I briefly look at the masa based drink called atole in my Post Mexican Cooking Equipment : The Molinillo but lets go into it in a bit more detail here and in another related Post I’ll investigate a range of chocolate beverages based on this ingredient called masa.

Atole (Spanish) from atolli (Nahuatl) which, according to the definition, is a beverage made from finely ground maize, mixed with water.

“a gruel made of maize, which they call atolli . . . agreeable, harmless, and provides a pleasant and healthy food . . . for those suffering from a hot, dry fever; it calms the chest, is very nutritious, strengthens and fattens the emaciated, and restores lost strength.” (1)

- The Mexican Treasury: The Writings of Dr. Francisco Hernández, ed. Simon Varey, transl. Rafael Chabrán, Cynthia L. Chamberlin, and Simon Varey (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000)

Most atole is made by diluting nixtamalised corn masa dough in water, flavouring and sweetening it and then cooking it so that it thickens. It can be thickened to ones personal preference – some like it thinner (almost watery) and some like it thicker (almost gruel like). Other ingredients such as blended fruits, chocolate, nuts, amaranth or even pumpkin are added to atole to sweeten it, boost its flavour and add to its nutritional profile. Not all atole is sweet. Some such as Atole de Grano and chileatole are savoury.

Before I wander too far I’d like to look at gruel. ¿Qué es?

This word keeps coming up in descriptions of atole so let’s check it out.

Gruel is a food consisting of some type of cereal—such as ground oats, wheat, rye, or rice—heated or boiled in water or milk. It is a thinner version of porridge that may be more often drunk rather than eaten. Historically, gruel has been a staple of the Western diet, especially for peasants. Gruel may also be made from millet, hemp, barley, or, in hard times, from chestnut flour or even the less bitter acorns of some oaks. Gruel has historically been associated with feeding the sick and recently-weaned children or as a foodstuff of the very poor.

It did however make it onto the menu of the Titanic (only in 3rd class though)

Now, back to the corn.

The first (and probably the original) ingredient used is that of fresh corn

Fresh corn atole

The Nahuas of northern Veracruz make sintliatolli (centilli is corn) (sic)(1).

- sintli – Alternative spelling of cintli, corn.

This atole is prepared in the northern Sierra of Puebla, when harvesting as an offering to give thanks to Mother Earth. It is eaten with tamales made from corn, sugar, bicarbonate or tequesquite and salt.

Ten tender ears of corn are sliced and ground in a metate or blender; the paste is put in a litre of boiling water, ground chili, sugar and salt to taste are added. Boil for 20 minutes. If it is too thick, add more water. It is enough for ten people. (Buenrostro & Barro 2000)

The next ingredient is that of masa. The ubiquitous Mexican “dough” made from freshly ground nixtamalised corn. Nixtamalisation is the process of cooking maiz kernels in an alkaline solution. This helps to remove the hard coating of the kernel and fundamentally changes the nutritional and physical structure of the corn itself (1). Masa can also be dried out to form masa flour (or masa harina) which can be readily reconstituted back into a dough with the addition of nothing more than water. This dough can be used to make tortillas (or any of the Vitamina T foodstuffs)(2)(3)(4)(5) as well as atole (although purists will say it is by far inferior to fresh masa).

- For more information on this see Nixtamal

- Masa, Tortillas and Vitamin T

- Ingredient : Asiento and a Brief History of Tlayudas, Doraditos and Huaraches.

- Vitamina T : Totopos and the Chilaquil

- Vitamina T : The Tlapique. Cousin of the Tamal.

This dough can now be used to produce a dizzying array of foods from the humble tortilla to the more complicated tamal and a thousand things in between (1).

Today however we look at atole.

Atole at its most basic is masa, diluted in water and then heated to thicken the liquid. It can be thickened to ones preference, ranging in texture from almost watery/soup like through thicker textures like “custardy” and into “gruel” like. If you set it aside in the fridge overnight (and its already quite thick) it can become almost pudding like. Typically though it is drunk whilst still warm. Milk can be used to replace some of the water used which will add richness (and nutrition) to the drink and it can be flavoured with any number of spice, fruits, herbs, nuts/seeds/grains……the list goes on

To prepare a good atole, you need a good clay pot, which is preferably used only for this purpose. You also need a wooden spoon or stirrer, since preparing atole involves stirring constantly so that it does not burn or stick to the bottom of the pot.

It can be made in any kind of pot (I’d avoid aluminium though) but the clay pot will add a flavour profile that won’t be found if you use a stainless steel or glass pot.

Or, if you don’t have the time to wait around

Commercial varieties of “instant” atole

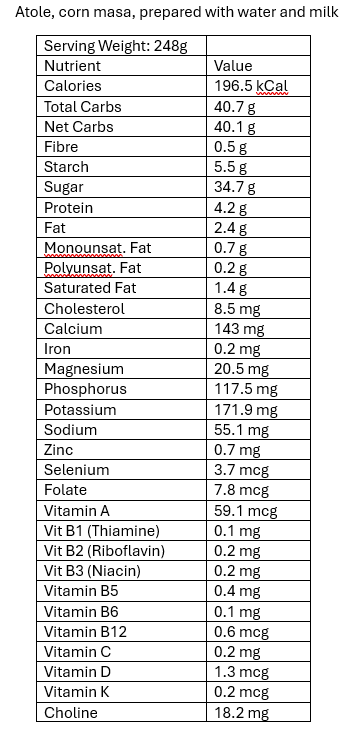

Atole is both nutritious and medicinal. It is readily digestible and offers a valuable foodstuff for for both pregnant women, young children and geriatric/elderly peoples.

The nutrition of atole has been studied.

Studies have shown that…..

- participants receiving Atole from conception to age 2 years showed improved child survival, improved growth, and offered strong protection against diabetes and that individuals exposed to atole between birth and age 24 months scored higher on intellectual tests of reading comprehension and cognitive functioning in adulthood than those not exposed to atole or who were exposed to it at other ages. (Prentice 2018)

- Nutritional supplementation (of atole) in girls is associated with substantial increases in their offsprings’ (more for sons) birth weight, height, head circumference, height-for-age z score, and weight-for-age z score. (Behrman etal 2009)

- Protein-energy supplementation (of atole) during the first 1000 d of life in Guatemala, where undernutrition is prevalent, reduced the prevalence of later mental distress in adulthood. (DiGirolamo etal 2022)

So it is definitely a positive nutritional addition to the diets of children and these same children have more beneficial outcomes to their own pregnancies and mental and intellectual health status once they become adults than those children that did not receive this intervention.

