The practice of curanderismo is the living cultural tradition of holistic healing practices of the peoples of “Latin” America. Although variations of this tradition exist within most of the Americas my focus is on the traditions of Mexico and the south-western United States of America.

Curanderismo is a holistic healing system that treats the whole person—body, mind, and spirit—using a blend of herbs, rituals, and remedies to address physical, emotional, and spiritual ailments. It recognizes that illness can arise from strong emotions, imbalances with one’s environment, spiritual forces, or even moral transgressions and recognises and treats ailments that have no real equivalent in modern medical practices.

The traditions of these healing practices date back to a time before the Aztec but it has adopted and adapted other philosophies and practices from European and African traditions (as well as a multitude of Mesoamerican cultures).

Gonzalez-Swafford & Gutierrez (1983) note that “Physical illness is generally considered to be due to an imbalance in the body between hot and cold” and that “This hot-cold theory of disease causation is very old” (1) with the classification being derived from “ancient Greek humoral pathology” (2) which has been “adapted and practiced by the Mexican-American culture” (3)

- Which is certainly correct

- This part is not so much correct as the indigenous medical practices already had a hot-cold theory in practice. This theory not only applied to the human body (with regards to both physical and psychological illness) but to balance within the whole universe itself.

- Also correct (but I think less correct the further you venture towards the heart of Mexican indigenous cultures)

Smith (2003) notes that “Traditional medicine in Mexico is based on the Greek belief, brought by the Spaniards, in the four humors: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile” and that “These beliefs were brought over by the Spanish during colonization” (1). She does go on further to say that “over the years (these practices) combined with some of the already existing ones to form a belief, which is based on a balance between hot and cold.” (2)

- This classification of humors certainly would have been introduced by the Spaniards

- This at least acknowledges the pre-existing indigenous theories/philosophies/practices

Many of these practices are considered (at the very least) “quaint” by modern medical practitioners but more often than not they are considered ignorant and backward by university trained doctors (2). One of these practices is the treatment of various digestive disturbances that fall into the category of empacho (1).

- See Empacho for more detail on this.

- and are even listed in texts on psychiatric illnesses (more on this later)

Tripa ida is an offshoot of empacho and can be considered a potentially more dangerous form of digestive disturbance.

