Xochipilli is one of the more benign figures (sacrificially speaking) in the pantheon of mesoamerican forces. Xochipilli has been linked to (and worshipped as) in various guises as the young god of the dawn (1) (and also the setting sun) (2), a god of vegetation (most notably of flowers but also intoxicating plants and the sprouting seed) a god of games, song, dance, poetry and frivolity, a force of fertility, the patron of cacao, and in more modern interpretations has been usurped as the “god of homosexuality”, in particular gay men (3).

- As Piltzintecuhtli Xochipilli is the (young) god of the rising sun : the solar energy that fosters vital force in all creatures, that produces abundant, leafy, beautiful vegetation. Solar vital force that favours spring, life, in its most beautiful expression. (APROMECI)

- I have seen reference to Xochipilli (in particular a song/hymn) which refers to him as being “Priest of the sunset, Lord of the Twilight” (I am seeking more reference on this one though). There is also other reference to his places of worship (particularly that of Xochipilia) being at the entrance to a cave. These entrances are symbolic of doorways to the underworld or Mictlan. This symbolism refers back to the sprouting seed and how it emerges from the darkness of the underworld and enters the realm of the Sun. See Xochipilli : A Force of Nature for a little more on this. It is also briefly elaborated upon in Xochipilli. The Symbolism of Enrique Vela

- this particular reclassification of Xochipilli seems to be a result of the phenomena (a new one to me) of “colonisation from within”. I go into more detail on this further into the Post under the section Modern artistic representations : Queer iconography

Over the centuries and into the modern day Xochipilli has been, and continues to be, represented and worshipped (1) in a number of guises. This Post will illustrate a brief history of these representations.

- for more information of the expression of veneration of Xochipilli as it is occurring now please see Xochipilli : A Force of Nature

Xochipilia : The Place of Xochipilli

Mascaras

The Mask of the God.

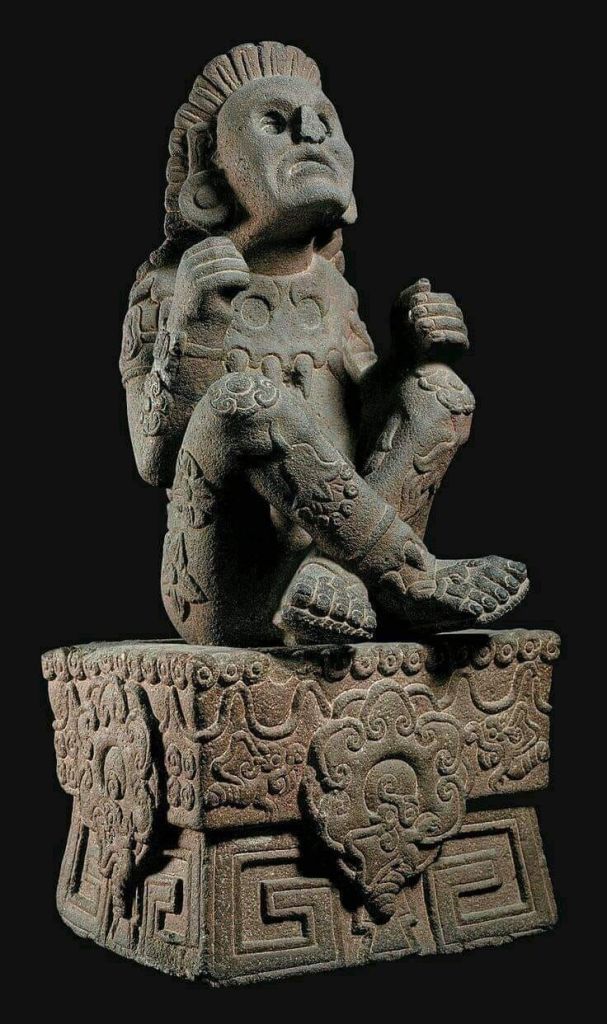

Masks play a large role in Aztec culture (and Mexican culture in general – read The Labyrinth of Solitude by Octavio Paz) and beings such as Xipe Totec wear not only masks but entire suits of skin flayed from sacrificial “victims”. There is suggestion that the Tlamanalco statue of Xochipilli (more on this image in a bit) depicts him as wearing a mask (possibly) of flayed skin. I examine this in Xochipilli. The Prince of Flowers

The above image is often referred to as being Xochipilli, likely due to the nasal ornament known as a yacapapalotl (yacatl = nose : papalotl = butterfly). It is of Teotihuacan origin. I go into more detail on this mask in my Post….Mascara de Xochipilli?

Archaeological examples of the yacapapalotl or nariguera (1) mariposa. INAH (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia) notes that “These nose rings were given by the rulers to those warriors who distinguished themselves by their bravery and courage on the battlefield. This ornament, achieved through the techniques of lamination and embossing, represents the wings of the insect in a very stylized way.”

- nariguera = “nose ring” (more or less) – a gold ornament that was hooked to the nostrils and might be in the shape of a simple ring, a laminated disk, or an upside-down fan decorated with pierced work. (mariposa = butterfly)

Karen can be found at….

- Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/karen.vargascorrea/

- Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/karenvargascorrea/?hl=en

By the stone carvers hand

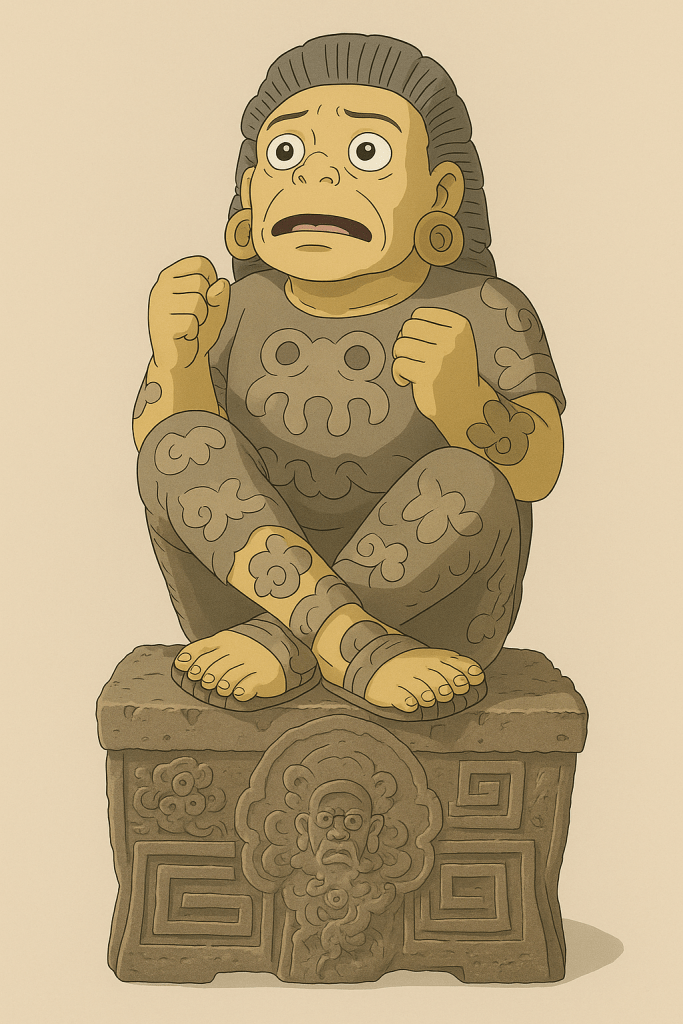

The Tlamanalco statue is without doubt the most well known (and well crafted) effigy of Xochipilli.

It was discovered in the middle of the 19th century in the region of Chalco, near Tlalmanalco, on the slopes of Popocatépetl and is currently in the Mexica room of the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

Little is known and much is presumed of this statue. The first analysis of the statue of Tlalmanalco is a note published in 1882 in the Annals of the Museum of Mexico, as part of the first classification of the pieces of the museum (Pomedio 2005). The statue, according to Alfredo Chavero (1958), represents Ixcozauhtli, god of the sun.

Another analysis of the effigy was published by Peñafiel in 1910, who interprets the tonallo and tlapapalli motifs on the statue according to the Féjervary-Mayer codex and the cult of Tonatiuh. A description from 1937 made by Caso and Mateos Higuera is found in the catalogue of the collection of monoliths of the Museum of Anthropology of Mexico. The first true iconographic study was published in 1959 by Justino Fernandez, who sees in Xochipilli a god of flowers, but also of the rising sun. Schultes and Hofmann published an analysis in 1979, but it focused only on identifying the flowers that covered the statue (and information is now coming forward that suggests many of these plants were misidentified and perhaps that the images – or several of them – depict a single plant at different stages of its lifecycle)

Plundered treasures

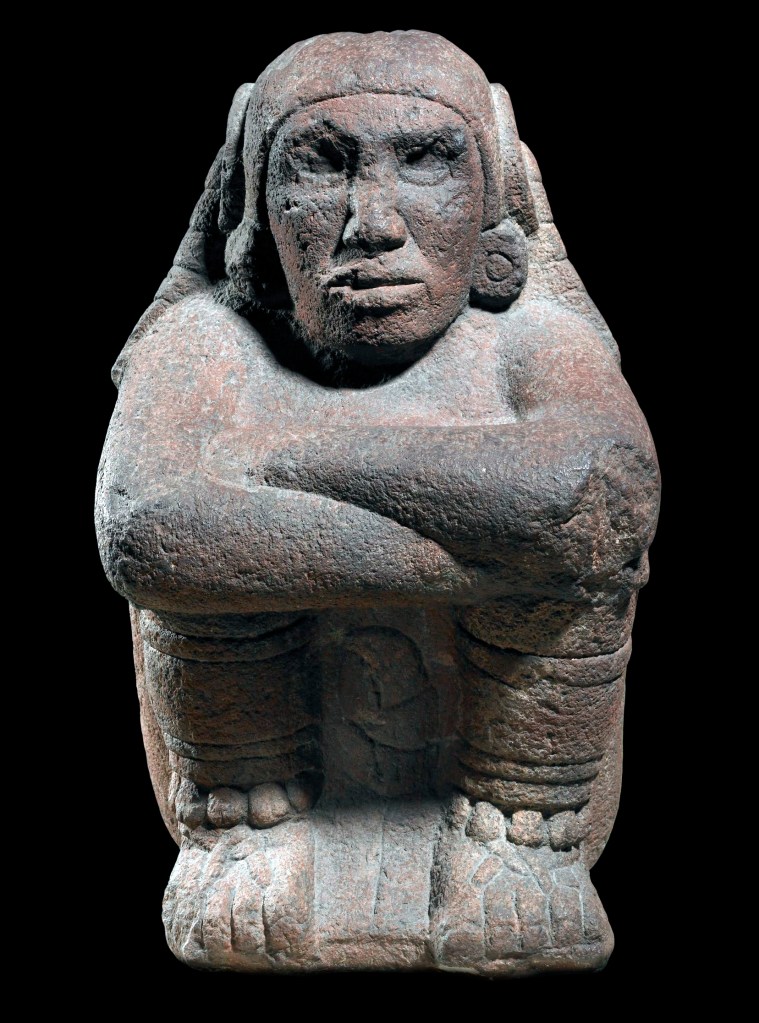

William Bullock (c. 1773 – 7 March 1849) was an English traveller, naturalist (1) and antiquarian (2). Bullock began as a goldsmith and jeweller in Birmingham. By 1795 Bullock was in Liverpool, where he established a Museum of Natural Curiosities (called Bullock’s Museum) at 24 Lord Street in Lverpool which he then moved to London in 1809. In 1812 Bullock commissioned the construction of the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly as a museum to house his collection, which included “curiosities” brought back from the South Seas by Captain Cook (3). In 1822 Bullock went to Mexico where he became involved in silver mine speculation. He brought back many artefacts and specimens which formed a new exhibition in the Piccadilly Egyptian Hall. In 1822 the statue shown above became part of Bullock’s private art collection. In 1825 it was donated to the British Museum in London by Bullock (where it still currently resides). The exact year in which this statue was found is unknown, but researchers believe that it may have been found during excavations in the ancient capital of the Aztec or Mexica Empire, in the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan.

- Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is called a naturalist or natural historian.

- An antiquarian or antiquary (from Latin antiquarius ‘pertaining to ancient times’) is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient artefacts, archaeological and historic sites, or historic archives and manuscripts.

- Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer who led three important voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans between 1768 and 1779. He completed the first recorded circumnavigation of the main islands of New Zealand, and was the first European to visit the east coast of Australia and the Hawaiian Islands. Captain Cook is renowned for his success in combating the scourge of scurvy, a debilitating disease of nutritional deficiency (specifically Vitamin C) that plagued sailors during long sea voyages and is estimated to have killed over two million sailors between the 16th and 18th centuries. Cook implemented various strategies, including dietary changes and strict hygiene practices, which significantly reduced the incidence of scurvy among his crew and allowed him to keep his crew healthy during long voyages which enabled him to explore vast stretches of the Pacific Ocean

Figure of the god Xochipilli-Macuilxochitl : Mexico, Aztec, 1450-1520 AD.

Carved from volcanic stone

Height: 74.5 cm; Width: 31cm; Diameter: 26cm

I have seen it noted that this version of Xochipilli is attired as a cuāuhocēlōtl or Eagle Warrior as he is wearing an eagle mask typical to this elite class of Soldier.

This statue is currently housed at the Reiss Engelhorn Museum, or Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen, in Mannheim, Germany

Xochipilli in the guise of Macuilcoatl (Five serpent macuil – five : coatl – serpent), one of the Ahuiateteo or Macuiltonaleque, or “lords of the five souls” (macuil, “five” + tonalli, “soul”) which embodied the dangers and consequences of overindulgence, including excessive drinking, gambling, and sex.

Now this will require further research on my behalf as previously I was aware of there being only five Macuiltonaleque, these being…..

- 5 Lizard (Macuilcuetzpalin)

- 5 Vulture (Macuilcozcacuahtli)

- 5 Rabbit (Macuiltochtli) – this ahuiateteo is also part of the Centzon Tōtōchtin, the four hundred rabbits which were all gods of drunkenness. See Mayahuel and the Cenzton Totochtin. for further details

- 5 Grass (Macuilmalinalli)

- and, of course, Macuilxochitl – 5 Flower – Xochipilli himself

The number 5 in this case references the “fifth cup” which symbolised overindulgence and the descent into inebriation. Drunkenness was frowned upon in Aztec society (particularly by the Mexica). Public drunkenness was punished by a beating and repeat infractions (except by the elderly who were generally exempt from the rule) could even result in death. The fifth cup involved the drinking of octli (or pulque), four cups was considered allowable but the fifth cup was the one that intoxicated. This goes back to the legend of Quetzalcoatl who was tricked into drinking a fifth cup of pulque which resulted in his drunkenness and having sexual relations with his sister; the shame of which resulted in him abandoning his people.

Anales de Cuauhtitlan – Codex Chimalpopoca

40) They came to Xonacapacoyan (where onions are washed) to stay with their farmer, Maxtlaton, who was the guard of Toltecatépec. They cooked quelites (edible herbs), tomatoes, chile, corn and green beans. This was done in a few days. There were also magueys there, which they asked Maxtla for; and in only four days they made pulque and collected it; they discovered some jars of honey to pour the pulque into. They then went to Tollan, to Tzalcoatl, carrying everything, his quelites, his chiles, etc., and the pulque. They arrived and rehearsed. Those who guarded Quetzalcoatl did not allow them to enter; two and three times they turned them back, without being received. Finally, when asked where they were from, they answered and said that they were from Tlamacazcatépec and Toltecatépec. So Quetzalcoatl heard this and said, “Let them come in.” They came in, saluted, and finally gave him the quelites, etc. After he had eaten, they begged him again and gave him the pulque. But he told them, “I will not drink it, because I am fasting. Perhaps it is intoxicating or killing.” They said to him, “Try it with your little finger, because he is angry, it is strong wine.” Quetzalcoatl tasted it with his finger; he liked it and said, “I am going, grandfather, to drink three more portions.” For the devils told him, “You must drink four.” So they gave him the fifth, saying, “It is your libation.” After he drank, they gave all his pages five cups each, which they drank and got completely drunk.

