So.

What is Mike complaining about?

The radish (rábano en español)

The radish (Raphanus sativus) is a flowering plant in the mustard family, Brassicaceae, which also includes Brassica rapa – the turnip, Brassica oleracea – the cabbage and its relatives (1); and Armoracia rusticana – horseradish. Other herbs in this family include arugula (rocket), mustard, and watercress (horseradish should be here I guess. I consider it more a herb than a vegetable like the turnip or cabbage).

- kale, collard greens, broccoli, cauliflower, kai-lan, Brussels sprouts, kohlrabi

The radish is prized for its large taproot which is commonly used as a vegetable, although the entire plant is edible and its leaves are sometimes also eaten as a vegetable.

Raphanus was the Roman name for the radish

- The generic name Raphanus derives from the Greek ραφανις (raphanis) (quickly appearing), from ra, meaning quickly, and phainomai, meaning to appear, in reference to the rapid germination of radish seeds

- Sativus is Latin for ‘cultivated’.

- The common name radish derives from the Latin for root, radix

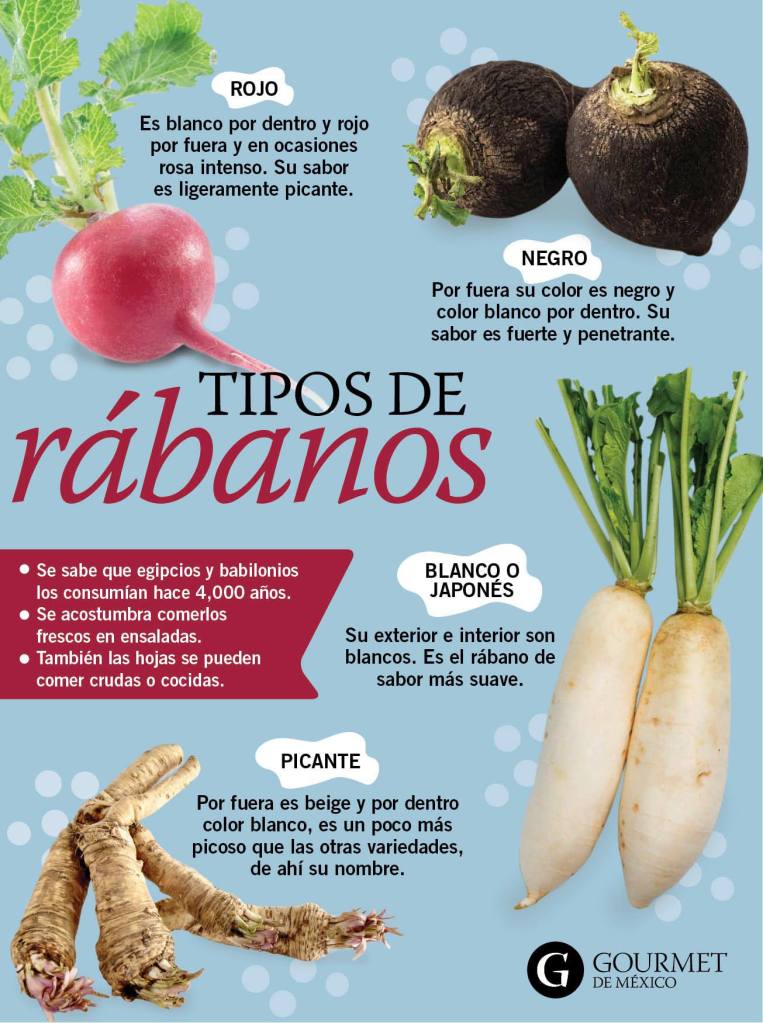

The radish root abounds in a multitude of varieties

Radishes are not native to Mexico.

Scientists tentatively locate the origin of Raphanus sativus in Southeast Asia, as this is the only region where truly wild forms have been discovered. (Fuks et al 2020)

The radish was one of the first vegetables introduced into the New World. By 1500 radishes were under cultivation in Mexico, in 1565 they’d made it to Haiti (1) and were being grown by English colonists in Massachusetts by 1629.

- I’m still trying to find the source for this. EVERYONE quotes it almost verbatim.

Radishes are noted on a seed order list from 1631 which was made by John Winthrop Jr., the son of the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Johns list is interesting as it contains very few vegetables and most of those are root vegetables (beets, carrett, parsnip, radish) there are couple of others in the brassica family (cabedg and cauliflower), and some alliums (leekes and onyons) but most are herbs and flowers. There are a lot of medicinals but the most interesting to me are the wild and weedy ones, the now introduced quelites. Cresses, corn sallett, mallow, pursland, rockett, sorrell and even the spynadg, all the leafy greens, plants not really a part of agriculture (like wheat or corn might be) but wild plants bought in from the margins and cultivated.

The radish quickly caught on in the Americas and by 1848, there were 8 different varieties listed.

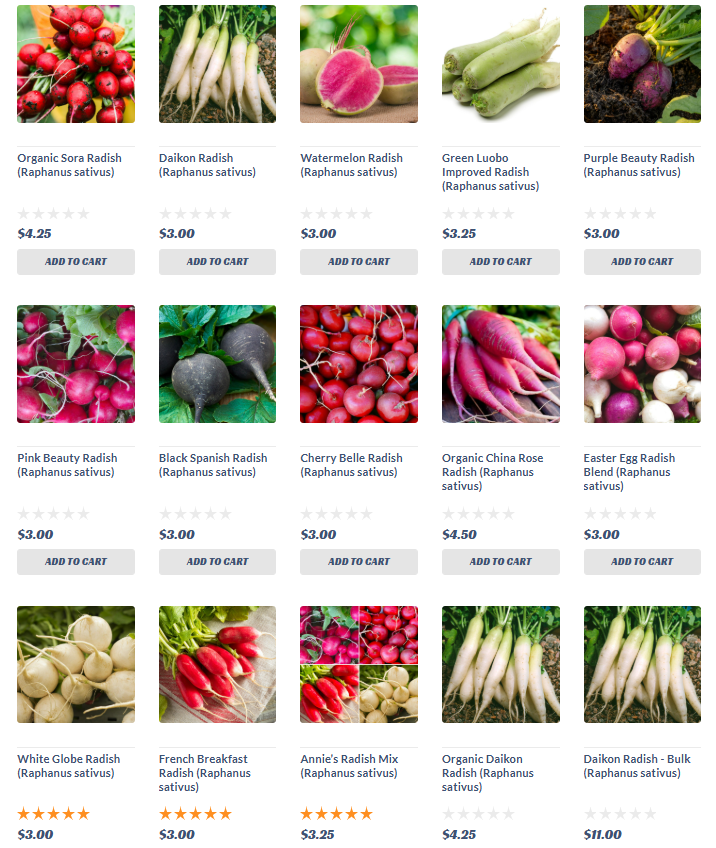

And if you check out Annie’s Heirloom Seeds today you’ll find over 40 options (with some double ups if you include the “organic” options)

In Oaxaca the radish was introduced by Spanish settlers and monks more than 200 years ago. It is largely believed that two Dominican monks encouraged local Zapotec and Mixtec farmers to grow the radishes, along with other fruits and vegetables they brought, for food. They encouraged this exchange of crops with all indigenous groups they encountered.

