Although my primary focus is on masks from the Americas – particularly Mexico, where borders are as fluid as the plants that cross them – my collection spans a variety of cultures. While I’ve acquired a number of exceptional Mexican masks, I also collect traditional masks from Oceania and Asia. Living in Australia, I am fortunate to be immersed in a region rich with diverse artistic traditions, many of which are represented in my growing collection.

I have many masks from Indonesia (Balinese Barong masks specifically) but the latest to enter my collection is the mask of a Sri Lankan fire demon.

Barong (Balinese: ᬩᬭᭀᬂ, lit. ’bear’) is a panther-like creature and character in the mythology of Bali, Indonesia. He is the king of the spirits, leader of the hosts of good, and enemy of Rangda, the demon queen.

The battle between Barong and Rangda is featured in the Barong dance to represent the eternal battle between good and evil. I will likely go into these masks in another Post.

The battle between good and evil also plays a primary role in the mythos of Sri Lanka.

Sri Lankan ceremonial masks are grouped into distinct categories: Kolam (folktale), Sanni (healing), Pali, and Raksha (demonic). Each type has its own unique legend and purpose, often rooted in the island’s complex spiritual and mythological traditions.

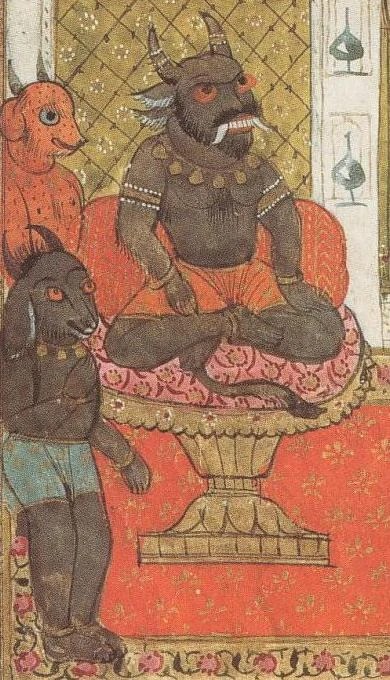

The legend of Raksha masks is linked to the Ramayana, an ancient Indian epic, hearkening back to a time when Sri Lanka was believed to be ruled by a race of Rakshasas, demons with the ability to shape-shift.

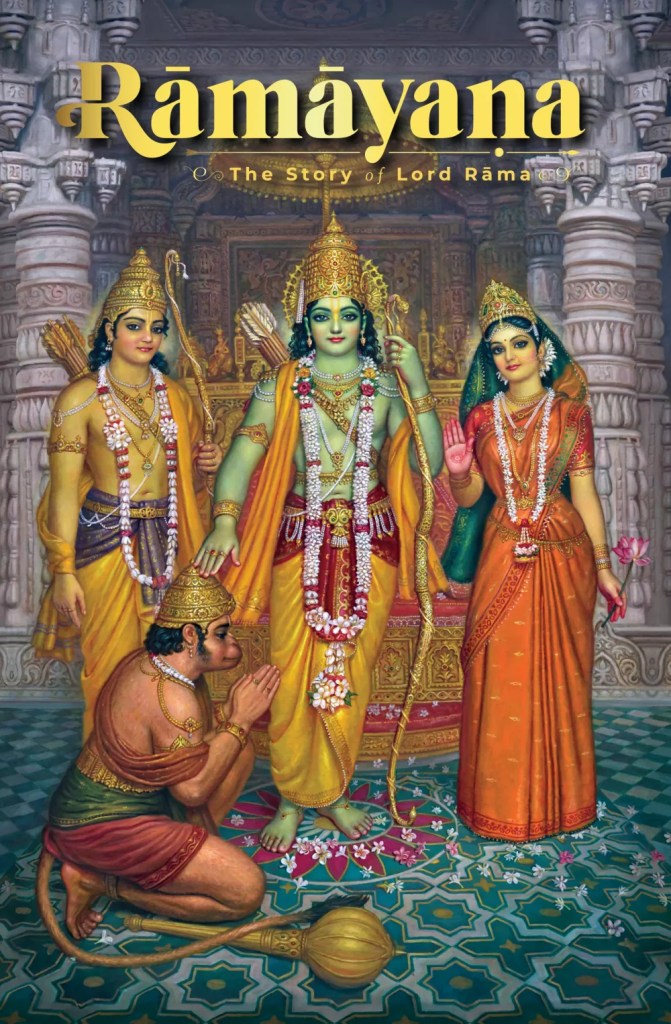

The epic narrates the life of Rama, the seventh avatar of the Hindu deity Vishnu, who is a prince of Ayodhya in the kingdom of Kosala and and follows his fourteen-year exile into the forest.

The Ramayana belongs to the genre of Itihasa (1), narratives of past events (purāvṛtta), which includes the epics Mahabharata and Ramayana, and the Puranas. The genre also includes teachings on the goals of human life. It depicts the duties of relationships, portraying ideal characters like the ideal son, servant, brother, husband, wife, and king. Like the Mahabharata, Ramayana presents the teachings of ancient Hindu sages in the narrative allegory, interspersing philosophical and ethical elements.

- In Hinduism, Itihasa-Purana, also called the fifth Veda, refers to the traditional accounts of cosmogeny, myths, royal genealogies of the lunar dynasty and solar dynasty, and legendary past events, as narrated in the Itihasa (Mahabharata and the Ramayana) and the Puranas. They are highly influential in Indian culture, and many classical Indian poets derive the plots of their poetry and drama from the Itihasa

Puranas : The Big Three : Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva

Puranas (truth be told I’ve never even heard of these guys)

Sorry. I couldn’t help myself. It’s an illness.

