*well “Tlatoanis” actually if you want to be pedantic about it (and I do)

I briefly look at the masa based drink called atole in my Post Mexican Cooking Equipment : The Molinillo and go into it in a bit more detail in, A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Appendix 1 : Atole, and then expand upon it again in another related Post, A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Appendix 2 : Chocolate Drinks but in all of these meanderings I missed something quite magnificent (this might be due to my status of being a peasant rather than a king (again with the “king”? I thought we’d discussed this?)

This drink, a chocolate based drink (rather than an atole) is considered to be an ancestral (1) but “endangered” drink as “few know of its existence, fewer understand its value and historical significance and the great difficulty in even finding someone who knows how to prepare it” (2). This may be because it was a segregated (3) drink that was intended to be prepared exclusively for the tlatoanis , priests or some nobles.

- from a time long before our grandparents

- https://www.amr.org.mx/noticias.phtml?id=5905

- separated or divided along racial, sexual, or religious lines. Or as is the case here, along a class division

First some etymology (you know how I love that)

atlaquetzalli.

Principal English Translation : fine chocolate, a hot beverage

Composed of…..

atl.

Principal English Translation:

water; a body of water, such as a lake, river, or ocean; floods, flooding (part of a metaphor for war, atl tlachinolli); liquid beverage, even chocolate; urine; fontanelle; also, a calendrical marker

quetzalli (noun) = a beautiful feather; fig., something precious or beautiful (Brinton 1877)

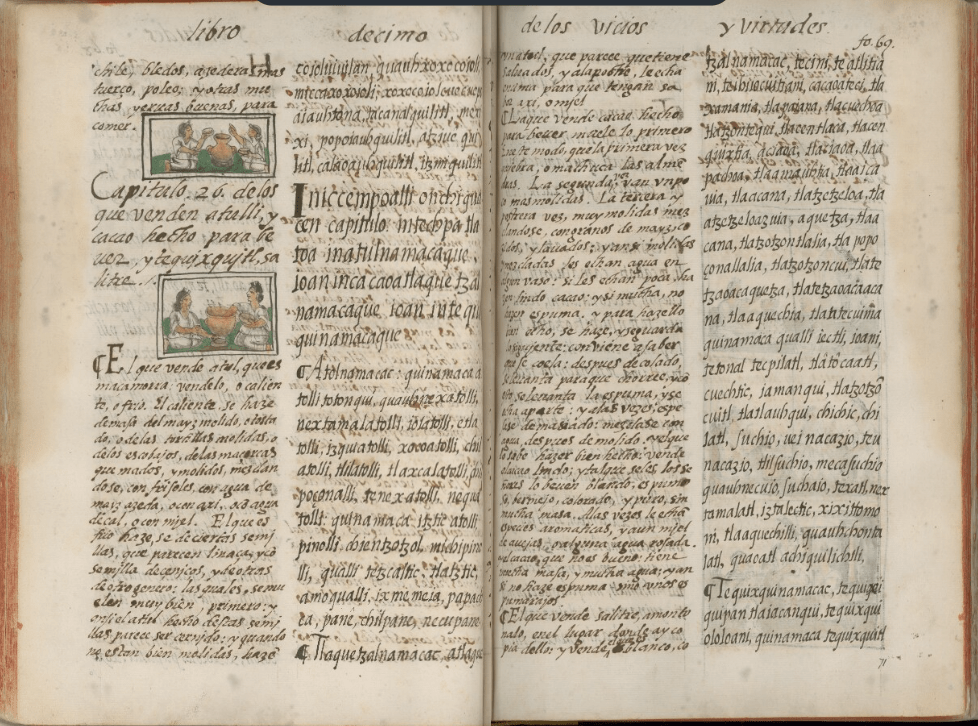

Fr. Bernardino de Sahagún, in the Florentine Codex (1) noted about the seller of atlaquetzalli (2)

- General History of the Things of New Spain; Book 10 — The People, No. 14, Part 11

- the atlaquetzalnamacac “seller of fine chocolate”

“The woman who sells cacao for drinking first grinds it in this way: first, she breaks or crushes the beans; second, they are crushed a little bit more; third and finally, they are finely crushed and then mixed with cooked and washed maize kernels (1). And once [the beans] have been crushed and mixed in this way, they pour water on them in a cup. If they add a little water to them, they make a beautiful cacao, and if [they add] a lot [to them], they do not produce foam. And the following things are carefully done and observed in order to prepare it well: that is, it is strained, and once it is strained, it is lifted up in order to pour it; and this is how the foam rises, and then it is put aside. And sometimes it becomes too thick. It is mixed with water after it is ground. And one who knows how to prepare it well sells a beautiful cacao, such that only the lords can drink it: soft, foamy, vermilion, red and pure, and not too thick. Sometimes they add aromatic spices to it and even bee honey, or else some water mixed with flowers. And cacao that is not good is too thick and has too much water, and so it does not produce foam but only some froth.” (Spanish-to-English Translation)

- the drink being described here is a chocolate atole or what might be now known as champurrado (the name of which derives from the Spanish verb champurrar, which means “to mix” or “to blend” – a word these days used to denote the mixing of spirits/cocktails)

Nahuatl to English differs a little

The admixtures are very interesting

Before the conquest of Mexico the Aztecs used certain spices and aromatic plants in “confectioning their celebrated chocolate”. The mostly highly prized by the ancient Mexicans was the flower called teonacaztli (sacred-ear)(1), or xochinacaztli (ear-flower)

- although this name (teonacaztli) is used to identify another flower (the next one down)

“Uei nacaztli” refers to Cymbopetalum penduliflorum, a Nahuatl term meaning “ear flower” (1) which is a plant used for its dried, cinnamon-like flavour. The use of its flowers as a spice gradually died out throughout the greater part of Mexico with the introduction of cinnamon from the East Indies, which is now, together with vanilla, almost universally used for flavouring chocolate.

- “nacaztli” is the Nahuatl word for “ear”

Safford (1911) notes that “Up to the present day the identity of this plant has remained a mystery. The writer has finally succeeded in tracing it to Cymbopetalum penduliflorum, belonging to the Anonaceae. Cymbopetalum penduliflorum (Dunal) Baillon was called xochinacaztli (ear-flower) on account of the resemblance of its three inner petals to the human ear.“

The ear flower or orejuela is a plant species of the Annonaceae family . It is distributed throughout the high forests of Mesoamerica , from Jalisco in the northwest, to Honduras in the southeast.

Francisco Hernandez, the “protomedico,” sent by Philip II, in 1570, to Mexico to study its resources, has given a fair illustration of the flower (image below), and describes it under the heading “De Xochinacaztli, seu flore auriculae.” This description, in Latin, together with the figure, was published in the “Roman” edition of his work in 1651.

