The investigation into this quelite came about as a result of one of my favourite anise scented herbs, Pericón (Tagetes lucida) (1) which also just happens to be in one of my favourite genera (and Families too now that I think on it – family Asteraceae in case you wondered). Sorry, got side-tracked, it happens on occasion. Now, pericón is also colloquially known as “cloud” herb or “grass of the clouds”. I have pondered why this is so and there are several possibilities. The first was geographical and involved its habitat being in mountainous regions, “among the clouds” or in environmental regions known as “cloud forests” (2). The herb was consecrated to Tlaloc and was used as an incense to him (clouds of wafting smoke perhaps?). It was also said to be used in sacrificial ceremonies where it would be powdered and thrown into the eyes of those about to be sacrificed so as to calm them and make them more amenable to the process (a clouding of consciousness perhaps?)

- Quelite : Pericón : Tagetes lucida

- A cloud forest, also called a water forest, primas forest, or tropical montane cloud forest, is a generally tropical or subtropical (in a latitude typically from 25°N to 25°S), evergreen, montane (from 500 m to 4000 m above sea level), moist forest characterized by a persistent, frequent or seasonal low-level cloud cover, usually at the canopy level

Tagetes lucida

Tzitziqui. A Tagetes?

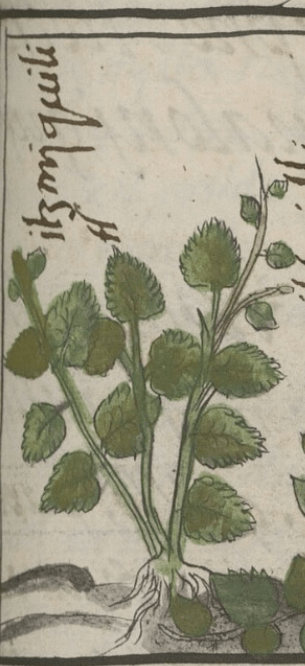

They call the yauhtli the cloudy plant, because it has flowers shaped like heads of hair, which sometimes look like clouds, or because it removes clouds from the eyes. The Mexicans are accustomed to call it tzitziqui [Tagetes lucida] (Healey 2024)

During Dia de Muertos the use of plant offerings (especially the offering of cempoalxóchitl flowers (Tagetes spp.) known as “cempasuchil) in the altars (ofrendas) of the home or on the graves in the cemetery are one of the major symbolic elements of this fiesta. Serrato-Cruz (2022) notes that “Prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, the Nahuatl-speaking indigenous people recognized that the cempoalxóchitl plant comprised several species, known as female and male cempoalxóchitl” (Tagetes erecta L., which has the largest flower and is the most commonly used bloom). Amongst the other species of cempoalxóchitl being used prehispanically Serrato-Cruz notes “macuilxóchitl (T. lunulata Ort .), tepecempoalxóchitl (T. patula L.), oquichtli, tlapalcozatli, tlapaltecacayac, tzitziquilitl, yiahutli (T. lucida) and zacaxochitlcoztic”. Here he places tzitziquilitl in the Tagetes family but does not indicate a specific species (as he does with some of the others). It was also noted that “this range of species was linked to the solar star due to its shape and color” (Vázquez et al., 2002; Serrato, 2014), and that “a reminiscence of that past is found in the word tonalxóchitl (flowers of the sun), which is the name given to some cempoalxóchitl species that grow in the countryside in Malinalco, State of Mexico”, (Vázquez et al., 2002).

Lets have a look at another name on the list, Zacaxochitlcoztic (Vázquez et al., 2002).

- Zacatl – grasses, hay, straw, weeds

- Zacate – borrowed from Mexican Spanish, borrowed from Nahuatl zacatl “dry grass, hay,” going back to Uto-Aztecan *saka-t (whence also Tarahumara sakará “grass for forage,” Southern Tepehuan va-haak “grass stems,” Hopi tuusaqa “grass”

- Xochitl – flower

- Coztic – yellow

So we have a grassy herb/plant (grass like foliage?) plant with yellow flowers. I see a theme developing.

cloud plant (planta nublossa)

