also called : pixtli, piztli. I have also seen it written as piscle, pixcle, pixle, pixte.

Todays ingredient is a seed. The seed of the fruit called a mamey sapote.

Borne of a tree called Pouteria sapota.

Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H.E. Moore & Stearn.

Synonyms

- Achras mammosa Bonpl. ex Miq. nom. illeg.,

- Bassia jussaei Griseb.,

- Calocarpum huastecanum Gilly,

- Calocarpum mammosum var. bonplandii (Kunth) Pierre,

- Calocarpum mammosum var. candollei (Pierre) Pierre,

- Calocarpum mammosum var. ovoideum (Pierre) Pierre,

- Calocarpum sapota (Jacq.) Merr.,

- Calospermum mammosum var. bonplandii (Kunth) Pierre,

- Calospermum mammosum var. candollei Pierre,

- Calospermum mammosum var. ovoidea Pierre,

- Calospermum parvum Pierre,

- Lucuma bonplandii Kunth,

- Sapota mammosa Mill.,

- Sideroxylon sapota Jacq.

Common Names

- Brazil : Mamei, Mamey Sapote;

- Columbia : Zapote De Carne;

- Costa Rica : Mamey, Zapote Colorado;

- Cuba : Mamey Colorado, Mamey;

- El Salvador : Zapote Grande;

- Ecuador : Mamey Colorado;

- French : Sapotier, Sapotier Jaune D’oeuf, Grand Sapotillier, Grosse Sapote;

- German : Große Sapote, Mamey-Sapote, Marmeladenpflaume (Marmalade plum – Jam plum)

- Guadeloupe : Sapote À Crème;

- Haiti : Sapotier Jaune D’oeuf, Grand Sapotillier;

- Indonesia : Ciko Mama;

- Jamaica : Marmalade Fruit, Marmalade Plum;

- Malaysia : Chico-Mamey, Chico-Mamei;

- Martinique : Grosse Sapote;

- Mexico : Chachaas, Chachalhaas, Tezonzapote , Zapote;

- Nicaragua : Guaicume;

- Panama : Mamey, Mamey De La Tierra;

- Philippines : Chico-Mamei, Chico-Mamey, Mamei ( Tagalog );

- Portuguese : Zapote De Carne, Mamey Mamey De La Tierra;

- Spanish : Mamey Colorado, Mamey Rojo, Mamey Zapoteo, Sapota, Sapote, Sapote Colorado, Zapota Grande, Zapote;

- Venezeula : Zapote;

- Vietnamese : Tru’ng Ga.

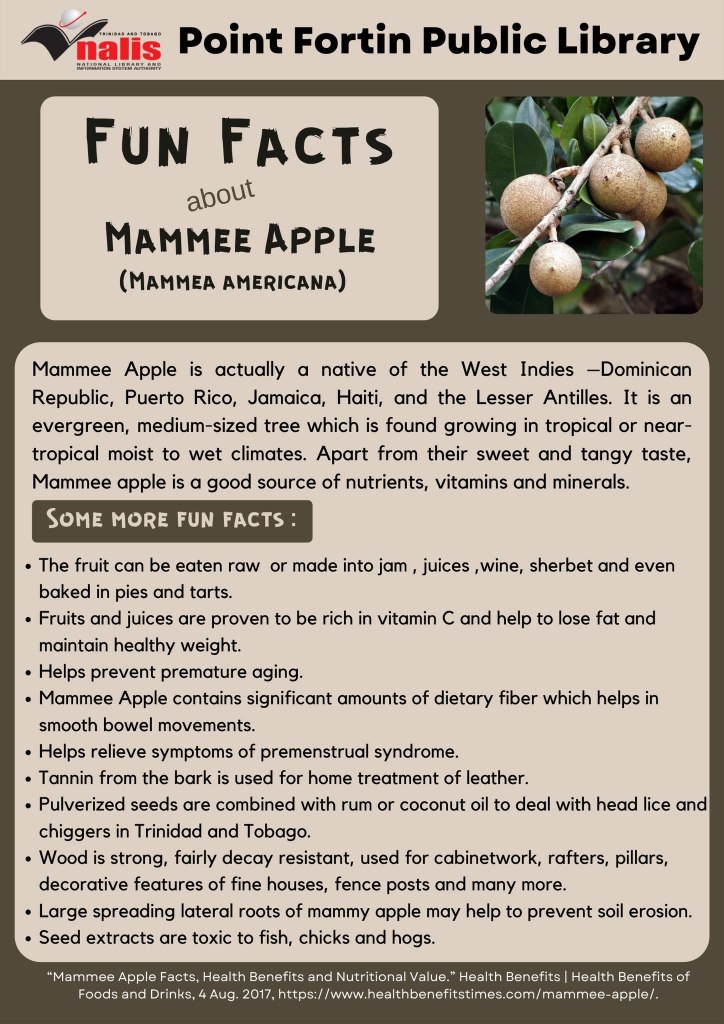

Now mamey is an interesting name. It is also linked to an evergreen species of tree (or its edible fruit), Mammea americana. This is only a linguistic thing though. The fruit is not the same and the two could not easily be confused.

Mammea americana

Pouteria – a large genus consisting of around 235 species of (primarily) tropical American timber trees (1) (in the family Sapotaceae) with several varieties known for their edible fruit. Pouteria is derived from the Galibi (2) name for this type of tree, “pourama-pouteri”.

- The Pouteria species yields hard, heavy, resilient wood which can be used as firewood and timber but is also particularly well suited for outdoor and naval construction, such as dock pilings, decking, etc. Some species, such as abiu (P. caimito), are considered to be shipworm resistant.

- It was more difficult (and confusing) finding info on this group. The Galibi are indigenous to areas of Brazil, French Guiana and Suriname (but it is not that simple)

Also called the mamey sapote

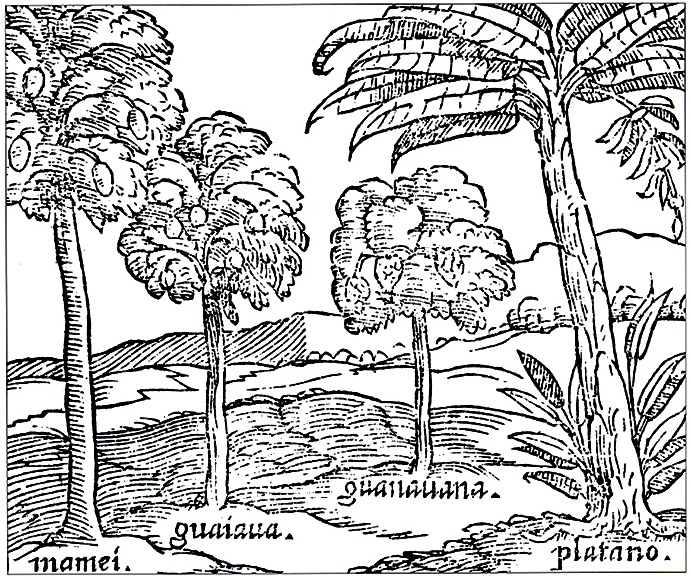

Mamey derives from the Taino (1) word “mamei”. The word sapote is derived from the Nahuatl botanical terminology “tzapotl” (or in this case “tezontzapotl” – more on this in a bit), a general term applied to all soft and sweet (edible) fruits.

- The Taino are an indigenous people of the Caribbean who (at the time of European contact in the 15th Century) were the principal inhabitants of most of what is now The Bahamas, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and the northern Lesser Antilles.

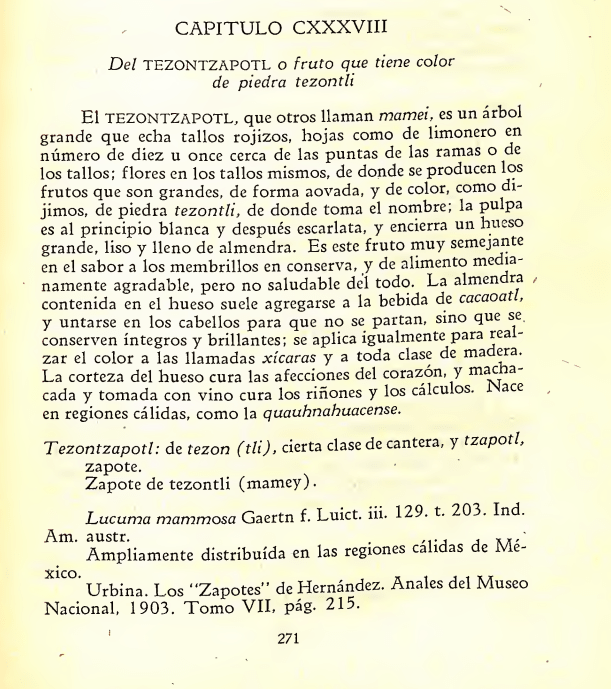

As previously mentioned, one name for this fruit (and this specific fruit) is tezontzapotl. This was the name with which the protobotanist Francisco Hernandez described the plant in his book, Historia de las plantas de Nueva España. For more on this man and his books see (1)

First, en español……..