The Spanish edition of Hernandez (1), published by Ximenez in the Mexico City in 1615 notes that “It grows in warm countries, and there is nothing else in the tiangues and markets of the Indians more frequently found nor more highly prized than this flower.”

- See Medicinal use of Papalo in 1651 as noted by Hernández for more information on this protomedico of the Indies

Cymbopetalum penduliflorum medicinal use

The same text notes of the plant (medicinally) that “It is said that when drunk in water this flower dispels flatulency, causes phlegm to become thin, warms and comforts the stomach which has been chilled or weakened, as well as the heart and that it is efficacious in asthma, ground to a powder with the addition of two pods of the large red peppers called texochilli, with their seeds removed and toasted on a comal” and then “adding to the same three drops of balsam and taking it in some suitable liquor.”

Standley (1926) more or less repeats this information (300 years later) “An infusion of the flower petals is drunk to aid digestion and to treat asthma.The petals are highly esteemed as an additive to the chocolate beverage ‘cacáoatl’. The petals not only provide a delicious flavour and pleasant aroma but they are also curative in that the drink reduces flatulence, thins phlegm, and warms and strengthens cold, weak stomachs and hearts”

Teonacaztli (Chiranthodendron pentadactylon), which had the flavour of “black pepper with a resinous bitterness”

Chiranthodendron pentadactylon (medicinal uses)

The flowers have been used in Mexican traditional medicine for centuries, especially in combination with various other medicinal plants, for the treatment of diverse health problems. These include nervousness, epilepsy, headaches, insomnia, depression, dizziness, as an anodyne (for pain), inflammation, ulcers, eye inflammation, piles, and as a stimulant for heart problems (Argueta and Zolla, 2014) (Jiménez, 2012) (Mendoza-Castelán and Lugo-Pérez, 2011) (Quattrocchi, 2012) (Berdonces, 2009) (Mabberley, 2008) (Adame and Adame, 2000) (Johnson, 1999) (Linares et al., 1999) (Argueta, 1994).

The Mayans and other Central American communities have used solutions containing the tree’s flowers as a remedy for lower abdominal pain (Keoke & Porterfield 2002) and for heart problems (Journal of Ethnobiology 1983) (Etkin 2000). Such solutions also reduce oedema and serum cholesterol levels and, because they contain the glycosides quercetin and luteolin, act as diuretics. (Etkin 2000) In Central America and part of Southern Mexico, the flower is extracted in hot water and taken as tea for these medical purposes. Externally, the decoction of the flowers is used as a wash to treat afflictions affecting the pubic area, as well as a poultice to treat haemorrhoids (Gonzalez Stuart)

It was warned however that this drink should not be consumed to regularly or in too great a quantity.

The teonacaztli, or huei nacaztli, was described mostly in connection with cacao. The chroniclers called it an aromatic species or a rose (Tezozomoc 1975) (Sahagun 1956). Cardenas praised the medicinal properties of the chocolate (that included flowers of teonacaztli). Although the drink produced “spirit of life,” he also warned that some preparations of cacao had quite unpleasant mind altering properties, particularly melancholy. The informants of Sahagun, according to Lopez Austin (1974), underlined the hallucinogenic properties of this plant: “… Teunacaztli (teunacacuahuitl, huei nacaztli) … it is taken in cacao … it is a medicine: it drives away the fever. One does not drink it often, and not much, because it takes possession of the people, it inebriates the people just like mushrooms.”

Mecaxochitl – the flowers of Piper amalago, a small vine related to Piper nigrum; Mecaxochitl (rope flower)(cord flower). Also known as Yerba Santa, Mexican Pepper Leaf, or Piper auritum. There are many species of piper referred to as Mecaxochitl, like Piper amalago, these are used interchangeably with other species across the Americas. See my Post Xochipilli : Intoxicating Scent. for more detail on this plant

Piper amalago which in Brazil is known as Pimentinha Branca da Mata or White Pepper of the Forest

It seems that this species of plant (Piper) can provide both anise (1) and black pepper (2) flavour profiles

- Piper auritium – Hoja Santa

- Piper amalgo

Another relative in this family is Piper longum or long pepper

Long pepper is a “sweeter” variety of black pepper (Piper nigrum) with a more lingering heat and (depending on who you ask) an earthy, musky, more pungent (than black pepper) flavour with hints of ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg and/or cardamom.

The Nahuatl translation of Sahagun’s text notes interestingly that the seller of “superior” chocolate that it is reddish (achiote?), bitter (cacao is not naturally sweet), and used chili water. In later translations and critiques of this recipe it is noted that black pepper is the preferred ingredient (over chiles) as it is far superior to the chiles of New Spain.

in Antonio Colmenero’s (1) Curioso tratado de la naturaleza y calidad del Chocolate (1631). He reports on chilis’ use as a chocolate additive. Despite laying out the medical risks of this habit, he gives a thorough recipe (2). He notes that in Mexico the preference is for the hot “Chilparalagua” (elsewhere spelled “Chilpaclagua”) (3) chili whereas in Spain they prefer the broad, milder pimientos de España

- doctor in physicke and chirurgery

- “To every 100. Cacaos, you must put two cods of the long red Pepper, of which I have spoken before, and are called, in the Indian Tongue, Chilparlagua; and in stead of those of the Indies, you may take those of Spaine, which are broadest, and least hot. One handfull of Annis-seed Orejuelas, which are otherwise called Vinacaxlidos: and two of the flowers, called Mechasuehil, if the Belly be bound. But in stead of this, in Spaine, we put in sixe Roses of Alexandria beat to Powder: One Cod of Campeche, or Logwood: Two Drams of Cina∣mon”

- “The other Pepper is called Chilpaclagua, which hath a broad huske; and this is not so biting as the first; nor so gentle as the last (4): and is that, which is usually put into the Chocolate. There are also other ingredients, which are used in this Confection. One called Mechasuchil; and another which they call Vinecaxtli, which in the Spanish they call Orejuelas, which are sweet smelling Flowers, Aromaticall and hot. And the Mechasuchil hath a Purgative quality; for in the Indies they make a purging potion of it. In stead of this, in Spaine they put into the Confection, powder of Roses of Alexandria, for opening the Belly.”

- The other “peppers” being referenced in this text “And concerning the long red Peper, there are foure sorts of it. One is called Chilchotes: the other very little, which they call Chilterpin; and these two kindes, are very quicke and biting. The other two are called Tonalchiles, and these are mo∣derately hot; for they are eaten with bread, as they eate other fruits, and they are of a yellow colour; and they grow onely about the Townes, which are in, and adjoyning to the Lake of Mexico.”