41) Again the demons said to Quetzalcoatl: “My son, sing. Here is the song that you must sing.” And Ihuimécatl sang: “My house of quetzalli feathers, my house of zaquan feathers, my house of corals, I will leave it. An-ya.”

42) When Quetzalcoatl was now happy, he said: “Go and bring my older sister Quetzalpétlatl; let us both get drunk.” His pages went to Nono hualcatépec, where she was doing penance, to tell her: “Lady, my daughter, Quetzalpétlatl, fasting woman, we have come to take you. The priest Quetzalcoatl awaits you. You are to be with him.” She said: “It is a good time. Let us go, grandfather and page.” And when he came to sit beside Quetzalcoatl, they gave him four rations of pulque and one more, his libation, the fifth. Ihuimécatl and Toltécatl, the drunkards, to also give music to Quetzalcoatl’s eldest sister, sang:

43) “Oh you, Quetzalpétlatl, my sister, where did you go on the day of the harvest? Let us get drunk. Ayn! ya! ynya! ynye! an!”

44) After they got drunk, they no longer said: “But we are hermits!” They no longer went down to the irrigation ditch; they no longer went to put thorns on themselves; they no longer did anything at dawn. When dawn broke, they became very sad, their hearts softened. Then Quetzalcoatl said: “Woe is me!” And he sang the plaintive song that he composed to leave there:

From the sculptors hand

Artisanry of the Goldsmith

Tomb 7 at Monte Alban is one of the richest burial contexts ever encountered from pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. It was discovered by the Mexican archaeologist Alfonso Caso in 1931, and it quickly became famous through popular publications such as National Geographic. In 1969 Caso published the definitive work on the tomb in his “El Tesoro de Monte Alban”, which catalogued the hundreds of exotic objects of precious materials

Xochipilli pectorals (nos. 146a, b and c; 34N and 167b). They are practically identical and seem to have been cast in the same mould. Only those marked with the number 146 appeared together. All these pectorals feature a human figure wearing an eagle or pheasant’s head as a helmet and a nose ring in the shape of a stylised butterfly, which the Mexicans called yacapapalotl . On the lower part, instead of the two square plaques of the pectoral of the dates, we see a long rectangular plaque, but without any decoration. Alfonso believed that these figures were representations of the god Xochipilli-Macuilxochitl “The Lord of the Flowers” or “5 Flower”, god of games, love, song and dance, god of summer, and one of the multiple aspects of the solar god. The bird covering his head may be an eagle or a pheasant (Coxcoxtli), since both disguises represent this deity and that is why we can consider him the patron of the eagle knights.

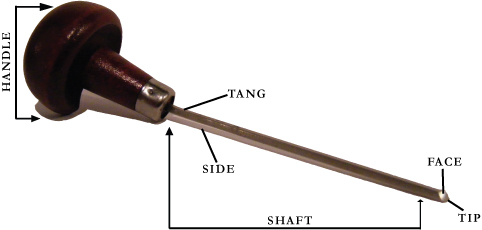

Tools of a goldsmith

The burin of a goldsmith of Moctezuma (López Luján etal 2016)

The goldsmith tradition of ancient Azcapotzalco left material vestiges. Especially significant in this sense are the archaeological finds made in the Refinería-Azcapotzalco axis between E and Tepantongo streets, next to the Azcapotzalco Metro station, in the San Marcos Ixquitlan neighborhood of old Tepanecapan.

Between the end of 1980 and mid-1982, a group of specialists from the then Subdirectorate of Archaeological Salvage of the INAH explored a Late Postclassic occupation there (1325-1521 AD), and recorded a total of 326 human burials.

As expected, many of the individuals exhumed in said area had metallic objects among their funerary offerings, highlighting the character of the so-called burial 240.

A very special funeral offering

According to field reports, the individual from burial 240 had the richest offering in the excavation area. Among other objects, copper and bronze instruments were offered to him, such as a chisel (with 2.64% arsenic and 0.44% tin) for cutting, striking and embossing; a needle (with 3.9% arsenic and 1% tin), perhaps for glazing or for piercing, outlining and marking; a burin (with 5.5% arsenic and 1.26% tin) to create straight grooves on the sheet by pressure or outline designs that will later be embossed, and a pear-shaped bell (with 32.6% lead, a high concentration typical of the pieces of the Cuenca of Mexico, which facilitated decoration with false filigree).

The just mentioned burin is, without a doubt, the most interesting object of the set. It was found next to the skull of the individual and facing east. It was identified at the time of the excavation as an eagle knight carved in bone that served as the end of a command staff or the handle of a knife. Its functional end is a bronze tip fitted with a straight mouth with a double bevel. The handle is ergonomic, allowing a comfortable grip with the thumb, index finger and middle finger. This one was actually carved from the centre branch of a whitetail deer right antler. It represents the god.

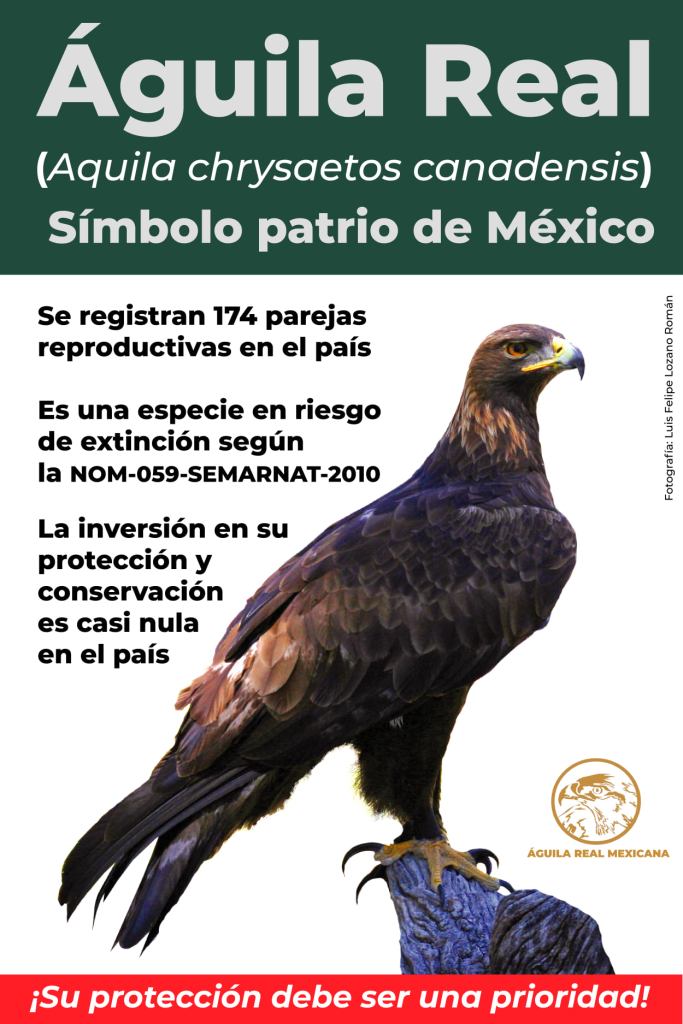

Commonly, Xochipilli appears in iconography dressed or represented as a royal eagle, hocofaisán or cojolite (águila real, hocofaisán o cojolite). This important divinity is not only the patron saint of music, dance, singing, games and sexual pleasure, but also represents the rising Sun itself and is directly linked to gold and metalwork, which is confirmed in the numerous jewels with his effigy from tomb 7 of Monte Albán (as noted in the section under mascaras/masks).

Great Curassow (Crax rubra)

See Xochipilli : Hymn to Xochipilli for more information on these birds (and how they relate to the headdress of Xochipilli).

A burin is a steel cutting tool used in engraving, from the French burin. Its older English name and synonym is graver. This sense is not to be confused with the prehistoric stone tools

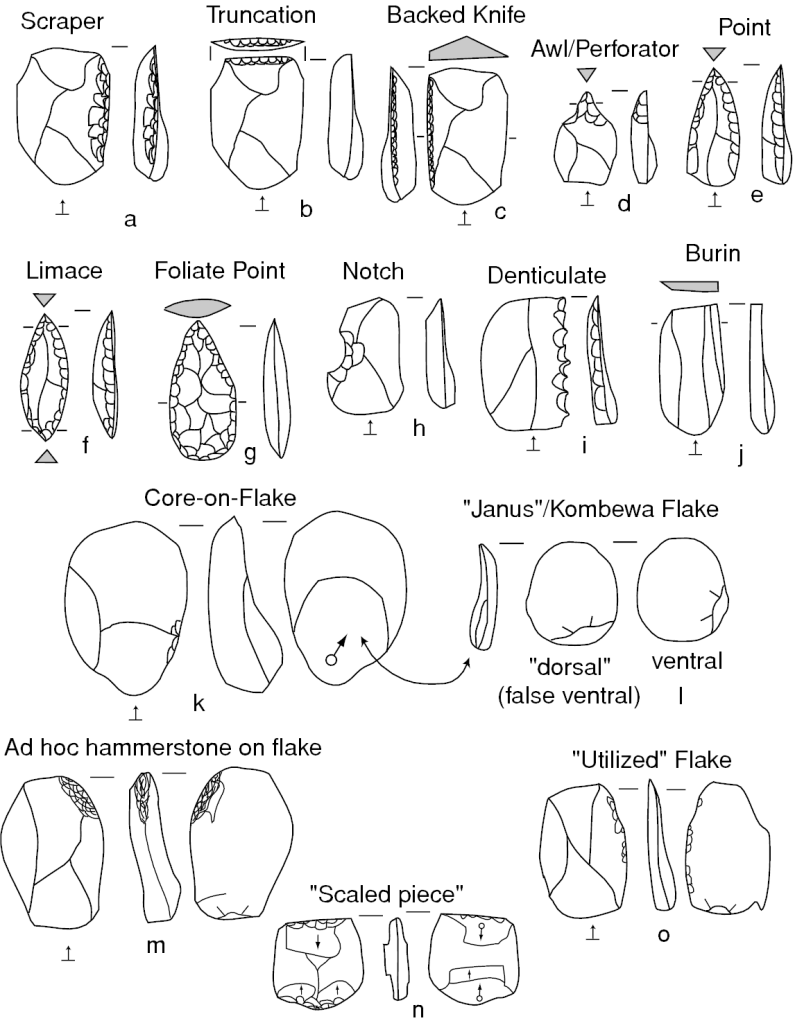

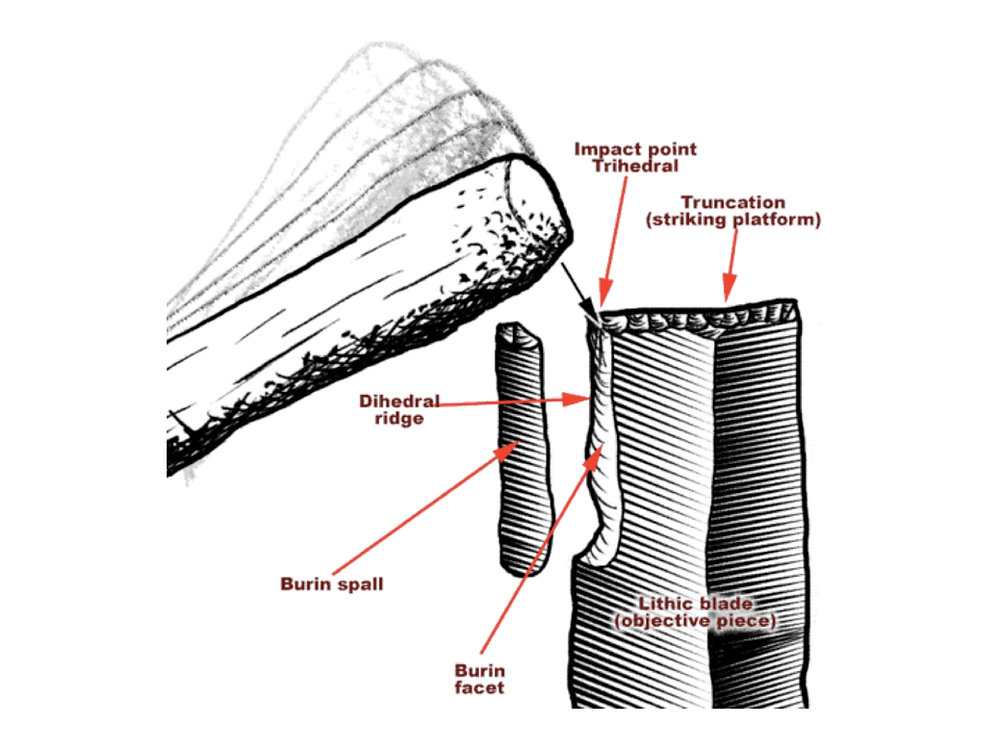

In archaeology and the field of lithic reduction, a burin /ˈbjuːrɪn/ (from the French burin, meaning “cold chisel” or modern engraving burin) is a type of stone tool, a handheld lithic flake with a chisel-like edge which prehistoric humans used for carving or finishing wood or bone tools or weapons, and sometimes for engraving images.

In archaeology, burin use is often associated with “burin spalls”, which are a form of debitage created when toolmakers strike a small flake obliquely from the edge of the burin flake in order to form the graving edge.

Macuilxóchitl-Xochipilli was linked with joy, music, song, the dawn, the child sun, and his role was to attend to the nobles who participated in banquets, dances, and hunts where honors were paid to him.