Other ingredients such as chocolate, flowers and even achiote (more on this later) will also boost the medicinal qualities of atole

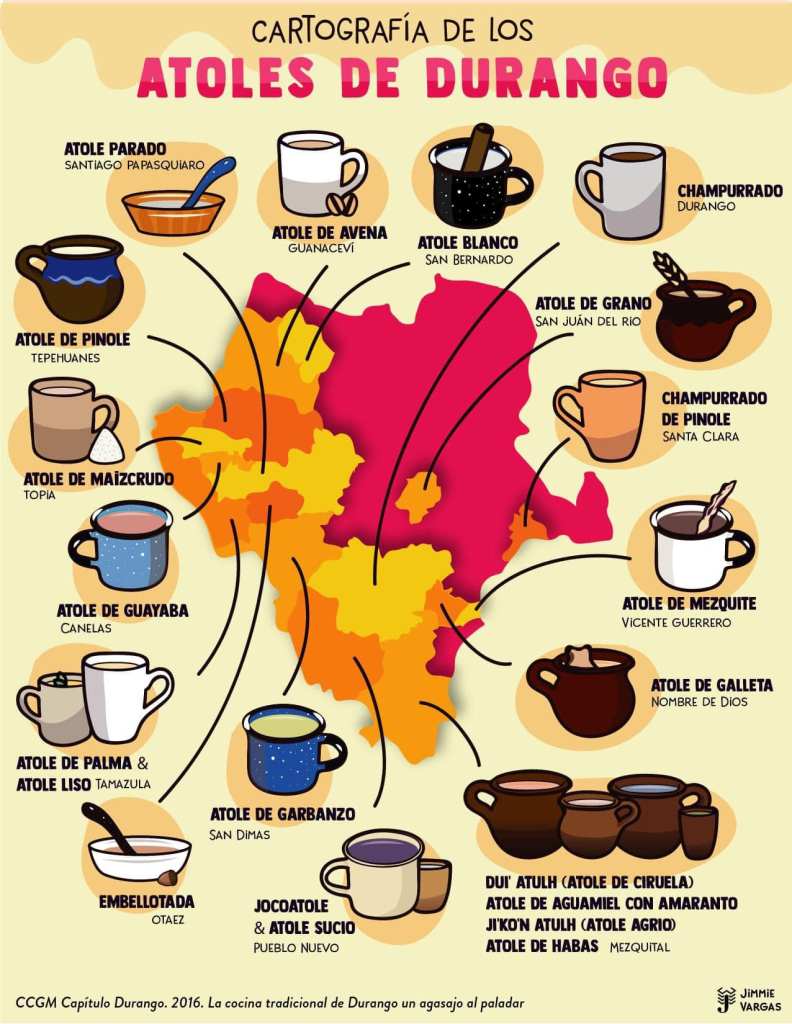

Atoles can be particular to certain regions….

……and may even have many varieties even within a single region…..

Francisco Hernández de Toledo (c. 1515 – 28 January 1587) was a naturalist and court physician to Philip II of Spain. In 1530 he began to study medicine at the University of Alcalá and received a bachelor’s degree in 1536 (Varey 2000). From 1556 to 1560 Hernández served as a physician at the Hospital y Monasterio de Guadalupe in Extremadura. In 1570, Hernández was ordered to embark on the first scientific mission in the New World, to compile a study of the region’s medicinal plants and animals.

Hernández describes over 3,000 Mexican plants, a feat that was significant because classical texts did not amass so much plant biodiversity. The first text of Hernández’s work, Index medicamentorum, was published in Mexico City. It is an index that lists Mexican plants according to therapeutic use and their traditional uses; the index was arranged according to body part, and it was ordered from head to toe. in the 16th century Hernández discovered that there were more types of medicinal atoles than he had the ability to record.

A short list of a few of the atoles that drew the attention of the proto-doctor (1) Felipe II, Francisco Hernández follows:

- “Proto-professionalism” is a term used to describe the period before a medical professional has acquired practical wisdom, or phronesis. Phronesis is a defining characteristic of a professional that is developed through experience and reflection. This experience occurs as the professional’s knowledge and skills grow.

The atole that Hernández (1) was most interested in is nequatolli or atolli with honey (necuhtli), made with corn, water, lime and maguey honey.

- (Hernández, Francisco, 1517-1587. : Historia de las plantas de Nueva España)

Nequatolli or atolli with “honey” : Atole de Aguamiel : Atole con Miel (aguamiel – not honey) (1)

- Nutritional Value of Aguamiel. Aguamiel is the key ingredient for the alcoholic mesoamerican drink Pulque. It can be made into a syrup (by slowly boiling it and evaporating some of the water present in the liquid) Agave Syrup. A Healthy Alternative to Sugar? and if you take the syrup a little further you get….miel de agave (agave honey) which, aside from being nutritious, has medicinal value….Medicinal use of Miel de Agave (agave honey).

I will begin with the nequatolli or atolli with honey, to which lime is added, so that there are eight parts of water, six of this Indian grain, and one of lime; everything is put in a clay vessel and over a low fire until it softens, then it is removed from the fire, covered with cloths, and finally ground on the stone called metlalt; it is then cooked in a clay vessel until it begins to condense or thicken, at which point a tenth part of metlat (1) honey is added, which has been discussed in its place, and finally it is left to boil for the time necessary for it to take the consistency of puches or Spanish polenta.

- “metl” is the Nahuatl word for the Agave. Maguey is more commonly used these days though

The Indians use this food at all hours of the day, whether they are healthy or sick, but mainly in the morning and accompanied by some drink.

An interesting fact is that the atole was “accompanied by some drink”; this last detail is significant in understanding that atole was not thought of as a drink, but as a food. Hernández attributes various health benefits to it and it could be consumed by sick and healthy people alike.

It refreshes and moistens those who suffer from hot and dry intemperance, soothes the chest, nourishes greatly, strengthens and fattens the exhausted and restores lost strength; it also cleanses the body and is a proper food for the sick. Even those who suffer from consumption are given barley tea instead, and it is a great help for those who rise from very serious illnesses.

So. An excellent food for those convalescing after (generally serious or debilitating) illness. (1)

- to recover one’s health and strength over a period of time after an illness or medical treatment. i.e. “he spent eight months convalescing after the stroke”

The Nahua word “necuhtli” (1) means honey (2), and early Mesoamericans had several types of it, including bee honey (miahua necuhtli), maguey nectar (menecuhtli) and aguamiel (iztac necuhtli). In addition, indigenous words used the root necuhtli, which generically designated honey and was linked to other words such as necutic, which meant “something sweet.”

- or nectar or unfermented juice

- also neuctli, necutli, necuctli

Hernández then goes on to list more atoles……

Nechillatolli, that is, atole mixed with chili and honey (necuhtli)

Atolli iztac or white atole. Iztac = white in Nahuatl

Xocoatolli or sour atole. (Xoco/xoxo usually indicate “sourness” when used in a word)

Atole Agrio : Sour Atole, also known as “Xocoatolli.” Made by first making a dough using black corn. The dough is allowed to stand 4 or 5 days, so it can ferment. The dough is then used to make atole, with the fermented maize lending it a sour flavour. It is further flavoured with salt and chile.

Once served, salt and chili are added, and the sick take it in the morning to cleanse the body, provoke urine and purge the abdomen. With the same ferment dissolved in cold water and taken, the body is refreshed when it is scorched by heat or tired from the journey or work, or when the kidneys are so irritated that the urine stings and ulcerates the urinary tract.

Yollatolli or white atole,

Atole Blanco : White Atole, also known as “Yollatolli.” The cornmeal is white, made from white corn.

White atolli – which the Mexicans call yollatolli – is made in the same way as the corn in the manner mentioned above, but without lime or any other substance. It is made into a pudding, allowed to cool, and diluted to be easily drunk, in the same way as the one we spoke of earlier. They say that it extinguishes thirst, whatever its cause, and that it prevents it, thus avoiding excessive drinking.

