I briefly look at the masa based drink called atole in a couple of earlier Posts (1)(2) and I recommend you check these out for a little more context (culturally speaking). They’ll introduce you to the core ingredient (and arguably the basis of life in Mexico), the nixtamalised corn dough called masa, and it will introduce you to an archetypal piece of Mexican cooking equipment, the carved wooden “whisk” used to prepare this “drink” (and others) called a molinillo.

Today though I would like to focus on a range of chocolate based atoles. These drinks demonstrate Mexico’s understanding of the ingredient (cacao) and the science (and art) of processing it which I think is still little understood outside of mesoamerica today.

Lets now investigate a range of chocolate beverages in the atole family.

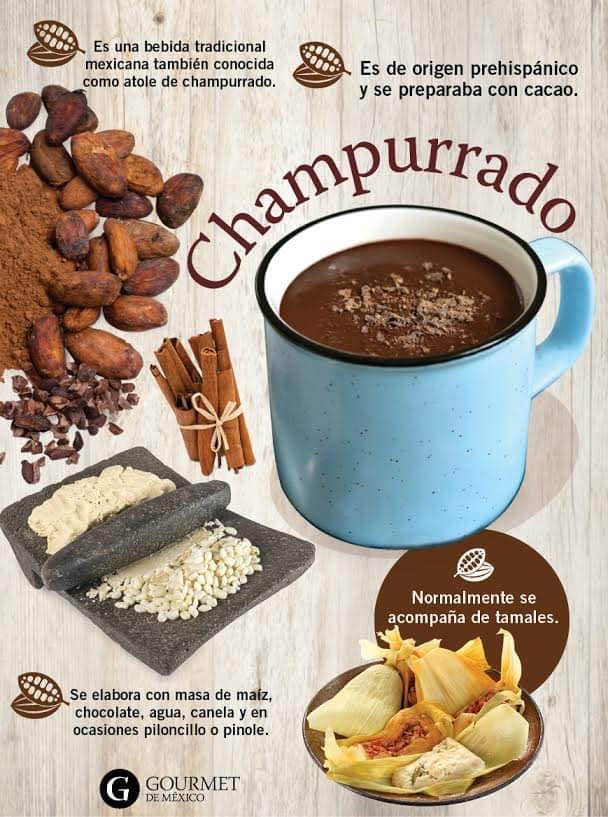

Champurrado is the first on my list as I consider it to be a foundational recipe. It all starts with atole which at its barest minimum is masa diluted in water and then cooked into a hot drink. I go into greater detail in this in A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Appendix 1 : Atole so I’ll not repeat myself here but will branch out specifically into the chocolate variety of atoles (and I guess I use that term a little loosely with some of the drinks on this list). A defining characteristic of these drinks (well perhaps not champurrado so much) is foam.

Foam had spiritual meaning for many of the cultures of central Mexico. Zapotecs believed foam was hope and strength. The foam was the soul of the beverage. And it is the foam which is the defining characteristic of many of these drinks.

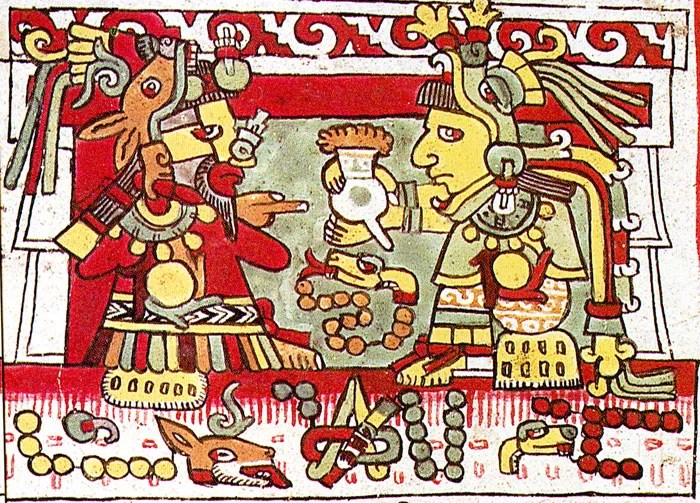

Ritual drinking of cacao: Codex Borgia (also looks like there’s a pot of tamales ready to go too. Tamales are a regular accompaniment to atole)

Codex Borgia

8-Deer (‘Jaguar Claw’) receives a jug of cacao from the hands of his wife 13-Snake (‘Flower Snake’), Codex Zouche-Nuttall

The ability to create a soft billowy foam is a gift. Not all cocineros have it. This is particular of the tejateras of Oaxaca who (in my opinion) are responsible for the most impressive and most difficult to create – let alone master – foam. The secret of its making is held close to the chests of its artisans and you will most certainly be judged on the quality (or lack thereof) of your foam. There is both science and art in its creation.

It looks like 13-Snake had the situation well in hand (or maybe she had excellent kitchen staff?).

Champurrado

Making champurrado with fresh masa

Ingredients (For 6 people)

- 2 bars of chocolate (I use Abuelita brand as it is accessible easily in Australia)

- 1 cone of piloncillo

- 2 cinnamon sticks

- 250 g fresh masa

- 2 litres Water

Method

- In a pot, bring 1 1/2 litres of the water to a boil and add the piloncillo and cinnamon sticks.

- Once the piloncillo has dissolved, add the chocolate and stir to dissolve.

- In a bowl, dissolve the masa with the remaining water.

- Once the masa has dissolved, add it little by little to the pot with the piloncillo and chocolate. Stir constantly so that it doesn’t stick to the pot

- Let it cook for approximately 20 minutes until the masa is well cooked and the champurrado obtains the desired consistency.

Or you can make it with masa harina, which is just fresh masa that has been dehydrated into a flour. Doing this extends the life of fresh masa which can turn sour within a few days (which can be used to make atole agrio – or “sour” atole)

- 1 1/2 cups hot water

- 1/4 cup masa harina

- 3 cups of milk

- 1 to 1 1/2 bars (90 g each) of NESTLÉ ABUELITA Chocolate

Method

- Place the hot water and masa harina in a large pot and whisk until smooth.

- Add the milk and Abuelita chocolate.

- Heat over medium heat, stirring constantly, until it comes to a boil.

- Reduce heat to low; cook, stirring constantly, for 1 to 3 minutes or until thickened to your liking.

- Sprinkle with ground cinnamon if desired. Serve immediately.

Tips:

Anise and cloves can be added to give the Champurrado more flavor and then removed before serving. You can also strain the Champurrado if you want it to be smoother.

Much like plain atole, champurrado can be made as thick (or thin) as you desire. The image below (left) shows a drink as watery as a mug of hot chocolate and on the right it is considerably thicker, almost a custard, look at how it clings to the spoon like a thick sauce.

Champurrado can also be found in “instant” forms.

I have noticed that atole seems primarily to be a smooth textured sweet drink but this is not always the case. I have previously posted on Atole de Grano which is a savoury version of atole and in which the corn is not completely ground (even with some kernels left whole) which provides the drink a grano (granoso) or grainy texture.

Tejate

Tejate, or cu’uhb as it is known in Zapotec (the primary indigenous language of the central valley of Oaxaca) was believed to have been a drink of the gods, which was sent down for humans to enjoy. The secret of its production technique and its recipe is proudly passed down through the generations of women of San Andres Huayapam in Oaxaca. Among the tejate vendors of Oaxaca, there are two distinct groups: those from San Andrés Huayapam and those from San Agustín Yatareni. These two towns are neighbouring communities on the northeast outskirts of Oaxaca City. Women from both communities have taken up the production and sale of tejate as a specialized economic practice. But, the women from Huayapam claim that the folks in Yatareni stole their recipe. Culturally speaking though, tejate is a drink known throughout the Central Valley region of Oaxaca and does not belong to either of these towns alone.

Tejate is the most complex of the cacao based drinks in this Post. Although the ingredients are not particularly different from the others it is the peculiarity of the foam that sets it apart from the others. Zapotec speakers refer to this floral scented foam as ghilo or gyììa cu’uhb – the flower of tejate.