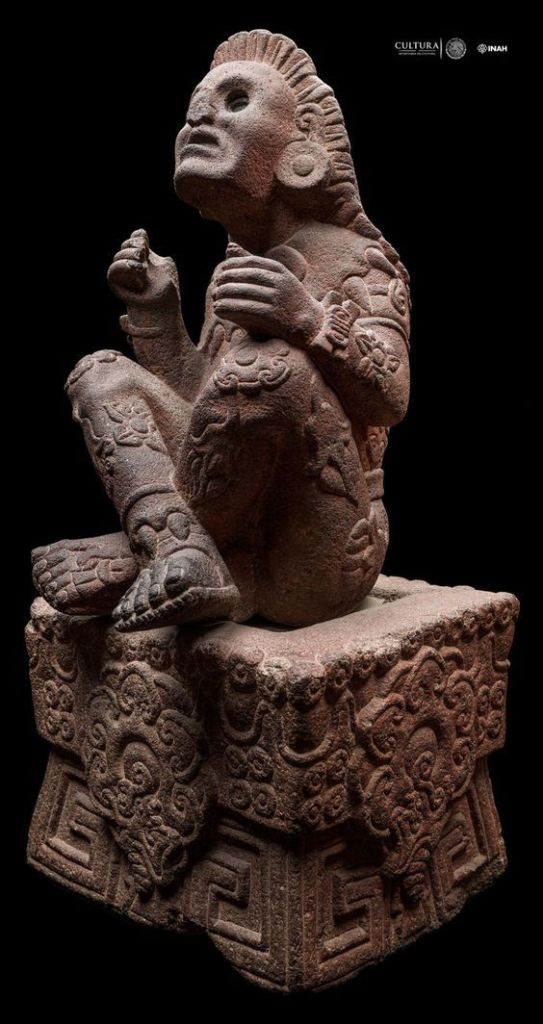

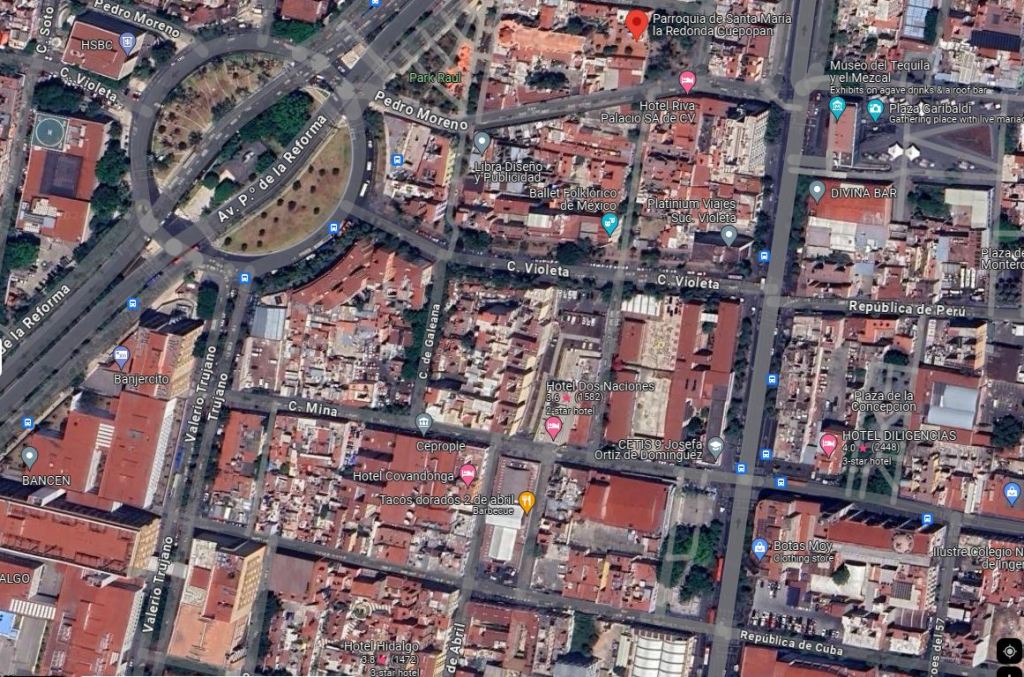

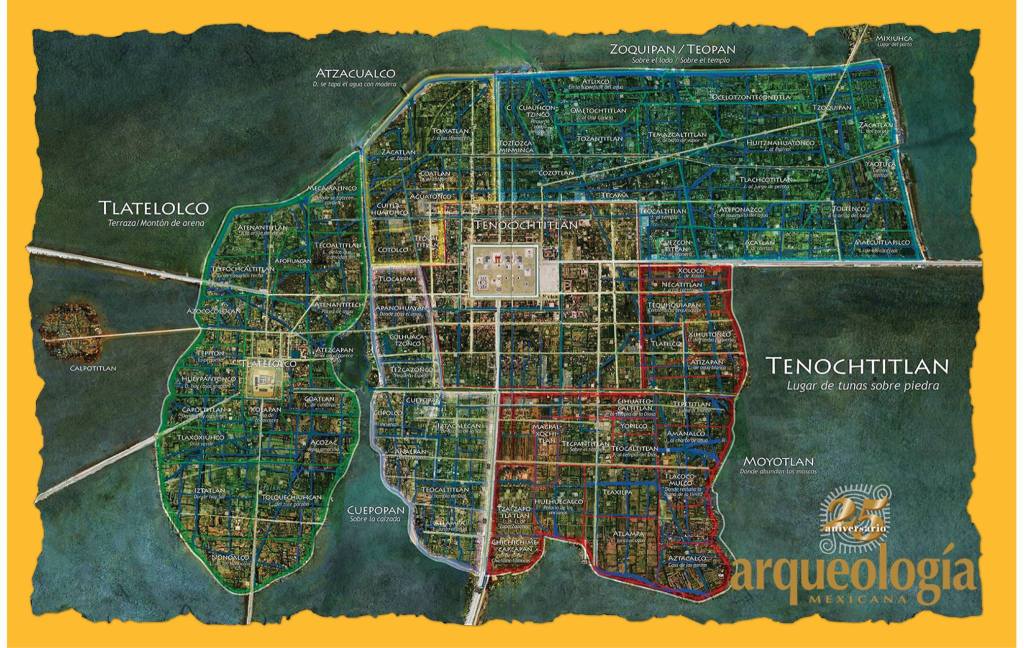

The piece was found in July 2019 during the rehabilitation work of the Santa María la Redonda parish in the neighborhood of Santa María Cuepopan, right at the intersection of Violeta and Galeana streets in the Guerrero neighborhood.

Violeta Street was part of the Cuepopan-Tlaquechiuhca neighborhood, one of the four neighbourhoods of Tenochtitlan.

Diego Prieto, head of the INAH, explained that it is a sculpture from the last stage of Tenochtitlán that was alone at the burial, from which it is deduced that it was placed there by accident or was carried by the river current.

“Probably one of the four that formed part of Tenochtitlán was part of the main altar in the centre of the Cuepopan neighbourhood, which was later called Santa María Cuepopan, later renamed Santa María La Redonda,” said Prieto, recalling that Violeta Street was a road that connected the east and west sides of the city, so the discovery of ancient pieces is not strange.

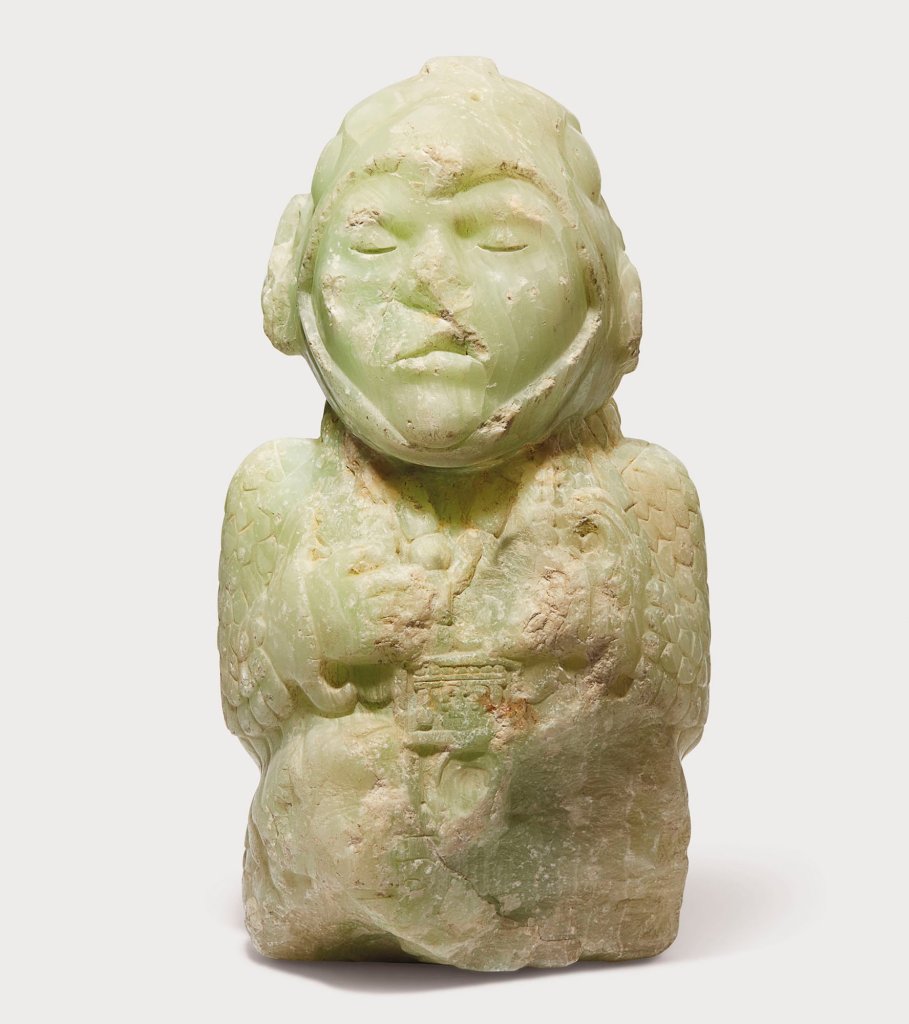

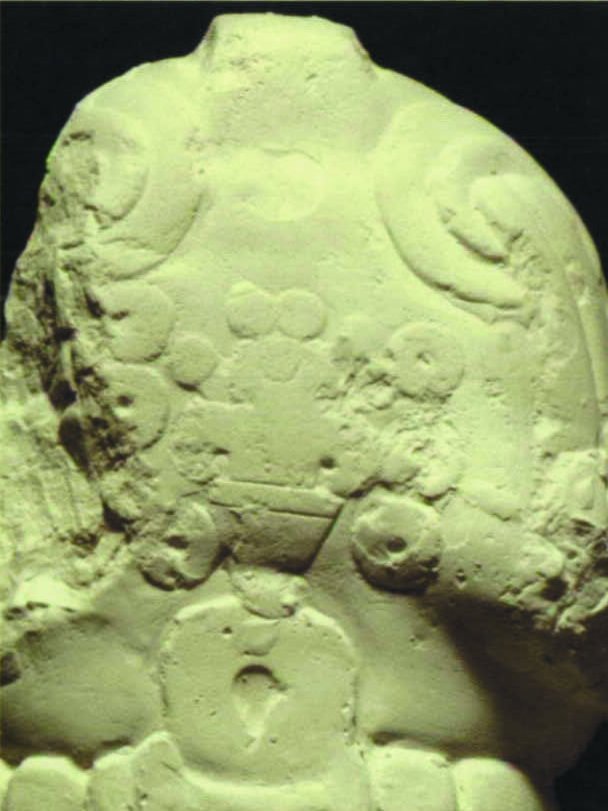

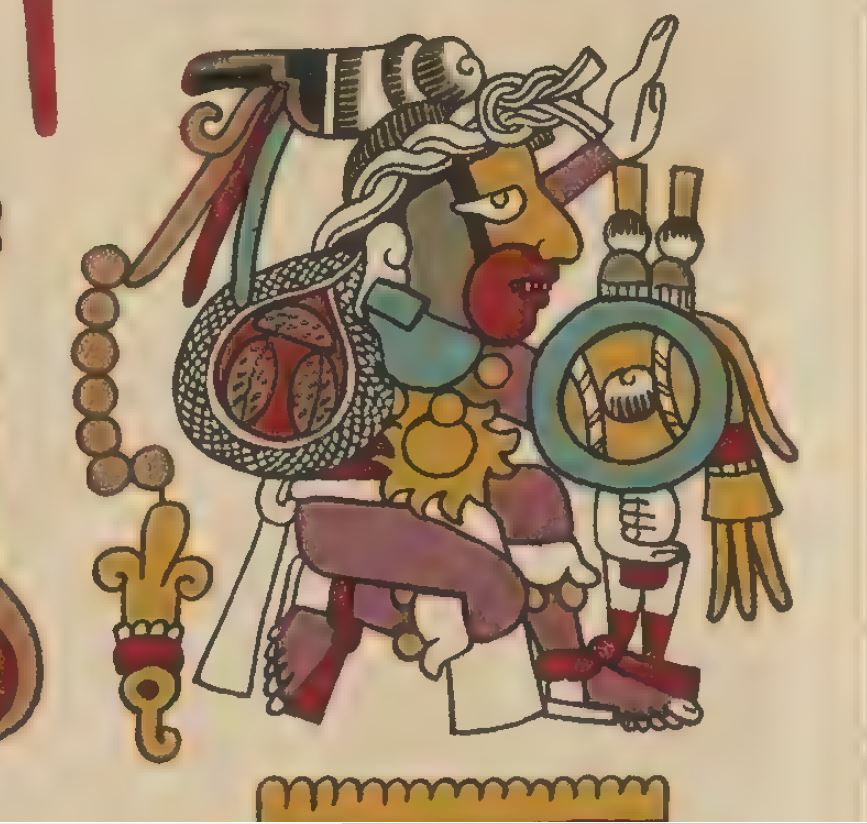

Despite being three meters underground, the sculpture only has a broken nose. The researchers determined, from the Bourbon codices and the First Memorials, that the piece refers to the gods Xochipilli and Macuilxóchitl, as it shows attributes of both.

The first wears the headdress, the necklace with chalchihuites and the chimalli, and the second protrudes the mouth that shows seven teeth and simulates a flower, but represents the palm of a hand.

The character wears a maxtlatl or loincloth, carries jewels typical of the nobility such as wavy lines around the mouth, earmuffs, a necklace, and a shield with his arrow or dart.

The most characteristic feature identifying the statue as Macuilxóchitl is the mouth paint that represents the palm of a hand.

The sculpture is made of marbled marble, a metamorphic rock with veins of serpentine and has traces of manufacturing typical of the Mexica tradition; it is estimated to have been made between 1469 and 1481.

Obsidiana

Obsidian Head from a figure, Xochipilli-Macuilxochitl Aztec15th–early 16th century

Aztec Diety Image of Xochipilli-Macuilxochitl, Late Postclassic, ca. A.D. 1450-1521. Light-green aragonite (Mexican onyx marble-tecali), height 12in (30.5cm); width 5 3/4in (19cm)

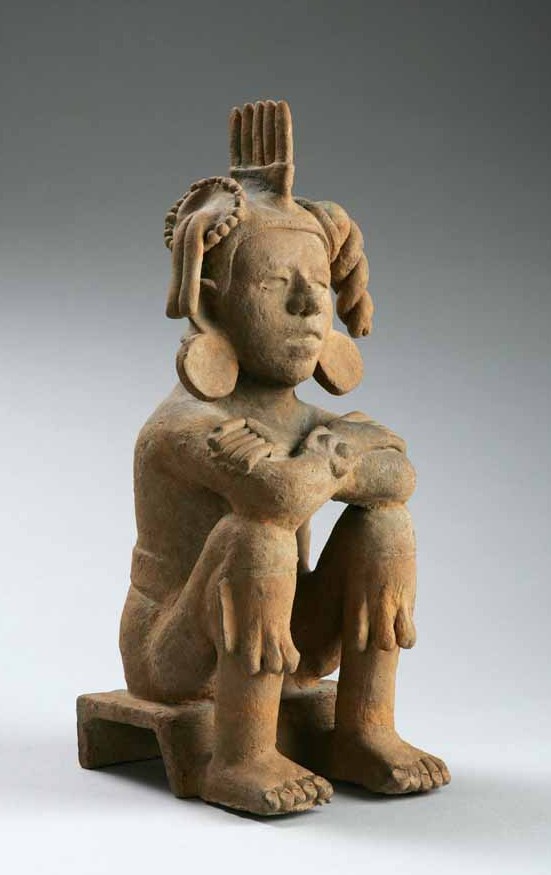

Works in terracotta.