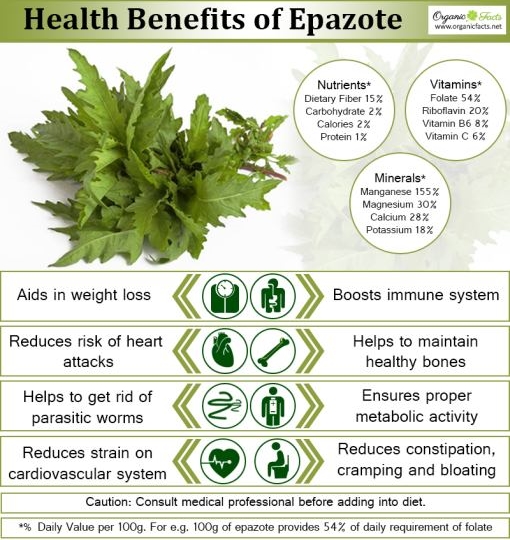

Atole de Ayocote : Also known as “Ayocomollatolli.” Chillatolli (see Atole con Chile below) to which cooked beans and epazote are added.

Another type called ayocomollatolli uses beans. Ayacotl is the Aztec name for bean.

“This one is made by adding chillatolli, epazotli, and the pieces of dough when it is all half cooked, and finally when it is nearly done, whole cooked beans. It constitutes a splendid and most pleasant food, and by virtue of the epazotli, it purges the blood and raw humors.”

Epazote is a typically Mexican herb. It is strongly flavoured and not to everyone’s liking. The flavour is unmistakeable and persists. I once ate a squash blossom quesadilla (containing flor de calabaza, quesillo and whole epazote leaves) first thing in the morning and every time I burped that day all I could taste was epazote.

Some of the health benefits in the infographic above seem a little vague but as a herbalist (in Western Herbal Medicine anyway) I know this herb as wormseed and it is a potent antiparasitic (of the GIT) treatment (1).

WARNING

Epazote is a potent and potentially poisonous medication. It is a low dose herb and is contraindicated in both pregnancy and breastfeeding. The essential oil of this plant is an outright poison and should only be used by professionals. The infographic above shows “Daily Values” for 100g of epazote. This is a ridiculous amount to consume (and I am only showing this infographic to demonstrate this). DO NOT EAT THIS MUCH FRESH EPAZOTE.

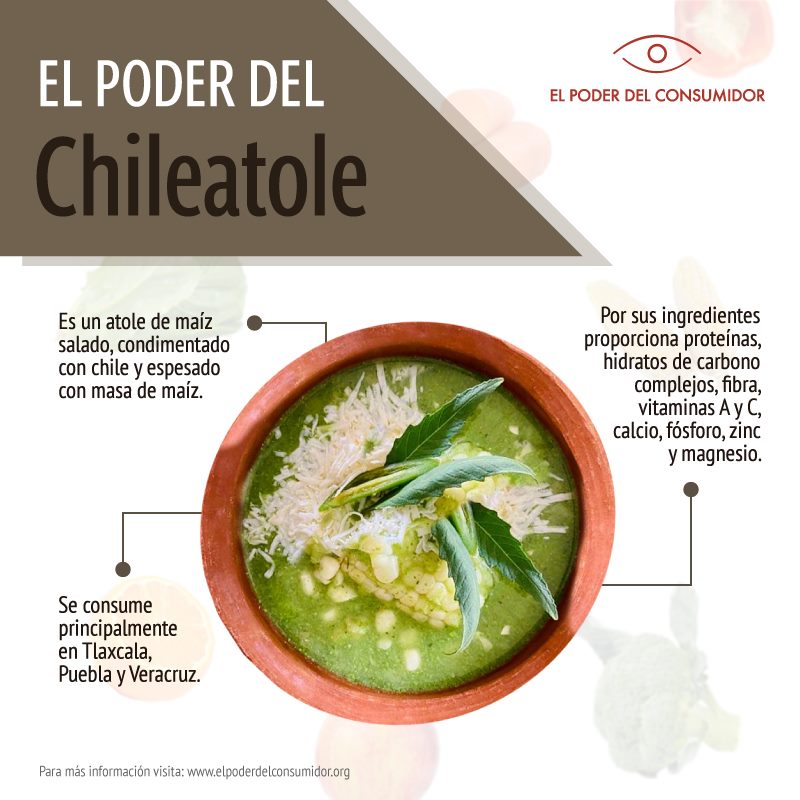

Chillatolli or atole mixed with chili (chileatole)

Atole con Chile : Also known as “Chillatolli”, “Atole with chile.” Before making standard Atole, a chile is steeped in the water for taste, or ground chile stirred into water.

It is taken in the morning against the discomforts of cold, tones the stomach, helps digestion, removes adherent phlegm and cleanses the intestines by evacuating all their impediments.

Traditional chileatole from the Mexican state of Tlaxcala is different from other, similar dishes, due to the addition of fine, young pumpkin and chayote leaves, growing in the same fields as the corn plants, as is typical for the Central-American cultivation system called milpa. In other parts of the country chileatole is prepared with the same corn base, but the addition of chicken, pork or typically, cheese.

Chinatolli or atole with chia,

Atole con Chía : Also known as “Chinatolli”, “Atole with sage.” Toasted, powdered sage is added. Ground chile may also be added.

Chiantzotzolatolli or atole made with a seed larger than chia seeds. See Prehispanic Drinks – Bate for more information on this seed.

Michuauhtolli – amaranth (amarantos) seed atole with michihoauhtli

Atole de amarantos

“And another drink is prepared which they call michihuauh atolli, which means atole that has michihuauhtli seeds, which was also treated in its place, which seed must be toasted and ground, and when necessary, it is added to be diluted in water, in such proportion that it does not thicken too much, and they pour a little maguey honey on top, and because there are three kinds of this honey, as will be said in its place, this drink cleanses the kidneys and the urinary tract, cures scabies in children through the virtue that it has, and is a very used food for the native Indians”.

Hoauhatolli – amaranth seed atole using red amaranth seed

Tlatonolatolli with dried chili powder and epazote;

Tlaxcalatolli

tlaxcalatolli, which is prepared from ground corn and made, in the comalli, into tortillas three fingers thick; when these are well cooked, the crust is removed, the crumb is crushed, mixed with cold water and put back on the fire, stirring it until it begins to thicken, it is taken out, served in glasses and taken with a spoon; it restores and increases strength admirably.

Olloatolli prepared with burnt corn and cobs : Atole de Olotes

Ollontolli (cob atole). From the Nahuatl word olotl . The central part of the corncob, from which the grains are removed. It is used as fuel, to make corn shellers and as animal feed.

Ollontolli – La espiga del maíz (olote) se quema y reduce a cenizas, se muele y se mezcla en proporción de una parte por tres de maíz

Even from the corn cob, already without grains, burned and reduced to ashes, it is customary to prepare the so-called ollontolli; it is ground, mixed in a proportion of one part to three parts of corn, ground everything together again and put on the fire until the atolli is well cooked and has the density of polenta; it is then served in glasses and chilcoztli is added. It is useful for those who have excess blood or heartburn.

Atole de Árbol : Also known as “Quauhnexatolli” (cuauhnexatolli), “tree Atole.” Made with tree ashes (sic.)

Also, from corn cooked in common lye, the so-called quauhnexatolli is made because it is made with tree ashes. The corn is left in the lye for the time necessary for it to soften; it is thus purified and acquires a special flavor very different from the others; It is then ground and cooked like the others until it has the proper density, and when taken in this way they say that it purifies the blood although it does not provide any other service as medicine or as food.