The radish really took off in Oaxaca.

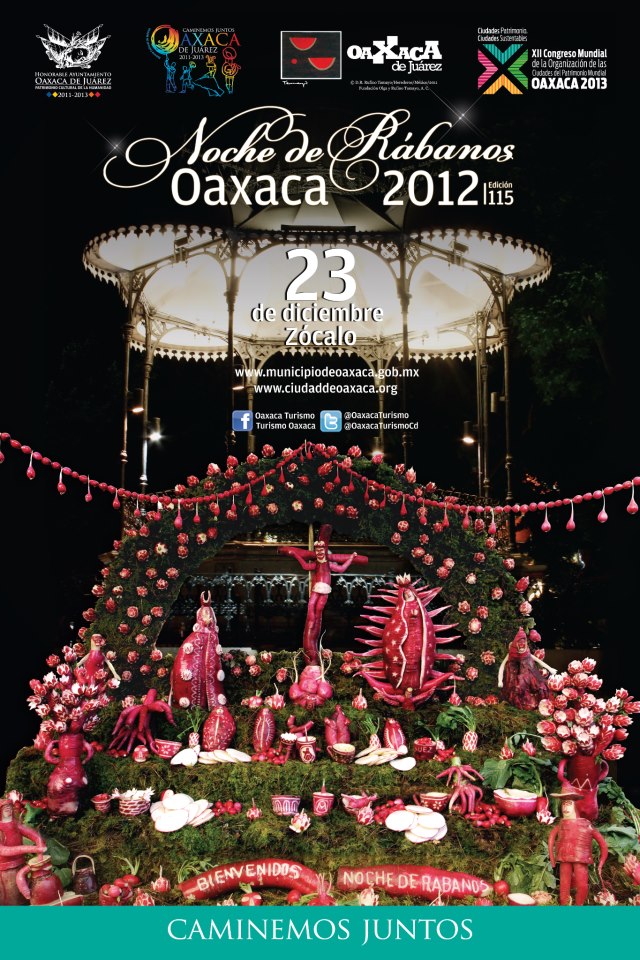

The Night of the Radishes or Noche de Rábanos is an annual Oaxacan competition held on the day of the Mercado Navideño (Christmas Market) on December 23rd in Oaxaca City , Mexico.

The event originated during the colonial era as a sales method used by farmers to attract buyers.

(Mashed)

(Scholastic Kids Press)

One year around the mid-eighteenth century, the crop of radishes was so abundant that part of the crop was not harvested and lay dormant for months. Then in December, two of the friars pulled up some of these forgotten radishes and were amazed and amused at the irregularly shaped and sized radishes. The friars took the misshapen roots to the Mercado Navideño where they soon began to attract crowds. Not long after someone came up with the idea of carving the roots. An idea which quickly spread. From this beginning evolved the idea of fashioning the radishes into nativity figures which would have been greatly encouraged by the clergy, and eventually a competition began.

In 1897 the City sponsored the first contest with a prize for the best nativity scene.

Yeah, that ones not a Nativity. More towards the other end of the process.

Eating the dirt apple

The how of it is fairly simple

Sometimes the radish is sliced and served on a small plate with cucumber slices; sometimes the radish is left whole and a small bunch with limes and salt is served (squeeze, sprinkle, and eat like a crunchy little crab apple)

But, as Mike is himself wondering…….

Why is the radish utilized in Mexican cuisine?

Theories abound.

- They create a foil to rich, fatty meats and sauces,

- They add a fresh and slightly bitter flavour contrast to rich sauces,

- They add their own pungent and peppery/spicy heat to the dish or (somewhat paradoxically),

- They offer cooling relief when eaten after picante foods,

- They operate as a palate cleanser between dishes.

Or they can be simply aesthetic by…..

- Adding a fresh crunchy texture to the dish or by,

- Adding visual appeal with their intense red skins and crisply snowy white insides.

From the point of view of a cocinero they are also quite handy as they can be chopped hours in advance and they will not wilt or go limp and they wont oxidise and brown (like an sliced apple will)(No, I don’t know what apples have to do with tacos. It’s just an example. Calm down would ya)

The history of the consumption of the radish goes back quite a ways…..

It is believed that radishes were cultivated in Egypt as early as 2700 – 220 B.C. (Banga 1976). In ancient Egypt radish seeds were pressed for oil. The people who built the pyramids were said to have been paid in onions, garlic and radishes. In 1996 tests were conducted on desiccated radish seeds from a 6th century AD storage vessel recovered from Qasr Ibrîm, Egypt (O’Donoghue et al 1996)

By the 1st Century AD the first recorded consumption (and domestication) of radishes by the Romans is recorded (they were likely eaten long before this though).

In historical records, (particularly the Roman historian Pliny) different classical authors refer to the use of radish oil, either as a fuel for oil lamps or as a staple food, and according to these texts, it was one of the most common oil crop commodities in Roman Egypt, due to its preferable properties such as, the quantity of produced product compared to sesame, castor and other oils, its nutritional value, and most importantly, lower taxes (Mayerson 2001). This paper also notes that testing of residues on various artifacts shows that radish oil (or perhaps rapeseed oil – a close relative of radish) was used in animal mummification in Roman Egypt.

A piece of archaeological art from Ostia—the port of Rome—includes a wall painting of a meal that was served to customers (above). It includes two kebab sticks with meat chunks, a layer of what seems to be pulses (lentils or chickpeas), a carrot or radish, and a small dish that may have held a sauce. The image also includes wine and bread. It represents a simple day-to-day meal for a middle-rank labourer

As an aside…..

During the time of Ancient Rome adultery was a serious offense and the penalties for it were brutal. The Athenians in particular did not fuck around when it came to the punishment of adulterers.

If an Athenian caught a man having intercourse with a free woman attached to his household, he could inflict a variety of punishments on him. The perpetrator apprehended in flagrante delicto (1) could be prosecuted or fined. If he was unable to pay restitution, the husband could depilate his testicles and anus with hot ash and shove a radish up his rectum (rhaphanidosis)(2). The goal of this ordeal was not simply revenge, but also humiliation. The purpose of this punishment, was to transform the anus into a vagina symbolically through depilation and then to violate it with a phallic radish. This allowed the aggrieved party to reassert his masculinity over an adulterer who had encroached on the women in his domain (O’Bryhim 2017).

