“We must repeat it: Mesoamericans do not plant corn, Mesoamericans make cornfields. And they are different things because corn is a plant and the cornfield is a way of life. The cornfield is the matrix (womb) of Mesoamerican civilization. If we really want to preserve and strengthen our deep identity, not only agroecological but also socio-economic, cultural and civilizational, we must move from the corn paradigm to the milpa paradigm: a complex concept that includes corn but goes beyond it…..

…“The strength of the milpa is not in the productivity of the corn or the beans or the pumpkin or the chili or the tomate verde (tomatillo) measured separately. Its virtue is in the synergistic harmony of the whole.”

Armando Bartra

Now. Lets get onto the actual subject.

We briefly looked at the “Gold Standard” diet, as far as Western allopathic medicine is concerned, the Mediterranean Diet, in my previous Post A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 1.

https://www.health.qld.gov.au/

To briefly recap, the Mediterranean diet resulted from the work of Ancel Keys known as the Seven Countries Study. The study began in 1956 and with results first being published in 1978 the study looked at the diets in Finland, Greece, US, Italy, Yugoslavia, Netherlands and Japan and set about to investigate links between coronary heart disease mortality and lifestyle factors. Regardless of the flaws in the study and the manipulation of data (see my last Post) what resulted from the study was a series of dietary, lifestyle and cultural recommendations conducive to good health.

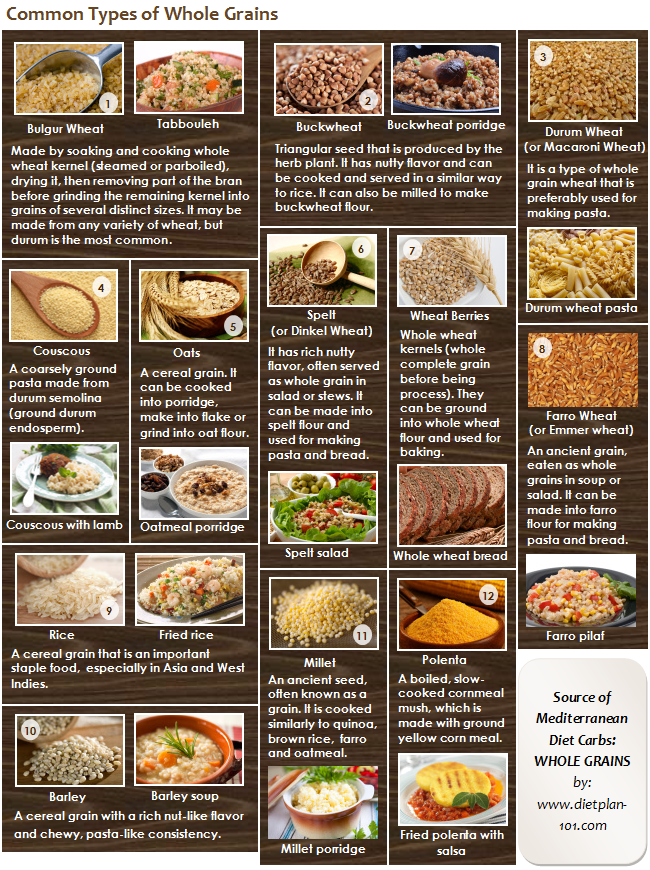

Some of the foods that would be included in a Mediterranean diet

- Red meat – Pig, beef, goat, sheep

- Birds – Chicken, duck, quail, and eggs

- Sweeteners – honey (bee), sugarbeet

- Dairy – milk (cow, goat, sheep), cheese (feta, ricotta, cottage), yoghurt

- Alcohol drinks – Wine (preferably red)

- Other drinks – Fruit juices

- Fish and seafood – blue (oily) fish (sardine, anchovy, small mackerel, salmon.)

- Starchy tubers – carrot, parsnip, turnip, beetroot

- Whole grains – oats, barley, rye, wheat (whole wheat bread, pasta, including semolina and couscous), rice, millet, buckwheat

- Oils – olive oil (particularly cold pressed extra virgin olive oil), walnut oil, hazelnut oil, butter

- Fruits – citrus (grapefruit, orange, lime) pear, apple, lemon, grape, figs, blueberry, pomegranate, quince, dates

- Nuts and protein rich seeds – walnuts, chickpeas, lentils, almond

- Vegetables – broccoli, chard, spinach, cucumbers, lettuce, cabbage, turnip, celery, peas, eggplant, cauliflower, onion, garlic, beet, carrot, parsley, leek, mushrooms, radish, olives, capers, asparagus, artichoke, fennel

- Spices – coriander seed, saffron, bay leaf, black pepper, sumac, fenugreek seed, fennel seed, cinnamon, nutmeg

- Aromatic herbs – basil, oregano, thyme, rosemary, sage, garlic, parsley, lovage, mint, dill, chervil, chives, tarragon, savory

- Flowers – borage, lavender, rose, chicory, elder, chamomile, calendula, orange blossom

- Foods from the Americas (introduced after the 1500’s) – tomato, pumpkin/squash, zucchini (and their flowers), paprika, Aleppo pepper, (un-nixtamalised) corn (polenta)

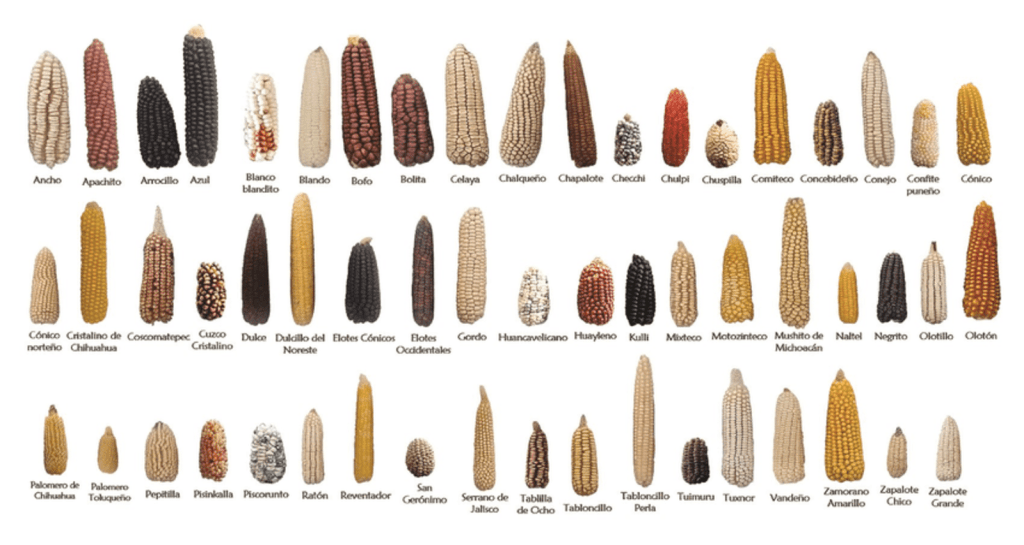

What I would like to investigate now however is a similar series of dietary, lifestyle and cultural recommendations conducive to good health coming from a different aspect and one that would have (and still can) exist completely in isolation and without non-American imports. Interestingly enough the Mediterranean Diet as espoused by Keys (and as shown in the diet pyramid above) included American imports. It was 1956, more than 400 years since the foods of the Americas had started to make their way into the rest of the World (and firmly implanting themselves in many places) and I can’t help but wonder what the diet of these peoples would have looked like without ingredients such as potatoes, tomatoes and avocados (I’m only mentioning crops as shown in the pyramid above). In the series of images above (Fruits : Vegetables : Whole grains) only a couple of items have Mesoamerican provenance (tomato, avocado, and polenta – which is made from un-nixtamalized corn/maíz), the rest of the foods would have been available (particularly in Italy) long before contact with the Americas. The Mediterranean Diet at the time of the Romans would have been very nutritious and health giving but at the time of Keys’ work these same Mediterranean folks had a much greater range of choices when it came to fruits and vegetables. The only major wholegrain introduced from the Americas was of course maíz. (Chia, amaranth and quinoa are a category in and of themselves and they will come up later on)

The diet of prehispanic peoples was an extremely healthy one and consisted of a wide variety of options. It has been noted that the meal of an average Aztec warrior consisted approximately of 700g of corn, 150g of beans, 60g of squash, 100g of tomate verde (tomatillos), 100g of amaranth, 25g of red pepper 50g of green pepper, 150g of fish, and 200g of nopales. (Carmona Rosales 2021). As you can see this meal is largely vegetarian and it may be that the diet (or average meal) of the average peasant may not have been as good (particularly with regards to the fish, which would have been dependant upon location as not everyone lived on the shores of a lake or the coastline of the ocean). There would however have been a great variety of locally and seasonally available plant based foods.

The choices however are great and varied. Prehispanic peoples did not want for lack of choice. Depending on the location a mesoamerican may have had access to any of the following options.

Meat, even though the prehispanic mesoamericans had no large domesticated meat animals (cows, sheep, pigs, goats etc) they did not lack for sources of animal based protein. Some of these protein sources included….

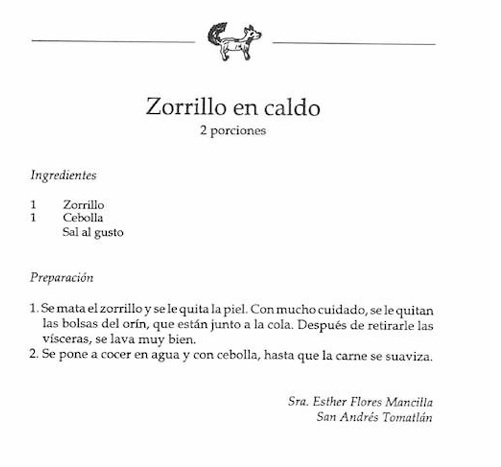

agoutis, squirrels, armadillos, rabbits, coyotes, weasels, coyametls (peccary – also called javelina), wild boars (jabali), hares, lagarto (maned wolves), jaguars, wild cats, lynxes, raccoons (mapache), martens, otters, black and brown bears, tapirs, badgers, ocelots, gophers, possums (tlacuache), tepezcuintles (lowland paca), deer, foxes, skunks (epatl – zorillo : For a recipe see Skunkweed and the Skunk) and we mustn’t forget the Xoloitzcuintle (a hairless dog native to Mexico)

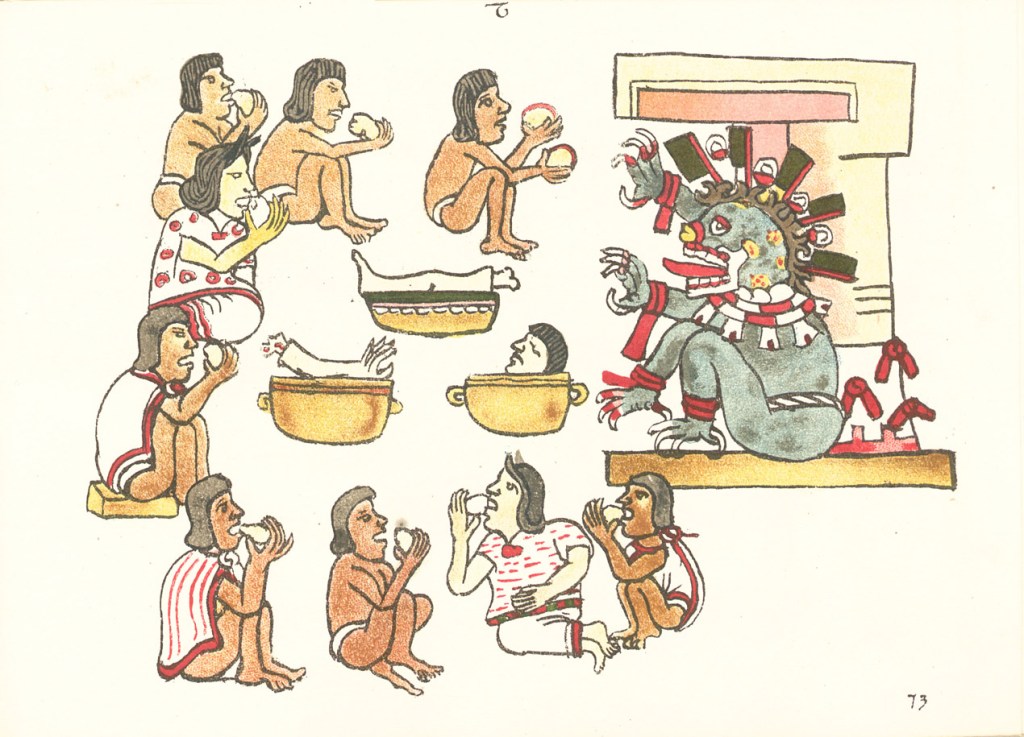

Another interesting protein source of animal origin is that of human flesh.

