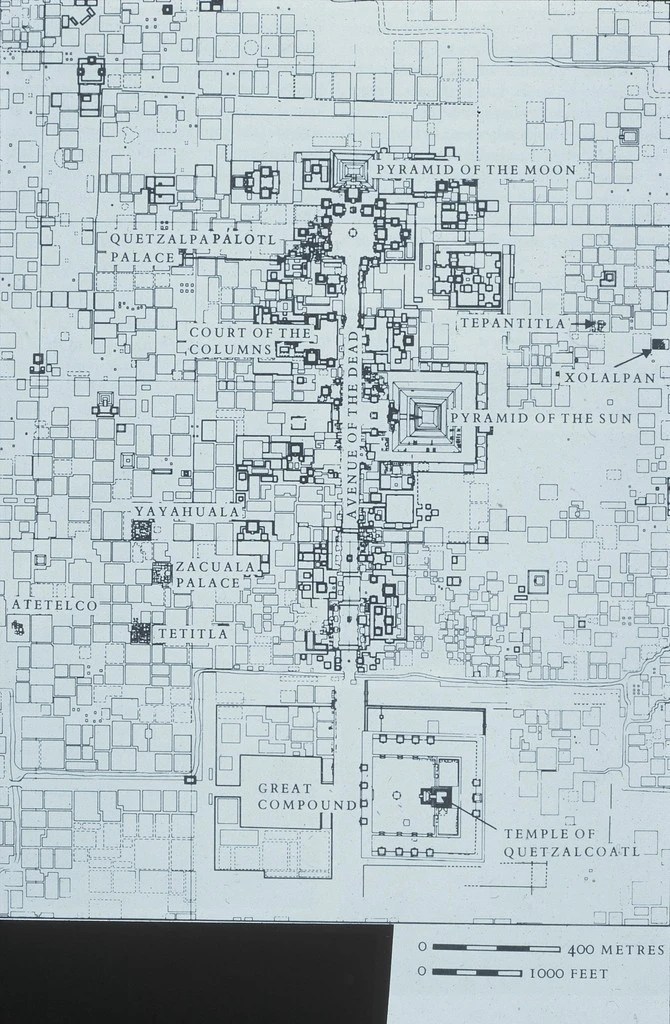

The Teotihuacan society is somewhat tenebrous (shadowy, obscure) as, much like the name Olmec, they likely did not identify themselves by this name. Teotihuacan society was already long in ruins by the time the Mexica passed through the area and the name Teotihuacan itself is a Náhuatl word (possibly) meaning “the place where men became Gods” (1)

- from Nahuatl Teōtīhuacān possibly from teōtī(uhtli) (elder god) + -huah (owner/possessor of something) + -cān (place of) meaning “At the place of the owners of the elder gods,” per J. R. Andrews’ “Introduction to Classical Nahuatl”.

I also have in my collection an obsidian representation of a carving from the Pyramid of Queztalcoatl which I purchased from an artisan selling his wares to tourists in the grounds of Teotihuacan.

Central Mexico, Teotihuacán, Classic period

Currently at the Cleveland Museum of Art

These Teotihuacan masks – with holes for tying them – are believed to have been used for funerary purposes, but none have been found on a deceased person. National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City. (Moragas Segura 2024)

Teotihuacan Mexico.

Circa 600 – 900 A.D

The Walters Art Museum

Baltimore Online Collection

The more I look the less I believe the mask at the heart of this post to be that of Xochipilli

I have seen it noted that “Xochipilli may have origins in the earlier Mesoamerican god worshipped at Teotihuacán during the Pre-Classic to Classic Period who is known simply as the Fat God” (although this oft repeated statement is at this stage without specific references) and that “Many archeologists (sic) believe he was first worshipped during the years of the Teotihuacan civilization, but was later adopted by the Aztecs.” (again, still seeking references). The butterfly imagery is compelling (but by no means definitive) but again it should be noted that Teotihuacan was a long dead civilisation by the time the Mexica came tromping through the lands of Anahuac so even though they may have been inspired by and even adopted aspects of what they found it was merely through inspiration rather than any direct knowledge of the culture.

Although the focus of this Post is more on the nasal ornamentation rather than that of the ears I would like to bring up a comment made by a reader on a previous Post Xochipilli. The Symbolism of Enrique Vela.

In this Post “orejeras” were brought up. A literal translation of this word is “earmuffs” but, as Nati mentioned, the more correct terminology would be that of would that of “earplug” (nacochtli). According to the Nahuatl dictionary this can be further classified into ear plugs (more prestigious) or ear flares (less prestigious). Molina and Sahagun further delineate these modifications into more specific categories.

teocuitlanacochtli = golden earplugs (especially prestigious)

xiuhnacochtli = turquoise earplugs (equally prestigious);

mayananacochtli = green june beetle earplugs (no image found)

itznacochtli = obsidian earplugs (more common, less prestigious);

Aztec jewellery in Museo del Templo Mayor

cuetlaxnacochtli = leather earplugs (awarded to warriors of the higher ranks) (no image found)

Below are some images of ear ornamentation of warriors chronicled in various codices.

quetzalcoyolnacochtli = quetzalli-coyolli-nacochtli = curved green ear pendants with bells (green shell-shaped ear pendant) (given to pochteca who participated in a conquest)

Ear plugs and flares

Among the Mexica, ear piercing was done during childhood and had a ritual background; according to Friar Bernardino de Sahagún, this occurred during one of the two movable festivals that were held every four and eight years: “In the one that was done every four years, the ears of boys or girls were pierced and the ceremonies of “crezca para bien” (grow well) were performed” (Vela)

Once every four years parents brought their children forward in a public ceremony. The children who had been born within the previous four years were held over a fire to be purified and would have their ears pierced and a cotton thread was inserted. The hole in the ear would gradually be expanded as the child grew, so that by the time of adulthood an ear ornament of up to 2 cm could be accommodated. (Joyce 2000)

References

- Alvarado Tezozómoc, Fernando. 1949. Crónica Mexicayotl. México: Impr. Universitaria.

