the order in which I obtained them

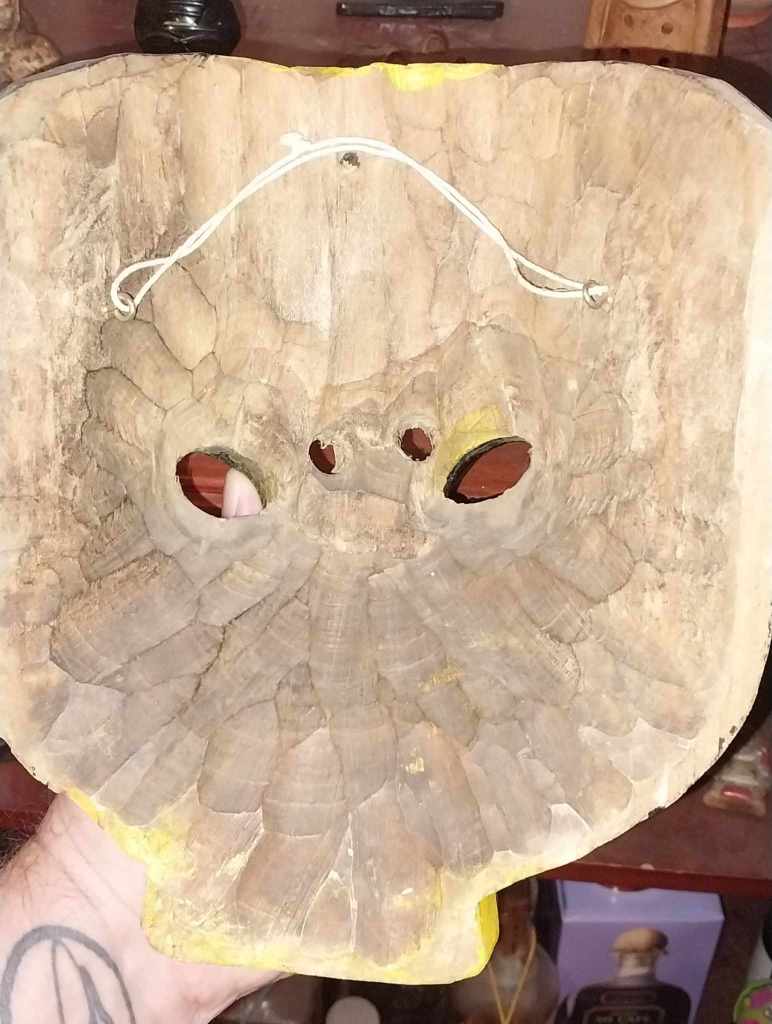

This was the first mask to enter my collection. To be honest I didn’t know it was Mexican when I purchased it, I just really liked the style and colour. I’m still not entirely sure it is Mexican although there are hints that lead me to believe it is (more on this in a little). All of the masks I own have been purchased second hand with most being found at either Good Sammies (Good Samaritans) or Salvo’s (Salvation Army) thrift stores. I have had some luck on Facebook Marketplace and I’ve picked one up from eBay. I tend to avoid purchasing from eBay as it takes some of the adventure out of the whole process (which I see as a form of Urban Archaeology) as you can pretty much purchase anything from anywhere and you lose the excitement of discovery.

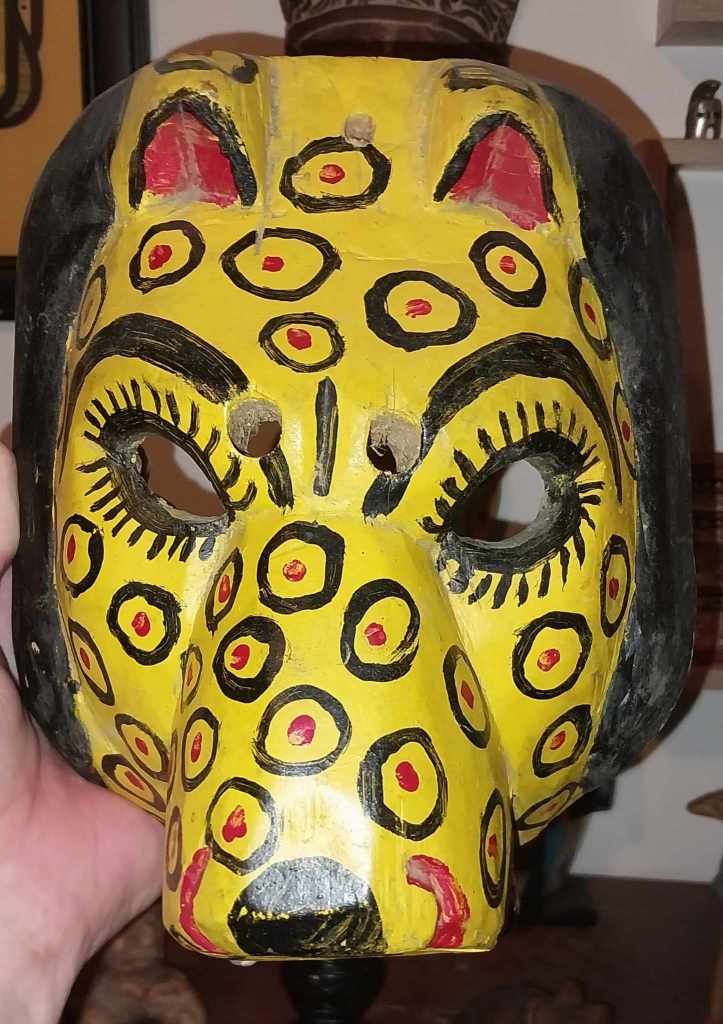

This wooden mask is reminiscent of the tigre (jaguar) masks of Guerrero. The use of jaguar masks is common in dances across many different ethnic groups in the Guerrero region, including el danza de los Tlacololeros, the danza de los Tecuanes, la danza del Tigre y los Tlaminques, and the famous danza de los Tigres de Zitlala (although these last ones are usually full head covering, helmet like masks made of leather).

examples of such masks from the Guerrero region

(on the border of Guerrero and Oaxaca)

The next set of images is of a mask that can be found in the Roma Arellano online store (1). It gives me some indications that the mask in my collection is Mexican. The eye holes (and another set of holes drilled just above them) and the rear of the mask are similar in many respects to the one in my collection. My mask even came with a similar piece of twine for hanging (although I have since removed and replaced this)(see images below).

(the name of the store, not the artisan)

A comparison of the mask in my collection

I did note that this was the first mask to enter my collection but I should make one caveat and that being it was the first Mexican mask to enter the collection. I do have a number of other masks from a number of other cultures adorning the walls of my abode. I’m not entirely sure what the attraction is but I am drawn to masks and am particularly fond of carved wooden ones. The bulk of my collection is Balinese (with a couple from other parts of Indonesia). I also have masks from several regions of Africa, Asia (including Thailand and Vietnam), Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Sri Lanka, Tibet, Nepal, France and regions unknown. Most of my masks are made of wood but I also have several other clay/ceramic/terracotta/plaster ones (and even one made from concrete) as well as a few made from papier-mâché.