Ritual cannibalism was said to be enacted through the consumption of the dish Tlacatlaolli, a dish made of nixtamalized corn kernels and the flesh of captives (Gifford-Gonzalez 1999) (Morán 2016). This was not an everyday source of meat consumption though (the key word here being “ritual”). The corn used in the dish is also used to this very day in a dish called “pozole”. Pozole is also said to have been initially created from human flesh although there are disagreements with this. Pozole is also said to have been made from the flesh of the Xoloitzcuintle dog but according to information released by the federal government’s Agricultural Market Development and Marketing Services Agency, the meat that was actually used was from itzcuintlis, or more specifically the tepezcuintle (lowland paca).

Tlacatlaolli and pozole are two different dishes linked through the use of the nixtamalized maize kernel cacahuazintle which is often called hominy.

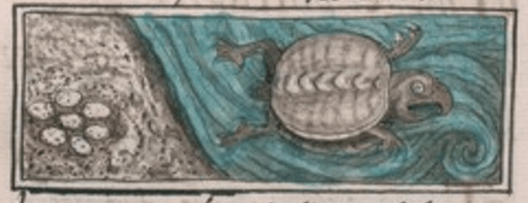

Reptilian sources of protein

iguana (you can also eat the eggs of the iguana) and other lizard, snakes, crocodiles, cayman

For some interesting recipes using these unusual protein sources try to get your hands on this book

Fish and seafood

Pescado (fish – numerous varieties – too many to name – that differed upon the location i.e. lake, river or coastal/ocean), pulpo (octopus), langostino de río (river prawn), acociles (small freshwater crayfish) See 31 Alimentos que México dio al mundo : 31 foods that Mexico gave to the World for more detail. Turtles (ocean – and their eggs), shellfish and molluscs

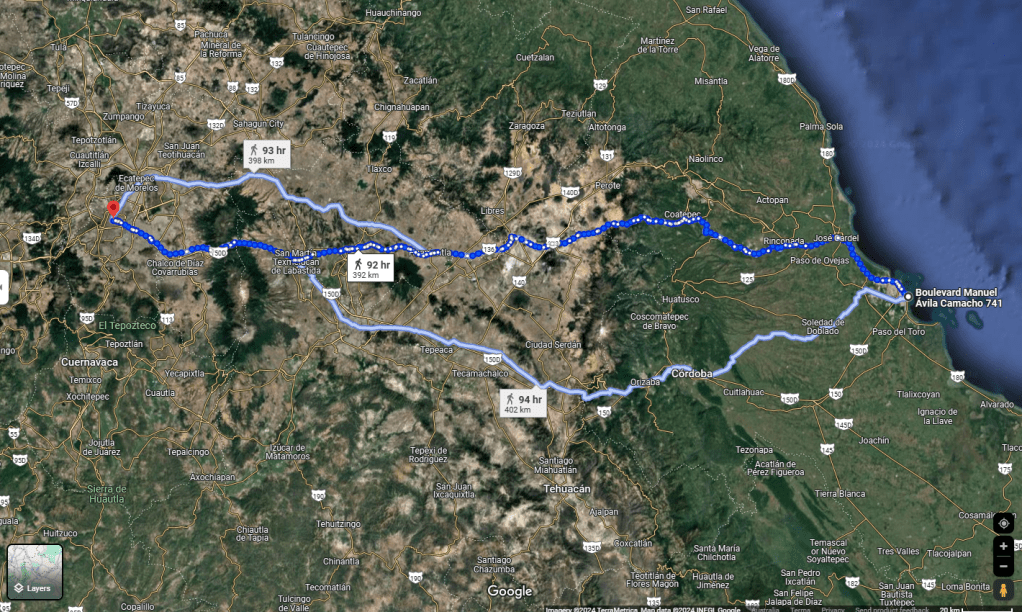

There is a legend (?) that Moctezuma II loved fish so much (and fish from the sea in particular) that he would have it delivered to him by overnight courier from the ocean at Mexico’s Gulf coast from the waters (probably around Cempoala) in the area now known as Veracruz.

These couriers were an elite group of runners called paynanis (painanis). They were chosen from the strongest runners in the land and received specialist training. Paynanis typically carried correspondence for the wealthiest nobility and military dispatches in time of war. They had diplomatic immunity and were respected even by the rival tribes (although “disrespecting” an Aztec envoy usually ended in violence delivered upon you and your people by the Mexica so “respecting” likely meant fear of reprisal).

It is also said that they performed not only this vital mail service but would also transport exotic fruits and foodstuffs for the regent; in this case they carried fresh fish from the ocean over a distance of 350 to 400 kilometres into Tenochtitlan. It has been calculated that it took approximately 40 runners in relay, travelling about 11 kilometres each, running at a speed of about 10 kilometres every 38 minutes (15.8 km per hour) to travel the distance in only 24 hours. Quite a feat. Some say however that this is “only a legend” and that it would be “impossible to transport fresh seafood from the Port of Veracruz to Mexico City on foot without refrigeration and avoiding spoilage” and that “considering the shaking involved in running for two days, this most definitely had ruined the texture of the fish”. Pfft. Killjoys.

An interesting story from Xalapa (1) in Veracruz is that of Macuiltépetl (2) a hill located within an Ecological Park (3) that lies “smack dab in the middle of the city”. In Aztec times, there were no roads with signs that said, “Ocean, this way.” These runners had to rely on natural landmarks. The easiest landmarks to spot were mountains and big hills. So the hill in what is now the city of Xalapa happened to be the 5th mountain they would look for to know that they were almost to the ocean. This actually bears some truth as although there were maps in the time of the Aztecs these maps did not look like a map as we understand them today but were more of a pictoral story book that drew the journey in pictures and included images of various landmarks.

- Xalapa or Jalapa officially Xalapa-Enríquez is the capital city of the Mexican state of Veracruz and the name of the surrounding municipality.

- In the Náhuatl language (which was spoken by the Aztecs) this name means, “5th Mountain.” Other less imaginative people think that the name refers to the fact that the hill had five promontories that stood out from some point on the horizon and that the correct name should be “The Mountain of the Five Peaks”

- Parque Macuiltépetl

The above is an image of a portion of a map as might have been found during Aztec times. It shows several towns, hills and rivers.

I do not think running fish from the coast to be an unreasonable feat. 24 hours outside of the refrigerator does not necessarily a rotten fish make. These runners were also relegated another task to satiate the Tlatoanis cravings for ice-cream. Well not ice-cream exactly but the Mexican dessert known as nieves (or “snow”). They would travel to the nearby mountains of Popocatépetll or Iztaccíhuatl and collect ice which would then be packed in bags insulated with ixtle fibre and then run the approximately 100 kilometres back to Tenochtitlan. The ice would then be crushed and sweetened with honey or various fruit syrups before being eaten. Some would also be placed in clay jars which were then packed into boxes filled with ice and salt and then transported to the markets at Tlatelolco for sale to discerning nobles.

So. Fish from the coast? No great stretch of the imagination if you ask me. We tend to sorely underestimate the sophistication of this culture (we do like to think we are so clever).

Lacustrine protein sources (aside from fish)

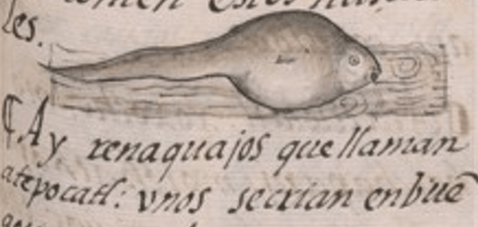

- atepocatl/renacuajo (tadpoles). See Vitamina T : The Tlapique. Cousin of the Tamal. (the axolotl also comes up in this one),

- cueyatl/ranas – frogs,

- ajolote/axolotls : axolotls also have medicinal utility – Xochimilco and the Axolotl

Birds

- Guajolote (turkey)

- huevos (eggs)

- numerous waterfowl (ducks, geese, cranes, pelicans)

- quails and other ground dwelling birds

Insects and their larvae

Gusanos de Maguey (Maguey Worms)

- Chinicuiles – red maguey worms (also called chilocuiles and tecoles) – larvae of Comadia redtenbacheri (a moth) See Pulque Curado : Tecolio (1)

- Meocuiles – white maguey worm – larvae of Aegiale hesperiaris (a butterfly)

- Chapulines (Grasshoppers) (1)

- In my Post 31 Alimentos que México dio al mundo : 31 foods that Mexico gave to the World you’ll find more info on tecoles, chapulines, and jumiles

Other insects

- Escamoles (Ant Larvae) larvae and pupae of ants of the species Liometopum apiculatum and L. occidentale var. luctuosum. See Edible Insects : Escamoles for more detail.

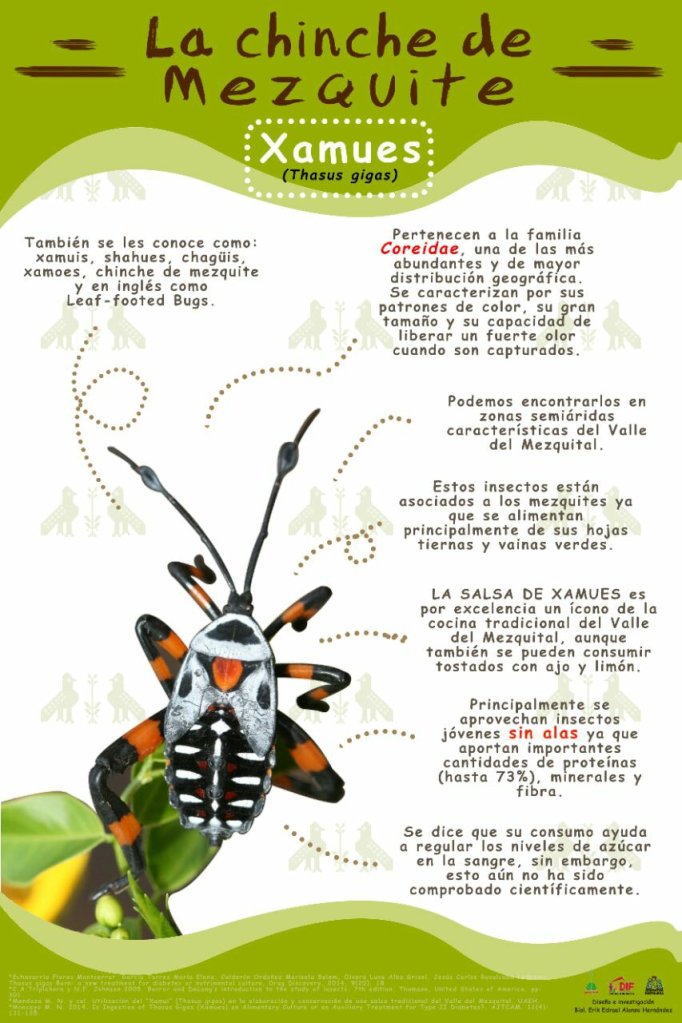

- Jumiles (1) (Nahuatl – xomilli) a small stink bug (Euschistus taxcoensis) native of the states of Guerrero and Morelos.

- Hormigas Chicatanas (Atta Ants) a species of leaf-cutter ant belonging to the Formicidae family

- Hormigas de miel – Honey pot ants (Myrmecocystus mexicanus). See Edible Insects : Hormiga de miel : Honeypot ants for more details.

- Ahuautle – eggs of the insect called Axayácatl (Corixidae species) – commonly called water boatmen – both the insect and its eggs can be eaten (see Edible Insects : Axayácatl (Ahuautli) for more detail)

- Chahuis – (xamoes) – a variety of edible insects within the order Coleoptera

- Cuetlas (chiancuetlas) – butterfly larvae that live on the chia, jonote, cuaulote and tlahuilote plants. See Edible Insects : Cuetla for more detail

- Cupiches – larvae of the strawberry tree butterfly (Charaxes jasius). They are collected as cocoons and the chrysalises are toasted on the comal. In the area of Lake Pátzcuaro they call them chamas, the Zitacuarenses call them huenches, and in other parts of Michoacán they call them conduchas.

- Cuauhocuilines (Titococci) – wood-boring worms, also called canalejos, titocos and cuauhocuilines which in the south of Mexico are prepared in a broth with corn, avocado leaves and epazote

- tsats (zats) – I have seen this refer to the larvae of a butterfly called cuetlas (the larvae that is, not the butterfly – see above listing) and the larvae of the Proarna species (a type of cicada) found in the bark of capulín or guamúchil trees (Pithecellobium dulce).

This is by no means a complete list

- In my Post 31 Alimentos que México dio al mundo : 31 foods that Mexico gave to the World you’ll find more info on tecoles, chapulines, and jumiles

Are insects a viable source of protein?

It appears so

The range of insects available commercially continues to expand

A few studies showing medicinal uses of insects globally.