- caught in the very act of wrongdoing, especially in an act of sexual misconduct.

- This radish was not the small, bulbous variety popular today, but resembled an enlarged carrot. (See the picture of the Roman meal above)

Ouch.

(You are so busted)

A 10th-century cookbook by the author and proto-food critic (?) al-Warrāq (1) includes the radish in a recipe as a side dish for ostrich meat and an ingredient in a chicken dish called kardanāj (kardabāj).

- Abū Muḥammad al-Muẓaffar ibn Naṣr ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq was an Arab author from Baghdad. He was the compiler of a tenth-century cookbook, the Kitāb al-Ṭabīkh (The Book of Dishes). This is the earliest known Arabic cookbook. It contains over 600 recipes, divided into 132 chapters.

(this isn’t the recipe though)

Kardanāj (here written as kardabāj); the Persian form gardanāj, which Savage-Smith (et al 2024) notes as being “hot roasted meat”. Nasrallah (2020) offers more insight “In (the) recipe (for) the dish called dajāj karnadāj, which is chicken (dajāj) grilled by rotating it on an open camp-like fire. In other sources, the word for grilling by rotating also occurs as kardhanāj and kardanāj”.

This though is much more than simply grilling.

It is a whole process.

In the section on “General Tips”…“The best way to grill chicken, whichever way you choose to do it, is to fatigue it [before slaughtering it] by running after it until it can no longer run from exhaustion. Choose a fat chicken, and slaughter it after feeding it vinegar and rosewater. After that, scald it as usual, and prepare a mix of sesame oil, salt, and a bit of saffron for it. Grill the chicken on slow low heat, and baste [the grilling rotating chicken] with it [i.e., the oil mix]. It will come out marvelously tender and delicious.”

*Misquotation of a misquotation of Hannah Glasse in “The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy” (1747) : “First catch your hare”

Now, this has nothing to do with nothing (my mind wanders sometimes). It was just an interesting thing that came up when researching the history of the radish.

Another (13th Century) chicken dish (with Persian influences) from Al-Andalus (1) taken from Kitab al tabikh fi-l-Maghrib wa-l-Andalus fi `asr al-Muwahhidin, li-mu’allif majhul (2) is worth a look at. This dish (and others like it) are theorised to be the forerunners of the quintessentially Mexican dish called mole. (3)

- also known as Muslim Iberia, or Islamic Iberia

- A different Kitab to the one mentioned earlier. This one, The Book of Cooking in Maghreb and Andalus in the era of Almohads came around 3 centuries later.

- What is Mole?

Like Mike, not everyone was taken with the radish.

Auguste Escoffier (1) declared in his 1934 edition of “Ma Cuisine”, the edible root was so common he felt no need to include it in his tome.

- Georges Auguste Escoffier; 28 October 1846 – 12 February 1935) was a French chef, restaurateur, and culinary writer who popularised and updated traditional French cooking methods. Known as “the king of chefs and the chef of kings,” he earned a worldwide reputation as director of the kitchens at the Savoy Hotel (1890–99) and is considered one of the most influential Western chefs in history.

Lets have a look at a dish where Mikes dirt apple is used ubiquitously in Mexico. Pozole.

Now I’m not going to go into the dish too much as there is a thesis worth of information to be had and many scientific papers have been written on the subject. Here’s a brief snippet.

Nor will I go into the background of cannibalism that shadows the history of the dish. I am not familiar enough with this dish nor it’s history. I have never cooked it myself (neither the human or non-human containing varieties).

Just the basics in this case.

Pozole is a “guisado” (or stew) made from maize kernels.

Most often you will see these kernels described as “hominy” but that is American word (from el otro lado – not the Mexican part) so we will use the Nahuatl word cacahuazintle (1).

- Also cacahuacintle, cacahuacentli. Borrowed from Classical Nahuatl cacahuacentli (“cacao pod”), from cacahuatl (“cacao bean”) + centli, cintli (“dried maize still on the cob”).

This is an old heirloom (1) variety of white dent corn (2) with large kernels and a distinctive flavour (3).

- An heirloom seed is an old variety (by definition pre-dating 1960’s) that is open pollinated, by either wind, insect or animal (humans included). Seeds collected will then produce a (nearly) exact copy of their parent plant, so by saving seeds from last season’s best tomato plant, we can enjoy them again in the next growing season (ad infinitum)

- Dent corn, also known as grain corn, one of 5 main varieties of maize, is a type of field corn with a high soft starch content. It received its name because of the small indentation, or “dent”, at the crown of each kernel on a ripe ear of corn. The other 4 varieties are flint, flour, sweet and popping

- Corn has flavours? This might be difficult to comprehend for anyone outside of traditional corn growing cultures as most of us are only exposed to fresh, yellow sweet corn (or popcorn), particularly in cultures based around wheat.

(note the “dent” in the kernels)

Now some etymology. You know how much I love that.

Pozole comes from the Nahuatl word posolli. Posolli is defined as a stew made of maize kernels. Pradeau (1974) notes that the word derives from the Nahuatl “pozol” which means frothy or foamy and refers to the phenomena that the dried kernels of cacahuazintle cause the cooking water to “foam up”.

posol : noun : po·sol pōˈsōl

variants or less commonly posole or pozole

1: a thick chiefly Spanish-American soup made of pork, corn, garlic, and chili

2: a Spanish-American drink made of cornmeal, water, and sugar

Etymology

American Spanish posol, pozol, posole, pozole, from Nahuatl pozolli (I’ve also seen it as potzolli), literally, foamy, from pozol foam

pozolli.

Principal English Translation:

this term literally means foam; but it entered Spanish as pozole and refers to a stew of maize kernels crushed and boiled along with ground chile peppers; it is made in the United States today with hominy and pork (see Karttunen)

posolli

Frances Karttunen:

POZOL-LI pork and hominy stew / pozole (X)[(2)Xp.65). See POZŌN.

Frances Karttunen, An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992), 205.

posole : noun : po·so·le pō-ˈsō-(ˌ)lā

variants : or pozole

: a thick soup chiefly of Mexico and the U.S. Southwest made with pork, hominy, garlic, and chili

Etymology

Mexican Spanish, from Nahuatl pozolli, from the base of pozōn – boil, be covered with foam

Pozōn was a weird one. many non-foamy definitions came up for this one. Relevant? Probably not. I do find it interesting though.

Anatomy:

In human anatomy, “pozón” means “nipple”. In animal anatomy, it refers to the “teat”.

