We can thank Mexico (and mesoamerica in general) for chocolate. How chocolate is done outside of Mexico is very different to how it was traditionally used. One aspect of this is the variety of drinks produced from chocolate (1) and another is the equipment used. I have looked at one of these tools previously (2) and today I would like to look at another, the alcahuete.

- For more information on this see………A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Appendix 2 : Chocolate Drinks

- Mexican Cooking Equipment : The Molinillo

There has long been a variety of mixing sticks used for various drinks. The most well known (probably) are the swizzle sticks used in cocktails.

Well now I would like to introduce you to the Mexican swizzle stick for chocolate/atole called the alcahuete.

First some etymology.

acuahuitl.

Principal English Translation: a stirring stick; also, a personal name (see attestations)

Orthographic Variants: acuauitl, aquahuitl, acuavitl, acuauitl

Attestations from sources in English: aquaujtl [aquahuitl] = spoons for stirring cacao (central Mexico, sixteenth century)

Fr. Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain; Book 1 — The Gods; No. 14, Part 2, eds. and transl. Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble (Santa Fe and Salt Lake City: School of American Research and the University of Utah, 1950), 19.

“una paleta de tortuga, con que se rebuelve el cacao” = a tortoise shell stick for stirring cacao; a comment provided in a footnote to Dibble and Anderson’s Florentine Codex, Book 9, page 28, note 8.

The word evolved in Oaxaca, a State well known for a superlative chocolate drink called tejate. Oaxacan Spanish borrowed the word alquauitl, “the stick for [stirring] drinks,” from Nahuatl (1). Bernardino de Sahagún recorded in his 16th century encyclopaedia of Nahuatl culture (in the Spanish version) (2): “Then came those who sold the cacao and gave each one a gourd of cacao, and [to] each one they gave their stick, which they call a[l]quauitl”). .

- Before the arrival of the Spanish under Cortés in the 16th century, Oaxaca was a region of diverse indigenous languages. The primary languages spoken were Zapotec, Mixtec, Mazatec, Chinantec, and Mixe. Additionally, other languages like Nahuatl, Huave, and Chontal were also present, though less widespread.

- The Spanish translation of the Nahuatl differs somewhat in content.

Sahaguns translation (particularly the quauitl part) is interesting as it (in one translation) boils down to being a “stick” of wood. One that (I assume) is, or can be, used to mix your drink.

Quauitl : Noun : Classical Nahuatl

Alternative spelling of cuahuitl

cuahuitl.

Principal English Translation: stick; wood; tree(s); a forest

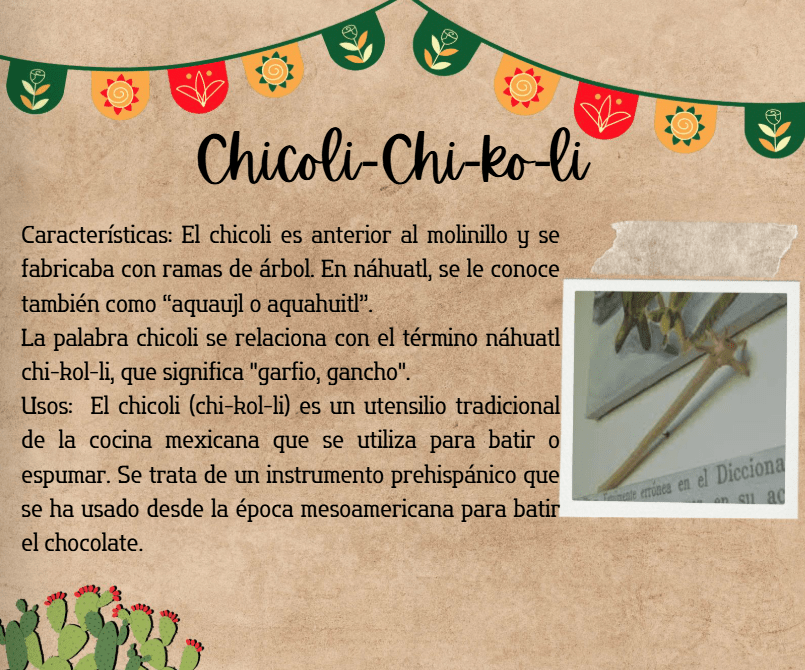

The chicoli as shown above is the perfect example of a mixing “stick” and also shows the beginning of the evolution of the molinillo as we know it today.