A small selection of my collection

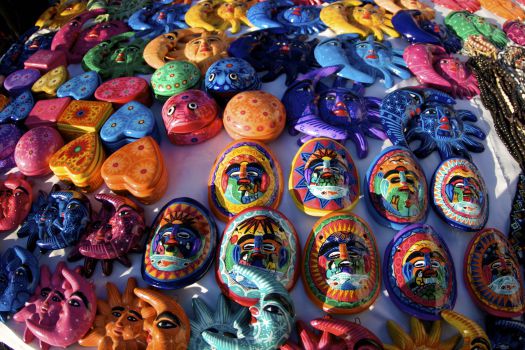

The mask shown below is much smaller than it appears in the photo (about 10 x 12cm / 4 x 5 inches). It is made of glazed and painted terracotta (and only cost me $2 – quite the bargain). These seem to be quite common tourist purchases. I have not been able to determine if they belong to a specific region either via their medium (terracotta), their style of glazing, or the imagery on the masks.

These masks are common and seem to have been around for a while.

All of my masks have been sourced in Australia. Part of the attraction to these masks is that they have been produced in locations far-flung from the shores of Australia and I like to ponder upon the set of circumstances that led to the mask now being in my hands. Who made it? When was it made? Where was it made? How did it get here? Who owned it before me? Why did they give it up? It might be the young boy in my heart but I do love an adventure story (and a treasure hunt). Many of these questions remain unanswered. The vast majority of the people I have sourced masks from have been unable to even tell me where the mask was initially purchased let alone who the artisan who created it might have been.

The mask above is a wooden replica of a Teotihuacan style mask. This one was gifted to me by a Mexican amiga who had it in her house but REALLY did not like it. She thought it to be quite hideous so she gave it to me. Jokes on her really as I love it and what it symbolises (or potentially symbolises). The mask had been in the family for quite some time and was in boxes of stuff that was carted around to be used in displays set up by FOMEX : The Friends of Mexico Society. It was however never used and always remained in its box. Then one fine day it passed into my eager hands.

The green “T” shape that covers the mouth is a butterfly shaped nose piercing/ornament called a yacapapalotl (yacatl = nose : papalotl = butterfly : alternatively a “nariguera” or nose-ring). It has been said (although I tend to think this erroneous) that this mask is representative of the being known as Xochipilli (there is little doubt though that nasal ornamentation is connected to Xochipilli). I go into a lot more detail on the mask in my Post….Mascara de Xochipilli?

These Teotihuacan style masks are posited to be funerary in nature. This is largely speculative though as the Teotihuacanos were long dead by the time the Mexica came tromping through the valley of Mexico. Even the name of their city “Teotihuacan” was made up. In Nahuatl (the language of the Aztec) it (roughly) translates to a number of things from “birthplace of the Gods” (Jiménez 2024), “the place where the Gods were born” (Snow etal 2020) “at the place of the owners of the elder gods” (Beidler & Andrews 1975) or “the place where men become Gods” (Cowgill 2015)