Del TEZONTZAPOTL o fruto que tiene color de piedra tezontli

El TEZONTZAPOTL, que otros llaman mamei, es un árbol grande que echa tallos rojizos, hojas como de limonero en número de diez u once cerca de las puntas de las ramas o de los tallos; flores en los tallos mismos, de donde se producen los frutos que son grandes, de forma aovada, y de color, como dijimos, de piedra tezontli, de donde toma el nombre; la pulpa es al principio blanca y después escarlata, y encierra un hueso grande, liso y lleno de almendra. Es este fruto muy semejante en el sabor a los membrillos en conserva, y de alimento me ianamente agradable, pero no saludable del todo. La almen ra contenida en el hueso suele agregarse a la bebida de cacaoat , y untarse en los cabellos para que no se partan, sino que se conserven íntegros y brillantes; se aplica igualmente para reazar el color a las llamadas xícaras y a toda clase de ma era. La corteza del hueso cura las afecciones del corazón, y mac a cada y tomada con vino cura los riñones y los cálculos. Ace en regiones cálidas, como la quauhnahuacense.

Tezontzapotl: de tezon (tli), cierta clase de cantera, y tzapotl, zapote.

Zapote de tezontli (mamey).

Lucuma mammosa Gaertn f. Luict. iii. 129. t. 203. Ind. Am. austr. . ,rj ,

Ampliamente distribuida en las regiones calidas de Mexico.

Of the Tezontzapotl or Fruit That Has the colour of a Tezontli Stone

The Tezontzapotl, which others call mamei, is a large tree that grows reddish stems, with leaves like those of a lemon tree, ten or eleven in number near the tips of the branches or stems; flowers grow on the stems themselves, from which the fruits are produced, which are large, ovate in shape, and coloured, as we said, like a tezontli stone, from which it takes its name. The pulp is at first white and later scarlet, and encloses a large, smooth, almond-shaped pit. This fruit is very similar in flavour to preserved quinces (1), and is moderately palatable, but not entirely healthy. The almond contained in the stone is usually added to the cacao drink and spread on the hair so that it does not break, but remains intact and shiny; it is also used to enhance the colour of the so-called xicaras and all kinds of materials.

The bark of the pit cures heart conditions, and macerated and taken with wine, it cures kidney stones. It occurs in warm regions, such as the Quauhnahuacense.

Tezontzapotl: from tezon (tli), a certain type of quarry, and tzapotl, sapote.

Sapote from tezontli (mamey).

Lucuma mammosa Gaertn f. Luict. iii. 129. t. 203. Ind. Am. austr.

Widely distributed in the warm regions of Mexico City.

- membrillos en conserva (preserved quinces) a species of fruit Cydonia oblonga. This fruit is a relative of the apple and pear. As a fresh fruit it is rock hard, extremely astringent and virtually inedible. When cooked slowly (and with plenty of sugar) it deepens in colour to a deep pink/red and has an exquisite aroma.

The mamey sapote is a species of tree native to southern Mexico and Central America. The tree occurs naturally at low elevations. It is cultivated up to 600 m and occasionally found up to 1500 m. It is cultivated throughout Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean, as well as Florida and parts of South America. In Mexico the mamey is predominately grown in the states of Veracruz, Guerrero, Chiapas, Morelos, Yucatan and Tabasco.

Botanically speaking, the fruit is classed as a berry.

In Mexico, the harvest time is usually from March to July, although the fruit can be found in the market throughout the year.

Flesh colour is the main criterion for timing of harvest. A method commonly used is to scratch lightly the surface of the rough fruit peel with the fingernail. A turning colour from yellow to light pink-salmon of the pulp indicates that fruit is ready to harvest. For commercial purposes, fruit is usually harvested at this stage. The best eating quality is when fruit flesh is reddish.

As for the flavour of the fruit? I think Willy Wonka might even have trouble with this one.

- The pulp closely resembles that of papaya or mango, featuring a soft and creamy texture. Its flavor is reminiscent of sweet pumpkin with a hint of vanilla, and tastes almost as if it were blended with peach

https://mexiconewsdaily.com/food/taste-of-mexico-mamey/

- The flavor is a combination of sweet potato and pumpkin with undertones of almond, chocolate, honey and vanilla.

https://yucatanmagazine.com/mamey-on-the-menu-learn-about-yucatans-healthy-fruit/

- the orange-fleshed fruit has a taste that some compare to a brown sugar-covered sweet potato, with notes of pumpkin, caramel and cantaloupe.

https://foodprint.org/real-food/mamey-sapote/

- The flesh bears a complex sweet and savory flavor, containing subtle notes of vanilla, nutmeg, apricots, and root beer mixed with honeyed pumpkin, squash, and sweet potato nuances.

https://specialtyproduce.com/produce/Mamey_Sapote_109.php

- has a texture like that of a papaya, tastes like sweet vanilla papaya and pear, or a mix of sweet potato, pumpkin, honey, prune, peach, apricot, cantaloupe, cherry, and almond

https://www.mejcreations.com/workszoom/4764821/in-the-heart-of-mexico-mamey-sapote#/

Pumpkin seems to be the only common factor.

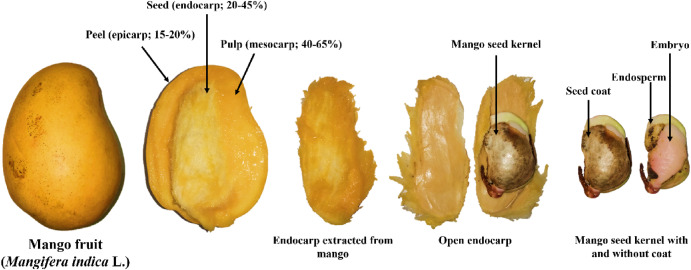

I won’t go into the fruit much as it is the seed of the fruit that is the focus here. This seed, also called “hueso de mamey” or, the mamey bone can be fairly large (think mango) but, unlike the mango which has a fibrous coating, the mamey seed has a hard and smooth outer shell.

Mango seed for comparison.

To utilise the seed you crack open this outer shell and remove the inner kernel (often called an almond) and which has a soft texture and a slightly bitter taste. Its scent is most often reported as being like almonds. This scent is likely due to the presence of amygdalyn. (I will go into more detail on this in the Medicinal Uses section at the bottom of the Post)

One Specialty Produce website notes that “The seeds are toxic and inedible when raw, but they can be treated through an extensive process to remove the toxins for culinary use.” (I will go into more detail on this in the Medicinal Uses section at the bottom of the Post)

Various instructions include…

- after leaving it in water with lime – something very similar to nixtamalizing corn – rinse it to remove the drool (baba)

- the pixtle is left in soak for two days to turn it into a paste

- It doesn’t take much more to cook with the bone of the mamey than removing the peel and scrubbing the pulp. For longer preparations, let it soak for at least one day; to take advantage of its aroma, just boil and scrape what will then be a pulp

- it is dried, then soaked in water, cooked twice, and ground to form a paste

The most complex description can be found in the book, “Mexico, a Culinary Odyssey” by Diana Kennedy. Diana was a combination home cook, historian and ethnographer who fell in love with the regional cooking of Mexico and spent years travelling the country cataloguing the use of unique regional herbs/food/recipes/styles. She has been credited with recording dishes unique to the heritage of mexico that might have otherwise disappeared into memory if not for her efforts. In this book Diana recounts the steps that Mrs. Evelina, a traditional cook follows to transform pixtle:

When the mamey season arrives between the months of February and May, the perfectly ripe fruits should be selected and opened, their pulp removed, and the seeds extracted. They should then be thoroughly rinsed and placed in a clay pot filled with water and a handful of ash, where they will be left to boil gently over a wood fire for two days and nights (although the exact point to know if they are ripe is when they no longer have any slime). After this time, the pixtles are removed from the water, rinsed, and any remaining slimy or sticky layer is scraped off. They are then boiled again in the clay pot, but this time with a variety of 13 different herbs and leaves instead of ash. After boiling the seeds for another two days and nights, they become so soft that they are cut into wedge-shaped pieces 5 cm long by 1 cm wide. The pieces are then strung together with thread to form “necklaces” that are hung over a brazier to smoke and dry in the sun. At this point, the heat causes their natural oils to emerge and paint their surface with irregular white spots.

A relatively complex set of instructions. And these are just a pre-preparation. We are making the ingredient safe to use. Is it really this dangerous? The Agua de Hueso de Mamey recipe below would seem to refute this.