Ingredients

- 250 grams of dried white corn

- 25 grams cacao beans

- 2 mamey seeds (pixtle)

- 20 grams of florecita de cacao (lightly toast these – when the time comes)

- Ice

- Sugar to taste

Method

- Boil your dried corn with ash (preferably encino/oak) or lime to nixtamalize it. Then wash and grind on the metate to make masa.

- Toast the florecita de cacao, cacao, and peeled, split pixtle separately on a comal.

- Peel the cacao and grind it along with the pixtle, and florecita de cacao in a molino or metate until it becomes a paste (masa de pixtle)

- Grind together (on a metate) the masa de pixtle and the corn masa until they are thoroughly combined.

- Place the masa combination in a large clay vessel and slowly add the cold water in increments, kneading and mixing by hand. As you work, the ingredients will release their oils, creating a thick, rich foam that rises to the surface as more water is added. The final amount of water is poured from a height which, together with the hand whipping, raises the characteristic foam to the surface

- Add ice and sugar and serve.

A principal ingredient of Tejate is “rosita de cacao”, which can only be found in San Andres Huayapam (1). Rosita de cacao is not the flower of the cacao tree but rather a white aromatic flower from the Quararibea funebris tree that is botanically entirely unrelated to cacao. The flowers are mucilaginous and thicken the drinks made from it. Schultes (1957) reported that all species of Quararibea have the distinctive odour and the smell remains strong even on herbarium specimens more than a century old.

- which is undoubtedly why they say those blaggards from San Agustín Yatareni pilfered the drink

Cacahuaxochitl, (1) (2) is a beautiful, rare exotic flowering tree of a medium to large size and is considered an obscure spice. It originates from Mexico and South America and is a close relative of Chupa-Chupa (Quararibea cordata). It was known in the ancient times by names of Poyomatli, Xochicacaohuatl or Cacahuaxochitl. See Xochipilli : Intoxicating Scent. for a little more on this flower.

- The epithet funebris meaning “of funerals, funereal” comes from the observations reported by Pablo de La Llave, who published the first botanical description of the plant. In Izucar, funerals were held under the lowest branches of their one large tree.

- also known as rosita de cacao, flor de cacao, madre de cacao

The flower is so important within the culture of the Aztecs that its image is one of the flowers posited to be carved into the Tlamanalco statue of Xochipilli. This actually makes a lot of sense as the Aztecs held a great love of flowers. Typically the flowers are said to be those of intoxicating (or hallucinogenic) plants (Wasson 1973) (Schultes etal 2001) but this theory seems to be holding less water as more culturally specific research is undertaken. See the following for some of the research (and my thoughts) on this. The plant is theorised to have possible hallucinogenic effects due to its chemistry (although there seems to be no record of how it is used in this manner) (Zennie and Cassady, 1986)

Xochipilli. The Prince of Flowers

Xochipilli : Intoxicating Scent.

Xochipilli. The Symbolism of Enrique Vela

Pixtle. The mamey “bone”

A uniquely Mexican ingredient little known outside of the Americas.

Pouteria sapota, the mamey (1) sapote, is a species of tree native to Mexico and Central America. Similar in size and shape to a mango it has a lightly furry brown skin and its sweet flesh ranges in colour from orange to salmon pink.

- chacal haaz in Mayan

The fruit, which is edible only when ripe, has an elusive flavour (which I am not even going to try describe in my own words). It has variously been described as being fruity…..

- a combination of peaches, apricots and prunes

- a blend of peach, apricot, and raspberry

which then morphs into the sweetly spiced and vegetal……

- sweet taste, almost like a blend of vanilla and caramel

- a brown sugar-covered sweet potato, with notes of pumpkin, caramel and cantaloupe

- a mixture between a soft sweet potato, pumpkin, pumpkin pie, a hint of cinnamon in there, honey, and even a bit of cantaloupe

and then obtains a herbal/nutty aspect……

- a complex sweet and savory flavor, containing subtle notes of vanilla, nutmeg, apricots, and root beer mixed with honeyed pumpkin, squash, and sweet potato nuances.

- a mixture of “sweet potato, pumpkin, honey, prune, peach, apricot, cantaloupe, cherry, and almond”.

or do they?……

- do NOT taste like sweet potato! They taste like almond/maraschino cherries and a hint of a like an Amaretto liqueur flavour, and that flavour gets more and more intense the more closely you eat toward the skin.

Obviously a subjective thing this mamey flavour.

Medicinal use of the fruit

Mamey fruit contains antiseptic properties and is often recommended to help calm the nervous system, soothe an upset stomach and alleviate headaches. Mamey has been found to reduce the risk of colon cancer, improve immune function, and help to protect against heart disease and osteoporosis. It is also excellent for helping to alleviate hypertension and the symptoms of cardiovascular disease. Mamey is great for eye and skin health and can help to prevent age-related macular degeneration, cataracts and skin cancer (Gomez-Jaimes etal 2009)( Lakey-Beitia etal 2022)( Yahia etal 2011)

The mamey seed is often called hueso (or huesito) de mamey which means the “bone” of the mamey. This can be derived from its other name “pixtle” which comes from the Nahuatl word “pitztli,” meaning “bone” or “seed.

The seed contains trace amounts of toxic compounds. However, when used in traditional culinary practices as pixtle, the seeds are processed in ways that reduce their toxicity, such as soaking and cooking. Caution is advised when consuming mamey sapote seeds in any form

Aqueous extracts of other components obtained from the seed the of the mamey sapote show potential benefits relieving acute and chronic pain in patients after surgical procedures. (Aragon-Martinez etal 2017). The analgesic effect in patients might be associated with the actions of polyphenols, carotenoids, and secondary metabolites present in the natural extract against the nitroxidative effects of reactive species alongside the flavonoid-related activation of serotonin (5-HT) and opioid receptors.

An oil rich in essential fatty acids (particularly monounsaturated oleic acid), vitamins, and antioxidants can also be pressed from the seed. The emollient properties of the oil can help to soften the skin and restore its natural moisture barrier and its anti-inflammatory properties soothe irritated skin and can help treat conditions like eczema and psoriasis, acne, and others. This oil has been used for the treatment of coronary, rheumatic, and renal diseases (Morton, 1987).

Tejate drinking vessels

Tejate (along with most of the drinks found here) is traditionally drunk from a vessel called a “jicara” which has been made from the dried fruits of the calabash tree (Crescentia cujete)

Tejate is also a nutritionally and medicinally active drink

The flowers have been used since pre-Columbian times by the Zapotec lndians of Oaxaca, Mexico as an additive to chocolate drinks and medicinally as an antipyretic, a cough remedy, to control “psychopathic fear” and to regulate the menses (Rosengarten, 1977).

The consumption of Tejate has been shown to decrease the glucose content in the blood (González-Amaro et al., 2015). Formerly the natives of the Oaxaca region used it to treat anxiety, cough and fever, or as a remedy for an upset stomach (Alija, 2017).

The corn used for this recipe was nixtamalised in an alkaline solution of water and hardwood ashes (instead of the calcium hydroxide – cal – typically used to create the alkalinity needed to transform a rock hard maize kernel into a substance suitable for producing the properties required to make a soft pliable dough) (1). The ashes used also add both nutritional and medicinal factors not present in maize nixtamalised in cal (2). The nixtamalization (1) of the maiz in hardwood ashes (to create a mixture called cuanextle-cuanesle) liberates the corns nutritional value. Cooking gelatinizes maize starch, making it more digestible (Carmody and Wrangham 2009), and the soaking of the maize in ash adds minerals, including iron, potassium, and zinc, absent in corn not processed in these ashes (Pappa etal 2010)( Sotelo etal 2012) and also gives it a medicinal quality (1).

Tascalate

Now we enter the lands of the Maya. This is indicated in this recipe by the use (and a fair bit of it too) of achiote (annatto – Bixa orellana) (1) an ingredient native to the lands of the Maya.

