In a previous Post (Rábano. The Radish.) I mentioned briefly the dish known as pozole (go check the Post out for a bit of a breakdown on the origin and meaning of the word pozole, it’s interesting – well I reckon it is anyway – and it links with a little more etymology in this Post)

Anyway.

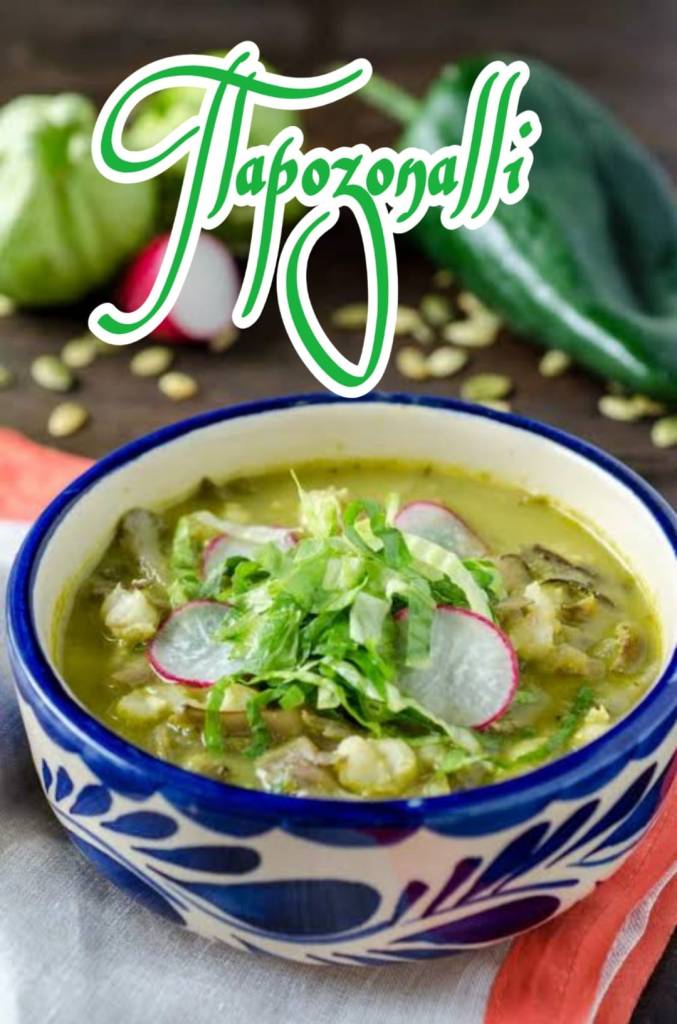

Back to the Pozole. At its most basic it is a soupy pork dish in a chile based “sauce” most noted for the inclusion of a specific type of corn called cacahuazintle or hominy (as it would be in the U.S.A.) (1)

- The most prolific descriptions of the source of this word all expressed (almost verbatim) “1620-1630 AD, first recorded by Capt. John Smith, probably from Powhatan (Algonquian) uskatahomen, or a similar word, “parched corn,” probably literally “that which is ground or beaten.” A site on Woodland Indian Educational Programs notes “The word hominy is derived from the Virginia Indian term “rockahominy” possibly referring to corn or parched corn meal. It was shortened to “hominy,” creating the popular term we use today”

This corn is also intimately connected with the name of the dish.

To recap.

Pozole comes from the Nahuatl word posolli. Posolli is defined as a stew made of maize kernels. Pradeau (1974) notes that the word derives “from the Nahuatl “pozol” which means frothy or foamy and refers to the phenomena that the dried kernels of cacahuazintle cause the cooking water to “foam up”.

I also found (from a couple of American websites – which was interesting) an expansion on this definition (which was also interesting as it didn’t come up at all in my initial research) “the word pozole comes from the Nahuatl potsoli which means foamy and apotsoli would mean foamy water”. Hey, but that is what research is for right? These sites also strongly emphasised the practise of cannibalism (more on this later).