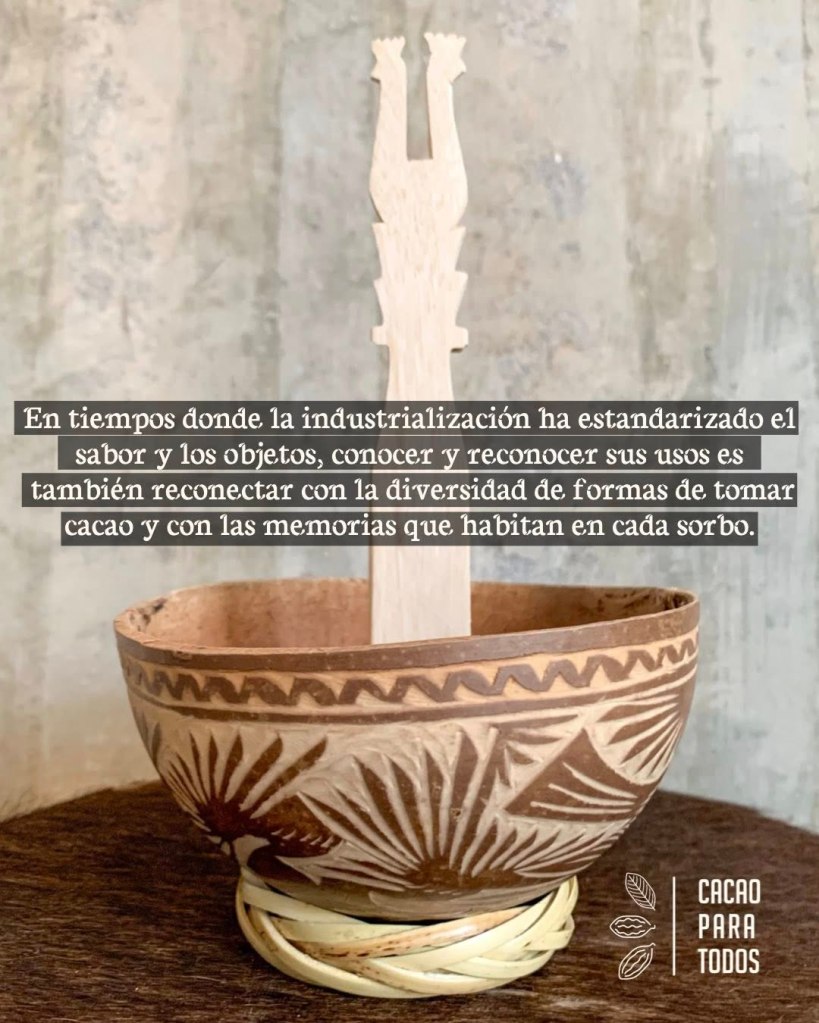

The alcahuete is different to these though. It is not used to create a foam (espuma) on the drink as the molinillo does but rather it is part swizzle stick and teaspoon.

Of the word alcahuete (as it refers to the stirring stick) van Doesburg (2023) notes that “ as a loanword with this “second meaning” it exists only in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca”. This “second meaning” (or rather the first) according to the to the Royal Spanish Academy, it is a “person who arranges, conceals, or facilitates a love affair, usually illicit.” (1) It comes from the Andalusian Arabic alqawwád , meaning “the messenger [esp. de amor],” and passed into Spanish before the 13th century.

- Although this can be translated as “pimp” it can also be a lot more innocent than that and can refer to the friend that backs you up when their parents don’t approve of their child’s romantic choice and you help them to meet in secret. Ah, young love.. The word pimp is of unknown origin. It first appeared in English around 1600 and was used then as now to mean “a person who arranges opportunities for sexual intercourse with a prostitute.” Some think it comes from the 16th century French word “pimper,” which means “alluring or seducing in outward appearance.”