In 1644, Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma published a recipe in his book Curious Treatise on the Nature and Quality of Chocolate the ingredients of which included

- One hundred cocoa beans.

- Two chili peppers (can be substituted with black pepper).

- A handful of anise.

- Anise flower.

- Two mecasúchiles. If you don’t have the previous two spices, you can substitute them with ground Alexandrian roses.

- One vanilla bean.

- Two ounces of cinnamon.

- Twelve almonds and the same number of hazelnuts.

- Half a pound of sugar.

- Annatto to taste.

The recipe was successful and its spread throughout Europe led to widespread consumption, albeit with some modifications that are not worth listing because there were many. However, we will transcribe the introduction that Veryard published in his book Choice Remarks to describe the chocolate recipe: “Since the Spanish are the only people in Europe who have a reputation for making chocolate to perfection, I took it upon myself to learn the method, which is as follows…” The description that continues is of chocolate bars that facilitated the preparation of the drink in the nascent public establishments known as chocolate shops.

Anise is an interesting ingredient in this recipe. It is no doubt an imported ingredient and a substitution ingredient for the original recipe. I have seen several recipes asking for Hoja Santa (or Yerba Santa – Piper auritum) which has an anise flavour profile (although its not that simple). This plant is also a relative of the black pepper (Piper nigrum) and the Mecaxochitl (the flowers of Piper amalago) called for in other recipes/translations. I have also seen Tagetes lucida (or Pericón) called for, another plant which has an anise flavour profile.

Hellmuth (2014) notes these, and others, as chocolate flavourings

The FLAAR (Foundation for Latin American Anthropological Research) report also shows an interesting flower (of which I had not seen before)

This turned out to be the flower of the achiote plant (Bixa orellana) . It is not however the flower that is used but the dried seed, which gives a characteristic redness to the drink (and its own unique flavour)

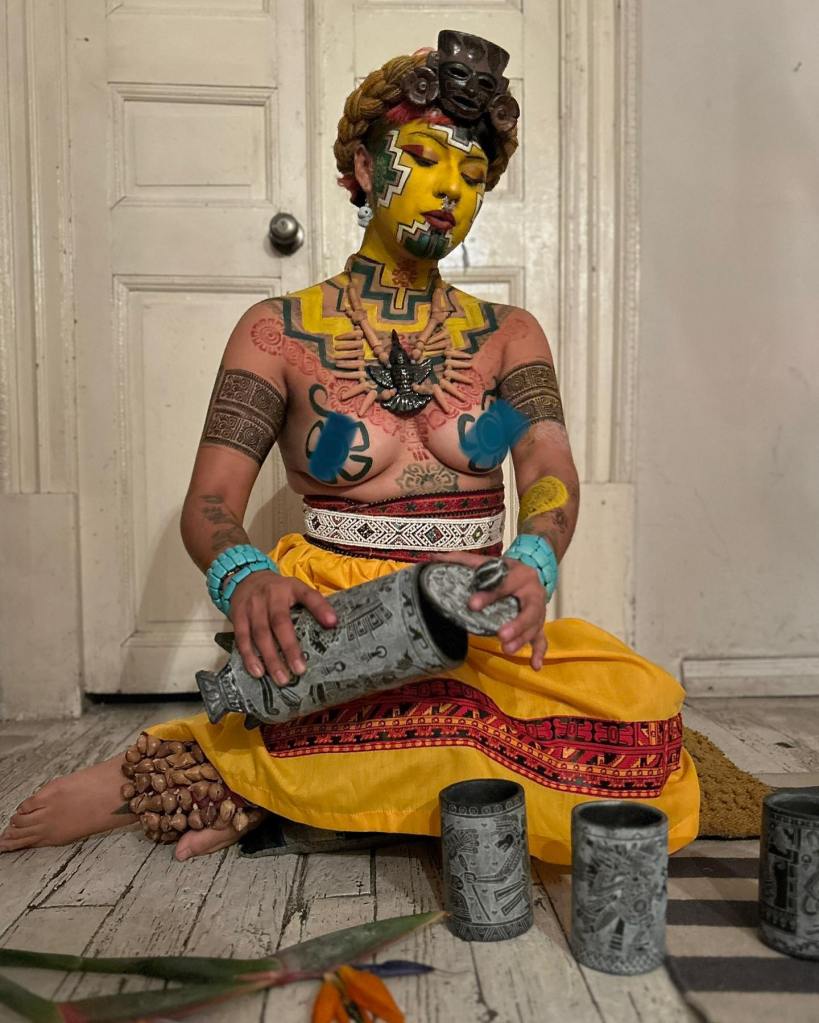

The ahuiani who prepared this drink made it with the following ingredients:

Ahuiani (also Ahwahnee) generally described as a courtesan : in the Aztec world, is the name for the female young entertainers who act as hostesses and whose skills include performing various arts such as music, dance, games and conversation, mainly to entertain male customers, usually Aztec warriors.

- 100 cacao beans

- 2 chilpatlagua chilies or black pepper

- A handful of anise

- A flor de oreja (ear flower – flower of the ear)

- 2 mecasuchiles – If mecasuchiles are unavailable, you can substitute them with 6 powdered Alexandrian roses

- Vanilla

- 2 ounces of cinnamon

- 12 almonds

- 12 hazelnuts

- Sugar to taste

- A little annatto (axiote/achiote) for colouring

Everything is roasted separately (on a comal), leaving the cacao to be the final ingredient roasted. Then, everything is ground and placed in water, stirring until the contents are smooth. To create a foam on your chocolate you can do as they did in mesoamerica

There is also an ingredient substitution in this recipe if you are unable to source mecasuchiles.

Rosas de Alejandría – The Rose of Alexandria.

Now, we’ve got a couple of choices with this plant.

“Rosa de Alexandria” is not a specific known medicinal plant; instead, this phrasing seems to be a general reference to the genus Rosa (rose) with potential references to ancient Alexandria’s historical medicinal uses. The genus Rosa has been recognized for centuries in traditional medicine for its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties, with petals, rose hips, and oils being used for various ailments, including skin issues, inflammation, and digestive problems. This can also refer to the “apothecary’s rose” which has bothe medicinal and culinary use 9and is a different plant)(1)

- The Apothecary Rose, or Rosa gallica officinalis, has been used medicinally since ancient times for a variety of ailments, including digestive issues, skin conditions, inflammation, and even hangovers. Its petals were historically incorporated into syrups, rosewater, and skin treatments, while its rose hips are rich in Vitamin C. The rose’s strong fragrance and potent properties led to its widespread cultivation by monks and apothecaries, making it a symbol of the early pharmaceutical profession.