They call it yauhtli or cloudy plant because it has flowers in the form of a stem that in a certain way looks cloudy or because it dissolves and removes the clouds from the eyes, the Mexicans usually call it tzitziqui, which has willow-like leaves serrated with elbow stems, which grow from a thin root, the flowers are slow and composed in the manner of a hat, the smell and work are no different, it is like anise, as well as the taste, as in everything else, sharp and somewhat bitter, it is desired in temperate places, such as the fields of Mexico, and I have also seen it in warmer places, although it usually grows in the mountains, it flowers in the time of the rains until September, which is the time that corresponds to our summer in Spain, the seed is collected in November, and the leaves and stems in February, but the root must be collected in December and if it is taken to Spain as far as I can reach with my conjecture it would be very good in the land of Madrid and would even be of great ornament and beauty to the gardens of the King, it is hot and dry, almost in the 4th degree, and that any part of this plant or each one or all together in any way that they apply it to the body, and it is seen from it that urine and menstruation are produced, it expels the dead creature from the belly, it is useful for coughs and expels flatulence, it comforts the stomach when it is loose, it corrects the bad smell of the mouth and engenders milk, it is contrary to poisons, it mitigates the pain of the throat, it is useful for the insane, and for those who were stunned and frightened by lightning, it staunches the flow of blood, it quenches the thirst of those with iodine, and the cold of fevers, applying it alone or using it in incense, They also say that mixed with viper’s juice and given to drink, it repairs broken veins, the vapor of the decoction is very useful for swollen noses, and minced green and put in the form of a poultice on bad ears they usually heal and placed in the same way on swellings, and on abscesses, it dissipates them and resolves, heats the stomach and cures nausea, especially in children, cleans the kidneys and bladder of sand and boils and of the thick and tenacious phlegm, which tends to clog those passages, thins the humors, and placed with honey on the stomach pit it stops vomiting, generates matter, heals wounds, is useful to the mother, and drives away bedbugs, heals xaqueca (migraine headaches), which is considered one of the benefits of this plant, and taking for nine consecutive days on an empty stomach the water in which it has been in infusion, it heals with admirable effect the enpeynes (ringworm?) and, in short, it is a kind of ypericon not known in our Spain

(Hernández 1888).

Same book (Hernández 1888) but different edition. And from the Library of John Carter Brown no less (This guy and his books have come up before…. …I’ll have to put some research time into him I guess

Lets see what others have to say of the plant.

Manuel Urbina (1903) notes

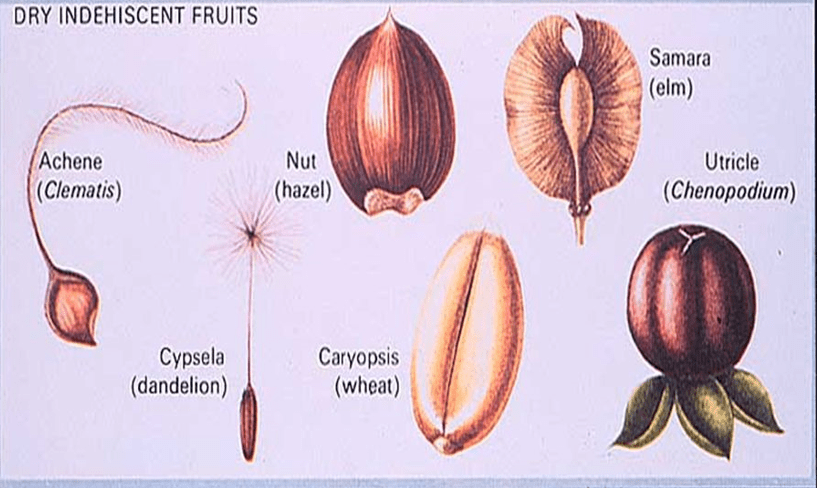

“There are some Mexican words: Tzitziqui, Pipitza and Eloquilitl, which are capable of an interpretation, perhaps a risky one, but whose foundation could be rectified later. Remi Simeon brings the meaning of Tzitziquiloa: p. otzitziquilo: nite., to sacrifice, to cut its flesh. This interpretation can be applied to the plants that the Indians call Tzitziqui as a generic term and that belong to the Compositae family. In effect: the fruits of these species are cypselas (1) or achenes that have pappus or tufts made of bristles, rigid straws and sometimes thorns that can easily hurt, injure the hands when they are collected or when one inadvertently passes near them. In this way I understand why our natives gave the name Tzitziquilitl or Tzitziqui to the species of this family that they used as food, without ignoring that it also expresses the very green color of certain quelites: the word Tzitzicaztli refers not only to the wound but to the stinging that it produces, as happens with nettles.”

- cypsela noun, plural cypselae : a one-seeded, indehiscent (2) , dry fruit formed from an inferior ovary and with a fused calyx, characteristic of the Asteraceae

- indehiscent : adjective : Botany : (of a pod or fruit) not splitting open to release the seeds when ripe : remaining closed at maturity. They are dry fruits that open up only upon deterioration or spread by consumption by animals.

Note the cypsela in the image above (the dandelion).

It bears resemblance to both the Bidens and the Porophyllum seeds as shown below.

I only show the Porophyllum linaria (Pipitza) seed above because of its relation (both botanically and etymologically) to Tzitziqui and Eloquilitl.

Urbina (1903) mentions above the meaning of “Tzitziquiloa: p. otzitziquilo: nite., to sacrifice, to cut its flesh”.

Which is interesting as another quelite involving “cutting of the flesh” (linguistically speaking) is “itzmiquelite” or Obsidian arrow quelite : Portulaca oleracea : Verdolagas. itztli : Principal English Translation : a sharp-bladed instrument of obsidian which relates to Itzmītl : Flèche à pointe d’obsidienne : Obsidian tipped arrow and is added to quilitl : Principal English Translation : edible herbs and vegetables

Etymology

- tzitziquiloa : Principal English Translation: to lance someone

- Tzitziquiloa : to scarify someone, to incise their flesh. / vt tla-., to make cuts.