Tascalate – (alternative spelling Tazcalate) is a chocolate drink made from a mixture of roasted maize, roasted cocoa bean, ground pine nuts, achiote and sugar or panela, very common in the Mexican state of Chiapas.

Chiapas is home to the ancient Mayan ruins of Palenque, Yaxchilán, Bonampak, Lacanha, Chinkultic, El Lagartero and Toniná and is home to one of the largest indigenous populations in the country, with twelve federally recognized ethnicities.

Lesser known (well to me anyway) Mayan sites. Places such as Palenque, Yaxchilán, and Bonampak are relatively well known compared to these gems.

Lagartero is a weird one. The image above looks like a model and the pyramids/platforms seem to have slumped/melted like an icecream on a hot day (?)

The drinks name (tascalate) comes from the Nahuatl word “tlaxcalatl “, which in turn is made up of the terms “tlaxcalli” (tortilla)(1) and “atl” (water), so it can be translated as “agua de tortilla” (tortilla water). It is usually drunk in reunions as an agua fresca, and is also related to and dedicated to love.

- for more information on the tortilla (tlaxcalli) and its relationship to Tlaxcala check out Tlaxcales : Prehispanic Corn Biscuits

This drink is interesting in that it was the first one I found (in this category) that used tortillas instead of masa dough as a thickening agent.

Ingredients:

- A kilo of corn tortillas

- 250 grams of roasted cocoa beans.

- 2 teaspoons of cinnamon.

- A quarter of a bar of achiote.

- piloncillo. (al gusto – to taste)

- A litre of water.

Preparation:

- Char the tortillas on the comal (or in a dry pan – on an unoiled grill) and then cut them into pieces.

- Blend them with the cinnamon, cocoa, achiote and a piece of piloncillo (to taste) until they reach a powdery texture.

- Mix 8 tablespoons of the powder with the litre of water

- If necessary, add sugar to taste and beat with a whisk (‘molinillo’) before serving.

- Serve with ice.

So. If you’re not using your stale tortillas to make totopos for chilaquiles then you’re utilising them to make tascalate. Nothing goes to waste.

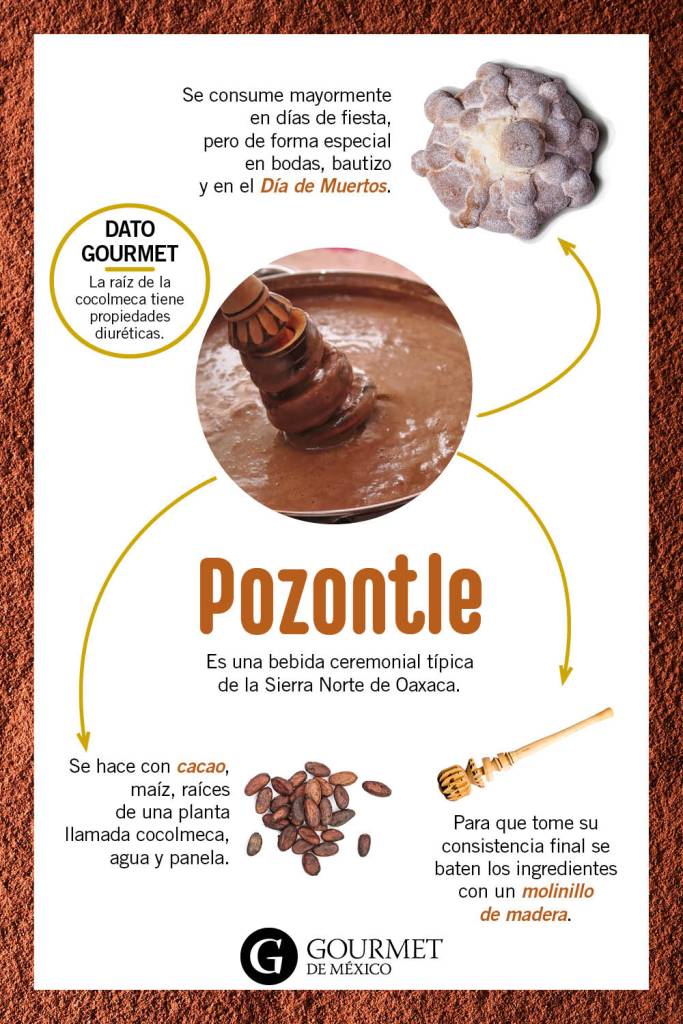

Pozontle

Pozontle (Postontle) – is a ceremonial drink typical of the Sierra Norte of Oaxaca , specifically from the towns of Villa Hidalgo Yalalag, Talea de Castro or Zoogocho. It is consumed mostly on holidays, but especially at weddings, baptisms, and on the Day of the Dead. It is made with cocoa, corn, roots of a plant called cocolmeca, water and panela

Ingredients

- Maíz quebrado – cracked corn (granillo)

- Cal (calcium hydroxide – for nixtamal)

- Water

- Cocoa

- Tender cocolmeca leaves

- Sugar

- Large artisanal gourds (especially for drinks) Jícaras grandes artesanales (especialmente para bebidas)

- Molinillo

Method

- Toast the cocoa for approximately 25 or 30 minutes maximum and then peel it immediately.

- Cook the corn with lime for about 5 or 20 minutes, it should have a smooth texture. Let the corn rest until it is cold, then wash it to remove some of the husk. Grind into masa

- Grind the cocolmeca leaves and the cocoa, the quantity of both has to be equal so that the flavour both the cocoa and the cocolmeca is balanced. You don’t want one overpowering the other

- Once all the ingredients are ready, mix them both and start making small balls of the dough (about the size of a large grape).

- While your making your balls put a pot of water on to boil.

- Take a large jicara and place within 1 to 3 of the masa/cacao balls.

- Once the water is boiling, pour a little into the gourd, do not over fill as we are about to whisk this bad boy with out molinillo..

- Whisk with your molinillo for about 30 minutes adding a little sugar (approximately a teaspoon) until you have a mixture that is neither watery nor thick.

Maíz quebrado

Making your pozontle

Serve in the jicara you whisk it in

Jicaras

Chorote

This drink is consumed in Tabasco. It is made from ground cocoa and fermented nixtamal dough, which is left to rest in a long, oval clay container where it remains all morning. Modern recipes usually omit this step and simply make a dough out of masa, cacao and sugar and make the drink from that.

This delicious drink is accompanied (depending on the occasion), with tamales or pan de muerto (or the appropriate dish traditional to the celebration). Although it is identified as a sweet drink, chorote does not traditionally contain sugar. In Tabasco (the State in Mexico not the hot sauce made in the U.S.A.) t is usually consumed while eating a sweet treat such as dulce de papaya (papaya candy) or dulce de coco (coconut candy).

To enjoy a Tabascan styled chorote try this recipe:

Ingredients:

- 1.5 litres of water

- 100 grams of roasted and ground cocoa

- 200 grams of corn masa

- 200 grams of sugar (optional)

Method

- Bring the water to a boil. When it reaches boiling point, add the cocoa and sugar (if you decide to use it), stirring constantly.

- Remove the mixture from the heat and strain.

- Pour the liquid into a jicara and serve with ice.