This (a rose of some variety) is the plant I’m leaning towards

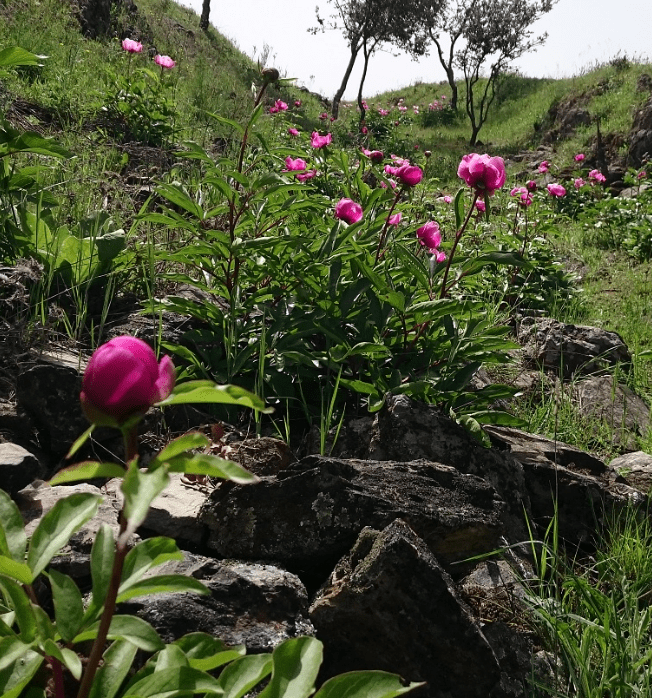

The other Rosa de Alejandría is not a rose species but a peony.

Paeonia broteri

This plant endemic to the Iberian Peninsula . It is found in the mountain ranges of central and southern Spain and in Portugal , where it lives in siliceous or lime-poor areas, in the undergrowth of holm oak , oak , and cork oak forests . Paeonia budori was described by Boiss. & Reut. and published in Diagnoses Plantarum Novarum Hispanicarum , 4, 1842.

The genus name of this plant, Paeonia, refers to a god in Greek mythology. Paeon (or Paieon) was the physician of the gods on Mount Olympus. In Homer’s Illiad, Paean was brought to treat Ares, the god of war, when he was wounded by Diomedes, the hero of the epic. In Homer’s epic, The Odyssey, Paeon also treated Hades after he was wounded by Heracles‘ arrow. The story goes that Asclepius, the god of medicine and healing, flew into a murderous, jealousy fuelled rage after Paeon successfully cured Hades of his wound. To save his life, Zeus transformed Paeon into a flower (the peony por supuesto). This kind of blew up in Asclepius’ face as Paeons name ended up becoming an epithet for the gods Apollo and Asclepius, who were both associated with healing and bringing disease.

The epithet (1) broteri honours an outstanding Portuguese botanist, and one of the directors of the botanic garden in Coimbra, Félix de Avelar Brotero (1744-1828), who published the first detailed flora of Portugal at the beginning of the 19th century.

- Epithet : an adjective or phrase expressing a quality or attribute regarded as characteristic of the person or thing mentioned.

The plant P.broteri (before it was called this though) was attributed with mystical powers, such as warding off evil spirits, protecting crops, and attracting good fortune. It was also said to have the ability to soothe the soul’s pain. The Greeks and Romans used its seeds in rituals to combat nightmares and sorrows caused by magical creatures, such as fauns

P.broteri has documented uses in Iberian (1) folk medicine for conditions like epilepsy, gout, varicose veins, haemorrhoids, and arthritis, though its use is cautioned against due to potential severe side effects.. The toxicity of its fruits, seeds, and flowers makes it unsuitable for medicinal use, and scientific data on its efficacy and safety is limited compared to other Paeonia species, such as those used in Traditional Chinese Medicine.

- “Iberian” can refer to the ancient peoples and languages of the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal), the peninsula itself, or things related to the modern countries of Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar, and Andorra.

The toxicity of this plant (with which I have no experience as a herbalist – or a chef for that matter) is what diverts me from choosing it as an ingredient. Others will reference that it is poisonous to dogs and cats (but not humans) but will then also not recommend it be used medicinally in humans due to its “stong side effects” (1)

- this is not unusual in herbal medicine. Several strongly medicinal plants (foxglove (digitalis), squill, autumn crocus) are valuable medicinal plants but are restricted due to their toxicity and are VERY low dose plants (more than a few drops of the extract can prove to be toxic)

The website Mexico Desconocido publishes a recipe for atlaquetzalli that differs a little (florally speaking). They are also one of the few that mention “Initially, it was consumed fermented and had a rather sour taste”

