Joyous Yuletide. Well it’s not Christmas but today certainly feels like it. I was scanning Facebook Market place (as I do) to find anything remotely Mesoamerican and mask related when I stumbled across the painting below. I was also quite surprised that it was listed as being FREE. This I could not believe so I contacted the seller and after a little back and forth I indeed scored this item for free.

The seller posted the painting as being “Inca painting on canvas purchased while on holiday in Cusco Peru“. She could offer me no further information other than that she purchased it in 2014.

The painting appears festive in nature with the figure on the left playing an Andean flute and the central figure a drummer.

The figure on the right of the painting is holding green leaves (coca?)

Coca leaves?

In Peru, coca leaves (1) have a deep cultural, historical, and spiritual significance, traditionally used for medicinal, social, and religious purposes by Andean cultures for millennia. Coca leaf use in South America dates back at least 8,000 years (Dillehay et al 2010). Archaeological evidence for the chewing of coca leaves dates back at least to the 6th century AD Moche period, and the ensuing Inca period, based on mummies found with a supply of coca leaves, pottery depicting the characteristic cheek bulge of a coca chewer, spatulas for extracting alkali and figured bags for coca leaves and lime made from precious metals, and gold representations of coca in special gardens of the Inca in Cuzco.

- Coca, (Erythroxylum coca), tropical shrub, of the family Erythroxylaceae, the leaves of which are the source of the drug cocaine.

Coca leaves and coca tea are legal and part of daily life in Peru but legality varies by country; it is legal in some South American countries like Colombia, Bolivia, and Argentina, but it is illegal in the United States unless decocainized.

Researching this image on Google I was only able to discover a few images.

Dynamic Oil Painting On Canvas

Artist Signed Armando

Cusco – Peru 2015

I have to say that Armandos work bears great similarity to my painting

The only other images I could find in this style. None were credited with an artists name.