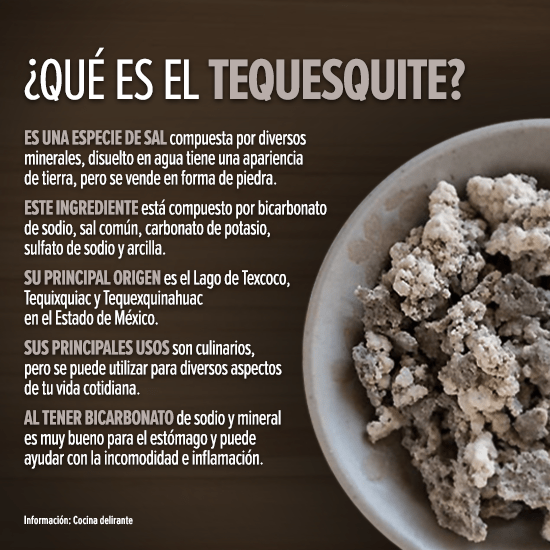

Graulich (1999) notes of cuauhnexatolli that it is an atole made with thick and very white masa mixed with tequixquitl (Tequesquite) and was important food offering during Huey Tozoztli. Hueytozoztli (or the “great vigil”) is the fourth month of the Aztec year and corresponds with the dates of April 13th-May 2nd in the Gregorian (our current) calendar. It is a festival in the Aztec religion dedicated to Centeotl, Chalchiuhtlicue, Xilonen, Chicomecoatl, and Tlaloc.

For more information on the nixtamalisation of maiz using wood ash (called cuanesle) see Nixtamal

Other varieties of atole include

- Atole de arroz : Rice atole – warm Horchata – essentially rice pudding in a warm drink

- Atole de avena : atole thickened with oatmeal (Avena sativa)

- Atole de beso de ángel : Angels kiss atole – flavoured with cherries, sometimes contains walnuts or pecans and thickened with cornflour or rice flour

- Atole de cacahuate : Peanut atole, with ground peanuts for flavouring.

- Atole de Fruta : Also known as atole with fruit. Usually made with cornstarch rather than with masa harina. The fruit is puréed first.

- Atole de garbanzo : atole made with toasted and cooked garbanzo beans (chickpeas)

- Atole de mezquite (mesquite) : atole made with milk, and flavoured with cinnamon, sugar and small pieces of cooked mesquite bark. Drunken mostly in Guanajuato, and even there rarely now.

- Atole de pechita : atole made using ripe mesquite pods

- Atole de piñones : Pine nut atole. With ground pine nuts for flavouring.

Aside from being a nutritionally valuable foodstuff for everyone from the very young to the very elderly atole is also a medicinal foodstuff. Some of theses use (although being somewhat archaic – although no less the relevant because of this) have been noted in the works of Dr. Francisco Hernández.

Traditional midwives note that it can also play a valuable role for the new mother as atole can aid in increasing milk production and uterine recovery in birthing peoples and so it is often a medicine offered to pregnant/birthing parents just after birth and throughout the first 40 days of postpartum healing (and beyond).

Bourke (1894) notes of this “To bring milk to the breasts of women, or to expand breasts not fully developed. – Drink twice daily an “atole,” or gruel, made out of powdered and toasted mulberry twigs.” It is also noted that “It is believed that it is important to be in good spirits while making this as if not it will curdle.”

A Pharmacy log book of the Royal Indian Hospital, 1721 (1) details a list of drugs as used at a hospital used to treat indigenous people in Mexico City. A significant portion of the medicines distributed are labelled as “atoles” (2). Some atoles were made of common medicinal plants, such as endive, mint, and almonds; others, however, remain quite unknown and are only listed as “golden atole” or “complete atole.”

- Hospital Real de Naturales, “Libro de botica en que se asientan las medicinas que se traen para este Hospital Real de los Naturales.” (Mexico, 1721), 3v-4r, Colección Antigua 0643, Archivo Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico.)

- atole de lombrises, violet atole, golden atole, atole of borax and pink honey, sweet almond atole, atole of sesame, atole completo, endive atole, mint atole, lily atole, atole rosado enfansino, caper atole, and bitter almond atole.

Hospital Real de Naturales, “Libro de botica en que se asientan las medicinas que se traen para este Hospital Real de los Naturales.” (Mexico, 1721), 3v-4r, Colección Antigua 0643, Archivo Histórico del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico

The atoles were distributed with careful attention to medical needs, “according to their sickness and the duration thereof,” and inclusion within the pharmacy logbook of the hospital makes it clear that the medical role of this foodstuff was recognized.

There many superstitions around the World in regards to food, cooking and the kitchen. Some of the “masa” based superstitions in Mexico include…..

- it is highly recommended not to cook tamales while you are angry. If you are the tamales won’t fluff up properly making them dense and unpleasant to eat (although being angry will make your salsas spicier)

- if the tortilla puffs up when you are cooking it then you are ready to get married, if it doesn’t you are bound to live with your parents forever (more on marriage in Atole de Novia below)

- dropping tortillas on the ground will conjure the arrival of one’s in-laws, showing up unannounced to pay you a particularly unfortunate visit

The book Como agua para chocolate (Like Water for Chocolate) narrates the story of the lovesick Tita. Throughout the book her cooking (and those who consume it) are affected by her moods and emotions.

Other superstitions specifically involving atole are……..

- if more than one person stirs the pot, it will taste bad.

- If a pregnant woman enters the room while a batch made from young corn is cooking, the drink will curdle.

- And if anyone in a bad mood touches it, the drink becomes bitter.

Maricruz, a Mexican cook and photographer living in Italy, shares these dichos populares (popular sayings) on her blog (https://www.maricruzavalos.com/)

- Más vale atole con risas que chocolate con lágrimas (atole with laughter is better than chocolate with tears): Although its flavour is delicious, previously the atole was considered a drink for the poor classes and chocolate was related to the upper classes, hence the saying, it can be interpreted as better to be happy even if you are poor, than to be rich but unhappy.

- No se puede chiflar y beber atole (you can not whistle and drink atole): It is better to do one thing at a time well, than two things done poorly.

- Si con atolito vamos sanando, pues atolito vámosle dando (if with atolito we are healing, then we keep on with the atolito): Probably its origin was related to the healing properties that are given to the atole in some regions. This saying can be interpreted as if a method is effective, it should be followed rather than trying a new one.

- Contigo la milpa es rancho y el atole champurrado (With you the corn field is as beautiful as the countryside and atole is sweetened with chocolate). Is a love expression about not matter how things go, with your beloved one at your side everything looks better.

- Dar atole con el dedo (give atole with a finger): It is one of the most common sayings, it means to deceive someone. Its origin has to do with giving “a little taste” – or palliative – to someone to calm them down.

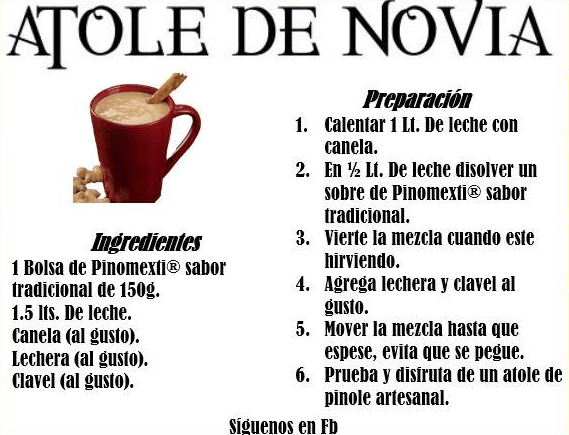

Atole de Novia

This version of atole is made with pinole or toasted maize (and in some places I have seen that the addition of pinole changes the name to Atole Velo de Novia – “Brides Veil Atole”). This particular variety is from Michoacán and was made by the newly wed bride for her in-laws the day after the wedding. It is said that if she failed to impress with the drink then she was returned to her home and the marriage was over. Talk about pressure.