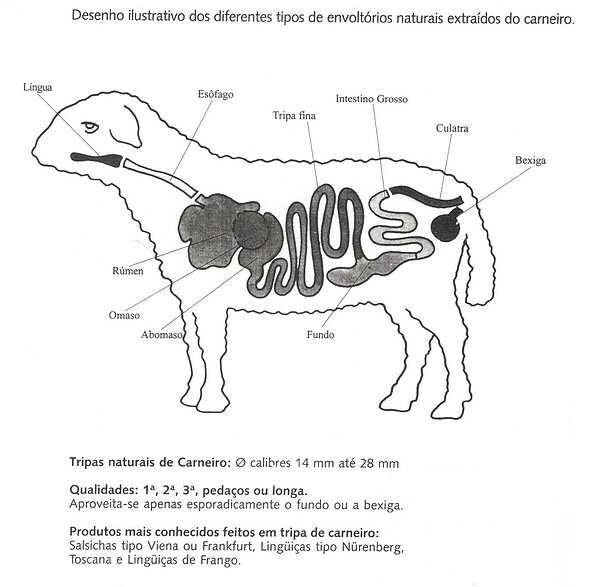

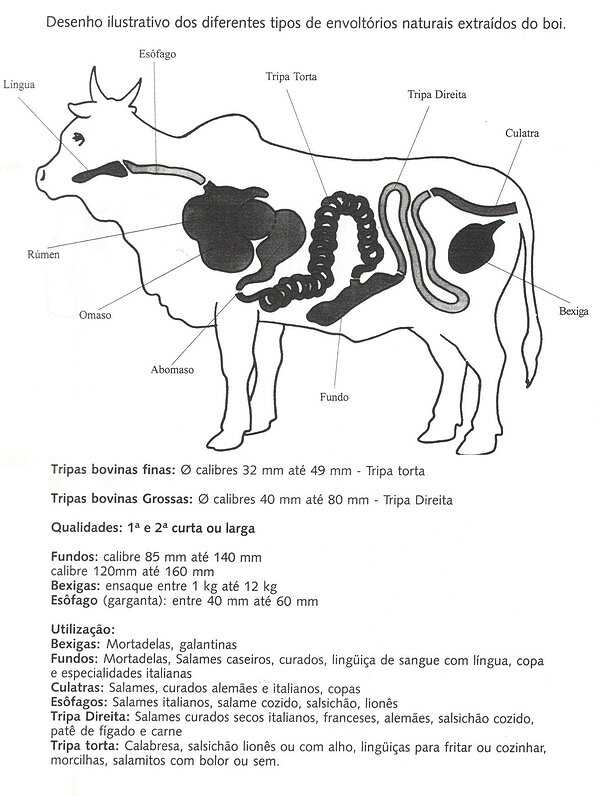

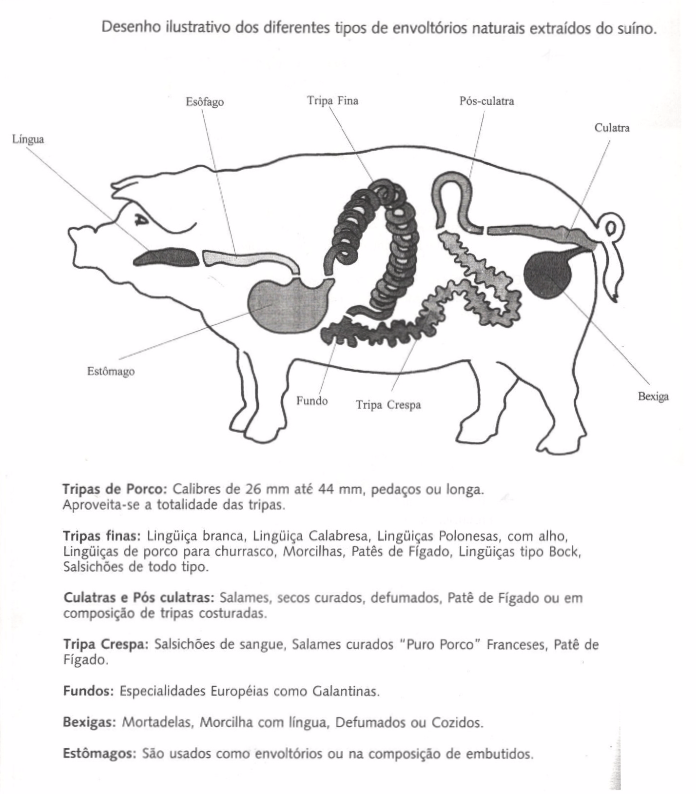

But first. Tripe (tripa en español) is a form of offal (1) typically defined as “a type of edible lining from the stomachs of various farm animals”, usually from sheep and cattle but also includes the pig.

- Offal refers to the internal organs and non-carcass parts of an animal that are edible, such as the liver, kidneys, heart, tongue, and intestines.

It is also used for tacos (but that is not why we’re here today)

According to the Diccionario Enciclopédico de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana, Tripa ida is……

También tripa. Sinónimo(s): se va la tripa (1), se sube la tripa (2).

Also Tripa. Synonym(s): (1) gut goes away (the gut is going away), (2) gut goes up (the stomach rises).

“Tripa ida” literally translates to “the gut is gone” or “the gut has gone bad” in Spanish. It does not directly refer to the same condition as empacho. It signifies a severe digestive problem, potentially indicating a serious or critical state of the digestive system.

Empacho is often defined as a “cultural term” (1) (rather a medical one) used in Latin American cultures to describe a digestive issue where (at its most basic definition) food is believed to be “stuck” in the gastrointestinal tract. While Western medicine classifies empacho symptoms as indigestion (dyspepsia).