A Mexican Government website notes in an article on pozole not that the water foams up during cooking due to something in the corn that makes the water foam, but relates it to the physical structure of the corn itself. Think popcorn (but popped in a soup)

“From the Nahuatl pozolli, from tlapozonalli, meaning foamy (1), it is a broth made from cacahuazintle corn kernels, which is precooked for two hours. In this process, the corn kernels lose the fibrous husk that covers them and when they boil, they open like a flower, which gives them a foamy appearance.“

- although the Nahuatl dictionary I often refer to indicates the word tlapozonalli means “boiled” and posolli (or pozolli) means “foam”

So. Which definition?

¿Porque? indeed.

Now, back to these American websites and their salacious tales of cannibalism both of which stated, verbatim…..

“According to research by the National Institute of Anthropology and History and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, on these special occasions, the meat used in the pozole was human.[4](sic) After the prisoners were killed by having their hearts torn out in a ritual sacrifice, the rest of the body was chopped and cooked with corn.”

Now this was obviously cut and pasted from somewhere (one of the sites failed to remove an in text reference marker – [4]) and I have yet to find this quote (No, it’s not from Wikipedia – I checked)

Wikipedia reckons “According to research by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH – the National Institute of Anthropology and History) and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), on these special occasions, the meat used in the pozole may have been human. Possible archaeological evidence of mass cannibalism may support this theory“, which is kind of similar but even their references lead nowhere.

Both articles also make an interesting link with corn and human flesh

“corn was a sacred plant for the Aztecs and other inhabitants of Mesoamerica, pozole was made to be consumed on special occasions. The conjunction of corn (usually whole hominy kernels) and meat in a single dish is of particular interest to scholars because the ancient Mexicans believed the gods made humans out of masa (cornmeal dough)”.

and that

“The meal was shared among the whole community as an act of religious communion. After the conquest, when cannibalism was banned, pork became the staple meat as it “tasted very similar” (according to a Spanish priest)

The research on the subject is contradictory. Most will note (in one form or another)….