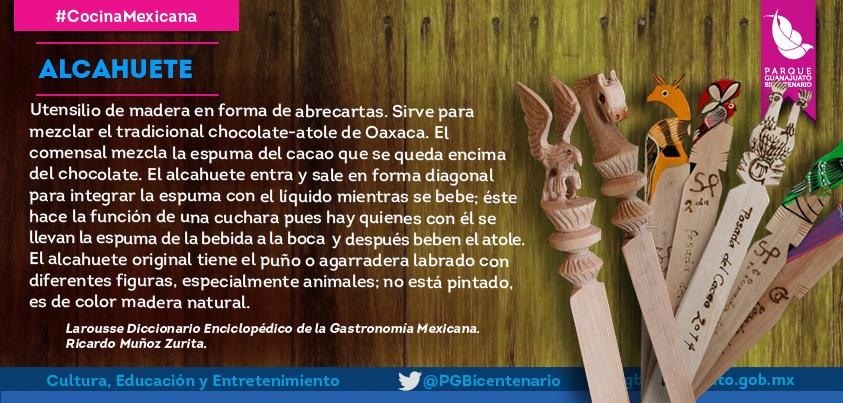

The alcahuete is a wooden utensil often described as “shaped like a letter opener” and is used (by the imbiber, not the cocinero) to stir the traditional Oaxacan chocolate-atole. The “letter opener” description is an interesting one and shows both the evolution and devolution of the alcahuete (more on this in a little).

La Merced Mercado, Oaxaca City

The diner stirs the cocoa foam in and out diagonally to blend the foam into the liquid while drinking. It is also used to stir up the sediment (from the traditional cacao and corn-based beverages) that tends to settle at the bottom of the drinking vessel. If you’ve made horchata you know what I mean. The alcahuete also acts as a spoon so you can use it to bring the foam to your mouth and then drink the atole.

The original alcahuete has a handle carved with various figures, especially animals; it’s unpainted, a natural wood colour, and, above all, it doesn’t have a point or a knife shape.

Known in Zapotec as yag gai (rooster stick – palo del gallo), they are made by artisans in communities like Santa Cecilia Jalieza and are characterized by their decorative carvings depicting animals or other symbolic motifs.

In Oaxaca City, tourists buy them as letter openers; artisans realized this and now make many more letter openers than alcahuetes. In fact, unpainted and pointless alcahuetes are now hard to find, so curiously, they are sold more as handicrafts than as kitchen utensils. La Fundación Alfredo Harp Helú Oaxaca notes that in the Central valleys of Oaxaca the (traditionally) plain wooden implements have become slimmer and now come with a colourfully painted animal on top and have become more like “bookmarks” for tourists than a functional kitchen/dining implement.

Note the differences in the alcahuetes in the image below. The central (top and bottom) images show alcahuetes with the “spoon” function.

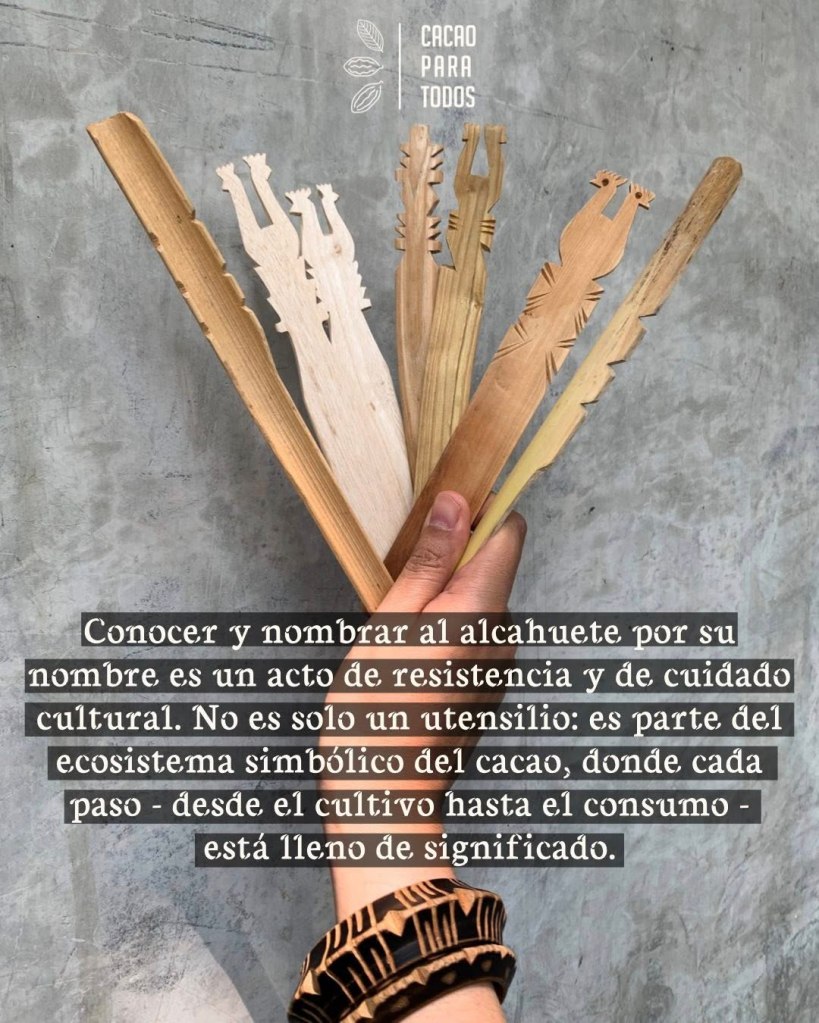

It has been said that the alcahuete is a utensil that is in danger of being forgotten. I think it is more than just this. It is a fragment of culture that is being lost.