Insects have been employed in some countries as a nutraceutical food for a long time (Costa-Neto etal 2006). A few examples of this include; in Nigeria, crickets (Brachytrupes membranaceus) are used as a food source to promote mental development and pre- and post-natal care (Banjo etal 2009). In Asia, the Chinese beetle (Ulomoides dermestoides) is often used as an alternative form of treatment for diseases, such as asthma, arthritis, and tuberculosis (Costa-Neto etal 2006). In Brazil, the same species is used as a stimulant and to treat eye irritation and rheumatism (Costa-Neto etal 2006). Some species of cockroaches and ants are used to treat asthma and are consumed in the form of tea in different countries, such as Brazil and India (Costa-Neto etal 2006). So far, most studies have been carried out in vitro or using animal models. Results show that edible insects may provide gastrointestinal protection, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, antibacterial activity, immunomodulatory effects, blood glucose and lipid regulation, hypotensive effects, and a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease (Nowakowski etal 2022)(Roos & Huis 2017)

Dairy : Not present in Mesoamerica

Whole grains

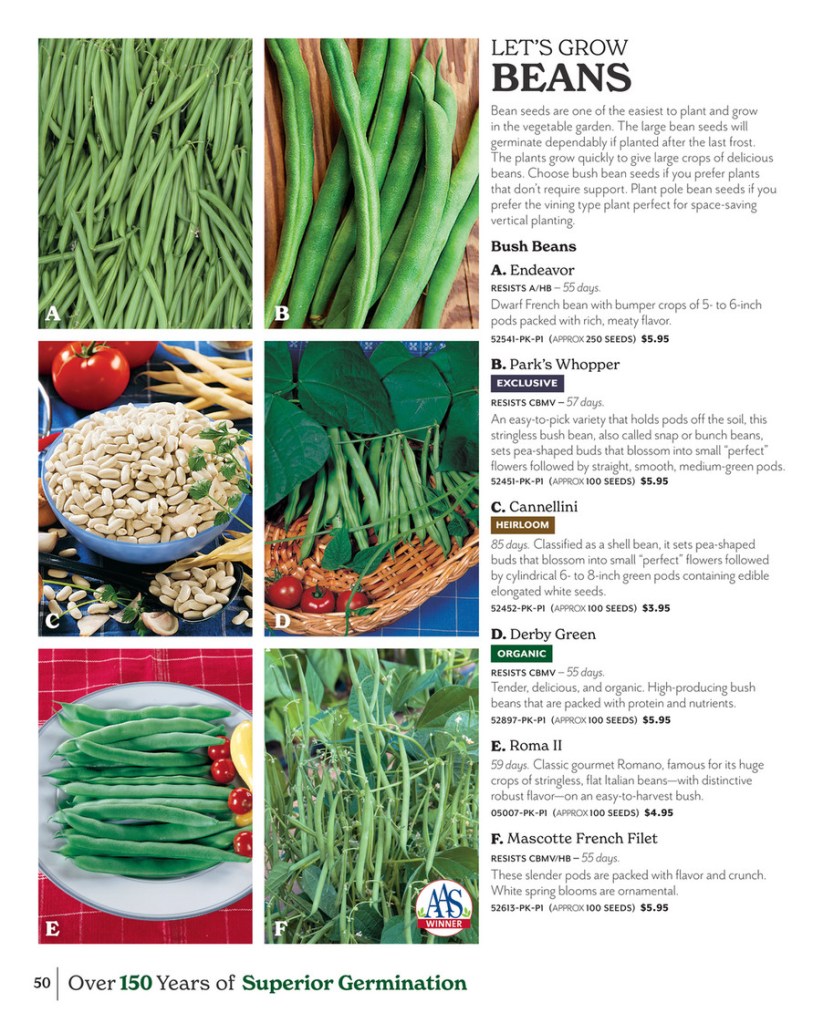

One thing that should not be overlooked is the trio of maiz y frijoles (corn and beans) and squash. This combination of both agricultural polyculture and dietary intake (often referred to as the “Three Sisters”), which was available even to the poorest in society at the time, was able to supply a complete amino acid profile and provide the necessary calories (and almost all the required vitamin/mineral content) required for perfect health (Mt.Pleasant 2016). With the addition of the pseudo grain amaranth (or quinoa – depending on your location) this diet essentially totally eliminated the need for meat based protein.

Maiz – Corn (nixtamalized – treated with an alkaline solution) – ground into a dough called masa to make tortillas/tamales or left whole to make pozole (which is different from pozol). Corn was the primary grain of mesoamerica. Wheat had yet to be introduced (the Spanish bought wheat to Mexico in the early 1500’s) and although some varieties of wild rice existed (although much further north in regions such as Canada, the Great lakes region which shares a border with Canada, and some parts of Texas and Florida) it was a distant relative to rice as we understand it today and which was introduced from Asia via the Colombian exchange sometime in the 16th and 17th centuries). Corn itself is very interesting and its treatment (nixtamalisation) required to make it a useful and nutritious grain forms a whole subject of study which was not understood by those who first exported the grain and believed it to be a far inferior foodstuff as a result of this lack of knowledge of its processing. They were of course completely incorrect in this . For more info on this process see Nixtamal.

Protein rich seeds : chía, Huauhtli or amaranto (amaranth) (1), quinoa, cacahuate (peanuts) (2), piñón (pine nuts), (sunflower seeds),

- Quinoa (Chenopodium) Quinoa is native only to a relatively small region of the Andes mountains in South America

- Huauhtli – amaranth (Amaranthus) (1)

- Chia (Salvia)

- semilla de girasol – Sunflower (Helianthus)

- pepita de calabaza (pumpkin/squash seeds)

- Guaje Leucaena leucocephala.

- Amaranth is another nutritional powerhouse. It is a complete protein in and of itself (Zhang etal 2023) (Sidorova etal 2023). It can be eaten as a fresh green vegetable and for its seed (See Nutritional Profile of Amaranth). It is also a medicinal plant (See Medicinal Qualities of Amaranth) and was one of the most demanded “grains” by the Aztecs as a tribute item. The Spanish did not like this grain (particularly its religious/spiritual aspects) and did their damnedest to eliminate it (See Amaranth and the Tzoalli Heresy)

- often thought to originate from Africa the peanut is native to South America, east of the Andes, around Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, and Brazil (Seijo etal 2007)

Guaje pods grow from a tree known as Leucaena leucocephala.

Beans (frijoles)

Legumes

exotl/ejotl = ejotes – fresh beans

etl – frijoles – dried beans

- Kidney Bean,

- Pinto Bean,

- Navy Bean

- Cannellini,

- Haricot Beans

- French Beans

- Pole Beans

- Bush Beans

- Black Beans,

- Borlotti Beans

- Phaseolus. lunatus: Lima Beans

- P. coccineus: Runner Beans, Flat Beans

- P. acutifolius: Tepary Bean

- Arachis hypogaea : Peanut (Groundnut)

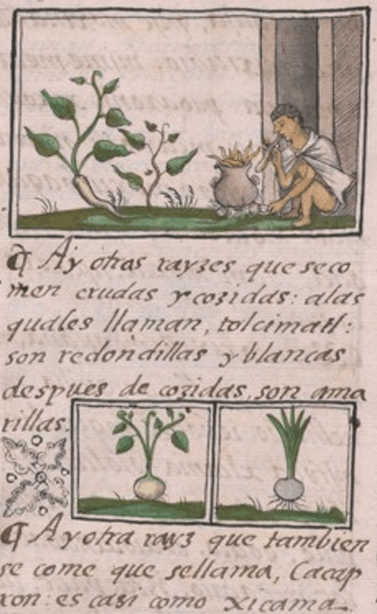

Roots/Tubers

- Acocoxochitl – Dahlia species (edible tubers) – Acocoxochitl : The Dahlia

- Camotli (camote) Sweet potato – Ipomoea species

- chayotextle or chinchayote (1)

- Cuauhcamohtli (Cassava) (also Yuca and manioc) (not yucca) – Manihot esculenta

- Jerusalem artichoke – Sunchoke – Helianthus species

- xīcamatl (Jicama) – Pachyrhizus species

- Chayotextle or chinchayote is the edible tuber of the chayote (Sechium edule)

Vegetables

- nopales : The Nopal as Food. The nopal is also used medicinally – The Medicinal Qualities of Nopal Cactus

- calabaza (pumpkins – winter squash)

- chayote

- chilacayote Cucurbita ficifolia) a species of squash, grown for its edible seeds, fruit, and greens

- Curcurbita species (Summer squash)

Aside from being both food and medicine, the nopal is an integral aspect of Mexican history and culture. Creation legends of Mexico involve the nopal and the cactus itself can be found in the centre of the Mexican national flag. Another xeric plant integral to the personality of Mexico is the maguey or agave (called metl by the Aztecs). This plant provides food, drink (1) and medicine as well as several legends.(2)

- as well as several layers of alcoholic drink, the fresh sap can be fermented into a beer strength alcohol and the juice squeezed from the baked plant can be fermented and the distilled into several drinks with much higher alcohol content. No doubt you’ve heard of two of them, tequila and mezcal.

- Mayahuel and the Cenzton Totochtin.