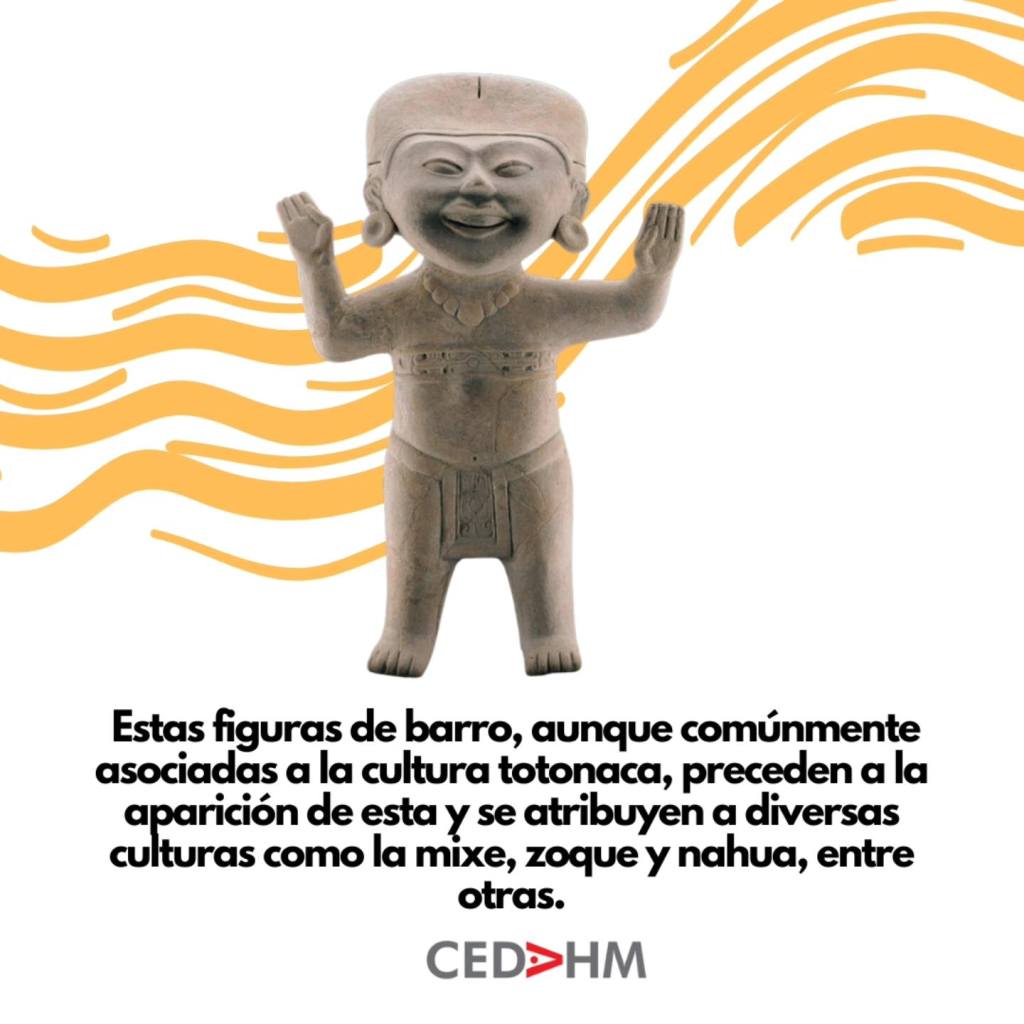

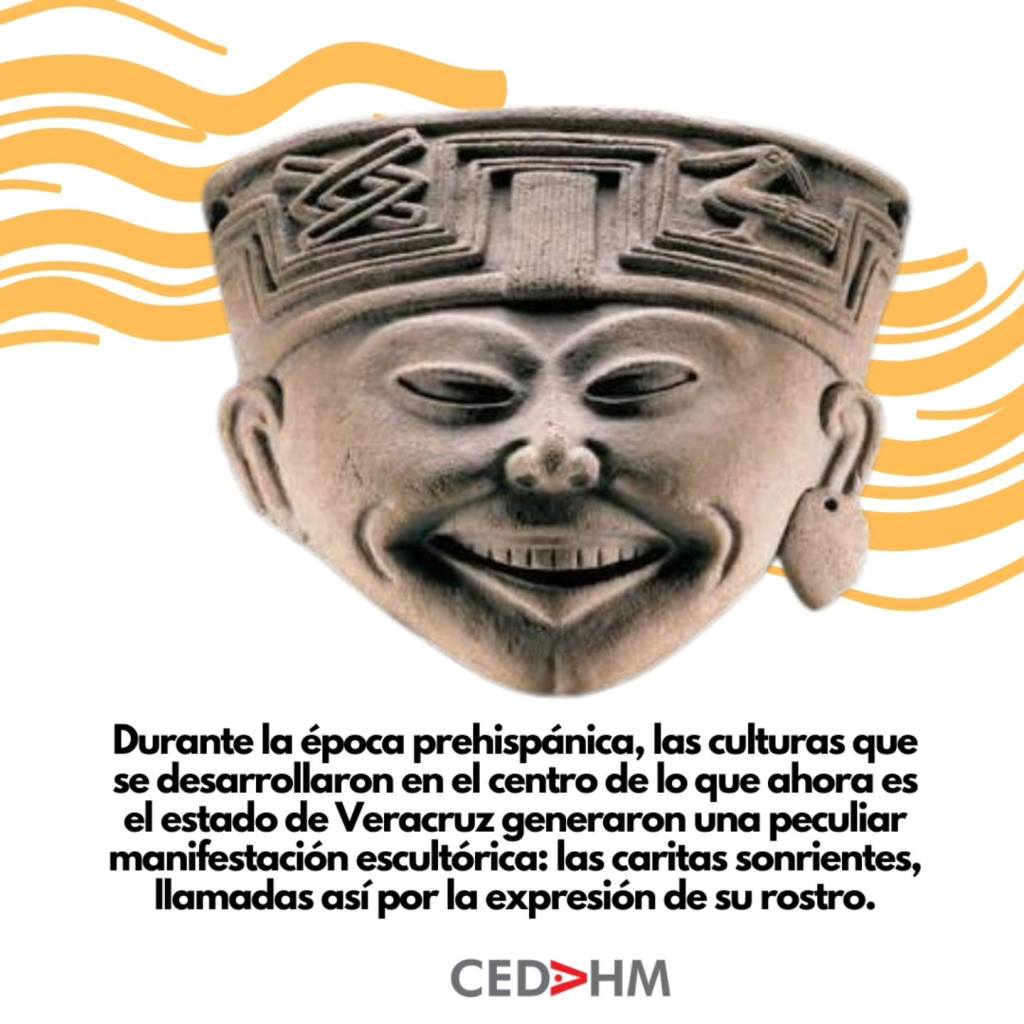

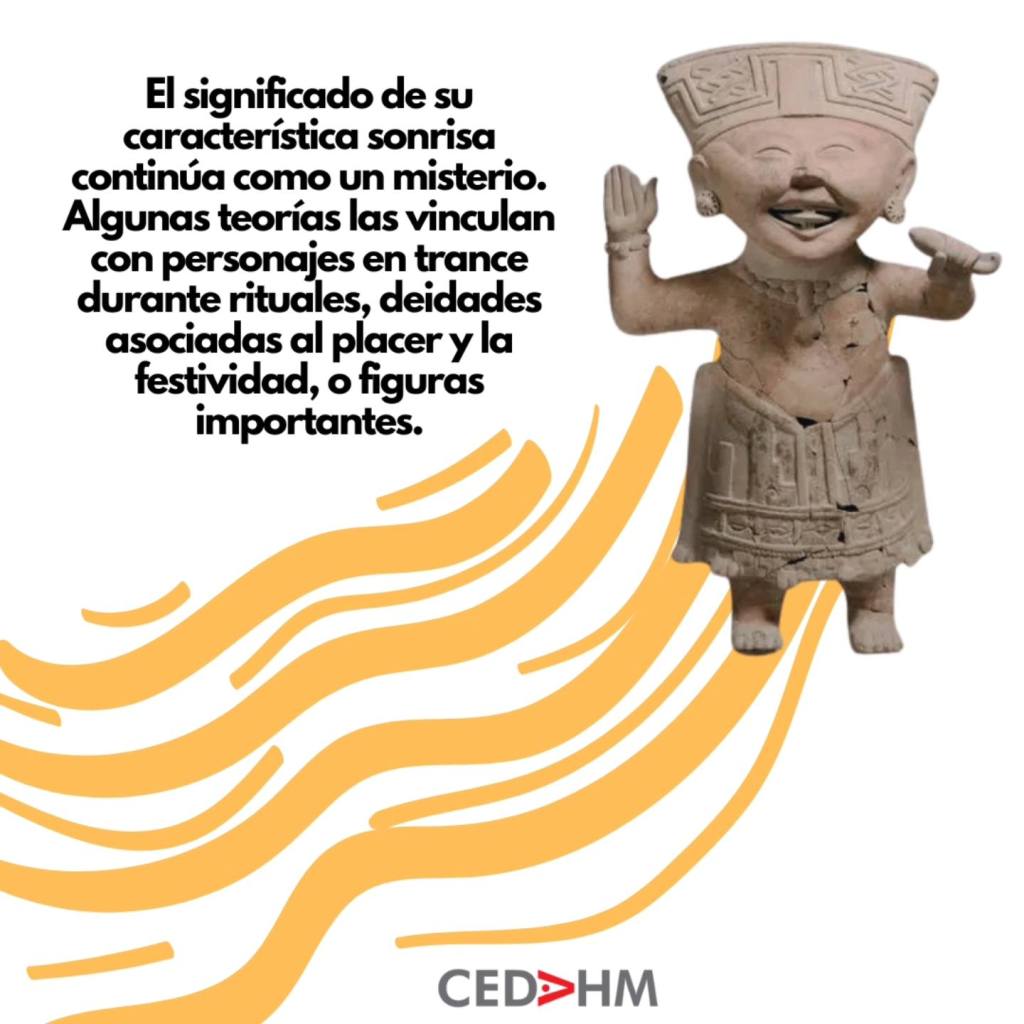

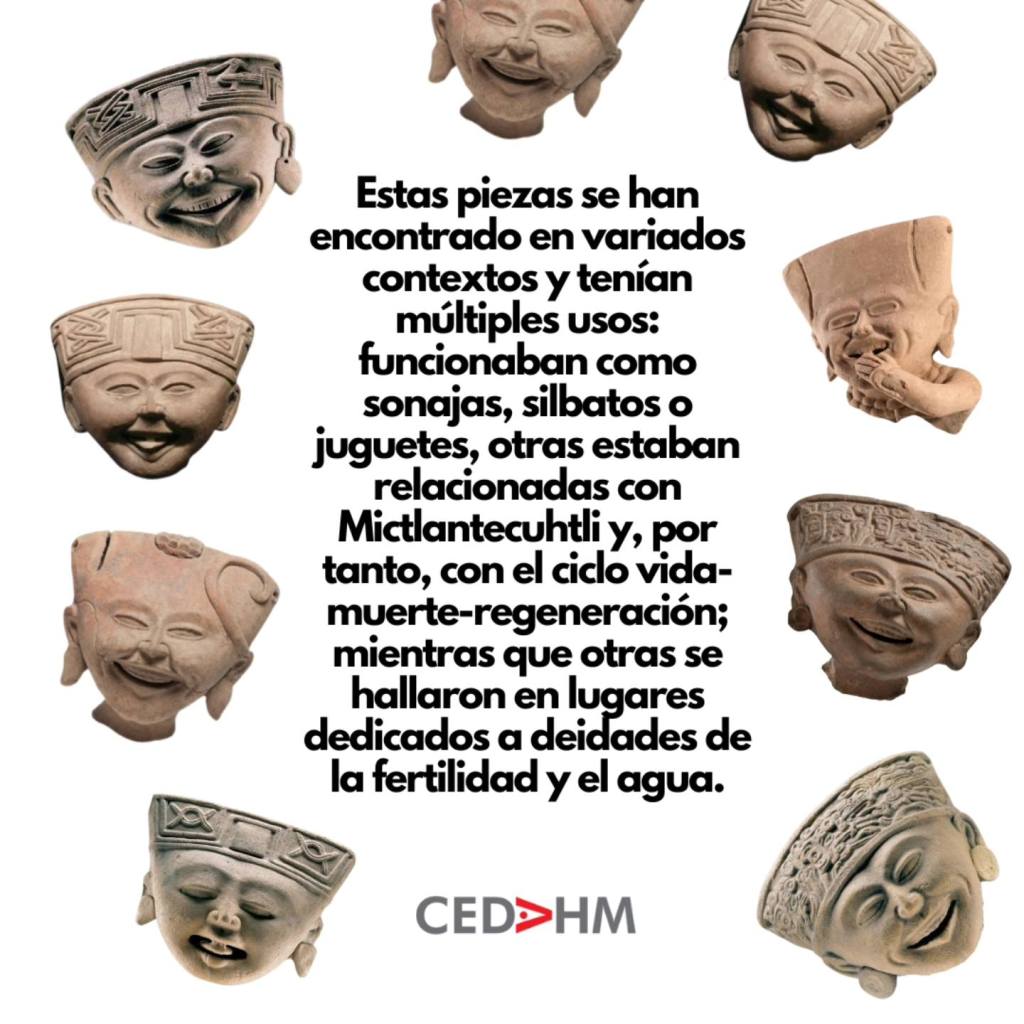

This mask is the only one (so far) that I have purchased on eBay. It is a replica of the face of a sonriente (smiling) terracotta figure from the Veracruz region of Mexico. These smiling figures (which are quite unusual in mesoamerica) are typical of the Remojadas culture (which is also the name used to denote both the artistic style of these terracotta figures and archaeological site in which they were discovered) which is posited to have flourished on the Veracruz Gulf Coast of Mexico circa 100BC to perhaps 800AD. Researchers have described the faces as portraying drunken (on pulque) or hallucinating (on mushrooms) people; others say they relate to cults of the dead or more prosaically that they simply represent smiling performers of one variety or another.

Inlaid stone mosaic masks. Often said to be burial masks. I’ve seen them called Mayan, Teotihuacano, Oaxacan, Aztec (the list undoubtedly goes on). These are standard tourist fare.