Botany:

In botany, “pozón” refers to the “stalk” of a plant, especially the part that supports the fruit or flower.

also

pozón

Meanings of “pozón” in English Spanish Dictionary

Category Spanish English

1 whirlpool

2 eddy

pozón

From Old Spanish, inherited from Latin potiō (“potion, drink”), unlike the borrowed form poción. Doublet of ponzoña.

OK, enough nerding out for me. Back the the food.

Pozolería Mi Tierra Culhuacán

Gracias por tu pozole Arnie

Arnie “ArnieTex” Segovia is a Texas based BBQ pitmaster who cooks authentic, and simple, Mexican-American comfort food. His creations are a traditional blend of Southwest, Texas, and Norteño cooking techniques, both in the kitchen and over open fire.

Now there’s not going to be a recipe in this Post (maybe I should have warned you about this at the start). The recipe will eventually get it’s own Post. After I have learned to cook it (and it has been accepted by my Mexican friends)

The radish family also contains medicinal utility.

Medicinal uses of the radish.

In the 9th Century Asaph the Jew (1) noted that the radish, particularly its leaves, may be useful in traditional medicine to increase mucus and his Nabatean contemporary, Ibn Wahshiyya (2) considered it a component of poison antidotes. A little over 2000 years later Maimonides (3) also highlighted its medicinal uses.

- Asaph the Jew (9th Century BC), also known as Asaph ben Berechiah and Asaph the Physician is a figure mentioned in the ancient Jewish medical text the Sefer Refuot (Book of Medicines). Thought by some to have been a Byzantine Jew and the earliest known Hebrew medical writer (Rosner 1995)

- Ibn Waḥshiyya (His full name was Abū Bakr Aḥmad ibn ʿAlī ibn [Qays ibn] al-Mukhtār ibn ʿAbd al-Karīm ibn Ḥarathyā ibn Badanyā ibn Barṭānyā ibn ʿĀlāṭyā al-Kasdānī al-Ṣūfī)………pause for breath…… (died c. 930), was a Nabataean (Aramaic-speaking, rural Iraqi) agriculturalist, toxicologist, and alchemist born in Qussīn, near Kufa in Iraq. He is the author of the Nabataean Agriculture (Kitāb al-Filāḥa al-Nabaṭiyya), an influential Arabic work on agriculture, astrology, and magic. (Hämeen-Anttila 2006)

- Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204 AD), commonly known as Maimonides and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam was a Sephardic rabbi and philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah scholars of the Middle Ages. Aside from being revered by Jewish historians, Maimonides also figures very prominently in the history of Islamic and Arab sciences. Influenced by Aristotle, Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, and his contemporary Ibn Rushd, he became a prominent philosopher and polymath in both the Jewish and Islamic worlds.

Lets step forward in time several hundred years.

According to the websites advertising the above products……(here for educational purposes only…….)

- Rabano Yodado – Keep yourself healthy and strong by taking this Rabano Yodado. It contains potassium iodide, which helps to clean out your lymphatic system. The lymphatic system plays a major role in transporting fatty acids and fats from your digestive system, as well as antigen-presenting cells to your lymph nodes. This dietary vitamin helps to stimulate the production of energy. It is also an antibacterial and antiviral and it helps to treat the bronchial states and detoxifies your body and skin.

- Ranabo Negro (Clormax) – Main Benefits: Helps with kidney and bladder problems and urinary tract infections. Useful in reducing cholesterol, improves liver function, disintegrates gallstones and kidney stones. The consumption of this product is the responsibility of the consumer and the person who recommends it. Main Ingredients: Black Radish, Juniper, and Toad Grass (Hierba Del Sapo). Directions for Use: Take 20 drops in a glass of water three times a day after each meal. Restrictions: Keep in a cool, dry place. Keep out of reach of children.

- Axolotl (with leafy daikon) – Treats bladder infections, reduces irritation when urinating, improves bile flow, facilitates the expulsion of toxins, improves digestion, increases urine production, purifies the kidneys, eliminates small kidney stones, improves biliary function, eliminates sand, combats constipation, reduces cholesterol levels, treats fluid retention, useful in cases of hypertension, eliminates bacteria from the body

The ajolote (axolotl) is used medicinally (as well as culinarily). See Xochimilco and the Axolotl for more on this. The axolotl is critically endangered in the wild and has been on the Threatened Species list since 1997. Axolotls are protected under CITES, which regulates international trade of endangered species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and they are listed under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

The axolotl is not the only native animal used medicinally. Below is a supplement which also contains skunk (yes, you heard me right)

Axolotl Syrup reinforced with skunk 240ml | Aids in treatments to reduce inflammation of the respiratory tract. Ingredients : Higado de zorrillo (Skunk liver), Axolotl oil, Iodized radish, Balsamo del salvador, Honey, Gordolobo (Mullein), Anacahuite, Eucalyptus, Oreja de oso (Bear’s ear), Elderberry, Cardo Santo (Holy thistle), Menthol, Cebolla morada (Red onion), Garlic, Camelina, Guaje cirial, Cuatecomate, Vitamin C, Propolis, Echinacea

I go into the skunk as both food and/or medicine here….Skunkweed and the Skunk

The radish is used popularly to treat liver and respiratory illnesses (Paredes 1984) and are considered an excellent food remedy for stone, gravel and scorbutic (1) conditions (Castro-Torres et al 2012). The juice has been used in the treatment of cholelithiasis (2) as an aid in preventing the formation of biliary calculi.

- Scorbutic – pertaining to, of the nature of, or affected with scurvy. Scurvy may also be referred to as a severe vitamin C deficiency. Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding from the skin may occur. As scurvy worsens, there can be poor wound healing, personality changes, and finally death from infection or bleeding.

- Gallstones form when bile stored in the gallbladder hardens into stone-like material. Too much cholesterol, bile salts, or bilirubin (bile pigment) can cause gallstones. When gallstones are present in the gallbladder itself, it is called cholelithiasis.

To treat cholelithiasis one treatment protocol recommends…..”The expressed juice of white or black Spanish radishes is given in increasing doses of from 1/2 to 2 cupfuls daily. The 2 cupfuls are continued for two or three weeks. then the dose is decreased until 1/2 cupful is taken three times a week for three or four more weeks. The treatment may be repeated by taking 1 cupful at the beginning, then 1/2 daily, and later, 1/2 every second day.”

The antibiotic activity of various radish extracts have been studied extracts and the results corroborate the plants usage as reported in traditional medicinal practices.