Semillas de cacao

Vainilla

Chile

Hoja santa

Orejuela

Teonacaztle

Miel de abeja

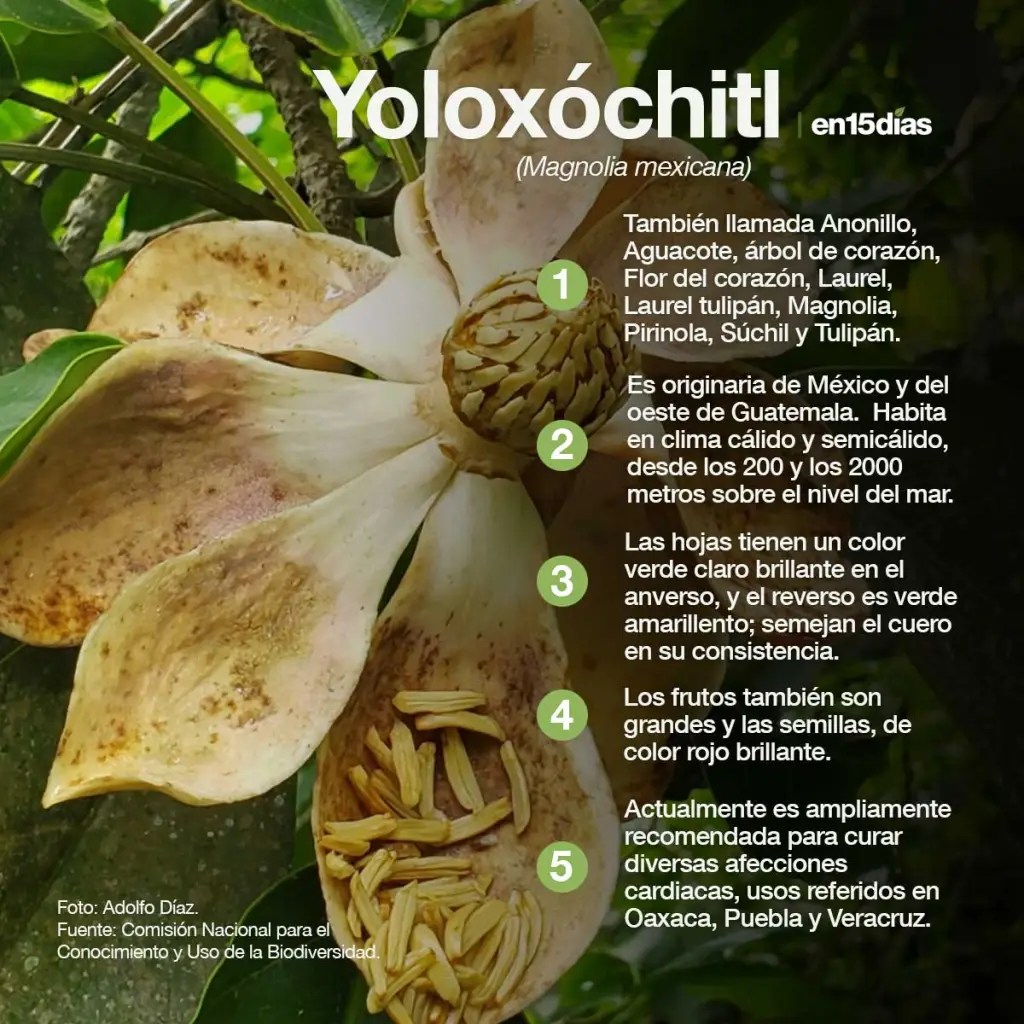

Flor de magnolia

Acuyol

Flor de magnolia (Magnolia mexicana previously Talauma mexicana) was known by the Aztecs as yolloxochitl or heart-flower (1).

- So named due to the (superficial) resemblance of the unopened flower buds to a human heart. I go into this in a little more detail in Xochipilli : Intoxicating Scent.

The flower was highly esteemed because of the sweet odour of the blossoms, with a single flower being sufficient to perfume a whole house. These flowers were reserved for the exclusive use of the nobility.

The plant was also valued also for its medicinal properties, and it still finds use in herbal medicine today. The main use of Magnolia mexicana in traditional Mexican herbal medicine was to cure heart diseases, and it is believed that it also cures emotional ailments such as sadness and nostalgia. For this reason, people call it “heart flower” (Martínez 1969). The bark is employed for fevers and is said also to have an effect upon the heart similar to that of digitalis (foxglove). Other diseases treated with the plant are diarrhoea, stomach pain, joint pain, epilepsy, nervousness (Elizondo-Salas et al. 2019), female infertility, menstrual problems, and gout (Waizel 2002).

A decoction of the flowers is administered for epilepsy, paralysis, and various heart affections, and as a tonic.

The seeds and carpels of the fruit are used, which are boiled in water to prepare a tea, which is recommended to drink while still hot, twice a day, in the morning and at night

Another query I have is with the ingredient “acuyol”. Now, acuyo is another name for Hoja Santa but, in the recipe above both Hoja Santa and acuyol are mentioned. I cannot find hide nor hair of an “acuyol”. It has been suggested that this spelling is a typo of acuyo but it is used very often (perhaps an issue of it being misspelled once and then forever after being referred to by this misspelling) and there is also the fact that it has been mentioned as well as Hoja Santa (1) so I am a little confused (but only too happy to have something else to research)

- Common names (en español) include Hoja santa, Yerba santa, Acuyo, Anisillo (which refers to the anise-like fragrance of these plants)

Curiel Monteagudo (2004) notes of atlaquetzalli,

The culinary craze for cinnamon and sugar extinguished the pre-Hispanic flavours of some dishes and of atlaquetzalli, the precious water or cacao drink, formerly flavoured with pixtle, tilxochitl, cacaloxochitl, mecatlxochitl, xocoxochitl, hueynacaztle, and honey.

El furor culinario por la canela y el azúcar extinguen los sabores prehispánicos de algunos platos y del atlaquetzalli, el agua preciosa o bebida de cacao, antiguamente condimentada con pixtle, tilxóchitl, cacaloxóchitl, mecatlxóchitl, xocoxochitl, hueynacaztle y miel.

- Pixtle – hueso de mamey (the mamey seed). See Pixtle. The Mamey Seed. for more information

- tilxochitl – a spelling error? tlilxochitl is the Nahuatl name for the vanilla orchid (Vanilla planifolia)

- cacaloxochitl – (also known as cacaloxuchitl) is a Nahuatl name for a type of frangipani, specifically likely Plumeria rubra. See Xochipilli : Intoxicating Scent. for more information.

- mecatlxochitl – it has an intense aroma, and is also medicinal. (1)

- xocoxochitl – Xocoxochitl is the Indigenous Nahuatl name for the plant Pimenta dioica, a tree native to Mexico that produces the spice known in English as allspice or sometimes as “Tabasco pepper” by the Spanish (as it was native to the province of Tabasco in New Spain)

- Hueynacaztle – “Uei nacaztli” refers to Cymbopetalum penduliflorum (our pre-cinnamon cinnamon flavouring

- and honey (miel de abeja)

- Hay otra que se llama mecatlzochitl, hácese en tierras calientes, es como hilos torcidos: tiene el olor intenso, tambien es medicinal. Hay otra que se llama ayauhtona, es verde clara, tiene las hojas anchuelas, redondillas y con muchas ramas, y en todas hace flores, es de comer. There’s another one called mecatlzochitl, made in warm soils, like twisted threads; it has an intense scent and is also medicinal. There’s another one called ayauhtona, which is light green, has wide, round, and multi-branched leaves, and all of them bear flowers; it’s edible. Interestingly this definition brings up another strongly scented herb – ayauhtona – which I have investigated previously (and might be a variety of Porophyllum – the very reason I started this Blog in the first place. Check it out Ayauhtona. Another Poreleaf?

Mecatlxochitl

Hay una yerba que’ se llama аxосорасопi, hácese en las montañas, es muy olorosa, y tiene intenso olor. Hay otra olorosa que se llama quauhxiuhtic, es muy tierna echada en la agua, toma su olor, y bebiendola dá mucho sabor y contento. Hay otra que se llama mecatlxochitl, hácese en tierras calientes, es como hilos torcidos: tiene el olor intenso, tambien es medicinal. Hay otra que se llama ayauhtona, es verde clara, tiene las hojas anchuelas, redondillas y con muchas ramas, y en todas hace flores, es de comer. Hay otra que se llama tlalpoiomatli, esta yer

There is a herb called axosorasopí, grown in the mountains, very fragrant, and with an intense aroma. There is another fragrant herb called quauhxiuhtic, very tender when placed in water; it takes on its aroma, and drinking it gives great flavor and pleasure. There is another herb called mecatlxochitl, grown in warmer lands, is like twisted threads: it has an intense aroma, and is also medicinal. There is another herb called ayauhtona, which is light green, has wide, round leaves with many branches, and all of them produce flowers, and is suitable for food. There is another herb called tlalpoiomatli, this herb-

(unfortunately this is the last page on the pdf and it cuts off mid sentence. I did find the rest in another extended version of the text – See References)

-ba tiene las hojas cenicientas, blandas y vellosas*hacense en ella flores; por su olor, hacen de ellaperfumes para meter en los cañutos del humo, y difunde su olor

So it finished up as…

There is another called tlalpoiomatli; this herb has ashy, soft, and hairy leaves; flowers are made from it; because of its aroma, it is used to make perfumes to put in smoke tubes, and it diffuses its scent.