The Mahābhārata is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India revered as Smriti texts (1) in Hinduism, the other being the Rāmāyaṇa. It narrates the events and aftermath of the Kurukshetra War, a war of succession between two groups of princely cousins, the Kauravas and the Pāṇḍavas.

- Smriti texts are a category of Hindu scriptures that are considered to be based on human memory and tradition, as opposed to Shruti texts, which are considered divinely revealed. They include various works like the Dharmashastras, Itihasas (epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata), Puranas, and Agamas. Smriti texts are seen as interpretations and elaborations of the Vedic teachings, providing practical guidance on law, ethics, social conduct, and rituals. Agamas, specifically, focus on temple construction, daily worship rituals, and various philosophical and yogic practices.

These are the Sri Lankan masks in my collection.

To be fair (only to the masks I guess) ’twas the Naga who entered my collection first. The Peacock was second and, on the day I received the peacock, I was spun a yarn about the Naga (crowned with seven serpents, as mine was) being the mortal enemy of the peacock (which is true in a way I guess) and that these two masks were the antithesis of each other. As a result of this tale of conflict and balance (in a Batman/Joker kind of way) I placed them above two doorways, facing each other, at opposite ends of a hallway glaring mortally at each other. I have come to find that this story is not exactly correct (in the context of the masks anyway) and that the two can be valuable allies, both to you and each other.

I’m starting with the peacock first as I have memories over the years of living near and visiting gardens that had peacocks. They have a distinctive cry that can hang in the air and are very beautiful birds (delicious too I hear).

The Mayura Raksha

Once, a peacock helped the god Indra to escape the demonic king Ravana.

Ravana is the multi-headed demon-king of Lanka in Hindu mythology. With ten heads and twenty arms, Ravana could change into any form he wished. Representing the very essence of evil, he fought (and ultimately lost) a series of epic battles against the hero Rama, seventh avatar of Vishnu.

part of a Chhou dance costume, India, Bengal, Purulia District,

by Nepal Chandra Sutradhar, 2001

The peacock opened his tail and Indra hid behind it.

Grateful Indra said: Peacock, you will never be afraid of snakes and your tail will never be plain blue, but will have a hundred iridescent eyes, and when the rain falls you will dance with joy remembering our friendship.

Another legend says mayura, or the peacock, was created from one of the feathers of Garuda, a mythical bird in Hindu mythology and a carrier of Lord Vishnu.

I also find the parallels between the eagle/serpent imagery (a lot of which involves aquatic environments) quite interesting (and very mesoamerican)

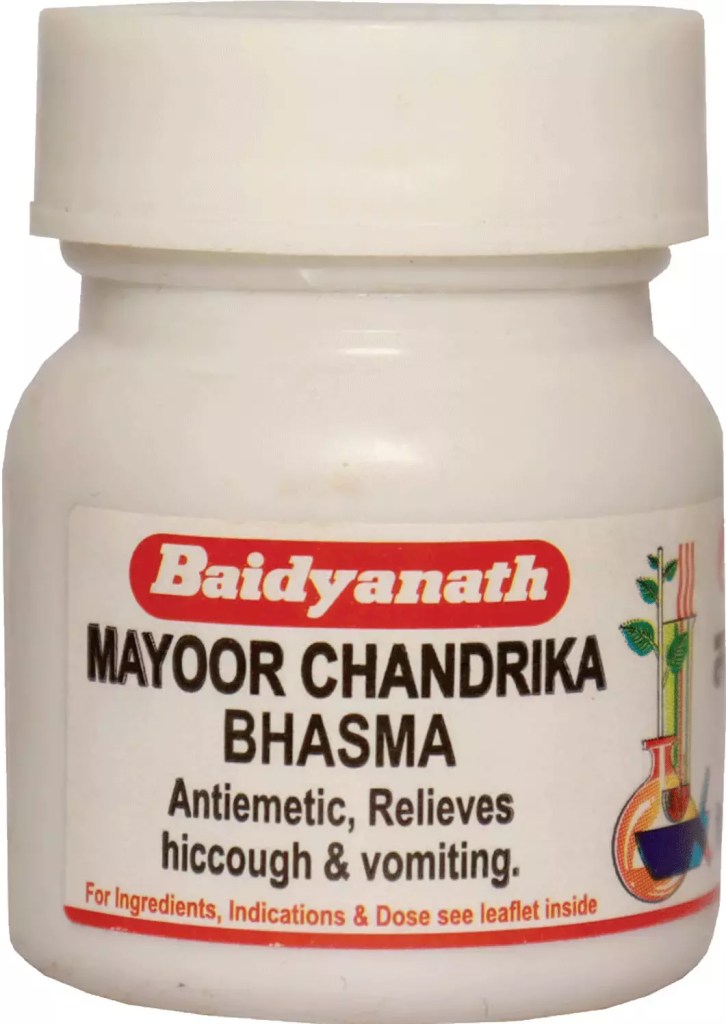

The peacock is an enemy of poisonous creatures, such as scorpions and snakes. The striking colours and tail-plumage represent the transformation of the poisons into the nectar of wisdom and accomplishment. It is believed that the peacock can give protection from venomous creatures and heal those afflicted by poison. This is actually quite interesting as a 2005 study (Murari et al) demonstrated that a folk remedy of applying a preparation made from the ash of peacock (Pavo cristatus) feathers had a neutralizing effect against snake venom enzymes responsible for local tissue necrosis.

Mayura Chandrika Bhasma is an ayurvedic medicine prepared from the feathers of a peacock in the form of ash (Bhasma). Mayura pankh or Peacock feathers are collected and the colourful central part of the pankh is separated. This colourful part is then burnt with Ghee (Clarified cows milk Butter) in a closed container under high “fire”. The ashes obtained after burning the peacock feathers is known as Mayura Chandrika Bhasma. This bhasma is touted for its antiemetic and antispasmodic properties and as a treatment for nausea and vomiting. It is also said to be beneficial in hiccup, cough and asthma.