While we are on the subject of “huesos” (bones)

The word pixtle comes from the Nahuatl pitztli, meaning bone or seed. This ingredient, widely used in Mexican cuisine since pre-Hispanic times, is the mamey “bone” and, linguistically speaking, goes some way in explaining this “boneless sandia”

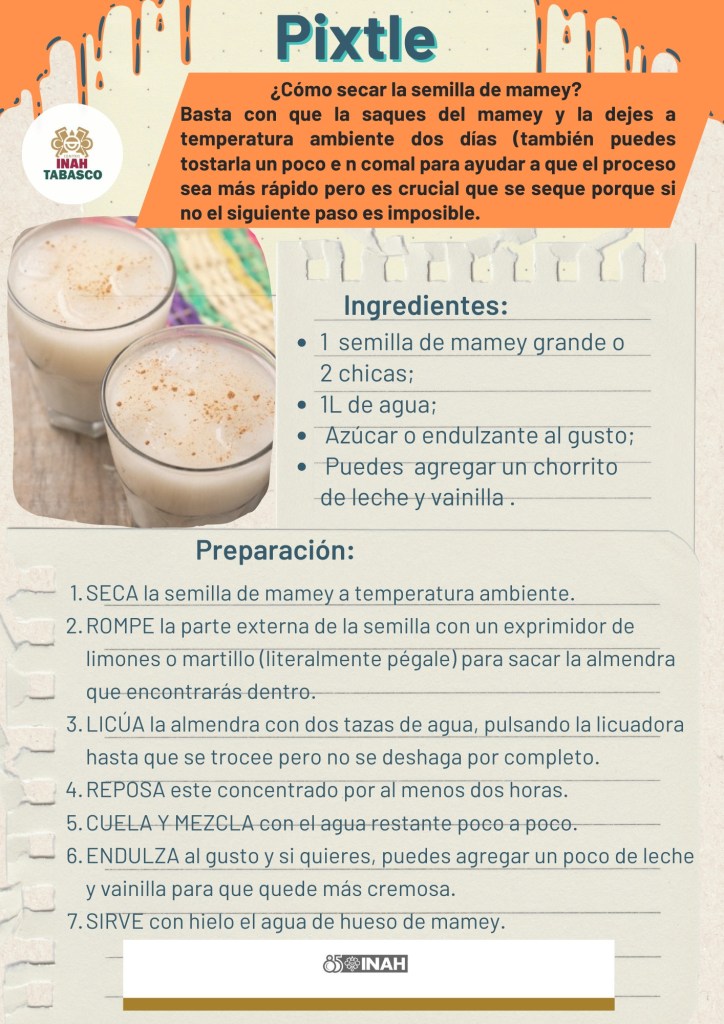

Agua de hueso de mamey (mamey “stone” water) (via Kiwilimon)

Ingredients

- 1 mamey bone (hueso de mamey)

- 1/4 cup sugar

- 3 cups of water

- almonds to taste, sliced, for decoration

Method

- Break the mamey stone and remove the shell.

- Blend the bone, sugar and water for 5 minutes.

- Let it rest for 3 hours.

- Strain the fresh water and pour it into a pitcher with ice.

Gastrolab expands on this a little in their recipe….

Here they refer to the inner part of the seed as the almendra or the “almond”

Agua del hueso de mamey

Ingredients

- 1 mamey stone

- 1 litre of water

- Sugar to taste

Method

- Place the water in a pitcher and sweeten to taste. The recommendation is to use 150 grams of sugar per liter of water, but it depends on your taste, and you can adjust the sweetness later if you wish.

- Carefully cover the mamey stone with a cloth and tap it against a firm surface to break the shell and release the almond inside.

- Using a food grater, completely grate the almond from the mamey stone. Place all the grated almonds in the sweetened water and refrigerate for 3 hours to allow them to begin to release their full flavor.

- Strain the mixture through a piece of woven cotton. Check the sweetness of the water and, if necessary, add a little more sugar to taste. Serve in glasses with a couple of ice cubes.

- Start by drying the mamey seed at room temperature

- Once it is dry, remove the outer part of the seed to get the inner part that looks like an almond, you can do this by hitting it or pressing it

- Place the almond in a blender along with 2 cups of water and blend lightly; do not blend completely.

- Let the concentrate sit for two hours to extract all the flavor and aroma.

- Strain and mix the extract with the remaining water.

- Add sugar to taste, mix well, serve and enjoy.

Tip: If you want it to be creamier, you can add a little evaporated milk.

Tip 2: Do not add all the concentrate, add it little by little, because if you add it all it could taste like soap.

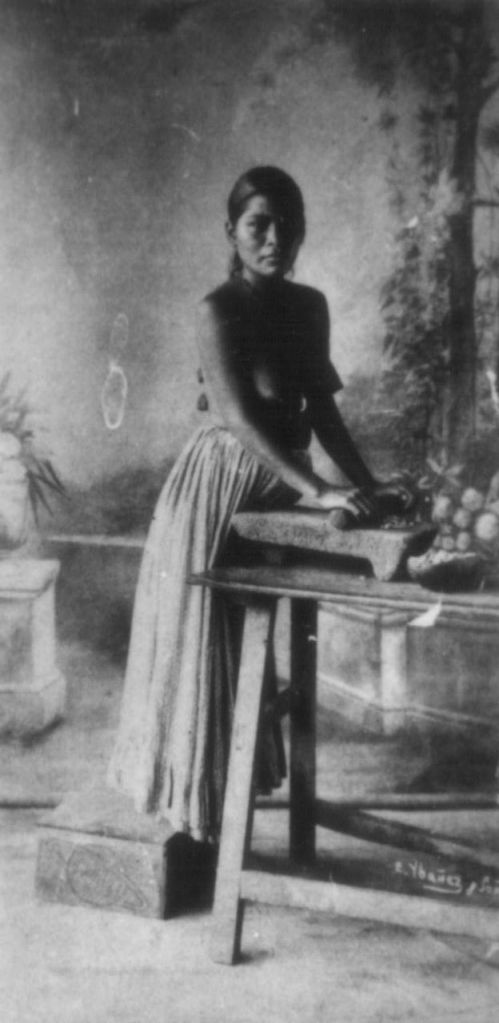

Pozol With Pixte (1) is a drink of the Chontal Maya people (2)

- the author notes that “Pixte. The seed of the sapote, red sapote or tezonzapote, improperly also called mamey or red mamey, is an elongated, ellipsoidal nut enclosed in a smooth, lustrous, shiny, dark red testa, with a frosted, opaque ventral face; ending in sharp points at both ends”

- The Chontal Maya are a Maya people of the Mexican state of Tabasco.

Ingredients

- 1 kg of corn (preferably purple or black)

- 6 pixte

- 25 g of cal (lime for nixtamalization)

Method

- The first step of this recipe requires you to nixtamalize your corn. Water quantities are not given but ensure your corn is well covered by water, add the cal and ensure that it is well mixed. Boil.

- After a few minutes of boiling, remove a kernel and rub it with your fingers to see if the skin can be easily removed. When this happens, remove the corn from the heat, drain it and wash it several times in fresh water until the kernels are completely clean. Add more water to the corn and return it to the heat until the kernels are soft.

- Care must be taken to ensure that the corn is not acheguado, meaning that it is not too soft. Corn that has burst due to cooking and the action of lime is called chegua.

- The pixte is toasted and ground, then mixed with the dough until it has a uniform color.

- Take a portion of this dough and whisk it by hand or blend it with very cold water. Serve it in a jicara.

This recipe introduced me to two new cooking terms (specific to Rabasco it seems)

Sorry, sorry. Tabasco.

CHEGUA: name given (in Tabasco) to maiz that has been cooked in cal (nixtamalised) and has burst during the cooking process.

ACHEGUADO: In Mexico, the name given to corn when it is too soft due to overcooking.

Pozol blends from Tabasco

The image above (from Tabasco) shows 2 varieties of Pozol. These blends, made from corn processed with cocoa differ in the manner in which the corn was cooked. The Pozole at the top is corn sancochado, the Pozole below is nixtamalized corn which is known as “chegua” (referring to maiz that has been cooked longer and until it is much softer that corn used to make masa for tortillas). Boiled corn pozol (maíz sancochado) (1) is strained with the help of a sieve, since the grain’s husk remains in the mill…(Macuspana Aquiles Serdan-San Fernando)

- Corn cooked in water (without lime/cal) and then left to rest until it cools. Rinsed, strained, and finely ground in a mill. This base can be used to make various dishes, including strained tamales (tamales colados)

INAH Tabasco

In April of 2024 Victor, from FLAAR Mesoamerica (1), writes of travelling to the beautiful mountains of Senahú (2) to visit the Chipemech community to document the preparation of a cacao like drink made using the seeds of the mamey sapote.

- FLAAR Mesoamerica is a civil, non-profit, independent association, with educational and research purposes, which currently develops projects to promote the conservation of the environment and the cultural heritage of the Mesoamerica region. Their Vision is “To be the leading institution of the Mesoamerican region in the documentation, study, and dissemination of the diversity of native species and the Pre-Columbian heritage”

- Senahú is a town and municipality of the Department of Alta Verapaz in the Republic of Guatemala.

The mamey sapote fruits are harvested and the seeds are extracted and their hard skins removed.

The soft core of the seeds are cut into smaller pieces and placed in a clay pot with water to simmer for 3 days.

The seeds are drained, allowed to dry a little and then toasted on a comal

The toasted seeds are then ground into a paste on the metate. This dough is then diluted (1 handful per litre of water), sweetened with sugar to ones liking and consumed as a watery, atole like chocolate substitute

Beyond bebidas.

In Puebla, roasted and ground cacao beans are mixed with cacao to create a foamier chocolate. In Oaxaca, it’s used for téjate (1) —it’s the pixtle that gives this drink its distinctive foamy consistency—and in Tabasco, it’s used to enrich pozol and sour atole. In Guerrero, it’s used for fiesta atole (atole de fiesta), a white atole made from corn to which ground pixtle is added. In the Totonacapan region of Veracruz, pixtle is grated and left to dry in the sun, then ground with water and green chilies to make the sauce for “enchiladas de zapote mamey” and in Guerrero, it is added freshly grated or dried and toasted to festive atole to give it more flavour.

- for more information on tejate see…..

- Mexican Cooking Equipment : The Molinillo

- A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Diet

- A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Appendix 2 : Chocolate Drinks

In the Sierra de Puebla the mamey bone is used to make pixtamales, a very traditional type of tamale customary in San José Miahuatlán, Tehuacán, Puebla. A tamale of pre-Hispanic and ritual origin, it was formerly prepared for the Day of the Dead, a common offering in altars (ofrendas) for el Día de muertos, although today it can be made on any date.