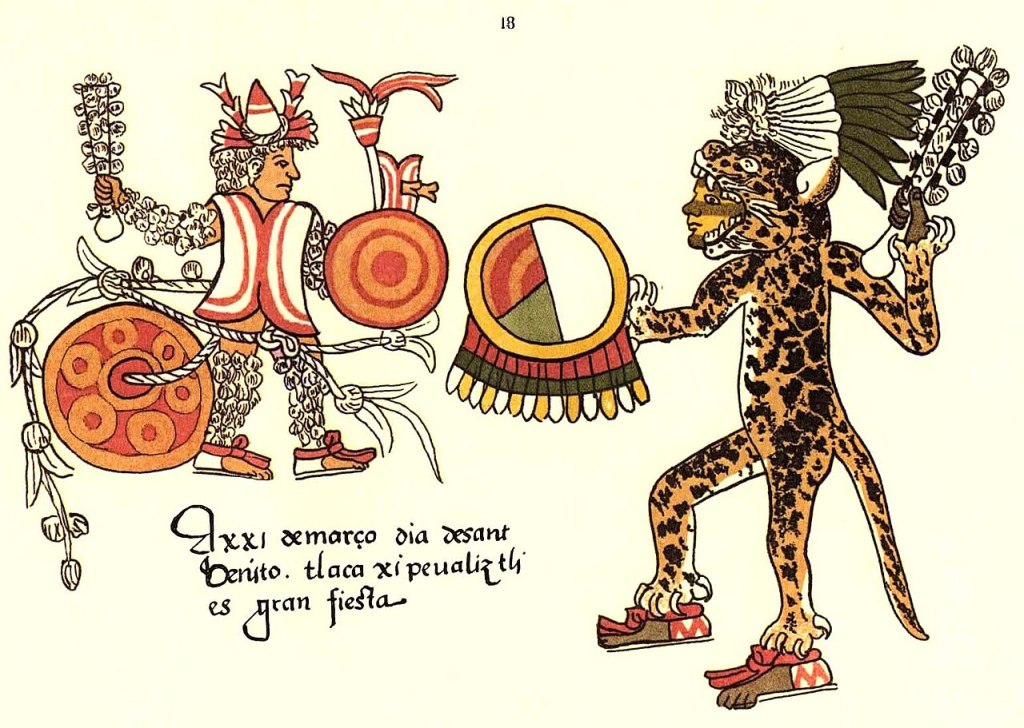

“In ancient times, pozole was consumed during the Tlacaxipehualiztli, which meant the skinning of men, which was a time dedicated to the god Xipe Totec “Our Lord the Skinned” (1) and a time in which the Aztecs carried out several sacrifices between warriors, where they fought to the death.

- for more information on Xipe Totec (and masks made of human skin) see Xochipilli. The Prince of Flowers

…and that…

“In these rituals, the hearts of those being sacrificed were first removed, and then consumed as part of the ritual. According to some historians, the Aztecs would have consumed human flesh along with corn kernels, which would be known today as the pozole we all consume.“

but…..

“Although some historians are unsure, it is believed that not all Aztecs consumed human flesh and that most citizens never tasted it, as only royalty, priests, and the upper class ever ate it.”

and…

“Although many historians have rejected the idea that the Aztecs ever ate human flesh, researchers have found that many bone remains show signs of exposure to direct fire or boiling; in addition, cut marks (1) have also been found on the bones.“

- which is probably not unusual because if you were dispatched by the weapon known as the macuahuitl, which was a wooden weapon (looking much like a cricket bat) adorned with wickedly sharp obsidian blades there would undoubtedly be cut marks in the bones of the slain (just a theory on my behalf)

This would make the game more interesting

Other historians note that……

During Tlacaxipehualiztli gladiatorial sacrifices took place, unequal combats (1) between war captives and elite Mexica warriors on a temalacatl – a cylindrical sculpture engraved with solar motifs. Captured warriors slain in this manner would certainly bear “cut marks on their bones”

- unequal in that the opponent was tied to a stone which hampered their movement and was armed with a macuahuitl that was edged with feathers rather than obsidian blades.

It was also noted that the captive held a special significance and was to be honoured

“The warrior could not consume his prisoner, as he took on the role of father and protector from the moment of capture until the moment of sacrifice. This also happened with captives who were sacrificed by removing their hearts. The viscera were discarded,” and implore us to “remember that the flesh of the prisoner sacrificed on the altars of the temples, in the presence of the gods, was transmuted into something sacred, something exposed to divinity. This ritual could also be called Teocualo, “devouring the god” (1)

- for more on the ritual consumption of Gods flesh see Amaranth and the Tzoalli Heresy

Food too rich for the campesinos? Judging by the language used, the festival celebrated and the god venerated perhaps this consumption was for only the priestly classes? maybe some upper classes or royalty too?

Other sources note that this (the cannibalism) is nothing more than a smear campaign instigated by the Spanish simply to demean the people so as to justify their own abuses. Other versions indicate that what was boiled in pozole was not human flesh, but rather a xoloitzcuintle, a hairless breed of dog domesticated and raised for human consumption.

I do briefly talk about pozole in my Post A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Diet. In this I mention one theory that the “itzcuintli” in this case is not the xoloitzcuintli but the tepezcuintle or the lowland paca.

I’d also like to look at some more of the imagery used in these articles.

Now, all of the hubbub seems to surround one character, Xipe Totec, and his celebration, Tlacaxipehualiztli or the “Flaying of Men”.