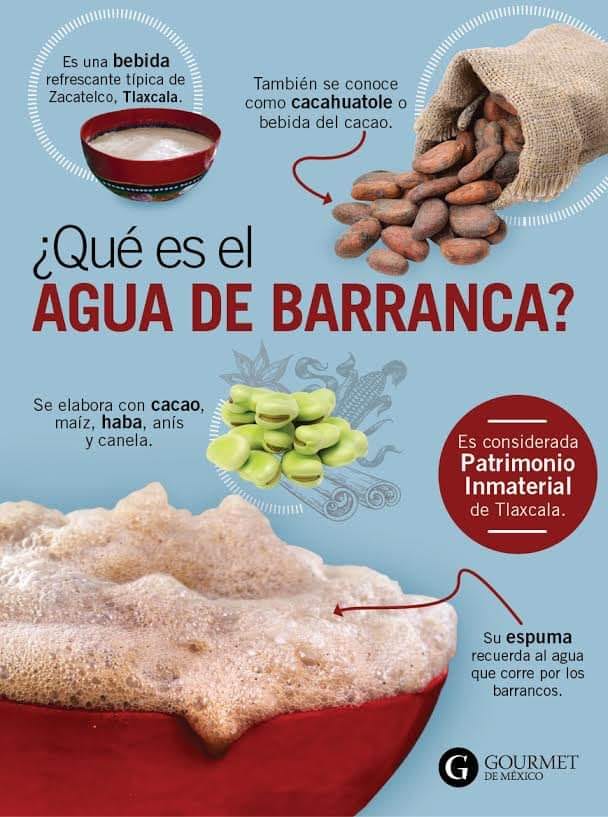

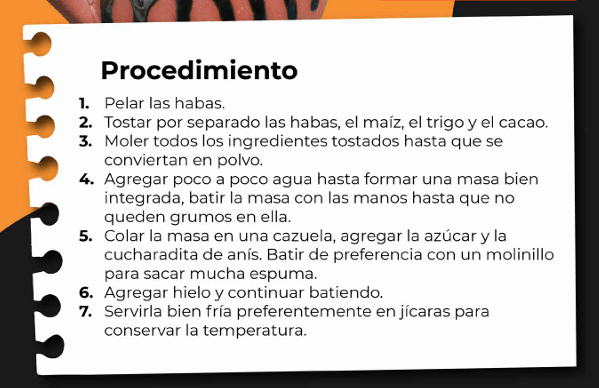

Agua de barranca

Also known as Cacahuatole this traditional cold and frothy drink made from cocoa beans, maize and beans (using broad beans – Vica faba – the faba/haba bean – distinguishes this Tlaxcaltecan product from other drinks made with cocoa or maize)

Ingredients

- 1/2 cup of haba (broad beans)

- 1 tsp. anise

- 1 cinnamon stick

- 1/2 cup wheat )

- 1 cup blue corn

- 1 cup of cocoa seeds

- 2 cups brown sugar

- Water

Method

- First, separately toast the broad beans, corn, wheat and cocoa on the comal. All the seeds/grains must be toasted well.

- Peel the broad beans and remove the skins.

- Put all the toasted ingredients on the metate and grind them until they are powdered.

- Add water little by little to make a dough. Use the metate to work the dough into a smooth(ish) paste.

- Put the paste into a saucepan and gradually add water to blend and mix well. Use your hands to mix well and get rid of all the lumps.

- Strain this mixture into a larger saucepan. Add the sugar and use a molinillo to blend the mix and create foam.

- Add ice and continue mixing (until your foam impresses the very Gods themselves)

- Serve in jicaras.

Bupu

Buppu or “atole espumoso” is a traditional drink of the Zapotecs of the city of Juchitán de Zaragoza in Oaxaca. It is prepared from white atole , cocoa and guie’ chachi flower, known locally as flor de mayo or Cacalosúchil (cacaloxochitl – also known as plumeria or frangipani)

Bupu is another foamy chocolate drink from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. Its name is derived from the Zapotec bu’pu, which means “foam”. First you make a white atole (atole blanco) and then, using a mixture of flowers, spice, sugar and cacao a chocolate foam is made which is then poured atop the atole.

The recipe might look something like this….

First make your white atole (1)……

Atole Blanco

- 2 ¼ pounds corn

- Water

Cook the corn in the water. When cooked, you grind it on a metate-stone grinding pad, or in a blender. Strain it and boil it. Serve it very hot with the chocolate mixture on top. (one thing that is not noted here is cal. Corn used to make atole is first nixtamalised with calcium hydroxide (or its ilk) (2). Grinding (un-nixtamalised) dried corn and using it to make atole will supply you with a lumpy gruel more similar to grits than atole)(3)

- For a little more info on atole check out Atole de Grano and Quelite : Anís de campo : Tagetes filifolia

- Nixtamal

- you might know un-nixtamalised dried ground corn as polenta. This IS NOT suitable for making tortillas, tamales et al.

The chocolate mixure is made from…..

- 9 dried guie’xhuba flowers (a type of night-blooming Jasmine)

- 9 fresh guie’ chachi flowers (a type of plumaria – frangipani).

- 1 ½ pieces of piloncillo (a type of unrefined sugar)

- 6 ounces of cinnamon

- 2 pounds of cocoa.

Toast the cocoa in a comal, and grind it with all the other ingredients, on a metate. Make a paste. Do this at least one day before you make it.

The next day put a little of the paste and hot water in a huge clay pot with a wide mouth. Whip it until it is really foamy, scoop it out and pour it over the atole

Bourreria huanita : Guie’ xuuba’ (Zapotec) (Guie xhuba) also called Izquixochitl (Nahuatl), “Flor del árbol de Esquisuchil”

The present-day name of this tree comes from the phrase , which translates as ‘flower that exudes heavenly glory’ or ‘the mansion of the Gods’. In Tehuantepec, this flower is known as which means ‘tomb flower’. (Jiménez Girón 1979). I do find it interesting that this flower, like the Cacahuaxochitl (Quararibea funebris) used to make tejate is linked to death/dying through funerals/tombs

Traditionally B. huanita has been used to treat respiratory ailments, gastrointestinal infections, burns, and heart diseases (Cruz etal 2008). In Guatemala, it is also used as a sedative or relaxant (Beteta and Haydee 2006). Ethanolic extracts of B. huanita have been reported to exhibit antimicrobial activity (Cornejal etal 2023) and to inhibit growth of Escherichia coli (Cruz et al 2008). The extracts contain alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, and volatile oils (Beteta and Haydee, 2006).

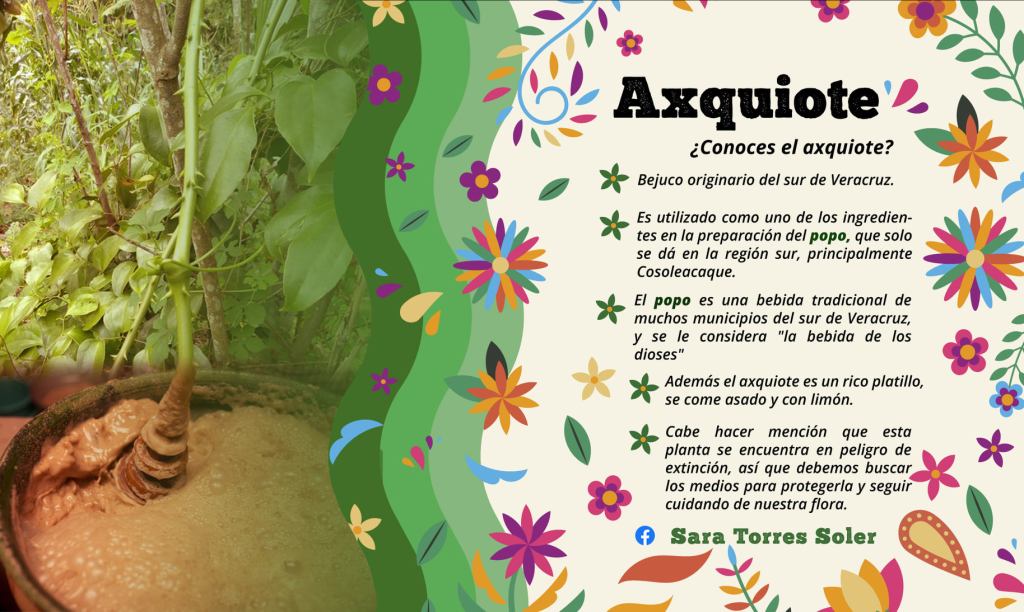

Popo

Popo (1), a foamy and cold drink typical in the south of the state of Veracruz and some areas of the state of Oaxaca (2). It is a ceremonial drink, which is prepared for weddings, baptisms, birthdays, and patron saint festivals. Its main ingredient is cocoa, which is sweetened with sugar or panela (unrefined brown sugar), and is mixed with water; the foaming agents called cocolmecatl (3) and/or chupipi (4), might also be added. Some recipes frequently flavour it with cinnamon and/or anise, and it might be thickened with the nixtamalized maiz dough called masa or ground rice.