I found both of these masks on Facebook Marketplace.

Masks from the lands of the Maya

I investigate this mask in my Post Máscara Maya? Mayan Mask?. I purchased it (and another similar one – next mask down) from the same buyer (again through Facebook Marketplace). These ones cost me $20 a piece (if I remember correctly – it’s been a while). They are again fairly standard tourist fare most likely from the lands of the Maya. I have seen a lot of this style of mask made from carved wood but this one appears to be made from some kind of ceramic/porcelain material. A damaged section on the right ear shows the mask to be made from a white ceramic material.

Another example of tourist fare, this time common in the regions of the Maya

These are the largest masks in my collection. Each is about 30cm (1 foot) tall.

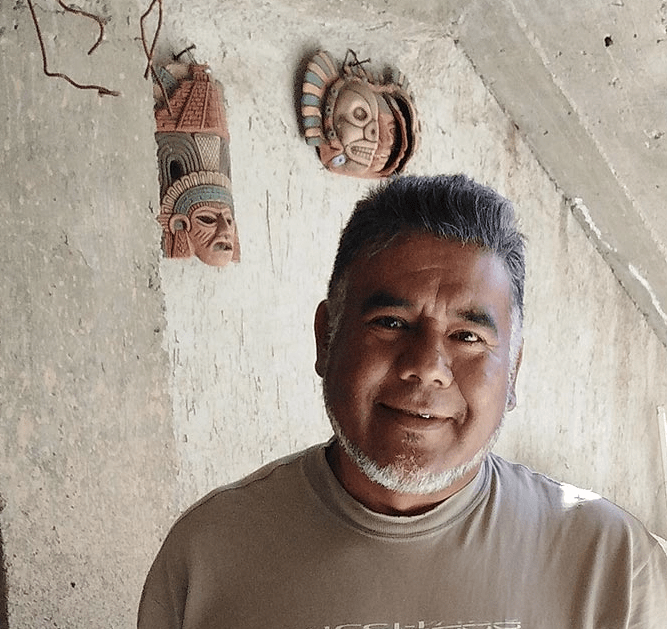

This next one excited me to no end. Another Facebook Market place find and at a bargain price. The seller had no idea what it was