- tzitziquiltic: (Schwaller) scarified; serrated; jagged. This last one is interesting as in the image below (left) Sahaguns work depicts tzitziquilitl as having a serrated/jagged leaf margin. Purslane (Verdolagas) does not have a leaf margin life this. The “leaves” are small, smooth and (in some cases) quite succulent.

Another interesting point made by Urbina was “the word Tzitzicaztli refers not only to the wound but to the stinging that it produces, as happens with nettles.” which, when we look at Sahaguns Itzmiquilitl we see a correlation. Sahaguns itzmiquilitl looks to me (an untrained botanist but a very well trained herbalist) to be the very image of a stinging nettle (Urtica dioica)

For more information on itzmiquilitl check out Quelite : Verdolagas : Purslane and Ixmiquilpan : Land of the Obsidian Arrow Quelite

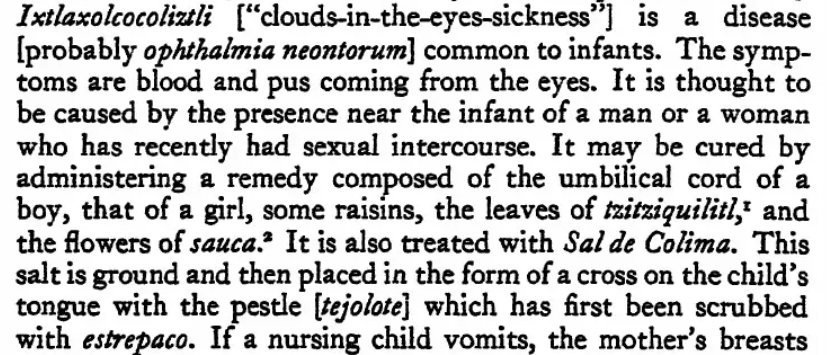

Tzitziqui comes up in the Codex as an Aztec name for a Tarascan (Purépecha) medicinal plant (1) called Huitzo’cuilcuitlapil-patli. This is the only specific mention of the plant in the Codex.

- the suffix -patli (-pahtli) signifies the plant as having a medicinal use.

Tzitzi comes up again a few times as part of their botanical nomenclature.

- Tzitziquil “split” – refers to serrate leaf margins. This is not really relevant to T.lucida but if we look at the Bidens species the description is on the mark.

- Tzitzin “small” – referring to the size of the plant. In this case for the town Ahua-tzitzin-co, among the small oaks. (Ahuatl “live oak” : tzitzintli – emphatic of diminutive particle : co “place of”) Referring to Quercus parva (the Dwarf Oak); only part of the main trunk is shown, to denote the tzitzin, ‘ small,’ and this is reinforced by the regular glyph for something half-sized, the lower half of a human body.

So, going by this nomenclature, tzitziqui(litl) translates to “small quelite”? I somehow doubt it but hey, I’m kinda new to Nahuatl. Or does it refer to serrated leaf margins? We’ve already looked at the “cutting” re tzitziquiloa as noted above which refers to the plants ability to “cut” via its sharp seeds (as well as the “wound” caused), “the word Tzitzicaztli refers not only to the wound but to the stinging that it produces, as happens with nettles.” (Urbina 1903)

Other plants noted as being tzitziquilitl

We stay within the quelite classification but we now wander from the Tagetes species looking to identify tzitziqui(litl).

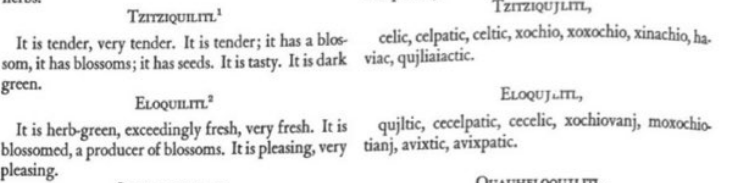

Salazar (2003) and the Digital Library of Traditional Mexican Medicine. National Autonomous University of Mexico (2009) note of a herb in the Bidens family called Aceitilla (Bidens pilosa) which has the Common Names of Eloquilitl and Zitziquilitl (1) that it is used in “traditional medicine for gastritis, kidney pain, cough, diarrhea, and to lower blood pressure. And for vitamin tonics. The plant contains iron, potassium, calcium and magnesium.“

- in the excerpt of the General History of the Things of New Spain, Book 11, Earthly Things as shown previously Eloquilitl is also identified as being Bidens pilosa.

Tzitziquilitl : Redfield (1930) notes this as being Bidens leucantha (1).

- which according to most botanical references is a synonym for Bidens pilosa. One source (Kew Royal Botanical Gardens) noted it as being a synonym for Bidens alba.