The root’s juice showed antimicrobial activity against Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella thyphosa. The ethanolic and aqueous extracts showed activity against Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans. Aqueous extract of the whole plant presents activity against Sarcinia lutea and Staphylococcus epidermidis (Caceres 1987). Aqueous extract of the leaves showed antiviral effect against influenza virus. Aqueous extract of the roots showed antimutagenic activity against Salmonella typhimurium TA98 and TA100 (Gautam et al 2016). Ethanolic extracts of red radish seeds have also exhibited antimicrobial action with the gram-negative strains E. coli and S. typhimurium being the most sensitive strains to the extract (Jadoun et al 2016). Sevindik (et al 2023) also demonstrates that the white radish (Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus (L.) Domin) has “significant antimicrobial activity”.

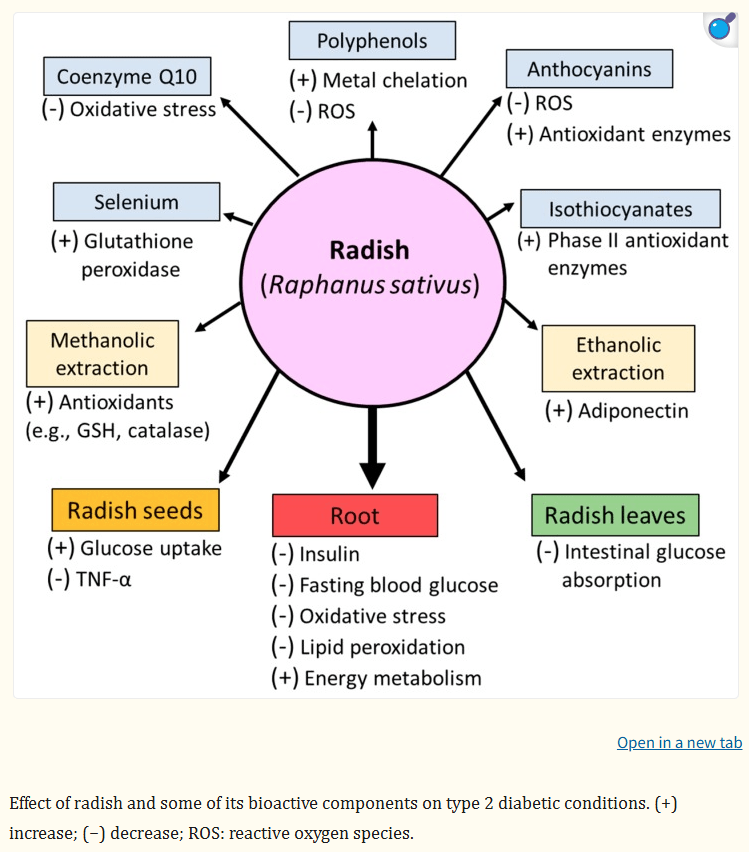

The antidiabetic nature of radish extracts is multifactorial and can address this particular illness by: (a) regulation of glucose related hormones, (b) prevention of diabetes-induce oxidative stress and (c) balancing the glucose uptake and absorption (Banihani 2014). Further study showed that radish root does indeed appear to have an antidiabetic effect and to be very beneficial in diabetic conditions. These antidiabetic properties may be due to its ability to enhance the antioxidant defence mechanism and decrease oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, improve hormonal-induced glucose haemostasis, promote glucose uptake and energy metabolism, and reduce glucose absorption in the intestine. (Banihani 2017)

Hepatoprotective effects of the radish extract have been recorded and studied. Even the crudest extracts such as powdered, dried leaves and simple water extracts have proven to be remarkably efficacious at protecting the liver. (Anwat et al 2006) (He et al 2019)(Hwang et al 2022)( Lee et al 2012)(Rahman et al 2020)

Studies have been made on the potential medicinal benefits of the leaves. One study (Lee et al 2023) demonstrated that RGP (1) had prebiotic and anti-adipogenic (2) effects. The prebiotic effects (3) of RGP were observed on probiotic strains, specifically Lacticaseibacillus, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium, as evidenced by increased prebiotic scores and concentrations of total SCFAs (4). RGP could modulate the bacterial growth of beneficial gut microbes and inhibit the differentiation and lipid accumulation of adipocytes. These findings suggest that RGP may have potential applications as a functional food ingredient for preventing or treating obesity and related metabolic disorders. During the study a significant decrease in lipid accumulation was observed, suggesting that RGP may effectively reduce obesity.

- Radish Green Polysaccharide – a hydroethanolic extract of the dried leaves

- Anti-adipogenic” refers to the process of inhibiting or preventing the differentiation of preadipocytes (fat precursor cells) into mature adipocytes (fat cells).

- With a prebiotic activity score significantly higher than inulin at the same concentration

- Short Chained Fatty Acids – SCFAs like acetate, propionate, and butyrate are produced when probiotic bacteria ferment indigestible carbohydrates in the colon. These SCFAs play a crucial role in maintaining gut health and have been linked to various health benefits.

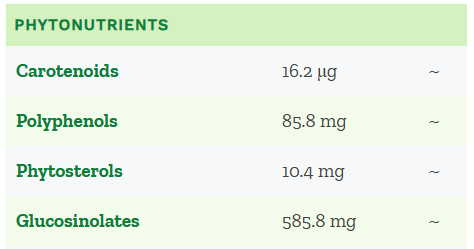

Ingestion of cruciferous vegetables (1) (of which our dirt apple is one) has significant benefits of chemoprevention (2) due to the presence of secondary metabolites, such as glucosinolates, which are highly noted for their anticancer properties.

- Cruciferous vegetables are a group of vegetables from the Brassica genus, known for their nutritional benefits and distinctive, often pungent, flavour. Examples include broccoli, cauliflower, kale, cabbage, Brussels sprouts, and bok choy. These vegetables are a good source of vitamins, minerals, fiber, and compounds called glucosinolates, which are believed to have potential health benefits, including cancer prevention. The term “cruciferous” comes from the Latin word “cruciferae,” meaning “cross-bearing.” This refers to the characteristic cross-shaped arrangement of the four petals in the flowers of these plants

- Chemoprevention is the use of medications or supplements to prevent cancer, particularly in individuals at high risk, and can be used to prevent, delay, or suppress the development or recurrence of cancer

Cruciferous flowers

Various cancers have been examined

- Colon Cancer (Peña et al 2022)

- Breast cancer (Kim et al 2011)

- Cervical (Lim et al 2020)

- Lung (Yang et al 2016)

- Prostate (Lim et al 2020)

These are only a few of the many hundreds (if not thousands – I didn’t check them all) of studies regarding this most humble vegetable. It is a remarkably medicinal plant.

According to the Commission E Monographs (1)….