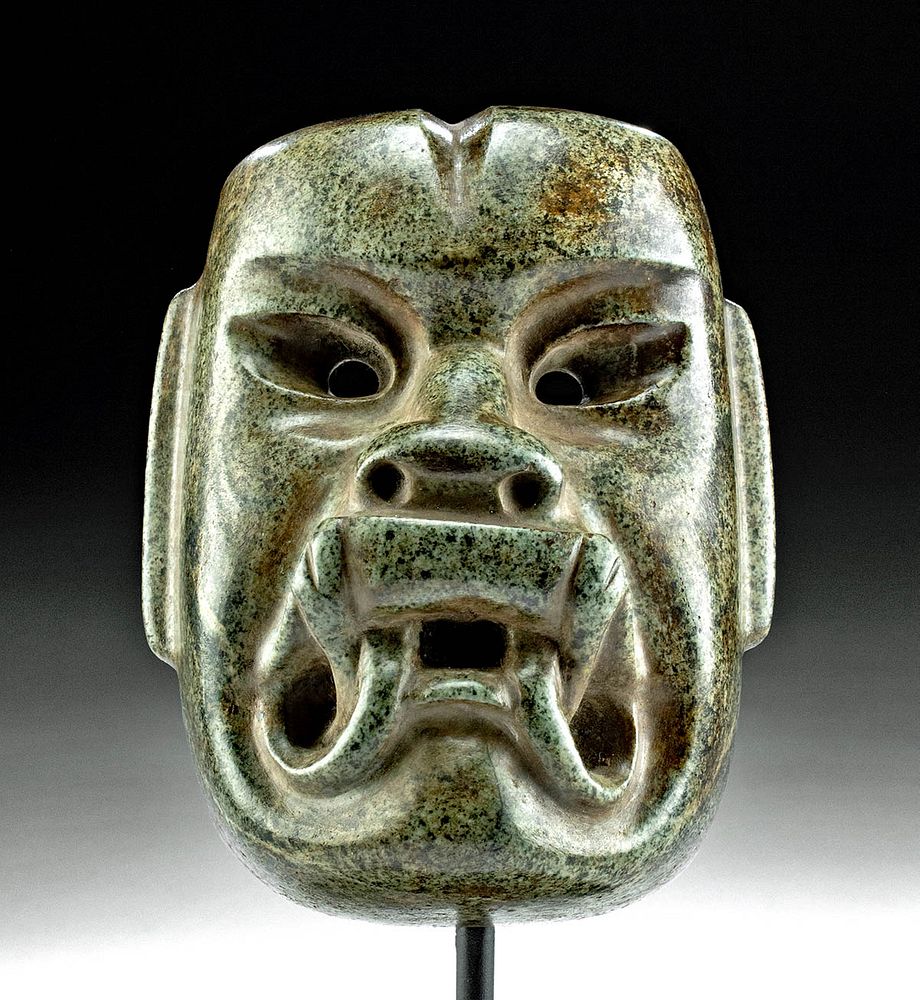

This 10cm x 6 cm (about 4 x 2.5 inch) serpentine replica of an Olmec carving was a score. I myself didn’t know what it had been carved from and had to consult a gemstone expert for this information.

The pierced ears (more noticeable from the reverse side) also lead me to believe that it once wore ear-rings of some variety

I wear it on a gemstone necklace. It draws much attention (particularly from New Zealanders).

In New Zealand a jade like stone is highly valued. Pounamu (also called New Zealand jade or greenstone) is used to describe several types of (mostly) green-hued durable stone found in only a few locations in southern New Zealand. Pounamu jewellery is typically carved into traditional Māori symbols. More than just a beautiful art form, pounamu can represent ancestors, connection with the natural world, or attributes such as strength, prosperity, love, and harmony. It was traditionally gifted on important occasions as a symbol of honour, respect, and permanence – reflecting the esteem in which the gift giver held the person or group they were making the gift.

The gemstones for the necklace were fortuitously scored at another thrift store about two weeks later for the princely sum of $7.

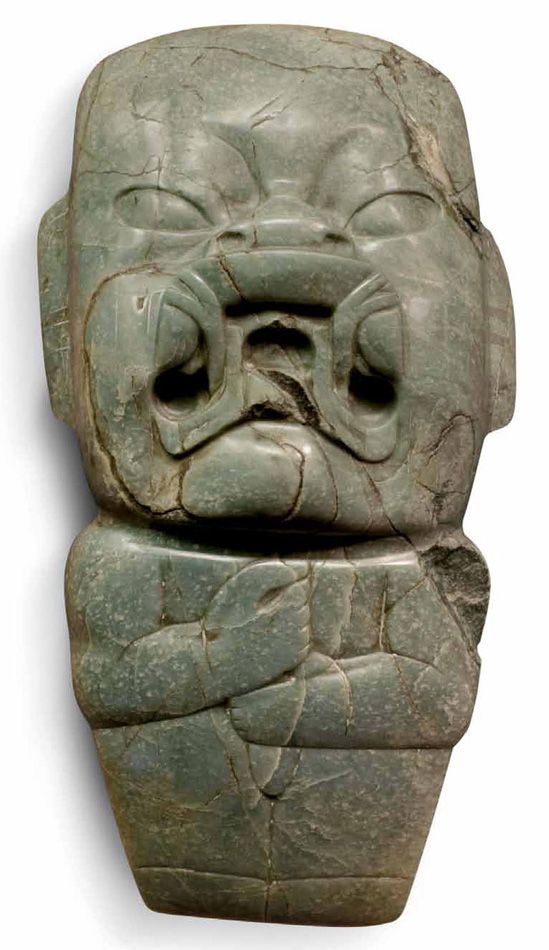

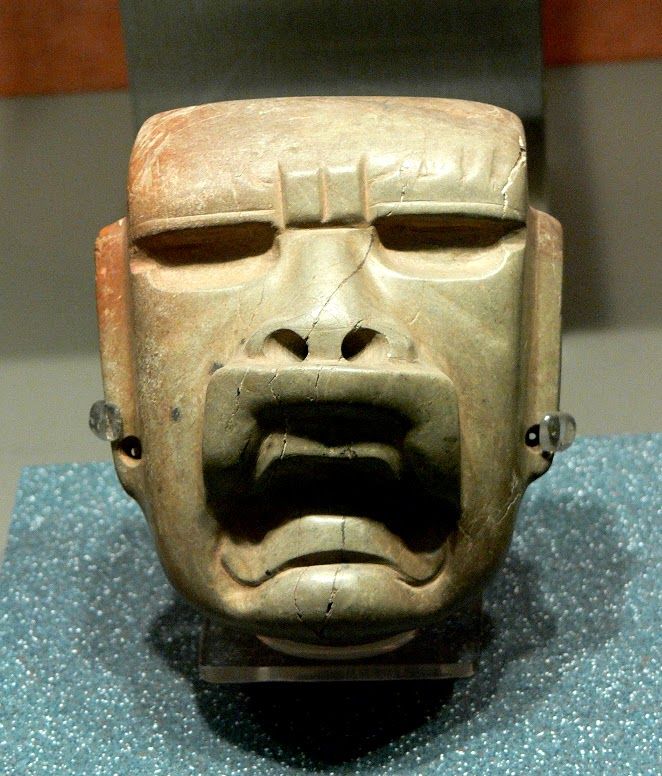

The Olmec (much like the Teotihuacanos) were likely not known by this name. Olmec is a designation that means “people from/ inhabitants of the land of rubber” generally thought to be derived from the Nahuatl “olli” (rubber).