Squashes and Pumpkins

Nightshades

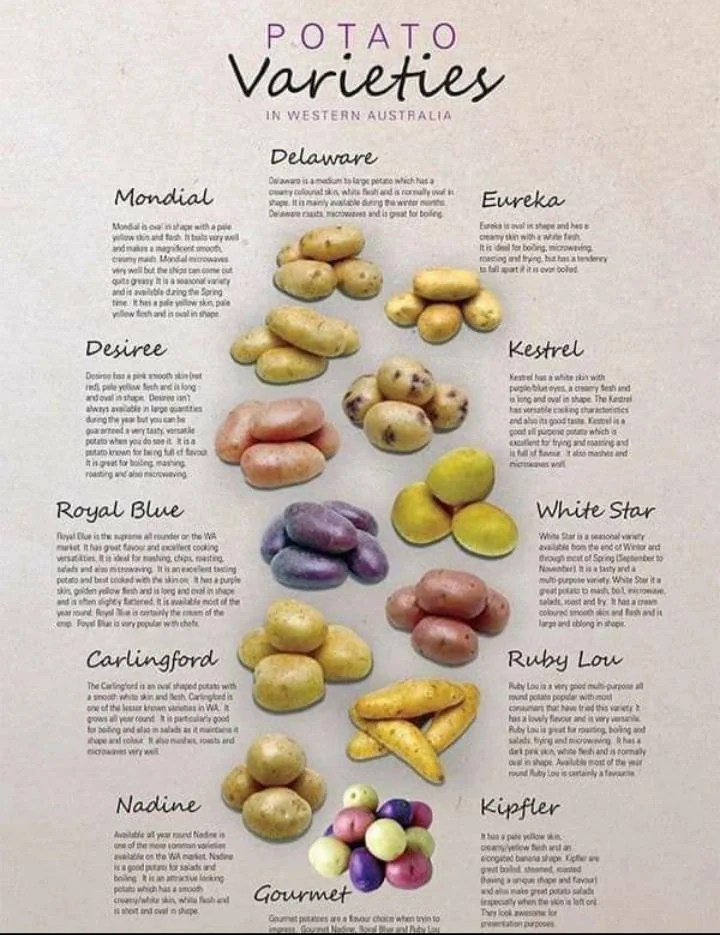

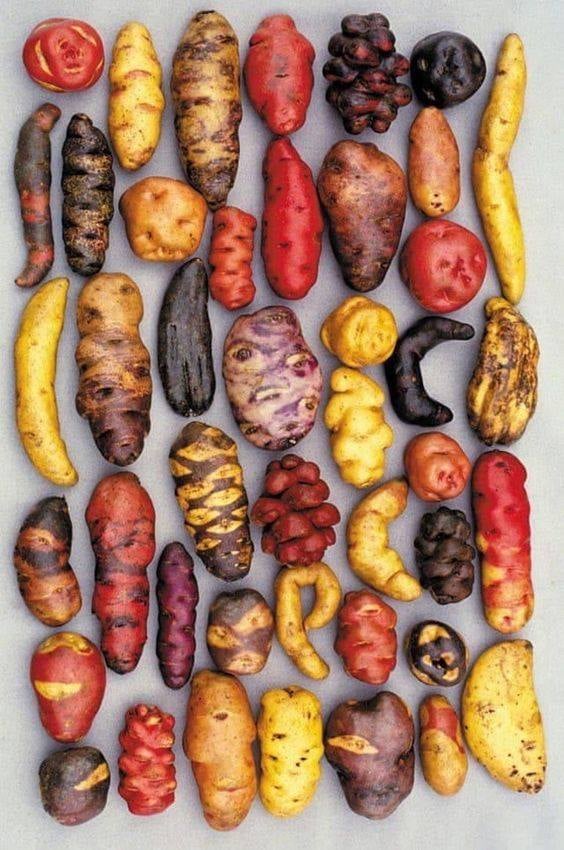

- Potato – Solanum species

- Jitomate – (red) Tomato – Solanum species

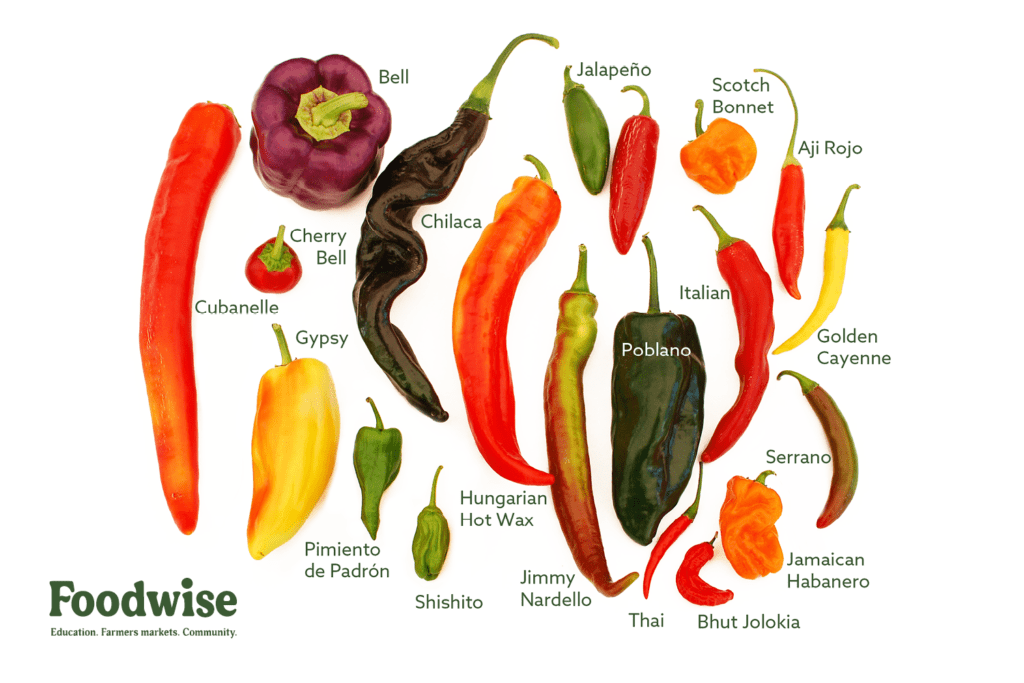

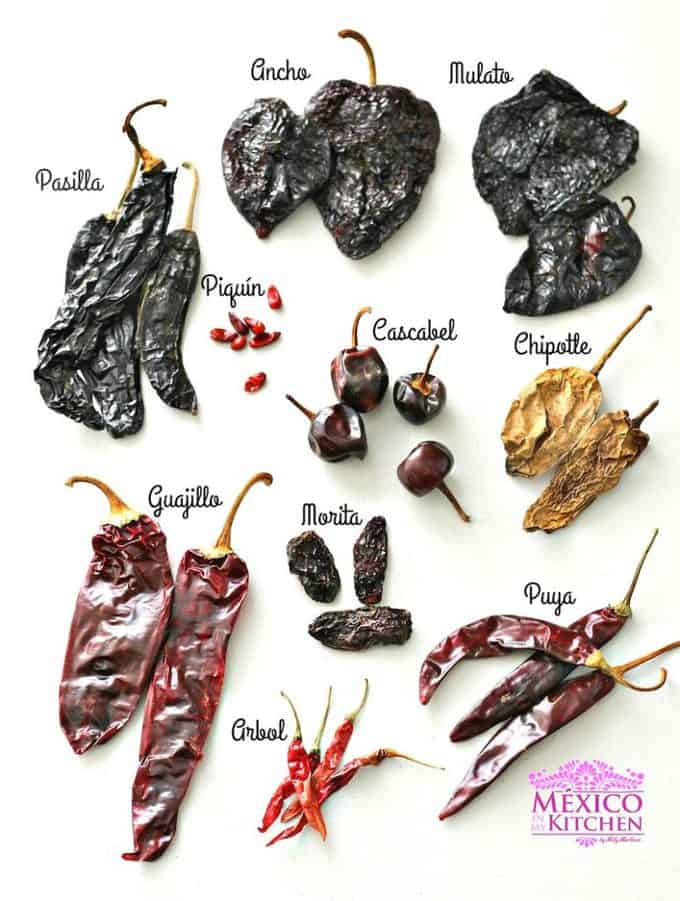

- Chiles and Capsicums (what an American might call a “Bell” pepper or pimiento) – Capsicum species

- Tomate verde – miltomate – Tomatillo – Physalis philadelphica

An extremely valuable Family that supplies us with tomatoes (including tomate verde), chiles/capsicums, potatoes and even tobacco (aside from its ritual use, the “value” of using tobacco is debateable.

You are more likely to find most of these at your local market (than you are the potatoes or tomatoes shown earlier)

Even the dried chiles are becoming easier to find outside of Mexico (and I’m in Australia where I can find all of these – imported fromn Mexico por supeusto)

The Queen of Tomatillos : Reina de Malinalco

Tomate verde (tomatillos) are harder to find. I’ve only ever seen them twice in Australian stores. Usually I have to grow them myself (or rely on canned varieties – which is a last resort)

Fruits

- Pineapple (Ananas)

- Guava (Psidium and Acca)

- Passion fruit (Passiflora)

- Papaya (Carica and Vasconcellea)

- Cherimoya – Annona cherimola

- sugar-apple – Annona squamosa

- soursop – Annona muricata

- Ciruelo (hog plum) – Spondias mombin

- Pawpaw – Asimina species

- Mamey

- Nanche

- Tejocote

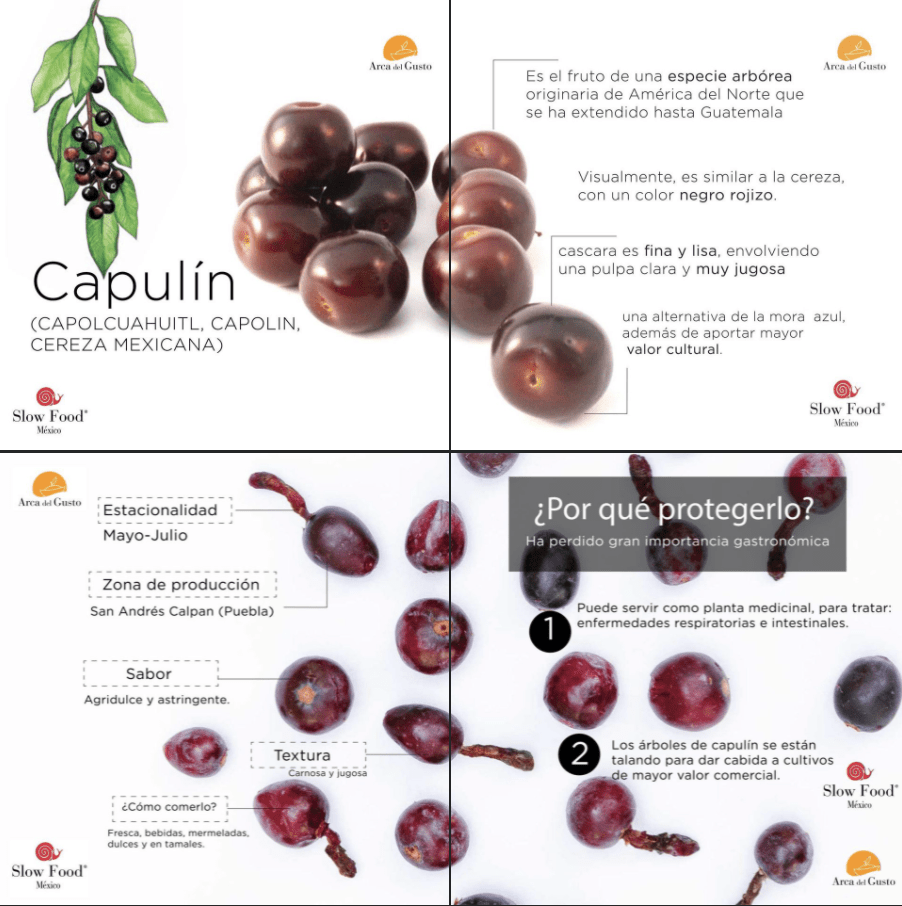

- capulin

Cactus fruits

- Biznaga – Ferocactus secies – pulp of cactus used to make acitron : Cooking Technique : Acitronar (and by default the Biznaga and Acitrón)

- Garambullo – Myrtillocactus species – fruit : Frutos de Cactus : Garambullo

- Nopales (Opuntia species cladodes “leaves”) – green vegetable

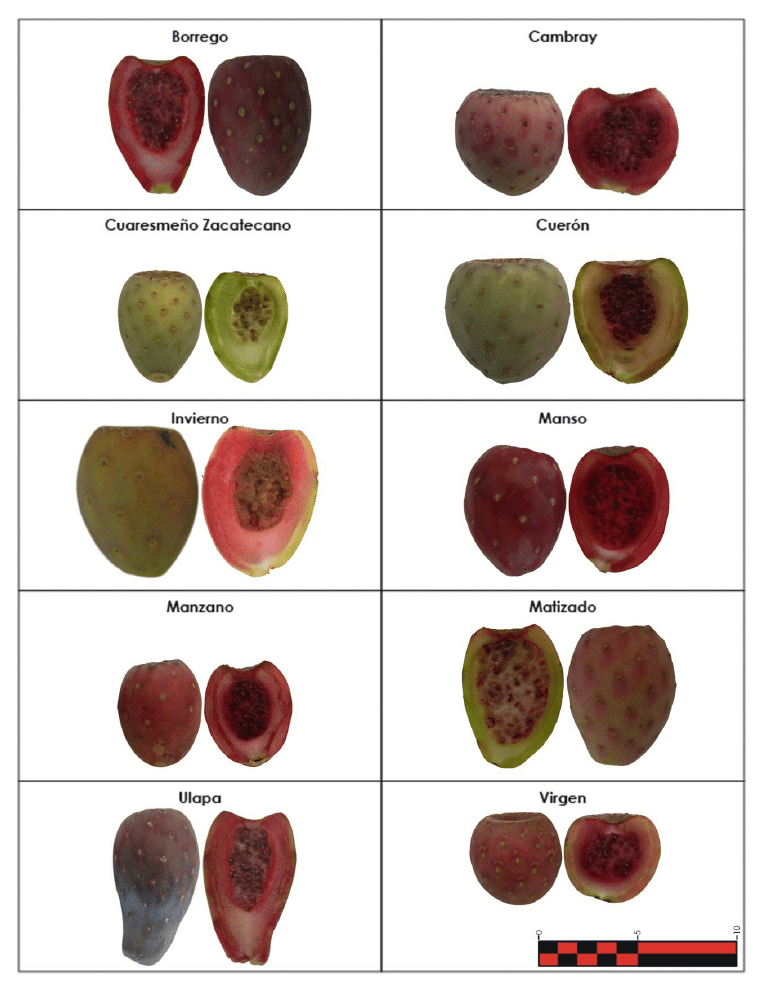

- Tuna – Prickly pear – Opuntia species – fruit

- Pithaya (Pitaya) Dragon fruit – Hylocereus and Stenocereus species

- Xoconostle – “sour” Opuntia species – fruit : Frutos de Cactus : Xoconostle and Medicinal uses of Xoconostle

The nopal as a vegetable

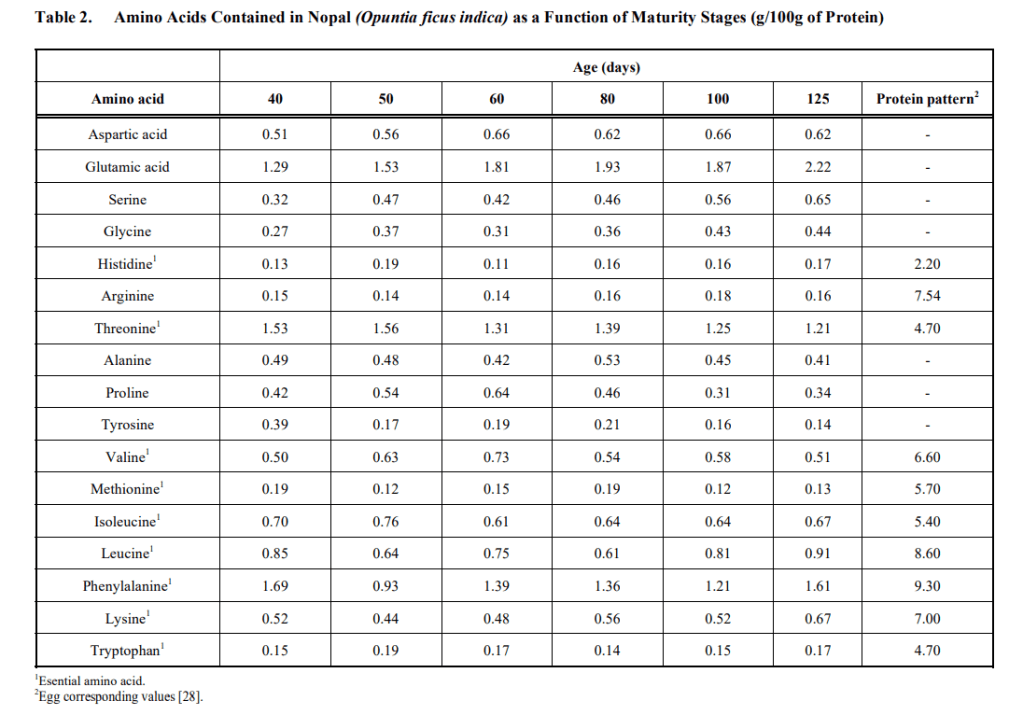

Nutritional content of nopales

The data collected by Hernández-Urbiola (et al 2011) suggests that the best age to harvest and consume pads is at 135 days because of its elevated calcium content.