I have looked at the Bidens species in a previous Post : Aceitilla : Bidens pilosa. The Post goes into detail on the culinary and medicinal uses of herbs in this family. It should also be noted that herbally speaking the two plants (alba and pilosa) can be used interchangeably. This is often the case with closely related plants.

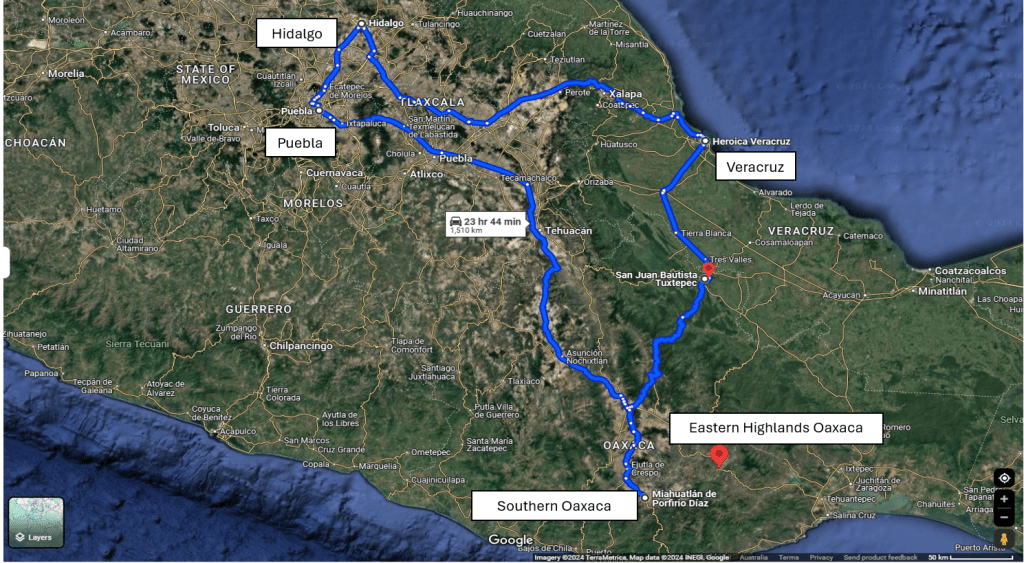

This herb (Bidens pilosa) is used (under the name mozote) by Mixes (1), Totonacas (2) and Zapotecos (3) for the treatment (para curar) of susto (4).

- The Mixe (Spanish mixe or rarely mije [ˈmixe]) are an Indigenous people of Mexico who live in the eastern highlands of the state of Oaxaca.

- The Totonac are an indigenous people of Mexico who reside in the states of Veracruz, Puebla, and Hidalgo

- The Zapotecs are an indigenous people of Mexico . The Zapotec population is concentrated mainly in the southern state of Oaxaca and its neighboring states.

- See Posts What is Curanderismo? and Glossary of Terms used in Herbal Medicine. for more information on this condition.

It has a fairly wide range of use. The map above is of the main areas listed where it is utilised medicinally by indigenous peoples. CONABIO (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad) widens its range a little.

Its distribution in Mexico “has been recorded in Aguascalientes, Baja California Norte, Baja California Sur, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Colima, the Federal District, Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Jalisco and the State of Mexico. In addition, it is found in Michoacan, Morelos, Nayarit, Nuevo Leon, Oaxaca, Puebla, Queretaro, San Luis Potosi, Sinaloa, Sonora, Tabasco, Tlaxcala, Veracruz and Zacatecas,”

The Monografía de Plantas Medicinales en Michoacán (Monograph of Medicinal Plants in Michoacán) is a little more precise and lists regions where it is recorder to be used medicinally.

It is located in the towns of Apatzingan, Ario de Rosales, Carácuaro, Charo, Chilchota, Coalcoman, Coeneo, Erongaricuaro, Huaniqueo, Indaparapeo, Jiquilpan, Los Reyes, Morelia, Ocampo, Paracho, Patzcuaro, Puruandiro and Quiroga. In addition to Salvador Escalante, San Lucas, Tancítaro, Tangancícuaro, Tarímbaro, Tzintzuntzan, Uruapan, Jiménez, Zamora, Zinapécuaro and Zitácuaro, in Michoacán.

This is just to say that it seems to be a fairly widely used plant.

Under the indigenous common names of Bidens pilosa as listed in my research I found the following

Náhuatl – tzitziquil, chichiquelite (1), tzitziquilistac, iztacmozot

Estado de Mexico – tzitzi quil, tzitziquilistacayana

Puebla – iztacmozot (Nahua), ñadoni (Otomi)

- Further north (Sonora and into SW USA) chichiquelite refers to the huckleberry (a nightshade berry in the Solanum species). In some texts chichiquelite is listed as Bidens odorata.

