*DISCLAIMER* Any products shown in this Post are for information purposes only.

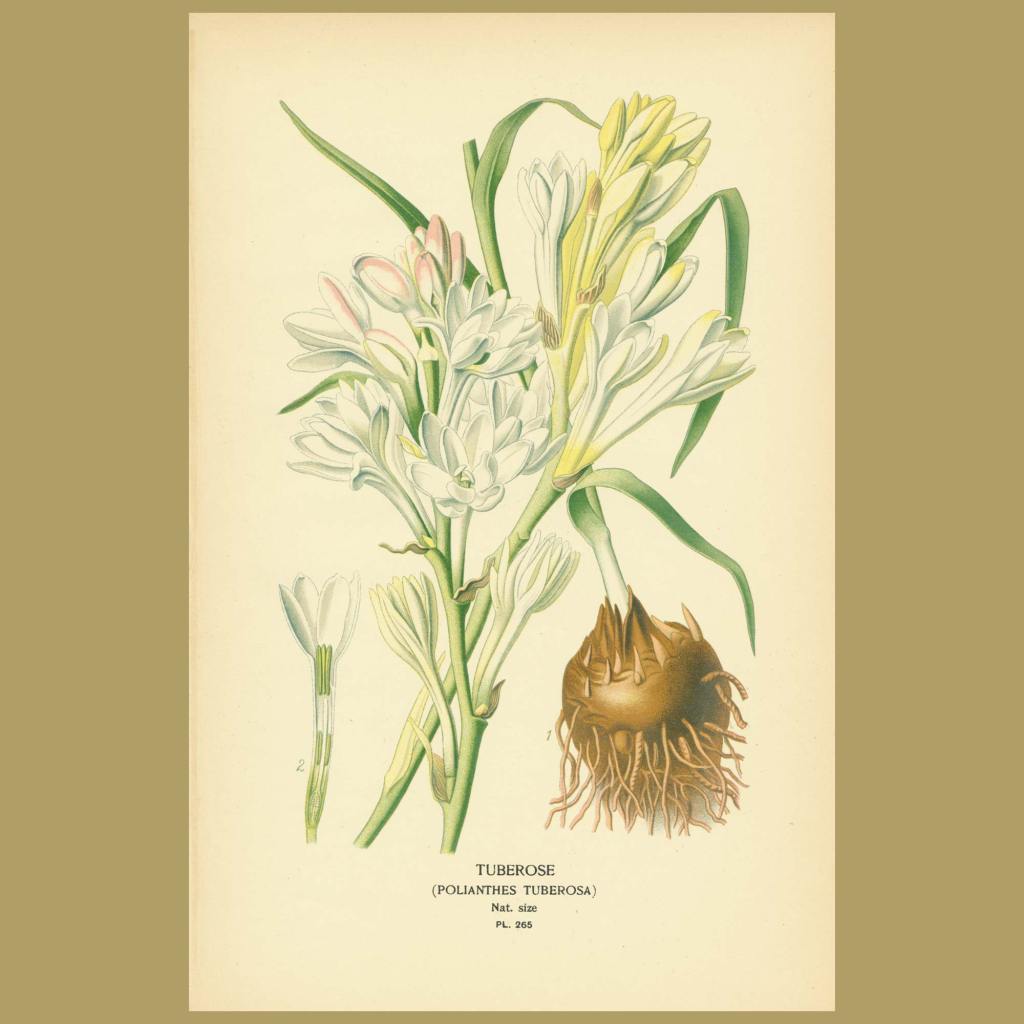

I was researching herbs specific to Tlaloc when a seemingly throwaway line in an article by Ortiz de Montellano (1980) (1) noting that “Certain plants were associated with particular gods: examples include omixochitl (Polianthus tuberosa) with Xochipilli, and cuetlaxochitl (Euphoria pulcherrima) with Xochiquetzal” caught my interest (the section highlighted in BOLD immediately drew me in). I have studied both herbs and plants as well as the being (?)(2) called Xochipilli for many years and I had not come across this plant let alone its association with Xochipilli.

- in the Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl (Studies of Nahuatl Culture) of the Seminario de Cultura Náhuatl del Instituto de Historia de la UNAM. (the Nahuatl Culture Seminar/Conference (or Seminary) of the Institute of History at UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) founded by Ángel María Garibay K. and Miguel León-Portilla in 1949.

- Aztec Gods or States of Consciousness?

Before we progress too far let’s take a look at these two particular giants of Aztec research.

Ángel María Garibay K.

Fray Ángel María Garibay Kintana (18 June 1892 – 19 October 1967) was a Mexican Catholic priest, philologist, linguist, historian, and scholar of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures, specifically of the Nahua peoples of the central Mexican highlands.

Garibay was born in Toluca. While at the Seminario Conciliar de México (1906–1917), he learned Latin and Greek and became interested in Nahuatl language and culture. In subsequent years Garibay also added Hebrew, French, Italian, German, English, and Otomí, to his language repertoire. After being ordained in 1917 he served as a missionary and became more and more focused on his Nahua and Otomí studies. In 1941 Garibay was named prebendary canon (1) of the Basilica of Guadalupe. From 1956 he served as director of the Seminario de Cultura Nahuatl at the Universidad Nacional. In 1952 he was named extraordinary professor at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters at the Universidad Nacional. Garibay is particularly noted for his studies and translations of conquest era primary source documents written in Classical Nahuatl. Alongside his former student Miguel León-Portilla, Garibay ranks as one of the pre-eminent Mexican authorities on the Nahuatl language and its literary heritage.

- A prebendary canon (or simply prebendary) is a type of canon in Anglican or Catholic churches, historically holding a paid position (a “prebend,” often from land income) in a cathedral or collegiate church, but now usually an honorary title for clergy assisting the cathedral or diocese, with specific choir stalls (prebendal stalls) and administrative roles, though often non-resident. Originally, a canon was a cleric living with others in a clergy house or, later, in one of the houses within the precinct of or close to a cathedral or other major church and conducting his life according to the customary discipline or rules of the church