Carbohydrates are the main component in prickly pads and carbohydrate content of old prickly pads showed significant increases from day 40 to day 135. (Stintzing et al 2005)

In relation to the amino acid content, analyses showed that nopal contains 17 different amino acids, nine of which are considered essential, and showed different levels of content related to the maturity stages. For instance threonine and isoleucine diminished in relation to age, suggesting that younger samples are better source for these amino acids. For the histidine, leucine and lysine content, the data revealed an increase associated with older ages. Finally the major content of amino acids corresponds to phenylalanine, threonine and isoleucine for all age groups.

Nopal also has potential for the treatment of diabetes due to its fibre content. The prickly pads can be a rich source of soluble fibre during younger ages and show increased insoluble fibre content at older ages. Crude fibre showed a positive relationship related to the age of the plant, however, the soluble dietary fibre tended to have negative relationship, suggesting than older nopal is better source of insoluble fibre (Feugang et al 2006)

Nopal powders can be an economic alternative when used as a dietary supplement in all seasons, without the need for fresh nopal. The dried products represent certain advantages for transport and preservation for prolonged periods in optimal conditions to ensure maximum nutritional quality and availability. (Hernández-Urbiola et al 2011)

The findings of Hernández-Urbiola (et al 2011)suggest that the nopal powders might be a good complement to other vegetables, meat and dairy products included in daily diets due to their essential amino acids content

Opuntia ficus-indica

Mexicans typically rat the nopal in its younger stages.

Edible (as opposed to medicinal) herbs (quelites) (although many of these plants serve both culinary and medicinal purposes).

Over the last five centuries, the diversity of species consumed as quelites has decreased by 55–90%. 15 species of quelites are currently consumed in the valley of Mexico, compared to 84 to 150 that were consumed in 1580. It is estimated that about 7, 000 species of plants are used in some way, whether for their medicinal, edible, or ornamental properties. (look at the excellent and comprehensive works of Edelmira Linares and Robert Bye if you want to research quelites to any great extent)

Quelites : Quelites : Quilitl

- Aceitilla – Bidens pilosa : Aceitilla : Bidens pilosa

- Alache – Anoda cristata : Quelite : Alache : Anoda cristata

- Anis herbs

o Anis de Chucho : Tagetes micrantha : Quelite : Anis de Chucho : Tagetes micrantha

o Anís de campo : Tagetes filifolia : Quelite : Anís de campo : Tagetes filifolia

o Huacatay : Tagetes minuta : Quelite : Huacatay : Tagetes minuta

o Pericón : Tagetes lucida : Quelite : Pericón : Tagetes lucida - Berros – Watercress – Nasturtium officinale

- Chaya – Cnidoscolus chayamansa : Chaya

- Chepil, chipil or chipilín – Crotalaria species : Quelite : Chipilin : Crotalaria longirostrata

- Chivatitos – Calandrinia species : Quelite : Chivatitos

- Epazote – Teloxys/Chenopodium/Dysphania species : Quelite : Epazote

- Flor de Calabaza – Squash Blossom : a little more info on both guías and flor de calabaza can be found here Quelite : Chepiche/Pipicha : Porophyllum tagetoides

- Guías de Calabaza – Squash Vines

- Hoja de Calabaza – Squash Leaves

- Hoja Santa (Acuyo) – Piper Sanctum

- Huauzontle – Chenopodium berlandieri nuttalliae : Quelite : Huauzontle

- Lengua de vaca : Quelite : Lengua de vaca

- Mafafa – Xanthosoma robustum : Quelite : Mafafa and Quelite : Mafafa : Eating the Taro stem

- Mexixquilitl – also called lentijilla – Lepidium virginicum : Quelite : Mexixquilitl

- Porophyllum species

o Hierba de venado (Deer weed) : A Note on Deer Weed : The Danger of Common Names

o Pápalo o Papaloquelite – Porophyllum macrocephalum – Broad leaved species : Quelite : Pápaloquelite : Porophyllum macrocephalum

o Pipitza/Chepiche – Porophyllum species – Narrow leaved species : Quelite : Chepiche/Pipicha : Porophyllum tagetoides

o Quillquina – Porophyllum ruderale : Quelite : Quillquina : Porophyllum ruderale

o Tlapanche : Quelite : Tlapanche - Piojito – Galinsoga parviflora : Quelite : Piojito : Galinsoga parviflora

- Quelite cenizo o quelite verde – Chenopodium album : Chenopodiums

- Quintonil. Amaranthus species : Nutritional Profile of Amaranth

- Romeritos – Suaeda torreyana : Quelites : Romeritos

- Tequelite – Peperomia species : Quelite : Tequelite

- Verdolagas – Purslane – Portulaca oleracea : Quelite : Verdolagas : Purslane

- Xocoyoli – Begonia species : See Xocoyoli : The Sour Quelite

Spirulina

Spirulina is the dried biomass of cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) that can be consumed by humans and animals. The three species are Arthrospira platensis, A. fusiformis, and A. maxima.

Spirulina was a food source for the Aztecs and other Mesoamericans until the 16th century; the harvest from Lake Texcoco in Mexico and subsequent sale as cakes were described by one of Cortés’s soldiers. The Aztecs called it tecuitlatl. (Habib etal 2008) (which roughly translates to rocks or stones excrement

Etymology: Nahua language. Simeon (1988) mentions that the suffix tetl means “stone” and cuitlatl “excrement”: excrement of stones. Karttunen (1992:73) speaks of te~tl, stone or gem; cuitlatl, excrement, excrescence, residue: “excrescence or residue of stones.” In relation to the names of towns such as Tlahuac, Cuitlahllac [or Cuitlahuatzin, Aztec king], Cuitlahuacan and Tecuitlatongo, Ortega (1972) writes that they are all toponyms of the term “algae.” There seems to be doubt about the suffixes tetl and teotl; if the latter one is joined to other words, it acquires the meaning “sacred,” “marvellous,” “strange,” and “surprising.” Robelo (1941) wrote, “Their name for gold was costicteocuitla or yellow excrement of the gods,” and for silver, iztacteocuitlak or “white excrement of gods.” Robelo includes the name Tecuitlapan, teocui-tla-a-pan: teocuitla, gold; atl, water and river; pan, in “The river of gold.” If the termination teotl was thought to be tetl, the meaning of tecuitlatl is completely different; it might mean “sacred excrement” and this could lead us to surmise that the ancient Mexicans considered this product to be a valuable mineral, just as did Hernandez (1959).

Motolina in 1541 (Benavente 1903) states: “On the water of the Mexican lake grows a kind of powdered slime, and at certain times of the year, when it becomes thicker, the lndians fish it out of the waler with very fine nets until their canoes are full of it; then the slime is put over sand to dry. They then prepare a sort of cake, thick as a finger. Afterwards it is cut in pieces like thick bricks and the Indians eat much of it and enjoy it. It is sold by many vendors in markets. It tastes like salt.”

Spirulina is quite nutritious and NASA has even looked at growing it in space as a foodstuff for astronauts. This algae represents an important staple diet in humans and has been used as a source of protein and vitamin supplement in humans without any significant side-effects. Apart from the high (up to 70%) content of protein, it also contains vitamins, especially B12 and provitamin A (β-carotenes), and minerals, especially iron. It is also rich in phenolic acids, tocopherols and γ-linolenic acid. Spirulina lacks cellulose cell walls and therefore it can be easily digested (Karkos etal 2011)

Spirulina can also be utilised medicinally

It has been demonstrated that….supplements can help lower levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides significantly (Huang etal 2018) , Another study notes spirulina can be an effective natural option for improving blood lipid profiles, preventing inflammation and oxidative stress, and protecting against cardiovascular disease (Ku etal 2013). Spirulina fights cardiovascular disease by lowering harmful LDL cholesterol levels while promoting healthy HDL cholesterol levels (Mazokopakis etal 2014) and can help encourage “significant reductions in body fat percentage and waist circumference (Serban etal 2016); it can help enhance muscle strength, endurance and performance (Kalafati etal 2010); it has been shown to help counteract anaemia with supplements found to increase the haemoglobin content of red blood cells, specifically benefitting older women (Selmi etal 2011). In the prevention and management of diabetes spirulina has shown to significantly lowered people’s fasting blood glucose level (Huang etal 2018) and supplementation is also linked to protection against allergic reactions, as it can help stop the release of histamines, which cause allergy symptoms. (Cemail Cingi etal 2008). These are only a few examples of studies performed on this “superfood)

Edible flowers

- Acocoxochitl – Dahlia species (edible tubers)

- Cacaloxóchitl – Raven flower – Plumeria (Frangipani) species

- Flor de Calabaza – Squash Blossom

- Izote – Yucca species

- Gualumbo – Agave species : Flor de Maguey : The Agave Flower

- Colorin (Mapuche) – Erythrinia species : Las Flores Comestibles : Edible Flowers : Colorin

According to the data, the best known edible flower in Mexico is the squash blossom (98 %), closely followed by the Mexican marigold (81 %). About a half of the Mexican population seems to know agave flowers (52 %), but the rest of the endemic edible flowers are known by 40 % of the respondents or less. (Mulik et al 2024)

This is a similar situation with the quelites. Of the potentially thousands (definitely many hundreds anyway) of the quelites available and eaten during the time of the Azteca many are now forgotten (or their use is only known in very regional areas) and now only exist as weeds of the milpa. This represents a huge loss of cultural knowledge.

Some are eaten as fruits, some are eaten as a vegetable, some are used as flavouring agents and many have medicinal use (check out the works of Mulik – see References – for some excellent work on this subject.

I have gone into individual flowers in various Posts (see links noted earlier) but they do deserve more work. There is a lifetime of study to be had on this subject.

….and many many more……

(Find some recipes here…..https://www.inpi.gob.mx/gobmx-2023/Libro-La-cocina-de-las-flores-INPI.pdf)

Here’s an interesting one to start with.

I have posted on this flower before so I won’t go into much detail here (just check out Cuetlaxochitl : The Poinsettia for more info – particularly medicinal uses). Here I’m just going to share some nutritional information

Crema de flor de nochebuena

Ingredients

- 1 cup dried poinsettia leaves-petals

- 250 ml milk

- 250 ml chicken broth

- 2 tablespoons chopped onion

- 2 tablespoons chopped parsley

- 2 tablespoons butter

- 1 tablespoon cornstarch dissolved in water

- Salt and nutmeg powder to taste

Method

- Melt the butter in a pan and fry the poinsettia leaves-petals, onion and parsley until the onion is browned.

- Add the chicken broth, cornstarch and milk, put on medium heat and

let it boil for two minutes. - Add salt and nutmeg to taste and let it cook for 2 to 3 more minutes.

The Dahlia

An important flower (so important it’s the national Flower of Mexico) is the Dahlia. I have posted on this plant before (find this at Acocoxochitl : The Dahlia)

Dahlia flowers

Dahlia root.

The root is not particularly high in calories but it does contain ample quantities of an insoluble fibre called inulin.

Inulin is a type of soluble fibre with prebiotic activities which regulates the intestinal microbiota by stimulating the growth of beneficial bacteria. This can also exert effects on the gut-brain axis and inulin may be beneficial in reducing depression. Inulin can also be used in treatments for obesity and diabetes. It can help regulate lipid metabolism and reduce blood sugars (1). Inulin is mildly laxative (it is a soluble fibre after all) so can help with constipation (and also reduces the risk of colon cancer). It can inhibit inflammatory factors (which can be important in diabetes) and nutritionally it enhances mineral absorption in the GIT.

- WARNING – DO NOT USE (without expert supervision) if taking diabetic medication (or any other medications that might lower blood sugar)

Varieties of dahlia roots

Fungi :

- hongos

- huitlacoche – (cuitlacoche) a plant disease caused by the pathogenic fungus Mycosarcoma maydis. One of several cereal crop pathogens called smut. In most corn growing regions it is considered a disease of corn crops and is destroyed. In Mexico it is considered a delicacy to be savoured.

Spices :

- pimienta gorda (allspice),

- achiote (annatto)

- hojas de aguacate – a variety of avocado leaf used (in a manner similar to bay leaves) for its anise flavour

- vainilla – the fermented pod of the vanilla orchid

Not a lot of spices originate from Mexico. Mexico has however rabidly adopted European and Asian spices and herbs. I would say cinnamon (or maybe cumin) is the most widely used adopted spice and cilantro/coriander the most widely adopted herb.