- or a “culture bound syndrome” or “culture specific syndrome” and often a “folk illness”(2)

- a recognized set of symptoms (including psychological and physical ones) within a particular society or culture that may not be understood or recognized by a different cultural group or the mainstream biomedical system. These illnesses often have unique explanations for their causes, symptoms, and appropriate treatments that differ from conventional medicine (this does not make them any less relevant though)

Huxtable (1998) differentiates between empacho (1) and tripa ida (2) with one being caused by infection and the other having no particular causation noted but only the resulting effect of the condition.

- Infection caused by undigested food adhering to the gastrointestinal tract

- “locked” intestines

Kay (1977) in her “Southwestern Medical Dictionary ” notes of tripa ida is that it is a condition of the “Intestines locked by fright” which certainly links it to the conditions of susto and espanto (a potentially more dangerous form of “fright sickness” than susto) but, again, not the same thing as susto itself.

The Oxford dictionary definition (I believe) gets the definition wrong by noting that tripa ida is “Another name for susto. [From Spanish tripa intestine (believed in the past to be the seat of the soul) + ida departure]” maybe they procured their information from the DSM-5

The Diccionario Enciclopédico de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana notes that tripa ida is “a digestive disorder related to diarrhoea, due to a supposed organic disorder of the intestines” which the Mayos of Sinaloa (1) “commonly attributed to susto” (2) and has higher incidence in children. They also note that it can “originate from exertion, which causes the gut to twist; or when, due to lack of food, air enters and accumulates in sacs, “swallowing” it, and impedes the normal passage of food. This form of obstruction distinguishes this condition from indigestion and latido” (3). Tripa ida manifests itself with tiredness, weakness, pain in various parts of the body (especially in the abdominal region), diarrhoea, vomiting and fever.

- The Mayo people are an indigenous group primarily from the southern Sonora and northern Sinaloa regions of Mexico, living along the Mayo and Fuerte rivers. Also known as the Yoreme

- But is not susto itself. For a little more on susto see Glossary of Terms used in Herbal Medicine.

- Latido – a condition identified by a palpitation in the pit of the stomach (epigastrium) or at the level of the navel (mesogastrium), the etiology of which is generally related to eating problems. The fundamental manifestation to establish the diagnosis is the presence of a “beat”, “jump”, “pulsation” or “palpitation” in the abdominal region, at the level of the navel or mouth of the stomach. In addition to this, loss of appetite is frequently reported, stomach pain, hardening of the belly, weight loss, weakness, vomiting, diarrhea, headache and, occasionally, “tremors”, cold sweat, febrícula (a slight, short-lived fever, often with no apparent cause) or fiebre (fever). La febricula (a low-grade fever) is a moderate elevation of body temperature, usually between 37°C and 38°C, while a fever is considered a temperature above 38°C.

Gonzalez-Swafford & Gutierrez (1983) place tripa ida in the classification of serious illnesses (1) and to be a condition in which the family will seek medical intervention of some variety (rather than treating the illness at home with their own remedies)

- along with latido (cachexia – a severe wasting syndrome of lean body mass, including muscle and fat, that cannot be reversed by increasing calorie intake alone) and pujo (grunting and straining associated with constipation – although I have never come across this term before)

In the DSM-5 (1) Tripa ida (2) is incorrectly categorised as susto (3) although it does list stomachache, and diarrhea (sic) as “Somatic symptoms (4) accompanying susto” which are symptoms typically associated with empacho. In short they denigrate these illnesses (and the practices accompanying them) as mental illnesses.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illnesses is the latest edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s professional reference book on mental health and brain-related conditions. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has faced controversies primarily related to its DSM-5 revision, centering on the false positives problem of pathologizing normal human distress. Other major criticisms include allegations of secrecy and conflicts of interest, potential cultural bias, the “medicalization of normality,” a lack of consistent reliability and validity for some diagnoses, and concerns about the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on diagnostic criteria.

- listed alongside Susto, espanto, pasmo, perdida del alma, or chibih

- “An illness attributed to a frightening event that causes the soul to leave the body and results in unhappiness and sickness.”

- The word “somatic” means relating to or affecting the body, particularly the physical body as distinct from the mind or spirit.