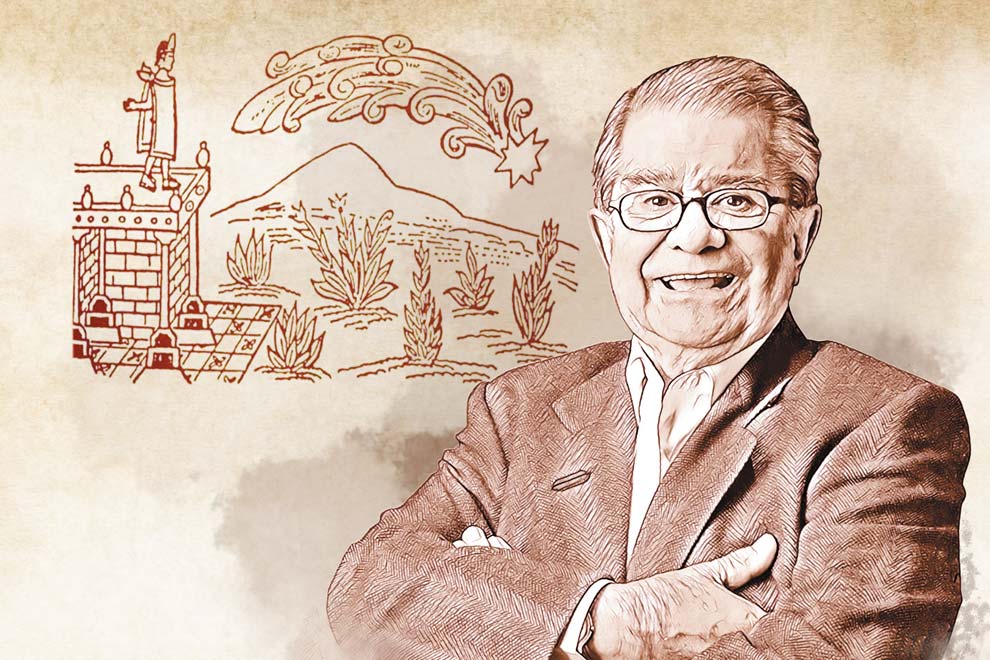

Miguel León-Portilla

Miguel León-Portilla (22 February 1926 – 1 October 2019) was a Mexican anthropologist and historian, specializing in Aztec culture and literature of the pre-Columbian and colonial eras. Many of his works were translated to English and he was an internationally renowned scholar. In 1949, with Angel Maria Garibay, Dr. León-Portilla cofounded the Estudios de Cultura Nahuatl-a centre focused on explorations of the Nahua people and their culture. Since 1959, he has been the primary editor of the centre’s journal, a publication devoted to sharing works on the study of Nahuatl culture. The journal publishes indigenous documentary proof, codices, and historically important texts; ethnographies, both linguistic and cultural; monographs, bibliographies, book reviews, and brief treatises related to the history, archaeology, art, ethnology, sociology, linguistics, literature, and other cultural manifestations of the Nahua people

The culture of the Mexica and others in the Valley of Mexico had a great love for both the beauty and intoxicating scent of flowers. Xochipilli was intimately involved with this aspect of vegetative deification. Strongly scented flowers are associated with Xochipilli (1) and several of these flowers (which bear similarities to omixochitl) are used in the production of top shelf chocolate drinks (2) (3).

- Xochipilli : Intoxicating Scent.

- A Naturopathic View of the Aztec Diet : Part 2 : Appendix 2 : Chocolate Drinks

- Atlaquetzalli. The Drink of Kings*

Later in this article Ortiz de Montellano notes, “There are several methods for demonstrating the close associations between certain plants and a particular god. It can be shown that certain species are closely associated with the rites of certain gods and are not used in the rites of others. A study of the rites performed during the months dedicated to Tlaloc or other water deities will confirm the first point.”

This was my initial task in trying to discover more about the herbs specific to Tlaloc (I was looking for a rainy season – quelite connection) but now I’m going to have to do the same but for Xochipilli

What’s in a name.

omitl = bone : xochitl = flower

omixochitl.

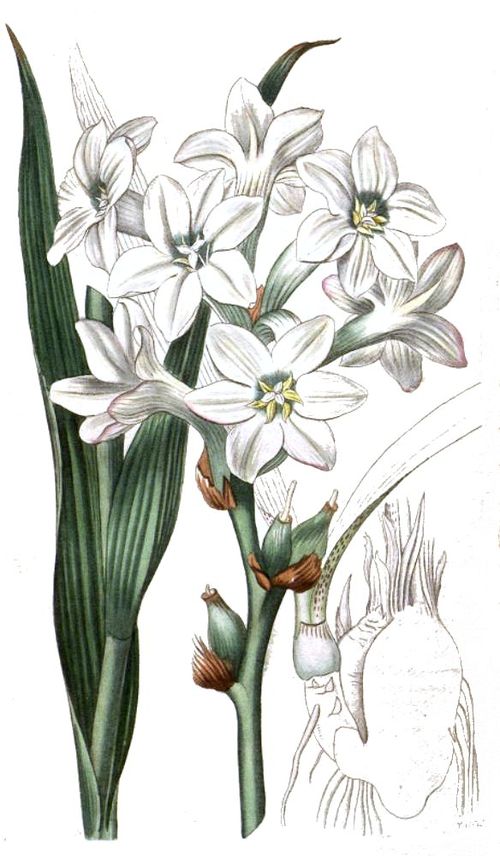

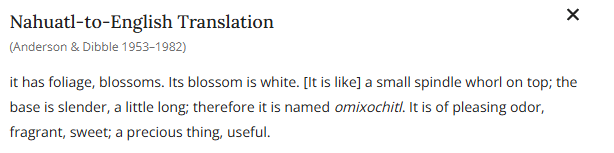

Principal English Translation: a fragrant white lily-like flower (Polyanthes tuberosa, Polyanthes mexicana) (see Karttunen); associated with a deity

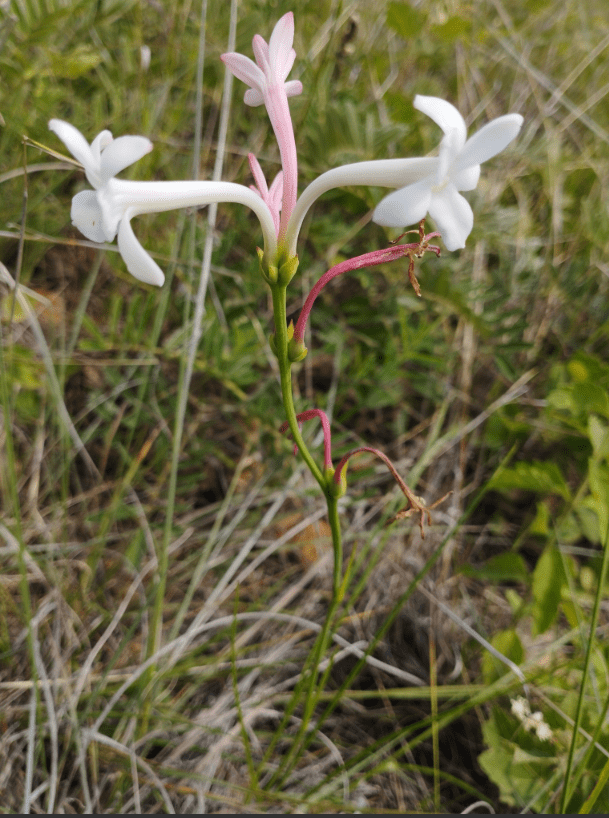

Polyanthes mexicana has been renamed (and reclassified as) Prochnyanthes mexicana and again (like P.tuberosa – more on this in a bit) has since been reclassified as an agave, Agave bulliana (Baker)

OMIXŌCHI-TL a fragrant white lily-like flower (Polyanthes tuberosa, Polyanthes mexicana) / azucena (M), flor de hechura de hueso (C) [(1)Cf.76r). R has the variant OMIYŌXŌCHI-TL See OMI-TL, XŌCHI-TL. (Karttunen 1992)

Omixochitl = the tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa). Etymology suggests bone-flower, and the flower was called flor de hueso in Spanish. Other names include nardo, azucena, amole, and amiga de noche. The flowers are cultivated near Guadalajara. (Trueblood 1973)

omixochitl = Polianthus tuberosa; asociado con el dios Xochipilli (Ortiz de Montellano 1980)

Omixochitl, being an attractive flower with a beautiful scent would certainly have fallen within the realm of the “Prince of Flowers”. See Xochipilli : Intoxicating Scent. for more

The Genus name Polianthus comes from the Greek polios meaning whitish and anthos meaning a flower.