Ingredients

- 1 ½ litres of water (1500ml)

- 2 pieces of piloncillo (approx. 500g – substitute 2 cups Brown sugar)

- 1 (5cm) cinnamon stick

- 100 grams of masa (preferably nixtamalized – substitute with masa harina)

- 2 chocolate tablets (I like the Abuelita brand)

- 1 cup of pinole (see below)

- 2 litres of milk

Method

- Put 1 litre of water, piloncillo and cinnamon in a pot (preferably made of clay); Cook over high heat until the piloncillo dissolves.

- Mix half a litre (500ml) of water with 100 grams of tortilla dough (masa), whisk until the dough dissolves completely.

- Strain the mixture through a sieve over the clay pot.

- Add chocolate tablets and pinole

- Mix and cook over high heat until the chocolate has melted.

- Add milk, cook over medium heat and stir constantly until thickened.

- Serve warm

How to Make Pinole

What you will need:

- Frying Pan – cast iron is preferred but non-stick is acceptable

- Dried corn on the cob

- Molcajete (or coffee grinder, blender, mortar and pestle)

Method

- Remove the dried out corn kernels from the cob.

- Heat frying pan over medium heat.

- Spread out all of the corn kernels on the hot frying pan in a single layer. You want all of the kernels to be touching the pan. Toast the kernels until they become swollen and are a light brown colour.

- Remove the toasted corn kernels from the frying pan and allow to cool. Grind until the corn is finer than cornmeal but not as fine as wheat flour (think masa harina)

You can also make Pinole by taking cornmeal or Masa Harina and carefully toasting it in a pan. The cornmeal may need some further grinding after toasting but the masa harina will not. Just be careful not to burn it. The mix can also be enriched by the addition of chia or hemp seeds.

Atole de aguamiel

Atole de aguamiel is produced using the fresh sap of the maguey. This sweet herbaceous liquid is collected from the agave plant from the wound created by “castrating” it when the flower spike called the quiote is removed (1). Typically the sap is then briefly fermented to create the alcoholic drink known as pulque (2) but in this case it is heated and thickened using masa to create an atole without using piloncillo sugar as a sweetener. The sap can also be reduced into a syrup by carefully boiling it to create a type of “honey” somewhat akin to the process of making maple syrup (3)

To make atole de aguamiel you’ll need…

- 2 litres of fresh aguamiel

- 250 grams of masa (of any coulour)

Method

- Place the aguamiel in a clay pot and bring it to a gentle boil

- Thin the masa with a little aguamiel and add it to the boiling aguamiel

- Stir constantly (so that the liquid does not stick to the pot and burn) until the liquid comes back to a boil and thickens

- Allow to cool a little before serving in clay mugs

It is said that this atole should be prepared in a clay pot and served in clay mugs as this gives it a special flavour

(Recipe from Arqueología Mexicana Edición Especial No.12 Cocina Prehispánica

Recetario (Edición Bilingue)

Atole agrio

Like another Mesoamerican fermented nutritional powerhouse, Pulque (1), atole also exists in a fermented form. Atole agrio (or sour atole) is made primarily from fermented corn.

- See also : Medicinal Qualities of Pulque

In many regions of the country, sour atole has several names that come from Nahuatl, for example xocoatole, jocoatole, xucoatole, shucoatole, atolshuco, atolxuco and others like it; all referring to the sour or acidic taste of the drink: the Nahuatl word xococ or xoxotl means “sour”.

The corn is processed through a process called nixtamalization (1) before being ground into a dough called masa which is a ubiquitous foodstuff in Mexico and is the dough responsible for that most quintessential Mexican food, the tortilla. As we have seen, this dough can be diluted to make atole but if you allow the dough to ferment you can then make a sour probiotic laden atole called “atole agrio”.

- Although there are recipes which use fresh corn.

The process of making sour atole requires time and patience. It may take between 36 – 48 hours from the start of nixtamalization, through the fermentation and then the making of the atole itself.

First nixtamalize your dried corn kernels. Typically white or yellow corn is used but regional variations might include the use of purple, red or black varieties of corn.

The process of nixtamalization involves cooking the corn in water and lime (1) (2 spoonfuls of lime for every litre of water), at a temperature of almost 80 ºC for 30 minutes, then left to stand for many hours. This is usually done at night and in the morning the liquid is drained and the corn rinsed many times until the rigid hull (pericarp) which covers each kernel is removed. Dispose of this alkaline cooking liquid (called Nejayote) carefully.

- Calcium hydroxide – or Cal – not the citrus fruit called a lime (or limón) in Mexico

Now the fermentation can take several paths

- Un-nixtamalised : Leave the corn kernels whole (i.e. don’t nixtamalise them and remove their skins), cover it with water and leave in a warm place for 1 or 2 (or maybe even 3 days) to ferment (or “sour”). The container should be shaken periodically to ensure uniform fermentation. Some recipes call for the liquid used to cover the corn to be strained off and heated to make the atole; others call for the treated corn to be ground into a masa and then the dough left to ferment for several more hours before being diluted in water, strained to remove any grit and then cooked to produce the atole. All recipes made with this corn (or the soaking water) are cooked with cinnamon/canela and piloncillo

- Grind the corn finely in a mill (or on a metate if you think you’ve got the strength of backbone for it). Make a thick slurry of this masa with clean water and set aside to ferment. This may take 1 or 2 days. Strain this masa slurry to remove any grit and then cook, in a clay pot, with cinnamon/canela and piloncillo, stirring constantly and adding enough liquid to reach the desired consistency. These atoles are usually on the “runnier” side of thickness.

Other ingredients, such as fruits, can be added in the final cooking step.

Fresh corn can also be used to make this drink. From Chiapas comes the following recipe

- 2 Kg. Tender yellow corn

- 500 gr. Sugar

- 2 slices Cinnamon slices

- 4 litres Water

Preparation

Soak the corn for 3 days, until it is sour.

On the fourth day, wash the corn and grind it finely.

Mix the dough with the water (1 of dough for 2 of water), beat until both ingredients are perfectly incorporated then let it stand 8 hours.

Strain the water from the dough with the help of a cloth, let it rest for an hour.

Pour the water from the dough into a pot, add sugar and cinnamon, when it starts to boil add the dough sediment, stir constantly. Let it boil until it thickens.

Tlilatolli (atole noir – black atole) from the Nahuatl………

tlilli. black color, black ink, black paint, soot; also, a person’s name (attested male)

or…….

tliltic. black, the color; or, a black person, a person of African heritage

and……..

atolli. a beverage made from finely ground maize, mixed with water, taken into Spanish as atole

Izquiatolli, with toasted corn

I have found reference to “a typical regional atole prepared for Dia de Muertos” in Veracruz

This atole is known as atole negro or in Nahuatl “izquiatol”, which is made from burnt corn. The way to prepare it consists of toasting the corn on a griddle until it burns (all the corn has to be black), then it is ground in a metate with the metlapil (stone roller with which it is ground in the metate) and then it is passed through a strainer to obtain a fine powder. Separately, the dough is mixed with water and brought to a boil in a pot with a cinnamon stick, chocolate powder and sugar, and it is stirred frequently so that it does not stick. Once it begins to boil, the fine powder of ground burnt corn is added and it is taken off the heat so that the burnt corn can be mixed in well and so that it does not burn or stick to the cooking pot.