Xantil (plural xantiles) : ceramic braziers that functioned as receptacles for a type of incense known as copal

From the artists quill

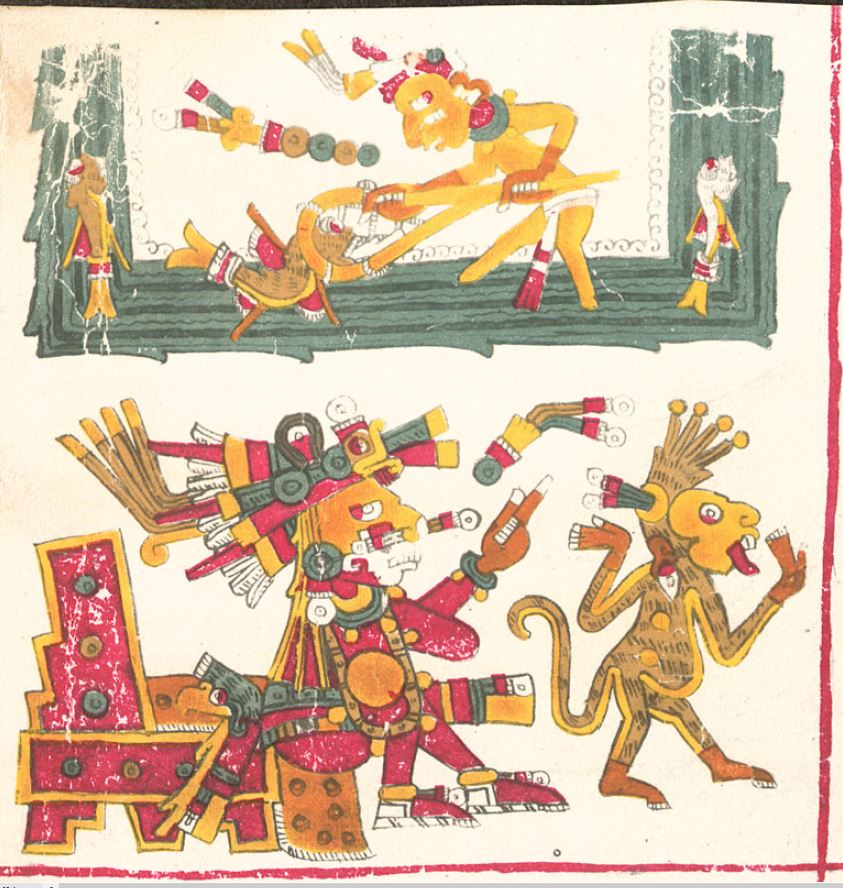

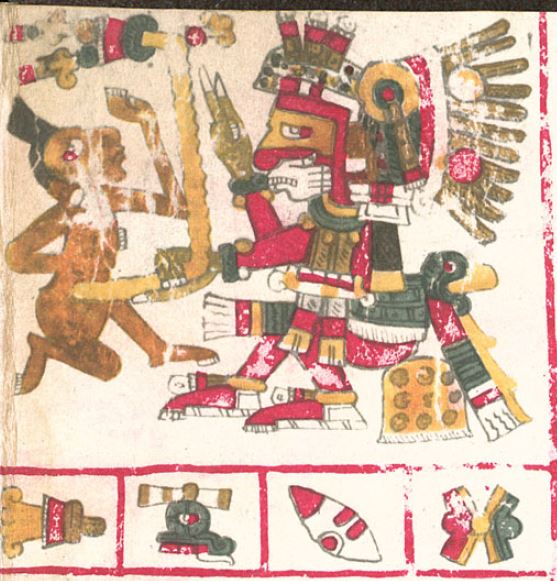

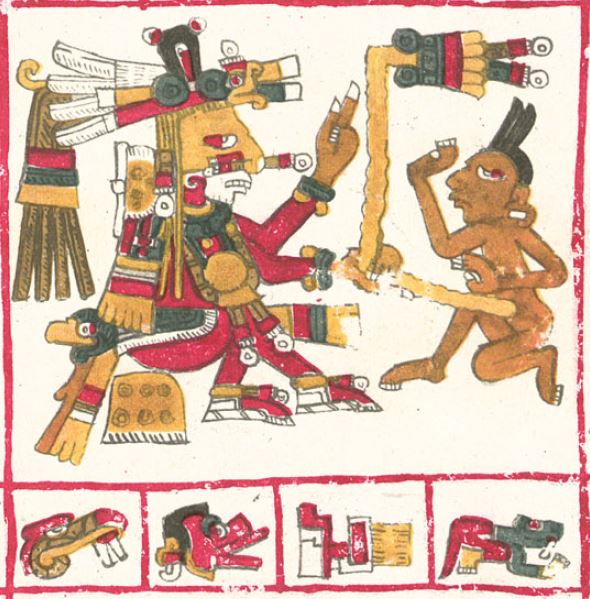

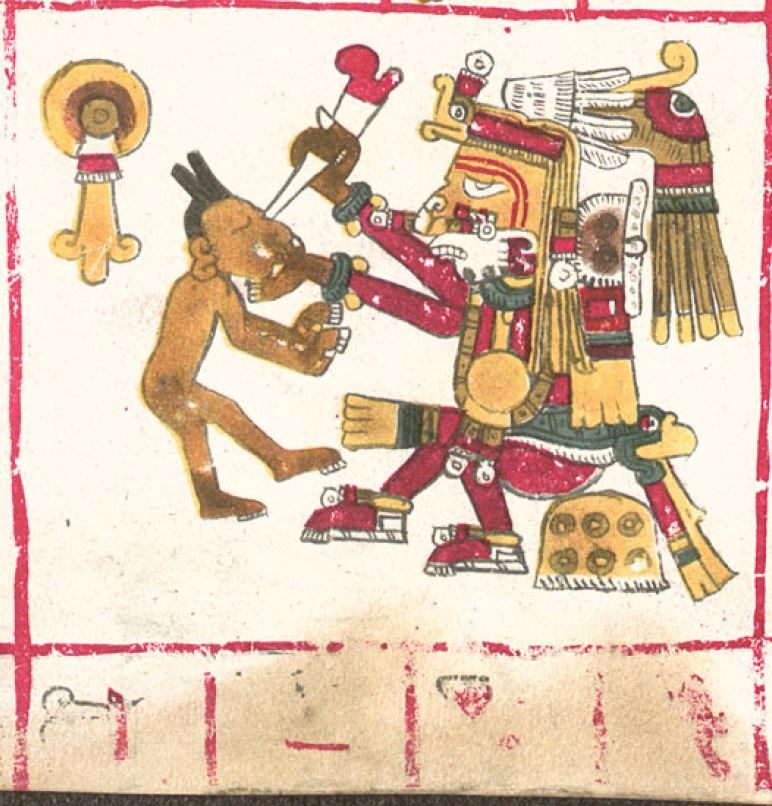

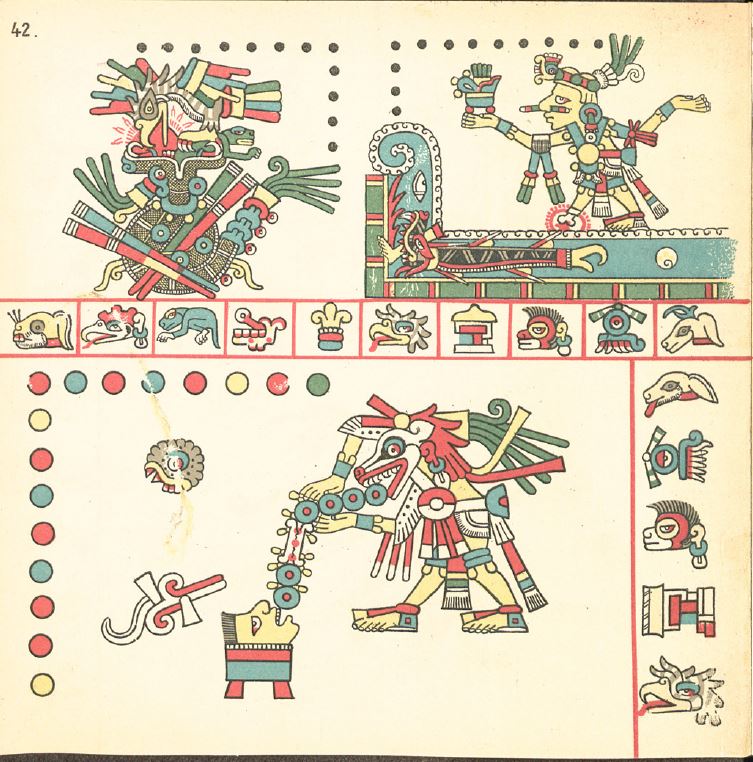

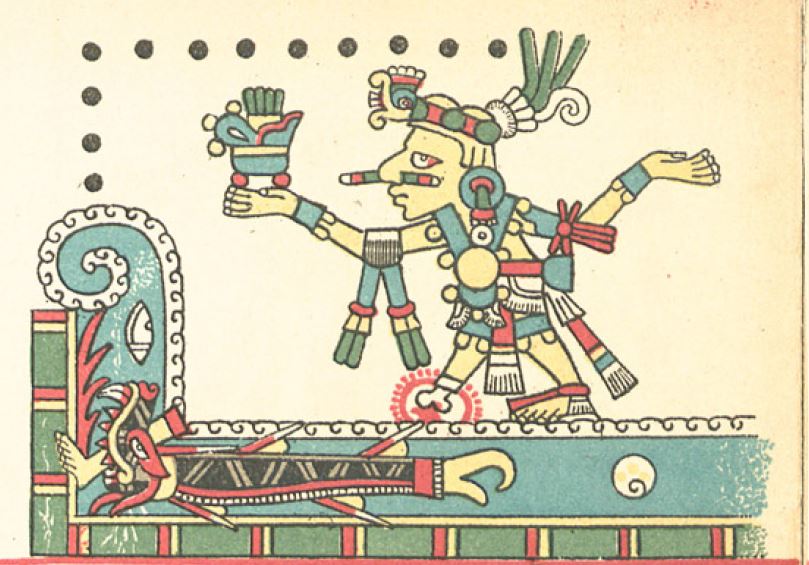

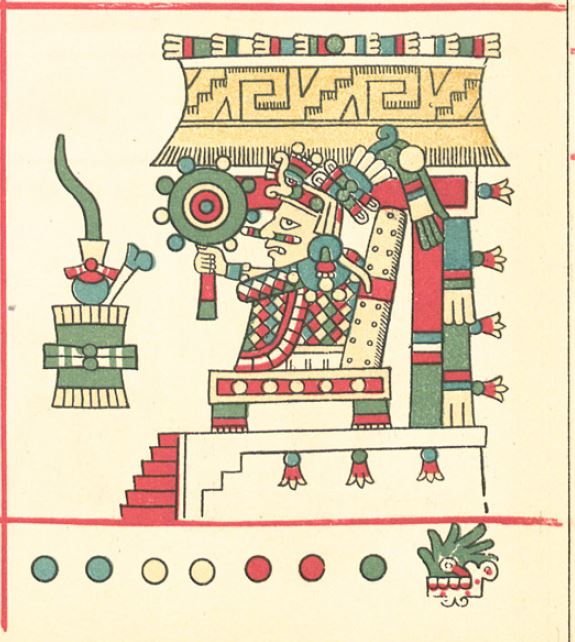

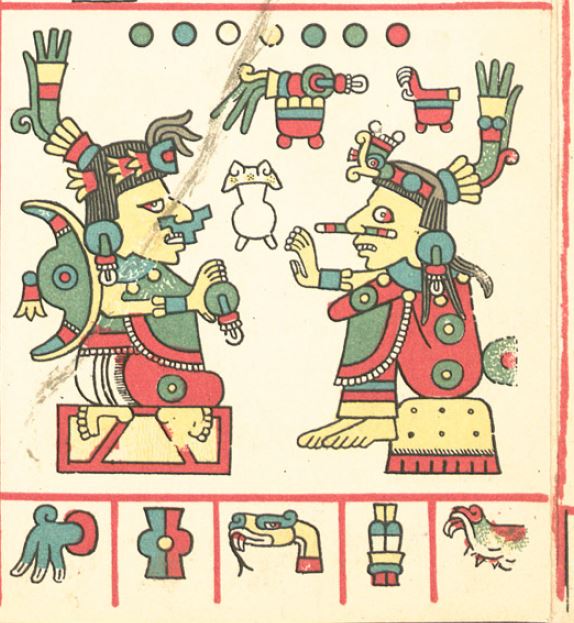

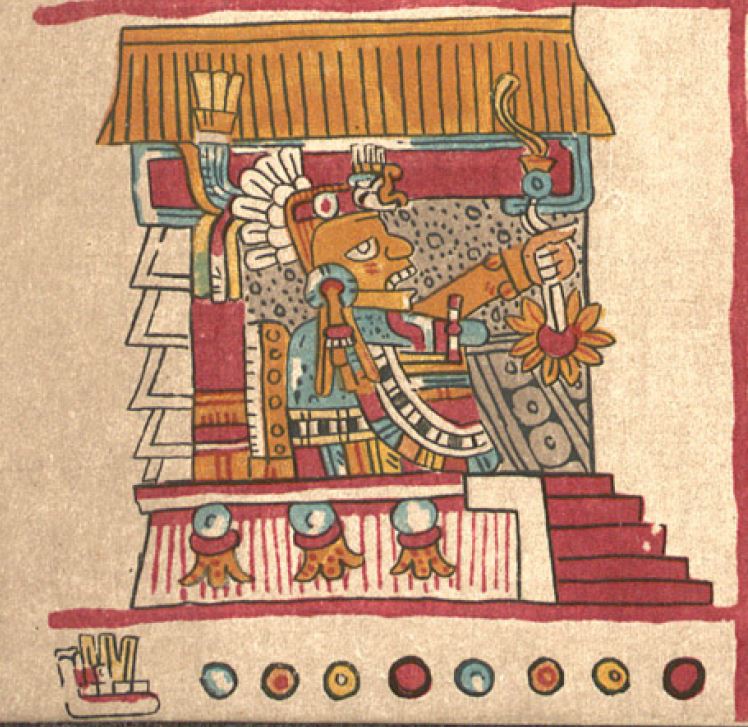

Codex Borgia

The Codex Borgia, also known as Codex Borgianus, Manuscrit de Veletri and Codex Yohualli Ehecatl, is a pre-Columbian Middle American pictorial manuscript from Central Mexico featuring calendrical and ritual content, dating from the 16th century. It is named after the 18th century Italian cardinal, Stefano Borgia, who owned it before it was acquired by the Vatican Library after the cardinal’s death in 1804

The codex is made of animal skins folded into 39 sheets. Each sheet is a square 27 by 27 cm (11 by 11 in), for a total length of nearly 11 metres (36 ft). All but the end sheets are painted on both sides, providing 76 pages. The codex is read from right to left.