Specific epithet (1) means tuberous.

- In botany, an epithet, specifically a specific epithet, is the second part of a plant’s scientific two-part (binomial) name, following the genus name, used to identify a particular species, like “alba” in Quercus alba (white oak). These epithets, often Latin words describing features (e.g., colour, shape, origin) or honouring people, function like adjectives, differentiating species within the same genus.

The common name derives from the Latin tuberosa through French tubéreuse, meaning swollen or tuberous in reference to its root system.

Names change however and in Botany this can be pretty hectic at times.

Formerly Polianthes tuberosa, Omixochitl is now classified under the Agave family (Asparagaceae) by the moniker

Agave amica.

Agave Amica (Agave Polianthes), Digital Reproduction of an Original Artwork from the 18th Century

Although often referred to as a flower, tuberose is actually a flowering stem, bearing small flowers arranged at its top.

Omixochitl is believed to be native to central and southern Mexico.(1) It is no longer found in the wild, probably as a result of being domesticated by the Aztecs. (2)

- Agave amica (Medik.) Thiede & Govaerts”. World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- it has been in cultivation so long it, like corn, does not occur in the wild state. It is what botanists call a “cultigen” – a plant that does not occur naturally in the wild.

Dimitri (1995) notes that “Polianthes tuberosa or “nard”, from the Latin “nardus” (1), is originally from the Sonora desert in Mexico”.

- Named indirectly from the Greek nardos, the classical name for Spikenard (Valerianaceae). This came to be applied to other aromatic plants, including grasses (e.g. Cymbopogon nardus) then, by other associations, to non-aromatic grasses and finally, by Linnaeus, to several grasses with spicate inflorescences.

Others posit that it may have originated in Jalisco (Mexico) where the similar Agave dolichantha (1) (Thiede & Eggli 1999) which has (fairly) recently been rediscovered in the wild (Cedano et al.1995) (Cházaro & Machuca 1995).

- Synonym Polianthes longiflora

History

Europeans first discovered Omixochitl after the Spanish conquistadors landed in the New World. The Aztecs, Mayans, and other native groups had already been growing the plant. The Aztecs called it bone flower for the white colour of the blooms.

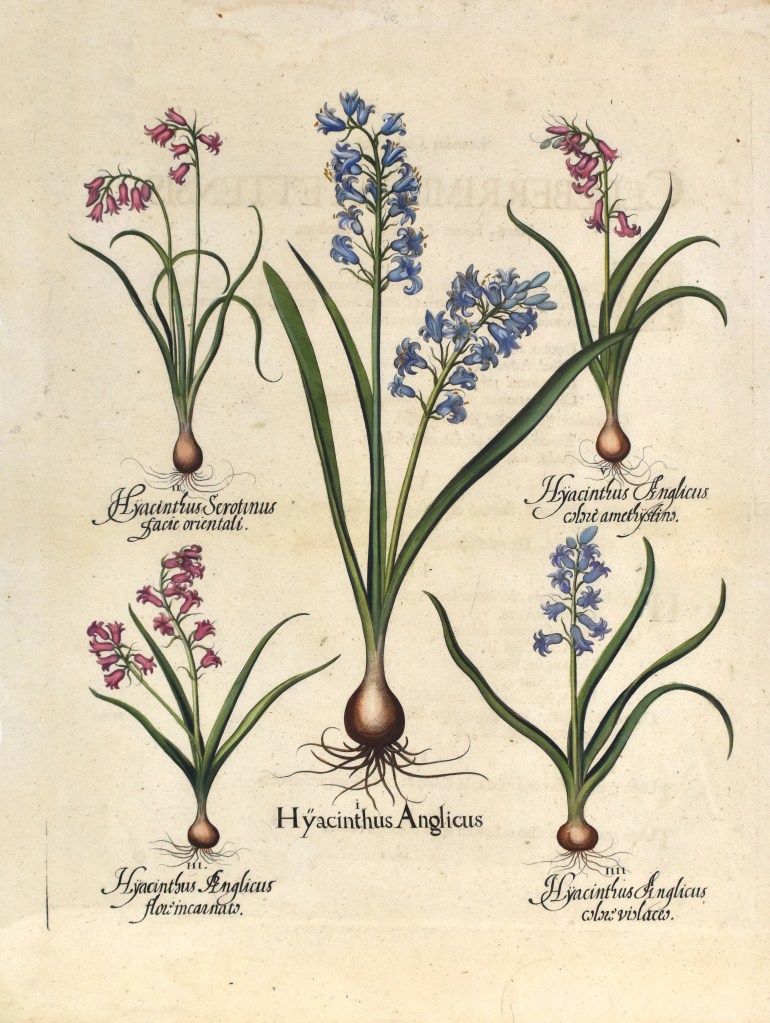

Spanish conquistadors exported the flowers to Europe in the 1590s (where it was called “Hyacinth of the Indies”), and from there Polianthes quickly spread worldwide.

As tuberose it was recorded in Europe by the early 1600’s. In Europe, tuberoses became especially popular in the Victorian era of England. The flower was prized for its fragrance and was used in funerals. It’s possible that the flowers association with death led to a decline in popularity of tuberose.(1)

- Interestingly the Cacahuaxochitl or Quararibea funebris as I noted earlier as being an aromatic blossom used to flavour chocolate (like Tzacxochitl ?) was also a flower associated with funerary rites with its moniker “funebris” coming from Latin, meaning “of or pertaining to a funeral,” derived from the Latin word funus (funeral, corpse, burial rites)

In France, Louis XIV had over 10,000 bulbs brought to his perfumer’s garden at the Trianon and perfumed Versailles with the intoxicating and exotic flowers. By the 17th century, tuberose was being cultivated in Grasse, Provence, Languedoc, and Liguria, and was used primarily to perfume gloves. It continued to travel, reaching the East Indies, but it was only from the late 1940s onward that tuberose cultivation shifted to warmer, drier climates, such as Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, the Comoros Islands, and Egypt.