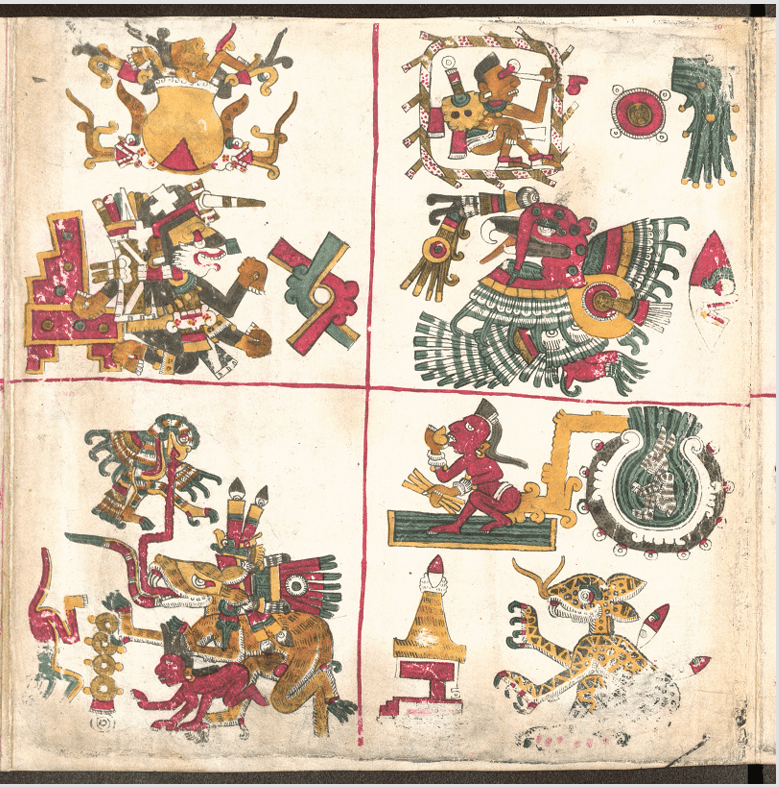

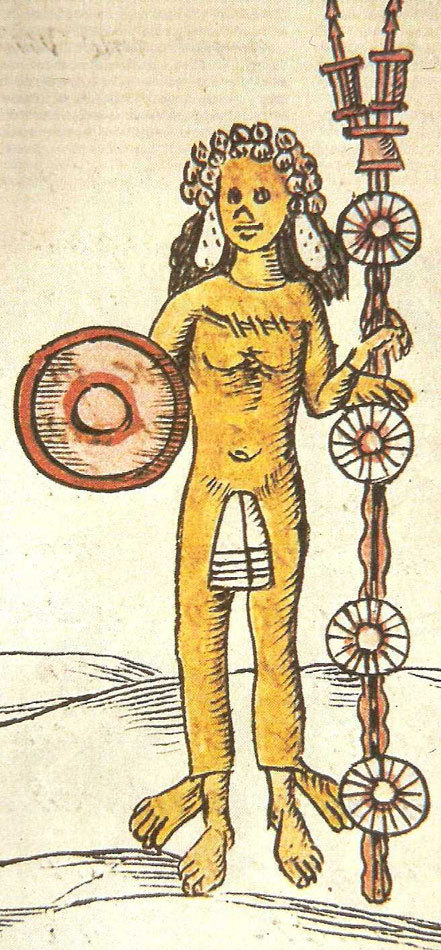

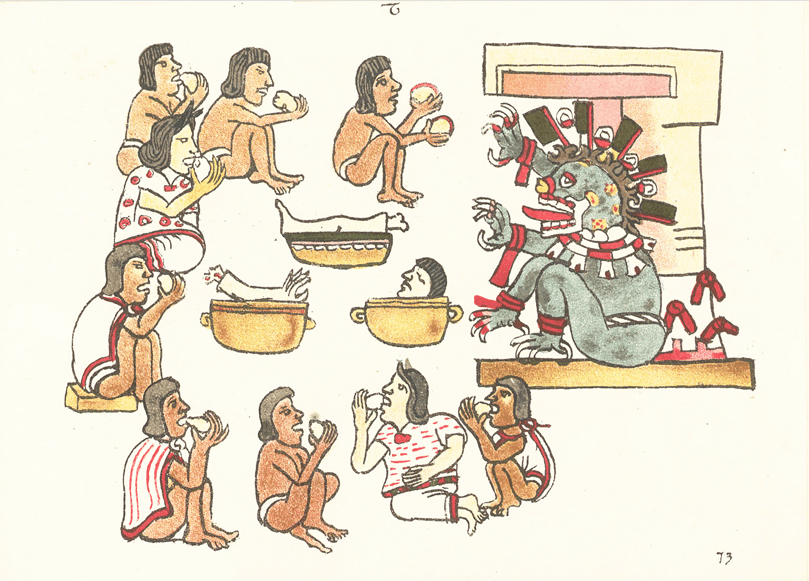

Various depictions of Xipe Totec (or priests of Xipe Totec) wearing human skin

To recap

During Tlacaxipehualiztli, the second ritual month of the Aztec year, the priests killed human victims by removing their hearts. They flayed the bodies and put on the skins, which were dyed yellow and called teocuitlaquemitl (“golden clothes”)(1). Other victims were fastened to a frame and put to death with arrows; their blood dripping down was believed to symbolize the fertile spring rains. A hymn sung in honour of Xipe Totec called him Yoalli Tlauana (“Night Drinker”) because beneficent rains fell during the night; it thanked him for bringing the Feathered Serpent, who was the symbol of plenty, and for averting drought.

- these yellow painted, human skin cloaks represented corn. They were worn for 20 days, until they began to rot and fall off, and represented the sprouting of the maiz kernel through its own skin and the surface of the soil.

Now there is no denying that (according to modern standards) the Azteca were pretty loose and definitely violent in a way that cannot be understood today (I mean skinning a person and then wearing that skin as part of a religious rite??) but cannibals?

Aside from (perhaps) ritual cannibalism relating to the priestly class there is very little spoken of the practice by the Mexicans (although they weren’t called that at the time) themselves. There are however a few (three specifically) mentioned by two Nahuatl scholars (1) who chronicled various aspects of history of the people of the Americas (also not called that at the time) for the Spanish.