- The German Commission E is a scientific advisory board of the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices formed in 1978. The commission gives scientific expertise for the approval of substances and products previously used in traditional, folk and herbal medicine. The commission became known beyond Germany in the 1990s for compiling and publishing 380 monographs evaluating the safety and efficacy of herbs for licensed medical prescribing in Germany. The monographs were published between 1984 and 1994 in the Bundesanzeiger; they have not been updated since then but are still considered valid.

- Raphanie sativi radix, also known as black radish root, is a drug monographed by Commission E and used in herbal medicinal products for the treatment of dyspeptic complaints and catarrhs of the upper respiratory tract.

- Rhaphani sativi radix promotes secretion in the upper gastrointestinal tract and also has a choleretic, antimicrobial and motility-promoting effect.

- The black radish root is used for dyspeptic complaints. It is also used for catarrhal infections of the upper respiratory tract.

- Rhaphanie sativi radix contains glucosinolates (mustard oil glycosides, including raphanin), allyl and butyl mustard oil. However, steam-volatile mustard oil and essential oil are only released after enzymatic cleavage. The mustard oils are responsible for the pungent taste of the root.

Furthermore, Raphanus sativus contains sinigrin , which shows anticarcinogenic effects in prostate cancer, possibly by inducing apoptosis (Nair AB et al. 2020) - The average daily dose of Raphani sativi radix is between 50 and 100 ml pressed juice. The application period should not exceed 6 weeks (Commission E).

- Adverse effects : There are no known adverse effects.

- Contraindication : If cholelithiasis is present, the patient should refrain from taking it.

Recent studies also suggest that the radish might be efficacious in the treatment of mental health disorders (particularly anxiety)

A preliminary study exploring the anxiolytic-like pharmacological effects of R. sativus and the most common inhibitory receptors involved in anxiety therapy has been conducted (Hernández-Sánchez et al 2023). Clinical therapy for anxiety is known to involve the use of drugs with GABAergic action (1), such as BDZs (2), mainly for acute attacks of generalized anxiety. This study, using an aqueous extract of R. sativus sprouts, noted that significant changes in the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor (3) blockade were observed in the open-field test, while it and GABAA/BDZs site receptor blockade have been suggested for anxiolytic-like effects of the extract.

- “GABAergic” refers to anything related to or involving the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, including neurons, synapses, and the system as a whole. Inhibitory neurotransmitters block or prevent the chemical message from being passed along any farther (It lessens a nerve cell’s ability to receive, create or send chemical messages to other nerve cells) by inhibiting neuronal firing and preventing the overexcitation of neurons. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glycine and serotonin are examples of inhibitory neurotransmitters.

- BDZs, or benzodiazepines, are a class of drugs that act as central nervous system depressants, used to treat conditions like anxiety, insomnia, and seizures, by enhancing the effects of the neurotransmitter GABA

- serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonists are more common for controlling chronic anxiety

Study continues.

Nutritional Data

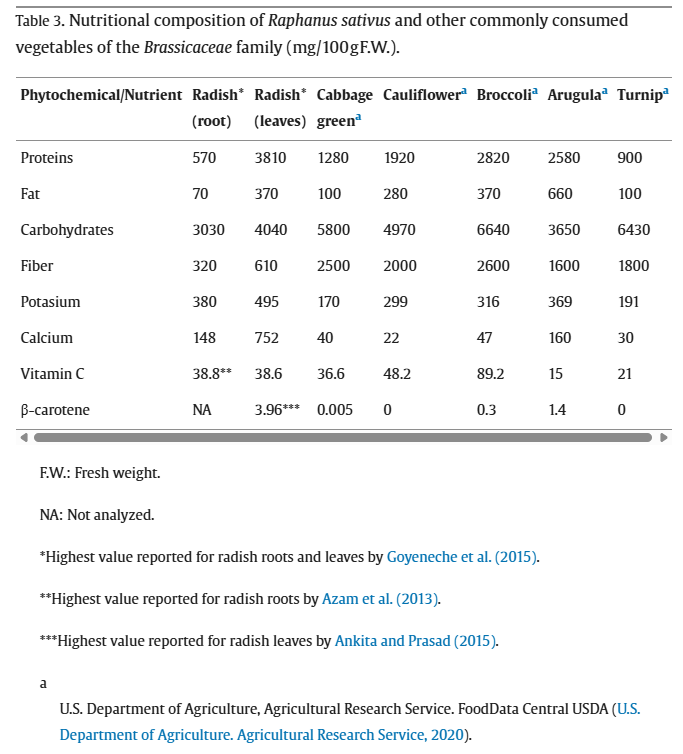

Are you one who throws away the leaves of the radish? It might be the wrong part to chuck out. According to the figures below the leaves dominate in every nutritional category except carbohydrates and fibre (which makes sense as fibre is usually carbohydrate in nature)

Some people may experience gas and bloating after consuming cruciferous vegetables due to this high fibre content.

I could find more detailed information on the root than the leaves (nutritionally speaking)

Serving size – 1 cup = 116g (4.1oz)

Cooking radish greens

Like any quelite (1), young radish leaves will be milder in flavour and more tender and are ideal for eating either raw or cooked. The mature leaves will be tougher and more bitter, so they work best when cooked which will help mellow their flavour. The bitter(ish) flavour might be something you seek though. The bitter herbs such as radicchio or endive are not as popular as once they were (which is a pity because they carry many health benefits)

Ther easiest way to utilize the greens is to simply fry them in oil and/or butter (after cleaning them of course – they have a tendency to gather and hold dirt – the main part eaten is a root vegetable after all). You can blanch older leaves briefly in boiling water first if you’d like. This will also remove some of the bitterness

Heat oil (or butter) in a pan and add a minced clove of garlic. Fry until fragrant. Add the greens and sauté for 2-3 minutes until they wilt. Then serve with a squeeze of fresh lemon juice and optional salt and pepper. Alternatively you can sauté radish tops and leeks and then add them to a frittata or R sauté the greens with garlic, butter, and olive oil and toss with crumbled feta cheese (or toasted pine nuts, or crumbled bacon etc etc)

References

- Aguiñaga Rodríguez, Luis & Salazar, Alejandro & Eligio, Jorge. (2024). Thyroactive Endogomines: Study of the Properties of Radish (Raphanus Sativus) as a Therapeutic Alternative in the Treatment of Hypothyroidism.

- Ahn M., Kim J., Hong S., Kim J., Ko H., Lee N.H., Kim G.O., Shin T. Black Radish (Raphanus sativus L. var. niger) Extract mediates its hepatoprotective effect on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatic injury by attenuating oxidative stress. J. Med. Food. 2018;21:866–875. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2017.4102.