- Popo is made by the Nahuatl of Cosoleacaque, Jáltipan and Soconusco; the Mixe-Popolucas of Oluta and Sayula de Alemán; and by the Zoque Popolucas of Texistepec. It is also prepared by the Mazatecs of San Pedro Ixcatlán; and the Chinantecs of San Lucas Ojitlán and San Felipe Usila; both in the north of the state of Oaxaca (Cruz Martinez 2018).

- from the Nahuatl popocti ([thing] “that smokes” or “that foams”),

- azquiote : also called asquiote, axquiote, (Veracruz), cocolmeca, cocolmecate, cozolmeca, (Oaxaca) – Smilax medica and Smilax aristolochiaefolia or Smilax domingensis. Spanish common names include zarzaparrilla, cocolmeca and alambrilla. The name Sarsaparilla means a small bushed vine, from Spanish words zarza (bramble or bush), parra (vine), and illa (small)

- Gonolobus niger

Martínez, Florentino Cruz. (2018) “Hacia una geografía del popo” (PDF). Retrieved March 2, 2022.

Between 1977 and 1978, ethnologist Marina Anguiano once witnessed the preparation of popo in Cosoleacaque (1). It was prepared solely by women and was made primarily for weddings and religious festivals or other important community events. (Cruz Martinez 2018). The same author (Cruz Martinez 2018) also notes that now, the drink “Stripped of its ritual character, it is currently sold, accompanied by tamales, in the market of the municipal capital, among other points of the city.”

- a municipality in the Mexican state of Veracruz. It is located in the south-east zone of the state, about 300 km (190 mi) from the state capital Xalapa.

But the foaming agent par excellence used in Texistepec is the “Magic Vine” called “Axquiote”. A vine that grows almost wild, now more cultivated, but that in recent times has become vitally important for the preparation of Popo.

And the other foaming agent is the “Chupipe” similar to a mango fruit, but climbing like the chayote, with a unique smell.

This atole can is usually either thickened with masa (either nixtamalised or not) or ground rice. The Spanish introduced Asian rice (Oryza sativa) to Mexico in the 1520s at Veracruz as part of the Columbian exchange (1) although there are four species of rice that form the genus Zizania, commonly known as wild rice that are native to and cultivated in North America and recent(ish) research indicates that rice was independently domesticated in South America before the 14th century from Amazonian wild rice (Hilbert et al 2017) so there is a possibility that this drink existed prehispanically looking much as it does now.

- the widespread transfer of plants, animals, and diseases between the New World (the Americas) in the Western Hemisphere, and the Old World (Afro-Eurasia) in the Eastern Hemisphere, from the late 15th century on. It is named after the explorer Christopher Columbus and is related to the European colonization and global trade following his 1492 voyage.

Cruz Martinez’ work (2018) refers to different varieites.

“In the villages of the Coatzacoalcos basin and in La Chontalpa. They prepare this drink by boiling corn without lime (1), washing the nixtamal and grinding it with toasted cocoa in a metate, adding axquiote. This paste is dissolved in cold water to give it the consistency of atole, then poured into a “ralita” (2) cloth, adding sweetener and beating it to obtain foam, serving it in gourds”

- Preparan esta bebida poniendo a hervir el maíz sin cal

- The straining of the mixture using a cloth comes up a couple of times. More on this in a bit.

“In San Pedro Ixcatlán it is prepared with half a kilo of cacao, half a kilo of ground rice, a kilo of nixtamal dough, a kilo of panela or piloncillo and a bunch of cocolmécatl – a vine of which only the tender tips are used”

On a griddle over low heat, roast the cacao, peel it and grind it very well, add ground rice, corn dough and ground cocolmécatl, with this you get a paste. Dissolve the piloncillo in two litres of water. Separately, in a large pot, with four litres of water, dissolve the paste perfectly, strain it in another clean container and beat it with a grinder until you get a rich foam. Serve cold or to taste” (Merlín & Hernández 2000).

Turismo de Tuxtepec supplies us with a little more detail.

This recipe uses no corn masa and relies upon rice as its thickening agent. The recipe has a horchata feel about it. Rice and cinnamon. The rest of the ingredients change its nature completely though.

Ingredients

- 2 cups Cocoa beans

- Fine white sugar or panela

- Foaming agent

- Azquiote – Root, tender stems (sprouts) or flowers (See **NOTES**)

- Chupipi/chupipe Root, tender stems or fruit

- 1 x 5cm Cinnamon stick (or powder)

- 1 tsp Whole (or ground) anise (optional)

- 1 cup Whole rice (Oryza sativa) (long grain I suppose)

- 1 litre water (plus more for soaking/washing the rice)

Method

Day One (yes, thats right, this is an overnighter)

- Toast your cinnamon stick on the comal (or in a dry pan) and roughly break it into pieces.

- Clean your cacao beans to remove any dust. Roast them on the comal over a medium heat taking care not to burn them. Burnt cacao = bitter popo.

- Roughly grind the cacao on a metate so you can loosen and remove the skins.

- Grind the toasted cacao and cinnamon into a paste on the metate (or you could use a mill or a molcajete. I don’t think the blender appropriate here)

- Placed the paste into a grease free container (See **NOTES**), cover and set aside overnight.

- Lightly rinse your rice and place in a bowl cover with 4 cups of water. Cover and set aside overnight.

Day Two

- The next day, the rice is drained and emptied into a bucket, adding the cacao paste and add your foaming agent. The recipe above called for “some axquiote seeds“ (See **NOTES**). These ingredients are ground to a fine soft paste in a mill (or on the metate if you have one and have the strength for it).

- Then, dissolve it in a litre of water and then strain it through a cotton cloth (See **NOTES**)

Sugar and ice cubes are added to the mix and it is brought to a foamy head with a molinillo. (See Mexican Cooking Equipment : The Molinillo if you need more context)

**NOTES**

In the process of making it, women use clean utensils, not contaminated with grease, preferably new because it is believed that it will not foam. (Cruz Martínez 2018)

The recipe above called for the seed of axquiote and noted that “It is believed that the proportion of axquiote (seed) should not be exceeded when mixed with rice and cocoa paste, as it “cuts” or irritates the throat” and that “According to other versions, the mixture should be vigorously beaten and strained twice to avoid this irritation.” This is very interesting as all varieties (whether they used the seed or not) very quite careful in noting the straining of the diluted paste. The care taken in noting this seems to be for more than just straining out lumps and I wonder if it has to do with removing irritants present in the plants. The straining is required for both chupipi and axquiote and all parts of plant so perhaps it is just normal cooking process

Various descriptions of the straining of the paste include….

La pasta se mezcla con agua y se cuela varias veces con un trapo tusor (de algodón) o colador.

The paste is mixed with water and strained several times with a tusor rag (of cotton) or colander. (Popo Tuxtepec Turismo)

La mezcla se cuela en paño de algodón, utilizándose principalmente la tela tusor

The mixture is strained through a cotton cloth, mainly using the tusor cloth (Cruz Martínez 2018)

Esta pasta es disuelta en agua fría para darle la consistencia del atole, secuelaen una tela “ralita”,

This paste is dissolved in cold water to give it the consistency of atole, then poured into a “ralita” cloth

This paste is dissolved in cold water to give it the consistency of atole, then placed in a “thin” cloth (Cruz Martínez 2018)

I bring this up partly for interests sake (etymologically speaking – I love the history of the evolution of words) and because I’m still not entirely convinced that the straining of the diluted cacao paste isn’t being done to remove some kind of physical irritant (which no one actually says outright) such as small hairs (only an example) in the plant material. Cruz Martínez (2018) does speak of cooking and eating the internal flesh of the chupipi noting that when the “white pulp, which roasted over a slow fire, has a pleasant flavor.” He goes on to note that “The interior of this fruit contains hairs.” (but mentions nothing about them being irritant).