- Tezozomoc and Chimalpahin

Hernando Alvarado Tezozomoc (1) (1980)(1998) and Francisco de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin (3) (1965)(1983)(1991)(1997) are two prominent early Nahua scholars who do mention three stories of cannibalism by trickery in the Valley of Mexico (4) . These three stories are the only, passing, mentions of cannibalism in their entire body of work.

- Hernando (de) Alvarado Tezozómoc was a colonial Nahua noble (died 1606) . He was a son of Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin (governor of Tenochtitlan) and Francisca de Moctezuma (a daughter of Moctezuma II) and the grandson of the great emperor, Moteuczoma Xocoyotzin (Motecuzoma the Younger, The ninth and third to last of the Mexica Tlatoani). Alvarado Tezozomoc was definitely a generation or two older than Chimalpahin. There is no known birthdate, but his father, Huanitzin, died in 1541, indicating that Alvarado Tezozomoc was at least thirty-eight by the time Chimalpahin was born in 1579 in Amecameca. Tezozómoc worked as an interpreter for the Real Audiencia (2). Today he is known for the Crónica Mexicayotl, a Nahuatl history

- A Real Audiencia or simply an Audiencia, was an appellate court in Spain and its empire. An appellate court is a court that reviews decisions made by lower courts, such as trial courts, to correct errors of law or fact. Unlike a trial court where new evidence is heard and facts are determined, an appellate court focuses on reviewing the legal and factual basis of the lower court’s decision, which can lead to the reversal or modification of the original ruling.

- Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin , or simply Chimalpahin (1579-1645 approx.) was an indigenous Nahua historian of New Spain, belonging to the Chalca nobility. The most important of his surviving works is the Relaciones or Anales. This Nahuatl work was compiled in the early seventeenth century, and is based on testimony from indigenous people. It covers the years 1589 through 1615, but also deals with events before the conquest and supplies lists of indigenous kings and lords and Spanish viceroys, archbishops of Mexico and inquisitors

- one each in occurring in Xochimilco, Chalco, and Tenochtitlan

These three tales are practically the only form in which cannibalism appears in the major Nahua writings of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The stories portray cannibalism as shocking, even abhorrent, to Aztecs (rather than as customary) and was potentially used as a stratagem for humiliating an enemy or provoking a community to war.(Isaac 2005)

The first purportedly occurred circa 1430, following the successful 1428–1430 rebellion of the Tenochca (the people of Tenochtitlan) (1) against the Tepaneca empire. Lords of Xochimilco were tricked into eating a dish containing human flesh (2) (although it is stated that they only ate the broth and were horrified as they neared the bottom of the pot only to find it contained “heads like those of children, [and] human hands and feet, and [human] guts.” The Aztec Tlatoani Itzcoatl is posited to have used this act as an impetus to invade and subjugate the Xochimilca during his reign.

- Azteca, Mexica and Tenocha ae all being used inbterchangeably to describe the Mexica people of Tenochtitlan. See Origins of the words Aztec and Mexico for more on this.

- This also demonstrates the confusion regarding the transmission of these stories. Another version is that the dish was the dish was prepared by Xochimilca women and then fed to the Tenocha visitors (who the Xochimilcans were secretly preparing to rebel against but were allowing them access to their markets as part of their subterfuge)

The second incident purportedly occurred in 1469 or 1473 and stemmed from an attempted coup against the Aztec King Axayacatl of Tenochtitlan by Moquihuix the Tlatoani, of Tlatelolco. Hoping to enlist allies, Moquihuix sent emissaries to various cities both within and beyond the Valley of Mexico. He thought the people of Chalco would aid him but this backfired and the Chalca took his emissaries captive. After slaying the emissaries they were taken to Chalco and cooked. Moquihuix and various other Tlatelolcas [dignitaries] were invited to a banquet so that they would come and eat their own ambassadors, not knowing that they had been killed by the Tenochcas. This incident determined that, during [the next] five years, the Tenochcas and Tlatelolcas made war.

The third story occurs in Tenochtitlan and involves the humiliation of a captured (and famed) Tlaxcallan war captain Tlahuicole. Tlahuicole was a heroic man “of terrible and great strengths, who realized feats and deeds that seem incredible and superhuman” . He was captured by the army of neighbouring Huexotzingo, and presented as a trophy of war to Moctezuma the Tlatoani of Tenochtitlan. Moctezuma so admired Tlahuicole that he offered him command of a large segment of the Aztec army. Tlahuicole accepted and distinguished himself greatly in a six-month war against the Tarascan empire. Moctezuma wanted Tlahuicole to fight in a war that would bring him into contact with his own people but Tlahuicole would be greatly shamed by this so he asked to be sacrificed instead. This was not to be, in the end of this story Tlahuicole is humiliated by being fed a soup containing his own wife’s genitals.

Spanish writers, in contrast, recount versions of two of the three stories of cannibalism by trickery but also liberally lace their narratives with allegations of institutionalized cannibalism in connection with a great many religious and political events (Isaac 2005)

So?

Cannibals or no? Spanish propaganda?

In 2025 the Templo Mayor invites you to an “event”?

Piel y Maiz : Skin and Corn

Desollamiento y Renacer : Flaying and Rebirth

Is this worrying? Only 20 “attendees” required? So it’s a “limited” sacrifice?

What are we celebrating exactly?

We invite you to discover some secrets of Tlacaxipehualiztli, a festival dedicated to Xipe Tótec.

Stay tuned for Part 3 ( well Part 2 really) : Pozole. The Recipe/s

References

- Bernard R. Ortiz de Montellano. “Aztec Cannibalism: An Ecological Necessity?” Science 200, no. 4342 (1978): 611–17. DOI:10.1126/science.200.4342.611

- Broda, Johanna. “Tlacaxipehualiztli: a Reconstuction of an Aztec Calendar Festival from 16th Century Sources.” Revista Espanola De Antropologia Americana, 1970.