First the pixtle is boiled, smoked, and sliced and dried. This is how you’ll find it at the mercado (unless you wish to complete this first process yourself) .

To make them, dried mamey pits or pixtles are soaked in water (for around 2 days) and then cooked twice until they crumble (although the word used here was “dissolve”) and can be easily made into a paste. The pixtle paste is seasoned with powdered Hoja Santa leaves and ancho chile. The seasoned pixtle is then spread onto a layer of corn masa (prepared for tamales por supuesto), wrapped in fresh long corn stalk leaves called “hoja de milpa” and baked in an earth oven. It is It was once prepared with a fruit known as tliyapo.

Enchiladas de pixtle

Ingredients

- 20 tortillas

- 3 (dried and ground) pixtle

- 3 green chilies

- 4 tbsp chopped onion

- 1 lt of water

- 2 tbsp butter

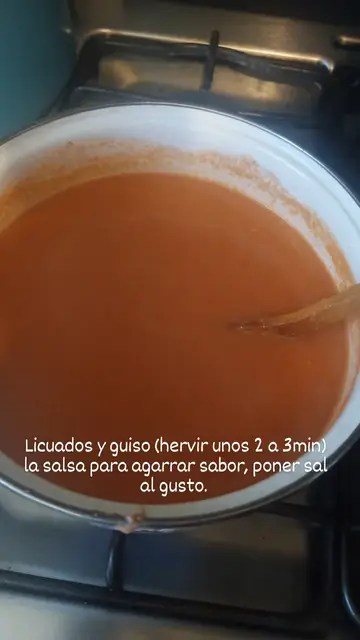

- Toast the pixtle pieces until they release their aroma. Grind them with the water and chilies.

- Sauté the onion in the butter and add the sauce. If necessary, add more water to thicken it.

- Heat the tortillas, dip them in the sauce and pour them over the tortillas before serving.

Latino Detroit

NMScook from Zacatecas, Mexico, a contributor to the global cooking community via cookpad, gives us a Huasteca recipe for enchiladas de pixtle which he describes as having a “delicate and sophisticated” flavour

Ingredients: 6 servings

- 2 mamey seeds (pixtle)

- 2 serrano chiles

- 4 roma tomatoes

- 100 ml water

- Salt to taste

- 1 small/medium white onion (3/4 cup roughly chopped onion)

- 2 small or 1 large garlic clove

To construct the enchiladas

- 1 to 1/2 kg corn tortilla

- Chicken, cheese, or any filling you want to use

Method

Peel the seeds (pixtle), grate them, and leave to dry (in the recipe NMScook posts he recommends you dry them “as he does” and provides an image. Pixtle, grated to the texture of what looks to be shredded coconut, placed on his mothers best plate and placed in full sun in the patio garden. No length of time is given for the drying (but his photo does say “the next day” – al siguiente dia – so at least 1 day full sun I reckon – I wouldn’t leave it out overnight though)

Char the serranos over an open flame until blistered on all sides and then place in a covered bowl or wrap in a damp teatowel (or do as the author does and wrap them up in a sandwich bag) and allow them to sweat for 5 minutes before scraping off the skin.

Clean the tomatoes and add them to a blender with the garlic, onion, and salt. Blend until smooth.

Add the peeled serrano chiles (no mention of whether or not you should remove the seeds) and the pixtle to the blender. Blend until smooth.

Place a few tablespoons of oil in a pan and heat over a medium high heat so we can cook the salsa. No mention was made in the recipe as to whether or not the salsa should be strained before cooking. I’m thinking yes as NMScook’s sauce looked very smooth.

Add the salsa to the hot oil and cook until it thickens. You may need to add a little more water if it’s too thick.

Now you make your enchiladas. Warm your tortillas (one at a time) until pliable. Quickly dip it in the pixtle sauce before wrapping your filling of choice. Repeat

NMSCook recommends shredded chicken, but (like the infinite possibilities of any good enchilada) you can use just cheese or another filling.

Time to enchilarse.

Dessert (Postres)

Pan de muerto relleno de crema de pixtle y compota de guayaba.

Pan de muerto filled with pixtle cream and guava compote.

Located in the heart of Mexico City’s historic Reforma avenue, the Sofitel Mexico City have on their menu a postre of pan de Muerto filled with a pixtle cream and guava compote (1). This too could be considered delicate and sophisticated. They even supply the recipe if you wish to give it a crack yourself

- They also offer – pan de muerto de chocolate con costra de ceniza de totomoxtle y relleno de crema de chocolate de metate, pan de muerto de calabaza de castilla con costra de semilla de calabaza y relleno de crema de chocolate Caramelia : chocolate bread of the dead with a totomoxtle ash crust and metate chocolate cream filling, Castilian pumpkin bread of the dead with a pumpkin seed crust and Caramelia chocolate cream filling

First make your Pan de Muerto

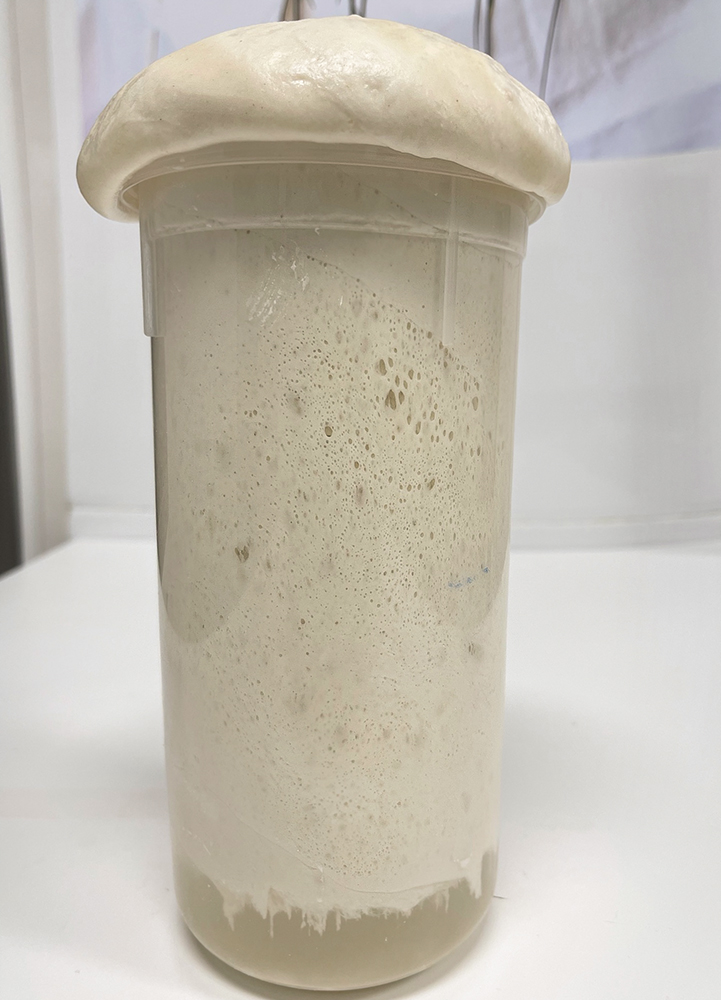

The chefs in this kitchen do not fuck around. To make the dough for the Pan de Muerto they use masa madre sólida (or a live sourdough)

Ingredients

- 1 kg flour

- 20 g salt

- 200 ml milk

- 390 g butter

- 40 g fresh yeast

- 200 g sourdough starter

- 180 g sugar

- 450 g egg (5 or 6 large eggs)

- 20 g lemon zest

- 20 g orange zest

- 3 ml orange blossom essence

- 3 ml orange essence

Method

- Mix yeast with water and a teaspoon of sugar, making sure there are no lumps and that the mixture is smooth.

- In a separate bowl, mix the flour, the remaining sugar, salt, eggs, sourdough starter, orange blossom essence, orange essence, lemon zest, and orange zest. Stir in the yeast and orange mixture.

- Add the cubed butter at room temperature and knead the mixture until a smooth dough forms. Place the dough in a container and cover.

- Let the dough rest for one hour until it doubles in volume, then let the dough rest for four hours in the refrigerator.

- Separate ⅓ of the dough to make canillas and form into balls of approximately a fist’s size with the rest.

- Form the reserved dough into skeins and a small ball, then add them to the balls you’ve created to make the pan de muerto shape. Brush the bread with egg and let it rest for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Preheat the oven to 180° and then bake for 20 minutes.

- Remove the bread and let it rest for 20 minutes.

- Spread the bread with softened butter and sprinkle with sugar.

- Serve and enjoy, or fill with the pixtle cream and guava

Pixtle Cream Recipe

Ingredients

- 150 g 35% cream

- 10 g inverted sugar (azúcar invertido) or honey

- 10 g glucose (more on this ingredient in a bit)

- 290 g Caramelia Valrhona milk chocolate

- 1 grated pixtle seed

Preparation

- Heat the cream with the inverted sugar and the grated pixtle seed.

- Pour over the chocolate, let it sit for two minutes and emulsify.

- Add the cold cream and mix, refrigerate.

- Whip the cream in a mixer at medium speed for approximately five minutes and pour into a piping bag.

Guava Compote

Ingredients

- 390 g guava puree

- 110 g guava chunks

- 80 g refined sugar

- 6 g pectin NH

Preparation

- Heat the guava puree and guava chunks in a pot over medium heat.

- Add the sugar and pectin, bring to a boil and remove from heat.