These words (concerning the straining) are…..

- Tela : cloth, material, fabric.

- Trapo : cloth, rag

- Tusor : a type of silken cloth, often noted as being “wild” silk. (also written as tussah/tussore). Although the second reference notes it as being un trapo tusor de algodon or a “thin (?) cotton cloth”

- Ralita (as in “tela ralita”) generally this translated into “thin fabric”

The type of cloth used, although likely well known to Mexicanos, is still somewhat unknown to me (although I can imagine what it might be). It mirrors the use of cheesecloth as a fabric strainer. I do think that cheesecloth might be too porous for this job though (especially if the cloth is filtering out an irritant) so I’d be inclined to use a good (and clean) cotton tea towel (or paño de cocina).

Another interesting facet of this drink (and not one bought up in local sources) is the overnight storage of the cacao/rice paste. Although not stored for long, fermentation occurs. This fermentation creates beneficial probiotic organisms which have positive effects of the drink itself (help prevents spoilage) and on the person consuming it. More study is needed in this area as another fermented Mexican drink, pulque (1), has been extensively studied for it health/nutrition benefits.

The study notes “During the rice soaking process, spontaneous fermentation occurs, promoting the growth of fermentative microorganisms, especially lactic acid bacteria (BAL)” (Ghosh et al., 2014). “BAL produce various antimicrobial compounds, including organic acids, creating a low pH environment that is detrimental to the development and survival of pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms” (Mgomi et al., 2023).

Espuma

Espuma – an atole with very fine foam made with a mixture of white pataxte, red cocoa, rice and cinnamon that is prepared for important festivals such as the Day of the Dead, mayordomías or weddings.

Pataxte, botanically classified as Theobroma bicolor, is a rare species belonging to the Malvaceae family. The fruits, also referred to as pods, grow at the top of a slow-maturing tree, reaching 7 to 20 meters in height, depending on the variety. Pataxte is native to the Americas and is one of the largest fruits within the Theobroma genus. Each tree produces 15 to 40 fruits per season, and the fruits naturally fall from the tree when ripe, allowing foragers to gather them off the ground. Pataxte is distinct from cacao as the fruits hang from branches at the top of the tree, while cacao forms from the trunk. Pataxte is also known as Bacao, Mocambo, Marroca, Macao, Jaguar Cacao, Macambu, Majambo, Cacao Blanco, Wakampe, and Pataxte Cacao. Several varieties exist throughout Central and South America, varying in flavor, color, and shape, and the arils and seeds are edible in raw and cooked preparations. In the modern day, Pataxte is a rare species often overshadowed by cacao. The fruits are a treasured food of ancient civilizations and have been preserved among select people groups as a specialty ingredient.

Pataxte was a sacred ingredient in the Mayan Empire and was often paired with cacao to make a ceremonial drink. Pataxte is representative of male energy and is said to resemble male genitalia, while cacao represents feminine energy, taking an abstract form of a breast. The seeds from the two pods are combined to create a beverage that was thought to increase fertility and nourish the body’s energy. Cacao and Pataxte were also mixed with corn in the drink, as corn was regarded as the source of life. Pataxte was used in the ceremonial beverage to add a frothy foam at the top. The foam was thought to contain valuable life force and was consumed at important gatherings and celebrations. Pataxte and Cacao are still used in variations of the ancient Mayan beverage in the Oaxaca Valley, Mexico, in the present day, and the practice of making this drink is a complex process. Pataxte seeds are buried underground to ferment for 1 to 2 years, and when they are unearthed, they develop a crumbly, chalk-like consistency and a white hue. The fermented seeds are combined with cacao to make a foam on top of a drink made from the flower known as rosita de cacao, toasted mamey sapote seeds, toasted masa, cacao, water, and sugar to create a thick beverage. The drink is still served at weddings, religious services, and familial gatherings today.

A chocolate mixing tool that isn’t a molinillo. The alcahuete.

The alcahuete originally has a handle or handle carved with different figures, especially animals, it is a wooden utensil in the shape of a letter opener that is used to mix the traditional chocolate-atole of Oaxaca. The diner mixes the foam of the cocoa that is put on top of the chocolate; the alcahuete enters and exits diagonally to integrate the foam with the liquid while drinking; it acts as a spoon because there are those who take the foam of the drink to their mouth with it and then drink the atole.

In the mercado at Zaachila

Doña Carmela Iriarte comments: “The ingredients are toasted rice and two types of cocoa, one called patlale and the other is normal cocoa that is used for chocolate and cinnamon; the rice is toasted on a clay griddle in Todos Santos , and is the one that sells the most; I prepare several kilos and end up selling them all.”

Preparing the foam takes less than an hour. The ingredients are passed through the metate twice; this grinding produces a paste that is soaked in a mixer with cold water; with the movement of the mixing, the ingredients quickly “rise” until small bubbles are obtained, which are collected with a gourd and placed in another container that already contains hot white atole; finally, a little sugar is added.

“It is served with hot atole; the foam is cold and the atole is hot” (Salvadorans might debate this though….)

Chilate

Chilate – a drink prepared with cocoa, rice, cinnamon and sugar. It is a mestizo drink with African influences originally from Guerrero, México. The cuisines of the Gulf Coast were strongly influenced by Africans who were “imported” through the Port of Veracruz into the Americas as slaves.

This African influence is interesting particularly with regards to a primary ingredient in this drink, rice. Now I know I said earlier (in the bit on Popo) about rice being bought to the Americas by the Spanish as part of the Colombian Exchange but there is also a strong argument that rice was bought from Africa and that the Portuguese carried it as a food for the slaves they also carried in the holds of their ships. (Carney 2001 & 2009)(Danrebo 2020)(Stokstad 2007) (and this was after only a brief search. There is a ton of information out there and no less than a thesis required to examine it)

According to Fundación Casa de México this recipe is typical of the Costa Chica in the state of Guerrero

Ingredients:

- 400 gr. raw cocoa

- 400 gr. of white rice

- 1 x 5cm cinnamon stick

- 250 gr. Piloncillo (or panela – a type of brown/raw sugar))

- 6 litres of cold water

- Ice cube

Method

- On a comal, toast the cocoa for 20 minutes over very low heat. Remove and toast the cinnamon.

- Wash the rice and soak for 1 hour in cold water.

- Break up your cone of piloncillo in the molcajete (or wrap it in a tea towel and belt the crap out of it with a mallet)

- Once you’ve prepared your ingredients we need to grind them separately. Start with the rice. Drain it and grind it on your metate as finely as you can (alternatively use a hand powered Molino or a blender), then grind the cacao beans (skins and all) and cinnamon. We are going to strain the mix later so “bits” in the paste aren’t going to be a problem.

- If making it in a blender/food processor, you can add a little of the rice, which has more moisture, and the broken up piloncillo cone.

- Now grind all the ingredients together to obtain a thick paste. The grinding can cause the paste to become hot. Allow it to cool before using it.

- Traditionally this drink is prepared in a wide container like a bowl and is mixed with the hands. Add the water little by little mixing with your hands using your fingers like a whisk. For the last bit and to create a foam pour the drink from one container to another from a height of 50cm or more to agitate up a nice foam.

- Add ice and drink

Commercial and prepackaged chilate

Juan Carlos Alonso founded the company Acadeli. Juan is originally from Ayutla de los Libres, an indigenous municipality on the Costa Chica of Guerrero, and he turned the activity of making chilate that he and his parents carried out simply to get by into a promising business.

Juan graduated from the Faculty of Accounting and Administration of the Autonomous University of Guerrero and in 2017 he launched the concept of selling chilate in tetrapak and powder form with the aim of preserving an ancient practice and bringing the flavour of this drink to the palates of Guerrero and Mexican families.