Now I have to admit that I have only recently encountered the term “tripa ida” so a lot more research (1) and personal experience is required before I can claim any expertise on the subject but the claims of tripa ida being understood in the context of susto as “departed soul,” because the Aztecs (or Mesoamerican peoples in general) believed the intestines to be the “seat of the soul” doesn’t gel with me.

- I’ve gone through all my books (and I have many) on curanderismo and herbalism and healing practices of Mexico and the SW United States and found no mention of the condition. It also never came up during my studies of curanderismo with the University of New Mexico (Albuquerque)

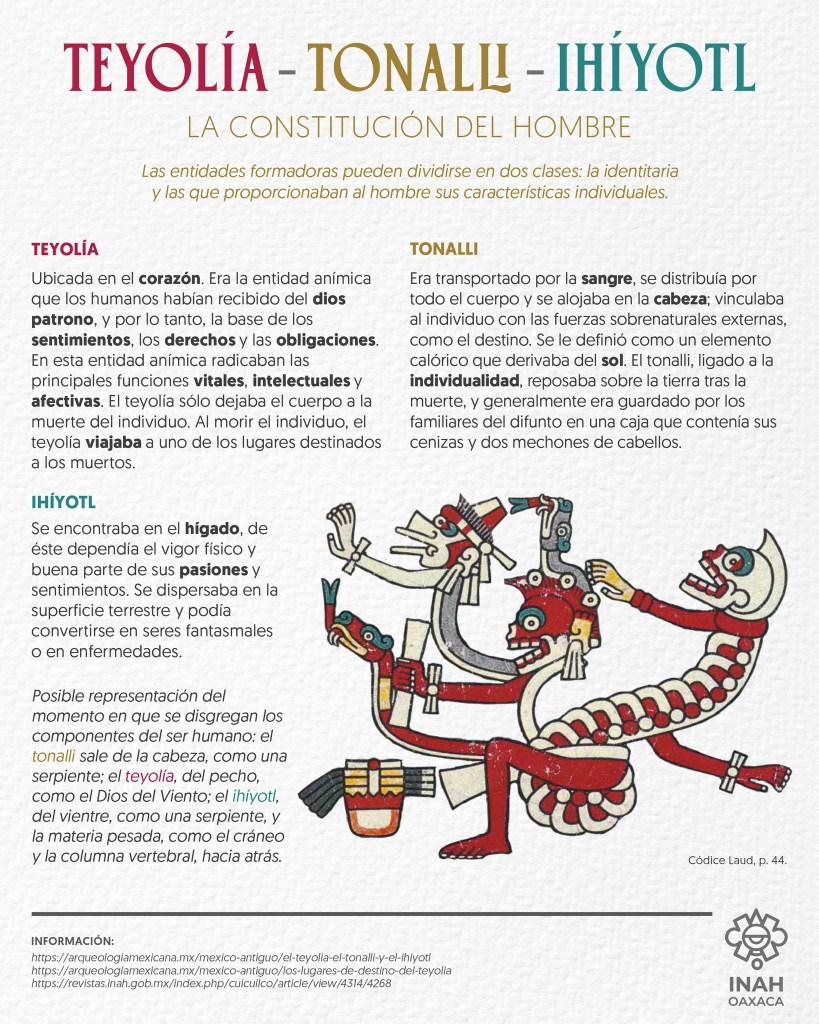

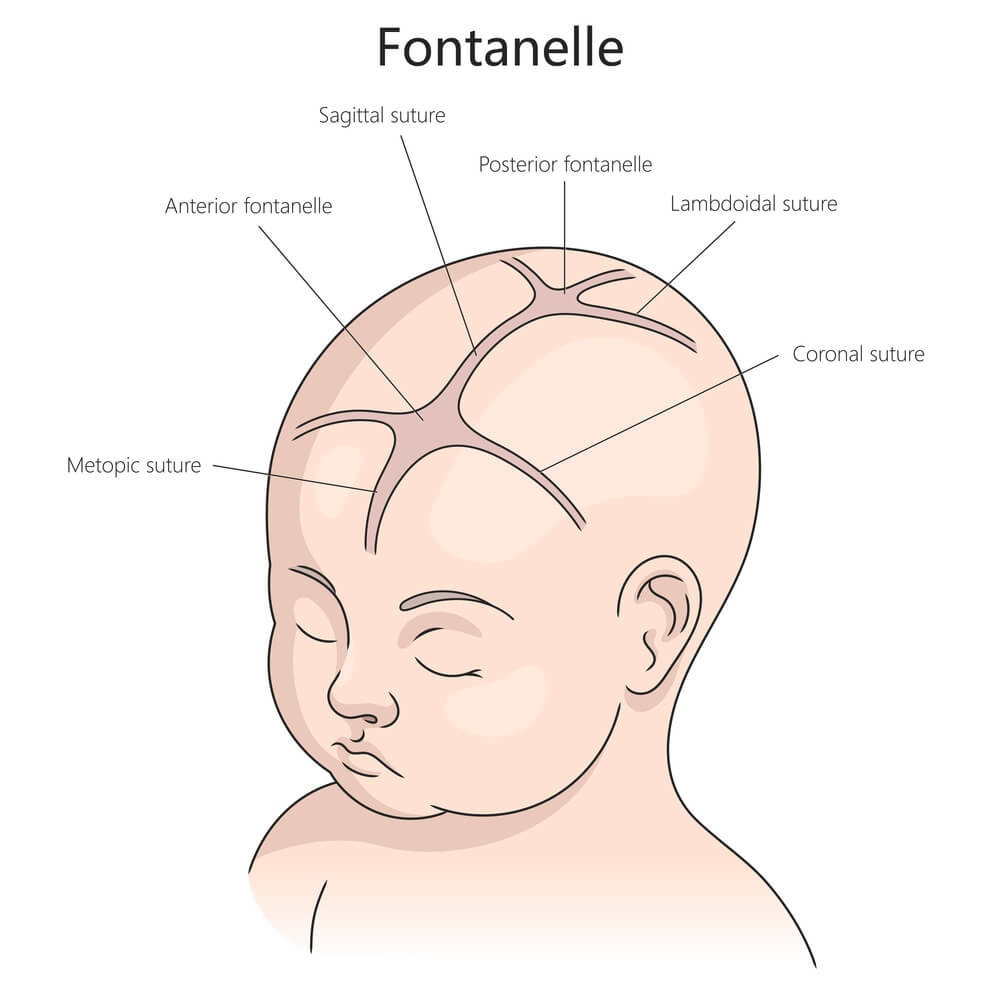

The Nahua people of Mesoamerica believed that the soul comprised three entities: Tonalli, Teyolía, and Ihíyotl, three souls in the body (1). Tonalli is located in fontanelle area of the skull. Teyolía is located in the heart and Ihíyotl is in the liver. Each of these souls has its own functions and protective deities.

- See A Short Discourse on the Aztec Soul. for a little more on this

Tonalli is located in fontanel area of the skull.

“The tonalli was a sort of soul, located in the crown of the head, that regulated body temperature and growth and played a major role in determining a person’s character and fate. Montoya Briones (1964) notes that in the northern Sierra de Puebla, the inhabitants believe this is the soul that travels while you sleep at night, and then comes back. This is the soul that leaves and comes back every time you sneeze (1), or whenever you yawn, or even when you are startled. The Nahua believed that it was not good to sneeze and keep talking, because it causes your tonalli to leave and once your Tonalli leaves, you have to wait for a period of time before it returns. At that moment, anything can enter your body. Tonalli loss resulted in illness and, if healing ceremonies were not performed, death. (Burkhart 1996)

- this is also the reason we say “bless you” when someone sneezes as (an old) belief was that a sneeze could expel a person’s soul from the body. Saying “bless you” was thought to prevent evil spirits (or the Devil himself) from seizing the released soul and to protect the body from evil entering during the moment the soul was believed to be absent.