You are likely familiar with all of the above (except maybe achiote and hojas de aguacate). Achiote (or annatto) is typically not used as a spice (from a Western point of view) but it is widely used as a red food colouring. One variety of hojas de aguacate (avocado leaves) can be used in a manner similar to laurel (Bay leaves) albeit with an anise scent/flavour. Only 1 variety of avocado can produce these leaves. Although I would dearly love to, I have yet to cook with them.

Annatto food colouring

In general, annatto appears to be safe for most people. Though it is uncommon, some people may experience an allergic reaction to it, especially if they have known allergies to plants in the Bixaceae family. Symptoms include itchiness, swelling, low blood pressure, hives, and stomach pain. Seek medical advice if you encounter any of these symptoms.

Nuts

- Malabar chestnuts : Pachira aquatica (from southern Mexico to South America) also called Guiana Chestnut

- Pecan : Carya illinoinensis (southern United States and northern Mexico)

- Many species of Acorns – seeds of the genus Quercus Oak

- piñon nut : Pinus edulis (New Mexico)

Cacao (neither bean nor nut)

I won’t go into too much detail on cacao except to say that it originated in the Americas. It was a valuable foodstuff that the average person may not have been able to easily access (unless they lived and worked in the areas that produced it) (1). It does not grow in the mountainous area of Mexico City and which was the hub of the Aztec empire. It was at the time so valuable that the beans could be used as money. It has both nutritional and medicinal benefits.

- Cocoa is produced primarily by the state of Tabasco, which produces 66% of the national production, followed by Chiapas which produces 33%, both contributing to 99% of total production, the rest is produced between Oaxaca, Guerrero and Veracruz

Oils

- Aguacate (Avocado),

- pumpkin seed (1)

- although these oils were not produced in commercial quantities as we see them today

Yucatecans make a pumpkin seed “dip” called sikil pak. Cooks with “the touch” are able to coax a bright green oil from the seeds when making the dish. This is a skill.

Sweeteners

- Miel de maguey (Maguey honey) – produced by reducing down aguamiel (literally water – honey) which is the sap of the agave/maguey. When the plant reaches the point of flowering the flowerspike (quiote) is removed (a process called castration) and from the wound left behind a thin, sweet sap flows (as much as 4 or more litres per day). This sweet liquid can be drunk as is, reduced down by boiling into a honey like syrup or fermented for several days to created an alcoholic beverage called pulque (octli) with an alcohol content comparable to that of beer.

- miel de abeja melipona (from the stingless melipona bee). A Melipona hive produces one and a half liters of honey per year, and due to its limited production and medicinal properties it is highly appreciated. They are essential pollinators, since their pollen has a protein value 50 percent higher than that of other bees.

- produced from the aguamiel or sap produced by the castration (removal of the flowering spike (quiote) of several species of agave. This sap was also fermented to produce the alcoholic liquid called pulque.

A melipona bee hive

There is a long history of using this honey as medicine. Locals people already use the honey and wax from their hives to treat upper respiratory infections, skin conditions, gastrointestinal problems, and even to treat diabetes and cancer. Multiple studies suggest that honey from stinging and stingless bees has antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and wound-healing properties. (Cabezas-Mera et al 2024) (Esa et al 2022) (Rao et al 2016) (Zulkifli et al 2022) (these are only a small sample of the studies I looked at)

Although research does provide support for some of these uses, much of it is still preliminary. More research on the medicinal benefits of honeys is urgently needed.

Alcoholic drinks

The consumption (or rather the over consumption) of alcoholic drinks was frowned upon in Mexica society. Repeated infractions of drunkenness in public could potentially lead the drinker to be executed. This was not the case amongst all mesoamericans though. The Huasteca of the Gulf Coast (think Veracruz) did not share the same moral rigidity and were known for there outrageous drunken antics (as well as sexual exploits). Or maybe that’s just filthy Aztec propaganda.

Great. Now I’ve started a fight (although the Azteca didn’t need much encouragement to punch on)

Some of the alcoholic drinks available pre-hispanically (and still today – although you may need to search for them)

- Balché (see Pitarilla below)

- Chicha from various regions: obtained from corn stalks, when the cob is milky. It is also made from palms and pineapples.

- Chilatole from Puebla and Tlaxcala: corn reduced and fermented with chili and salt.

- Chilocle : From the Nahuatl chilli , chile, and octli (pulque). In Guerrero it is usually a mixture of pulque, ancho chile, epazote, salt and garlic. Pulque can be substituted with tuba, tepache or any intoxicating drink. It is known in Guerrero as chilote.

- Chanuco from various places: a type of cider made from fermented fruits with piloncillo.

- Chumiate from Mexico and Puebla: made from capulin and other fruits by infusion, maceration and straining.

- Colonche : fermented from the sour variety of nopal fruits called xoconoxtle. See Frutos de Cactus : Colonche

- Guásimo from Tabasco: a fermented juice from small pineapples.

- Menjengue from Querétaro: a drink made with pulque, corn, banana and piloncillo.

- Pitarrilla a Mayan drink from Chiapas and Yucatán : made from the bark of the balché tree dried in the sun and fermented with honey and water.

- Pulque – fermented aguamiel : See Pulque

- Sangre de Baca from Guerrero: fermentation of wild uvillas.

- Sende : Sendecho – (Zendecho) A fermented corn drink primarily of the Mazahua and Otomi peoples (made from either red or blue/black corn) often with guajillo chile blended into the mix.

- Tepache : from the Nahuatl word tepiātl which signifies that the drink was originally made from corn’. Now it is made from fermentation of very ripe pineapple skin.

- Tesgüino from Chihuahua, Jalisco and Nayarit: a type of beer made from malted corn/maiz

- Tuba from Colima and Guerrero: juice from the trunk of the coconut palm, easy to ferment.

Other drinks

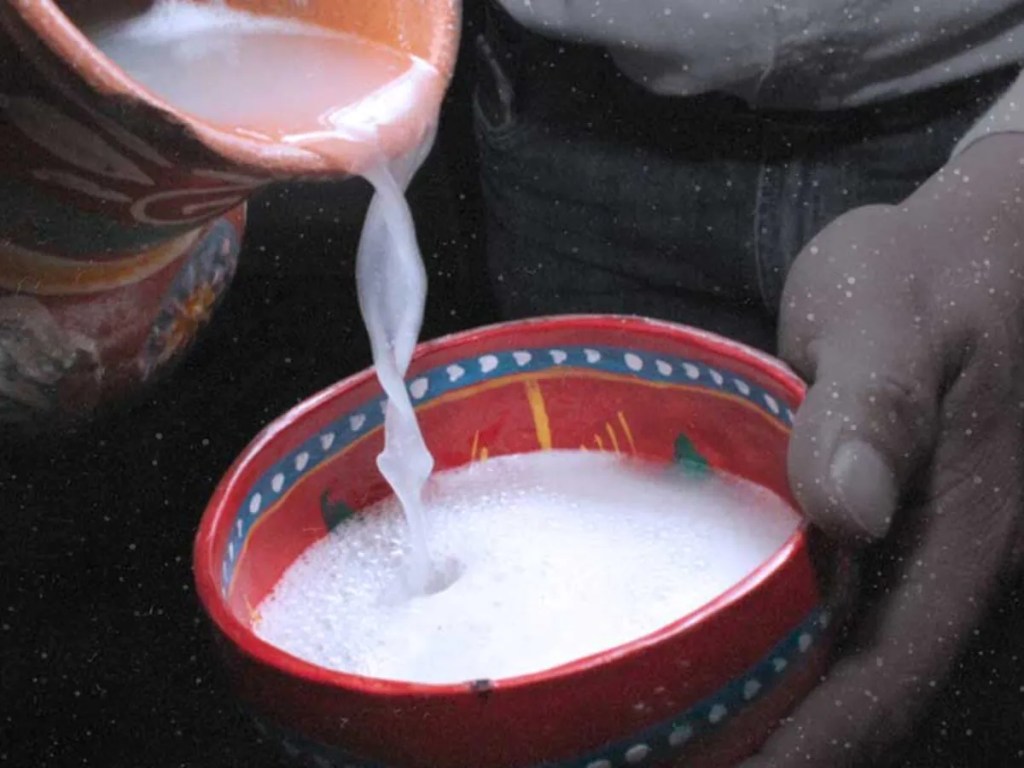

- Agua de barranca : a traditional cold and frothy drink made from cocoa beans, maize and beans (using broad beans – Vica faba – the fab/haba bean – distinguishes this Tlaxcaltecan product from other drinks made with cocoa or maize)

- Atole – made from nixtamalised corn masa. It is generall a snmooth liquid (although not always so, see Atole; Atole de Grano) and it can range in viscosity from watery to thick as gruel

- Buppu (Bupu meaning foam in Zapotec) : traditional drink of the Zapotecs of the city of Juchitán de Zaragoza in Oaxaca. It is prepared from white atole , cocoa and guie’ chachi flower, known locally as flor de mayo or Cacalosúchil (also known as plumeria or frangipani)

- Champurrado – a chocolate based atole made from cacao and nixtamalised corn dough (masa)

- Aguamiel – the fresh sap of the maguey (agave)

- Xocóatl – (xocolatl) chocolate – this was quite different to chocolate as we know it today. It was a thin water based drink that was bitter in flavour

- pozol – made from fermented corn masa and chocolate.

- Prehispanic Drinks – Bate – made from toasted and ground chan (a type of chia seed)

- Tejate – another type of cold chocolate based drink (from Oaxaca) flavoured and scented with flowers. It was (and still is) processed in such a way that the oils in the cacao are transformed into a thick white foam that floats on the surface of the drink. This is a highly skilled process.

For more information on Mesoamerican chocolate drinks see A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Diet : Appendix 1

Salt

The Nahuatl name of “Ixtapan” was given to various settlements which carried out activities related to the production of salt. Ixtapan means “the place where there is salt,” coming from the Nahuatl iztatl, which translates as salt. Hence words relating to salt come from the root iztatl. For example sea salt was called iztaxalli, the salt beds or places where salt was produced were called iztachihualoyan or iztaquixtiloyan, while specialists in salt production were given the title of iztachiuhqui or iztatlacatl. Salt sellers were known as iztanamacac, who traded loaves of salt called iztayaualli, which was ground up as iztapinolli or made into a solution as brine called iztayotl.

There was high consumption of salt in pre-Hispanic times, since it was used not just as a condiment, but also for preservation. It also featured as an ingredient in treatments for gum abscesses, molar pain, ear canal complaints, sore throats and coughs. Mixed with agave, it was applied to wounds to speed up healing. Salt and other salt products such as saltpeter and tequesquite were used to fix textile colors and for treating skin cuts.

Andrews (1980) notes that salt in Prehispanic Mesoamerica was a vital dietary requirement. In the modern world, most people fulfill their dietary salt requirements from animal protein, such as cattle, pork, and their derivatives, for example milk and fat. This was not possible in Mexico prior to Columbus and Cortés as these did not exist in the mesoamerican diet so the salt needs of the indigenous population had to be fulfilled by adding sodium chloride to the food. He also does some math for us noting the requirement of salt for peoples (particularly the Maya) in the tropical climates of the Americas. “People who live in these conditions usually require a minimum of 8–10 g of salt a day. The need for a few grams of salt a day may not seem like a big problem. However, let’s imagine a city of some 50,000 people in the tropics, most of them farmers or construction workers. It would take at least 400 kg of salt a day, or 146 tons a year, to sustain the society” and he notes that “when the supply (of salt) is interrupted it can have serious consequences.” Muñoz Camargo (1972) notes that the Tlaxcallans became accustomed to eating without salt after being besieged by the Aztecs for more than 70 years. The Aztecs maintained an almost perpetual state of war with Tlaxcala (but never actually conquered it) and although the salt lakes of Alchichica lay not far from Tlaxcala they could not benefit from this element in their diet (it didn’t make them any less formidable though).

Tequesquite

Tequesquite (1) is a natural mineral salt containing compounds of sodium chlorate, sodium carbonate, and sodium sulphate, used in Mexico since pre-Hispanic times mainly as a food seasoning. It is found naturally in central Mexico particularly in previously lacustrine (1) environments where the mineral salt forms a sedimentary crust. Its appearance is similar to that of common table salt in coarseness, but with a more greyish colour.

- See Tequesquite and Esquites, Tequesquite and a Witches Curse. for more information

- relating to or associated with lakes, which is relevant as much of the Basin of Mexico was covered by lakes

Tequesquite has many uses as an ingredient in traditional Mexican dishes. Mainly used in products made from corn, such as tamales, to accentuate their flavour (and in the case of tamales as a leavening agent which gives the tamal a “spongey” texture). It is also used for cooking nopales and other vegetables (as it helps retains their bright green colour), to soften dried beans or as a meat tenderizer, in a manner similar to how you might use sodium bicarbonate.