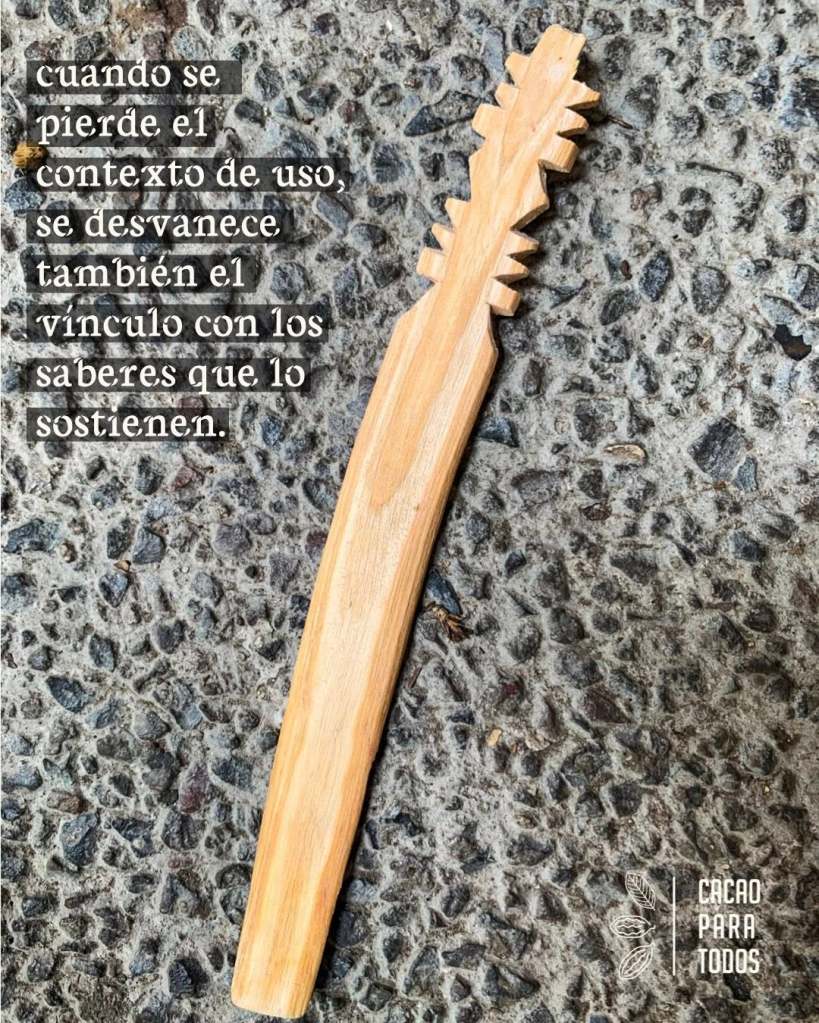

In markets and workshops, many artisans today call it a “separator” (“separador”) to sell it, because those unfamiliar with it don’t understand its use or its original name. This change of name is a sign of cultural detachment: when the context of use is lost, the connection to the knowledge that sustains it also fades. Preserving the use and knowledge of cacao is not a matter of nostalgia, but of cultural resistance.

In a world where cacao has been globalized, standardized, and commodified, recovering local ways of consuming it – with their rhythms, tools, and knowledge – is an important act of memory and identity.

Knowing and naming the alcahuete is an act of resistance and cultural care. It’s not just a utensil: it’s part of the symbolic cocoa ecosystem, where every step – from cultivation to consumption – is imbued with meaning.

When the context of use is lost, the link with the knowledge that sustains it also vanishes.

This utensil seemed to be a recent type of utensil restricted to the Oaxaca region, but our research (1) has allowed us to locate precedents at least from the 16th century, when the Mexica elites (and perhaps also the Mixtecs) used prized aquahuitl made of wood or tortoise shell to mix their cacao drinks.