The peacock is an important character in the Raksha ceremonial dance in Sri Lanka. The performance shows the struggle between a cobra symbolising demonic forces and a bird standing for positive influence. The Mayura (1) Raksha is believed to bring peace, harmony, and wealth, according to the superstition of Sri Lankan culture. The masks represent three beautifully feathered peacocks on the sides and top of the mask.

- Mayura (Sanskrit: मयूर Mayūra) is a Sanskrit word for peacock

The Mayura Raksha mask serves multiple purposes:

- Protection: Named after the Sanskrit word for “guardian,” it is believed to protect against negative energies and malevolent spirits, often used in rituals for blessings and safety.

- Peacock Representation: With its peacock motifs, symbolizing beauty and royalty, the mask embodies qualities like prosperity and abundance.

Possessing this mask will bring the owner peace, harmony and wealth.

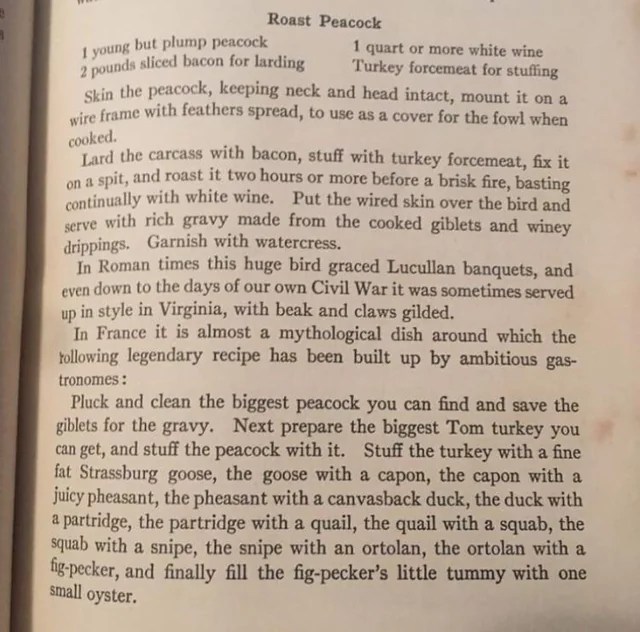

I wasn’t going to include a recipe for peacock but I came across this beauty and could not resist including it. You may have heard of the culinary mongrel known as a “turducken” (1) but this example of chimeric bastardry found in a 1920’s cookbook would give even Aulus Vitellius (2) conniptions.

- A turducken is a cranberry & chestnut stuffing stuffed in a fully deboned whole free range chicken, stuffed inside a fully deboned whole free range duck, which is then stuffed inside a partially deboned whole free range turkey. Each slice contains portions of chicken, duck and turkey with cranberry and chestnut stuffing in between the layers.

- The Roman Emperor Aulus Vitellius is most remembered for his gluttony. Historical accounts, particularly those by Suetonius and Tacitus, portray him as excessively devoted to luxury and feasting, with a particular fondness for elaborate and expensive dishes. Vitellius was known for inventing the “Shield of Minerva,” a dish with rare and costly ingredients like pike livers, pheasant and peacock brains, flamingo tongues, and lamprey milt.

The recipe. I think its moniker “Roast Peacock” falls somewhat short when naming this dish.

Strap in, it’s a hell of a journey

First get one of these, then………………(in reverse)

This by itself would be bad enough………..but it’s not over

Not even close to being over……..

Holy Crap. When is this going to end……….??

Yikes

If you ever make this dish then please let me know (and send photos)

Ginidal Raksha

This is my new mask. The third of my Sri Lankan Rakshasa. This is a visually stunning mask that my photography does no justice to at all.

This Fire Demon (Devil) mask, also called as Ginidal Raksha (1) represents the demon of fire who projects anger towards all evil in the world. It is believed that this mask, representing fire, strength, and power and embodying the fierce and protective nature of the Rakshasas symbolises the burning away of negativity and stands as a guardian of good energy, it was once used in ancient healing rituals to chase away evil spirits and illness.

- also Gini Raksha or Gini Yak Muhunu

Hanging the mask in your home will work as a good luck charm and bring protection to your household. It is also said that having possession of this mask will “drown off” your enemies and, bring friendship and harmony. Other folklore says the Gini Raksha mask is representing the emotion of anger which is why it includes colours such as red, black, and white.

Naga Raksha

The “Naga” part of the name refers to the cobra, a creature often associated with protection, power, and good fortune (up until now its been almost entirely negative so this is a nice change)

Naga Raksha, or Cobra Mask is a very prominent representation of Sri Lankan masks. This masks portrays a demon who could transform into a King Cobra

The ‘Naga Raksha’ (Demon King Cobra) mask, which is one of the most popular traditional Sri Lankan masks, is a blend of the Naga and a Raksha. The Naga (king cobra) is a commonly seen animal in ancient Sinhalese (one of the main ethnic groups of Sri Lanka) art. It is also a sacred animal as well as a feared animal in local mythology and folklore.

There is more than 1 kind of Naga

Naga, Dwi Naga and Ratnakutha Raksha Masks

The three types of Naga (snake) mask have similar meanings. These masks are used to protect against all types of evil spirits.

- Naga Raksha – The Naga presents well-defined visual symbols, each with its own meaning. The snake hood represents divine knowledge, spiritual protection and immortality; the bulging eyes were designed to ward off evil and intimidate undesirable presences; the vibrant colours follow a chromatic code that refers to vital energy, spiritual strength, the process of purification and the dimension of latent danger; the extended tongue symbolizes constant vigilance, assertive communication and the revelation of truth without fear.