Tuberose production really took off in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, and by the 1980s, India had become the world’s largest producer. (1)

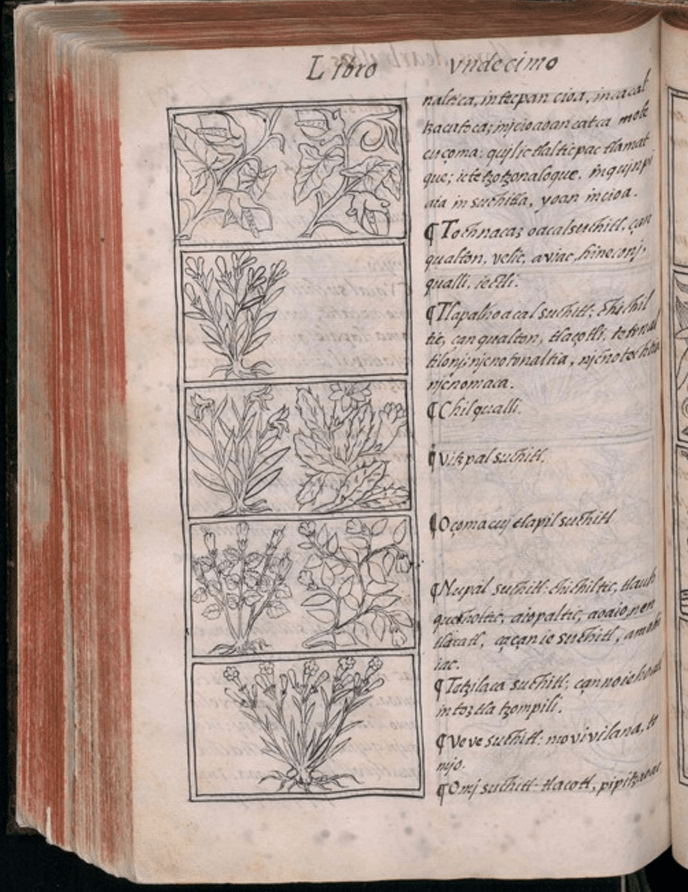

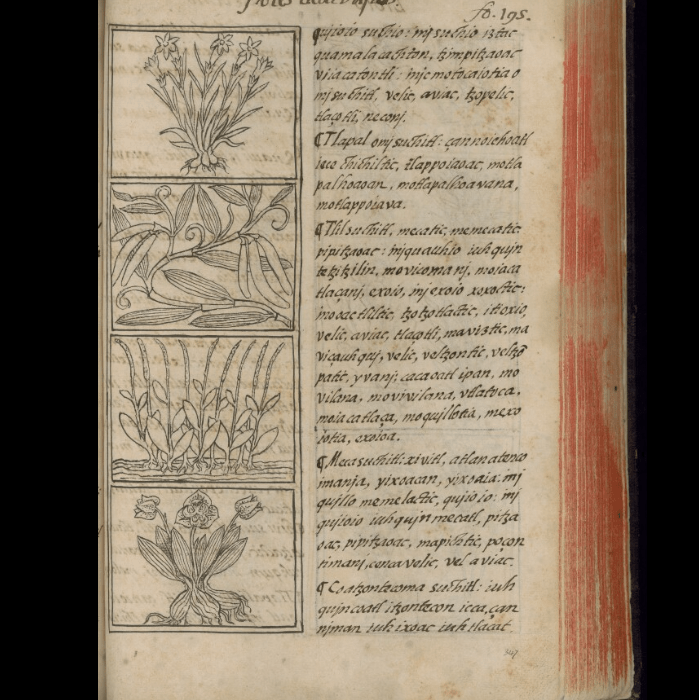

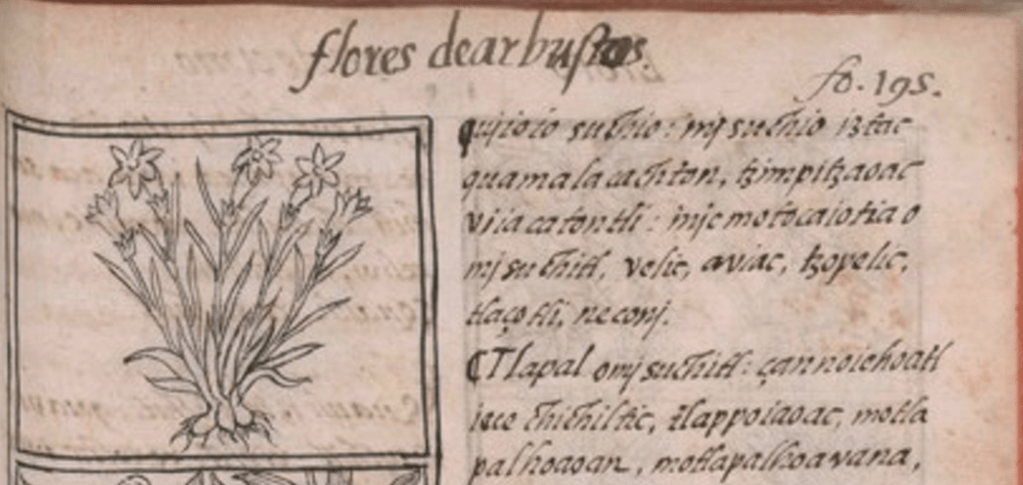

Omixochitl in the Florentine Codex.

Culinary use

Even though P. tuberosa flowers are edible and traditionally consumed in different culinary preparations poor information about their nutritive and antioxidant properties are reported in literature. (Lim 2014)

The flowers are eaten as vegetables (Burkill 1966) (Uphof 1968) (Tanaka 1976) (Kunkel 1984) (Facciola 1990) (Roberts 2000).

In Java, the Chinese cook the flowers in a kind of soup. The cooked flowers are also added to the substrate of ‘kecap’, an Indonesian soy sauce (Stuart 2012)

Fragrant flowers are added along with other ingredients to the favourite beverage prepared from chocolate and served either hot or cold as desired

P. tuberosa flowers contain more ascorbic acid than other well-known edible species, such as Borago officinalis, Bellis perennis and Begonia semperflorens (Grzeszczuk et al 2016)

The stems of the omixochitl containing unopened flower buds are known as Tuberose Bamboo Shoots (1). These crisp buds have evolved into a specialty ingredient sold in asparagus-like bundles in fresh markets throughout Taiwan.

- also known as Tuberose Jade Bamboo Shoots, Tuberose Buds, and Polianthes tuberosa. Despite their “Bamboo Shoot” moniker, the species is unrelated to true bamboo shoots, Phyllostachys edulis

Bamboo shoots (Phyllostachys edulis)

Quoted from the Specialty Produce website.

Tuberose Bamboo Shoots are slender, edible stems topped with a cluster of unopened buds. Each shoot may vary in size and appearance, depending on growing conditions and age at harvest, but generally average 23 to 24 centimetres in length and 0.5 to 1 centimetre in diameter. The petite buds are comprised of tiny, unopened white to green flowers that are encased in a layer of thin, pale green leaves. The flowers typically cascade down the stem in sets of two, and the stem is elongated, pliable, and slightly striated. When snapped in half, the stems have a thick exterior and a fleshy interior, releasing fine, viscous strings. Tuberose Bamboo Shoots are traditionally eaten after lightly cooking. If the stems are sampled raw, they have a notable crisp, aqueous, slippery, and subtly slimy texture. Once cooked, the stems become crunchy, tender, and succulent. The cooked buds also develop a chewy consistency reminiscent of edamame. Tuberose Bamboo Shoots release a faint, vegetal aroma similar to asparagus and the stems have a sweet, mild, green, and grassy flavour. The buds complement the stems with a similar taste and contribute a faint floral undertone.

