I have previously pondered over the next subject (and continue to do so) on a fairly regular basis. My ponderings are of course slanted by my own psyche (and a psyche that was constructed under the banner of Roman Catholicism no less). It has been stated that there were no Aztec Gods and that these “Gods” were in fact philosophical constructs created to bring into form various concepts and forces of nature. I have delved into this somewhat in a few previous Posts (1). These “Gods” were said to be created by the biases of the Spanish and their misunderstandings of mesoamerican theology (2) and thus they created Gods where before none existed. This is of course considered to be hogwash by others and that the term “teotl” does indeed refer to a specific being, much as the names Odin, Osiris, Dionysus or Jesus do (3).

- See Aztec Gods or States of Consciousness? and Xochipilli : A Force of Nature for some of these incoherent ramblings

- the study of the nature of God and religious belief

- who are all, interestingly enough, examples of the Dying-and-rising god. Quetzalcoatl also falls into this archetype.

However, it is never, as they say, “that simple”

teotl.

Orthographic Variants: teutl, theu, theou, teyotl

The “o” in teotl was pronounced much like a “u,” especially by the men. (Aldama y Guevara 1754)

Principal English Translation:

a divine or sacred force; a deity; divinity; God; something blessed, something divine (see Molina, Karttunen)

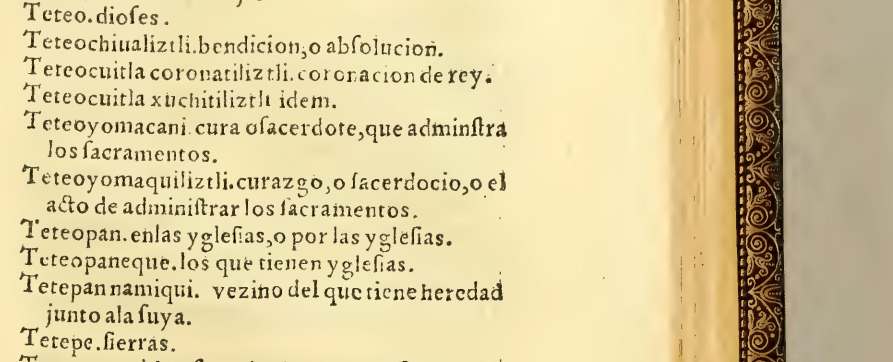

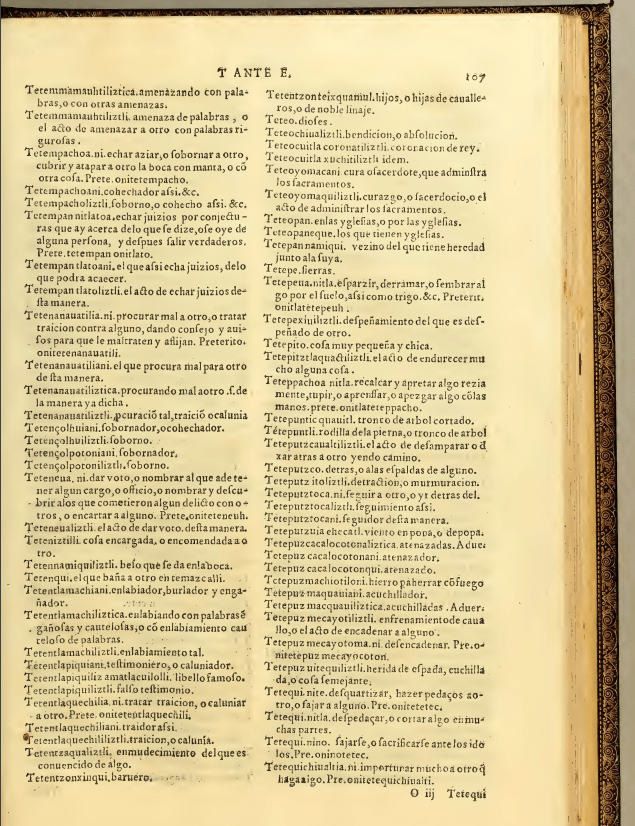

- (Molina 1571) : teotl. dios. (God)

- (Karttunen 1992) : TEŌ-TL pl: TĒTEOH god / dios (M) Z has the variant TIŌ-TL.

icel teutl dios = the only Deity, God (central Mexico, early seventeenth century) (Codex Chimalpain)

Now. My handy dandy Nahuatl dictionary does say that teotl does indeed mean deity (1) or God (with a capital “G”) which is backed up by their references (Molina 1571 & Karttunen 1992) but it also mentions the “force” of divinity or sacredness and those things (or people?) that are blessed or are made “divine” (2) because men themselves could become teteoh (4) and perhaps this is where the confusion arises.