- Dwi Naga Raksha – translates to “Two Cobra Demon” or “Twin Cobra Raksha” in Sinhala. The mask symbolizes protection from evil spirits and is believed to bring good fortune.

- Rathnakuta – this one is a bit harder to pin down. Ratnakuta is a Hindi boys name meaning “Treasure of Precious Stones” and, in Buddhism, it specifically denotes a collection of 49 Mahayana sutras, often translated as “Heap of Jewels”. In reference to the mask I have often seen it translated as “Red mask” and, if you check the images above, there is confusion between the Rathnakuta Raksha and the Naga Raksha (Snake Demon) mask (they look pretty much the same yes?) but they are distinct from each other. The Rathnakuta Raksha symbolizes power, energy, and protection.

The masks portray the snake demon who could transform into a King Cobra.

The demon King Cobra captured and enslaved its enemies. Only Gurulu Raksha, the great bird of prey, was able to drive the Nagas away.

Leyenda de las máscaras (Legend of the Masks)

Raksha masks are used a lot in festivals and cultural dances. Raksha means “demon” and the masks are apotropaic (1). They are painted in vibrant colours, with bulging eyes and protruding tongues and they depict various types of demons. Raksha masks are the final aspect of the Kolam ritual (1).

- having the power to avert evil influences or bad luck.

- Kolam is a form of traditional decorative art that is drawn by using rice flour as per age-old conventions. A kolam or muggu is a geometrical line drawing composed of straight lines, curves and loops, drawn around a grid pattern of dots. It is widely practised by female family members who draw kolams at the entrances to their homes every day at the break of dawn. The art is ephemeral as the drawings get walked on throughout the day, washed out in the rain, or blown around in the wind and new ones are made the next day. Each morning before sunrise, the front entrance of the house, or wherever the kolam may be drawn, is swept clean, sprinkled with water, thereby making for a flat surface. The kolams are generally drawn while the surface is still damp so the design will hold better. The act of drawing kolams can be a meditative and mindful practice, fostering creativity and enhancing focus and concentration. They are primarily meant to bring prosperity and good luck, and to welcome the Hindu goddess of wealth, Lakshmi. Additionally, they serve as a form of aesthetic decoration and an invitation to positive energy, while also potentially warding off evil spirits.

This art of daily creation of kolam drawings reminds me of the Balinese practice of Canang sari. These are small offerings of fruits, flowers and incense artistically arranged in small banana leaf receptacles. The Balinese provide these offerings (and others) to help maintain balance between the Hindu Gods and the spiritual realm and the mortal realm of people. The canang sari is the, by far, the most common offering and you can often see it on the floor outside of houses and businesses during the day. Offerings are expected to be as beautiful as possible because that beauty is meant to delight the gods themselves.

“Whoever offers Me with devotion a leaf, a flower, a fruit, or water, I delightfully partake of that item offered with love by My devotee in pure consciousness.” Bhagavad Gita: (ix:26)

It is Balinese women who create these devotions and the ability to make them well is considered an absolutely essential skill.The skill is called “mejejaitan” and without it, a woman might find it difficult to find her place in society.

Balinese Hinduism stresses the importance of balance so the Balinese don’t just make offerings to “good gods” but they also make them for the gods of negative forces too. This to ensure that they not only encourage good forces to work for them but also to appease the negative ones so that they don’t work against them.

The Kolam masks are a tribute to the Rakshasas, a race that earlier ruled Sri Lanka and could assume 24 different forms. But only a few of these forms are performed, some of which are Naga Raksha (cobra mask), Gurulu Raksha (Mask of the Bird), Maru Raksha (Mask of the Demon of Death) and Purnaka Raksha.

Various depictions of rakshasa.

The origin of these masks is linked to the origin myth of the Kolam dance and both were born due to the cravings of a pregnant woman.

This woman, the wife of king Maha Sammatha (1), became pregnant and craved entertainment, she desired to see dances accompanied, with jokes and humour.

- King Maha Sammata Manu was born in the beginning of the world in Jambudvipa, the only habitable continent on earth. He was elected by the people to be their king, and he ascended to the throne with the title “Maha Sammata” or “The Great Elect.” As king, he established the order of the city-state, defined the various duties and offices of the state, and set the boundaries of the armies for their protection.

The cravings of the queen could not be satisfied as there was no one who knew about dances accompanied with humour at that time. This made life very difficult for the king and the whole royal assembly. The king took immediate action and decreed that if there was anyone who could fulfil the craving of the Queen he should venture or come forward immediately. His exhortations were in vain and there was no-one who could help. The king became very worried and was overcome by melancholy.

At this juncture, the God Sakra, the incumbent of the two heavens, seeing this sorrow summoned Vishwakarma, (1) the Lord for dance and creation in the heaven , and instructed him to remedy the situation.

- Also vishvakarma, Vishwakarma. Vishvakarma or Vishvakarman (Sanskrit: विश्वकर्मा, lit. ’all maker’, IAST: Viśvakarmā) is a craftsman deity and the divine architect of the devas in contemporary Hinduism. In the early texts, the craftsman deity was known as Tvastar and the word “Vishvakarma” was originally used as an epithet for any powerful deity. However, in many later traditions, Vishvakarma became the name of the craftsman god

Vishmakarma placed masks and books containing the way of singing the songs in the royal garden. The royal gardener came across these wooden masks and books containing the texts which highly delighted the king who summoned some citizens and ordered them to perform the dances. This not only fulfilled the pregnancy craving of the queen, but marked the origin or birth of a new form of dance called Kolam and the folk art of masks.