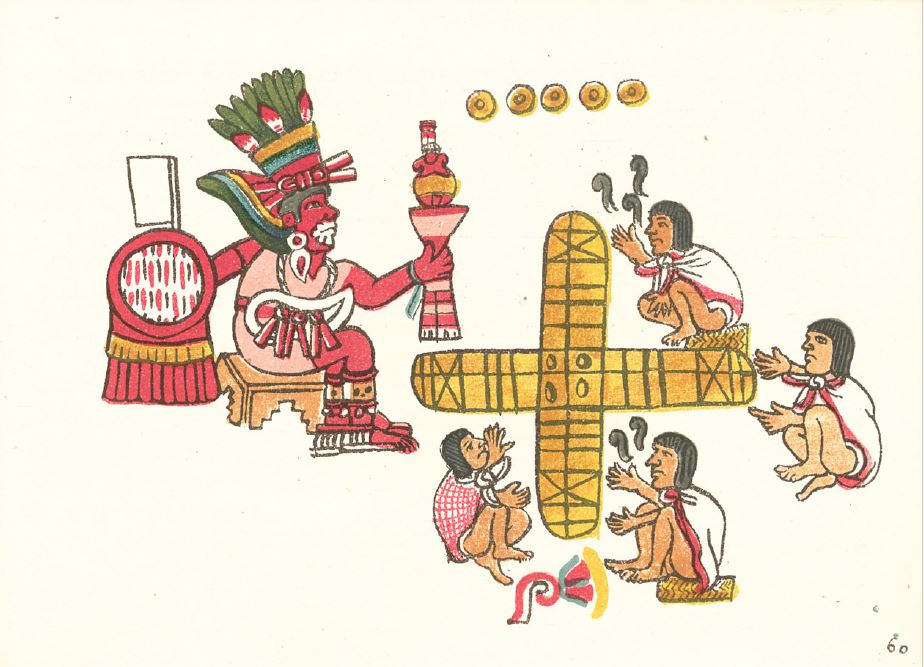

Codex Fejérváry-Mayer

The Codex Fejérváry-Mayer is an Aztec Codex of central Mexico. It is a divinatory almanac in 17 sections. As a typical calendar codex tonalamatl dealing with the sacred Aztec calendar – the tonalpohualli – it is placed in the Borgia Group. It is named after Gabriel Fejérváry (1780–1851), a Hungarian collector, and Joseph Mayer (1803–1886), an English antiquarian who bought the codex from Fejérváry.

This codex is made on deerskin parchment folded accordion-style into 23 pages. It measures 16.2 centimetres by 17.2 centimetres and is 3.85 metres long.

The Borgia Group is the scholarly designation of a number of mostly pre-Columbian documents from central Mexico. In 1830–1831, they were first published in their entirety as colored lithographs of copies made by an Italian artist, Agustino Aglio, in volumes 2 and 3 of Lord Kingsborough’s monumental work titled Antiquities of Mexico. They were named the “Codex Borgia Group” by Eduard Seler, who in 1887 began publishing a series of important elucidations of their contents

Codex Laudianus

The Codex Laud, or Laudianus, is a sixteenth-century Mesoamerican codex named for William Laud, an English archbishop who was the former owner. It is from the Borgia Group, and is a pictorial manuscript consisting of 24 leaves (48 pages) from Central Mexico, dating from before the Spanish takeover. It is evidently incomplete (part of it is lost). It is a handbook and almanac for time-based prognostication and related rituals, with most of the content presented from right to left and is closely related to the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, often referred to as its stylistic twin; indeed, the two manuscripts may be the work of the same workshop or painter-scribe. It is part of the Borgia group of codices.

Codex Vaticanus B

Codex Vaticanus B, also known as Codex Vaticanus 3773, Codice Vaticano Rituale, and Códice Fábrega, is a pre-Columbian Middle American pictorial manuscript, probably from the Puebla part of the Mixtec region, with a ritual and calendrical content. It is a member of the Borgia Group of manuscripts

Codex Vaticanus B is a screenfold book made from ten segments of deerskin joined together, measuring 7240 centimeters in total length. These segments have been folded in 49 pages in an accordion fashion, each page measuring 14.5 by 12.5 centimeters, making it one of the smallest Mesoamerican codexes

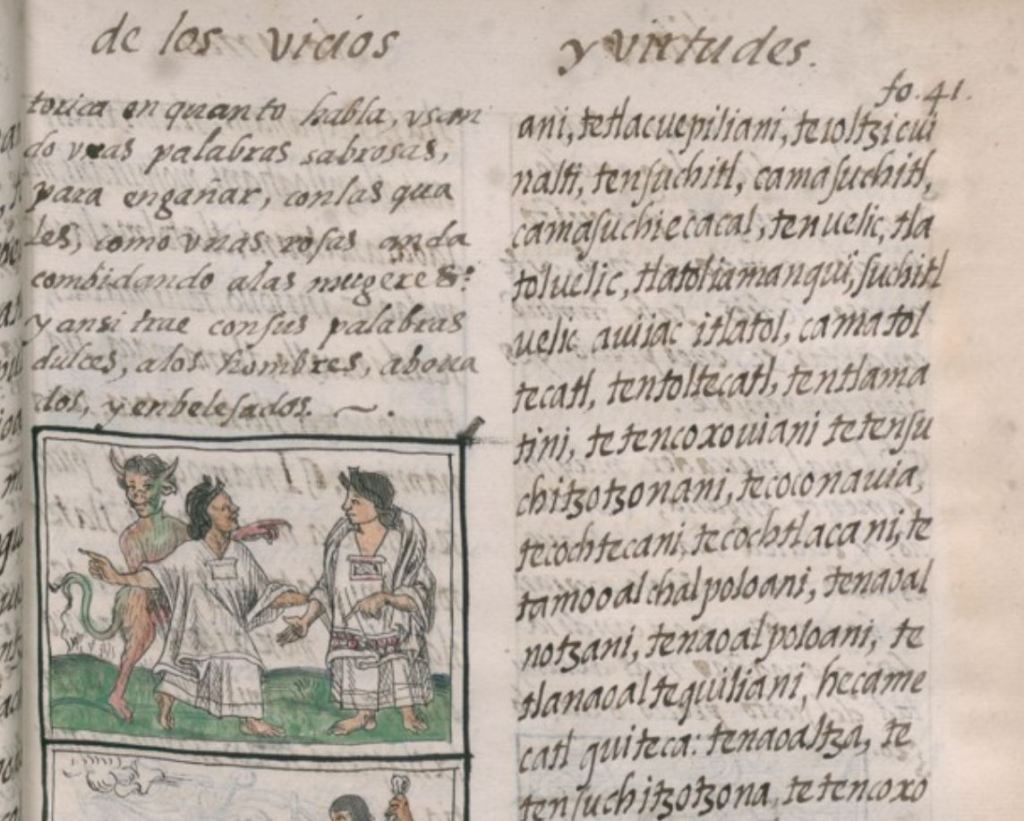

Codex Magliabechiano

The Codex Magliabechiano is a pictorial Aztec codex created during the mid-16th century, in the early Spanish colonial period. It is representative of a set of codices known collectively as the Magliabechiano Group (others in the group include the Codex Tudela and the Codex Ixtlilxochitl). The Codex Magliabechiano is based on an earlier unknown codex, which is assumed to have been the prototype for the Magliabechiano Group. It is named after Antonio Magliabechi, a 17th-century Italian manuscript collector

This codex created on European paper, with drawings and Spanish language text on both sides of each page. The Codex Magliabechiano is primarily a religious document. Various deities, indigenous religious rites, costumes, and cosmological beliefs are depicted. Its 92 pages are almost a glossary of cosmological and religious elements. The 52-year cycle is depicted, as well as the 20 day-names of the tonalpohualli, and the 18 monthly feasts.

Codex Nuttall

The Codex Zouche-Nuttall or Codex Tonindeye is an accordion-folded pre-Columbian document of Mixtec pictography. It is one of about 16 manuscripts from Mexico that are entirely pre-Columbian in origin.

The Codex Zouche-Nuttall was probably made in the 14th century and is composed of 47 sections of animal skin with dimensions of 19 cm by 23.5 cm. The codex folds together like a screen and is vividly painted on both sides. It is one of three codices that record the genealogies, alliances and conquests of several 11th and 12th century rulers of a small Mixtec city-state in highland Oaxaca, the Tilantongo kingdom, especially under the leadership of the warrior Lord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw.

Modern artistic representations

Calendar art

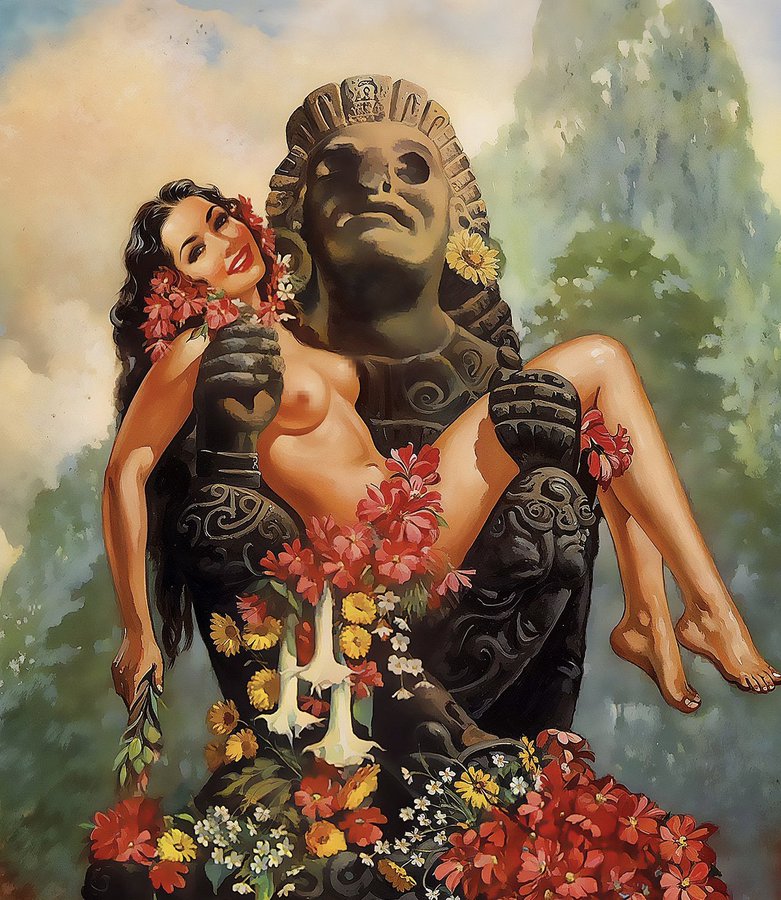

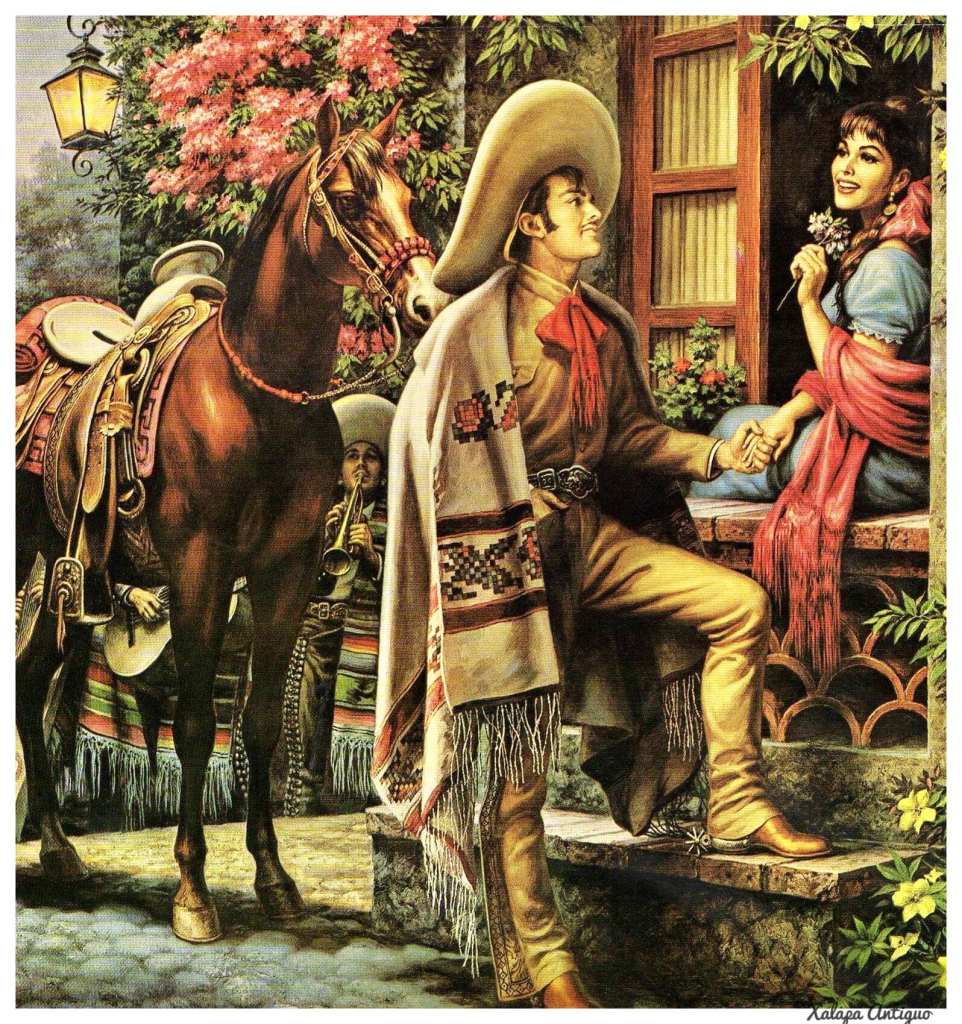

Galas de México (S.A. de C.V.) has the distinction of being the most recognized factory producing calendars and stickers for advertising in Mexico for almost 100 years. The company bears the name of its founder Don Santiago Galas Arce (1886-1970). In 1930 Galas started its own Offset process to print chromes and advertising calendars and in 1933 they set up a studio in their facilities for the most recognized painters of the day to make original paintings in order to produce their calendars. This was Mexico’s golden age of calendar girls and Galas de Mexico printed images from artists such as: Jesús de la Helguera, Jorge González Camarena, Josep Renau, Eduardo Cataño, José Bribiesca, Armando Drechsler, Jaime Sadurní, and dozens of other painters. The calendars flourished until 1970, “the year of Santiago Galas’ death.

One of my favourite artists from this era was Luis Amendolla

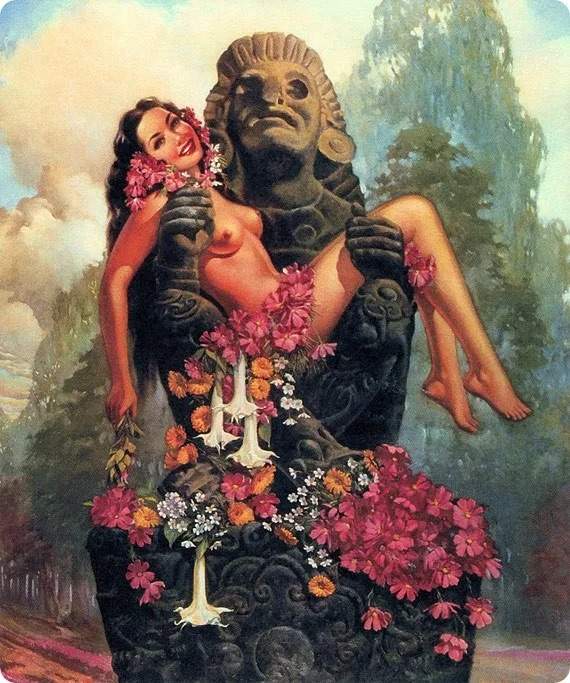

Litografía de Luis Amendolla de 1940, donde aparece una mujer siendo sujetada por la famosa escultura del “Señor Florido o de las Flores”, Xochipilli.

The image above was posted on Twitter (X) but it is a rejigged copy of the original.