Creation myth of atlaquetzalli

Legend tells that Quetzalcoatl stole a cacao tree from the paradise of the gods and planted it in Tula; he then asked Tlaloc to send rain to the earth so the plant would grow. The god asked Xochiquetzal to give the plant some beautiful flowers. The cacao tree bore fruit, and Quetzalcoatl sorted and cleaned the pods; he extracted the seeds to ferment, let them dry, and then roasted them. The women of the city ground the dried product. Finally, Quetzalcoatl extracted a liquor and taught them how to prepare a drink of the gods: atlaquetzalli. This beverage was consumed in Tenochtitlan and Teotihuacán.

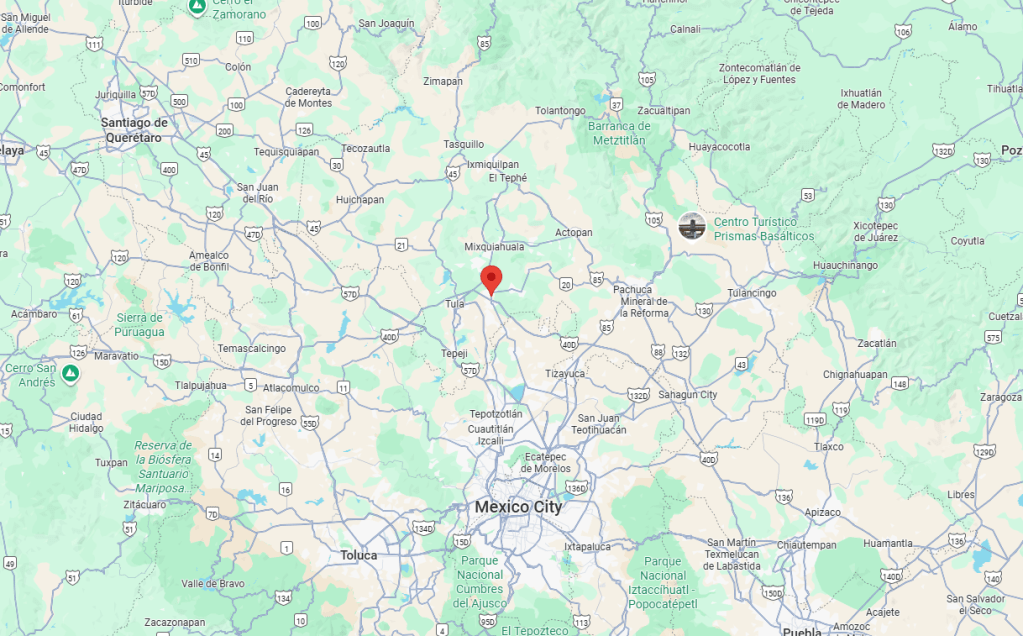

Atlaquetzalli is said to originate from Tula (a municipality in the state of Hidalgo).

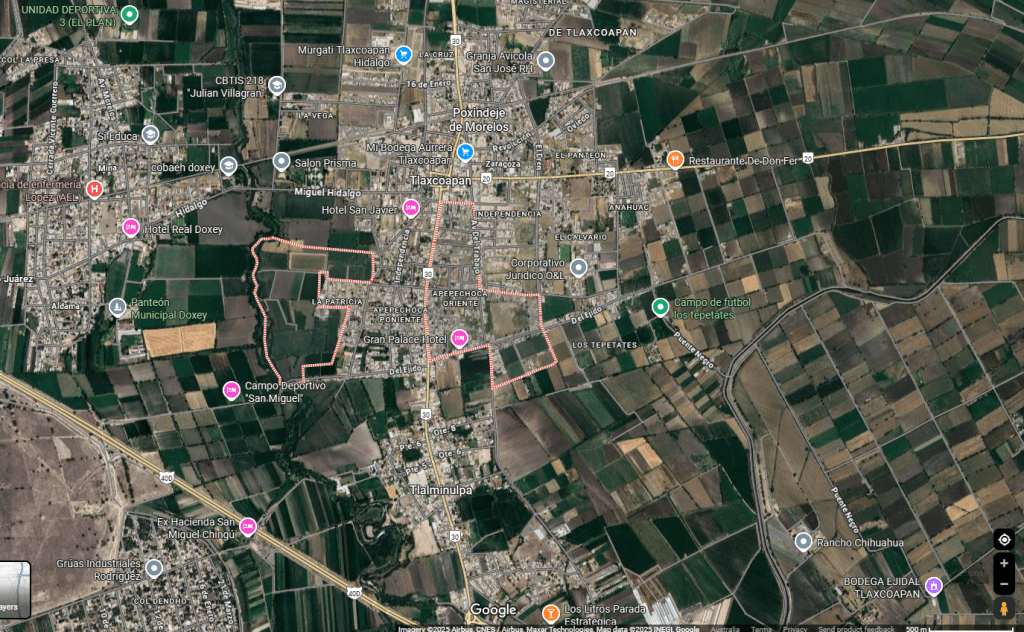

Doxey, Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo

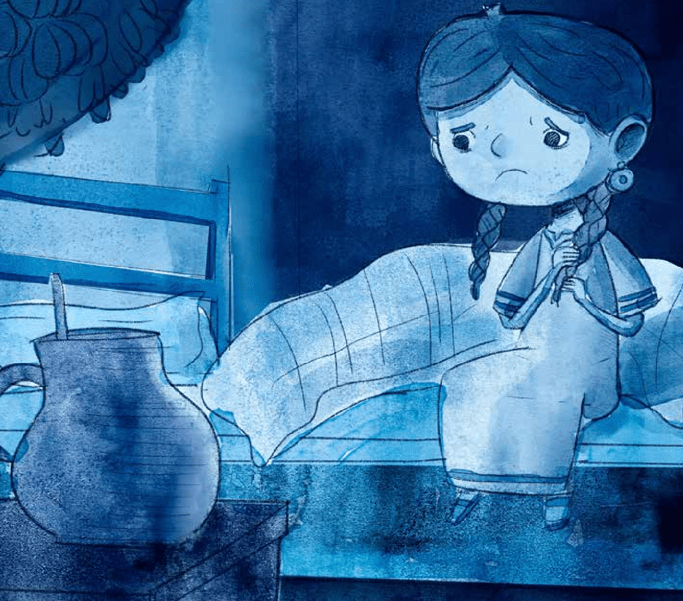

Mexico’s National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI) has published the short story: Atlaquetzalli, “She Who Prepares Precious Water,” written by Karen Lisset and Marco Antonio Hernández Hernández.