Basically there are three categories of mask dances that are identified in Sri Lanka. These are the Raksha (Demon) dances, Kolam (Folktale) dances and Sanni (Devil Dance) dances. Kolam masks are used to represent various officers and people in the society in performing the Kolam drama with singing and jokes. Raksha masks are believed to be used to ward off evil or as an aid in festivals like Gam madu or Devol madu. The third type, Sanni masks are mostly used in Thovil and witchcraft healing ceremonies and worn by an edura (exorcist).

First category is the Raksha Mask

According to legends, Sri Lanka was earlier ruled by a race called Rakshasas whose king was Ravana of the Ramayana. Rakshasas could assume various forms.

Although they have 24 forms of Rakshasas only few are performed in Kolam dance; some of which are

- Naga – Cobra that captures its enemies and makes them slaves.

- Gurulu – Hawk or Eagle that rescues the captives from the Naga.

- Maru – Demon of death.

- Ginidal – Fire Devil The Ginidella Raksha mask is a Raksha mask which is means its job is to ward off evil. This mask is representing the emotion anger which is why the colors are red, orange, and yellow. The patterns on the ears are warding off all evil. The patterns on the ears and the face really draw your attention which the Sri Lankan people found really important.

- Mayura – The Peacock mask is supposed to bring peace and harmony, therefore the bright beautiful colors white, and blue. A peacock is also know to bring peace and harmony. This mask also wards off evil spirits and ghosts.

- Dwi Naga – The Naga Raksha mask, also known as the Snake Demon, uses a lot of colors and patterns to it. The most noticeable and attractive pattern is the hair which is shaped into cobras, therefore the name Snake Demon.