Juan Carlos decided to sign up to participate in Shark Tank Mexico to help get his venture off the ground and he was blown away by the response.

The young man from Guerrero went for an investment of 200 thousand pesos in exchange for a 20% stake in his company and to his surprise, all the “sharks” were interested in his product and three of them offered him 300 thousand pesos in exchange for 30% of their company.

Guatemalan Chilate

Further south the Guatemalans do something similar but they have dropped the inclusion of rice. This recipe also begins with nixtamalizing your own corn. This step can be skipped, either use fresh masa or even reconstituted masa harina (although this last one is the least desired – still good but). They also switch things up a bit by making a standard atole and then “floating” a chocolate based drink on top in the manner of some kind of hot atole cocktail

Ingredients

- 2 pounds of corn or you can substitute 1 ½ pounds of cornmeal.

- 2 pounds of cocoa beans or 1½ pounds of cocoa powder (optional)

- ½ cup of ash

- 3 litres of water

Method

To prepare the dough

- Cook the corn in a mixture of water and ash for approximately 3 hours, until the grain is soft.

- Once cooked, wash the corn (to remove the hard outer covering of the kernel – called the pericarp), drain it and take to the mill to obtain the masa (unless you live in Mexico you are not likely to have ready access to a mill)

On a comal (or in a dry frying pan), brown the cocoa (taking care not to burn it) and remove the shells of the “beans”.- Grind the cacao beans to a paste, which you dilute in 500ml of water and heat

To prepare the drink

- Dissolve the masa in 500ml of water. Once dissolved, strain using a cloth or fine strainer to remove lumps.

- Boil this masa mixture in a pot, stirring constantly. When it starts to boil, add 500ml more water and boil for 10 more minutes so that the atole thickens.

- To serve

- In a cup, serve ¾ of the atole and float ¼ cup of the cocoa/chocolate drink on top. This mix of flavours makes Guatemalan chilate unique.

Garnishes

The Guatemalans go a little left field here

The ideal decoration is sliced hard-boiled egg, chopped parsley, hard cheese and onion rings. (La decoración ideal es el huevo duro en rodajas, perejil picado, queso duro y aros de cebolla.)

Salvadoran Chilate

Now we branch out a little further and look at a chilate from El Salvador.

This variety is served like the Guatemalan variety (hot) and they note that it is not at all like the Mexican version which is “served with ice”. This one doesn’t mess about with masa and is based on masa harina instead.

Ingredients

• 160 g of nixtamalized corn flour (Maseca)

• 5 cm piece of ginger , grated

• 10 whole allspice berries

• 2 l water

Method

- In a large nonstick saucepan, dissolve the corn flour in 2 quarts of water.

- Place the pan over low heat. Add the ginger, allspice and mix.

- Bring to the boil and simmer for 25 minutes, stirring regularly and making sure it doesn’t stick to the bottom of the pan.

- Serve the drink with banana jam, huevo nuégados, yuca nuégados or masa nuégados, all covered with panela sugar syrup.

Sirva la bebida con dulce de banana, nuégados de huevo, nuégados de yuca o nuégados de masa, todos cubiertos con miel de panela.

Look for this at your mercado if you’re interested.

These drinks are an example of the advanced understanding of the cacao bean and how it can be utilised. More information can be found in previous Posts regarding the valuable nutritional and medicinal qualities of many of the ingredients listed above.

References

- Aragon-Martinez, Othoniel H & Martinez-Morales, JF & Alonso-Castro, Angel & Isiordia-Espinoza, Mario & González Rivera, María Leonor & Galicia-Cruz, Othir. (2017). Could the seed of mamey sapote relieve the postoperative pain?. Transylvanian Review. 25..

- Beteta O, and Haydee G 2006. Actividad antifúngica de los extractos etanolicos de la flor de Bourreria huanita y la hoja de Lippia graveolens y sus particiones hexanica, clorofórmica, acetato de etilo y acuosa contra los hongos Sporothrix schenckii y Fonsecaea pedrosoi. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

- Carmody, R.N., Wrangham, R.W., 2009. The energetic significance of cooking. J Hum Evol 57, 379-391

- Carney, Judith A. (2001) African Rice in the Columbian Exchange : The Journal of African History, Vol. 42, No. 3 2001, pp. 377-396 : Cambridge University Press DOI: Io.IoI7/Soo218537100o7940

- Carney, Judith A. (2009) Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas : Harvard University Press : ISBN 0674029216, 9780674029217

- Cornejal N, Pollack E, Kaur R, Persaud A, Plagianos M, Juliani HR, Simon JE, Zorde M, Priano C, Koroch A, Romero JAF. Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Theobroma cacao, Bourreria huanita, Eriobotrya japonica, and Elettaria cardamomum – Traditional Plants Used in Central America. J Med Act Plants. 2023 Mar;12(1):1-17. doi: 10.7275/wets-9869. PMID: 38234988; PMCID: PMC10792510.

- Cruz SM, García EP, Letrán H, Gaitán I, Medinilla B, Paredes ME, Orozco R, Samayoa MC and Cáceres A 2008. Caracterización química y evaluación de la actividad biológica de Bourreria huanita (Llave and Lex.) Hemsl. (Esquisuchil) y Litsea guatemalensis Mez. (Laurel). Informe Final del Proyecto, Dirección General de Investigación, Universidad de San Carlos, Guatemala.

- Cruz Martínez, F. (2018). «Hacia una geografía del popo». Gobierno de Texistepec. : https://www.scribd.com/document/428922174/Hacia-Una-Geografia-Del-Popo

- Danrebo (2020) West Africa in Mexican rice cultivation and gastronomy : African Studies Library : Resources for African Studies academic research, teaching, learning, and awareness. https://africanstudieslibrary.wordpress.com/2013/03/27/west-africa-in-mexican-rice-cultivation-and-gastronomy/

- de La Llave, Pablo; Lexarza, Juan José Martinez de (1825). Novorum Vegetabilium Descriptiones II. Mexico: Martin Rivera.

- Dillinger, T. L., Barriga, P., Escárcega, S., Jimenez, M., Lowe, D. S., & Grivetti, L. E. (2000). Food of the Gods: Cure for Humanity? A Cultural History of the Medicinal and Ritual Use of Chocolate. The Journal of Nutrition, 130(8), 2057S–2072S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.8.2057s

- Gomez-Jaimes, R., Nieto-Angel, D., Teliz-Ortiz, D., Mora-Aguilera, J. A., Martinez Damian, M. T., & Vargas-Hernandez, M. (2009). Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H. E. Moore and Stearn. Agrociencia, 43, 37−48.

- González-Amaro, Rosa & Figueroa, Juan & Perales, Hugo & Santiago-Ramos, David. (2015). Maize races on functional and nutritional quality of tejate: a maize-cacao beverage. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft und-Technologie.

- Hernández-Nolasc, Zuemy, Acateca-Hernández, Mariana Inés; Flores-Andrade, Enrique; Uzárraga-Salazar, Rafael; Castillo-Morales, Marisol (2024) Comprendiendo el efecto del tiempo de fermentación sobre las características fisicoquímicas y microbiológicas del “Popo”, una bebida tradicional Mexicana “Understanding the effect of fermentation time on the physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of “Popo”, a traditional Mexican beverage” : BioTecnología, Año 2024, Vol. 28 No 1 : Facultad de Ciencias Químicas, Universidad Veracruzana. Prolongación Oriente 6, Orizaba, Veracruz, 94340, México.

- Hilbert, L., Neves, E.G., Pugliese, F. et al. Evidence for mid-Holocene rice domestication in the Americas. Nat Ecol Evol 1, 1693–1698 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0322-4

- Jamieson, G. S., & McKinney, R. S. (1931). Sapote (mammy apple) seed and oil. Oil & Fat Industries, 8(7), 255–256. doi:10.1007/bf02574575

- Jiménez-Fernández, Maribel & Juárez-Trujillo, Naida & Mendoza, Maria & Monribot-Villanueva, Juan & Guerrero-Analco, José. (2023). Nutraceutical potential, and antioxidant and antibacterial properties of Quararibea funebris flowers. Food Chemistry. 411. 135529. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135529.