- Fundación Alfredo Harp Helú Oaxaca (more on this in a bit)

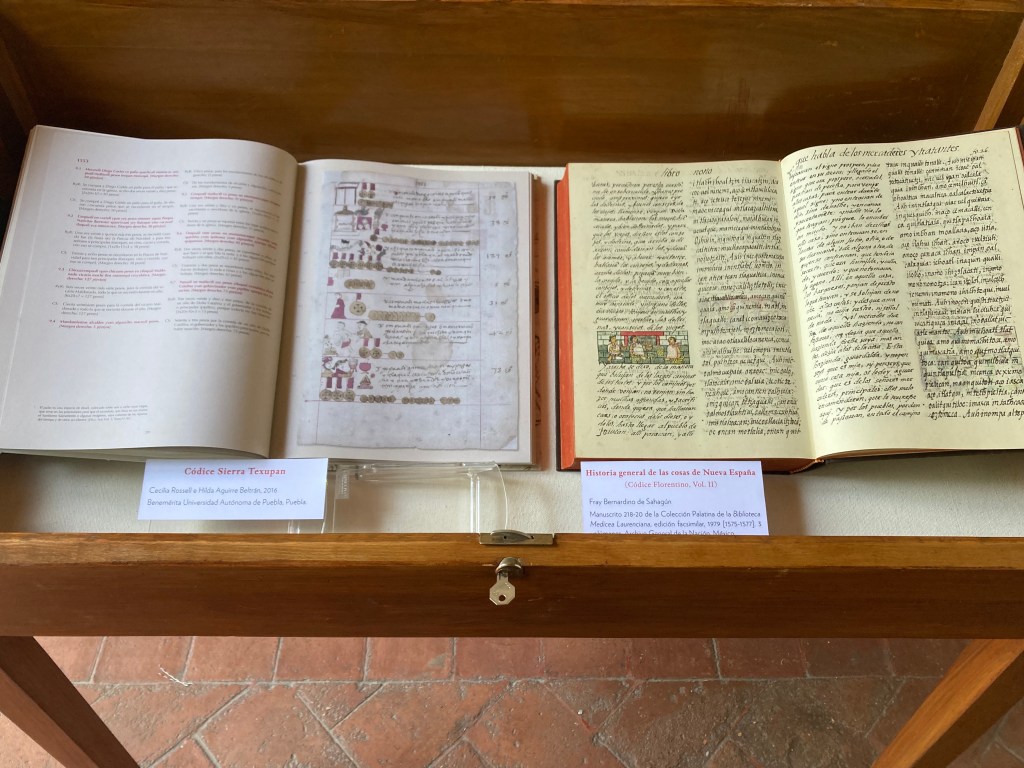

The researchers gleaned their information from “documents of the time” including testamentos (1), procesos inquisitoriales (inquisitorial processes) (2) and, most notably, the códices Florentino y Texúpan.

- “Testamentos” (singular: “testamento”) in Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian refers to a will or testament. It’s a legal document that outlines how someone wishes their property to be distributed after their death.

- An inquisitorial system is a legal system in which the court, or a part of the court, is actively involved in investigating the facts of the case. This is distinct from an adversarial system, in which the role of the court is primarily that of an impartial referee between the prosecution and the defence. In an inquisitorial system, the trial judges (mostly plural in serious crimes) are inquisitors who actively participate in fact-finding public inquiry by questioning defence lawyers, prosecutors, and witnesses. They could even order certain pieces of evidence to be examined if they find presentation by the defence or prosecution to be inadequate. Prior to the case getting to trial, magistrate judges participate in the investigation of a case, often assessing material by police and consulting with the prosecutor. In an adversarial system, judges focus on the issues of law and procedure and act as a referee in the contest between the defence and the prosecution. Juries decide matters of fact, and sometimes matters of the law. Neither judge nor jury can initiate an inquiry, and judges rarely ask witnesses questions directly during trial. Pfft. Legal mumbo jumbo. We all know what a “Spanish Inquisition” entailed

(Merriam-Webster dictionary)

These are the images of the texts as displayed

The Florentine Codex is an old friend by now but the codex Texúpan is a new one to me.

The Sierra Texupan Codex is a colonial pictographic Mesoamerican manuscript. It is an account book of Mixtec people of Tuxupan, in the Oaxacan region of New Spain, from Santa Catalina Texupa (in the modern Mexican state of Oaxaca), declaring their income and expenses between 1551 and 1564. The manuscript is composed of 62 sheets of paper. It is bound in codex, that is, with pages attached to a spine, similar to a modern printed book. It uses both alphabetic and pictorial modes of writing. On the left side of each page are pictographs while on the right side is text in the language of government in the former Aztec Empire, Nahuatl, using the Latin alphabet used by the Spanish (and by most Europeans). This codex is one of the best sources of information on the local production of silk in New Spain.