They are well known for the creation of “colossal” stone heads which general consensus tells us were buried some time around 1000 – 900BC

They were also consummate artisans and created many beautiful jade masks.

An interesting type of mask attributed to the Olmec was the one called a “were jaguar” (yep, just like a werewolf but a jaguar). Much theorising exists as to what these masks were created to illustrate from “the dominance of the ruling classes” (Slater 2010) to “shamanic transformation” (Furst 1995) “the exemplification of Down Syndrome” (Milton & Gonzalo 1974) or other “congenital birth defects” (Murdy 1981) or even “the result of interspecies sex between a human female and a jaguar” (Stirling 1968).

Were Jaguar “axes”

Were Jaguar Masks

The next couple of masks were a Facebook score.

These masks are quite heavy and made of painted plaster. They were part of set of three masks. I was too slow and missed out on mask number 3.

I did however find an excellent statue of a Yaqui deer dancer amongst the same sellers treasures.

This dark greenstone carved mask (pendant) is about 8cm (3 inches) wide and was gifted to me on my birthday in 2024. It is a replica of the carved wooden Teotihuacano mask mentioned at the start of this Post. I go into a lot more detail on the mask in my Post….Mascara de Xochipilli?. I am now seeking a beaded obsidian chain for it.

A smooth polished black clay mask which I found at a Red Cross thrift store (in Western Australia). This was another mask I purchased (for only $4) without knowing its provenance. It ‘felt” Mexican to me. Queries through Mexican Folk Art pages that I follow on Facebook confirmed that is is in fact Mexican (possibly Oaxacan). It is again smaller than it looks and fits neatly in my outstretched hand.

In an oddly spooky and synchronistic turn of events the exact same mask is currently available on eBay (as of 9th September 2024). The item is being sold by an American Red Cross store located in Alsip village in Cook County, Illinois, United States. They do not however offer any more clues as to the origin of the mask.

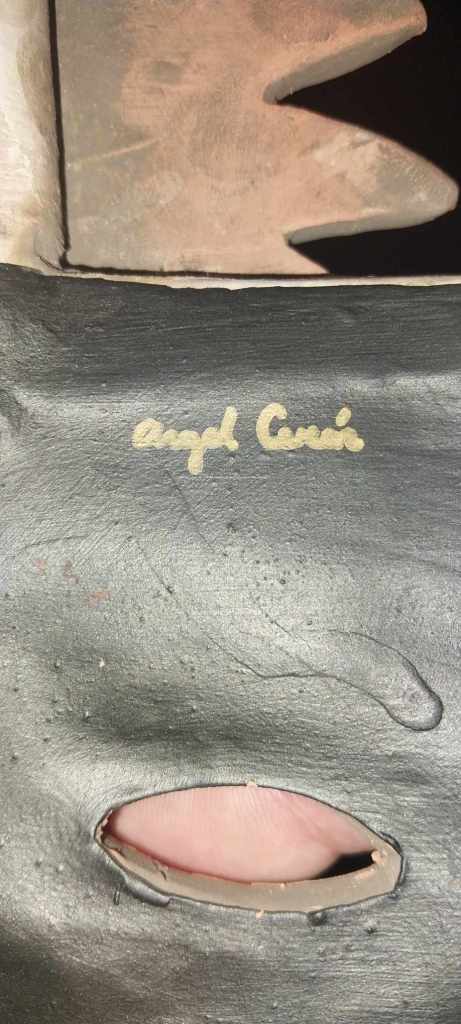

The next couple of masks I sourced circa Dia de Muertos 2024. Another Facebook Marketplace find that only cost me $30 for the pair. The timing of the find is somewhat poignant as the mask maker, Angel Cerón, se petateó (1) at the age of 69, in 2022.

- was wrapped in his petate. See FOMEX and Dia de Muertos 2024

Angel comes from a family with generations of artisan experience. He learned the family ceramic techniques from his father, Antonio Cerón Orta, a renowned artisan. Angel began a long study of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic cultures and learned the Nahuatl language spoken in ancient Mesoamerica.