Both the stems and the buds are edible and have a subtle flavouring, allowing them to be used as a supporting ingredient in main or side dishes. Tuberose Bamboo Shoots should be washed before use, and some consumers choose to peel the stems. The stems and buds can be stir-fried with meat and other vegetables and are often cooked with seafood. The stems and buds can also be steamed or blanched to retain a crisp and crunchy consistency. In Taiwan, Tuberose Bamboo Shoots are popularly blanched, chilled, and tossed with a light dressing as a refreshing salad. The stems and buds are also steamed and served with aromatics or tossed into noodle or rice-based dishes.

In Taipei this “new vegetable” won recognition at the International Food Expo in Singapore in 2010, and has made occasional appearances on various celebrity menus.

In an article in the Taipei Times (April 2017) the author was quite taken by the deliciousness of this vegetable noting that simply steaming it is (so far) the best preparation for it and, having compared it to asparagus, also noted that they would prefer this ingredient over asparagus in any Western or Oriental recipe. They also supply the following recipe as “a guide on how to use the ingredient”

Steamed tuberose with pecorino, black rice and grapes

Recipe (serves 4)

Ingredients

- 1 bunch of tuberose (about 12 stems)

- Extra virgin olive oil, generous splash

- Salt and pepper to season

- Pecorino or other strong, hard cheese such as Spanish Manchego or Italian Parmesan

- Cooked rice (See **NOTES**)

- Seedless black grapes

- Organic nasturtium flowers and young leaves

Directions

1. Peel the stems of the most fibrous outer layer. Bring a steamer to a boil and steam for about 4 to 5 minutes. The stems should still be crisp.

2. Remove from steamer and immediately drizzle the stems with olive oil and sprinkle over a generous quantity of pecorino cheese. Season with salt and pepper.

3. Serve together with rice, sliced seedless black grapes and the flowers and young leaves of organic nasturtium.

**NOTES** Black rice was used in this recipe (for the “colour scheme”), but the author notes that “any good quality rice is fine, though if you have a red or black whole-grain rice to add a bit of sweetness this works remarkably well

Medicinal uses of Omixochitl

Redfield (1928) in “Remedial plants of Tepoztlan: A Mexican folk herbal” notes

“Polianthes (tuberosa L.) Azucena. Omixochitl. This plant does not grow in Tepoztlan, but is imported to combine with a species of Laelia for a use described under the next following name. The plant is probably the same as that known under this name to the ancient Aztecs. The name means “bone flower” and refers perhaps to its colour.”

Redfield also outlines how it was used to medicinally to prevent spontaneous abortions.

Laelia sp. Tzacxochitl. The pseudobulb of this plant is ground with that of Polianthes and boiled with sugar and chocolate. The resulting potion is taken by a pregnant woman to prevent the abortion which would otherwise follow when she conceives a sudden appetite that she is unable to satisfy. “All of a sudden she wants to eat something; she cannot get it; so she takes tzacxochitl so that the child does not fall.” The plant does not grow in Tepoztlan itself, but is obtained from the tezcal, a rocky area on the slopes of the mountain

SEMARNAT (Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales) identifies Tzacxochitl as being the orchid Laelia autumnalis

- Mexico’s federal Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources

Tzacxochitl

Also called

- Nahuatl : Ahuasúchil, Chichitictepetzacuaxóchitl, Petzcuaxochitl, Tzacutli

- Spanish : Diegos, Flor de San Diego, Flor de calavera, Flor de las ánimas, Flor de los santos, Flor de muerto, Flor de muertos, Flor de todos los santos, Flor de ánimas, Lirio de San Francisco

According to Dr. Ayush Varma (an Ayurvedic physician) of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) “Documents dating back to early medieval Ayurveda, including marginal notes in a 12th-century copy of the Sushruta Samhita, mention tuberose as “Rajatika kusuma,” used for its cooling and sedative properties. In Tamil Siddha medicine of the 15th century, poets praised its oil for easing insomnia, and manuscripts at the Thanjavur library describe blending P. tuberosa petals with sandalwood paste for clear complexion and to calm pitta dosha. By the Mughal era, royal perfumers in Rajasthan distilled tuberose water (“attar”) widely for personal fragrance, but Ayurvedic physicians (vaidyas) also noted that inhaling this attar could soothe an anxious mind and reduce episodes of palpitation. In early British colonial herbals of the 1800s, tuberose was briefly catalogued as Polianthes exaltata (an outdated synonym), with dried flowers used in tea or poultices. However its bitter tubers were seldom ingested due to mild gastrointestinal upset.

Medicinal Uses.

In Chinese folk medicine, the tubers are used for the treatment of acute infectious diseases and pyrogenic inflammations (1), burns and swellings.

- Pyrogenic inflammation refers to inflammation caused by pyrogens (fever-inducing substances), often from bacteria (like endotoxins) or immune responses, leading to fever, redness, swelling, pus (due to neutrophil accumulation), and tissue damage, with key mediators being pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α that act on the hypothalamus to reset the body’s temperature. It’s a hallmark of bacterial infections, resulting in symptoms like fever, pain, and potential abscess formation. A pyrogen is any substance, often from bacteria (like endotoxins) or viruses, that causes fever by triggering the body’s immune system to raise its temperature set-point, leading to symptoms like chills and aches.

The tubers are also considered emetic antispasmodic and diuretic. The tubers are dried, powdered and used as a remedy for gonorrhoea and used with turmeric for curing rashes in infants and wound healing in India and also used to treat malaria. Poultice of the tubers are used as maturative (1) in the formation of pus in boils or abscesses.

- Maturative describes something that promotes or relates to the process of maturing, ripening, or developing to a full or final stage, often used in medicine for promoting pus formation (suppuration) or in biology for cell/germ development, and generally for healthy emotional or physical growth, meaning it’s tending towards ripeness or completion.

In aromatherapy, the warm and seductive scent of the tuberose oil is useful as a hypnotic for women suffering from insomnia and depressed with low sexual drive.

Traditional Ayurvedic (1) texts credit tuberose with the following benefits:

- Stress Relief & Sleep Aid: Inhaling tuberose attar before bed calms restless minds, reduces midnight awakenings.

- Skin Soothing: Flower-infused oils or pastes help alleviate rashes, minor burns and inflammatory dermatoses, thanks to antioxidants and gentle cooling.

- Digestive Support: Mild antispasmodic action eases abdominal cramps and flatulence when flowers are steeped in warm water.

- Uterine Comfort: Traditional poultices made with tuberose petals help relieve dysmenorrhea (menstrual cramps) in women.

- Emotional Balance: Aromatherapy uses reduce symptoms of mild depression and nervous tension, aligning with Ayurvedic rasayana purposes (2).

- Ayurveda is an ancient Indian holistic system of medicine, translating to “knowledge of life,” that balances mind, body, and spirit through diet, herbs, yoga, meditation, and lifestyle changes, aiming to prevent illness and promote longevity by balancing three vital energies, or doshas: Vata, Pitta, and Kapha

- Rasayana is a specialized branch of Ayurveda practiced in the form of drug, diet and special health promoting conduct and behaviour.