Tzitziquilitl is also poetically immortalised in a prehispanic prayer to Tlaloc (1). This is interesting as the very first quelite we looked at, pericón, is dedicated specifically to Tlaloc and used in treatments (or as a protective amulet) against illnesses and conditions associated to the realm of Tlaloc. Pericón could be used as a protective amulet to protect from drowning when crossing rivers or from being hit by lightning (2). Medicinally it is used to treat conditions associated with Tlaloc such as dropsy, leprosy, scabies, gout, aches and pains, people with stunted growth, and the physically disabled.

- who is called “Lord of the Sweet-Scented Marigold” – which is identified as Yauhtli (Tagetes lucida)

- crosses made from pericón are also hung in crops (again to protect from storm damage/lightning strike) and above the doorways of homes to protect them from el chamuco (the devil). Read Quelite : Pericón : Tagetes lucida for more on this custom.

So these herbs are all related to Tlaloc in some way. I would wager to say they’re all medicinal (although I am not overly familiar with two of them). The translation does note that they are at the very least “all edible”.

The prayer (or at least the translators of it) identify tzitziquilitl as being a different plant again, Erigeron pusillus,

(Extract from) A Prayer to Tlaloc – Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl

ca ye ixquich tlaihiyouia in yoyolitzin,

in zaquan, in quechol: ca za tlamauilani,

za netzitzineualo, za metzonicquetzalo,

oconomotoptemilito, oconmopetlaealtemilito

in imitzmolinea in incelica:

in ayauh tonan, in tzitziquilitl, in itzmiqluilitl, in tepicquilitl (1)

in ixiquich in celic, itzmolinqui,

in itzmolini, in celiani,

in xotlani, in cueponini,

- Ayauh tonan: Cuphea jorulleusis HB1; tzitziquilitl: Erigeron pusillus Nutt.; ltzmiquilitl: Portulaca rubra (?); tepicquilitl: Mesembryan-themum blandum L. All are edible plants. A Prayer to Tlaloc – Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl

Oh, the sustenances of life are no more, they have vanished;

the gods. the Provider, have carried them off,

they have hidden them away in Tlalocan;

they have sealed in a coffer, they have Iocked in a box,

their verdure and freshness

the cuphea and fleabane, the purslane and fig-marigold

all that grows and puts forth,

all that bears and yields,

all that sprouts and bursts into bloom.

all vegetation that issues from you

and is your flesh, your germinatíon and renéwal.

The extract above starts from (about the middle) of page two of the poem (see middle image below – p44) and continues onto the third page.

Translations of A Prayer to Tlaloc

Tzitziqui is also mentioned in a Tarascan poem

Cuidado, cuidado,

con la flor de añil,

no te envuelva

y quiera florecer

y la flor blanca se vaya a enojar

y la flor amarilla se vaya a marchitar.

Cuidado, cuidado,

con la flor de añil*.

Be careful, be careful

with the indigo flower,

don’t let it envelop you

and try to bloom

and the white flower get angry

and the yellow flower wither.

Be careful, be careful

with the indigo* flower.

*flor de añil translates directly into “indigo flower” but CONABIO (Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad) mentions hierba añil (where la flor de añil comes from) and identify it as Tagetes lucida.

This was a snippet of a poem I found in a Spanish Language textbook. I wish I had some more context for the poem. It appears to be part of a warning about how to treat the plant with regards to its harvesting.

Indigo.

- a tropical plant of the pea family, which was formerly widely cultivated as a source of dark blue dye.

2.

a colour between blue and violet in the spectrum

Other flowers noted as being “indigo” (and I guess in this case it has more to do with blue colouration) although some are related to our indigo as shown above.

It is safe to say that the “flor de añil” we are looking at is not an Indigofera species.

Lets look at one of the plants noted in the Prayer to Tlaloc.