The tonalli differs from the other two souls, the soul of the heart (Teyolía) and the soul of the liver (Ihiíyotl) which only leave your body when you die; those two souls will exit only at the exact moment of your death

Teyolía is located in the heart

teyolia. – Principal English Translation: one of the two basic spiritual components of the human being, located in the heart, conceived as the centre of vital force and conscience (1)

Literally, the teyolia, or “someone’s animator” was “commonly identified in the sixteenth-century with ‘the soul’. There was a good reason for this: it was considered by the Nahuas to be part of the self that survived mortal life, and, unlike the unstable tonalli (1), it was the vivifying force part excellence, that could never abandon the living being.” As something centred in the heart, “it shared with it its qualities of cognition, sentimentality, and desire. But like the heart, the teyolia was susceptible to those diseases that originated with illicit sexual acts or excesses, which were said to compress or darken the heart, or that were caused by sorcerers who magically devoured or ‘twisted’ hearts.”

- which was always subject to being scared off, by a sudden fright or other disturbing experience,

Now the closest we get to the intestines is the soul called Ihíyotl

Ihíyotl is in the liver.

Ihiyotl’ (breath) controlled an individual’s emotions, desires and passions. Of the three forces, ihiyotl is the most mysterious. Perhaps its mystery stems from a lack of ethnohistoric descriptions of its significance and functions, but ihiyotl seems to have been visualized as “a luminous gas that had qualities of influencing other beings, in particular attracting them toward the person” (López Austin 1988)

ihiyotl.

Principal English Translation: breath, respiration; life; sustenance, blown air, a puff of air, a blast of air.

Ihiyotl was also linked to the breath expelled during speech

ihiyotl tlatolli, “breath + words = fine speech;”

Ihiyo, itlatol = His breath, his words.

“This was said only about the words of kings. They said ‘The king’s venerable breath, his venerable words.’ It was not said about anyone else’s words, only ‘the illustrious breath, the illustrious words of our lord.'” (Sullivan & Knab 1994)

As the nucleus of vigour, passions, and feelings, the ihiyotl was the soul that produced appetites, desires, greed, lust, and courage. Parts of this soul could leave the body as emissions expressing vigour, moderating pain, or inflaming courage. During sleep, for example, shamans could send their ihíyotl to invade other beings.

The proper functioning of the ihíyotl depended on the maintenance of good relations with other souls, a life of controlled emotions, and sexual balance. Excesses and sexual sins damaged it, leading to emissions that would seriously harm family, neighbours, crops, and other aspects of an individual’s life.

Death was considered the payment due to the gods for donating the materials necessary for human life. Death meant the disintegration of the human being as the parts that had formed the whole began to fall apart. Every part of the human being would follow the path of his or her particular destiny. The ihiyotl, for example, would wander the earth as a fearsome yohualehécatl, or “night air.”

This is just to point out that I’m wondering how it can be claimed that the intestines are the seat of the soul when nothing in Aztec philosophy seems to indicate this at all.

Treatment protocols for tripa ida

Research conducted in Los Mochis, Sinaloa by Thlahui Educa (1) presents information and treatment protocols for tripa ida. Interviews conducted with two sobadoras (2) offer insight into this condition.

- An educational community dedicated to the professional study of traditional and alternative medicines, indigenous languages, and cultures founded in 1974 and began by teaching the first course in parallel medicine at the Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Autónoma (Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University) of the State of Mexico; and in 1975, the Natural Medicine course at the IMSS Hospital Clinic in Toluca, State of Mexico

- Doña María Ángela Villegas Rivera and Doña Silvina Arellanes, both from Los Mochis, Sinaloa, practitioners of sobada – a traditional Central and South American form of therapeutic bodywork, often a massage, that involves manipulating soft tissues to address musculoskeletal, digestive, and reproductive health issues, with a particular focus on aligning the womb and pelvic organs.

La sobada de tripa (roughly Tripe massage} is a method for treating inflammation of the large intestine. Those who perform it say that it occurs when a person suffers a strong impression or a fright (1). Tripe massage consists of “unwinding the nerves and the tripe (large intestine)” (2)

- impresión fuerte o un susto

- desencoger los nervios y la tripa (intestino grueso)

This massage technique has been performed since ancient times in the northern part of the state. Those in charge of performing it must be highly trained and must have a very clear knowledge of the causes, symptoms, and treatment performed for the benefit of the patient. The massagers and believers of this technique say that the large intestine becomes inflamed due to “nervous problems, frights, strong impressions, anger, stress, depression” (1). The massage process (on the stomach, back, arms and calves) is very similar to the massage taught to me during my clinic training in naturopathy (quite similar to what I know as Swedish massage which is a fairly gentle form of massage that is not meant to cause any pain from its application).