- Aly T.A.A., Fayed S.A., Ahmed A.M., Rahim E.A.E. Effect of Egyptian radish and clover sprouts on blood sugar and lipid metabolisms in diabetic rats. Glob. J. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2015;10:16–21

- Anwar, Rukhsana & Mubasher, Ahmad. (2006). Studies of Raphanus sativus as Hepato Protective Agent. Journal of Medical Sciences. 6. 10.3923/jms.2006.662.665.

- Baenas N., Piegholdt S., Schloesser A., Moreno D.A., Garcia-Viguera C., Rimbach G., Wagner A.E. Metabolic activity of radish sprouts derived isothiocyanates in drosophila melanogaster. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:251. doi: 10.3390/ijms17020251

- Banihani S. Radish (Raphanus sativus) and diabetes. Nutrients. 2017;9:1014. doi: 10.3390/nu9091014.)

- Banga O. Radish, Raphanus sativus (Cruciferae). in Evolution of crop plants. (eds Simmonds N. W. ) 60–62 (Longman, 1976).

- Beevi S.S., Mangamoori L.N., Subathra M., Edula J.R. Hexane extract of Raphanus sativus L. roots inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in human cancer cells by modulating genes related to apoptotic pathway. Plant Food Hum. Nutr. 2010;65:200–209. doi: 10.1007/s11130-010-0178-0

- Caceres, A. (1987) Screening on antimicrobial activity of plants popular in Guatemala for the treatment of dermatomucosal diseases. J. Ethnopharm. 20, 223–237.

- Castro-Torres IG, Naranjo-Rodríguez EB, Domínguez-Ortíz MÁ, Gallegos-Estudillo J, Saavedra-Vélez MV. Antilithiasic and hypolipidaemic effects of Raphanus sativus L. var. niger on mice fed with a lithogenic diet. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:161205. doi: 10.1155/2012/161205. Epub 2012 Oct 3. PMID: 23093836; PMCID: PMC3471002.

- Fuks, D., Amichay, O., & Weiss, E. (2020). Innovation or preservation? Abbasid aubergines, archaeobotany, and the Islamic Green Revolution. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 12(2). doi:10.1007/s12520-019-00959-5

- Gautam, Satyendra & Saxena, Sudhanshu & Kumar, Sanjeev. (2016). Fruits and vegetables as dietary sources of antimutagens. Journal of Food Chemistry and Nanotechnology. 2. 96-113. 10.17756/jfcn.2016-018.

- Goyeneche, Rosario & Roura, Sara & Ponce, A.G. & Vega-Galvez, Antonio & Quispe, Issis & Uribe, Elsa & Di Scala, Karina. (2015). Chemical characterization and antioxidant capacity of red radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves and roots. Journal of Functional Foods. 16. 256-264. 10.1016/j.jff.2015.04.049.

- Gupta P., Kim B., Kim S.H., Srivastava S.K. Molecular targets of isothiocyanates in cancer: Recent advances. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014;58:1685–1707. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300684.

- Gutiérrez, Rosa & Perez, Rosalinda. (2004). Raphanus sativus (Radish): Their Chemistry and Biology. The Scientific World Journal. 4. 811-37. 10.1100/tsw.2004.131.

- Hameed, Abdul & Khan, Ikhtiar & Mahmood, Abid. (2013). Yield, chemical composition and nutritional quality responses of carrot, radish and turnip to elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide. Journal of the science of food and agriculture. 93. 10.1002/jsfa.6165.

- Hämeen-Anttila, Jaakko (2006). The Last Pagans of Iraq: Ibn Wahshiyya And His Nabatean Agriculture. Leiden: Brill.

- He Q, Luo Y, Zhang P, An C, Zhang A, Li X, et al. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant potential of radish seed aqueous extract on cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity and oxidative stress in mice. Phcog Mag 2019;15:283-9.

- Hernández-Sánchez, Laura & González-Trujano, María & Moreno, Diego A. & Vibrans, Heike & Castillo-Juárez, Israel & Dorazco-González, Alejandro & Soto-Hernandez, Marcos. (2023). Pharmacological evaluation of the anxiolytic-like effects of an aqueous extract of the Raphanus sativus L. sprouts in mice. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 162. 1-8. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114579.

- Hill, Robert : Bought of Robert Hill grocer dwelling at the 3 Angells in lumber streete the 26th July 1631 : Papers of the Winthrop Family, Volume 3 : 1631-07-26 : https://www.masshist.org/publications/winthrop/index.php/view/PWF03p48

- Hwang KA, Hwang Y, Hwang HJ, Park N. Hepatoprotective Effects of Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) on Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Damage via Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. Nutrients. 2022 Nov 29;14(23):5082. doi: 10.3390/nu14235082. PMID: 36501112; PMCID: PMC9737327.

- Jadoun J, Yazbak A, Rushrush S, Rudy A, Azaizeh H. Identification of a New Antibacterial Sulfur Compound from Raphanus sativus Seeds. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:9271285. doi: 10.1155/2016/9271285. Epub 2016 Oct 3. PMID: 27781070; PMCID: PMC5066007.

- Kim W.K., Kim J.H., Jeong D.H., Chun Y.H., Kim S.H., Cho K.J., Chang M.J. Radish (Raphanus sativus L. leaf) ethanol extract inhibits protein and mRNA expression of ErbB2 and ErbB3 in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2011;5:288–293. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2011.5.4.28

- Lee S.W., Yang K.M., Kim J.K., Nam B.H., Lee C.M., Jeong M.H., Seo S.Y., Kim G.Y., Jo W.S. Effects of white radish (Raphanus sativus) enzyme extract on hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Res. 2012;28:165. doi: 10.5487/TR.2012.28.3.165.

- Lee YR, Lee HB, Kim Y, Shin KS, Park HY. Prebiotic and Anti-Adipogenic Effects of Radish Green Polysaccharide. Microorganisms. 2023 Jul 24;11(7):1862. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11071862. PMID: 37513035; PMCID: PMC10385334.

- Lim, S., Ahn, JC., Lee, E.J. et al. Antiproliferation effect of sulforaphene isolated from radish (Raphanus sativus L.) seeds on A549 cells. Appl Biol Chem 63, 75 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13765-020-00561-7

- Manivannan A, Kim JH, Kim DS, Lee ES, Lee HE. Deciphering the Nutraceutical Potential of Raphanus sativus-A Comprehensive Overview. Nutrients. 2019 Feb 14;11(2):402. doi: 10.3390/nu11020402. PMID: 30769862; PMCID: PMC6412475.

- Mayerson, P. Radish Oil: A Phenomenon in Roman Egypt. Am. Soc. Papyrol. 2001, 38, 109–117.