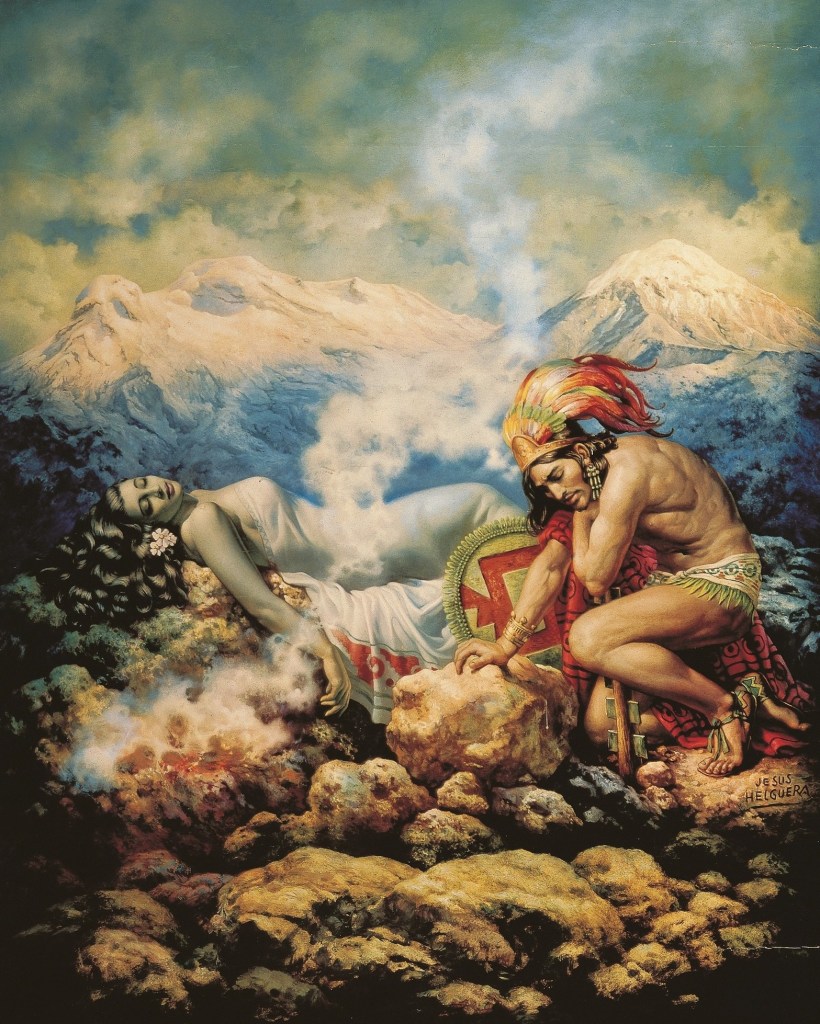

Jesús Helguera

Jesús Enrique Emilio de la Helguera Espinoza, was born on May 28th 1910 to Alvaro Garcia Helguera and Maria Espinoza Escarzarga in Chihuahua, Mexico. He lived his childhood in Mexico City and later moved to Córdoba in the state of Veracruz. His family fled from the Mexican Revolution to Ciudad Real, Castilla la Nueva, Spain in 1917 and thereafter moved to Madrid. In 1938 He was forced to move back to the Mexican state of Veracruz with his family, his wife Julia Gonzáles Llanos and his two children (María Luisa and Fernando), due to economic pressures caused by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936.

Jesús first gained interest in the arts during primary school and would often be found wandering the halls of the Museo Nacional del Prado (Del Prado Museum) in Madrid. At 12 years old, he attended the Escuela de Artes y Oficios then, at the age of 14, he was admitted to the Escuela Superior de Bellas Artes and later studied at the Academia de San Fernando. He became a professor of visual arts at a Bilbao Art Institute at the age of 18.

He was hired as an illustrator at the Barcelona publishing house Editorial Araluce working on books, magazines and comics and worked for magazines such as Estampa and Blanco y Negro.

After moving back to Mexico he landed his first job working for the magazine “Sucesos para todos”. In 1954, (and up until 1970) he joined Imprenta Galas de Mexico producing commercial advertising and calendar artwork commissioned by Cigarrera La Moderna. During this period he was known for spending long stretches in his studio, painting whenever inspiration found him, regardless of the hour.

Much of his work reflected his own fascination with Aztec Mythology, Catholicism, pin-up girls and the diverse Mexican landscape. In 1940, he created what is arguably the most famous amongst his paintings, La Leyenda de los Volcanes, which was inspired by the legend of Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl.

He continued to paint privately and illustrate for various clients until his death on December 5, 1971. His last published artwork was Las Mañanitas. His art continues to be celebrated in Mexico, Spain and the United States.

Queer iconography

El Tonalamatl Ollin

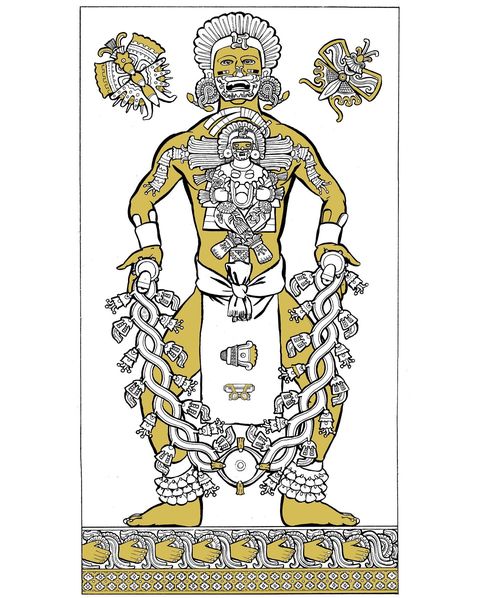

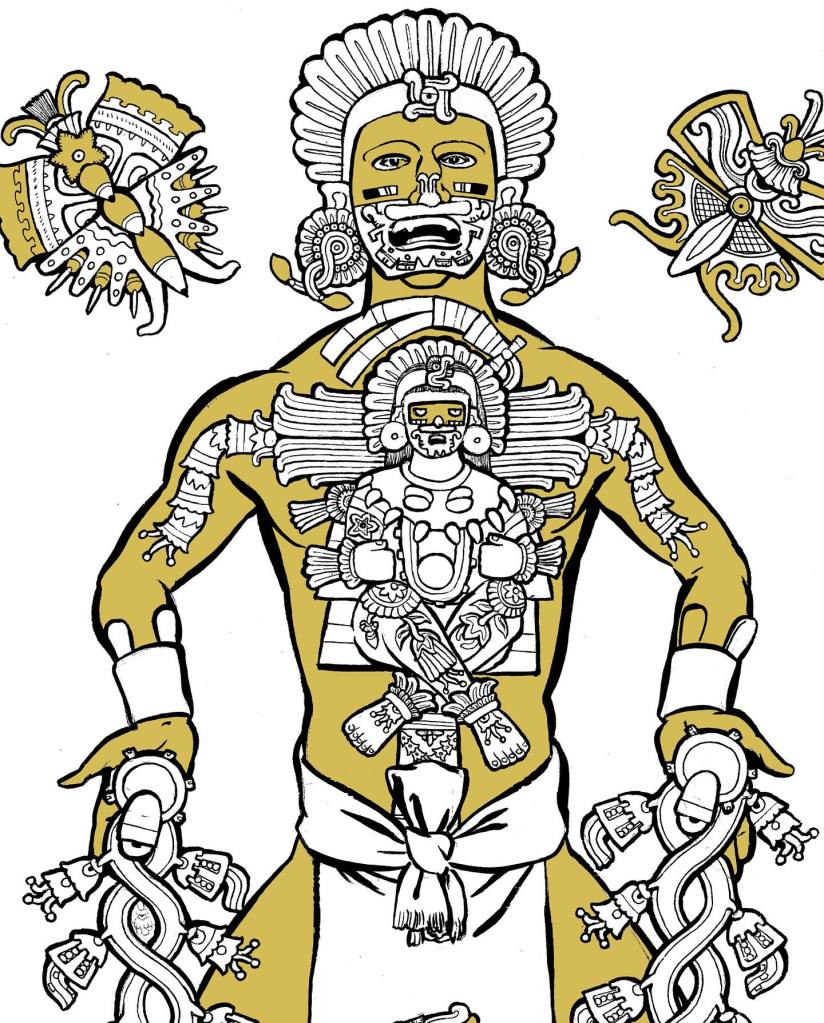

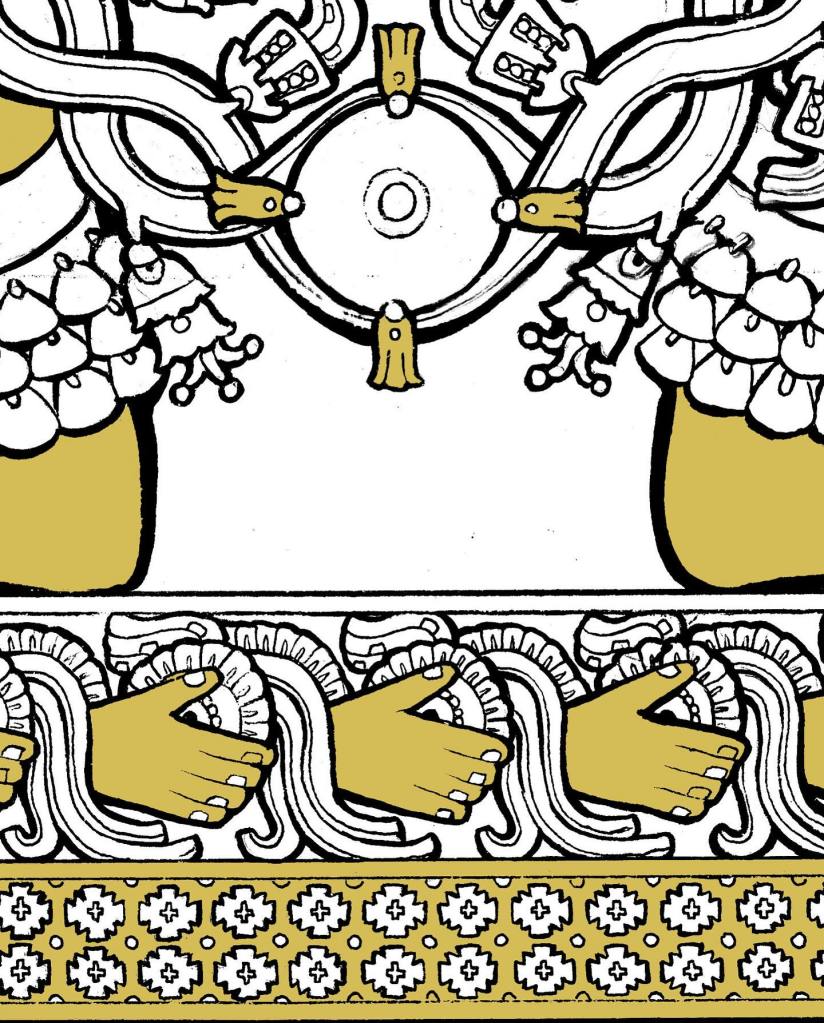

This is a new design for a set of regalia I am making, specifically meant for xochihua or two spirit people. A xochihua is a person who is assigned male at birth, but who takes on aspects of a third gender as they age. They might appear similar to a trans woman, or a gender fluid person. Xochihua means “possessor of flowers,” and describes this third gender. They are ruled by Xochipilli, the Prince of Flowers, who is the Teotl of joy, art, hallucinogenic plants, and the morning sun. The drawing is for a maxtlatl, or loincloth, but the regalia will also include a skirt which can be worn with it. In the drawing, a young man stands in a dance-pose, and with the ayoyotes or seed-rattle ankle bracelets of a dancer. Flowers spill from their hands, to indicate that they are xochihua, “possessors of flowers,” while the pattern at the bottom of hands and flowers has the same meaning. Xochipilli appears in his heart, to indicate that he abides there, and rules there, and the dancer wears a mask of Xochipilli as well. Butterflies fly to either side of his head, which are both symbols of Xochipilli and sly allusions to the common anti-gay slur, “mariposa,” in Spanish. I am almost finished designing the other side of the maxtlatl, which features a xochihua person in a skirt, and with Xochiquetzal in their heart. I will also be designing a set of regalia for patlacheh or “possesors of wild cacao.” They are also two spirit, but assigned female at birth but with the characteristics of trans men or gender fluid people. And finally, if you are going to leave hateful comments, please don´t bother! I will erase the comments and block you. I don´t tolerate hate or the colonized mindset which cannot accept our ancient gender diversity

El Tonalmatl Ollin is a perfect example of colonisation from within. This concept first entered my consciousness from listening to the podcast “From the Margins”. This podcast is primarily architecturally based and discusses perspectives on the built environment with a particular focus on the borderlands. In one episode they discuss decolonisation, as is often bought up when discussing (usually) white, European based cultures and the effect they have had on the world. Now decolonisation itself is an odd term as it refers to an historical event (or series of perhaps still ongoing events) that cant be undone. You can’t take back history. It has passed and it is over. You can however change the future by creating a new history so instead of decolonising perhaps we should be looking at re-indigenising? This however is problematic too as there is still a huge amount of racism attached to indigenous cultures and this is where I have a problem as people don’t want to re-indigenise they just want to colonise in a different matter and this is what I see occurring here with Xochipilli and Tonalmatl Ollin. From the Margins discusses the colonisation of México from within México itself.

Tonamatl Ollin is openly queer in a vast amount of his (David Gremard Romero) artwork and has forcefully imprinted this personality on making Xochipilli not only homosexual but the God of homosexuality. This is not supported by the history of this particular force of nature any more than is Wassons insistence that Xochipilli is a god of hallucinating plants. Both theories have some merit as Xochipilli does have some floral imagery that relates to hallucinogenic plants but recent research does not fully support his claims. Xochipilli also does have some feminine attributes but this is not at all uncommon in Mesoamerican philosophies when you take into consideration the thoughts regarding balance in the universe that runs through (in this case) the Mexica worldview. Tonalmatl Ollin will not tolerate any view beyond his own which he states he will erase and block you as he does not “tolerate hate or the colonized mindset” all while colonising an “indigenous” worldview with his own queer one. How is this any different?

Two other aspects of David’s explanations that are problematic and disingenuous are the descriptors of flowers and butterflies. Speech was very important amongst the Mexica. So much so that the speakers of the Náhuatl language were called nahuatlacah or the “clear speaking ones”. Speech was quite formal, and witty, clever speaking (such as clever double entendres)(1) were valued, as was poetic speech. This speech was also referred to as “floral” so a possessor of flowers might indicate nothing more than a witty, poetic and eloquent speaker.

- A double entendre is a figure of speech or a particular way of wording that is devised to have a double meaning, one of which is typically obvious, and the other often conveys a message that would be too socially unacceptable, or offensive to state directly

When we come to butterflies you will find they were not symbolic of homosexuality but were symbolic of the souls of the dead, in particular warriors who were slain in battle or women who died in childbirth (1). The symbol of the butterfly or mariposa might now be used to indicate homosexuality (particularly effeminate homosexuality) but this was not the case in Mesoamerica during the time of the Mexica and the worship of Xochipilli. Various dictionaries on the subject note that “The first written reference of butterfly related to male homosexuality is the 16th century, done by Pedro de León, Jesuit confessor to the prison of Seville, in the book “El apéndice de los ajusticiados” (Appendix of executed). Pedro de León compared the men who practiced sodomy with the “mariposillas” (little butterflys), that tempted by the light of the flame get too close and ended up burning, as well it happens to the sodomites, who just burned at the stake.”