- Jiménez Girón, Eustaquio (1979) Guía Gráfico-Fonémica para la Escritura y Lectura del Zapoteco

- Lakey-Beitia J, Vasquez V, Mojica-Flores R, Fuentes C AL, Murillo E, Hegde ML, Rao KS. Pouteria sapota (Red Mamey Fruit): Chemistry and Biological Activity of Carotenoids. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2022;25(7):1134-1147. doi: 10.2174/1386207324666210301093711. PMID: 33645478.

- Merlín Arango, Roger & Hernández López, Josefina (2000) Cocina indígena y popular 42 : Recetario mazateco de Oaxaca – México, CONACULTA, Dirección General de Culturas Populares e Indígenas D.F. ISBN: 9701853865. LOC classification: TX716.M4 M47 2000

- Mgomi FC, Yang Y, Cheng G, Yang Z (2023) Lactic acid bacteria biofilms and their antimicrobial potential against pathogenic microorganisms. Biofilm 5: 100118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioflm.2023.100118

- Morton , J. 1987 . “ Sapote ” . In Fruits of warm climates , Edited by: Morton , J.F. 398 – 402 . Miami , FL

- Norton, Marcy. “Tasting Empire: Chocolate and the European Internalization of Mesoamerican Aesthetics.” The American Historical Review, vol. 111, no. 3, [Oxford University Press, American Historical Association], 2006, pp. 660–91, https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.111.3.660.

- Rosengarten, F. (1977) “An unusual spice from Oaxaca: The flowers of Quararibea funebris” Bot. Mus. Leaflets, Harvard University 25 (7):I 84-2 I 5.

- Rosenswig, Robert M. “Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Culture History of Cacao – Edited by Cameron L. McNeil.” Bulletin of Latin American Research, vol. 27, no. 3, July 2008, pp. 435–437. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1111/j.1470-9856.2008.00278_4.x.

- Schultes, Richard Evans (1957). “The Genus Quararibea in Mexico and the use of its flowers as a spice for chocolate”. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University.

- Schultes, Richard Evans, Albert Hofmann, and Christian Rätsch. (2001) Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press

- Soleri, Daniela; Castillo Cisneros, María del Carmen ; Aragón Cuevas, Flavio; & Cleveland, David A. (2022) Tejate through time and space “ A traditional Mesoamerican maize and cacao beverage moves from Oaxaca to Oaxacalifornia” : an English adaptation of: Soleri D., Castillo Cisneros, M. del C., Aragón Cuevas, F., Cleveland D.A. (2022) El tejate: a través del tiempo y el espacio. In La comida oaxaqueña. De la época prehispánica a la actualidad. Arqueología Mexicana, núm. 173:42-49.]

- Sotelo, A., Soleri, D., Wacher, C., Sanchez-Chinchillas, A., Argote, R.M., 2012. Chemical and Nutritional Composition of Tejate, a Traditional Maize and Cacao Beverage from the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 67, 148-155.

- Stokstad, Erik (2007) American Rice: Out of Africa : https://www.science.org/ : doi: 10.1126/article.32733

- Stross, Brian. “Food, Foam and Fermentation in Mesoamerica.” Food, Culture & Society, vol. 14, no. 4, 2011, pp. 477–501., https://doi.org/10.2752/175174411×13046092851352.

- Wasson, R. G. (1973). THE ROLE OF “FLOWERS” IN NAHUATL CULTURE: A SUGGESTED INTERPRETATION. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, 23(8), 305–324. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41762283

- Yahia, E. M., Gutiérrez-Orozco, F., & Arvizu-de Leon, C. (2011). Phytochemical and antioxidant characterization of mamey (Pouteria sapota Jacq. H.E. Moore & Stearn) fruit. Food Research International, 44(7), 2175–2181. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2010.11.029

- Zennie, Thomas M., and John M. Cassady. “Funebradiol, a New Pyrrole Lactone Alkaloid from Quararibea Funebris Flowers.” Journal of Natural Products, vol. 53, no. 6, 1990, pp. 1611–1614., https://doi.org/10.1021/np50072a040.

Websites

- Recipe for Tascalate : https://gospelmissionary.blogspot.com/2009/08/recipe-for-tascalate.html

Images

- Agua de barranca – Cacao Franks – https://oem.com.mx/elsoldetlaxcala/tendencias/lanzate-por-un-agua-de-barranca-para-celebrar-el-dia-mundial-del-cacao-16379909

- Agua de barranca recipe – https://lossaboresdemexico.com/agua-de-barranca-o-cacahuatole/

- Axquiote – Chupipe image – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2629095097206208&set=a.876614405787628

- Bupu – https://fundaciontortilla.org/Emprendimientos/el_bupu_de_esperanza_una_bebida_tradicional_istmena

- Bupu – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=149019560208738&set=pcb.149019653542062

- Cacaloxochitl – https://productospronamed.com/cacaloxochitl

- Champurrado – https://dorastable.com/how-to-make-champurrado/

- Champurrado (thin) – https://www.maricruzavalos.com/web-stories/champurrado-recipe/

- Champurrado (thick) – https://www.muydelish.com/web-stories/champurrado/

- Chilate images – https://www.tasteatlas.com/chilate : https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/menu/chilate-una-bebida-tradicional-de-guerrero-que-puedes-hacer-en-casa/ : https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2726441207635109&set=a.1449957991950110

- Chorote image – https://www.elheraldodetabasco.com.mx/cultura/chorote-la-bebida-ancestral-de-tabasco-7655554.html

- Cocolmeca image – https://gourmetdemexico.com.mx/gourmet/cultura/cocolmeca-bebida-oaxaca-veracruz/

- Pozontle images – https://larevistadelsureste.com/pozontle-la-deliciosa-bebida-ancestral-de-oaxaca-conoce-su-preparacion/

- Espuma alcahuetes – https://sucedioenoaxaca.com/2017/07/19/exposicion-espuma-las-bebidas-de-cacao-en-oaxaca-llega-a-zaachila/

- Espuma y pan – https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1757141347817252&id=438791389652261&set=a.446392118892188

- Fruiting branches of the calabash tree (Crescentia cujete) – By Rik Schuiling / TropCrop-TCS – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61309843

- guie’ xuuba’ flowers – https://dictionaria.clld.org/units/diidxaza-E1155

- Huesitos de mamey (pixtle) – https://artricenter.com.mx/blog-artritis-reumatoide-beneficios-del-mamey/

- Mamey – https://agenciadenoticias.unal.edu.co/detalle/en-el-mamey-rojo-del-pacifico-habria-una-esperanza-para-el-tratamiento-del-alzheimer

- Popo Tuxtepec Turismo – https://tuxtepecturismo.com/en/what-to-do/gastronomy/typical-drinks/

- Popo Veracruzano – https://oem.com.mx/diariodexalapa/tendencias/que-es-el-popo-y-como-se-prepara-este-bebida-tipica-del-sur-de-veracruz-13430866

- Pozontle recipe : Gastronomía Tradicional Oaxaqueña : https://proyecto1gtics.blogspot.com/2018/11/pozontle.html

- Pataxte – https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=725537615493889&id=101290807918576&set=a.101304784583845&locale=ru_RU : https://specialtyproduce.com/produce/Pataxte_Fruit_23159.php : https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=134239881760593&set=pcb.134239995093915

- Tascalate – https://www.facebook.com/Cafeleeria/photos/a.131898153487219/1908772619133088/?type=3&locale=es_LA

- Tascalate con hielo – https://www.milenio.com/estilo/gastronomia/tascalate-de-que-esta-hecho-como-se-prepara-y-beneficios-para-salud

- Whisking Popo – https://www.facebook.com/watch?v=574812646344722