- a supernatural being, like a god or goddess, that is worshipped by people who believe it controls or exerts force over some aspect of the world

- Apotheosis (from Ancient Greek ‘to deify’), also called divinization or deification (from Latin deificatio ‘making divine’), is the glorification (3) of a subject (man or object) to divine levels. “To be divine is to be unseparated from existence and all its creation. It is a feeling of belonging and very much our natural state. Mind, ego, beliefs, and selfishness all serve to take us away from this state”. It is possible for man to become like God, to become deified, to become god by grace.

- Glorification – also deification/apotheosis; exaltation (elevating someone (or something) in rank or power : the final removal of sin – sanctification “to set apart for special use or purpose” the glorification of the human condition can be a long and arduous process. “glorification is the work of God” (Rom 8:30)

- as could objects. Ixiptla (or teixiptla) could be people (or even cakes of amaranth seed – Amaranth and the Tzoalli Heresy) that were attired or constructed to represent a specific deity and for a specific purpose/festival (usually a sacrifice whether that be literal or metaphorical). “A teixiptla IS the being whom it embodies, it is neither an impression nor a representation of that being. A teixiptla cannot exist apart from the being it embodies”. (Basset 2015). In the case of amaranth cakes “by ingesting the tzoalli the Mexica affirmed their identity with (the god concerned). They testified to be his/her living manifestation in the world”. Does this count as becoming a teteoh? (or is just “becoming teteoh”?).

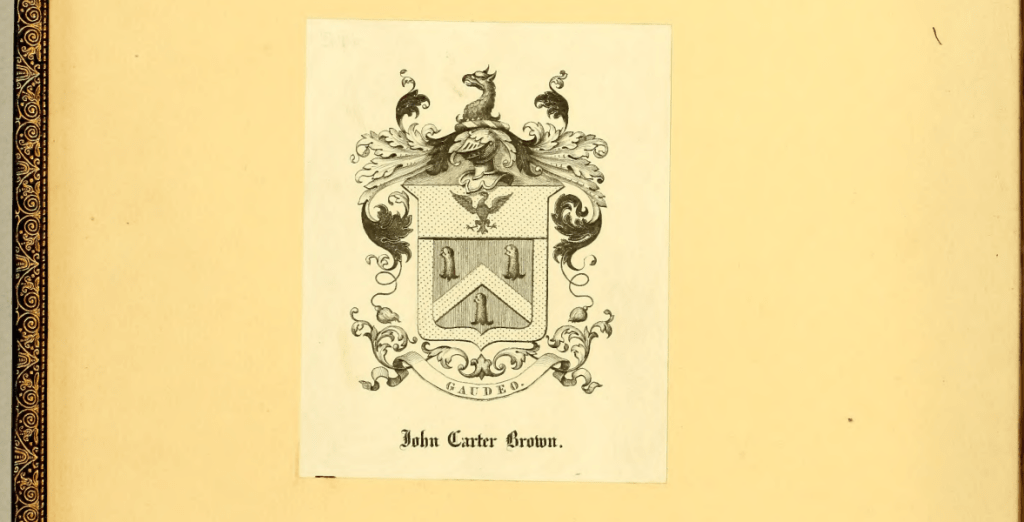

(as seen in the images below) Molinas’ (1571) definitions start of with diofes (dioses) “Gods” and quickly moves into religion with sacerdotes (priests), benedicions (blessings), abfolution (absolution – the pardoning of sins), curazgo (curates – parishes – the territory under the spiritual jurisdiction of the priest), and the administration of sacraments (1).

- Roman Catholic theology enumerates seven sacraments: Baptism, Confirmation (Chrismation), Eucharist (Communion), Penance (Reconciliation, Confession), Matrimony (Marriage), Holy Orders (ordination to the diaconate, priesthood, or episcopate) and Anointing of the Sick. The practise of these sacraments differ quite markedly from those of whose language this book is written in though (although….the Azteca had a State sponsored religion and deities (primarily Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc)…….and religion, like politics, regardless of its culture/source is all more or less the same. It all boils down to structure and control.