Escritor en Bicicleta – Flickr

artist unknown

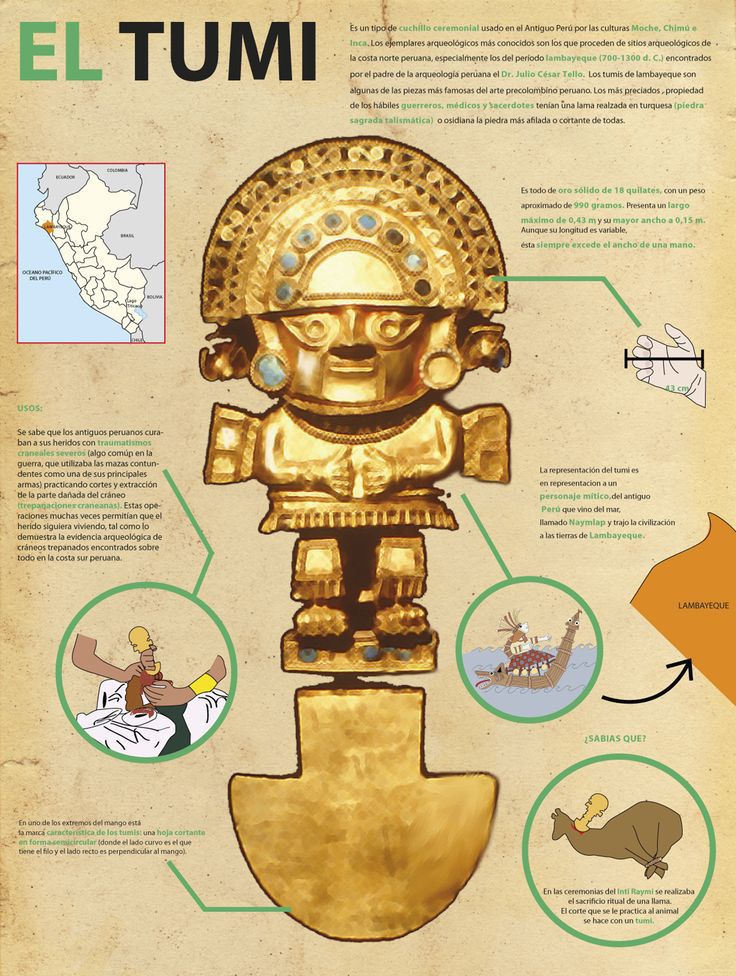

Some of these images bought to mind an image of a headdress as worn in Peru and the surgical (and sacrificial, which I guess is a kind of surgery) implement called a “tumi” (above left) and (above centre) I note the inclusion of an image of Viracocha (Wiracocha).

The Gate of the Sun, also known as the Gateway of the Sun (in older literature simply called “(great) monolithic Gateway of Ak-kapana”) (1),is a monolithic (2) gateway at the site of Tiahuanaco by the Tiwanaku culture (3), an Andean civilization of Bolivia that thrived around Lake Titicaca in the Andes of western South America

- also called the Pumapuncu / Puma Punku Gate – Gate of the Puma

- The defining feature is that the entire structure or sculpture originates from a single, massive stone

- Tiwanaku (Spanish: Tiahuanaco or Tiahuanacu) is a Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia, near Lake Titicaca, about 70 kilometers from La Paz. The site was first recorded in written history in 1549 by Spanish conquistador Pedro Cieza de León while he was searching for the southern Inca capital of Qullasuyu.

The Tumi is a ceremonial knife made of bronze, gold, silver or copper and usually made of one piece. Its handle has a rectangular or trapezoidal shape, its length varies but it always exceeded the width of a hand. At the bottom there is a sharp semicircular blade.

The tumi has been adopted by the government of Peru as a symbol to promote tourism. Many people in Peru hang a tumi on their walls for good luck.

Its image is recognized worldwide and appears in jewellery, handicrafts, and even Peruvian medical institutions, recalling its ancient connection to health and healing.

The Chimú people, who made this ceremonial knife (image above left), inherited the artistic traditions developed by the earlier Moche. The Moche people of northern Peru were among the first to use copper, often with the addition of arsenic to harden the metal and improve the quality of the cast.