Dosage.

In Ayurvedic medicine Polianthes tuberosa is used in several ways

- Dried Flowers: 1–2 g decoction in 150 ml water, sipped twice daily for mild insomnia or digestive discomfort.

- Essential Oil: 2–4 drops inhaled via diffuser or steam inhalation; or diluted at 1–2% in a carrier oil for topical use.

- Flower-Infused Oil: 5–10 ml applied externally to inflamed skin or as a warm abdominal massage oil.

- Tincture/Extract: 10–20 drops (0.5–1 ml) in water, once daily, for emotional balance and uterine comfort.

WARNINGS

Safety note: Avoid undiluted essential oil on skin as it can cause irritation. Not recommended for pregnant women in high doses (inhalation at low levels ok) or infants under two due to potency. Elderly, and those with severe respiratory issues should test a single drop in diffuser before routine use.

Other uses

Various folk medicinal uses of the plant include being used for tumours, cosmetic, laxative, cooling, placebo, sexual disorder, hair colour, emetic, diuretic, and gonorrhoea. (Rahmatullah et al 2019)

Pharmacological studies indicate that the plant has anti-microbial, antioxidant, anti-viral, immunomodulatory, diabetic wound healing, anti-inflammatory, anti-amoebic, anti-ulcer, and neuropharmacological properties. (Rahmatullah et al 2019)

Flowers are used in perfume industry and also for their diuretic and emetic activity (1). The peuedobulbs are used for anti-gonorrhoea, diuretic, emetic actions, and for curing rashes in infants (specific application not noted in this case – See WARNINGS above with reference to use in children) (Rumi et al 2014)

- An emetic is a substance or agent that causes vomiting (emesis)

Ethnomedicinal uses of the plant or plant parts (Mandal et al 2022)

The plant (or parts of the plant) also have medicinal uses in other countries apart from Bangladesh. The plant is used for gonorrhoea, insomnia and low sex drive by people of Kollihills, Namakkal district, Tamil Nadu, India.

Flowers are taken as tea in the Dominican Republic for women’s health conditions.

Studies have evaluated the antioxidant, cytotoxic, antimicrobial, membrane stabilizing and thrombolytic activities of P. tuberosa as well as to find evidence for its folk uses. (Rumi et al 2014)

Reported Pharmacological Activities (Mandal et al 2022)

- The flower and bulb extracts of the plant were shown to have anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic, diuretic and emetic properties. Bulbs are also used for curing rashes in infants

- It is reported that bud extracts of the plant possess larvicidal and biting deterrence activity against Anopheles stephensi and Culex Quinque fasciatus

- The tuberose flower methanolic extract had strong antibacterial activity against Proteus mirabilis and Esherichia coli

Other medicinal uses have been posited due to the geraniol contents. (Mandal et al 2022)

- Anti-tumor activity: Geraniol (trans-3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadien-1-ol) has been shown to possess anti-tumor properties.

- Anti-inflammatory activity: Geraniol also has pharmacological potential in lung inflammatory diseases where oxidative stress is a critical factor.

- Antibacterial activity: Essential oil containing geraniol as the active compound exhibited a broad inhibition spectrum against ten Escherichia coli serotypes: three enterotoxigenic (1), two enteropathogenic (2), three enteroinvasive (3) and two shiga toxin (4) producers.

- Anthelmintic activity: The volatile oil containing geraniol, showed anthelmintic activity by causing paralysis and death of the Indian earthworm Pheretima posthuma

- “Enterotoxigenic” describes bacteria, particularly E. coli (ETEC), that produce toxins (enterotoxins) causing watery diarrhea by disrupting ion channels in the small intestine, leading to fluid loss, and is a leading cause of “traveler’s diarrhea” and infant illness in developing countries, often spread through contaminated food or water. These bacteria use colonization factors to attach to the intestinal lining, then release heat-labile (LT) and/or heat-stable (ST) toxins, resulting in cramps, nausea, and severe diarrhoea

- “Enteropathogenic” means able to cause disease in the intestinal tract, referring to infectious agents like bacteria or viruses that target the intestines, leading to symptoms such as diarrhoea, especially in children. A common example is Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), a specific type of bacteria known for causing watery diarrhoea and significant illness, particularly in young children globally.

- “Enteroinvasive” describes bacteria, most famously Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC), that can actively invade (penetrate and enter) the cells lining the intestinal wall, multiply inside them, and spread to adjacent cells, causing inflammation, cell damage, and symptoms like watery or bloody diarrhoea (dysentery)

- Shiga toxin (Stx) is a potent bacterial toxin produced by certain E. coli (STEC) and Shigella dysenteriae, causing severe gastrointestinal illness, bloody diarrhoea, and potentially life-threatening Haemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS), which damages kidneys, especially in young children, elderly, and immunocompromised individuals, transmitted via contaminated food/water or contact with infected faeces. It works by damaging cell ribosomes, halting protein production, and is prevented by good hygiene, thorough cooking, and avoiding unpasteurized products, as antibiotics aren’t recommended and can worsen outcomes.

Other uses

Due to the high concentration of sapogenin in their rhizomes and tuberous roots, many species (including P.tuberosa, P.geminiflora, P.graminifolia Rose) have been used as soap substitutes. For this use, these species are known by the Nahuatl name “amole” which signifies soap, and are also called omolixochitl or omilxochitl (soap flower in Nahuatl) (Rose 1903) (Trueblood 1973)