Atole negro and other atoles made with wood ash

First, a warning. Nixtamalisation is the process whereby corn kernels are cooked in an alkaline solution so as to effect the removal of the hard outer skin (or pericarp) of the kernel so that it can be ground into a dough called masa. The alkalinity of the liquid also fundamentally changes the nature of the dough (through the creation of various colloids and gums) which also gives the masa a flexibility which it would not otherwise have (Santiago-Ramos etal 2018). It also makes nutrients in the corn bioavailable (1) when they would otherwise not be (2). Nixtamalisation is primarily done by creating an alkaline solution using “lime”, no, not the citrus fruit, but the chemical called lime or calcium hydroxide (often just called “Cal”). Nixtamalisation occurs between the pH of 8 to 12 with the optimum pH level being somewhere around 10.5 to 11. This is where the warning comes in. pH levels of 10 or above are damaging to the skin and levels of 12.5 or above are able to burn the skin. A pH of 14 (where the alkalinity level actually tops out) will cause serious burns in a very short time. So you need to be VERY careful when using Cal. Avoid breathing in the powder or getting it in your eyes. First aid for exposure to calcium hydroxide includes…In case of contact with your eyes, immediately flush eyes with plenty of water for at least 15 minutes. Cold water may be used. Get medical attention immediately. Skin Contact: In case of contact, immediately flush skin with plenty of water for at least 15 minutes while removing contaminated clothing and shoes. If the chemical was swallowed, immediately give the person water or milk, unless instructed otherwise by poison control or a provider. If the powder is inhaled – Remove person to fresh air, keep warm and quiet, give oxygen if breathing is difficult. Seek immediate medical attention.

- gives it the ability to be absorbed and used by the body

- particularly B vitamins. See Nixtamal for some information on the illness of nutritional deficiency called pellagra which can be caused by eating un-nixtamalised corn (as your primary grain)

This warning also includes the alkaline liquid (Cal mixed with water) called Nejayote that remains after the corn is nixtamalised. This liquid is a potential health danger (and also an environmental one….See my Post Nejayote for more on this). Now it’s taken me a while to reach my point as another way to alkalinise the nixtamalisation cooking liquid is to use wood ashes to create cuanesle (1). This liquid is just as alkaline (and just as dangerous) as using calcium hydroxide and creates a certain conundrum. How much wood ash is safe to use/eat? Some recipes for the following atoles simply have the corn alkalinised via cuanesle but the corn is washed well afterwards and made into atole without the further addition of ashes to the drink. This still creates an atole with a different flavour profile than one made from masa nixtamalised using Cal. Others in the family have wood (or other) ashes added to the drink which are then consumed by the imbiber. Consumption of ash can actually be beneficial (2) but it can also be potentially dangerous.

- see Nixtamal for more on this

- See Medicinal Ash.

In an interesting article by Christine Green on curanderismo I came upon a reference to using wood ash to fortify the nutritional value of and strengthen the medicinal value of atole…

Whenever Tonita Gonzales was sick, her grandma would bring her warm, soothing atole. This rich blue corn meal drink, often fortified with juniper ash, is a staple for many in the American Southwest and Mexico.

A recipe for atole de ceniza from Santa Catarina Palopo in Guatemala gives an indication of the amount of wood ash to be used

Ingredients

Dough – 10 lbs (a little over 4 1/2 kilograms or 4536 grams)

Ash – 2 ounces (56 grams)

Preparation

The dough is placed in a pot and water is added until it has a liquid consistency, then the ash is added.

Proceed to cook, stirring constantly until it acquires a thick consistency.

The recipe below is for conextli atole, originally from the Nahuas of the Zongolica region in Veracruz

Ingredients

- 1 piloncillo

- 2 litres of water

- 2 cinnamon sticks

- 200 grams of thinned masa

- Fire ash diluted in water

Method

- In a pot, bring the water to a boil and add the piloncillo and cinnamon.

- Once it boils and the brown sugar has dissolved, add the thinned masa and about 5 minutes later the ash diluted in water.

- Stir everything until the mixture thickens a bit.

- Serve and enjoy.

Atole Negro

also know as Atole Prieto or Atole de Chaqueta

Atole de chaqueta serves as the base for another drink called “chilate”, traditional from the Costa Chica of Guerrero, which is drunk cold. See A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Appendix 2 : Chocolate Drinks for a rundown on Chilate

An atole negro considered to be a traditional delicacy amongst the Purépecha of Michoacán

- 1 cup dried corn silk

- 50 grams of cocoa shell

- 1 star anise

- 200 grams of nixtamalized corn masa

- 1 piece of piloncillo (200 grams)

- 10 grams of cinnamon

- 2 litres of water

Method

- Dilute the dough in 1 litre of water.

- Heat the rest of the water with the diluted corn masa in a pot over low heat.

- Add the piloncillo and heat over low heat until the mixture begins to thicken.

- In a griddle or saucepan, toast the corn silk and cocoa shells until they are completely charred.

- Blend the anise, cinnamon, cocoa and corn silk with 1 cup of hot water.

- Strain the liquefied black liquid and add it to the atole.

- Heat for a few minutes until the atole thickens, cook for 3 minutes and turn off.

Tip: To intensify the colour, blend the rest of the strained cocoa and corn shells with a little of the prepared atole.

Atole de amarantos

Amaranth is a quelite (1) that can either be eaten as a green vegetable or for its highly nutritious seed (2) and can also be utilised for its medicinal properties (3).

Amaranthus cruentus is the variety known as huauhtli by the Aztecs and the name is still utilised by Nahuatl speaking peoples throughout Mexico to this day.

Michihuauhtli or “huauhtli de pescado” – Nahuatl for fish amaranth due to its superficial resemblance to fish roe (eggs) was the name of the variety commonly used to make tzoalli (1). Tzoalli played a large role in Aztec religious rites and practices and was frowned upon (and outlawed) by the Spanish (2).

- these days called alegria (happiness/joy) Recipe : Alegrias de Amaranto : Amaranth Joys.

- Amaranth and the Tzoalli Heresy

The seed (both whole, reventado/puffed and ground as a flour) can be used to make atole

Atole de alegria

Ingredients (For 10 to 12 people)

- 500 grams of toasted or untoasted amaranth seeds

- 250 grams of sugar

- 2 x 5cm cinnamon sticks

- 2 litres (8 cups) of water

Method

- If your amaranth seed is untoasted then lightly toast it in a dry pan (or on the comal) stirring constantly with a wooden spoon so that it does not burn and toasts evenly.

- Allow to cool and grind into a powder

- Dissolve the powder in a little cold water.

- Put the 2 litres of water in a pot and bring it to a boil.

- When it comes to the boil, add the dissolved amaranth, the cinnamon sticks and the sugar.

- Stir constantly to prevent it from rising.

- When it begins to boil, lower the heat and let it simmer for 10 to 15 minutes until it thickens.