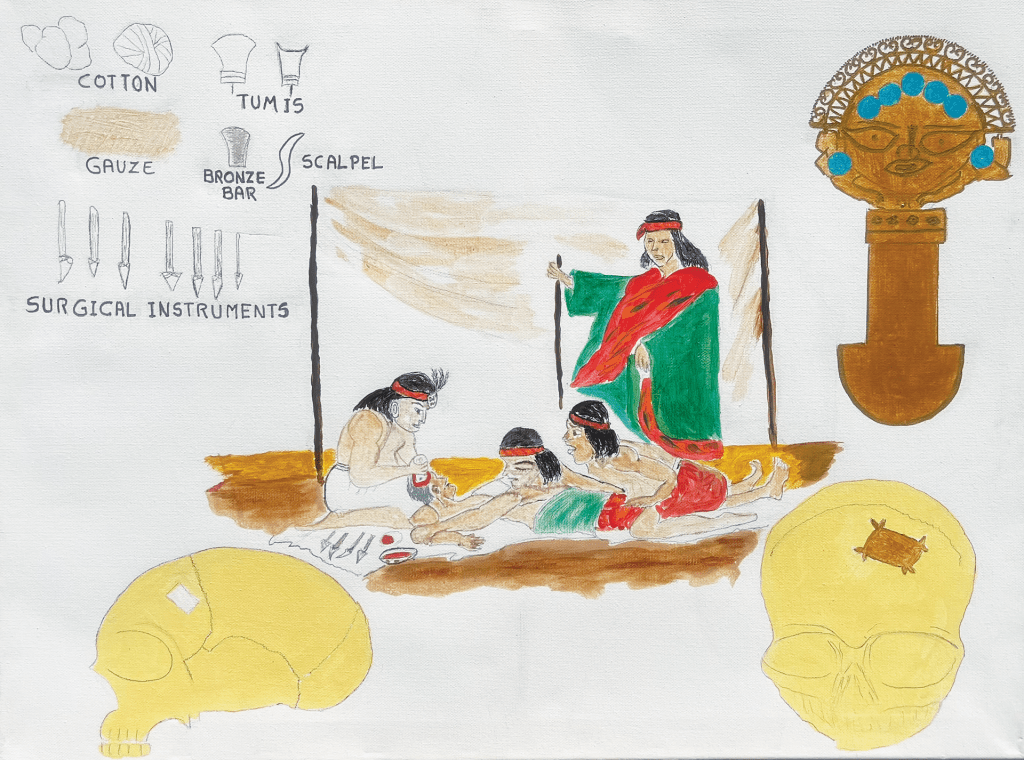

At the time of the Spanish incursions into the Americas there existed within these countries medical knowledge and practices superior to anything that existed within Europe. Knowledge of human anatomy, herbal medicine and surgical practice was so far in advance of that of the Europeans that Hernán Cortes purportedly stated that the Aztec physicians were so superior that the king need not bother sending Spanish physicians to the New World. One area in which they excelled was the treatment of battle wounds (makes sense coming from a culture that thrived on war). This skill was not limited to the Mexica peoples alone.

An area of surgical expertise that the Peruvian peoples were known for is the procedure known as trepanation (1). Trepanation is a surgical intervention in which a hole is drilled or scraped in the human skull for a number of reasons, most notably to treat head trauma caused in battle (Finger et al 2001) (Verano 2016) such as depressed skull fractures caused by clubs or slung stones. It has also been suggested that the procedure was used to treat conditions such as epilepsy, headaches, and other disorders that caused pressure within the skull and multiple trepanations may have been intended to treat headaches, convulsions, or other intracranial mass disorders (Verano 2016). The success of this procedure is evidenced by skulls found with multiple trepanations without fractures. Today this type of surgery is known as a craniotomy (Kushner et al 2018).

- also known as trepanation, trephination, trephining or making a burr hole (the verb trepan derives from Old French from Medieval Latin trepanum from Greek trúpanon, literally “borer, auger”),

The Incas performed trepanations using bifacial, obsidian tools to create incisions in patients’ skulls (Kushner et al 2018) (Gonzales-Portillo 2000). In later years, bronze and copper tools were used for these same procedures. The preferred surgical tool was the tumi, a curved metal knife that cut through skin and the pericranium (1).

- the periosteum (a dense layer of vascular connective tissue) enveloping the skull.

It is known that Andean cultures such as the Paracas or Inca have used tumis for the neurological procedure of skull trepanation.

A 2018 study by Kushner and colleagues analyzed 800 trepanned crania and compared the degree of healing of the Peruvian trepanations with the trepanation practices during “other ancient, medieval, or American Civil War periods.”3 This study concluded that in ancient Peru (400–200 BC), the long-term survival rate was 40% and improved to a high of 91% (1000–1400 AD). The average survival rate was determined to be 75%–83% during the Inca period (1400–1500 AD).3 Kushner compared these findings to the American Civil War, when the average mortality rate was 46%–56% in cranial surgeries. The high survival rates during the Inca Empire may be attributed to procedures being performed in open-air environments, the use of herbal medication, and single-use tools (Kushner et al 2018)

Other Peruvian (?) pieces in my collection

These two containers (above and below) were purchased in Peru in the 1960’s

This is known as a portrait “stirrup” (1) bottle popular in the Moche culture (2). These high-status, finely crafted bottles were made using moulds and hand-finishing techniques, showcasing a glossy surface and often depicting portraits of real individuals, possibly warriors or elites, who were central to Moche society and belief systems.

- A unique, bifurcated spout that resembles a horse’s stirrup is a defining characteristic of these vessels.

- The Moche culture (also known as Mochica) arose and flourished between the northern coast and the valleys of ancient Peru, in particular, in the Chicama and Trujillo valleys, (with its capital near present-day Moche, Trujillo, Peru) between 1 and 800 AD.