- Let it rest and pour when cold.

New ingredient : Pectin NH

From the experts “Pectin and Pectin NH (Non-Heat-Reversible Pectin) are both substances used in the culinary world, particularly in the pastry industry, for thickening and setting purposes. Pectin, a naturally occurring carbohydrate found in fruits, plays a crucial role in the process of jelly and jam making. Extracted primarily from citrus fruits, apples, and berries, pectin acts as a gelling agent. Pectin NH: This is a modified form of pectin that undergoes specific treatment to make it non-heat-reversible. It is derived from citrus peels. Unlike regular pectin, it stands out for its ability to gel without extensive boiling, which helps preserve the fresh flavors and vibrant colors of fruit ingredients. Can be melted and set multiple times without losing its gelling ability. It sets faster and more easily than regular pectin.”

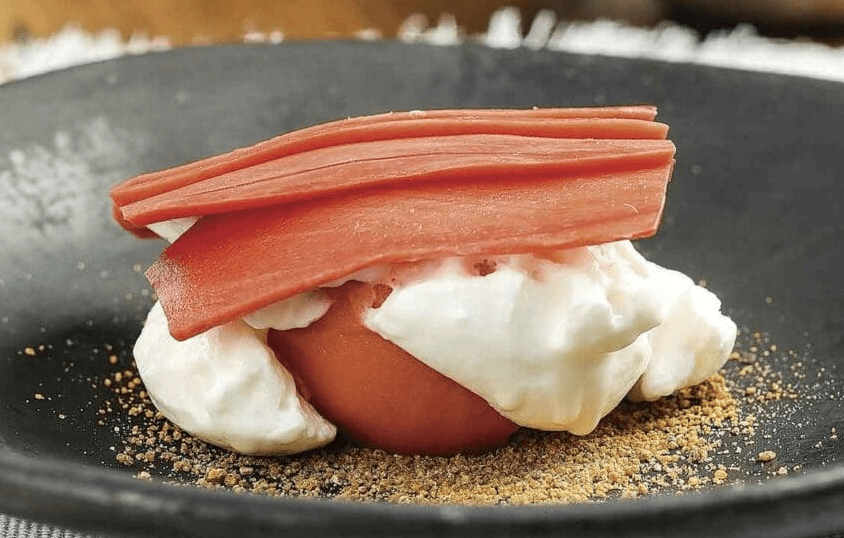

Even though the above recipe seemed a little more work than most would like to put in, the next recipe, from Food and Travel Mexico, is a sophisticated and technical recipe that uses both techniques, tools, and ingredients that may lay beyond the ken of the average cocinero. If you have ever dreamed of Masterchef then I recommend trying this recipe. It is a delicate and classy dessert (several iterations of which are shown in the images below) and demonstrates the clever utilisation of a single mamey, from “nose to tail” as it were. This is a beautiful example of Mexico’s culture plated artfully as a sweet, sweet postre.

Mamey, pixtle y taxcalate

Ingredients

- 1 mamey

For the taxcalate crumbs (migas de taxcalate)

- 20 g of flour

- 30 g of taxcalate

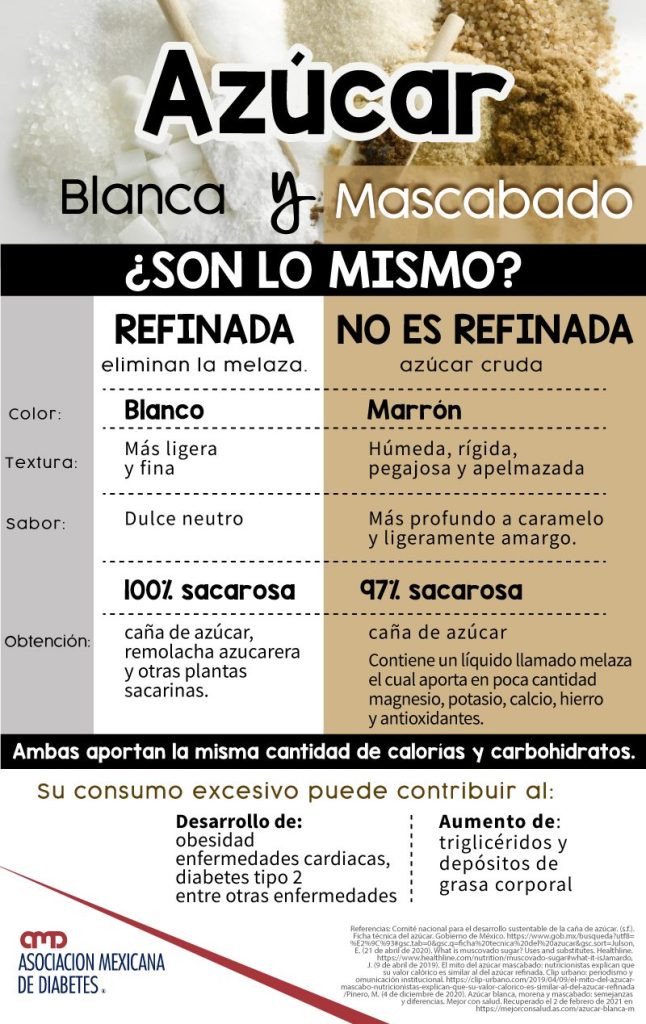

- 14 g of brown sugar (azúcar mascabado)

- 1 pinch of ground cinnamon

- 38g unsalted butter, creamed

Azúcar mascabado or Muscovado sugar is unrefined or lightly refined sugar. To make it, the juice is extracted from sugarcane and evaporated until a dry residue is obtained, which, when ground, achieves a flavor comparable to caramel. The main difference between this sugar and granulated sugars, such as Demerara sugar or brown sugar, is the moisture content.

For the pixtle foam (espuma de pixtle)

- 1 sheet of gelatin

- 75 ml of milk

- 180 g whipping cream

- 26 g of pixtle (mamey seed), grated

- 12 g of sugar

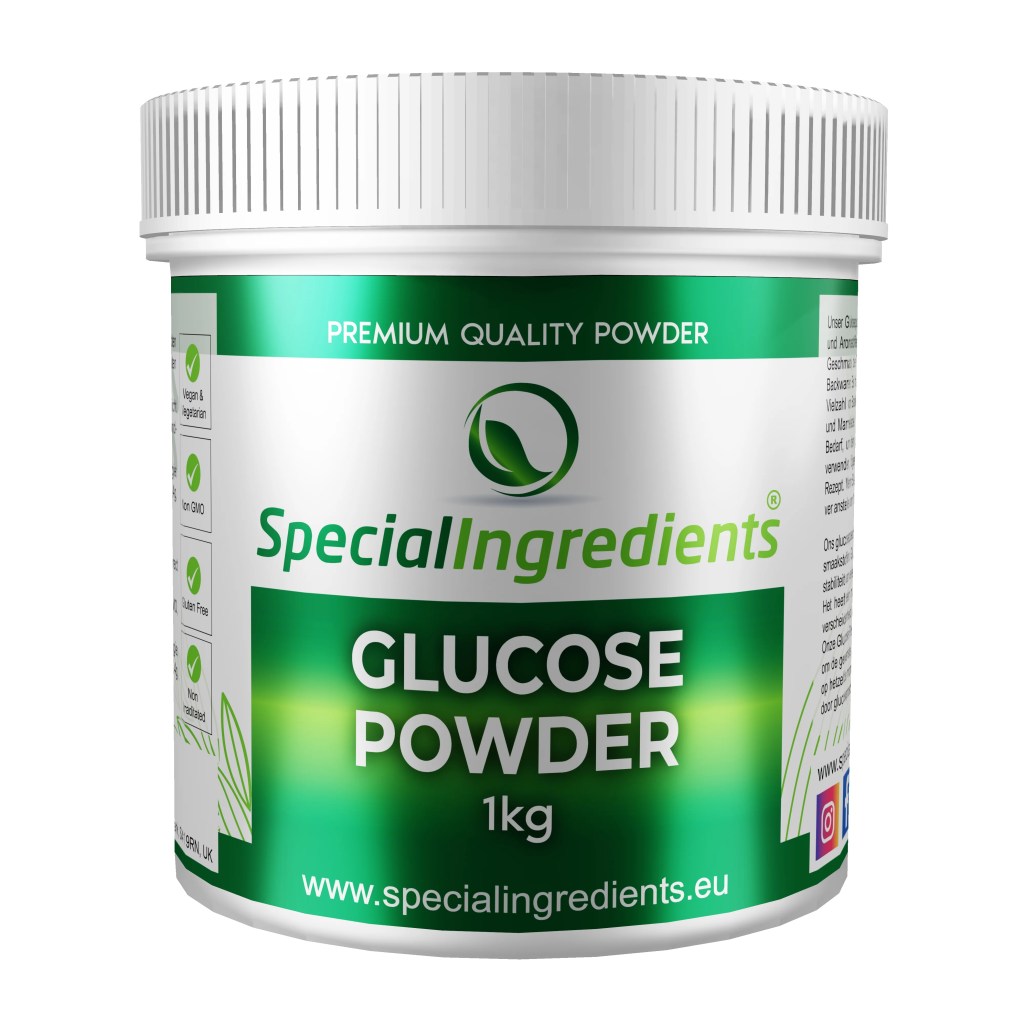

- 7 g of glucose powder (available at baking supply stores)

For the mamey sorbet (sorbete de mamey)

- 390 g of mamey pulp

- 100 g of refined sugar

- 65 g of glucose

- 3 g of ice cream stabilizer

- To make the taxcalate crumbs, mix all the dry ingredients and a pinch of salt in a bowl. Mix in the butter with your hands. Spread on a baking sheet covered with parchment paper and freeze for 2 hours.