Erigeron pusillus

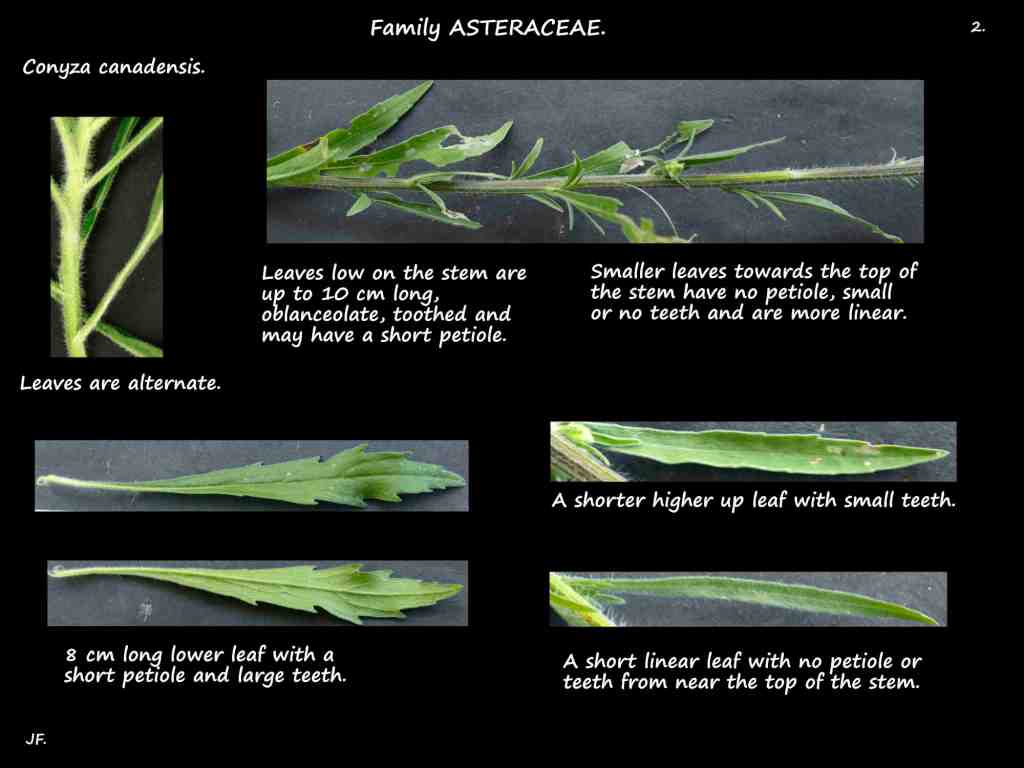

Conyza canadensis

Fleabane is a Common Name for this plant.

Erigeron pusillus is a synonym of Erigeron canadensis, which is a synonym of Conyza canadensis. CONABIO (the Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad) notes in a publication on Bosque Mesófilo de Montaña de México (Mexican Mesophilous Mountain Forest) identifies tzitziquilitl as being Conyza canadensis var. glabrata.

The young leaves were often used as a flavouring substitute for tarragon and many people say that the taste is similar (much like pericón). The young plants were also boiled and used as a potherb in soups and stews.

The leaves are best dried and stored for later use.

The young seedlings are also edible. Native people once pulverized the young tops and leaves and ate them raw (similar to using an onion).

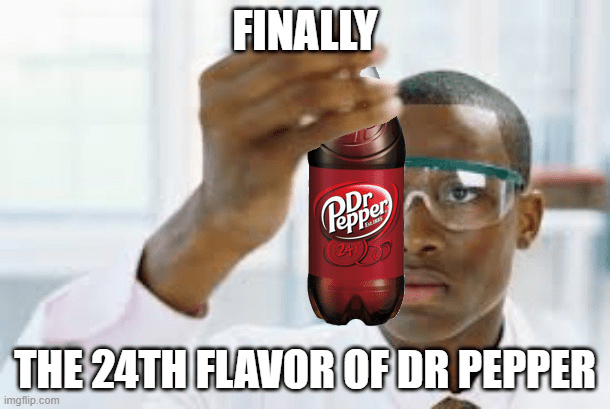

The plant is the source of an essential oil that is used commercially for flavouring sweets, condiments and soft drinks (Facciola 1990); and Samuel Thayer (2017) suspects it is the mystery flavour in Dr. Pepper.

Conyza canadensis can easily be confused with Conyza sumatrensis and Conyza bonariensis. Conyza canadensis is distinguished by hairless or nearly hairless bracts which lack a red dot at the top but have a brownish inner surface. Conyza sumatrensis has hairy bracts but there are no long hairs near the top of the bracts. Also inner surface of bracts are reddish brown. Conyza bonariensis has densely hairy bracts, and is especially hairy on the stems and around the leaf axils.

In traditional North American herbal medicine, Canada fleabane was boiled to make steam for sweat lodges, taken as a snuff to stimulate sneezing during the course of a cold and burned to create a smoke that warded off insects.

It can be harvested at any time that it is in flower and is best used when fresh

The whole plant is antirheumatic, astringent, balsamic, diuretic, emmenagogue, styptic, tonic and vermifuge.

Pharmacological studies show that Erigeron canadensis exerts antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticoagulant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, mutagenic, gastric protective effects and skin depigmentation activities (Al-Snafi 2017).

The plant was used for the treatment of wounds, swellings, and pain caused by arthritis in Chinese folk medicine (Li 2002).

Zuni people insert the crushed flower of Conyza canadensis variety into the nostrils to relieve sneezing and rhinitis (1) (Chevallier 1996). The leaves of Erigeron canadensis were prepared as tonic to be used in the treatment of diarrhoea, diabetes and haemorrhages (Sharma etal 2014). An infusion of the plant has been used to treat diarrhoea and internal haemorrhages or applied externally to treat gonorrhoea and bleeding piles (Weiner 1983)

- Irritation and swelling of the mucous membrane in the nose. Most common types include the common cold (A viral infection of the nose and throat) and seasonal allergies (allergic responses causing itchy, watery eyes, sneezing and other similar symptoms)

The plant was used in folk medicines in the northern areas of Pakistan for the treatment of various pathological conditions including acute pain, inflammation, fever and microbial infections including urinary infections, respiratory tract infections, diarrhoea and dysentery (Shakirullah etal 2011).