This is a lovely book. I can almost smell it. I however will have to settle for my pdf version.

From the personal collection of John Carter Brown

This sucker is old

Wait a minute……..Providence Rhode Island? 1846??

What in the H.P.Lovecraft ??????

Now there’s an eldritch force of nature if ever I saw one.

If you have made it this far without going insane or having your soul consumed we shall continue…

Wikipedia (1) states that “Teōtl ([ˈte.oːt͡ɬ]) is a Nahuatl term for sacredness or divinity that is sometimes translated as “god”. For the Aztecs teotl was the metaphysical omnipresence upon which their religious philosophy was based.”

- I don’t like to use Wikipedia as a Primary source. I do like to check it as it is often the first port of call when searching for knowledge online. A good Wiki entry will also have lots of referenced material which can be explored and which generally will lead you to other sources of unquoted information. Also I have to believe that people adding information to Wiki pages are people who have a specific interest and expertise in a niche subject.

No mention of specific Gods here though……..

It follows up with a description of teotl by Maffie (2014) which notes that teotl “is essentially power: continually active, actualized, and actualizing energy-in-motion… It is an ever-continuing process, like a flowing river… It continually and continuously generates and regenerates as well as permeates, encompasses and shapes reality as part of an endless process.”

Again, no mention of Gods just a description of force

Further down in the entry, a description by Bassett (2015) brings up the Gods of the Aztec pantheon (each being referred to as a teotl) and notes that each of them were “active elements in the world that could manifest in natural phenomena, in abstract art, and as summoned or even embodied by priests during rituals” and that “all these could be called teotl.” She connects being to force, Odin to lightning, Tlaloc to rain.

Things seem to be both unravelling and knitting together quite nicely.

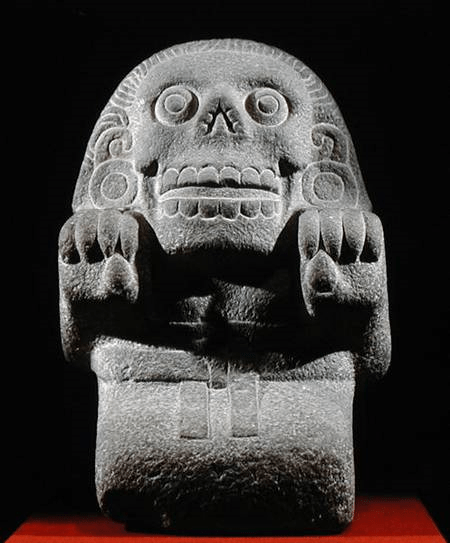

The author David Bowles (1) expands upon teotl (singular) and teteoh (plural). The teotl refers to the being i.e. Tlaloc. This makes sense. His explanation of teteoh muddies things a bit. He notes that “The main things classified as teteoh (plural) are the objects of worship for which temples (teocalli — “houses of teotl” — or teopan — “places of teotl”) were constructed”. It appears he’s referring in this case to statues and effigies of the various teotl. He goes on to note “Statues (2) of these teteoh show nearly always a humanoid figure (3) (sometimes with animal characteristics). Those idols were dressed, adorned, painted. They were carried for ritual purposes by a teomamahqui, a “carrier of the teotl,” whose title shows that the statues themselves were thought of as being—if not the gods themselves—representatives of various deities.” He goes on to explain that teteoh could simultaneously be both the being and the impersonal natural force much in the same way that Thor is both god and the force of thunder/lightning. “Teotl isn’t equivalent to the CHRISTIAN or MUSLIM notion of capital-G “God,” he continues “teotl” should probably be more broadly defined as a) sacred, b) supernatural, c) awful (as in either awe-inspiring or fear-inducing)” (4). He points out that the Aztec people never thought Cortés was a god (which is a current argument) “When 16th-century Nahuas called Spaniards “teteoh,” they meant, “these are clearly not normal human beings; they appear to have supernatural origins or abilities, and we should be wary of their awful, non-human ways.” In other words, “teteoh” could mean gods… but it could also mean something like DEMONS”.

- https://davidbowles.medium.com/nahuatl-note-teotl-vs-god-2b59376f4398

- This also included things such as carved wooden effigies and the amaranth dough, or tzoalli, effigies of teotl and not just carved stone statues. See Amaranth and the Tzoalli Heresy

- although in one ceremony an effigy of a mountain was made of amaranth grain (tzoalli) which was, at the end of the ceremony, broken into pieces and eaten by the participants. This offended the Spaniards as it too closely resembled the theophagy (god-eating) of the sacrament of the eucharist (or Holy Communion) whereupon bread and wine is transubstantiated (converted) into the flesh and blood of Christ which is then consumed by the devout (deeply religious/committed to the cause).