- problemas nerviosos, sustos, impresiones fuertes, corajes, estrés, depresiones

It is important to mention that it is only after 20 days of birth or until after the umbilical cord has fallen off that children can receive the massage.

Those who perform this procedure and those who believe in it comment that there are a series of manifestations that accompany this illness, among which the most mentioned are: stomach pain, leg pain, arm pain, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, tendon tightening, sometimes constipation, nervousness, weakness, gas retention, restlessness, dry and bitter mouth. (1)

- dolor estomacal, dolor de piernas, dolor de brazos, fiebre, vomito, diarrea, dolor de cabeza, encogimiento de tendones, en ocasiones estreñimiento, nerviosismo, debilidad, retienen gases, inquietud, boca seca y amarga.

The healing must be carried out by an experienced person, since those who dedicate themselves to this profession comment that if the technique is not carried out correctly, it can cause complications in patients, such as dehydration, a feeling of “stabbing in the chest,” and heart pain, which can lead to a heart attack.

Within its treatment, we can also add the use of some medicinal plants, in tea or tonics. Sometimes, chamomile tea with basil and epazote estafiate is recommended to help calm their nerves and release gas.

When their stomach is full, a tonic for anemia is prepared with the following ingredients: matarique, Indian herb, guaco stick, mulatto stick, viper herb, mountain laurel, alfalfa, nutmeg, a pinch of salt, and a pinch of sugar (except for diabetics).

matarique, hierba del indio (1), palo guaco (2), palo mulato (3), hierba de la víbora (4), laurel de la sierra (5), alfalfa, nuez moscada, pizca de sal, y pizca de azúcar (a excepción de los diabéticos).

- (?) “Hierba del indio” is the common name for various plants in the genus Aristolochia, often called pipevines, which are native to Mexico and other regions. One specific example is Aristolochia quercitorum, a groundcover found in Sonora and Sinaloa, Mexico, which serves as a food source for the Pipevine Swallowtail butterfly. The term can also refer to a tea made from these plants, sometimes sold as “Te del Indio,” though it contains high caffeine and is not recommended for children or pregnant women.

- (?) Palo Guaco, also known by its scientific name Mikania glomerata, is a traditional Hispanic remedy used for respiratory and digestive issues, animal bites, and inflammation. It is prepared as a tea, capsule, or tincture and is known to act as a bronchodilator and expectorant, helping to relax the muscles of the respiratory tract. The plant is found in Central and South America and the West Indies

- (?) Palo mulato refers to the Bursera simaruba tree, also known as gumbo-limbo, due to its red, flaky bark resembling a sunburn. It’s a versatile tree found in the Neotropics, used in traditional medicine to support skin health, wound healing, and for its antioxidant benefits. The bark can be used to make teas, tinctures, and blends for various traditional uses, including alleviating inflammation and digestive issues.

- La hierba de la víbora – Viper’s herb (Zornia diphylla) and viper’s stick (a fern) are plants used in traditional medicine to treat a variety of ailments, from fever and gastrointestinal problems to infections and kidney problems, through infusions and poultices. It is said to have anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, and antioxidant properties, although traditional Mexican medicine emphasizes its use for urinary and menstrual conditions and as a remedy for fever. It should not be consumed for more than four weeks, and its use is not recommended during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

- http://www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/fmim/termino.php?l=4&p=pima&cr=5&t=laurel-sierra&id=118 Pima Medicinal Flora of Yécora, Sonora. – Labrela, Laurel de la sierra – Medicinal use. For the treatment of stomach upset or indigestion: it is recommended to drink one cup three times a day, brewing four bay leaves in one cup of water.