The grandparents say that this story was found inside a clay pot with seven cocoa beans by master masons, while they were opening the gutters for the perimeter wall of the Tula refinery, in the community of Doxey in Tlaxcoapan, Hidalgo”.

This story differs from the legend above in that the drink was created by a young girl.

This story also mentions that the drink was fermented. Most other explanations seem to miss this step.

Mayahuel (yes that Goddess) was visiting the great Tollan of the lands of Topilzin Quetzalcóatl. Quetzalcóatl sent his tlamemes (1) to inform all the calpulli (2) of the great Teotlalpan about the important visit, and to inform his people to prepare foods that would “conquer the palate of Mayahuel”.

- A tlameme (from the Nahuatl tlamama, “to carry a load”) was a Mesoamerican porter, particularly common in the Aztec Empire, who carried goods and sometimes people on their backs using a frame called a cacaxtli and a head strap known as a mecapal.

- A calpulli was a fundamental sociopolitical unit of the ancient Aztec (Mexica) society, functioning as a neighbourhood, clan, or cooperative group bound by kinship, communal land ownership, and shared labor for common good. The term, meaning “great house” or “group of houses” in Nahuatl, describes a territorial and organizational division below the level of a city-state (altepetl). Calpulli were responsible for distributing land, collecting tribute, and providing a shared infrastructure, including a temple and market.

A young girl (called Mahetsi in this story) from the calpulli of Apepechoca was excited as her father had just returned home from working and had with him 20 cacao beans (which represented a small fortune). Her tata (father) was going to gift these beans to Tlaloc.

Mahetsi’s grandmother had taught her to cook from a very young age and grandma had in fact worked as a cook in the Place of Tollan in her youth. Her father did not gift all the cacao beans to Tlaloc but gave thirteen if them to his daughter to prepare a dish for Mayahuel. This was surprising and exciting as these beans are “more precious than the gold that hangs from the chest of our lord Quetzalcoatl.”

First she took the beans and toasted them on the comal. She then crushed them gently in her molcajete, cleaned the skins from them and then ground them to a fine amber coloured powder on the metate. This powder was placed into a gourd with some water and allowed to soak overnight. The next morning this paste was blended into boiling water with a chicoli (1) but she was distraught as the drink only had a mild aroma and was very bitter. Her grandmother gave her some honey for the mix.

- The forerunner to todays molinillo – Mexican Cooking Equipment : The Molinillo

She checked the drink again the next morning before setting out for the Palace but noted that nothing had changed except a thin whitish foam had appeared on the liquid. She was upset that she would have nothing worthy to offer Mayahuel.

After arriving at Tollan (and being the last to be led into the Palace) she was amongst cooks who brought fine and exotic foods from all over the region. This worried her all the more. This worry was further compounded by stories of the other cooks who were saying that nothing being served was pleasing to Mayahuel.

Nevertheless Mama didn’t raise no quitter so she boiled her drink one final time and poured it from one container to another to aerate it and “at that moment, a delicious aroma began to emerge from my cocoa drink, a fresh breeze passed by carrying the aroma to the main room of the palace where the sovereigns lay in state”

She then heard the voice of Master Quetzalcoatl who politely asked Mayahuel to know where that smell was coming from, and with a sweet but firm voice he invited her to come in and offer the drink. She first served Quetzalcoatl who was so taken by the drink he served it immediately to Mayahuel.

Mayahuel, without hesitation exclaimed that it was the aroma of the gods and drank it. She asked Topiltzin what the name of this exquisite drink was and he responded with Xocolatl. Mahetsi’s offering was a great success and she returned home (in disbelief over what had just occurred) to a very proud family.

One morning, several days later, messengers from Tollan arrived to inform her family that, by decision of Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl (1), she had to present herself immediately before the Tlamachtiani (2) of the palace, to begin her studies in the Calmecac and learn from the sacred books and Toltec teachings.

- Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl literally means One Reed, Our Prince Plumed Serpent,

- Tlamachtiani is a word from the Nahuatl language that translates to “teacher” or “master”. It can be used to refer to both male and female educators

Mahetsi left her calpulli to become an Atla-quetzalli, “she who prepares precious water.”

Atlaquetzalli today

Fernando Rodriguez Delgado runs Chocolateria Macondo in Teotihuacan. His fascination with Mexico’s history (and chocolate) was piqued by the recipes printed in Sahaguns codex and his interest in finding the ingredient mecaxochitl.

Definitely worthy of a Tlatoani.

If you’re ever in Teotihuacan then drop by at Adolfo López Mateos 3, Teotihuacán Centro, San Juan Teotihuacán de Arista, Estado de México and drink yourself a cup of the nectar of the gods.

References

- Adame J, Adame H. Plantas Curativas del Noreste Mexicano. Monterrey, México: Ediciones Castillo; 2000; p. 101.

- Argueta A. Atlas de las Plantas de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana Vol.2. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional Indigenista; 1994; pp. 644-645.

- Argueta A, Zolla C. Plantas Medicinales de Uso Tradicional en la Ciudad de México. México, D.F.: UNAM; 2014; pp. 63-64.

- Berdonces J L. Gran Diccionario de las Plantas Medicinales. Barcelona, Spain: Editorial Océano; 2009; pp. 489-490.

- Brinton, Daniel Garrison, (1887) Ancient Nahuatl poetry, containing the Nahuatl text of XXVII ancient Mexican poems

- Curiel Monteagudo, José Luis (2004) Construcción y Evolución del Mole Virreinal (Construction and Evolution of Viceroyal Mole) Patrimonio Cultural y Turismo. Cuadernos 12; El mole en la ruta de los dioses. 6o Congreso sobre Patrimonio Gastronómico y Turísmo Cultural (Puebla 2004). Memorias; CONACULTA ISSN: 1665-4617

- De la Cruz-Cabanillas, Isabel. (2022). Chocolate or an Indian Drinke. Kwartalnik Neofilologiczny. 3-2022. 10.24425/kn.2022.142973.