- Serve in clay mugs with pan dulce (one recipe suggests it be accompanied with tamales de rajas)

Variations

Use milk instead of water to make the atole

Add some vanilla to the milk for flavour (1 Tablespoon per 2 litres – or to taste)

Use piloncillo instead of white sugar. Sugar can also be replaced with condensed milk. Use 1 can per 2 litres of milk.

Use popped/puffed amaranth seed instead of whole seed. Use ½ to 1 cup of puffed amaranth per 1 litre (4 cups) of milk. Lightly toast the puffed amaranth as in the recipe above before grinding it into a powder. Alternatively place the puffed seed (you can also use the whole seed here too) and 1 litre of cold milk into a blender and blend it well. Add this to the rest of the milk which has been warming in the pot with the cinnamon and sugar before bringing it to a boil, reducing the heat to a simmer, and then cooking it to the desired thickness

Use pre-prepared amaranth flour. 100g per litre of milk.

Chinatolli (Chia atole)

Ingredients:

- 1 litre of water or milk (according to your preference)

- 1 cup of chia

- 1 cinnamon stick or 1 teaspoon of ground cinnamon

- 1/2 cup sugar (adjust to taste)

- 50 grams of nixtamalized corn dough or corn flour

Method

- In a large pot, add the water or milk and the cinnamon stick. Bring to a boil.

- Meanwhile, dilute the nixtamalized corn dough or corn flour in a little cold water to avoid lumps, making sure to obtain a homogeneous mixture.

- Once the water or milk is boiling, add the corn masa mixture, stirring constantly to combine well and avoid lumps.

- Add the chia and sugar, mixing well. If you used ground cinnamon, now is the time to add it.

- Cook over medium-high heat, stirring constantly, until the atole reaches the desired consistency, approximately 10 to 15 minutes.

- Once the desired consistency is reached, remove the cinnamon stick if used and serve hot.

Notes

- You can sweeten the chia atole with honey, stevia or any other natural sweetener of your choice.

- For a more intense flavour, you can lightly toast the chia seeds before preparing the atole. Traditionally, this drink is made by roasting chia seeds on a griddle until golden brown, then grinding them into a fine powder. This powder is then added to water and mixed vigorously until the liquid reaches a drinkable consistency, and optionally, chili powder can be sprinkled on top.

- You can add fresh fruits, such as strawberries, bananas or blueberries, to the chia atole to give it an even more delicious and nutritious touch.

- Chia atole can be kept in the refrigerator for up to 3 days.

Atole de Jamaica

See Flor de Jamaica (Hibiscus sabdariffa) and Flor de Jamaica : A Confusion of Hibisci* for more information on this plant.

This atole can range in colour from almost brownish to deep port red or even strawberry coloured depending on how you dilute it with masa (or even the colour of the masa used – which can range from white, to yellow, to red and even to blue and almost black)

Ingredients

- 2 full cups dried flor de jamaica

- 1 large cinnamon stick

- 10 cups water (2 ½ litres)

- 1 1/2 cups Masienda red corn masa harina (or your favorite white or yellow masa harina or 500 grams of fresh nixtamalized corn masa – if you can get it)

- Piloncillo or regular granulated sugar, to taste

Method

- Place the hibiscus in a large strainer and rinse for 30 seconds under cold water. Transfer to a large pot. Pour in 7 cups (1750ml) of water. Add the cinnamon stick. Heat to medium. When it comes up to a boil, reduce the heat slightly and cook for 15 minutes.

- When ready, strain the hibiscus water to another pot (1). Heat to medium. Sweeten with piloncillo or granulated sugar, to your liking.

- Rehydrate the masa harina in 3 cups (750ml) of water and strain to avoid the formation of lumps.

- When the jamaica comes up to a light simmer, gradually stream in the blended masa harina while stirring the whole time. Continue stirring so the masa doesn’t stick to the bottom of the pot.

- Taste for sweetness. Remember that the hibiscus is naturally very tart, so add sugar to your liking.

Serve warm

- Use the cooked flowers to make Tacos de Jamaica : Flor de Jamaica : Tacos dorados con Crema de Aguacate

Atole de Pechita (Mesquite atole) (Hinton 1956)

This atole was observed being made in Tepupa village on the Moctezuma River east of Hermosillo.

- Gather ripe, sweet, and reddish purple bean pods from large mature mesquite trees

- Set aside in a cane basket or warm, well ventilated spot until the pods dry out thoroughly (as long as six weeks)

- Place the whole pods in a large container and cover with clean fresh water

- Soak overnight or until soft

- Pour the soaking water and the soft pods into a heavy wooden bowl (batea) and using a cucharon (a large wooden spoon) mash the pods well.

- Several times throughout the mashing process squeeze the stringy pods with your hands to extract the juice and pulp.

- The water should become thick and discoloured with the soft matter from the pods

- Wring out the pods one last time to remove as much as you can from them and then discard the stringy fibres and seeds that remain,

- Strain the remaining mixture of water, juice, and pulp, discarding any coarse material.

- Set aside 1 cup of the liquid and pour the remainder into a clay olla (pot)

- Cook until the liquid becomes syrupy

- Add panocha (piloncillo) to taste

- To the cupful of material set aside, add wheat flour (or cornflour) and mix until well integrated and smooth. The amount needed will depend on how thick you want your finished atole to be

- The contents of the cup are now added to the liquid cooking in the olla and the mixture and stir well and continuously until the atole thickens

- You can add cinnamon and ground cloves at this stage to give additional flavor.

- The resulting atole de pechita is usually drunk, and may be served as a thick broth or thin gruel that can be taken either hot or cold but locally it is usually preferred cold.

Alternatively…….

Atole de galletas Marias : Maria Cookie Atole

(5-6 servings)

Ingredients

- 6 cups milk

- 1 cinnamon stick

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 1/3 cup piloncillo

- 1 package of Maria cookies (200 grams),

Method

In a medium pot, bring the 4 cups of the milk to a simmer along with the cinnamon, vanilla, and sugar.

Meanwhile, place the chopped cookies in a blender along with 2 cups of milk. Blend until all the cookies are completely broken up and you have a smooth, homogeneous mixture. If you have trouble blending, you can add a little of the milk you have warming on the stove.

Pour the cookie mixture into the pot with the milk

Cook, stirring constantly, until it thickens. Remove the cinnamon stick. Serve immediately.

Serve the Maria cookies atole in individual cups to keep it warm.

Notes

- You can garnish with a little ground cinnamon or powdered Maria cookies.

- You can use any milk you like. Substitue 1 can of evaporated milk for 1 ½ cups of the regular milk

- Sweeten with white sugar if you like or omit it entirely and use a can of condensed milk (omit 1 cup of milk from the recipe if you do this)

We are drifting away from optimal health and nutrition with this recipe though

Remember tha bag of mas azul I asked you to ignore at the beginning? Well this is why. (If you weren’t already aware…..Azul = blue)

References

- Behrman JR, Calderon MC, Preston SH, Hoddinott J, Martorell R, Stein AD. Nutritional supplementation in girls influences the growth of their children: prospective study in Guatemala. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Nov;90(5):1372-9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27524. Epub 2009 Sep 30. PMID: 19793851; PMCID: PMC2762161

- Bourke, John G. (1894) Popular Medicine, Customs, and Superstitions of the Rio Grande : The Journal of American Folklore , Apr. – Jun., 1894, Vol. 7, No. 25 (Apr. – Jun.), pp. 119-146 : The American Folklore Society

- Brown, K.A. (2002). [Review of the book The Mexican Treasury: The Writings of Dr. Francisco Hernández, and: Searching for the Secrets of Nature: The Life and Works of Dr. Francisco Hernández]. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76(3), 597-599. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/bhm.2002.0115.