- Bake at 180°C for 24 minutes, stirring the crumbs with a spatula every 6 minutes to break up any crumbs, until the crumbs are evenly toasted. Remove from the oven and let cool to room temperature. Set aside.

- For the pixtle foam, hydrate the gelatin in cold water. Meanwhile, in a saucepan, place the milk, cream, and pixtle. Heat to 60°C and let it infuse off the heat for 15 minutes. Blend, strain, and reheat in a saucepan over the heat. Add the sugar and glucose. Bring to 60°C and remove from the heat again. Lightly squeeze the gelatin sheet and dissolve it in the mixture. Strain once more and transfer to the siphon. Close tightly and add the nitrogen charge. Shake and refrigerate.

- For the mamey sorbet, blend the mamey pulp with 140 ml of water until a light, smooth puree forms. Separately, heat the sugar, glucose, and 100 ml of water in a saucepan. When the mixture reaches 40°C, add the stabilizer and bring to 85°C. Place the saucepan inside a container with ice and cool to 4°C. Add the mamey puree and refrigerate overnight. Blend and put in an ice cream machine. Freeze.

- To serve, cut the mamey into very thin slices, similar to carpaccio. Place a few crumbs in the center of the plate, then serve the mamey sorbet on top. Cover with the pixtle foam and arrange the mamey slices on top. Finish with more crumbs.

Taxcalate (alternative spelling tascalate, tazcalate) is a chocolate drink made from a mixture of roasted maize, roasted cocoa bean, ground pine nuts, achiote and sugar or panela, very common in the Mexican state of Chiapas. For more information on tascalate see A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Appendix 2 : Chocolate Drinks

In the recipe for Pan de muerto relleno de crema de pixtle y compota de guayaba, and the recipe above, several varieties of (more or less) the same sweetener are used. These are glucose syrup (often just noted as being “glucose”), glucose powder and invert sugar. These are all effective sweeteners but they are being primarily used here to control the texture and smoothness of the final element (i.e. cream, foam or ice cream/sorbet)

The “sorbete” in the above recipe also uses another uncommon pantry item, that being the ice cream stabiliser. The most common ice cream stabilisers are guar gum, cellulose gum and carob bean gum. They are used to delay the appearance of and reduce the size of ice crystals forming in the mix which increases the smoothness and texture (the mouthfeel) of the ice cream. From a technical (and commercial) point of view they also help to achieve good “overrun”. Overrun is the increase in ice cream’s volume due to the incorporation of air during churning. Air is considered the final ingredient. It is light and free and the more you can get into your ice cream the more you can produce from the same quantity of base ingredients. There is a limit to this though. The ideal overrun in ice cream is considered to be between 30 and 40%. To achieve this percentage (in addition to adding air during churning) the selection of emulsifiers, and the balance of proteins, fats, water, and sugars in the mix are crucial, and this is where ice cream stabilisers come into the mix.

The mamey bone also has medicinal uses.

Medicinal use of pixtle

The seed and leaves are used in a poultice for wounds and sores. The pulverized seed mixed with aceite de rincino (caster oil) (sic) is used in treatments for alopecia. For bronchitis or other respiratory ailments, the seed is toasted first, then ground into a powder, and added to a tea. To treat acne, the powdered seed is mixed with the juice from one limón and applied to breakouts. Wash with warm water after 30 minutes. For liver ailments, the pixtle is grated into a cup of boiled water and drunk daily for two weeks. The fruit is prescribed for gastritis and diarrhoea or used topically for skin treatments.

The fruit has anti-amyloidogenic and anti-tumorigenic properties. It contains carotenoids which give it its distinctive colour. It is also anti-inflammatory, antifungal, and antioxidant. The leaves demonstrate antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-cancer activities. https://survivingmexico.com/tag/pixtle/

Home remedies using pixtle include……

For hair loss: Boil the pixtle and let it sit for a few minutes. When it has cooled slightly, massage it into your scalp. Repeat twice a day for a month. Another remedy is to mix a powdered pixtle with 300 g of castor oil. Apply with gentle massages all over your scalp. Do this once a week.

Mamey seed to refresh the kidneys: Grate a pixtle into a powder and pour it into a glass of boiled water. Let it cool and drink it once a day for two weeks.

For pimples: Grate the mamey seed and mix it with the juice of 1 lemon until it forms a cream. Apply to spots and blackheads and let it sit for 30 minutes. Rinse with warm water and repeat twice a week.

Sapote seed Oil is a light, non-greasy, vitamin-rich oil that helps balance sebum production – which can help those with excessively oily, or excessively dry scalps. The oil, described as having “a mild, pleasant taste and almond-like odour” (Jamieson & McKinney 1931) (1) is extracted from the seed kernel (2). This oil, also known as sapuyul or sapayulo oil, even though said to be edible is difficult to source as an edible oil. The primary use of the oil seems to be the pharmaceutical/cosmetics industry where it is used in soaps and a number of hair and scalp treatments. Primarily used to prevent hair loss (Canales 1946) (Phillips et al 1994) the oil is massaged into the scalp. Study has suggested that the oil does not stimulate hair growth but addresses skin conditions on the scalp (seborrheic dermatitis in particular) which can cause hair loss. The oil is used in topical skin creams for similar skin healing purposes (Alia-Tejacal et al., 2007). You can also make a crude oil extraction of the seed kernels yourself by pulverising 2 or 3 mamey bone kernels and macerating them in 300g of castor oil. This paste can then be applied topically to the scalp (or any other skin condition). The seed residue that remains after the oil has been cold pressed from it can also be applied as a poultice to painful skin conditions. Cosmetic companies also note that the oil can protect the skin and help restore it from ultraviolet light damage.

- even after having been held in cold storage for eight years

- The oil is usually extracted through a “cold pressing” process although it can also be obtained via aqueous enzymatic extraction or supercritical CO2 extraction. Oils obtained via all 3 methods have been studied for various uses.

This oil, also called zapoyola, was used by artisans to fix paintings on gourds and other handicrafts (1)(Almeyda & Franklin 1976). Pouteria oil, particularly mamey sapote oil, can be used as a wood finish, similar to other drying oils like tung oil or walnut oil. It can penetrate the wood, providing a protective layer while enhancing the natural grain and colour.

- this is a very common and oft repeated reference. I have been unable to locate its source.

Other Traditional indigenous medicinal practices employ the oil from the mamey sapote seed to treat muscle pain (Tacias-Pascacio et al 2021), coronary, rheumatic and kidney problems (1) (Solís-Fuentes 2015) and as a sedative analgesic for eye and ear pain (Morton 1987)(Morera 1994). A seed infusion is used as an eyewash in Cuba. In Mexico, the pulverized seed coat is reported to be a remedy for coronary trouble and, taken with wine, is said to be helpful against kidney stones and rheumatism.

- seed oil also reportedly has diuretic effects

A brief look at the medicinal uses of other parts of the tree

The bark is bitter and astringent and contains lucumin, a cyanogenic glycoside (1). A decoction of the bark is taken as a pectoral. A tea of the bark and leaves is administered in arteriosclerosis and hypertension. The bark as well as the fruits of mamey sapote ooze milky latex that is used therapeutically in the form of an emetic and anthelminthic to eliminate warts as well as treat fungal shin infections.

- Cyanogenic glycosides are compounds that are chemically bound to sugars and release cyanide in the form of hydrogen cyanide (HCN, prussic acid). Under certain conditions, notably in an acid environment (such as the stomach) or through enzymatic action, cyanide can be released into the body. Many plant species can produce cyanide and over 50 cyanogenic glycosides are known.

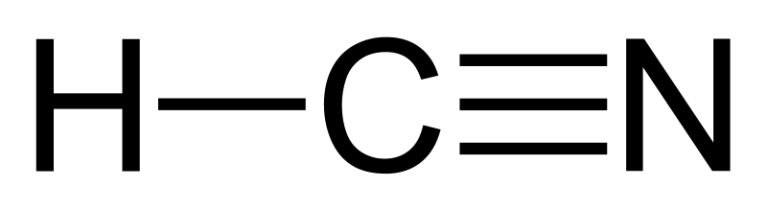

A nitrile is any organic compound having a –CN group, and a triple bond between a carbon atom and a nitrogen atom. The molecular structure of a nitrile is given as R-C≡N

Cyanide is any chemical compound having the cyano (C≡N) group. The cyano group has a carbon atom and a nitrogen atom, which are linked via a triple bond. Thus, the term cyanide may refer to any organic (1) or inorganic (2) compound containing the cyano group. In contrast, the term nitrile refers to any organic compound having a cyano group.

- Organic compounds are any of a large class of chemical compounds in which one or more atoms of carbon are covalently linked to atoms of other elements, most commonly hydrogen, oxygen, or nitrogen. (Farrer & Pecoraro 2003)

- An inorganic compound is defined as a chemical substance that does not contain carbon-hydrogen bonds. These compounds have been utilized for their pharmacological properties and are being explored for their unique properties in treating various diseases (Farrer & Pecoraro 2003)

WARNINGS

It has been previously noted that the pixtle “seeds are toxic and inedible when raw, but they can be treated through an extensive process to remove the toxins for culinary use” and that the almond like scent and flavour of the pixtle is due to amygdalyin. (García et al 2016).