- Mal Guru – Flowery Eagle that brings fame and fortune

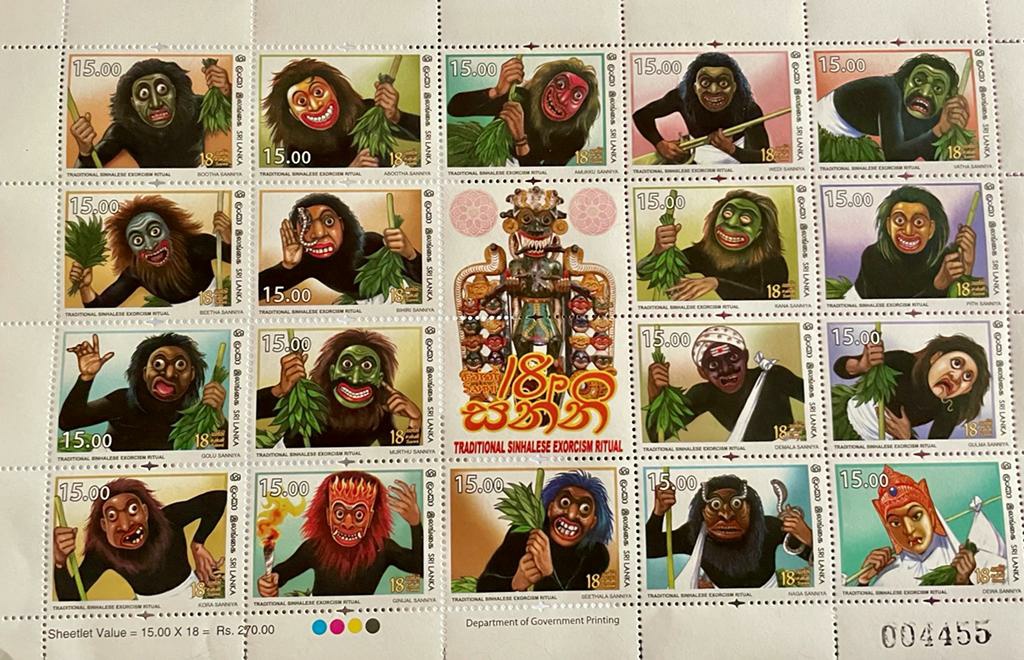

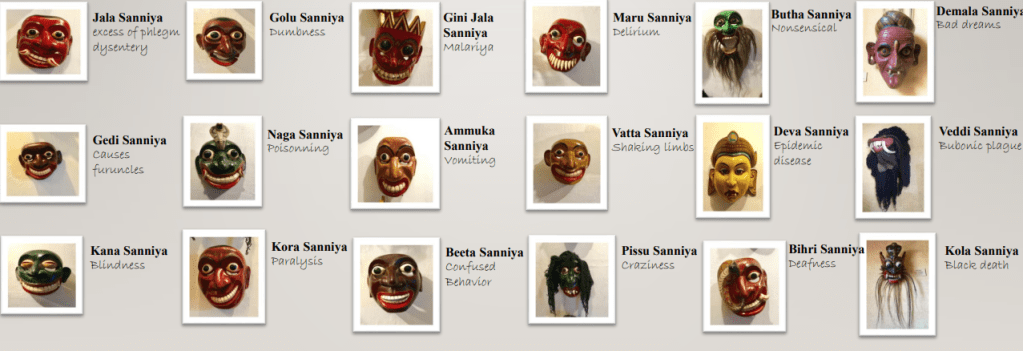

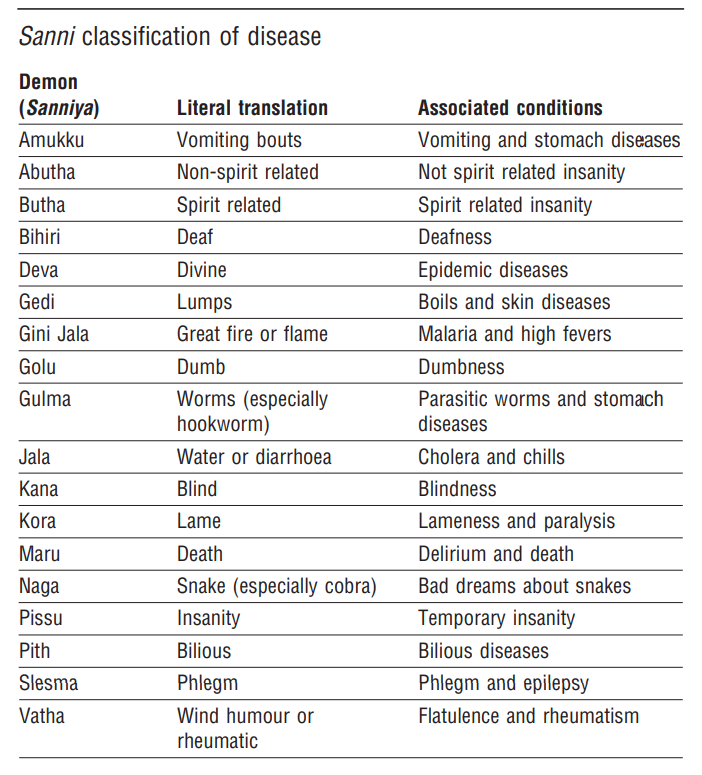

Second category : The Sanni Mask (used for curing specific illnesses). There are at present eighteen (18) sanni masks. The sanni masks are not very elaborate and are smaller in size. They are generally in the form of a face making grotesque expressions.

It is common in Sri Lanka for families to turn to an exorcist when a loved one is ill. The Sanni Yakuma is a sacred Sinhalese dance that is performed by an exorcist with the intention of curing certain diseases. By performing the devil dance, the exorcist seeks to subdue and expel them back to the demon world, thereby curing the human that is suffering from an ailment. The Sanni masks are designed in such a way that they become grotesque demonic representations of certain illnesses.

One of the raksha masks, Maha Kola, comprises the entire pantheon of eighteen sanni devils in one mask tied together by intertwined serpents. This mask is also assigned the same task of cleansing the sick.

Maha Kola is the boss of 18 demons of illness that are represented in the Sanni “Devil” Dance. Holding victims in his hands and mouth, Maha Kola is surrounded by snakes and by the 18 Sanniyas – the demons of blindness, cholera, boils, and other pestilences, each of whom is given its own mask. As the curing ceremony proceeds, a ritual specialist propitiates the appropriate demons on behalf of the patient and his family. When done, the demons are dismissed and the area is ritually cleansed of any lingering bad influences

The illnesses attached to each sanniya

The third category is the Kolam Mask used in the kolam play performances. These masks depict the characters of the play, which are generally from the folk tales and show characters such as kings and queens with elaborate head gear. There are other characters as well, of which one is of the serene faced Naga Kanya, a serpent demi god.

In Hindu mythology, Nagas are serpentine spirits who reside in the underworld, protecting and offering the teachings of the Mother Goddess. They are said to guard all esoteric and mystical teachings, offering them only to those who come humbly to receive. In turn, they offer protection and gifts to the seeker

Naga Kanya — also known as Nag Kanya or Naag Kanya — snake of the rainbow, daughter of the serpent, serpent maiden, maiden of snakes, guardian of treasures, benevolent goddess of the three realms.

Typically depicted as a half-human, half-serpent being, sometimes with multiple snake heads, Naga Kanya is a protective deity, often guarding temples and warding off evil spirits. She embodies the connection between the human and natural realms and is seen as a source of wisdom linked to esoteric and mystical teachings. In her serpent form she is associated with fertility and the nurturing elements of nature

The masks used in kolam drama can be divided into three categories;

- Masks which represent human beings: King, Queen, Hewa, Jasa, Lenchina, Suransina, Arachchi, Mudali, Chencha, Liyanappu

- Over-realistic masks: Narilatha, sandakinduru, gurulu, surabawalliya, giridevi, Raksha