In Korea, the plant was used to treat allergic diarrhoea, stomatitis (1), otitis media (2), conjunctivitis, and acute toothache (Park etal 2013) The plant was also used as an anthelmintic (3), a mild hemostyptic (4), for uterine bleeding, gout, rheumatic symptoms, dropsy (5), tumours, and bronchitis.

- A condition that causes painful swelling and sores inside the mouth

- An infection of the air-filled space behind the eardrum (the middle ear).

- A medicine used to treat infections caused by a broad range of parasites

- Something that stops the flow of blood from a small wound

- refers to fluid accumulation/swelling under the skin and is generally known today as ‘oedema’ or ‘edema’.

In African folk medicine, it was used in the treatment of granuloma annulare (1), sore throats, urinary tract infections and for medicinal baths. In homeopathic medicine, Erigeron canadensis was used for bleeding of the bladder, haemorrhoids, menorrhagia (2) and metrorrhagia (3), gastritis (4), hepatitis (5) and cholecystitis (6).

- a skin condition that causes a rash of raised bumps in a ring shape. It’s usually harmless and not contagious. The most common type affects young adults, usually on the hands and feet

- heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding

- also known as intermenstrual bleeding, is vaginal bleeding that occurs outside of a menstrual period. It can be light or heavy, and may be associated with pain or cramps

- a redness and swelling (inflammation) of the stomach lining. It can be caused by drinking too much alcohol, certain medicines, or smoking. Some diseases and other health issues can also cause gastritis

- a general term for liver inflammation that can be caused by viruses, chemicals, drugs, alcohol, or genetic disorders

- Inflammation of the gallbladder, a small digestive organ beneath the liver. Cholecystitis is often caused by stones that block the tube leading from the gallbladder to the small intestine. Severe pain in the upper-right belly and bloating are symptoms. Treatment includes a hospital stay and surgical removal.

A tea of the boiled roots is used to treat menstrual irregularities

An infusion of the plant has been used to treat diarrhoea and internal haemorrhages or applied externally to treat gonorrhoea and bleeding piles

The essential oil found in the leaves is used in the treatment of diarrhoea, dysentery and internal haemorrhages

Dried plants were scattered in animal bedding to prevent fleas.

**WARNING** This plant is a uterine stimulant so should not be used by women who are pregnant (or trying to become pregnant)

Another writer (Jaime Ramos Méndez) speaks of a variety of Dahlia is called “Zaluantzitziki” in Purépecha where tzitziqui signifies flower in that language.

At this point I’m going to have to go with Bidens pilosa as tzitziqui.

Oh, for an Aztec botanist.

References

- Al-Snafi, Ali. (2017). PHARMACOLOGICAL AND THERAPEUTIC IMPORTANCE OF ERIGERON CANADENSIS (SYN: CONYZA CANADENSIS). Indo Am J P Sci. 4. 248-256. 10.5281/zenodo.344930.

- Castro RAE. 1994. Origen, naturaleza y usos del cempoalxóchitl. Revista Geografía Agrícola 20: 179-189.

- Chevallier A. Encyclopedia of herbal medicine. DK Publications 1996: 276.

- Cruz, Martín de la, Juan Badiano, Emily W. Emmart Trueblood, Biblioteca apostolica vaticana Barb Lat 241, and Katherine Golden Bitting Collection on Gastronomy (Library of Congress). 1940. The Badianus Manuscript, Codex Barberini, Latin 241, Vatican Library : An Aztec Herbal of 1552. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Elferink, J. G. R. & Flores Farfán, J. A. (post 2015) Yauhtli and Cempoalxochitl: The sacred marigolds. Tagetes species in Aztec medicine and religion, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropologia Social (CIESAS)

- Facciola. S. Cornucopia – A Source Book of Edible Plants. Kampong Publications 1990 ISBN 0-9628087-0-9

- Gates, William (2012) An Aztec Herbal: The Classic Codex of 1552 (A translation of the Codex Cruz-Badianus Aztec Herbal of 1552) Publisher: Courier Corporation, ISBN 0486140970, 9780486140971

- Healey, Kevin (2024) Pericón: A Culinary Marigold that Will Not Get You High : The Ethnobotany of Foraged Food & Peculiar Produce : https://www.pullupyourplants.com/archive/pericon

- Hernández, F., Ximénez, F. (1888). Quatros libros de la naturaleza y virtudes medicinales de las plantas y animales de la Nueva España.

- Hernández, Franciso (1959). Historia natural de la Nueva España. 2 vols. Mexico: Editorial Pedro Robledo Ortiz de Montellano, Bernardo

- Hernández, Franciso (1980). “Las hierbas de Tlaloc.” Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 14: 287–314.

- Hernández, Franciso (1990) . Aztec Medicine, Health, and Nutrition. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Li TSC. Chinese and related North American herbs- Phytopharmacology and therapeutic values. New York, USA, CRC Press 2002.