It also has medicinal uses. Aside from its use as an alkalizing agent in cooking, helping to balance the pH levels of acidic ingredients it can also be used to promote digestive health. Its alkalising effects can be used to treat various digestive issues and could potentially be used to alkalise urine in cases of urinary tract infections. In la Sierra Norte de Puebla a pedazo (piece) of tequesquite is added to an infusion of Piper sancti-felicis (a relative of Hoja Santa – Piper auritum) to treat empacho (1).

- A digestive illness that has no real equivalent in modern allopathic medicine. The symptoms are all relevantly the same but the causes of the illness and the treatments for it are not. See Empacho

So, what does this all boil down to?

The average diet of the Mexican (though not called this at the time) was largely meat free and was widely varied. Many of the fruits/herbs/flower/vegetables (as well as the insects and novel meat sources) were also medicinally utilised. A diet of this type would greatly benefit mankind.

From the point of view of a yerbero and naturopath this diet ticks all the boxes.

References

- Alatorre-Cruz, Julia María, Ricardo Carreño-López, Graciela Catalina Alatorre-Cruz, Leslie Janiret Paredes-Esquivel, Yair Olovaldo Santiago-Saenz, and Adriana Nieva-Vázquez. 2023. “Traditional Mexican Food: Phenolic Content and Public Health Relationship” Foods 12, no. 6: 1233. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12061233

- Amrouche, T. A., Yang, X., Capanoglu, E., Huang, W., Chen, Q., Wu, L., Zhu, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, Y., & Lu, B. (2022). Contribution of edible flowers to the Mediterranean diet: Phytonutrients, bioactivity evaluation and applications. Food Frontiers, 3, 592–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/fft2.142

- Andrews, A. P. (1980). Salt-Making, Merchants and Markets:the Role of a Critical Resource in the Development of Maya Civilization. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson.

- Banjo, A.D.; Lawal, O.A.; Owolana, O.A.; Olubanjo, O.A.; Ashidi, J.S.; Dedeke, G.A.; Soewu, D.A.; Owa, D.A.; Sobowale, O.A. An ethno-zoological survey of insects and their allies among the remos (Ogun State) South Western Nigeria. IAJIKS 2009, 2, 104–111.

- BENAVENTE, TORIBIO DE (also known as Motolinia). 1903. Memoriales. Mexico.

- BERGMANN, JOHN F. “The Distribution of Cacao Cultivation in Pre-Columbian America.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 59, no. 1, Routledge, Mar. 1969, pp. 85–96. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1969.tb00659.x.

- Bye, R. (2009). QUELITES-ETHNOECOLOGY OF EDIBLE GREENS PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE.

- Cabezas-Mera, F., Cedeño-Pinargote, A. C., Tejera, E., Álvarez-Suarez, J. M., & Machado, A. (2024). Antimicrobial activity of stingless bee honey (Tribe: Meliponini) on clinical and foodborne pathogens: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Frontiers, 5, 964–993. https://doi.org/10.1002/fft2.386

- Castillo, Ana María; Alavez, Valeria; Castro-Porras, Lilia; Martínez, Yuriana; Cerritos, René (2020). Analysis of the Current Agricultural Production System, Environmental, and Health Indicators: Necessary the Rediscovering of the Pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican Diet?. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, doi:10.3389/fsufs.2020.00005

- Carmona Rosales, Julio, “Sacred Herbs and Ancient Healers: Decolonizing Traditional Mexican Medicinal Practices” (2021). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 4635. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/4635

- Cemal Cingi, C. Conk-Dalay, M. Cengiz Bal, H. The effects of spirulina on allergic rhinitis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008 Oct;265(10):1219-23.

- Costa-Neto, E.M.; Ramos-Elorduy, J. Los insectos comestibles de Brasil: Etnicidade, diversidade e importância en la alimentación. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Aragonesa 2006, 38, 423–442.

- Cunha, Nair, Vanda Andrade, Paula Ruivo, and Paula Pinto. 2023. “Effects of Insect Consumption on Human Health: A Systematic Review of Human Studies” Nutrients 15, no. 14: 3076. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143076

- Esa NEF, Ansari MNM, Razak SIA, Ismail NI, Jusoh N, Zawawi NA, Jamaludin MI, Sagadevan S, Nayan NHM. A Review on Recent Progress of Stingless Bee Honey and Its Hydrogel-Based Compound for Wound Care Management. Molecules. 2022 May 11;27(10):3080. doi: 10.3390/molecules27103080. PMID: 35630557; PMCID: PMC9145090.

- FARRAR, W. Tecuitlatl; A Glimpse of Aztec Food Technology. Nature 211, 341–342 (1966). https://doi.org/10.1038/211341a0

- Figueredo-Urbina, Carmen & Álvarez-Ríos, Gonzalo & Zárraga, Laura. (2021). Edible flowers commercialized in local markets of Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo, Mexico. Botanical Sciences. 1. 10.17129/botsci.2831.

- Feugang JM, Konarski P, Zou D, Stintzing FC, Zou C. Nutritional and medicinal use of cactus pear (Opuntia spp.) cladodes and fruits. Front. Biosc. 2006;11:2574–2589. doi: 10.2741/1992

- Galindo, María & Arzate-Fernández, Amaury & Ogata, Nisao & Landero-Torres, Ivonne. (2007). The Avocado (Persea Americana, Lauraceae) Crop in Mesoamerica: 10,000 Years of History. Harvard Papers in Botany. 12. 325-334.

- Gifford-Gonzalez, D. (1999). Man Corn: Cannibalism and Violence in the Prehistoric Southwest. Christy G. Turner , Jacqueline A. Turner. Journal of Anthropological Research, 55(4), 607–608. doi:10.1086/jar.55.4.3631627

- Gilcrease, K. 2014. El conejo mexicano de monte (Sylvilagus cunicularius): Una perspectiva histórica de sucaza y del pastoreo, e implicaciones para planes de conservación. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n.s.), 30(1): 32-40

- Gómez-Álvarez, G. & Reyes-Gómez, S.R. & Teutil-Solano, C. & Valadez, Raúl. (2005). La medicina tradicional prehispánica, vertebrados terrestres y productos medicinales de tres mercados del valles de México. Etnobiología. 5. 86-98.

- Habib, M. Ahsan B.; Parvin, Mashuda; Huntington, Tim C.; Hasan, Mohammad R. (2008). “A Review on Culture, Production and Use of Spirulina as Food dor Humans and Feeds for Domestic Animals and Fish” (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Harvey HR. Public health in Aztec society. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1981 Mar;57(2):157-65. PMID: 7011458; PMCID: PMC1805201.

- HERNANDEZ, FRANCISCO. 1959. Historia Natural de la Nueva Espana. Pp. 408-410 in Obras Completas, tomo Ill, German Somolinos d’Ardois (editor). Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico, D.F.

- Hernández-Urbiola MI, Pérez-Torrero E, Rodríguez-García ME. Chemical analysis of nutritional content of prickly pads (Opuntia ficus indica) at varied ages in an organic harvest. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011 May;8(5):1287-95. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8051287. Epub 2011 Apr 26. PMID: 21655119; PMCID: PMC3108109.

- Huang H, Liao D, Pu R, Cui Y. Quantifying the effects of spirulina supplementation on plasma lipid and glucose concentrations, body weight, and blood pressure. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2018;11:729-742.

- Hunn, Eugene S. (2023) The Aztec Fascination with Birds: Deciphering 16th-Century Sources in Náhuatl : ISBN 10: 0999075985 ISBN 13: 9780999075982

- Isaac, Barry L. “AZTEC CANNIBALISM: Nahua versus Spanish and Mestizo Accounts in the Valley of Mexico.” Ancient Mesoamerica 16, no. 1 (2005): 1–10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26309390.

- Kalafati M, Jamurtas AZ, Nikolaidis MG, et al. Ergogenic and antioxidant effects of spirulina supplementation in humans. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(1):142-151.

- Karkos PD, Leong SC, Karkos CD, Sivaji N, Assimakopoulos DA. Spirulina in clinical practice: evidence-based human applications. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:531053. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen058. Epub 2010 Oct 19. PMID: 18955364; PMCID: PMC3136577.

- KARTTUNEN, FRANCES. 1992. An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman

- Ku CS, Yang Y, Park Y, Lee J. Health benefits of blue-green algae: prevention of cardiovascular disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Med Food. 2013;16(2):103-111.

- León-Ramírez, C.G., et al. (2014) Ustilago maydis, a Delicacy of the Aztec Cuisine and a Model for Research. Natural Resources, 5, 256-267. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/nr.2014.56024

- Linares Mazari, Edelmira & Bye Boettler, Robert (2015) Las especies subutilizadas de la milpa; Revista Digital Universitaria 1 de mayo de 2015 | Vol. 16 | Núm. 5 | ISSN 1607 – 6079

- Lisboa, Hugo M., Amanda Nascimento, Amélia Arruda, Ana Sarinho, Janaina Lima, Leonardo Batista, Maria Fátima Dantas, and Rogério Andrade. 2024. “Unlocking the Potential of Insect-Based Proteins: Sustainable Solutions for Global Food Security and Nutrition” Foods 13, no. 12: 1846. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13121846

- Mazokopakis EE, Starakis IK, Papadomanolaki MG, Mavroeidi NG, Ganotakis ES. The hypolipidaemic effects of Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) supplementation in a Cretan population: a prospective study. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2014;94(3):432-437.

- Mateos-Maces L, Chávez-Servia JL, Vera-Guzmán AM, Aquino-Bolaños EN, Alba-Jiménez JE, Villagómez-González BB. Edible Leafy Plants from Mexico as Sources of Antioxidant Compounds, and Their Nutritional, Nutraceutical and Antimicrobial Potential: A Review. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020 Jun 20;9(6):541. doi: 10.3390/antiox9060541. PMID: 32575671; PMCID: PMC7346153.

- Molina-Castillo, Stefany & Espinoza-Ortega, Angélica & Thomé-Ortiz, Humberto & Moctezuma, Sergio. (2022). Gastronomic diversity of wild edible mushrooms in the Mexican cuisine. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science. 31. 100652. 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2022.100652.

- Montes Osorio LR, Gil Esturban EA, Castillo Mont JJ, Sorensen M. The Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) – The Rediscovered Meso-American Functional Food Crop. Preprints.org; 2021. DOI: 10.20944/preprints202105.0128.v1.

- Morán, Elizabeth (2016). Sacred consumption: food and ritual in Aztec art and culture. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Mt.Pleasant, Jane; (2016) Food Yields and Nutrient Analyses of the Three Sisters: A Haudenosaunee Cropping System : Ethnobiology Letters 2016 7(1):87–98 | DOI 10.14237/ebl.7.1.2016.721

- Mulík, S., Hernández-Carrión, M., Pacheco-Pantoja, S.E., & Ozuna, C. (2024). Endemic edible flowers in the Mexican diet: Understanding people’s knowledge, consumption, and experience. Future Foods.

- Mulík, S., & Ozuna, C. (2020). Mexican edible flowers: cultural background, traditional culinary uses, and potential health benefits. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 100235. doi:10.1016/j.ijgfs.2020.100235

- Muñoz Camargo, D. (1972 [1892]). Historia de Tlaxcala. Biblioteca de facsímiles mexicanos 6, Guadalajara.

- Nowakowski, A.C.; Miller, A.C.; Miller, M.E.; Xiao, H.; Wu, X. Potential health benefits of edible insects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3499–3508

- Ordoñez-Araque, R.; Ruales, J.; Vargas-Jentzsch, P.; Ramos-Guerrero, L.; Romero-Bastidas, M.; Montalvo-Puente, C.; Serrano-Ayala, S. Pre-Hispanic Periods and Diet Analysis of the Inhabitants of the Quito Plateau (Ecuador): A Review. Heritage 2022, 5, 3446–3462. https:// doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040177

- Parsons, Jeffrey R. (2005) The Aquatic Component of Aztec Subsistence: Hunters, Fishers, and Collectors in an Urbanized Society : Subsistence and Sustenance vol. 15, no. 1, 2005 : https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?cc=mdia;c=mdia;c=mdiaarchive;idno=0522508.0015.104;rgn=main;view=text;xc=1;g=mdiag

- Perez-Fajardo, Mayra & Bean, Scott & Bhadriraju, Subramanyam & Perez-Mendoza, Joel & Dogan, Hulya. (2023). Use of Insect Protein Powder as a Sustainable Alternative to Complement Animal and Plant-Based Protein Contents in Human and Animal Food. 10.1021/bk-2023-1449.ch003.

- Perry L, Flannery KV. Precolumbian use of chili peppers in the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jul 17;104(29):11905-9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704936104. Epub 2007 Jul 9. PMID: 17620613; PMCID: PMC1924538.

- Pilcher, J. (2016, March 03). Taste, Smell, and Flavor in Mexico. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. Retrieved 18 Sep. 2023, from https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-260.