Amygdalin (1) (from Ancient Greek: ἀμυγδαλή amygdalē ‘almond’) is a naturally occurring chemical compound found in many plants, most notably in the seeds (kernels, pips or stones) of apricots, bitter almonds, apples, peaches, cherries and plums, and in the roots of manioc (cassava)

- also called Vitamin B17, amygdalina, puransin, nitriloside, mandelonitrile. Although laetrile is often used synonymously with amygdalin, it is a semi-synthetic compound synthesised from amygdalin by hydrolysis.

Amygdalin is classified as a cyanogenic glycoside, because each amygdalin molecule includes a nitrile group, which can be released as the toxic cyanide anion by the action of a beta-glucosidase. Eating amygdalin will cause it to release cyanide in the human body, and may lead to cyanide poisoning.

Amygdalin is controversial (and I won’t go into it here as it requires at the least a thesis worth of information and background). It can also be known as laetrile or Vitamin B17 (although both are slightly different substances) and is used for improving the health, energy levels and wellbeing of (here is where the controversy arises) cancer patients. In some circles it is touted as a cure for various cancers. This is disputed by almost all of modern Western medical schooling. Laetrile has been banned by the FDA since the 1980s and it is not authorized for sale as a medicinal product in the European Community (Milazzo & Horneber 2015). Laetrile was first used as a cancer treatment in Russia in 1845, and in the United States in the 1920s (PDQ 2022). Through a series of events involving FDA approved in vivo tests which were later cancelled, and then some legal bickering between individual States and the Federal government, laetrile was legalized in more than 20 states during the 1970s. In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court acted to uphold a federal ban on interstate shipment of laetrile which throttled its use and its popularity has greatly diminished. As of 2022 the compound continues to be manufactured and administered as an anticancer therapy, primarily in Mexico, and in some clinics in the United States.

Laetrile can be administered orally as a pill, or it can be given by injection (intravenous or intramuscular). It is commonly given intravenously for a period of time followed by oral maintenance therapy. The incidence of cyanide poisoning is much higher when laetrile is taken orally because intestinal bacteria and some commonly eaten plants contain enzymes (beta-glucosidases) that activate the release of cyanide after laetrile has been ingested. Relatively little breakdown occurs to yield the (hydrogen) cyanide when laetrile is injected. The side effects associated with laetrile toxicity mirror the symptoms of cyanide poisoning, including liver damage, difficulty walking (caused by damaged nerves), fever, coma, and death.

The T.G.A of Australia (1) notes that In humans, the lethal oral dose of HCN is reported to be 0.5–3.5 mg/kg body weight. A level of 0.5 mg/L (approximately 20 micromolar) of cyanide in blood is cited in the literature as a toxicity threshold in humans. A series of poisoning cases are reported from ingestion of preparations containing amygdalin and bitter apricot kernels. In adults, 20 or more kernels were reported to be toxic while the corresponding number in children was five. The Australian Cancer Council states that “the sale of raw apricot kernels was prohibited in Australia and New Zealand in December, 2015”. There was an application (to the T.G.A) in 2020 to have laetrile removed from the Poisons List but it was denied.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration

And just so you know….there is an RDA acceptable level of cyanide

The mean and 97th percentile overall daily intake (1) of HCN (2) have been estimated to be about 46 – 95 and 214 – 372 mcg/person (Rietjens et al 2005) which corresponds to 0.7 – 1.4 and 3.3 – 5.4 mcg/kg bw/day (European Food Safety Authority 2004). The T.G.A notes that “Complete degradation of 1g amygdalin releases 59mg of hydrocyanic acid (5mg amygdalin would be equivalent to 0.3mg HCN)”.

Cyanide “content” of various seeds

- apricot seeds contain 2.92 mg/g HCN

- peach seeds contain 2.60 mg/g HCN

- apple seeds contain only 0.61 mg/g HCN.

Compare that with….

- Cassava root 10 -1120 mg/kg and

- Lima beans (Phaseolus lunatus) at 100 – 3000mg/kg.

These beans are toxic unless cooked. I was not aware of this at the time I was researching these figures. I did know (and was taught during my apprenticeship as a chef) that as few as four or five red kidney beans (Phaseolus vulgaris species) can cause potentially deadly poisoning in children or susceptible adults (3).

- The 97th percentile for daily intake represents the amount of a nutrient that is sufficient to meet the needs of 97 out of 100 healthy individuals. This is often used in reference to the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA), which is the average daily intake level that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97-98%) healthy individuals in a particular life stage and gender group.

- Hydrogen CyaNide

- This type of poisoning is not due to cyanide but phytohaemagglutinins. Phytohaemagglutinin can agglutinate many mammalian red blood cells and interfere with cellular metabolism. Moreover, phytohaemagglutinin is an antinutrient, which can interfere with the absorption of minerals, particularly calcium, iron, phosphorus and zinc. Symptoms of phytohaemagglutinin poisoning include severe stomach-ache, vomiting and diarrhoea.

Now this is where it gets a little ridiculous.

Lets look at cake.

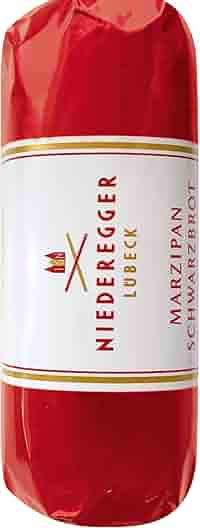

Food products containing relatively high levels of HCN (free and bound) are almonds and/or marzipan-containing confectionery and baked goods, that may contain levels up to 40 mg/kg, with raw marzipan paste containing the highest level of 50 mg HCN (free and bound)/kg

The marzipan coated Prinsesstårta or Swedish Princess cake (Princess Torte)

How many slices of this marzipan coated sweet treat can you eat before it becomes poison?

Other uses for mamey oil

I have also seen several references (1) on the pixtle seed oil being used as a treatment for jicaras when turning these gourds into drinking vessels. This seems similar to the use of chia seed oils which have been (and still are) used to laquer jicaras. I have found no specific source material for this information (yet) but Francisco Hernandez does note in his blurb on tezontzapotl “se aplica igualmente para reazar el color a las llamadas xícaras y a toda clase de ma era” (It is also used to enhance the color of so-called xícaras and all kinds of materials.)

- usually the reference will be a rewording of “The seeds contain a white semi-solid oil called sapuyucol or zapoyola, which was used in olden times to fix paintings and colours on gourds and other handicrafts.”

The jicara above is more elaborate than the standard, small bowl type of drinking gourd.

References

- Alia-Tejacal. I. Villanueva-Arce. R. Pelayo-Zaldívar. C. Colinas-León. M.T. López-Martínez. V. & Bautista-Baños. S. (2007). Postharvest physiology and technology of sapote mamey fruit (Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) HE Moore & Stearn).Postharvest Biol Tec, 45, 285-297. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2006.12.024.

- Almeyda, Narciso & Martin, Franklin W. (1976) Cultivation of Neglected Tropical Fruits with Promise Part 2. The Mamey Sapote (1976) AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE PB84-112515 ARS-S-156 November 1976

- Aragon-Martinez, Othoniel H & Martinez-Morales, JF & Alonso-Castro, Angel & Isiordia-Espinoza, Mario & González Rivera, María Leonor & Galicia-Cruz, Othir. (2017). Could the seed of mamey sapote relieve the postoperative pain?. Transylvanian Review: Vol XXV, No. 22, November 2017

- Badari Nath, A. R. S., Sivaramakrishna, A., Marimuthu, K. M., & Saraswathy, R. (2015). A comparative study of phytohaemagglutinin and extract of Phaseolus vulgaris seeds by characterization and cytogenetics. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 134, 143–147. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2014.05.08610.1016/j.saa.2014.05.086

- Bautista-Baños, Silvia & Díaz-Pérez, Juan & Villanueva, Ramón. (2005). Sapote mamey: Postharvest behavior and storage of a valuable tropical fruit.

- Bonita, Lourembam Chanu, Devi, G. A. Shantibala, & Singh, Ch. Brajakishor. (2020). Lima Bean (Phaseolus Lunatus L.) – A Health Perspective. International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research VOLUME 9, ISSUE 02, FEBRUARY 2020 ISSN 2277-8616

- Canales, G.A.A. (1946). Aceite de la Semilla de Calocarpum mammosum (Mamey). Características y Composición. BSc Thesis, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Químicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 52 pp

- Cárdenas-Hernández, Eliseo & Torres-León, Cristian & Chávez, Mónica L. & Ximenes, Rafael & Gonçalves-Silva, Teresinha & Ascacio-Valdés, Juan & Martínez-Hernández, José & Aguilar, Cristobal. (2024). From Agroindustrial Waste to Nutraceuticals: Potential of Mango Seed for Sustainable Product Development. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 154. 104754. 10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104754.

- César, Julio & Quero, Javier (2000) Bebidas y dulces tradicionales de Tabasco. Cocina indígena y popular ; 23; CONACULTA ISBN : 9701851242 – ISBN : 9789701851241

- European Food Safety Authority (2004). Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Food additives, Flavourings, processing Aids and Materials in Contact with Food (AFC) on a request from the commission related to hydrocyanic acid. The EFSA Journal 2004, 105, 1 – 28.