A close up of the image of the page of the codex Texúpan as shown in the display.

Alcahuetes?

I am having trouble finding the corresponding word in the attached text though

No. I am not a Millennial. Yes. I can read cursive.

BOOM

Didn’t expect that did ya.

A lot of the information in this Post was sourced from the Alfredo Harp Helú Oaxaca Foundation (FAHHO). FAHHO (1) is a non-profit organization that promotes community projects. Its areas of focus include education, culture, sports, health, productive activities, and environmental protection. The purpose of the Alfredo Harp Helú Oaxaca Foundation is to generate initiatives aimed at improving the quality of life of the people of Oaxaca.

- La Fundación Alfredo Harp Helú Oaxaca

Fundación Alfredo Harp Helú Oaxaca

Mission

Our mission is to conserve and disseminate the natural and cultural heritage of Mexico, and Oaxaca in particular, as well as to preserve memory, disseminate knowledge, and promote inclusion and equity. This is done to reduce educational gaps, combat the abandonment of heritage, reduce environmental damage, promote health and sports, foster productive projects, and foster appreciation, respect, and love for all human beings.

Vision

We are driven by the vision of a more prosperous and just Mexico, which will be achieved by working today on sustainable projects that benefit future generations.

We want to contribute to Mexico’s sustainable development, to building a more just and equitable society, and to raise awareness about the care of our natural and cultural heritage. Every day, we express the beauty that surrounds us, promote and restore our inherited heritage, enrich natural landscapes, and safeguard beautiful collections of philately, books, documents, and textiles. Our spaces and activities are free and promote a more humane world.

Alfredo Harp Helú (born 1944) is a Mexican businessman of Lebanese origin, and as of 2011, with a net worth of $1.5 billion, is according to Forbes the 974th richest person in the world. He is also the cousin of the Mexican multibillionaire Carlos Slim Helú. He was kidnapped in 1994 and held for 106 days, but he was eventually released after his family paid a $30 million ransom.

References

- Dakin, Karen & Wichmann, Søren. (2000). CACAO AND CHOCOLATE. Ancient Mesoamerica. 11. 55 – 75. 10.1017/S0956536100111058.

- Terraciano, Kevin (2021) Codex Sierra: A Nahuatl-Mixtex Book of Accounts from Colonial Mexico (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

- van Doesburg, Sebastian (2023) Sobre la palabra alcahuete en el español de Oaxaca – https://fahho.mx/cat/publicaciones/boletin-fahho/digital-no-31-oct-2023/

Websites

- Acuahuitl – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/acuahuitl

- Alcahuetes – Larousse Cocina: https://laroussecocina.mx/palabra/alcahuete/

- Alcahuetes via Cacao Para Todos on Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/CacaoParaTodos/posts/pfbid02AEG2zdLsWTd6eCrqLQoKT5FnAujk9djBic9bAqTs7Z8ZHGLW1npyj464TpqDXYQvl

- Actividades de la Posada del Cacao 2014, Oaxaca – https://www.viveoaxaca.org/2014/12/posada-del-cacao-2014-oaxaca.html

- Alquahuitl – https://fahho.mx/author/comunicacion2/page/22/

- El Xochitlicacan y el Quauitl-xicalli del recinto sagrado de México Tenochtitlan: el árbol como símbolo de poder en el México antiguo. (2013). Dimensión Antropológica, 59, 7-50. https://revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/dimension/article/view/767

- Fundación Alfredo Harp Helú Oaxaca – https://fahho.mx/sobre-nosotros/

- Preparan alcahuetes para saborear la Posada del Cacao, del 13 al 14 de diciembre – https://presslibre.mx/2014/12/07/preparan-alcahuetes-para-saborear-la-posada-del-cacao-del-13-al-14-de-diciembre/

- Sobre la palabra alcahuete en el español de Oaxaca – Sebastián van Doesburg – Boletín FAHHO Digital No. 31 (Oct 2023) – https://fahho.mx/sobre-la-palabra-alcahuete-en-el-espanol-de-oaxaca/

- Spanish Inquisition (image) – https://www.britannica.com/summary/Spanish-Inquisition-Key-Facts