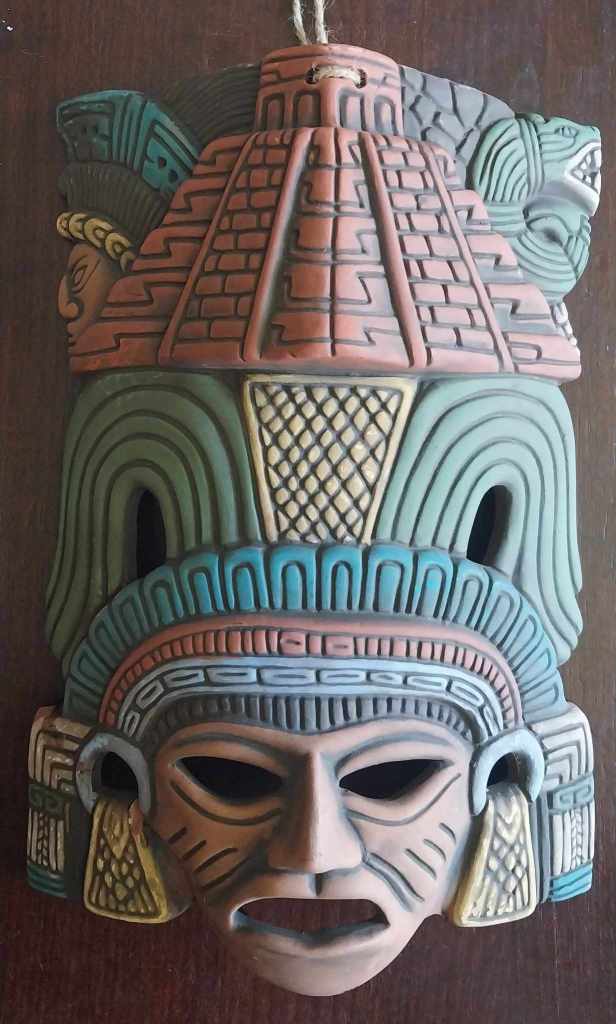

The masks now in my collection consist of……

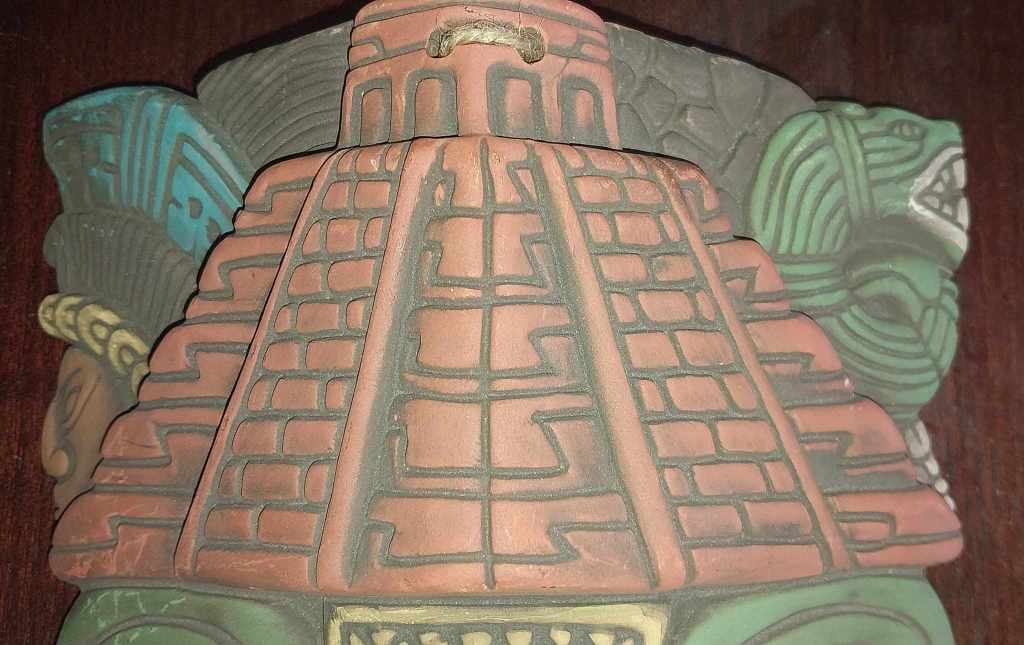

…..a ceramic mask depicting the fierce face of a Mayan with ornate jewellery and quetzal feather headdress. Above him is the image of El Castillo, the main pyramid in Chichen Itza and Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent of pre-Hispanic legend.

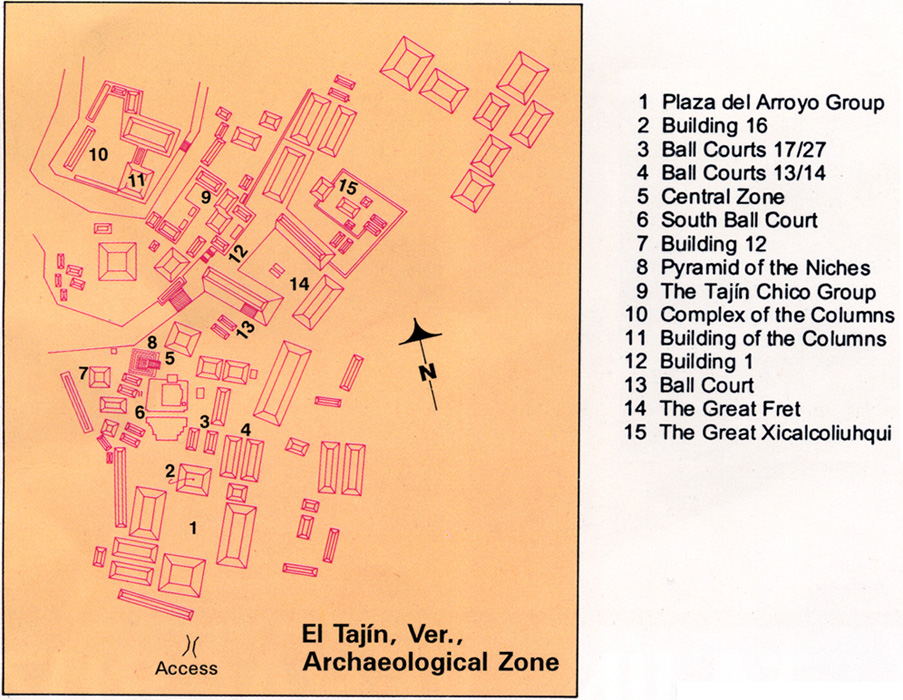

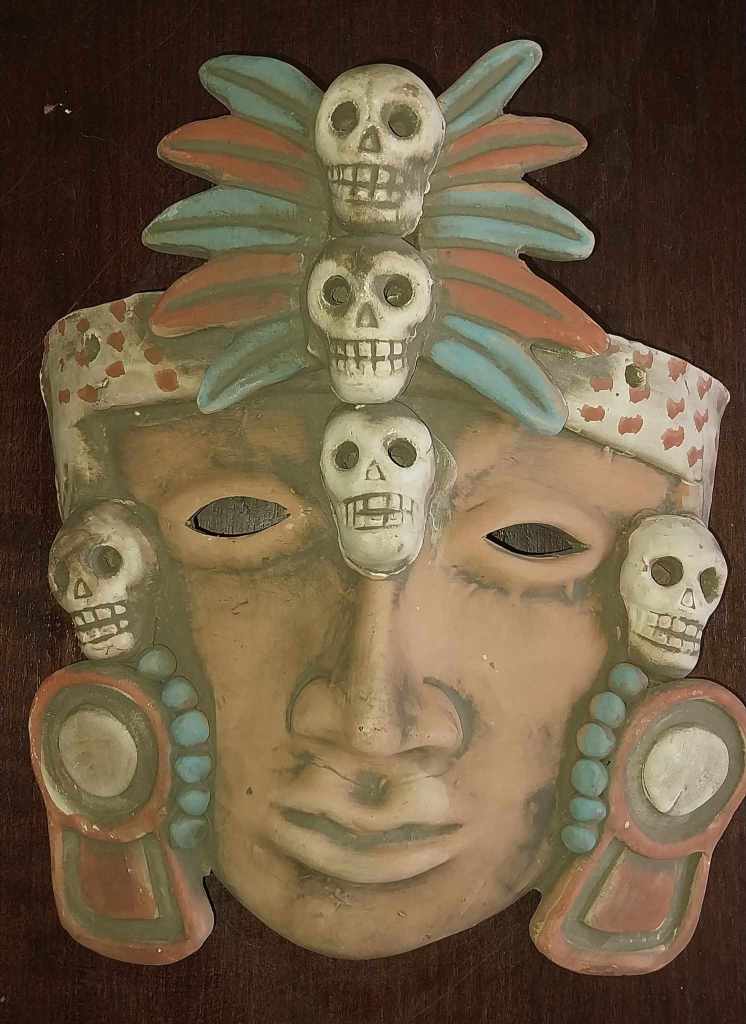

The next mask depicts skulls crowning the face of a “Pelotero del Tajín” or ball player from Mexico’s Totonaca culture that flourished in what is now Veracruz.

The archaeological site at El Tajin boasts some 17 ball courts.

The headdress pays tribute to the pre-Hispanic god of death.

Unfortunately the headdress on my mask has been damaged. It appears that the crest of feathers on the top has snapped off at some stage.