- Buenrostro, Marcos & Barro, Cristina (2000) ITACATE Martes 3 de Octubre de 2000 : Atoles y más atoles (Primera parte) : https://www.jornada.com.mx/2000/10/03/04an2cul.html

- Díaz-Ruiz, Gloria; Valderrama, Anita; Esquivel, Karina; Espinosa, Judith; Centurión, Dora; Reyes-Duarte, Dolores; & Wacher, Carmen. (2008) MICROBIAL POPULATIONS IN ATOLE AGRIO: A TRADITIONAL MEXICAN FERMENTED MAIZE BEVERAGE : Ciencia Básica de CONACYT CB2008-01 No. 101784. https://smbb.mx/congresos%20smbb/cancun13/TRABAJOS/SMBB-Simposia/Alimentos/DiazAtoleAgrio.pdf

- DiGirolamo AM, Varghese JS, Kroker-Lobos MF, Mazariegos M, Ramirez-Zea M, Martorell R, Stein AD. Protein-Energy Supplementation in Early-Life Decreases the Odds of Mental Distress in Later Adulthood in Guatemala. J Nutr. 2022 Apr;152(4):1159-1167. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxac005. Epub 2023 Feb 18. PMID: 36967173

- González Jácome, Alba (2017) Corn and Food: A brief history of a long journey : Revista de Geografía Agrícola núm. 60 / 9 : dx.doi.org/10.5154/r.rga.2017.59.007

- Graulich, Michel, and Instituto Nacional Indigenista (Mexico). 1999. Ritos Aztecas : Las Fiestas de Las Veintenas. 1a. ed. México, D.F.: Instituto Nacional Indigenista.

- Green, Christine : For Curanderos Cures Come From The Ground Up (2020) https://www.whetstonemagazine.com/journal/for-curanderos-cures-come-from-the-ground-up#:~:text=Whenever%20Tonita%20Gonzales%20was%20sick,the%20American%20Southwest%20and%20Mexico.

- Hamann, B. (2003). [Review of Searching for the Secrets of Nature: The Life and Works of Dr. Francisco Hernández; The Mexican Treasury: The Writings of Dr. Francisco Hernández, by S. Varey, R. Chabrán, D. B. Weiner, F. Hernández, & C. L. Chamberlin]. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 17(1), 124–126. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3655382

- Hernández, Francisco, and Simon Varey. The Mexican Treasury : The Writings of Dr. Francisco Hernández. Stanford University Press, 2000.

- Hinton, T. B. (1956). A Description of the Contemporary Use of an Aboriginal Sonoran Food. KIVA, 21(3-4), 27–28. doi:10.1080/00231940.1956.117

- Pappa, M.R., de Palomo, P.P., Bressani, R., 2010. Effect of Lime and Wood Ash on the Nixtamalization of Maize and Tortilla Chemical and Nutritional Characteristics. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 65, 130-13

- Prentice AM. Early life nutritional supplements and later metabolic disease. Lancet Glob Health. 2018 Aug;6(8):e816-e817. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30308-5. PMID: 30012254.

- Santiago-Ramos, D., Figueroa-Cárdenas, J. de D., Mariscal-Moreno, R. M., Escalante-Aburto, A., Ponce-García, N., & Véles-Medina, J. J. (2018). Physical and chemical changes undergone by pericarp and endosperm during corn nixtamalization-A review. Journal of Cereal Science, 81, 108–117. doi:10.1016/j.jcs.2018.04.003

- Sowell, D. (2003). [Review of the book The Mexican Treasury: The Writings of Dr. Francisco Hernandez, and: Searching for the Secrets of Nature: The Life and Works of Dr. Francisco Hernandez]. Ethnohistory 50(4), 742-745. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/51075.

- Torres-Maravilla, E., Méndez-Trujillo, V., Hernández-Delgado, N. C., Bermúdez-Humarán, L. G., & Reyes-Pavón, D. (2022). Looking inside Mexican Traditional Food as Sources of Synbiotics for Developing Novel Functional Products. Fermentation, 8(3), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8030123

- Väkeväinen, K., Hernández, J., Simontaival, A.-I., Severiano-Pérez, P., Díaz-Ruiz, G., von Wright, A., … Plumed-Ferrer, C. (2020). Effect of different starter cultures on the sensory properties and microbiological quality of Atole agrio, a fermented maize product. Food Control, 109, 106907. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106907

- Varey, Simon (2000). Searching for the Secrets of Nature: the Life and Works of Dr. Francisco Hernández. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3964-1.

Websites : Images

- Atole Agrio from Chiapas – https://en.visitchiapas.com/v1/Sour-atole-Comitan-de-dominguez

Atole Agrio (images) – https://atoleagriodifusion.wixsite.com/atoleagrio/elaboracion-de-atole-agrio - Atole de ceniza – https://www.gastrolabweb.com/bebidas/2021/11/8/atole-de-ceniza-el-secreto-para-combatir-el-frio-otonal-asi-se-prepara-17152.html

- Atole de ceniza (ash atole) : https://www.instagram.com/molinopinto/p/CexD1pAjasm/

- Atole de ceniza (ash atole) (Image) : https://www.instagram.com/molinopinto/p/CexD1pAjasm/

- Atole de Ceniza (Receta): https://santacatarina-palopo.com/atol-de-ceniza/

- Atole de Jamaica via Especias Moy on Facebook (Image) – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2551565424945184&set=a.581884735246606

- Atole de Jamaica via Fundación Tortilla (Image) – https://fundaciontortilla.org/Cocina/el_atole_de_jamaica_y_los_sabores_de_tierra_caliente

- Atole de Jamaica (Image) via Sonia Mendez on Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/lapinaenlacocina/reel/C36qr4TAQPY/

- atolli. : https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/atolli

- Chinatolli (recetas) : https://selecciones.com.mx/atole-de-chia-para-bajar-el-colesterol/ ( Atole de chía para bajar el cholesterol) : https://elporvenir.mx/cultural/alimento-que-aporta-omega-3-a-tu-cuerpo-y-reduce-colesterol/728895 (Alimento que aporta omega 3 a tu cuerpo y reduce cholesterol) : https://www.informador.mx/estilo/Salud-La-deliciosa-bebida-que-ayuda-a-reducir-el-colesterol-y-a-proteger-tu-corazon-20240516-0187.html (La bebida que ayuda a reducir el colesterol y a proteger tu corazón)

- Delicioso atole negro tradicional de Michoacán, una delicia Purépecha : https://www.cocinadelirante.com/recetas/delicioso-atole-negro-tradicional-de-michoacan-una-delicia-purepecha

- El Izquiatol, tradición del maíz que #NosLlenaDeOrgullo : https://www.facebook.com/EricCisnerosB/videos/5389443911086929

- Gruel (image) – https://www.tastinghistory.com/recipes/gruel

- Gruel (image 2) – https://stackingthebricks.com/trying-to-sell-nourishing-gruel/

- Necuhtli (definition) Gran Diccionario Náhuatl. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México https://gdn.iib.unam.mx/diccionario/necuhtli/11074

- tlilli. : https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tlilli

- tliltic. : https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tliltic#:~:text=tl%C4%ABltic%20%3D%20black%20(i.e.%20like%20′,Press%2C%202011)%2C%20111.