According to the study conducted, it can be said that the causes of inflammation of the large intestine are mainly environmental (dietary) and/or emotional problems. However, according to those dedicated to healing with this method, it is due to “frights, strong impressions, anger, nervousness, and depression”. (1) This can be cured through a well-performed massage.

- “los sustos, impresiones fuertes, corajes, nerviosismo y depresión.”

References

- Aguirre Reyes, Melissa (2008) La sobada de tripa en Sinaloa, México. Tlahui-Medic. No. 26, II/2008. Medicina Tradicional. Escuela de Enfermería, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos. https://www.tlahui.com/medic/medic26/sobadatripa.htm

- Aguirre Reyes, Melissa. Interview with Mrs. Maria Ángela Villegas Rivera . Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico, March 25, 2008. https://www.tlahui.com/medic/medic26/sobadatripa.htm

- Aguirre Reyes, Melissa. Interview with Ms. Silvina Arellanes . Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico, March 25, 2008. https://www.tlahui.com/medic/medic26/sobadatripa.htm

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Burkhart, Louise M; (1996) Holy Wednesday: A Nahua Drama from Early Colonial Mexico (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996), 190.

- Campos-Navarro, Roberto (1993) Notas de campo. Norte de Sinaloa.

- Gonzalez-Swafford MJ, Gutierrez MG. Ethno-medical beliefs and practices of Mexican-Americans. Nurse Pract. 1983 Nov-Dec;8(10):29-30, 32, 34. PMID: 6646536.

- Huxtable RJ. (1998) Ethnopharmacology and ethnobotany along the US-Mexican border: potential problems with cross-cultural “borrowings”. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 1998;41:259-64. PMID: 9836303.

- Kay, Margarita Artschwager. Southwestern Medical Dictionary : Spanish/English, English/Spanish / Margarita Artschwager Kay, with John D. Meredith, Wendy Redlinger, and Alicia Quiroz Raymond. University of Arizona Press, 1977.

- López Austin, Alfredo. The Human Body and Ideology. Thelma Ortiz de Montellano and Bernard R. Ortiz de Montellano, trans. 2 vols. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1988.

- Montoya Briones, Jose de Jesus (1964). Atla: Etnografia de un Pueblo Nahuatl. Mexico City: Mexico City: INAH. p. 165.

- Ochoa Robles, Héctor Antonio (1967) Estudio de sociología médica aplicada a la salud del pueblo yaqui. México, D.F., tesis profesional en medicina, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Rodríguez, Mariángela (1986) Entre el Sol y la Luna: etnohistoria de los mayos. México, D.F., Dirección General de Culturas Populares/Premia, La Red de Jonás.

- Smith, Andrea B (2003) https://ethnomed.org/culture/mexican/

- Sullivan, Thelma & Knab, T.J. (1994), A Scattering of Jades: Stories, Poems, and Prayers of the Aztecs, eds. 208.

- Toor, Frances (1937) “Apuntes sobre las costumbres yaquis”. En: Mexican Folkways. Special Yoqui Number, México, D.F., pp. 52-63.

- Wakefield JC. Diagnostic Issues and Controversies in DSM-5: Return of the False Positives Problem. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12:105-32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112800. Epub 2016 Jan 11. PMID: 26772207.

Websites

- Latido – Diccionario Enciclopédico de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana – http://www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/demtm/termino.php?l=1&t=latido

- Tipos de tripa https://charcutaria.org/en/diversos/como-preparar-a-tripa-natural/?srsltid=AfmBOooR0F6-3vZ3ozadf4Lw0k_dSRHivl3b8hqAr4rPc7H4jD59a71s#google_vignette

- Tripa ida (Definition) Oxford Reference Dictionary – https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803105743997

- Tripa ida (Definition) – Diccionario Enciclopédico de la Medicina Tradicional Mexicana http://www.medicinatradicionalmexicana.unam.mx/demtm/termino.php?l=1&t=tripa-ida

- Tripa ida (Definition) – Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). Improving Cultural Competence. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2014. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 59.) [Table], DSM-5 Cultural Concepts of Distress. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK248426/table/appe.t1/