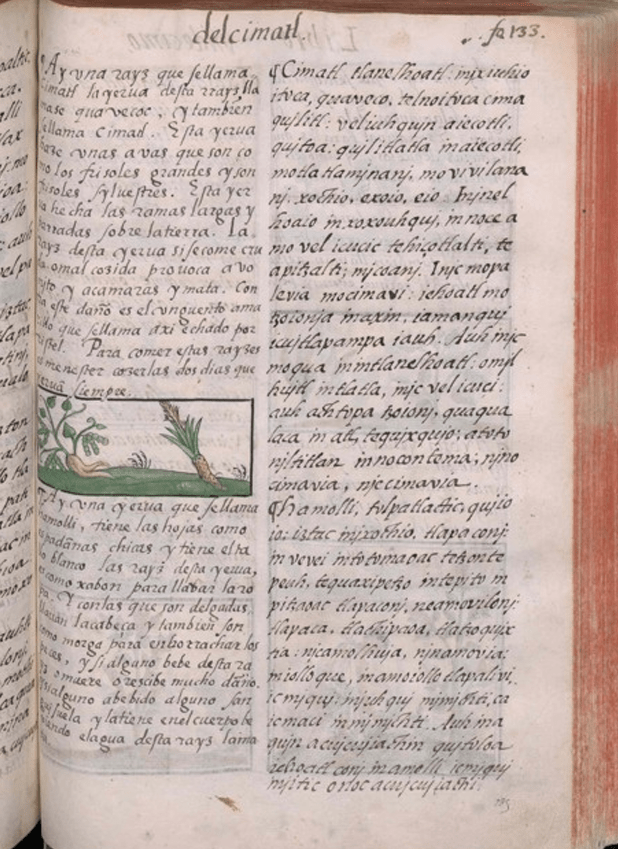

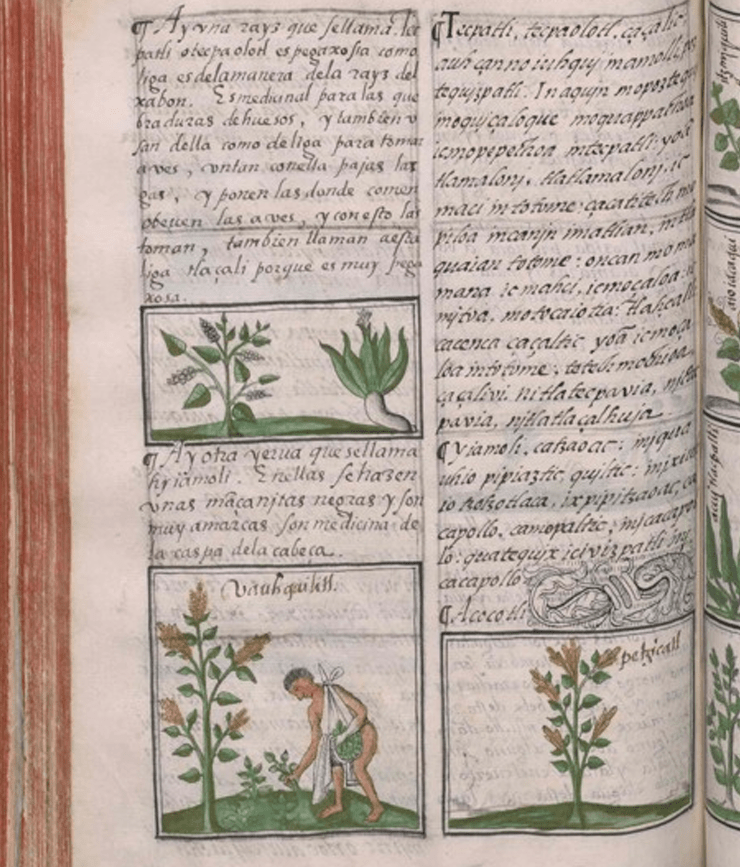

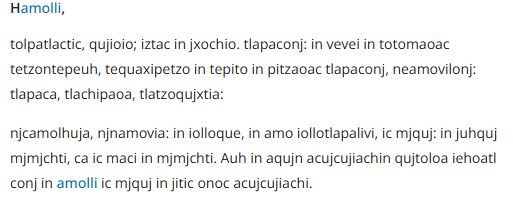

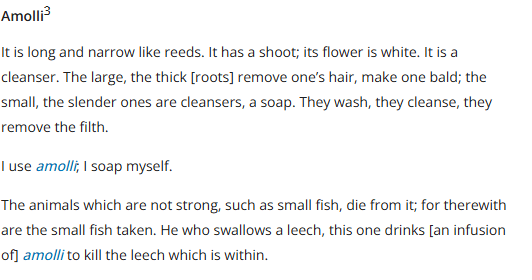

amolli.

Principal English Translation: soap that derives from a plant root (see Karttunen and Lockhart)

Frances Karttunen: AHMŌL-LI soap / raíz conocida que sirve de jabón (R). In the derived form AHMOHUIĀ the vowel of the second syllable is short, and the L is lost. See AHMOHUIĀ. (Karttunen 1992)

James Lockhart (Nahuatl as Written): ahmōl-li = soap (Lockhart 2001)

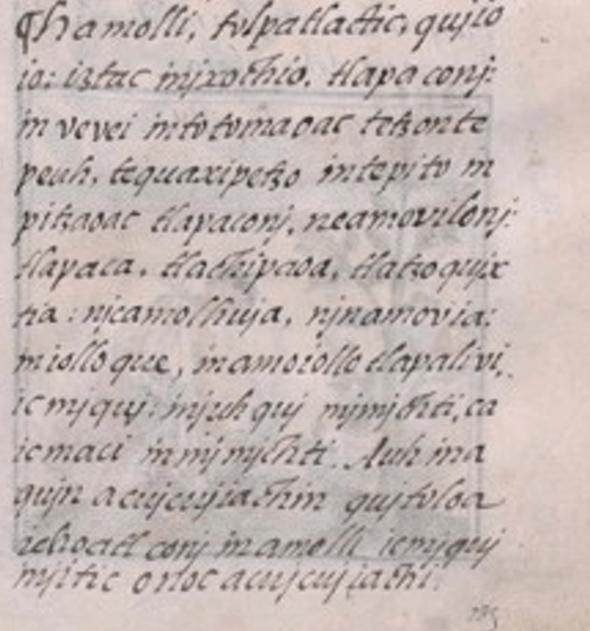

The Florentine Codex provides an illustration and a textual description of amolli (spelled hamolli in that manuscript). Above ground it has long, narrow reeds. Below ground, it has two types of roots. The smaller ones are used for soap, such as for washing one’s hair. The larger roots can make one go bald. It can serve as a remedy; if one eats a leech, one needs to swallow an infusion of amolli. Small fish find amolli too toxic and can die from it.

Hay una yerba que se llama amolli. Tiene las hojas como espadañas chicas, y tiene el tallo blanco. La raíz desta yerba es como xabón para lavar la ropa. Y con las que son delgadas lavan la cabeza. Y también son como morga para enborrachar los peces. Y si alguno bebe desta raíz, o muere o recibe mucho daño. Y si alguno ha bebido alguno sanguisuela y la tiene en el cuerpo, bebiendo el agua desta raíz la mata.

There is an herb that is called amolli. Its leaves are like small cattails, and it has a white stalk. This herb’s root is like soap for washing clothes. And they wash their heads with the ones that are thin. And they are also like the fishberry that is used to stun fish. And if someone drinks from this root, [this person] either dies or becomes very ill. And if someone happens to swallow a leech and has it inside his or her body, this person can kill it by drinking the water of this root.

Research continues.

References

- Alghuthaymi MA, Patil S, Rajkuberan C, Krishnan M, Krishnan U, Abd-Elsalam KA. Polianthes tuberosa-Mediated Silver Nanoparticles from Flower Extract and Assessment of Their Antibacterial and Anticancer Potential: An In Vitro Approach. Plants (Basel). 2023 Mar 10;12(6):1261. doi: 10.3390/plants12061261. PMID: 36986949; PMCID: PMC10054782.

- BARGHOUT N, CHEBATA N, MOUMENE S, KHENNOUF S, GHARBI A, EL HAD DI. Antioxidant and antimicrobial effect of alkaloid bulbs extract of Polianthes tuberosa L. (Amaryllidaceae) cultivated in Algeria. J. Drug Delivery Ther. [Internet]. 2020 Jul. 15 [cited 2025 Dec. 19];10(4):44-8. Available from: https://jddtonline.info/index.php/jddt/article/view/4134

- Burkill IH (1966) A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. Revised reprint, 2 vols. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur, vol 1

- Cedano Maldonado, M., Ramirez Delgadillo, R. & Enciso Padilla, I. (1993 [publ. 1995]) Una nueva espécie de Polianthes (Agavaceae) del Estado de Michoacán y nota complementaria sobre Polianthes longiflora Rose. Boletin del Instituto de Botanica, Universidad de Gudalajara 1: 521–530.