- a woman who died in childbirth was considered to have perished whilst fighting a great battle and went to the same heaven to that of fallen warriors

Corazon mexica

The Tlatoani and the Warrior

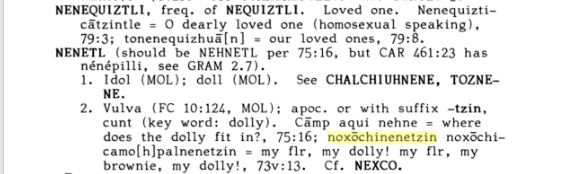

In classical Nahuatl, a “Xōchihuah,” or, “a possessor of flowers,” can be loosely understood to represent a queer man or trans woman. While concepts like “gay” do not translate across cultures, people whom we would understand to be queer did exist in the Aztec past. “Xochitl,” or “Flower,” symbolizes pleasure and femininity. Flowers could symbolize breasts in Aztec poetry, or, for example, in song 75 of the Cantares Mexicanos, a woman calls her vagina “noxōchinenetzin” meaning “my little flower doll. These uses of the word Flower suggest that flowers are equivalent to the female aspect of being. The meaning of the term Xōchihuah suggests that those who “possess flowers” engage in activities traditionally understood to be feminine, from gay sex, to dressing in female garb, to living lives as what we would consider trans women. In numerous sources, it is told that families frequently recognized their children as Xochihuah, and raised them as such, allowing them to dress in feminine clothing, and learn the social roles of a third gender. Other terms used to describe what we might consider a gay man are “Cihuayollotl,” or “Heart of a Woman,” and “Cuiloni.” While at least one text suggests harsh penalties for same sex behavior, others say that Xochihuah people could play the role of caregiver, priest, shaman, concubine, and teacher, and that they held a role in society that accepted and honored their place as people suspended between the male and female principles. Both attitudes can be true. Mesoamerica was an enormous place, whose cultures lasted many millennia, and it is surely the case that some moments in Mesoamerican history and culture were repressive, and others accepting, just as is the case today in the West.

Here, two Cihuayollotl men, a Tlatoani, or king, and a Jaguar Knight, enjoy the love they feel for one another. The Tlatoani wears his turquoise diadem, which is the traditional crown of a ruler, while the warrior wears a jaguar helmet, whose nose is pierced with a turquoise nose-ring denoting bravery. An image of love in ancient Mexico.

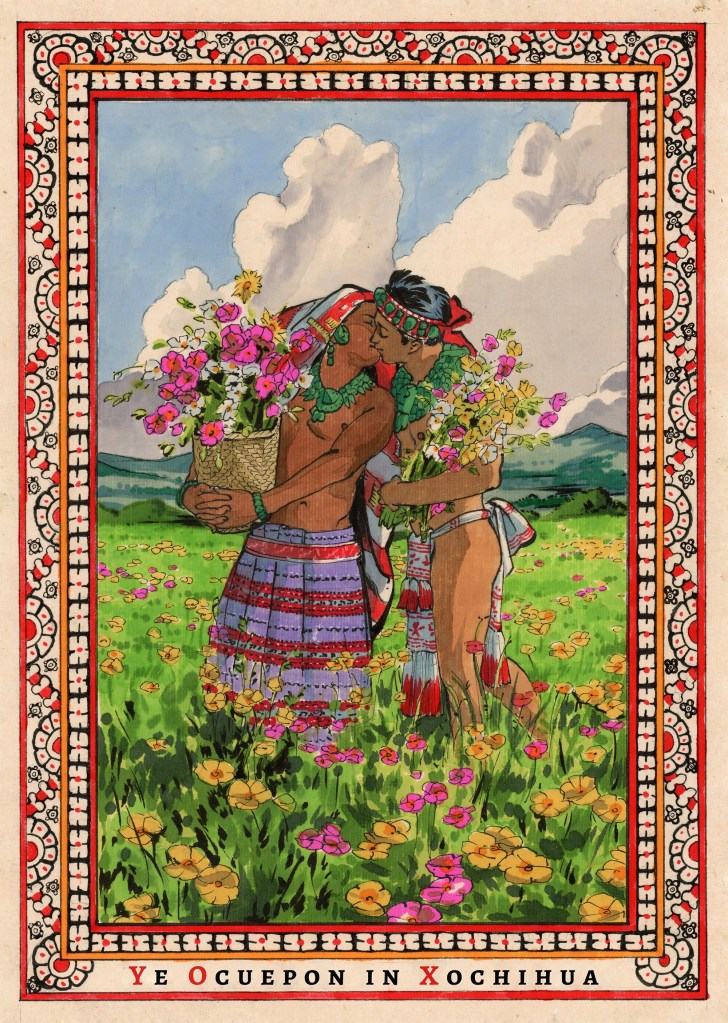

Felix de leon

In ancient Nahua or “Aztec” culture, xochihua, owner of flowers, was the name given to queer people assigned (1) male at birth. For this culture, flowers were a sign of femininity, sexuality and beauty. To be an “owner of flowers” marked you as a person linked to the feminine realm of culture and being, and marked you as a third gender, neither male nor female but both. To our eyes xochihua people might appear similar to a trans woman, or a gender fluid person, encompassing elements of both genders. In this painting, a xochihua person carries a large basket full of flowers. They wear a skirt, and because of the heat, they have removed their huipil, or traditional blouse, and wear it covering their head. They exchange a kiss with their lover, a man. The phrase in the Nahuatl language, “Ye Ocuepon in Xochihua”, means “The Xochihua has Blossomed”.

- “assigned” is an interesting word here and it is often used in these type of discussions. In Mexica culture your personality was often understood to be directly affected by the day sign under which you were born (in a manner very similar to that of astrology as it is understood today) and it was believed that there was no escaping this influence. For example if you were born under the day sign 2 rabbit then it was expected (and maybe even lamented) that you were destined to become a drunkard. This is not the same as being born of a specific biological sex (i.e. male or female). Even though within Aztec culture specific roles were required of both males and females there was no “assignation” as such of sex at birth. This is simply an observation, and as for “queerness”, this can neither be assigned or even observed at birth as children at this stage are blank slates (regardless of their day signs or astrology).

In a later posting of this image (1st April 2024) (an Aprils Fools Day joke?) Corazon Mexica notes “Today is International Trans Visibility Day so here are some paintings which I made for my community! While there really was no “trans” identity, as such, in the prehispanic past, many indigenous nations did have 3, 4, 5, and even more genders whom they recognized and respected”

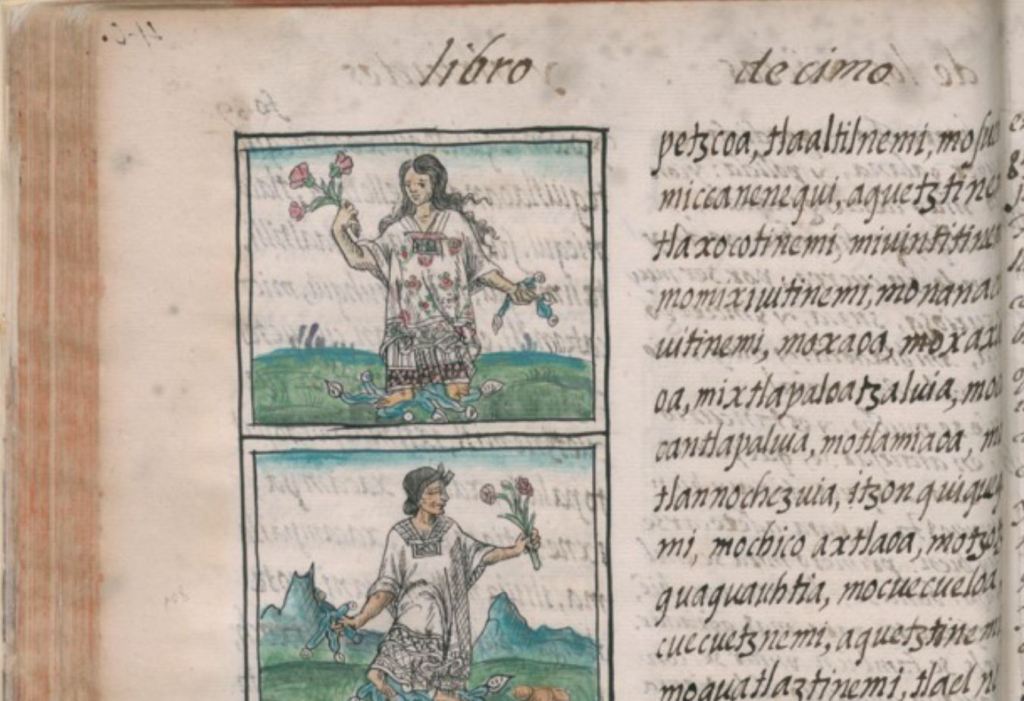

This word “xochihua” arises frequently in discussions centred on Xochipilli so lets examine it a little.

xochihua

Etymology – From xochi(tl) (“flower”).

Noun – xochihua

- (literally) flower-bearer

- seducer, seductress

- The term applied to a cross-dressing figure depicted, and described as having androgynous qualities, in the Florentine Codex. (Whitehead 2007)

xochihua.

Principal English Translation: : a pervert; also, a person’s name (attested male)

Orthographic Variants: : xochioa, xuchioa, suchioa, Xochiva

Attestations from sources in English:

in suchioa cioatlatole, cioanotzale = The pervert [is] of feminine speech, of feminine mode of address. (central Mexico, sixteenth century)

Fr. Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain; Book 10 — The People, No. 14, Part 11, eds. and transl. Arthur J. O. Anderson and Charles E. Dibble (Santa Fe and Salt Lake City: School of American Research and the University of Utah, 1961), 37.

ymota ytoca xochiva = father-in-law named Xochihua (Cuernavaca region, ca. 1540s)

The Book of Tributes: Early Sixteenth-Century Nahuatl Censuses from Morelos, ed. and transl. S. L. Cline, (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center Publications, 1993), 142–143.

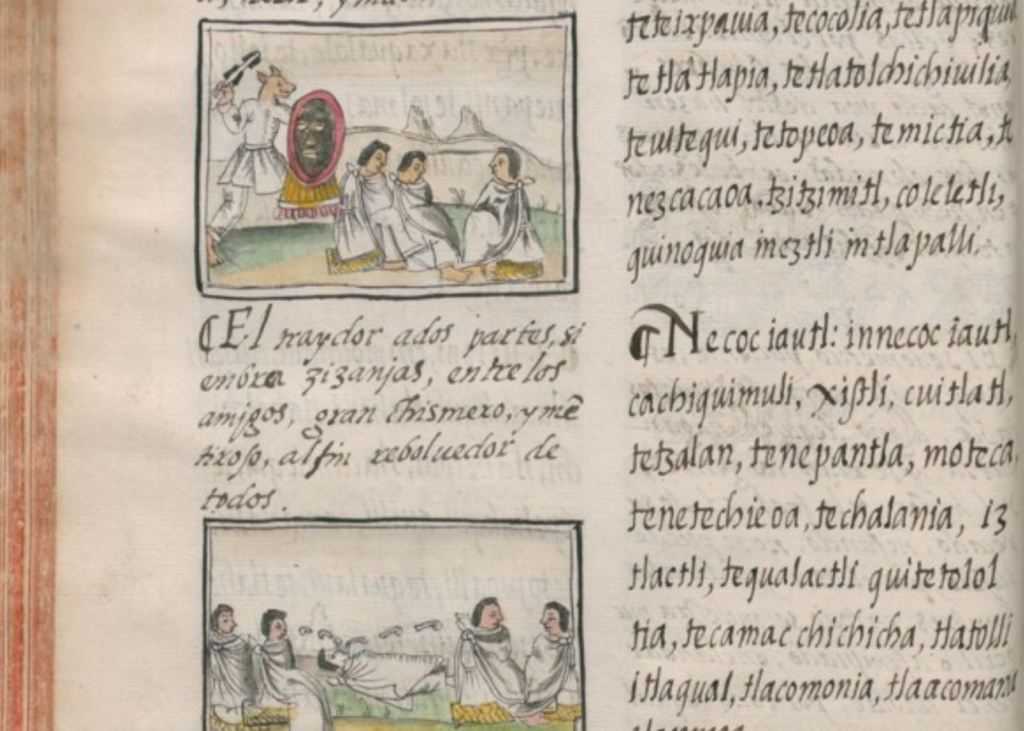

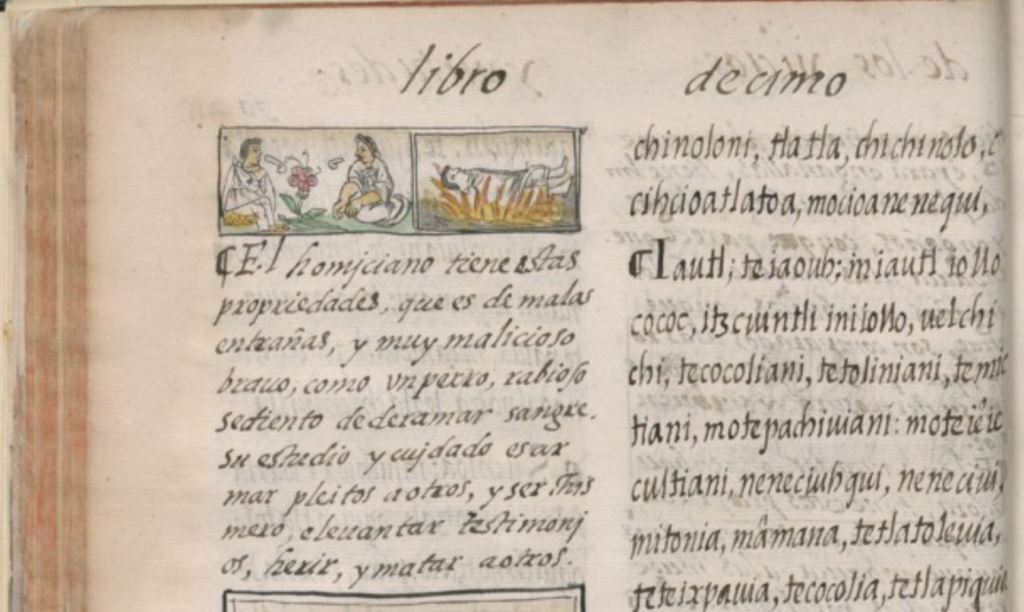

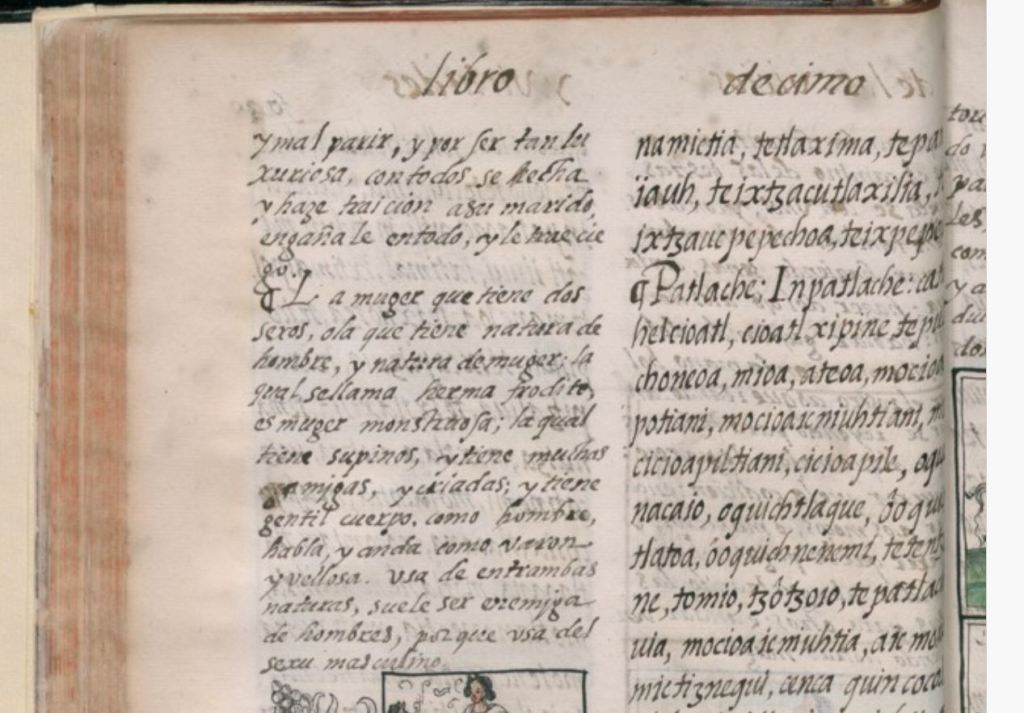

Florentine Codex

The Florentine Codex is a 16th-century ethnographic research study in Mesoamerica by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Sahagún originally titled it La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España (in English: The General History of the Things of New Spain). After a translation mistake, it was given the name Historia general de las Cosas de Nueva España. The best-preserved manuscript is commonly referred to as the Florentine Codex, as the codex is held in the Laurentian Library of Florence, Italy.