Tourist pieces

This piece of cloth (a little over 2 metres long) was found by a friend in a thrift store in Western Australia. She picked it up for me as it looked vaguely “Mexican” to her. Viracocha (1) is part of the recurring pattern. It is also quite thin but incredibly warm.

- Viracocha is the supreme creator deity in ancient Andean mythology, particularly among the Inca, responsible for creating the sun, moon, stars, earth, and all living beings, including humans. After creating his creations and shaping the world from Lake Titicaca, he wandered the land teaching people skills and culture before departing across the Pacific Ocean, leaving behind a promise to return. He is depicted as a bearded man and was revered as the ancient one and the father of other Inca gods. This story is very similar to some legends of Quetzalcoatl (2)

- Quetzalcoatl, meaning “Feathered Serpent” in Nahuatl, is a major deity in Mesoamerican cultures, particularly among the Aztecs, who associated him with the morning and evening star, wind, knowledge, arts, and merchants. He was a benevolent god, a patron of the priesthood, and the “god of life, light, and wisdom”. Depicted as either a feathered serpent or a bearded man, he is seen as a symbol of renewal, transformation, and civilization.

References

- Carroll, Eleanor. (1977) Coca: The Plant and its Use : National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph. 1977 May ; Series 13:35-45. PMID: 408701. – http://sad.health.org/pub/AD03991.pdf (Full Monograph – https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-HE20-PURL-gpo117636/pdf/GOVPUB-HE20-PURL-gpo117636.pdf)

- Chavez-Rivera, Angel D. & Sanchez, Tiffany R. (2022) Trepanation Reveals the Success of the Incas : https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/news-publications/news-and-articles/bulletin/2022/november-december-2022-volume-107-issue-11/from-the-archives/

- Dillehay TD, Rossen J, Ugent D, Karathanasis A, Vásquez V, Netherly PJ (2010). “Early Holocene coca chewing in northern Peru”. Antiquity. 84 (326): 939–953. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00067004. S2CID 162889680

- Faria, Miguel. (2013). Violence, mental illness, and the brain – A brief history of psychosurgery: Part 1 – From trephination to lobotomy. Surgical neurology international. 4. 49. 10.4103/2152-7806.110146.

- Finger S, Fernando HR. E. George Squier and the discovery of cranial trepanation: A landmark in the history of surgery and ancient medicine. J Hist MedAllied Sci. 2001;56(4):353-381.

- Kushner DS, Verano JW, Titelbaum AR. Trepanation procedures/outcomes: Comparison of prehistoric Peru with other ancient, medieval, and American Civil War cranial surgery. World Neurosurg. 2018;114:245-251.

- Marino R, Gonzales-Portillo M. Preconquest Peruvian neurosurgeons: A study of Inca and Pre-Columbian trephination and the art of medicine in ancient Peru. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(4):940-950.

- Saville, Marshall H. (Translator) (1917) Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan (The Chronicle of the Anonymous Conquistador) written by The Anonymous Conqueror, a companion of Hernán Cortes.

- Verano JW. “Why Peru?” in Holes in the Head: The Art and Archaeology of Trepanation in Ancient Peru. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2016.

Websites

- Coca: The Sacred Leaf (Image) : https://tdaglobalcycling.com/2015/09/coca-the-sacred-leaf/

- Exploring the Pan Flute in Peru: Culture and History (Image) : https://x-tremetourbulencia.com/exploring-the-pan-flute-in-peru-culture-and-history/

- Moche Culture : https://www.tierrasvivas.com/en/moche-culture-peru

- The Tumi: The Mysterious Sacred Knife of Ancient Peru Between Power and Healing : https://peruanos.nl/en/the-tumi-the-mysterious-sacred-knife-of-ancient-peru-between-power-and-healing/

- Tumi, the ceremonial knife : http://www.discover-peru.org/tumi-knife-culture/