- Cházaro Basáñez, M.J. & Machuca Núñez, J.A. (1995) Nota sobre Polianthes longiflora Rose (Agavaceae). Cactaceas y Suculentas Mexicanas 30: 20–22.

- Chopra RN, Nayar SL, Chopra IC (1986) Glossary of Indian medicinal plants (Including the supplement). Council Scientifi c Industrial Research, New Delhi, 330pp

- Dimitri, M. Enciclopedia Argentina de Agricultura y Jardinería. 2.a ed., vol. 1, edit. Editorial ACME, 1995, ISBN 950-566-127-4.

- Facciola S (1990) Cornucopia: a source book of edible plants. Kampong Publications, Vista, 677pp

- González Vega, María E. (2016) Revisión bibliográfica Polianthes tuberosa L.: revisión de sus aspectos filogenéticos, morfológicos y de cultivo (Review Polianthes tuberosa L.: a review of their phylogenetic, morphologic and of cultivation features) Cultivos Tropicales, 2016, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 120-136 : ISSN print: 0258-5936 ISSN online: 1819-4087 : DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.2715.4161. http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.2715.4161

- Grzeszczuk, M; Stefaniak, A & Pachlowska, A (2016) “Biological value of various edible flower species,” Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Hortorum Cultus, vol. 15, pp. 109-119, Jan. 2016.

- Karttunen, Frances.; (1992) An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. 2nd ed. Austin: University of Texas Press

- Kunkel G (1984) Plants for human consumption. An annotated checklist of the edible phanerogams and ferns. Koeltz Scientifi c Books, Koenigstein

- Kuppast IJ, Akki KS, Gudi PV, Hukkeri VI (2006) Wound healing activity of Polianthes tuberosa bulb extracts. Indian J Nat Prod 22(2):10–13

- Lim, T.K.. (2014). Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 7, Flowers. 10.1007/978-94-007-7395-0.

- Mandal, R., Singh, N. P., & Mukopadayay, S. (2022). A review on ethnomedicinal properties on polianthestuberosa L. International Journal of Health Sciences, 6(S3), 9728–9743. https://doi.org/10.53730/ijhs.v6nS3.8550 https://sciencescholar.us/journal/index.php/ijhs/article/view/8550/4888

- Ortiz de Montellano, Bernard. (1980). Las Hierbas de Tlaloc. Estudios de cultura náhuatl. 14.

- Ortiz de Montellano, B. (1980). Las hierbas de Tláloc. Estudios De Cultura Náhuatl, 14, 287–314. Recuperado a partir de https://nahuatl.historicas.unam.mx/index.php/ecn/article/view/78429

- Pérez-Arias, G. A., Alia-Tejacal, I., Colinas-León, M. T., Valdez-Aguilar, L. A., & Pelayo-Zaldívar, C. (2019). Postharvest physiology and technology of the tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa L.): an ornamental flower native to Mexico. Horticulture, Environment, and Biotechnology, 60(3), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13580-018-00122-4

- Rahmatullah, Roshni Nahar; Jannat, Khoshnur; Islam, Maidul; Rahman, Taufiq; Jahan, Rownak & Rahmatullah, Mohammed (2019) A short review of Polianthes tuberosa L. considered a medicinal plant in Bangladesh : Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies 2019; 7(1): 01-04

- Redfield, R. (1928). Remedial plants of Tepoztlan: A Mexican folk herbal. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 18(8), 216–226. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24522654

- Roberts MJ (2000) Edible and medicinal flowers. New Africa Publishers, Claremont, 160pp

- Rose, JN. (1903) Studies of Mexican and Central American Plants. Contributions from the U.S National Herbarium 3, 1-55

- Rumi, Farhana Md; Kuddus, Ruhul & Chandra Das, Sujan (2014) Evaluation of Antioxidant, Cytotoxic, Antimicrobial, Membrane Stabilizing and Thrombolytic Activities of Polianthes tuberose Linn : British Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 4(17): 2106-2115, 2014

- Stuart GU (2012) Philippine alternative medicine. Manual of some Philippine medicinal plants. http://www.stuartxchange.org/OtherHerbals.html

- Tanaka T (1976) Tanaka’s cyclopaedia of edible plants of the world. Keigaku Publishing, Tokyo, 924pp

- Thiede, J. & Eggli, U. (1999) Einbeziehung von Manfreda Salisbury, Polianthes Linné und Prochnyanthes S. Watson in Agave Linné (Agavaceae). Kakteen und andere Sukkulenten 50: 109–113.

- Thiede, Joachim; & Govaert, Rafaël (2017) New combinations in Agave (Asparagaceae): A. amica, A. nanchititlensis, and A.quilae. Phytotaxa 306 (3): 237–240. ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition); ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.306.3.7

- Trueblood, Emily Emmart. ““Omixochitl”—the tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa).” Economic Botany 27 (1973): 157-174.

- Uphof JCTh (1968) Dictionary of economic plants, 2nd edn. (1st edn. 1959). Cramer, Lehre, 591pp

- Verhoek, S. (1978). Huaco and Amole: A Survey of the Uses of Manfreda and Prochnyanthes. Economic Botany, 32(2), 124–130. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4253919

Images

- Agave Amica (Agave Polianthes), Digital Reproduction of an Original Artwork from the 18th Century : https://www.meisterdrucke.ie/fine-art-prints/Unbekannter-K%C3%BCnstler/1482499/Tuberose,-Agave-Amica-%28Agave-Polianthes%29,-Digital-Reproduction-of-an-Original-Artwork-from-the-18th-Century.html

- Aztec month Tecuilhuitontli : https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/722656/view/aztec-month-tecuilhuitontli-16th-century

- Miguel Leon Portilla : domingo, diciembre 21, 2025 ÓRGANO INFORMATIVO DE LA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO : https://www.gaceta.unam.mx/miguel-leon-portilla-espiritu-renacentista-de-nuestro-tiempo/

- Omixochitl botanical drawing : Dominio público, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2696964

- Polianthes tuberosa rhizome : By SKsiddhartthan – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=57785099

- Polianthes longiflora : Zapopan, Jalisco, Mexico : Image by moises_perez; https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/129943598

- Prochnyanthes Mexicana – https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/290854-Prochnyanthes-mexicana

- Prochnyanthes Mexicana flower : image by Sinaloa Silvestre – https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/307887889

Websites

- amolli. (Definition) – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/amolli

- An asparagus by any other name : Taipei Times Sat, Apr 01, 2017 – https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2017/04/01/2003667849

- omixochitl. (Definition) https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/omixochitl

- Specialty Produce : Tuberose Bamboo Shoots : https://specialtyproduce.com/produce/Tuberose_Bamboo_Shoots_24958.php#:~:text=Tuberose%20Bamboo%20Shoots%20have%20a,in%20main%20or%20side%20dishes.