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, Francisco de San Antón Muñón (1965) Relaciones originales de ChalcoAmaquemecan, translated from Nahuatl by Silvia Rendón. Fondo de Cultura Económica, Mexico City.

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, Francisco de San Antón Muñón (1983) Octava relación, translated from Nahuatl and edited by José Romero G. Universidad Naciona lAutónoma de México , MexicoCity.

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, Francisco de San Antón Muñón (1991) Memorial breve acerca de la fundación de la ciudad de Culhuacan, translated from Nahuatl and edited by Víctor Castillo F. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City.

- Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, Francisco de San Antón Muñón (1997) Codex Chimalpahin, Vols. 1 and 2, translated from Nahuatl and edited by Arthur Anderson and Susan Schroeder, with Wayne Ruwet. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

- Isaac, Barry L. “AZTEC CANNIBALISM: Nahua versus Spanish and Mestizo Accounts in the Valley of Mexico.” Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 16, no. 1, 2005, pp. 1–10. DOI:10.1017/S0956536105050030

- Mikulska K. THE DEITY AS A MOSAIC: IMAGES OF THE GOD XIPE TOTEC IN DIVINATORY CODICES FROM CENTRAL MESOAMERICA. Ancient Mesoamerica. 2022;33(3):432-458. doi:10.1017/S0956536120000553

- Pradeau, Alberto Francisco. “Pozole, Atole and Tamales: Corn and Its Uses in the Sonora-Arizona Region.” The Journal of Arizona History, vol. 15, no. 1, 1974, pp. 1–7. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41695162. Accessed 12 June 2025.

- Schroeder, Susan. (2011). The Truth about the Crónica Mexicayotl. Colonial Latin American Review. 20. 233-247. 10.1080/10609164.2011.587268.

- Scrimshaw, N.S. & Young, V.R. Sci. Am. 235, 51 (Sept. 1976); M. Flores, Z. Flores, B. Garcia, Y. Galarte, Tabla de Composicion de Alimentos de Centro America y Panama (Instituto de Nutricion Centro America y Panama, Guatemala City, 1960).

- Tezozomoc, Hernando Alvarado (1980) Crónica mexicana, 3rd ed., edited by Manuel Orozco y Berra. Porrúa Hermanos, Mexico City.

- Tezozomoc, Hernando Alvarado (1998) Crónica mexicáyotl, 3rd ed., translated from Nahuatl by Adrián León. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City.

Websites

- ¿El pozole se preparaba con carne humana? Te contamos la historia (Was pozole made with human flesh? We tell you the story.) – https://oem.com.mx/elsoldetampico/tendencias/el-pozole-se-preparaba-con-carne-humana-te-contamos-la-historia-23743525 – September 15, 2022

- Mercado Santa Monica -Contemporary & Traditional Mexican Restaurant – Santa Monica, CA, United States, California – https://www.facebook.com/mercadosantamonica/posts/pozole-nahuatl-potzolli-which-means-foamy-variant-spellings-pozol%C3%A9-pozolli-posol/331426950252914/ – April 5th 2012

- No volverás a comer tranquilo: Esta es la perturbadora historia del origen del pozole que no conocías (You’ll never eat in peace again: This is the disturbing story of the origin of pozole that you didn’t know about.) https://culturacolectiva.com/entretenimiento/historia-origen-pozole/ – June 16, 2025

- Pozole – Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pozole

- Pozole, profunda historia en cada plato (Pozole, a deep history in every dish) – https://www.gob.mx/agricultura/articulos/pozole-profunda-historia-en-cada-plato?idiom=es – September 12, 2021

- Pozolli – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/pozolli

- Rockahominy – http://woodlandindianedu.com/hominy.html

- Tlapozonalli – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/tlapozonalli

- Yxta Cocina Mexicana – Mexican Restaurant – Los Angeles, CA, United States, 90021 – https://www.facebook.com/YxtaLA/posts/10150720428476842/ – April 5th 2012