- Porcasi, Judith F. (2012). PRE-HISPANIC-TO-COLONIAL DIETARY TRANSITIONS AT ETZATLAN, JALISCO, MEXICO. Ancient Mesoamerica, 23, pp 251-267 doi:10.1017/S0956536112000181

- Qin YQ, Wang LY, Yang XY, Xu YJ, Fan G, Fan YG, Ren JN, An Q, Li X. Inulin: properties and health benefits. Food Funct. 2023 Apr 3;14(7):2948-2968. doi: 10.1039/d2fo01096h. PMID: 36876591.

- Rao, P. V., Krishnan, K. T., Salleh, N., & Gan, S. H. (2016). Biological and therapeutic effects of honey produced by honey bees and stingless bees: a comparative review. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 26(5), 657–664. doi:10.1016/j.bjp.2016.01.012

- Renard, Marie-Christine and Thomé Ortiz, Humberto (2016) “Cultural heritage and food identity: The pre-Hispanic salt of Zapotitlán Salinas, Mexico”. Culture & History Digital Journal, 5 (1): e004. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/chdj.2016.004

- Rivera Dommarco, Juan Ángel (CISP),Tania G Sánchez Pimienta (Conacyt-CINyS), Armando García Guerra (CINyS),Marco Antonio Ávila (CIEE), Lucia Cuevas Nasu (CIEE), Simón Barquera (CINyS),Teresa Shamah Levy (CIEE). : Situación nutricional de la población en México durante los últimos 120 años : Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública Av. Universidad 655, col. Santa María Ahuacatitlán 62100 Cuernavaca, Morelos, México

- ROBELO, CECILIO A. 1941. Diccionario de Aztequismos o sea Jardin de las Raices Aztecas. Palabras del Idioma Nahuatl, Azteca 0 Mexicano, Introducidas al ldioma Castellano bajo Diversas Formas. Third edition, Ediciones Fuente Cultural, Mexico, D.F

- Roos, N.; Huis, A. Consuming insects: Are there health benefits? J. Insects as Food Feed 2017, 3, 225–229.

- Sales Queiroz, Lucas & Nogueira Silva, Naaman & Jessen, Flemming & Mohammadifar, mohammad amin & Stephani, Rodrigo & Carvalho, Antonio & Perrone, Ítalo & Casanova, Federico. (2023). Edible insect as an alternative protein source: a review on the chemistry and functionalities of proteins under different processing methods. Heliyon. 9. e14831. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14831.

- Santley, R. S. (2004). Prehistoric Salt Production at El Salado, Veracruz, Mexico. Latin American Antiquity, 15(02), 199–221. doi:10.2307/4141554

- Seijo, G., Lavia, G. I., Fernandez, A., Krapovickas, A., Ducasse, D. A., Bertioli, D. J., & Moscone, E. A. (2007). Genomic relationships between the cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea, Leguminosae) and its close relatives revealed by double GISH. American Journal of Botany, 94(12), 1963–1971. doi:10.3732/ajb.94.12.1963

- Selmi C, Leung PS, Fischer L, et al. The effects of Spirulina on anemia and immune function in senior citizens. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8(3):248-254.

- Serban MC, Sahebkar A, Dragan S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of Spirulina supplementation on plasma lipid concentrations. Clin Nutr. 2016;35(4):842-851.

- Sidorova YS, Petrov NA, Perova IB, Kolobanov AI, Zorin SN. Physical and Chemical Characterization and Bioavailability Evaluation In Vivo of Amaranth Protein Concentrate. Foods. 2023 Apr 21;12(8):1728. doi: 10.3390/foods12081728. PMID: 37107523; PMCID: PMC10137383.

- SIMEON, REMI. 1988. Diccionario de la Lengua Nahuatl o Mexicana. Seventh edition. Siglo Veintiuno Editores, Mexico,D.F

- Stanislav Mulík, César Ozuna, (2020) Mexican edible flowers: Cultural background, traditional culinary uses, and potential health benefits : International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, Volume 21, 2020, 100235, ISSN 1878-450X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2020.100235.(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1878450X20301128)\

- Stintzing FC, Carle R. Cactus stems (Opuntia spp.): A review on their chemistry, technology, and uses. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005;49:175–194. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200400071.

- Valerino-Perea S, Lara-Castor L, Armstrong MEG, Papadaki A. Definition of the Traditional Mexican Diet and Its Role in Health: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2019 Nov 17;11(11):2803. doi: 10.3390/nu11112803. PMID: 31744179; PMCID: PMC6893605.

- Williams, E. (2021). SALT-MAKING IN MESOAMERICA: PRODUCTION SITES AND TOOL ASSEMBLAGES. Ancient Mesoamerica, 1–23. doi:10.1017/s0956536121000031

- Wong, Kaufui. (2017). Amaranth Grain and Greens for Health Benefit. Nutrition & Food Science International Journal. 2. 10.19080/NFSIJ.2017.02.555584.

- Zhang X, Shi J, Fu Y, Zhang T, Jiang L, Sui X. Structural, nutritional, and functional properties of amaranth protein and its application in the food industry: A review. Sust Food Prot. 2023; 1(1): 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/sfp2.1002

- Zulkifli NA, Hassan Z, Mustafa MZ, Azman WNW, Hadie SNH, Ghani N, Mat Zin AA. The potential neuroprotective effects of stingless bee honey. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023 Feb 8;14:1048028. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.1048028. PMID: 36846103; PMCID: PMC9945235.

Websites

- Diversity of quelites consumed : https://www.mexicanist.com/l/quelite-plants/

- La Dieta de la Milpa : https://www.gob.mx/salud/acciones-y-programas/la-dieta-de-la-milpa-298617

- Jornadas De Investigación Sobre Tamales Y Atoles (Research Conferences On Tamales And Atoles) : https://www.gaceta.unam.mx/tag/jornadas-de-investigacion-sobre-tamales-y-atoles/

- Pozole corn (hominy) – https://us.kiwilimon.com/tips/kitchen/basic-cooking/how-to-cook-pozole-corn

- Traditional Mexican Food Has Health Benefits : https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/992596?ecd=wnl_tp10_daily_230601_MSCPEDIT_etid5486128&uac=253652MN&impID=5486128#vp_1

- Xoloitzcuintle pozole – https://www.lajornadamaya.mx/nacional/203041/pozole-de-xoloitzcuintle-conoce-aqui-el-verdadero-animal-de-la-receta#

Fresh fish for Moctezuma

- https://www.strava.com/clubs/pescado-de-moctezuma-563466?hl=en-GB

- https://www.seafood-harvest.com/index.php/2020/12/04/the-birth-of-mexican-seafood/

- https://www.vivodeporte.com.mx/te-interesa/mensajeros-corredores-painanis/

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/giant-hill-smack-dab-middle-mexico-state-capital-xalapa-vondruska

Images

- Achiote – https://sowexotic.com/products/annato-achiote

- Agave cooked penca – https://specialtyproduce.com/produce/Parrys_Agave_Mescal_4479.php

- Agave cooked quiote – https://gentenayarit.com/2020/01/19/el-quiote-de-xalisco-nayarit-un-delicioso-remedio/

- Agua de barranca – https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2913524068712231&id=160660127331986&set=a.618789731519021&locale=sv_SE

- Aguamiel – https://medium.com/@natek205/exploring-zacatecas-mexico-sipping-on-the-traditional-elixir-aguamiel-3e12e9a7a001

- Aguamiel in the plant – https://www.elsoldesanluis.com.mx/circulos/que-es-el-aguamiel-10075842.html

- Aguamiel (pulque) – https://masdemx.com/2016/04/delicioso-pulque-sus-propiedades-medicinales-nutricionales/

- Amaranth seed – https://www.theseedcollection.com.au/grain-amaranth-golden

- Bupu – https://fundaciontortilla.org/Emprendimientos/el_bupu_de_esperanza_una_bebida_tradicional_istmena

- Cacao pods – https://www.fromasmallseed.co.uk/her-story/

- Cacao pulp – https://myexoticfruit.com/shop/#!/products/cacao-fruit

- Cacao beans – https://naturespath.com/blogs/posts/the-health-benefits-of-cacao

- Cactus fruit – garambullo – https://hscactus.org/resources/plants-of-the-month/myrtillocactus-geometrizans-february-2020/

- Cactus fruit – tuna – https://www.facebook.com/cactusfruitsaustralia/photos/pb.100063808680388.-2207520000/2971544879836866/?type=3

- Cactus fruit – xoconostle – https://www.researchgate.net/figure/External-and-internal-features-of-xoconostle-fruit-The-edible-part-of-xoconostle-is-the_fig1_273913593

- Chia seed – https://www.amazon.in/Chia-Seeds-Sowing-Cultivation-Enthusiasts/dp/B0D96FTVQ1

- Chile varieties – dried – https://www.mexicoinmykitchen.com/mexican-dried-peppers/

- Chile varieties – fresh – file:///C:/Users/SimonO’Connor/OneDrive%20-%20Rener%20Health%20Products/Desktop/Foodwise_pepper_guide-1024×683.webp

- Chiloctli – https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=3986650728037728&id=197875093581996&set=a.202640393105466

- Cuauhocuilines – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1018567061670981&set=a.232098580317837&locale=ta_IN

- Cupiches – https://www.directoalpaladar.com.mx/ingredientes-y-alimentos/comida-insectos-como-tendencia-que-como-se-come-que-podemos-esperar

- Depiction of harvest of spirulina and the cakes made from the algae. Illustration from the Florentine Codex, Late 16th century. – Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2158186

- Dried beans – https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1301022393413781&id=478527342329961&set=a.478529598996402&locale=es_LA

- Fresh beans (pole) – https://catalog.parkseed.com/park-seed-2023-big-seed-spring-book/page/50-51

- Fresh beans (bush) – https://catalog.parkseed.com/park-seed-2023-big-seed-spring-book/page/50-51

- Garambullo fruit – via Metztitlán “Lugar de la Luna” on Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=4028735637218822&set=a.693326247426461

- Guaje tree – https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/2092174

- Harvesting spirulina – Hamed, Imen. (2016). The Evolution and Versatility of Microalgal Biotechnology: A Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 15. 10.1111/1541-4337.12227.

- Husk tomatoes – tomate verde – https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=QLGSfVz2LJ8

- Huitlacoche – https://fundaciontortilla.org/Cocina/huitlacoche_entre_quesadillas_moles_y_atoles

- Huitlacoche en la mercado – https://www.sinembargo.mx/21-07-2017/3265307

- Jumiles – https://mexico.knowledgize.com/en/d/traditional-mexican-food/knowledge/insects/jumiles

- Nopales at the mercado – https://www.animalgourmet.com/2017/12/05/nopal-fundamental-siglo-xxi/

- Nopales cooking on the comal – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdYnj6ug_zE

- Nopal farming – https://www.gaceta.udg.mx/mostraran-bondades-del-nopal-el-alimento-del-futuro/

- Pimienta gorda – https://mayoreo.online/products/pimienta-gorda-entera

- Potato varieties – common – file:///C:/Users/SimonO’Connor/OneDrive%20-%20Rener%20Health%20Products/Desktop/a-cool-guide-to-western-australia-potato-species-v0-aoxzcn9rr88b1.webp

- Potato varieties – unusual – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=10159045024789700&set=a.138830229699

- Quinoa seed – https://au.pinterest.com/pin/planting-and-growing-guide-for-quinoa-chenopodium-quinoa–227431849924523207/

- Selection of wild mushrooms in Mexico – https://www.tomzap.com/feriaarticle1photos.html

- Tejate – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=259977346115201&set=pb.100069955268382.-2207520000&locale=gl_ES

- Tejuino – https://gourmetdemexico.com.mx/viajes/guadalajara-alimentos-bebidas-y-leyendas/attachment/tejuino/

- Tsats (Zats) – https://www.instagram.com/llenatedechiapas/p/C8xiNBHNxTR/?img_index=1

- Vainilla orchid – https://www.etsy.com/listing/1263926612/vanilla-planifolia-vanilla-orchid-20-to

- Vainilla pod green – https://en.norohy.com/once-upon-a-time-there-was-vanilla/

- Vainilla pod dried – https://www.etsy.com/listing/732228915/gousses-de-vanille-grand-cru-de

- Varieties of maiz – https://www.ceplas.eu/en/discover/planters-punch/how-to-follow-corn-genes-into-the-past

- Varieties of summer squash – https://www.kqed.org/bayareabites/134043/zucchini-and-beyond-a-farmers-market-guide-to-summer-squash

- Varieties of tomato – https://www.reddit.com/r/interestingasfuck/comments/vm7egc/all_varieties_of_tomato_on_one_table/#lightbox

- Varieties of winter squash – https://www.thekitchn.com/the-11-varieties-of-winter-squash-you-need-to-know-ingredient-intelligence-157857

- Yucca/Yuca – (image) https://nativeamericanmuseum.org/4-march-2024-yucca-or-yuca/