In partnership with Nahua elders and authors who were formerly his students at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, Sahagún conducted research, organized evidence, wrote and edited his findings. He worked on this project from 1545 up until his death in 1590. The work consists of 2,500 pages organized into twelve books; more than 2,000 illustrations drawn by native artists provide vivid images of this era. It documents the culture, religious cosmology (worldview) and ritual practices, society, economics, and natural history of the Aztec people. It has been described as “one of the most remarkable accounts of a non-Western culture ever composed.”

Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson were the first to translate the Codex from Nahuatl to English, in a project that took 30 years to complete.

xuchihua

teocuitla icpac xuchihua.

Principal English Translation: a crowned king or queen (Molina 1571)

Orthographic Variants: teocuitlaicpac xuchihua, teocuitlaicpac xuchiua, teocuitlaicpac xochihua, teocuitlaicpac xochiua

Alonso de Molina: teocuitlaicpac xuchiua. rey o reyna coronada.

Modern Mexican incarnations

Issuing bank Bank of Mexico (Banco do México)

Period United Mexican States/Mexican Republic (1823-date)

Type Standard banknote

Years 2000-2009

Value 100 Pesos

Currency New Peso (1992-date)

Two security strips:

One 1.0mm embedded with repeating “CIEN” within oval at left obverse.

One 1.0mm embedded solid strip near centre.

UV activity:

Obverse

National arms inside a D-Shaped circle, with weight and silver purity at bottom outside the circle.

Reverse

Inside a D-Shaped circle the figure of Xochipilli (Prince of flowers), which in the Mexica culture is the god of love and beauty.

One of the few coins that made the leap between Old and New Pesos. Coin was minted under the new currency keeping design and size, only face value changes from $100 to N$5

Estampas

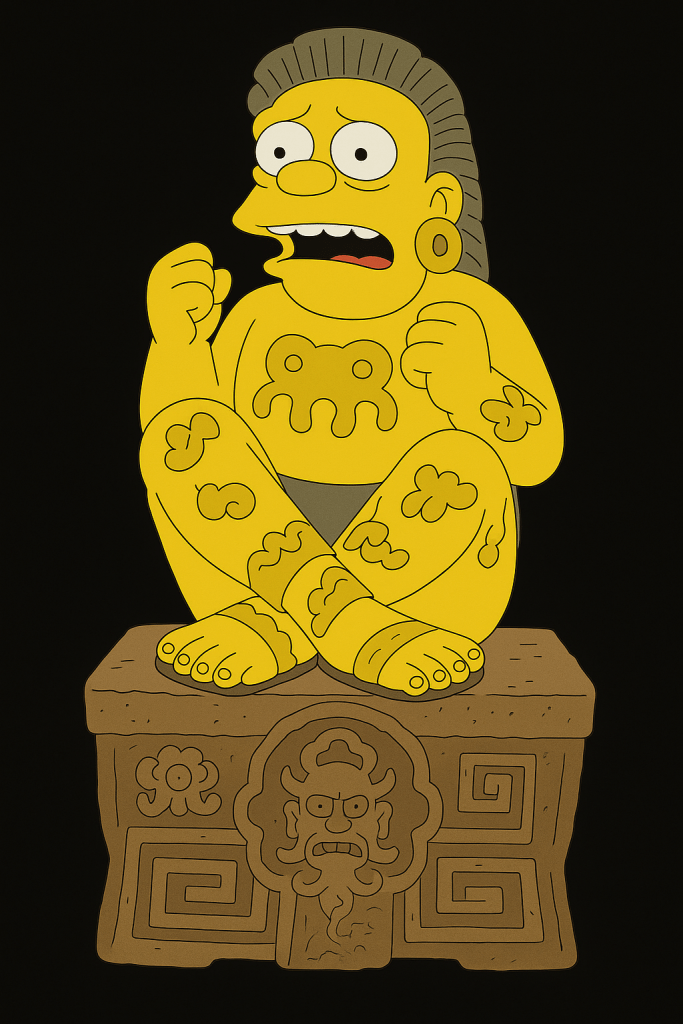

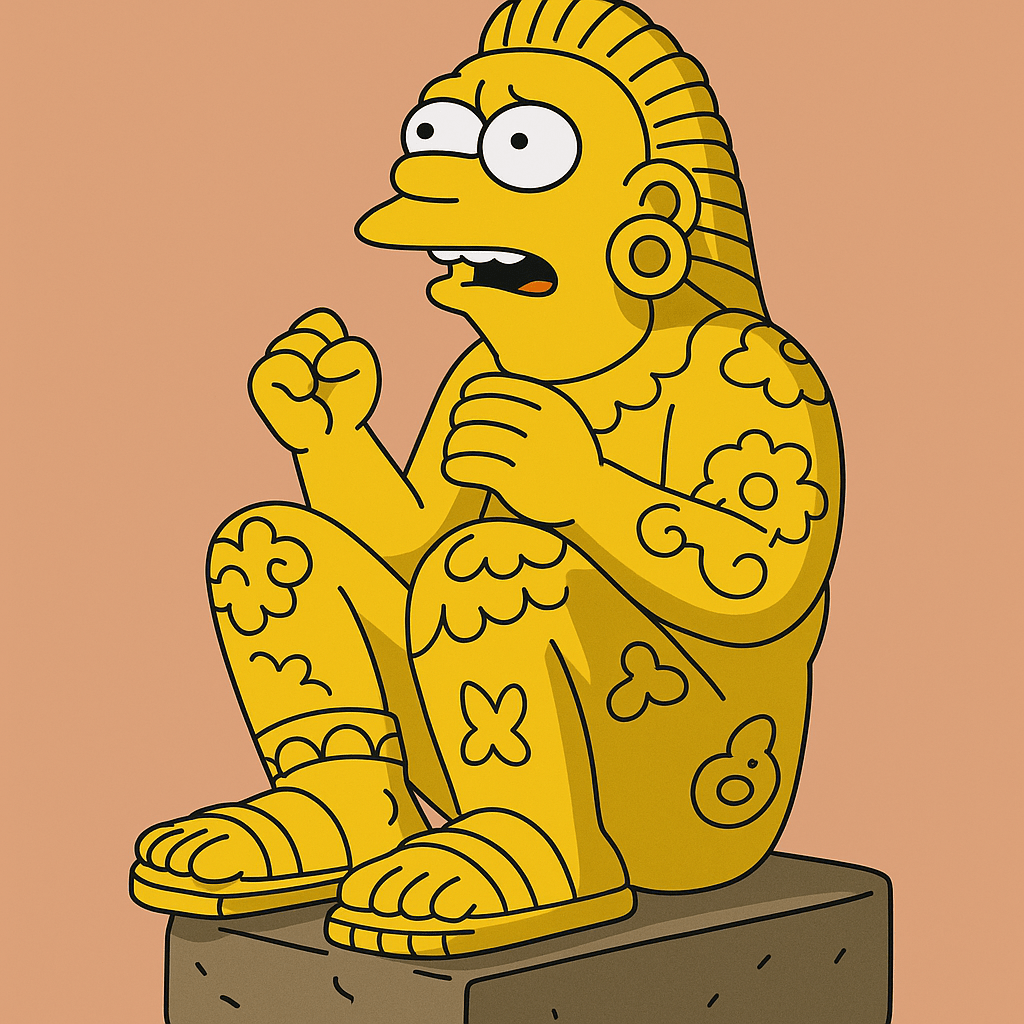

A.I. Strikes Again

The latest art craze to hit the market (April 2025) is the use of A.I. (artificial intelligence) through the use of Chat GPT to create computer generated images in certain styles. I did this (only a little) with the animation styles of Studio Ghibli and the Simpsons.

For some reason A.I. sees fear in Xochipillis visage.

He makes for a happy Muppet though

Xochipilli also makes for an excellent tattoo design

Art by JAES a multimedia artist from Margaret River in Western Australia https://www.instagram.com/jaes777/?hl=en

Image by KRIPTIK an artist from Western Australia. https://www.instagram.com/kriptik333/?hl=en

Study continues

References

- Angelini, Ivana & Gratuze, Bernard & Artioli, Gilberto. (2019). Glass and other vitreous materials through history. 10.1180/EMU-notes.20.3.

- Bierhorst, John (1985) A Nahuatl-English Dictionary and Concordance to the ‘Cantares Mexicanos’ With an Analytic Transcription and Grammatical Notes : ISBN: 9780804711838

- CASO, A. and S. MATEOS HIGUERA; 1937. Cataloguo de la collection de monolitos del Museo Nacional de Antropología perdeciente al INAH. Mexico DF: INAH

- CHAVERO; A. 1958. México a través de los siglos: historia general y completa del desenvolvimiento social, político, religioso, militar, artístico y literario de México desde la antiguedad mas remota hasta la epoca actual, t.1: Historia antigua y de la conquista . Mexico DF: Director of publication D. Vincente Riva Palacio, 1st edition: 1887, Editorial Cumbre, SA

- FERNANDEZ; J. 1959. “Una aproximación a Xochipilli”. in Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl. 6 lams. Mexico: I: 31-41. 1 they

- López Luján, Leonardo; Talavera González, Jorge Arturo; Olivera, María Teresa & Ruvalcaba, José Luis. (2016) El buril de un orfebre de Moctezuma (The burin of a goldsmith of Moctezuma) “Azcapotzalco y los orfebres de Moctezuma”, Arqueología Mexicana, núm. 136, pp. 50-59.

- Mathiowetz, Michael D.. (2018). A History of Cacao in West Mexico: Implications for Mesoamerica and U.S. Southwest Connections. Journal of Archaeological Research, (), –. doi:10.1007/s10814-018-9125-7

- Molina,Alonso de; (1571) Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, 1571, part 2, Nahuatl to Spanish, f. 100v. col. 1.

- PEÑAFIEL; A. 1910. Destruction of the Mayoral Temple of Mexico Antiguo and the monuments encountered in the city, in the excavations of 1897 and 1902. Mexico: Imprenta y Fototipia de la Secretaria de Fomento

- Pomedio, C. (2005). XOCHIPILLI, PRINCE DES FLEURS. De l’Altiplano Mexicain à La Patagonie, Travaux Et Recherches à l’Université De Paris I, Cyril Giorgi (Coord) BAR International Series 1389.

- Santos Hipólito, Daniel et al ., “A discovery in Santa María Cuepopan”, Mexican Archeology , no. 159, p. 9.

- Sahagún, B. D. (1577) General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex. Book XI: Natural Things . [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified] [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667856/.

- SCHULTES, RE and A. HOFMANN; 1979. Plants of the Gods. New York: McGraw-Hill Book

- WASSON; G. 1980. The Wondrous Mushroom: mycolatry in Mesoamerica. New York: McGraw-Hill

- Whitehead, Neil. L; editor (2007), “Sexual Encounters/Sexual Collisions: Alternative Sexualities in Colonial Mesoamerica”, in Ethnohistory (in Classical Nahuatl), volume 54, number 1, Winter

Websites and Images

- Daniel Santos Hipólito, Eder Arias Quiroz and Salvador Pulido Méndez. They belong to the Archaeological Salvage Directorate, INAH. – https://arqueologiamexicana.mx/mexico-antiguo/noticia-un-hallazgo-en-santa-maria-cuepopan

- Lugares INAH – https://lugares.inah.gob.mx/en/museos-inah/exposiciones/18016-2094-el-hallazgo-de-xochipilli-macuix%C3%B3chitl-en-el-antiguo-barrio-de-santa-mar%C3%ADa-cuepopan.html

- Mariposilla – https://www.moscasdecolores.com/en/gay-dictionary/spanish/mariposon/

- Mexico Daily Post – After being buried for five centuries, the Xochipilli-Macuilxóchitl is exhibited in the Museo del Templo Mayor – https://themexicocitypost.com/2021/12/20/xochipilli-macuilxochitl/

- Milenio – Dios del amanecer enriquece acervo del Templo Mayor – https://www.milenio.com/cultura/arte/templo-mayor-dios-del-amanecer-enriquece-acervo

- The young god of music , song and dance – https://www.mundoclasico.com/articulo/33088/undefined#google_vignette

- Visitor in front of the statue of Xochipilli, the Aztec god of music – https://musikschulwelt.de/archiv/7062-musikwelten-in-mannheim

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Museum_Volkenkunde_Aztec_exhibition_5.jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Reiss-Engelhorn-Museum-Nord-MA.jpg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mannheim_Reiss-Engelhorn-Museum_Weltkulturen_D5_20100809.jpg

- https://arqueologiamexicana.mx/mexico-antiguo/el-buril-de-un-orfebre-de-moctezuma?fbclid=IwAR1W_nv4YwqgHF1t8zi41Qi9PQxKa4cCj-mFG_qwkp_WiftO7HUslffn2bY_aem_AeBJzxvSAbInsJFinpwaRG93_jkhJtlQYCmsG9C9h7lg7Bho7Ob2BHY86TXCB17IHWuXyXPagqrBIKPFFoeZabA4

- xochihua. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/xochihua

- xuchihua – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/teocuitla-icpac-xuchihua

- Image burin 213 – By Didier Descouens – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10299570

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burin_%28engraving%29

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burin_(lithic_flake) - Image cambridge binary 283 – Shea JJ. Lithics Basics. In: Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East: A Guide. Cambridge University Press; 2013:17-46.

- Image burin spall – https://arnesaknussemm.wixsite.com/arnesaknussemm/single-post/2015/02/07/burins-the-chisels-of-the-late-ice-age

- Image aguila real by Águila Real Mexicana via facebook – https://www.facebook.com/aguilarealmexi/photos/a.419495928149682/4648193778613188/?type=3

- Image hocofaisan – https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hocofais%C3%A1n_%288708251591%29.jpg#filelinks

- Image – cojolite (Crested guan) Pava cojolita (Penelope purpurascens) – https://www.inaturalist.org/guide_taxa/538787

- Image – Corazon mexica – The Tlatoani and the Warrior – https://x.com/FelixdEon/status/552984401651331072

- Image – El Tonalamatl Ollin – https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=857420326430092&set=pcb.857420369763421

- Image – Ye Ocuepon in Xochihua – https://x.com/MiCorazonMexica/status/1774531430535594353

- Teocalli (Xochipilia) – https://escapadas.mexicodesconocido.com.mx/atractivos/la-xochipila/#gallery-1

- El centro ceremonial de Xicotepec estaba dedicado al dios Xochipilli – mixtecosymigrantes.blogspot.mx

- Xochipilia (APROMECI) – https://apromeci.org.mx/blog/post/99/Xochipila._El_lugar_de_Xochipilli#_ftn1