- Park WS, Bae JY, Chun MS, Chung HJ, Han SY and Ahn MJ. Suppression of gastric ulcer in mice by administration of Erigeron canadensis extract. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2013; 72: (OCE4), E263 doi:10.1017/S0029665113002887

- Picó, Belén; Nuez, Fernando. Minor crops of Mesoamerica in early sources (II). Herbs used as condiments Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution; Dordrecht Vol. 47, Iss. 5, (Oct 2000): 541-552. DOI:10.1023/A:1008732626892

- Redfield, Robert (1930) Tepoztlan, a Mexican village; a study of folk life : The University of Chicago Press, 1930

- Redfield, Robert. (1928) “Remedial Plants of Tepoztlan: A Mexican Folk Herbal.” Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 18, no. 8 (1928): 216–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24522654.

- Salazar, G.L. 2003. Ethnobotanical Garden Collection Catalog. INAH, Morelos

- Serrato CMA. 2014. El Recurso Genético Cempoalxóchitl (Tagetes spp.) de México (diagnóstico). Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UACH)- SINAREFI-SNICS-SAGARPA. 182 p

- Serrato-Cruz MÁ. 2022. Cultivation methods and cultural motives for growing “flor de muerto” (Tagetes erecta L.). Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo https://doi.org/10.22231/asyd. v19i3.1339

- Shakirullah M, Ahmad H, Shah MR, Ahmad I, Ishaq M, Khan N, Badshah A and Khan I. Antimicrobial activities of conyzolide and conyzoflavone from Conyza canadensis. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry 2011; 26(4): 468–471.

- Sharma RK, Verma N, Jha KK, Singh NK and Kumar B. Phytochemistry, pharmacological activity, traditional and medicinal uses of Erigeron species: A review. International Journal of Advance Research and Innovation 2014; 2(2): 379-383.

- Thayer, Samuel. 2017. Incredible Wild Edibles: 36 Plants That Can Change Your Life. Bruce, WI, Forager’s Harvest Press.

- Urbina, Manuel. (1903). Plantas comestibles de los antiguos mexicanos. Anales Del Instituto Nacional De Antropología E Historia, 2(1), 503–591. Recuperado a partir de https://revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/anales/article/view/6609

- Vazquez-Garcia, L. M. 2002. Cempoalxóchitl (Tagetes spp.) Recursos Fitogenéticos Ornamentales de México. Servicio Nacional de Inspección y Certificación de Semillas (SNICS) y la Universidad Autonóma del Estado de México (UAEM). México. 88p.

- Vázquez GLM, IMG Viveros F, E Salomé C. 2002. Cempasúchil (Tagetes spp): recurso fitogenético ornamental de México. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Colección Ciencias Agropecuarias. Serie Agronomía.

- Weiner. M. A. Earth Medicine, Earth Food. Ballantine Books 1980 ISBN 0-449-90589-6

Websites

- B.pilosa : World Flora Online : https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000044260;jsessionid=BDC4ADEF75E154120A0D03CE9CB9BC85

- B.pilosa : Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations : https://www.fao.org/agriculture/crops/thematic-sitemap/theme/biodiversity/weeds/listweeds/bid-pil/en/

- B.pilosa : GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility) : https://www.gbif.org/species/5391845 : this site also notes B.pilosa as being named Acocotli quauhuahuacensis by Hernandez in 1898

- B.alba : Kew Royal Botanical Gardens : Plants of the World Online : https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:184711-1#synonyms

- Conyza canadensis (4 images) : https://www.botanybrisbane.com/plants/asteraceae/conyza/conyza-canadensis/

- Conyza canadensis var. glabrata (tzitziquilitl) : Bosque Mesófilo de Montaña de México : Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO) : http://ipttest.conabio.gob.mx/iptconabiotest/resource?r=SNIB-SI-BMM&v=1.2&request_locale=es

- Erigeron pusillus (Images) : https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/325496-Erigeron-canadensis-pusillus : http://www.namethatplant.net/plantdetail.shtml?plant=3093

- Erigeron pusillus : https://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000126068;jsessionid=AF01213F9FF74D19FD9A426638BC5947

- Itztli – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/itztliItzmītl – https://gdn.iib.unam.mx/diccionario/itzmitl/51438

- Jaime Ramos Méndez : https://jaimeramosmendez.blogspot.com/2011/08/flores-silvestres-de-tarecuato-dalia.html

- Mozote : Atlas de las Plantas de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana : http://www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/apmtm/termino.php?l=3&t=mozote

- Quilitl – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/quilitl

- Tzitziqui – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tzitziqui

- Tzitziquiloa – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tzitziquiloa

- Tzitziquiloa – https://cen.sup-infor.com/home/gdn/tzitziquiloa

- tzitziquiltic – https://nah.wiktionary.org/wiki/Tlatequitiltil%C4%ABlli:Frank_C._M%C3%BCller/Palabras_nah_TO

- Tzitziquilitl – https://www.malinal.net/lexik/nahuatlTZ.html