- Animal masks : Lion, tiger, fox, dog, eagle

Ana Bera Mask – Mirissa Udupila Tradition

King Maname Mask – Mirissa South Kolam Tradition

Queen Maname Mask – Ambalangoda Tradition

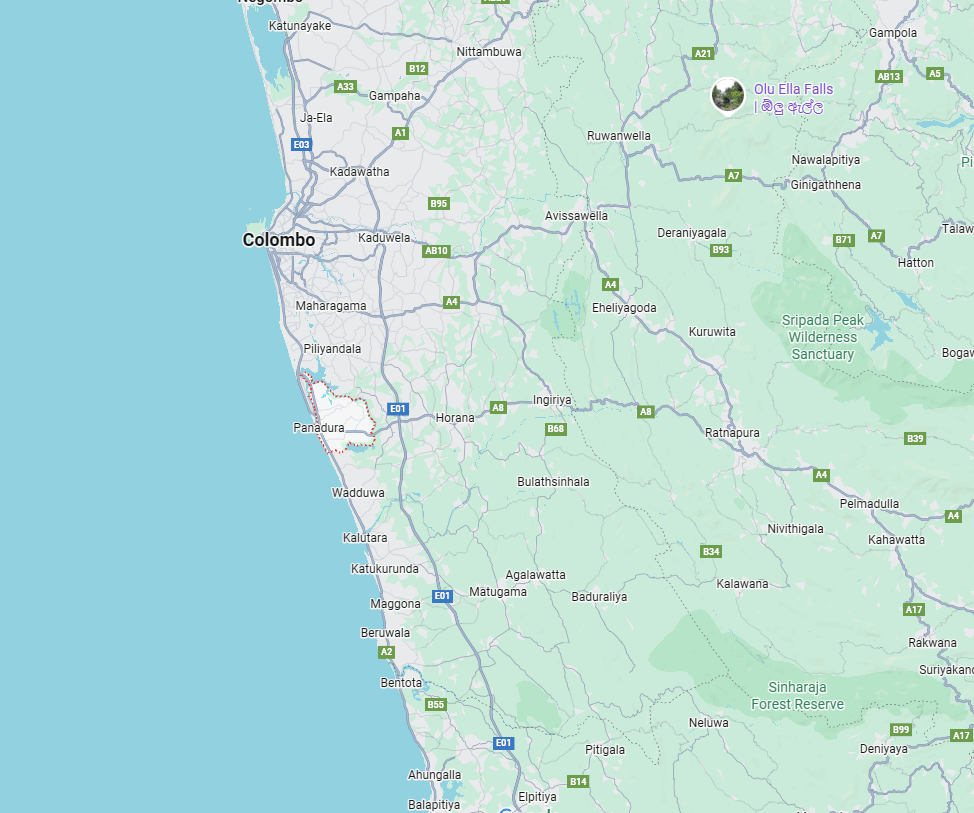

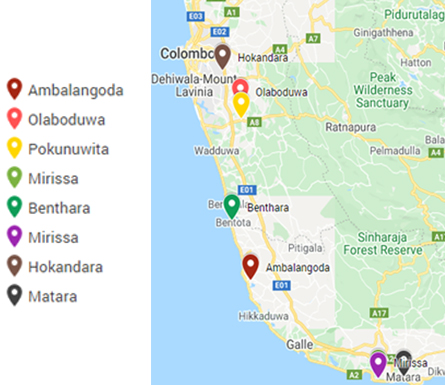

The birthplace of kolam is the southern maritime area.

The Kolam drama was mainly popular in the maritime areas from Panadura to Tangalle, and suburbs in the interior of the country. Ambalangoda, Benthara, Mirissa, Matara, Rayigam korale olaboduwa, Hokandara, and Siyane Koralaye Gampaha..

It is fair to assume that the places where kolam masks were crafted were also the places where it was originated.

At present, there are skilled artists who make masks, paint, practice drama, play drums, and dance. This is mainly because Kolam drama is linked with the low country dance tradition.

The making of these masks is a dying art.

In the olden days the wood of the tree ‘Din’ (1) which grew in the banks of rivers, had been used to carve masks.

- The term “Din tree” in Sri Lanka likely refers to the Hora tree (Dipterocarpus zeylanicus), also known as “Diyana” or “Diya Naa”. It’s a large tree native to Sri Lanka and is significant in Buddhist traditions, particularly as a tree associated with a past Buddha. The wood is strong and durable, used in construction and various other applications

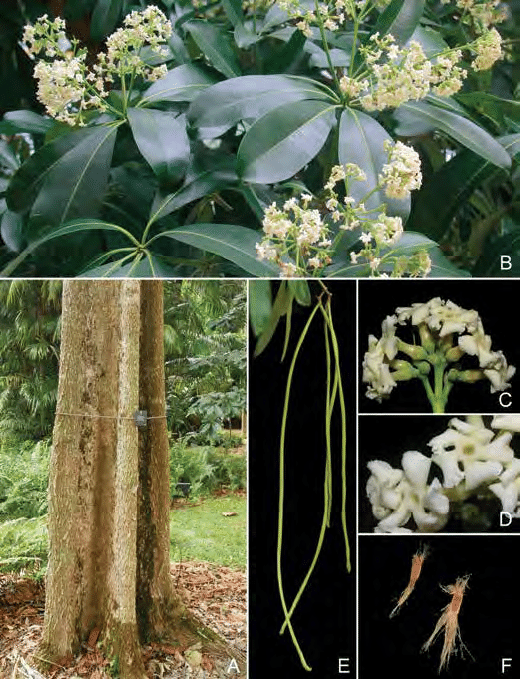

As the wood of the Din tree was not durable or long-lasting, wood of the VelKaduru or Rukattana (1) was used.

- Also called – Ruk-aththana (Devils tree), Eth-mada (Sinhala); Elilaippalai, Mukam pelai (Tamil)

Before being able to carve these masks the craftsmen was required to perform a number of rites. Before felling down the Kaduru tree they would look for an auspicious time for the project. They would offer flowers and lamps to the “incumbent deity” of that particular Kaduru tree and plead with him to move to some other tree. It was only after this that they could begin cutting down the tree – a reminder of the reverence with which nature and artistry are intertwined in these traditions.

The kaduru tree, Alstonia scholaris is an evergreen tree in the oleander and frangipani family Apocynaceae. Its natural range is from Pakistan to China, and south to northern Australia. It is a toxic plant but is used traditionally for myriad diseases and complaints.

Alstonia scholaris (Middleton et al 2019)

A. Trunk.

B. Leaves and inflorescences.

C. Inflorescence.

D. Corolla from the front.

E. Fruit.

F. Seeds.

Another wood commonly mentioned in mask making is that of the Erebadu tree (1). This tree, Erythrina variegata is a relative of the Colorin tree used in Mexico for its edible flowers (2).

- also called Coral Tree, Indian Coral Tree, Thorny Dadap, Lenten Tree, Tiger claw

- Las Flores Comestibles : Edible Flowers : Colorin

More often than not it is the wood of the VelKaduru (1) tree used in the carving of of these low country traditional masks. This tree which grows mostly in marshy lands can be seen abundantly in the proximity to paddy fields.