- For example, women who died in childbirth were said to become “cihuateteoh” (“female teteoh,” often rendered “goddesses,” though they were clearly different from the women-coded teteoh worshipped in temples i.e. Coatlicue, Xochiquetzal, Chalchiuhtlicue and others). The cihuateteoh would accompany the sun as it descends in the West, and were known to attack children and men sometimes.

Depictions of Cihuateteo

In Aztec mythology, the Cihuateteo were the deified spirits of women who died in childbirth. They were likened to the spirits of male warriors who died in violent conflict and as such they inhabited the same Heaven (1). Translated as “god-women,” these goddesses were considered the older sisters of the sun and to be powerful, benevolent (2) and munificent (3) ancestors.

- Florentine Codex : Book 6 : Twenty-ninth Chapter. Here it is told how they made goddesses of those women who died in childbirth. Called mocinaquetzque or “valiant women” (also written as mocihuaquetzque “brave women who rise up”) the spirits of these women transformed into cihuateteo “divine women” who accompanied the sun on its journey from noon onwards (the men accompanied the sun for the first half of the day), carrying him on a mantle of quetzal plumes into the western realm Cihuatlampa at sunset

- well meaning and kindly.

- characterized by or displaying great generosity..

If a mother died during birth the midwife would recite a prayer blessing the fallen warrior and urge her spirit to take its place with the Cihuateteo. In this prayer the midwife cried at the death of her patient, urging the parents to be glad that their child had died in childbirth because she would become a Goddess and accompany the sun as a brave one, a mocihuaquetzque.

My little one, my daughter, my noble woman, you have wearied yourself, you have fought bravely. By your labours you have achieved a noble death, you have come to the place of the Divine. …Go, beloved child, little by little towards them (the Cihuateteo) and become one of them; go daughter and they will receive you and you will be one of them forever, rejoicing with your happy voices in praise of our Mother and Father, the Sun, and you will always accompany them wherever they go in their rejoicing.

This prayer portrayed the Cihuateteo as benevolent beings, honoured and revered. Throughout this prayer, the Cihuateteo are referred to in militaristic terms. They are called “brave” and are extolled for “fighting bravely”.

As a group these goddesses caused widespread fear and trepidation in Aztec society, for they would return to earth and torment the living. On five specific days in the Aztec calendar (1), the cihuateteo descended to the earth. While on earth, they were considered to be demons of the night, and often haunted crossroads. Roadside shrines called cihuateocalli were often erected at crossroads to appease the cihuateteo and offerings of tamales and toasted corn were left for them. The cihuateteo were believed to steal children, cause madness and seizures, and induce men to adultery (Matos Moctezuma 2002) (2). The Aztecs greatly feared the days when these goddesses descended from the skies. The Cihuateteo were honoured in neighbourhood cihuateocalli built at the crossroads. They were given offerings of tamales and toasted corn, as well as bread shaped as butterflies and lightning rays.

- 1 Deer, 1 Rain, 1 Monkey, 1 House, and 1 Eagle

- It was said that they would cause possession, deformity and illness to whomever they caught in the open. Most notably affected by these spirits would be children, necessitating that they be hidden away. (Barnes 1997)

The Aztecs so feared these days that more of their moveable feasts (1) were dedicated to appeasing these goddesses than were dedicated to any other god or phenomenon.

- of the eighteen moveable feasts that Sahagún describes the third, eighth, and the twelfth are dedicated to appeasing these goddesses. Their appeasement rites were also a part of the festivals of the twelfth month called Teotl eco, and impersonators of the cihuateto were sacrificed during the eleventh month of Ochpaniztli.

As ascended their spirits so too did their bodies.

“…..when the mother died, her body became a holy relic and a depository of magical power, much in the same way as pieces and parts of the early Christian saints’ bodies were highly sought as relics in Europe. The Aztecs used the body parts of these women to help augment the supposedly prototypical male activities of bravery and fierceness. Young, unseasoned Aztec warriors sought the hair and fingers of the woman to insert them into their woven battle shields.” (Barnes 1997)

A normal, every day human whose spirit has been deified to the rank of teteoh and whose body (or remnants of it) now contain supernatural power. Holy relics gathered from the fallen bodies of the fiercest of warriors and carried into battle by the young and untested.