- Beyer, Bernd. (2013). El “corazón del monte” entre los zapotecos del posclásico. Anales de Antropología. 47. 9-29. 10.1016/S0185-1225(13)71004-X.

- Butterfly Nose Ornament|url=https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1990.263.2|author=|year=150–200 CE|access-date=12 September 2024|publisher=Cleveland Museum of Art}}

- Castillo F., Víctor M. 2022. «Relación Tepepulca De Los señores De Mexico Tenochtitlan Y De Acolhuacan». Estudios De Cultura Náhuatl 11 (noviembre):183-225. https://nahuatl.historicas.unam.mx/index.php/ecn/article/view/78490.

- Cleveland Museum of Art (Mask) – https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1921.1701

- de Molina, Alonso : Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, 1571, part 2, Nahuatl to Spanish, f. 062v. col. 1.

- de Sahagún, Fr. Bernardino : Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain; Book 6 — Rhetoric and Moral Philosophy, No. 14, Part 7, eds. and transl. Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble (Santa Fe and Salt Lake City: School of American Research and the University of Utah, 1961)

- de Sahagún, Fr. Bernardino : Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain; Book 8 — Kings and Lords, no. 14, Part IX, eds. and transl. Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble

- Foshag, William F., “Chalchihuitl – A study in jade,” American Mineralogist, vol. 40, nos. 11-12,

- 1955, pp. 1062-1070.

- Hawksworth, D. L. (2010). Terms Used in Bionomenclature: The Naming of Organisms and Plant Communities : Including Terms Used in Botanical, Cultivated Plant, Phylogenetic, Phytosociological, Prokaryote (bacteriological), Virus, and Zoological Nomenclature. GBIF. ISBN 978-87-92020-09-3.

- IUPAC (1997). “Congener”. Compendium of Chemical Terminology (the “Gold Book”) (2nd ed.). Blackwell Scientific Publications. doi:10.1351/goldbook.CT06819

- Joyce, Rosemary (2000) “Girling the Girl and Boying the Boy: The Production of Adulthood in Ancient Mesoamerica,” World Archaeology (2000): 473-84.

- Limón Silvia, 2001, El Dios del fuego y la regeneración del mundo, en Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, N. 32, UNAM, Mexico, pp. 51-68.

- Mason, Dr. J. Alden. “Native American Jades.” The Museum Journal XVIII, no. 1 (March, 1927): 47-73. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.penn.museum/sites/journal/8950/

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo, 2002, Huehuetéotl-Xiuhtecuhtli en el Centro de México, Arqueología Mexicana Vol. 10, N. 56, pp 58-63.

- Mayahuel – Codex Borgia – By Desconegut – Aquesta imatge ha estat creada amb Adobe Photoshop., Domini públic, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24708281

- Mayahuel – Codex Fejérváry-Mayer. – Door Goncalves de Lima, Oswaldo – Goncalves de Lima, Oswaldo. El maguey y el pulque en los codices mexicanos, page 136. Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Economica, 1956., Publiek domein, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1097817

- Mayahuel – Codex Laudianus – http://www.famsi.org/research/pohl/jpcodices/laud/img_laud09.html

- McEwan, Colin, and Leonardo Lopez Lujan (eds.) (2009) La exposición Moctezuma : Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia : ISBN: 978-607-484-110-7

- Mendoza, R.G. (2024). The Harvest of Souls: Mimesis, Materiality, and Ritual Human Sacrifice in Mesoamerica. In: Mendoza, R.G., Hansen, L. (eds) Ritual Human Sacrifice in Mesoamerica. Conflict, Environment, and Social Complexity. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-36600-0_8

- Millon, René & Altschul, Jeffrey. (2015). THE MAKING OF THE MAP: THE ORIGIN AND LESSONS OF THE TEOTIHUACAN MAPPING PROJECT. Ancient Mesoamerica. 26. 135-151. 10.1017/S0956536115000073.

- Moragas Segura, Natalia (2024) https://historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/teotihuacan-ciudad-piramides-mas-grandes-mesoamerica_19576

- Olivier, Guilhem. (2020). BLOOD, FLOWERS, AND POWER: A NEW INTERPRETATION OF PLATE 44 OF THE CODEX BORGIA, A MEXICAN PRE-HISPANIC MANUSCRIPT. Ancient Mesoamerica, (), 1–16. doi:10.1017/S0956536119000336

- Olko, Justyna (2005) Turquoise Diadems and Staffs of Office: Elite Costume and Insignia of Power in Aztec and Early Colonial Mexico (Warsaw: Polish Society for Latin American Studies and Centre for Studies on the Classical Tradition, University of Warsaw)

- Vela, Enrique, “Orejeras”, Arqueología Mexicana, edición especial núm. 37, pp. 68-75.

- Vela, Enrique, “Narigueras”, Mexican Archaeology , special edition no. 37, pp. 82-87.

- Yacameztli o yacapapalotl (image) via Quetzaltonatiuh on Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/Culturaprehispana/posts/yacameztli-o-yacapapalotlnariguera-lunar-o-nariguera-de-mariposaesta-nariguera-e/105330174301458/