- Elizondo-Salas AC, Sánchez-Cuahua R, Jimeno-Sevilla HD, Ixtacua-Rosales E, Clemente-Genoveva B. (2019) Traditional knowledge and use of fruits of yoloxóchitl (Magnolia mexicana DC)by nahua communities in the Sierra of Zongolica, Veracruz, México. Memoirs NeotropicalMagnolia Conservation Consortium; 2019

- Etkin, Nina. L. (2000) Eating on the Wild Side: The Pharmacologic, Ecologic and Social Implications of Using Noncultigens

- Gonzalez Stuart, Armando. Little Hand Flower : UTEP Herbal Safety – https://www.utep.edu/herbal-safety/herbal-facts/herbal%20facts%20sheet/little-hand-flower%20.html

- Hellmuth, Nicholas M.; (2014) Maya Ethnobotany (Complete Inventory) Fruits, nuts, root crops, grains, construction materials, utilitarian uses, sacred plants, sacred flowers. FLAAR Report Thirteenth edition, May 2014 – https://www.maya-ethnobotany.org/FLAAR-Reports-Mayan-ethnobotany-Iconography-epigraphy-publications-books-articles-PowerPoint-presentations-course/26_Mayan-ethnobotany-Guatemala-Honduras-El-Salvador-Mexico-Belize-utilitarian-and-sacred-plants-flowers-annual-report-J-2014.pdf

- Jimeno, David & Elizondo-Salas, A. Carolina. (2022). Magnolia mexicana DC. Ethnobotanical monograph.

- Jiménez A. Herbolaria mexicana 2a ed. Madrid: Mundi-Prensa; 2012; p. 193.

- Johnson T. CRC Ethnobotany Desk Reference. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1999; p. 196.

- Journal of Ethnobiology (1983) published by the Center for Western Studies (Flagstaff, Arizona), volume 3 (1983)

- Keoke, Emory Dean & Kay Marie Porterfield, Kay Marie (2002) Encyclopedia of American Indian Contributions to the World (2002), page 118:

- Linares E, Bye R, Flores B. Plantas Medicinales de México-Usos y Remedios Tradicionales. México, D.F.: Jardín Botánico UNAM; 1999; pp. 56-57

- Lopez Austin, A. 1974. Dcscripcion de med icinas en tcxtos dispcrsos del Libro XI de los Codices Matritense y Florentino. In: Leon -Portilla , M. (Ed.), Estudios de Cultura Nahuatl 11. Mexico City: Universidad

- Mabberley D. Mabberley’s Plant Book 3rd ed. London: Cambridge University Press; 2008; p.180 .

- Martínez M. (1969) Las plantas medicinales de México. México: Ediciones Botas.

- Mecatlxochitl – Untitled work : Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León – http://cdigital.dgb.uanl.mx/la/1080012524_C/1080012525_T3/1080012525_29.pdf – which I believe to de a scan of Historia general de las cosas de Nueva Espaa, : que en doce libros y dos volumenes escribi, – https://ia800400.us.archive.org/17/items/historiagenerald03saha/historiagenerald03saha.pdf

- Mendoza-Castelán G, Lugo-Pérez R. Plantas Medicinales en los Mercados de México. Chapingo, Estado de México: Universidad Autónoma Chapingo; 2011; pp. 390-391.

- Muñoz Zurita, R. ” Ear Flower . ” Encyclopedic Dictionary of Mexican Gastronomy . Larousse Cocina

- Pereira, J., & Teixeira, G. (2022). Pharmacognostic Survey on Paeonia Broteri – An Iberian Endemism. RA Journal of Applied Research, 8(12), 897–902. https://doi.org/10.47191/rajar/v8i12.09

- Quattrocchi, U. World Dictionary of Medicinal and Poisonous Plants (Vol. 2). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012; p. 227.

- Relaciones Geograficas. 1982. Relaciones Geograficas del Siglo XVI: Guatemala . Mexico City : Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico

- Sahagun, B. de 1956. Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva Espana. Mexico City: Editorial Porrua

- Standley P.C. (1926) Trees and Shrubs of Mexico. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Vol 23 Smithsonian Institution; Washington

- Szoblik, Katarzyna. (2019). Female Roles in the Religious Rituals and Political Performances among the pre-Colonial and Colonial Nahua. Mitologías hoy. 19. 309. 10.5565/rev/mitologias.517.

- Tezozomoc, H.A. 1975.CronicaMexicana.MexicoCity: Editorial Porrua

- Waizel BJ. (2002) Uso tradicional e investigación científica de Talauma mexicana. Rev Mex Car.2002;13(1):31–8.

- “Xocoxochitl.” The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Malcolm Eden. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2007. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0000.791 (accessed [fill in today’s date in the form April 18, 2009 and remove square brackets]). Originally published as “Xocoxochitl,” Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, 17:656 (Paris, 1765).

Websites

- Ahuiani via micorazonmexica on Instagram https://www.instagram.com/p/C0E2t3egyqa/?img_index=6

- atl – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/atl

- atlaquetzalli. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/atlaquetzalli

- Chiranthodendron pentadactylon (Mexican hand tree) — at the San Francisco Botanical Garden – By Stan Shebs, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=693628

- Chiranthodendron pentadactylon Open f lower showing nectary and abundant nectar. – By Jared Dubberlin – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=139476792

- Edible Flowers in the Mayan Diet : Cymbopetalum penduliflorum – https://www.revuemag.com/edible-flowers-in-the-mayan-diet/

- http://dspace.uvaq.edu.mx:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/761/Texto_completo.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- https://www.maya-ethnobotany.org/FLAAR-Reports-Mayan-ethnobotany-Iconography-epigraphy-publications-books-articles-PowerPoint-presentations-course/1_Mayan-ethnobotany-iconography-plants-food-fruits-sacred-flowers-trees-Guatemala_FLAAR-annual-report-2010-2011.pdf

- https://www.mercasa.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/18Chocolate.pdf

- Origin myth – https://www.milenio.com/cultura/atlaquetzalli-bebida-de-cacao-prehispanica-de-hidalgo

- Origin myth – https://lasillarota.com/hidalgo/vida/2021/11/17/atlaquetzalli-una-bebida-del-hidalgo-prehispanico-305004.html

- Pimentinha Branca da Mata (White Pepper of the Forest (Piper amalago) Images by Gustavo Giacon https://ciprest.blogspot.com/2019/11/pimentinha-branca-da-mata-piper-amalago.html

- Quetzalli – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/quetzalli

- Quetzalli – https://archive.org/details/ancientnahuatlpo00brinrich/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater

- Rosa1 – https://parqueculturalsierradegata.es/experiencia/rosa-de-alejandria-y-yacimiento-arqueologico/

- Rosa2 – https://www.agromatica.es/rosa-de-alejandria/

- teonacaztli. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/teonacaztli