The Cihuateteo were literally the embodiment of bravery. Women dying in childbirth were the exemplars of courage, given the highest honour available to mortals.

It can then be posited that warriors were given the same status as women who died in childbirth (rather than that women were given the same status as warriors)

Aztec religion was not concerned with good and evil but with balance between chaos and order and as Bowles points out (about teteoh being a “force”) “Some nonhuman forces work for the good of humanity, but others have chaos as their goal”….. And Cortés, of course, was the most destructive teotl of them all…

This concern with balance between harmony and disharmony also affected the medical practices of the Aztec (as it did with nearly every aspect of their daily lives). Illness was caused by an imbalance of one form or another. This imbalance was corrected herbally and dietarily by using foods and medicines of certain temperate natures to counterbalance the imbalance and restore good health (both physically, mentally and/or spiritually).

The modern medicinal practices of Curanderismo (1) addresses illnesses according to their “temperate” values. This is a holdover from the Aztec times and revolves around the philosophies of balance within the universe (2). It is still generally claimed that this concept (3) was introduced into Mexico by the Spanish in the 16th Century and although this concept certainly held sway amongst European medical practices of the time the idea of balance was a central tenet of Aztec spiritual beliefs of the nature of opposing forces and how they were balanced within the universe.

- What is Curanderismo?

- Quelites : Quilitl

- the theories of Hippocrates including the temperate nature of things (ie cold in the third degree – such as is the nature of the herb verdolagas : purslane – Portulaca oleracea). The humoural theories of Hippocrates still held sway in European medicinal practices at this time. This is reflected in the Badianus Codex when the Aztec term for melancholy was translated into the more Spanish term “black blood” and by doing this changed the entire dynamic of understanding the condition. These concepts were similar to those already in use by the Azteca and would have added to a fairly seamless transition and adoption in the medical practices of the Spanish.

So.

Teotl?

God? or Force of nature?

References

- Aldama y Guevara, Joseph Augustin de; (1754) Arte de la lengua mexicana (Mexico: BIbliotheca Mexicana)

- Barnes , William L. + (1997) “Partitioning the Parturient: An Exploration of the Aztec Fetishized Female Body.” Anthanor XV: 15-27.

- Bassett, Molly H. (2015). Aztec Gods and God-Bodies. The Fate of Earthly Things. University of Texas Press. doi:10.7560/760882. ISBN 9780292760882.

- Codex Chimalpahin: Society and Politics in Mexico Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Culhuacan, and Other Nahuatl Altepetl in Central Mexico; The Nahuatl and Spanish Annals and Accounts Collected and Recorded by don Domingo de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin, eds. and transl. Arthur J. O. Anderson and Susan Schroeder (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997), vol. 2, 130–131.

- Gingerich, W. (1988). Three Nahuatl Hymns on the Mother Archetype: An Interpretive Commentary. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 4(2), 191–244. doi:10.2307/1051822

- Karttunen, Frances E. (1992). An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Key, Anne. Death and the Divine: The Cihuateteo, Goddesses in the Mesoamerican Cosmovision. Diss. California Institute of Integral Studies, 2005.

- Klein, Cecilia. “The devil and the skirt: An iconographic inquiry into the pre-Hispanic nature of the Tzitzimime”. Ejournal: Revista estudios de cultural Náhuatl. 31 (2000): April 20, 2003,

- Maffie, James (2014). “Teotl”. Aztec Philosophy, Understanding a world in Motion. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1-60732-222-1.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo; Solís Olguín, Felipe R., eds. (2002). Aztecs. London: Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 9781903973134. OCLC 50525805.

- Molina, Alonso de, (1571). Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana part 2, Nahuatl to Spanish, f. 101r. col. 2./ Fray Alonso de Molina ; estudio preliminar de Miguel Leon-Portilla. Mexico [D.F.] : Porrua

- Sahagún, B. D. (1577) General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex. Book VI: Rhetoric and Moral Philosophy. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified] [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667851/.

- Sullivan, Thelma D. and Timothy J. Knab. A Scattering of Jades: Stories, Poems, and Prayers of the Aztecs. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. 2003.

Websites

- David Bowles – https://davidbowles.medium.com/nahuatl-note-teotl-vs-god-2b59376f4398

- Teotl (definition) – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/teotl