- O’Bryhim, Shawn. “Catullus’ Mullets and Radishes (c. 15.18-19).” Mnemosyne, vol. 70, no. 2, 2017, pp. 325–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44507827.

- O’Donoghue K, Clapham A, Evershed RP, Brown TA. Remarkable preservation of biomolecules in ancient radish seeds. Proc Biol Sci. 1996 May 22;263(1370):541-7. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0082. PMID: 8677257.

- Paraskiewicz K. Persian dishes in the 13th century Kitāb al-ṭabīkhby al-Baghdādī. In: Michalak-Pikulska B, Majtczak T, Piela M, eds. Oriental Languages and Civilizations. Jagiellonian University Press; 2022:173-190.

- Paredes, S.D. (1984) Etnobotánica Mexicana: Plantas popularmente empleadas en el Estado de Michocán en el tratamiento de enfermedades hepaticas y vesiculares. Tesis Lic. México D.F. Facultad de Ciencias. UNAM.

- Pawlik A., Wała M., Hać A., Felczykowska A., Herman-Antosiewicz A. Sulforaphene, an isothiocyanate present in radish plants, inhibits proliferation of human breast cancer cells. Phytomedicine. 2017;29:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.03.007.

- Peña M, Guzmán A, Martínez R, Mesas C, Prados J, Porres JM, Melguizo C. Preventive effects of Brassicaceae family for colon cancer prevention: A focus on in vitro studies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022 Jul;151:113145. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113145. Epub 2022 May 25. PMID: 35623168.

- Pradeau, Alberto Francisco. “Pozole, Atole and Tamales: Corn and Its Uses in the Sonora-Arizona Region.” The Journal of Arizona History, vol. 15, no. 1, 1974, pp. 1–7. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41695162. Accessed 12 June 2025.

- Prasad, Kamlesh. (2015). Characterization of Dehydrated Functional Fractional Radish Leaf Powder. der Pharmacia Lettre. 7. 269-279.

- Rahman, Heshu & Bayz, Kashan & Hussein, Ridha & Abdalla, Azad & Othman, Hemn & Amin, Kawa & Abdullah, Rasedee. (2020). Phytochemical analysis and hepatoprotective activity of Raphanus sativus var. sativus in Sprague-Dawley rats. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 19. 1745-1752. 10.4314/tjpr.v19i8.25.

- Rosner, Fred (1995). “Oath of Asaph”. Medicine in the Bible and the Talmud: Selections from Classical Jewish Sources. KTAV Publishing House. pp. 182–186. ISBN 9780881255065.

- Emilie Savage-Smith, Simon Swain, and Geert Jan van Gelder With Ignacio Sánchez, N. Peter Joosse, Alasdair Watson, Bruce Inksetter, and Franak Hilloowala (2024) A Literary History of Medicine; Volume 3-2. Annotated English Translation : The ʿUyūn al-anbāʾ fī ṭabaqāt al-aṭibbāʾ of Ibn Abī Uṣaybiʿah ISBN 978-90-04-54560-1

- Sevindik, M., Onat, C., Mohammed, F. S., Uysal, İmran, & Koçer, O. (2023). Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of White Radish. Turkish Journal of Agriculture – Food Science and Technology, 11(2), 372–375. https://doi.org/10.24925/turjaf.v11i2.372-375.5983

- Shukla S., Chatterji S., Mehta S., Rai P.K., Singh R.K., Yadav D.K., Watal G. Antidiabetic effect of raphanus sativus root juice. Pharm. Biol. 2011;49:32–37. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2010.493178.

- Taniguchi H., Muroi R., Kobayashi-Hattori K., Uda Y., Oishi Y., Takita T. Differing effects of water-soluble and fat-soluble extracts from Japanese radish (Raphanus sativus) sprouts on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) 2007;53:261–266. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.53.261.

- Taniguchi H., Kobayashi-Hattori K., Tenmyo C., Kamei T., Uda Y., Sugita-Konishi Y., Oishi Y., Takita T. Effect of Japanese radish (Raphanus sativus) sprout (Kaiware-daikon) on carbohydrate and lipid metabolisms in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Phytother. Res. 2006;20:274–278. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1851

- Yang M, Wang H, Zhou M, Liu W, Kuang P, Liang H, Yuan Q. The natural compound sulforaphene, as a novel anticancer reagent, targeting PI3K-AKT signaling pathway in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016 Nov 22;7(47):76656-76666. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12307. PMID: 27765931; PMCID: PMC5363538.

Websites

- https://people.howstuffworks.com/culture-traditions/holidays-christmas/mexicos-night-of-radishes.htm (who referenced) https://www.mentalfloss.com/photos/516455/oaxacas-night-radishes) (who referenced https://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/oaxaca.html)

- Maimonides – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maimonides

- Mashed (image – radish eagle) – https://www.mashed.com/1318191/most-overrated-chain-restaurants-mashed-staff/

- Noche de Rabanos – https://www.mexconnect.com/articles/1395-december-in-oaxaca/

- Noche de Rábanos _ https://people.howstuffworks.com/culture-traditions/holidays-christmas/mexicos-night-of-radishes.htm (who referenced https://www.mentalfloss.com/photos/516455/oaxacas-night-radishes)(who referenced https://www.houstonculture.org/mexico/oaxaca.html)

- Posol – https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/posol

- Posole – https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/posole

- Pozole blanco –Pozolería Mi Tierra Culhuacán – https://godinchilango.mx/730-2/

- Pozole rojo (image) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Icf1f1laB50

- Pozole rojo – Jalisco – https://jaliscodemisamores.com/receta-de-pozole-estilo-jalisco-el-rey-de-todos-los-pozoles/

- Pozole Verde – El Pozole de Moctezuma – Colonia Guerrero Mexico City – https://culinarybackstreets.com/cities-category/mexico-city/2024/el-pozole-de-moctezuma-2/

- Pozolli – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/pozolli

- Pozón – https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/poz%C3%B3n

- Pozón – https://tureng.com/en/spanish-english/poz%C3%B3n

- Radish Danza – https://www.infobae.com/mexico/2023/12/23/la-noche-de-los-rabanos-en-oaxaca-que-es-y-como-surgio-esta-tradicion-navidena/

- Radish Flower (image) – https://indiabiodiversity.org/species/show/230913

- Radish Jesus – https://arkvalleyvoice.com/holiday-traditions-stretch-back-into-history-noche-de-rabanos/

- Radish plant (image and cultivation instruction) – https://gardenerspath.com/plants/vegetables/grow-radishes/

- Radish seeds – https://www.anniesheirloomseeds.com/

- Scholastic Kids Press (image – radish turkey) – https://kpcnotebook.scholastic.com/post/night-radishes