- Farrer, Brian T & Pecoraro, Vincent L (2003) Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology (Third Edition), Academic Press,

- 2003,ISBN 9780122274107, https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-12-227410-5/00055-7.

- García, M. C., González-García, E., Vásquez-Villanueva, R., & Marina, M. L. (2016). Apricot and other seed stones: amygdalin content and the potential to obtain antioxidant, angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitor and hypocholesterolemic peptides. Food & Function, 7(11), 4693–4701. doi:10.1039/c6fo01132b

- Jamieson, G. S., & McKinney, R. S. (1931). Sapote (mammy apple) seed and oil. Oil & Fat Industries, 8(7), 255–256. doi:10.1007/bf02574575

- Lim, T. K. (2012). Pouteria sapota. Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants, 138–142. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5628-1_24

- Milazzo S, Horneber M. (2015) Laetrile treatment for cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 28;2015(4):CD005476. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005476.pub4. PMID: 25918920; PMCID: PMC6513327.

- Morera JA. 1994. Sapote (Pouteria sapota). In Neglected Crops:1492 from a Different Perspective. JE Hernándo Bermejo and J León (Eds.) Plant Production and Protection Series 26. Rome, Italy. 103–109.

- Morton J. 1987. Sapote. In Fruits of Warm Climates. JF Morton, Miami, FL. EEUU.

- PDQ Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board. Laetrile/Amygdalin (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. 2022 Jun 14. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65988/

- Phillips, R.L., Malo, S.E. and Campbell, C.W. (1994). The mamey sapote. Fact Sheet HS-30. Univ. of Florida

- Rietjens, I. M. C. M., Martena, M. J., Boersma, M. G., Spiegelenberg, W., & Alink, G. M. (2005). Molecular mechanisms of toxicity of important food-borne phytotoxins. Molecular Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 131 – 158 DOI 10.1002/mnfr.200400078

- Solís-Fuentes, J. A., Ayala-Tirado, R. C., Fernández-Suárez, A. D., & Durán-de-Bazúa, M. C. (2015). Mamey sapote seed oil (Pouteria sapota). Potential, composition, fractionation and thermal behavior. Grasas y Aceites, 66(1), e056. doi:10.3989/gya.0691141

- Sosa-Baldivia, Anacleto, Guadalupe Ruiz-Ibarra, Raúl René Robles de la Torre, Reyna Robles López, and Aurora Montufar López. 2018. “The Chia (Salvia Hispanica): Past, Present and Future of an Ancient Mexican Crop.” Australian Journal of Crop Science 12 (10): 1626–32.

- Tacias-Pascacio, V.G.; Rosales-Quintero, A.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Castañeda-Valbuena, D.; Díaz-Suarez, P.F.; Torrestiana-Sánchez, B.; Jiménez-Gómez, E.F.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. (2021) Aqueous Extraction of Seed Oil from Mamey Sapote (Pouteria sapota) after Viscozyme L Treatment. Catalysts 2021, 11, 748. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal11060748

- Van, Thi & Do, Thi & Suhartini, Wildan & Phan, Chiuyen & Zhang, Zhengwei & Gökşen, Gülden & Lorenzo, Jose M.. (2023). Nutritional value, phytochemistry, health benefits, and potential food applications of Pouteria campechiana (Kunth) Baehni: A comprehensive review. Journal of Functional Foods. 103. 105481. 10.1016/j.jff.2023.105481

- Vázquez-de-Ágredos Pascual, Maria Luisa, María Teresa Doménech Carbó, and Antonio Doménech Carbó. 2008. “Resins and Drying Oils Os Precolumbian Painting: A Study from Historical Writings. Equivalences to Those of European Painting.” ARCHÉ Publicación Del Instituto de Restauración Del Patrimonio de La Universidad Politécnica de Valencia 3: 185–90.

Websites

- 4 Formas de decir Mamey en algunas lenguas : Pixtle, la semilla que da espuma y sabor a almendra – https://www.mexicodesconocido.com.mx/pixtle.html?fbclid=IwY2xjawKGMd1leHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETFyeHFvY2lBaG5pUUtacE1JAR5rRybWMWYXUvU4xOhHjJpRYsACLhO_f0wjlTiAgCfIOjgnFq3XSP3I3jaHPg_aem_UsSMBe7DoqVj8xEQzgbPzQ

- A delicious substitute of Cacao drink using Mamey Sapote seeds – https://flaar-mesoamerica.org/2024/07/19/a-delicious-substitute-of-cacao-drink-using-mamey-sapote-seeds/

- A Novel Tripartite Approach to Biomolecule Analysis for the Identification of Unknown Artistic Materials Applied to the Use of Chia Oil in Art from New Spain – https://arche.cnrs.fr/research_projects/chia-oil/

- A short account of the Sapota Mamey – https://pointsofdeparture.wordpress.com/2012/06/16/a-short-account-of-the-sapota-mamey/

- Azúcar Blanca y Mascabado – Asociación Mexicana de Diabetes en la Ciudad de México, A.C. – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=3110707952365448&set=a.169780109791595

- Cocina Indigena Chontal – https://gastronomiadetabasco.wordpress.com/inicio/cocina-indigena-chontal/?fbclid=IwY2xjawJ_v3pleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETFwT0RjWHN2ZmxHUGtMZ0VhAR6Ka1wtANmuw4WZ12vN86cm5ub3bBbAQG1kGbbaVdSWDNpw9RDcgEojp8T8Yg_aem_JLTjutiAnQB9Nt3_hl_KYQ

- Conoces estos tipos de azúcar – Imagen Radio – https://www.facebook.com/ImagenRadio/photos/a.356297377790524/3237643799655853/

- Enchiladas de pixtle (recipe) – https://cookpad.com/es/recetas/16883799-enchiladas-de-pixtle

- Enchiladas totonacas de zapote mamey El Pixtle o Pixtli.(image) – Latino Detroit – https://latinodetroit.com/enchiladas-totonacas-de-zapote-mamey-el-pixtle-o-pixtli/

- Ficha tecnica del mamey – https://www.monografias.com/trabajos89/ficha-tecnica-del-mamey/ficha-tecnica-del-mamey

- Fun Facts about the Mammee Apple : Point Fortin Public Library – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=485897253053239&set=a.118568369786131

- https://www.cocinadelirante.com/recetas/refrescante-agua-de-hueso-de-mamey-pixtle-no-lo-tires

- INAH TABASCO – (Image : woman grinding maiz for pozol) – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=650898449747301&set=pcb.650898526413960

- Macuspana Aquiles Serdan-San Fernando – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1096132742529468&set=a.436160001860082

- Mamei (woodcut image) – https://uctp.blogspot.com/2006/12/indigenous-medicinal-plants-of.html

- Mamey street vendor – via thecuriousmexican – https://www.instagram.com/p/Cq3HpfOO5rT/?img_index=2

- Mamey, pixtle y taxcalate (recipe) – https://foodandtravel.mx/recetas/dulces/mamey-pixtle-y-taxcalate/

- Mammea americana – Mamey Apple (image) – https://www.tradewindsfruit.com/mammea-americana-mamey-apple-seeds

- Mas madre solida (image) – https://lacocinadefrabisa.lavozdegalicia.es/masa-madre-solida-elaboracion/

- ¡No lo tires! Así puedes preparar una refrescante agua de hueso de mamey – https://www.gastrolabweb.com/bebidas/2021/6/1/no-lo-tires-asi-puedes-preparar-una-refrescante-agua-de-hueso-de-mamey-10860.html

- Pectin NH – https://www.pastryclass.com/articles/difference-between-pectin-and-pectin-nh-explained

- Pixtamal – https://laroussecocina.mx/palabra/pixtamal/

- Pixtle – https://gourmetdemexico.com.mx/gourmet/cultura/que-es-el-pixtle-y-como-se-consume/?fbclid=IwY2xjawJ7rYZleHRuA2FlbQIxMABicmlkETFxSEFHNnB4dW1PbUtTbGVEAR4AefsfK5XxC218LWOEULOC99Fw3zc2GETkZ466gtZESDuwaeNJ6y1_Pz-vMw_aem_2M9BzURsa_LSms-bt-kOow

- Pixtle (image : whole seed) – https://www.mexicodesconocido.com.mx/pixtle.html

- Pixtle (image : cracked seed) – https://naturalpoland.com/en/products/food-and-cosmetic-oils/oil-of-mamey-sapote/

- Pixtle conchas (image) via Tierra Adentro, cocina on Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2161506353936407&id=1869556436464735&set=a.1875985002488545

- Pouteria – http://floranorthamerica.org/Pouteria

- Pouteria – https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/83117-Pouteria

- Pozol Con Pixte – https://issuu.com/editorialolmeca/docs/bebidas_y_dulces_tradicionales_de_tabasco/s/25986196

- Roof top restaurant – Sofitel Mexico City Reforma – https://www.therooftopguide.com/rooftop-bars-in-mexico-city/cityzen.html

- Seed warning – https://specialtyproduce.com/produce/Mamey_Sapote_109.php

- Tezontzapotl – https://www.personal.unam.mx/Docs/Cendi/Frutas-muy-mexicanas.pdf

- Totonac mamey sapote enchiladas (recipe) – https://deliciasprehispanicas.com/2018/07/27/enchiladas-totonacas-de-zapote-mamey/

- Tzapotl – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tzapotl

DRY the mamey seed in the sun until you hear the movement of the almond inside when you shake it.