- also vel kaduru, welkaduru or just kaduru

The ancestors of todays mask makers realized through experience that the wood of Kaduru tree (1) was most suitable as it was light, convenient to carve and it was easy to dance whilst wearing masks made of its wood (2). The wood of Kaduru was not used for any household purposes, not even as firewood because it was believed that the pots and pans may burst and crack.

- Strychnos nux-vomica

- The tree is also believed to have mystical powers, and masks carved from it are thought to possess protective or transformative qualities.

Kaduru wood from the Strychnos nux vomica tree is a very light timber and is suitable for production of masks as properly seasoned wood (1) has a distinctive softness and can be easily carved using a chisel. Before carving masks, logs of wood are dried in the sun for some time and sawn into wood bars of suitable sizes to make masks.

- Cure the wood for seven days over a smoky hearth to protect it from insect attacks.

As the trunk of the Kaduru tree is covered with a thick milky bark, the first thing they do is to remove it. After the log of wood dries up in the gentle breeze it is cut into the necessary and appropriate size.

According to the Ämbum Kavi (1) special measuring tools are used to get the appropriate dimensions, namely measuring by eyesight, measuring with fingers, by cubit or 18 inches length etc. Akshi Manaka or measuring by eyesight means observing with the eyes and preparing the measures. Anguli Manaka means measuring by using the fingers.

- Ämbum Kavi refers to verses (or “kavi”) found on Sri Lankan masks, particularly those used in traditional rituals and performances. These verses, also sometimes referred to as “embunkavi”, detail the prescriptive formulae or instructions related to the mask’s design, function, or the rituals it is associated with. These verses are often carved directly onto the mask itself..

Colour had an immense importance and there are prescribed color-schemes or masks. The older masks are found in the colour or red, yellow, black, white and sometimes a dark green obtained from mixing yellow and black. Blue was used very rarely.

Hinduism does not approve of friendship with Rakshashas but Sri Lankans manage to please both Gods and demons preferring not to get involved in epic battles of good and evil but quietly enjoy humble gifts of destiny instead.

The traditions surrounding these masks are not merely decorative—they are storytelling devices, spiritual tools, and cultural heirlooms. With each addition to my collection, I am reminded that while mythologies may vary, the human desire to understand and shape the forces around us remains remarkably consistent.

References

- Bailey MS, de Silva HJ. Sri Lankan sanni masks: an ancient classification of disease. BMJ. 2006 Dec 23;333(7582):1327-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39055.445417.BE. PMID: 17185730; PMCID: PMC1761180.

- De Silva, Danushi. (2019). THE FACE TO FACE COMMUNICATION TRADITIONAL MASKS OF SRI LANKA History, functions and present use. 10.13140/RG.2.2.18165.63204.

- De Silva Malliya Wadu Arosh Chaminda (2023), An Investigation of the Aesthetic Principles Underlying the “Maha Kola Sanniya” in Sri Lankan Mask-Making Tradition, 6th International Conference on the Humanities (ICH 2023), Faculty of Humanities, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. P181

- Middleton, David & Rodda, Michele. (2019). Apocynaceae. 10.26492/fos13.2019-05.

- Murari, S. K., Frey, F. J., Frey, B. M., Gowda, T. V., & Vishwanath, B. S. (2005). Use of Pavo cristatus feather extract for the better management of snakebites: Neutralization of inflammatory reactions. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 99(2), 229–237. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.027

Webpages

- A manuscript from the Mewar Rāmāyaṇa depicting Rāma slaying Rāvaṇa. – By Scribes and painters employed by the Kingdom of Mewar. – The Mewar Rāmāyaṇa, British Library., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=130417975

- Ana Bera Mask – Mirissa Udupila Tradition – https://arts.pdn.ac.lk/afcp/kolansl.php

- Balinese flower offering ritual in the morning – By Okkisafire – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50279712

- Balinese wooden statue of Vishnu riding Garuda, Purna Bhakti Pertiwi Museum, Jakarta, Indonesia. – By Gunawan Kartapranata – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11353849

- Demon King Ravana mask – https://www.nms.ac.uk/discover-catalogue/celebrations-and-festivities-get-to-know-ravana-the-ten-headed-demon-king

- Goda Kaduru (image) – https://medicine.kln.ac.lk/depts/forensic/images/LearningMaterials/Extendedversion_CommonPoisonousPlantsSL.pdf

- King Maname Mask – Mirissa South Kolam Tradition – https://arts.pdn.ac.lk/afcp/kolansl.php

- Mayura Raksha Mask – https://au.lakpura.com/products/mayura-raksha-mask

- Maha Kola mask – https://www.historiskmuseum.no/english/exhibitions/exhibitions-archive/masks-for-life-and-death/sanni/

- Naga Kanya – The Guardian Goddess of the Three Realms – https://himalayanmartonline.com/naga-kanya/

- Nâga Rassa Kolam dancer – https://suriyakantha.org/en/article/kolam-mask-n%C3%A2ga-rassa

- Naga Raksha Mask – https://au.lakpura.com/products/naga-raksha-mask

- Queen Maname Mask – Ambalangoda Tradition – https://arts.pdn.ac.lk/afcp/kolansl.php

- Raksha masks – https://srilankaphotographynet.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/737/

- Ravana (history) – https://www.worldhistory.org/Ravana/

- Strycnhos tree bark (image) – By Vinayaraj – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22373581

- The art of mask – https://ceylontoday.lk/2022/10/29/the-art-of-mask/

- The Many Faces of Sri Lanka: A Culture of Mask Making – https://beyondthewesterngaze.com/2020/08/06/the-many-faces-of-sri-lanka-a-culture-of-mask-making/

- The Queens Cravings – https://www.ceylondigest.com/3264-2/

- Tracing the Significance of Kolams – https://brownhistory.substack.com/p/tracing-the-significance-of-kolams