The master artisans with whom Angel worked continue his work, upholding his legacy as the Angel Ceron Artisan Association. The Association is composed of Milton González, Emilio Espejel, Brian Gonzalez, Isaac Espejel, Adrian Gonzalez, Josefina Claudio, Jorge Esparza, Saul Landon, Mauricio Hernandez, Guadalupe Lopez, Magdalena Torres, and Erick Contreras. Each artist is charged with a type of sculpture and specializes in a particular technique.

The process of creating these works is truly an art

First the proper materials must be acquired. Ceróns artisans use clay from northern Oaxaca state, the only clay of this kind in Mexico and perhaps in the world. The unique characteristics of this yellow clay make it ideal for moulding. It dries evenly and is especially hard, thus it is resistant to impact and can withstand very high temperatures.

The clay is ground in a mill, deposited in tubs of water and stirred constantly until it acquires a homogeneous consistency. This step can take hours. Left to stand for three days, it remains a thick liquid. It is then strained and rested for one more day

During the winter this is hard work, performed in the open air.

The blocks of clay are divided into smaller portions and dried in the sun for several hours. Only a qualified artisan can determine when the clay has reached the proper consistency. Then it is kneaded by hand, much as one kneads bread dough, and again it takes a skilled artisan to determine when it is ready to be worked.

Maestro Cerón then began the process of shaping his sculptures, some of them much more complex than others. The details are created totally by hand and some figures are so complicated that they are absolutely unique or part of limited editions.

Each piece is modelled by hand and the artisan’s talent is a crucial factor.

Once shaped, the sculptures dry as long as needed, some for as long as a week. They must dry in the shade because the clay might split and crack in the sun. Once dry, they are adorned with mineral pigments and high-fired at temperatures of up to 2,327º F for eight to twelve hours, depending on the season (the kilns are located outdoors). After firing, the pieces need to stand for six hours allowing them to gradually cool down.

Finally, they receive a bath of earth to give them their unique antique effect, which features slight cracks.

These are some beautiful additions to my collection.

References

- Angel Ceron Artisan Association (via the Smithsonian Institution) – https://festival-marketplace.si.edu/angel-ceron-artisan-association-r7-a4012/

- Beidler, A., & Andrews, J.R. (1975). Introduction to Classical Nahuatl.

- Cowgill GL. (2015) Ancient Teotihuacan: Early Urbanism in Central Mexico. Cambridge University Press.

- Furst, Peter T. (1995), “Shamanism, Transformation, and Olmec Art”, in Coe, Michael D., et al, The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership, Princeton, The Art Museum, Princeton University, pp. 68-81

- Jiménez, Maya. Dr (2024) Teotihuacan : https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-americas/early-cultures/teotihuacan/a/teotihuacan

- Milton, George and Gonzalo, Roberto. “Jaguar Cult — Down’s Syndrome — Were-Jaguar.” Expedition Magazine 16, no. 4 (July, 1974): -. Accessed October 08, 2024. https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/jaguar-cult-downs-syndrome-were-jaguar/

- Murdy, C. N. (1981). Congenital Deformities and the Olmec Were-Jaguar Motif. American Antiquity, 46(4), 861–871. https://doi.org/10.2307/280112

- Slater, F., (2010) “Were-jaguars and jaguar babies in Olmec religion”, Essex Student Journal 3(2). doi: https://doi.org/10.5526/esj114

- Snow, Dean R.; Gonlin, Nancy; and Siegel, Peter E., (2020) +”The Archaeology of Native North America”.

- Stirling, Matthew W. (1968). Elizabeth P. Benson (ed.). Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec, October 28th and 29th, 1967. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. pp. 1–8. OCLC 52523439. Archived from the original (PDF online reproduction) on 2006-08-22.

Images

- Amuzgo region tigre – https://mexicandancemasks.com/?p=1308

- Danza de los Tecuanes – https://cronicapuebla.com/cultura/charro-de-los-tecuanes

- Danza de los Tigres de Zitlala – https://www.infobae.com/america/agencias/2021/05/06/pelea-de-tigres-un-ritual-al-dios-de-la-lluvia-que-se-mantiene-en-mexico/

- Danza del Tigre y los Tlaminques – https://www.facebook.com/DanzaDeLosTlaminques/photos/pb.100066461151605.-2207520000/135350707865694/?type=3

- Danza de los Tlacololeros – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=10165856800190333&set=a.467956905332

- La Ciudadela Mercado de Artesanias in Mexico City – https://www.facebook.com/MERCADODEARTESANIASLACIUDADELA

- Mask vendor at Palenque – https://gigazine.net/gsc_news/en/20130514-mexico-palenque/

- Olmec Jade Mask. 900-400 B.C. Mexico. Vault of the metropolitan museum of art – https://www.reddit.com/r/ArtefactPorn/comments/134a5xi/olmec_jade_mask_900400_bc_mexico_vault_of_the/#lightbox

- Olmec jade mask – Giovanni Testori (1923-1993) collection – https://bertolamifineart.bidinside.com/en/lot/54965/a-green-jade-mask-olmec-style-167-cm-high-/#gallery-1

- Olmec map – https://worldinmaps.com/history/olmecs/

- Olmec stone head – https://www.reddit.com/r/Damnthatsinteresting/comments/14kqo92/a_colossal_stone_head_from_the_olmec_civilization/#lightbox

- Olmec were jaguar – 900 to 600 BC – https://www.bidsquare.com/online-auctions/artemis-gallery/stunning-olmec-jade-maskette-were-jaguar-transforming-2432372#mz-expanded-view-352779687926

- Remojadas Culture Area map – By Madman2001 – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18422641

- Similar masks for sale in Puerto Vallarta – https://www.ellgeebe.com/en/destinations/latin-america/mexico/puerto-vallarta/things-to-do/pueblo-viejo-mercado-de-artesanias

- Sonrientes figure and mask – By frida27ponce – Flickr (https://www.flickr.com/photos/frida27/320429463/in/photostream/), CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1732363

- Tigre mask Chilapa – https://mexicandancemasks.com/?p=1204

- Were Jaguar axes (1)(2)(3) – https://www.latinamericanstudies.org/werejaguar-axes.htm

- Were Jaguar mask (1) – https://www.latinamericanstudies.org/olmec/werejaguar-maskette-3.gif

- Were Jaguar mask (2) – https://i.pinimg.com/originals/dd/41/11/dd411126ebf4040fced5b5cbfcb1b685.jpg

- Were Jaguar mask (3) – https://i.pinimg.com/originals/c5/9a/ce/c59acedcd88f75b3cb83122f09f65636.jpg

- Yaqui Deer Dancer (Danza del Venado participant) – https://es.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archivo:Danza_del_venado_yaqui.jpg

- Zitlalan tigre mask – https://en.carlafernandez.com/collections/folk-art