Cover Image : Article from The Observer, Sunday 15th. October 2006 referencing the discovery of the Tlaltecuhtli monolith (more on this later)

Under the streets of México City Tenochtitlan lies sleeping.

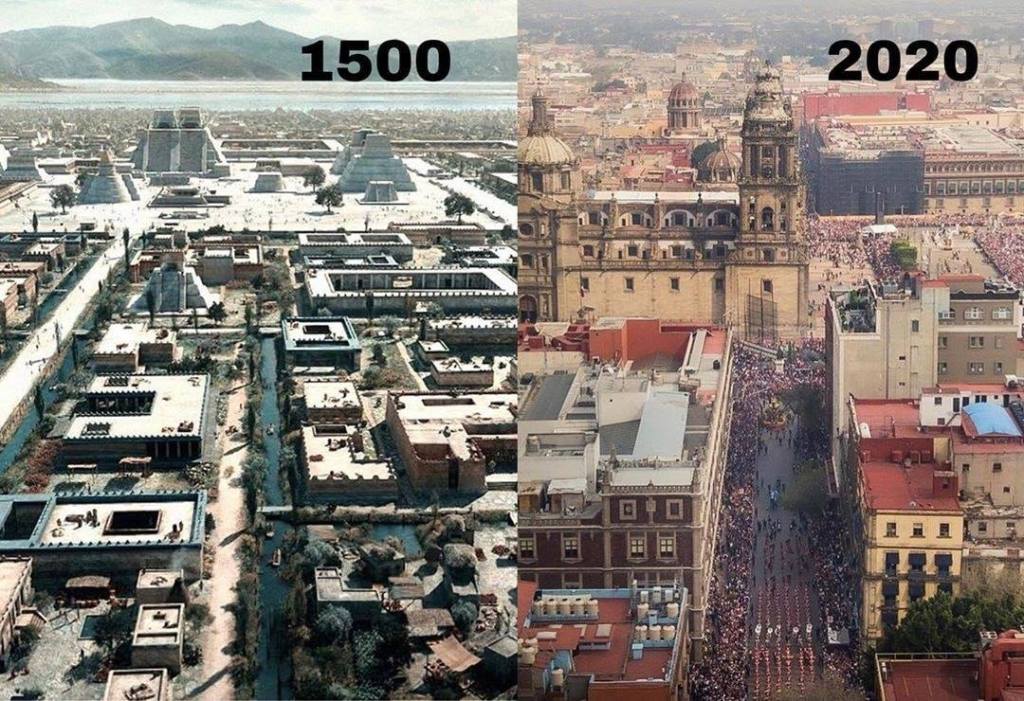

México City was constructed upon the ruins of Tenochtitlan and from the very bones of Tenochtitlan itself. The temples were pulled apart and used to construct the palaces and churches and, in some cases, the stones were left in their original state.

A few blocks from the Zocalo Metro station in Mexico City (wander down Avenida José María Pino Suárez for three blocks and turn left onto Republica de El Salvador) you can find the jowls of a plumed serpent protruding from the base of a building previously known as El Palacio de los Condes de Santiago de Calimaya. This stone was used by the Spaniards as a cornerstone (1) for the construction of the building and, although it is said to represent “a not-so-subtle message signifying the triumph and superiority of European architecture and civilization over the indigenous Aztec empire” I find it has alternative meaning. To me it represents the fact that not only have the Mexica not been subjugated but that they also form the very foundation of the current society and in fact support it from the very ground up.

- a corner stone (or foundation-stone) is the first stone placed upon a building’s foundation, it is a stone that forms part of a corner or angle in a wall, it bears much of the weight of a building’s outer structure, and it connects and unites two of the walls. After it is placed, all other stones and their angles are measured out from it. It can also be used metaphorically to refer to something that is essential or fundamental to a particular system or organization. Cornerstones symbolized “seeds” from which buildings germinate and rise

As an interesting aside, in August of 2020 the Zocalo Metro station was renamed to reference its origins.

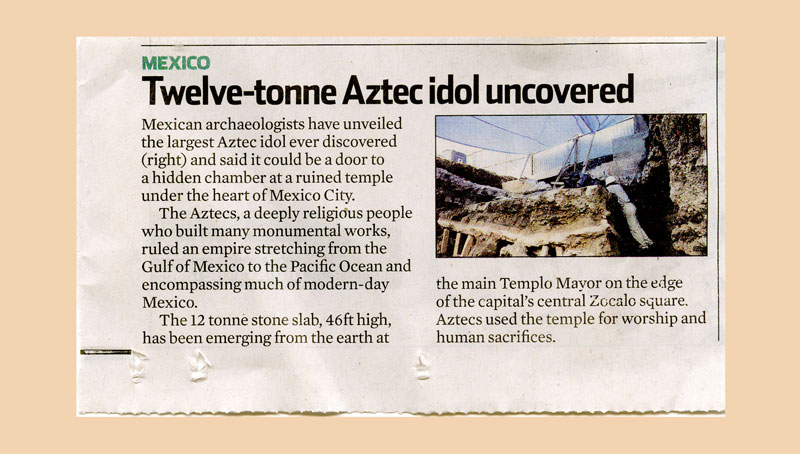

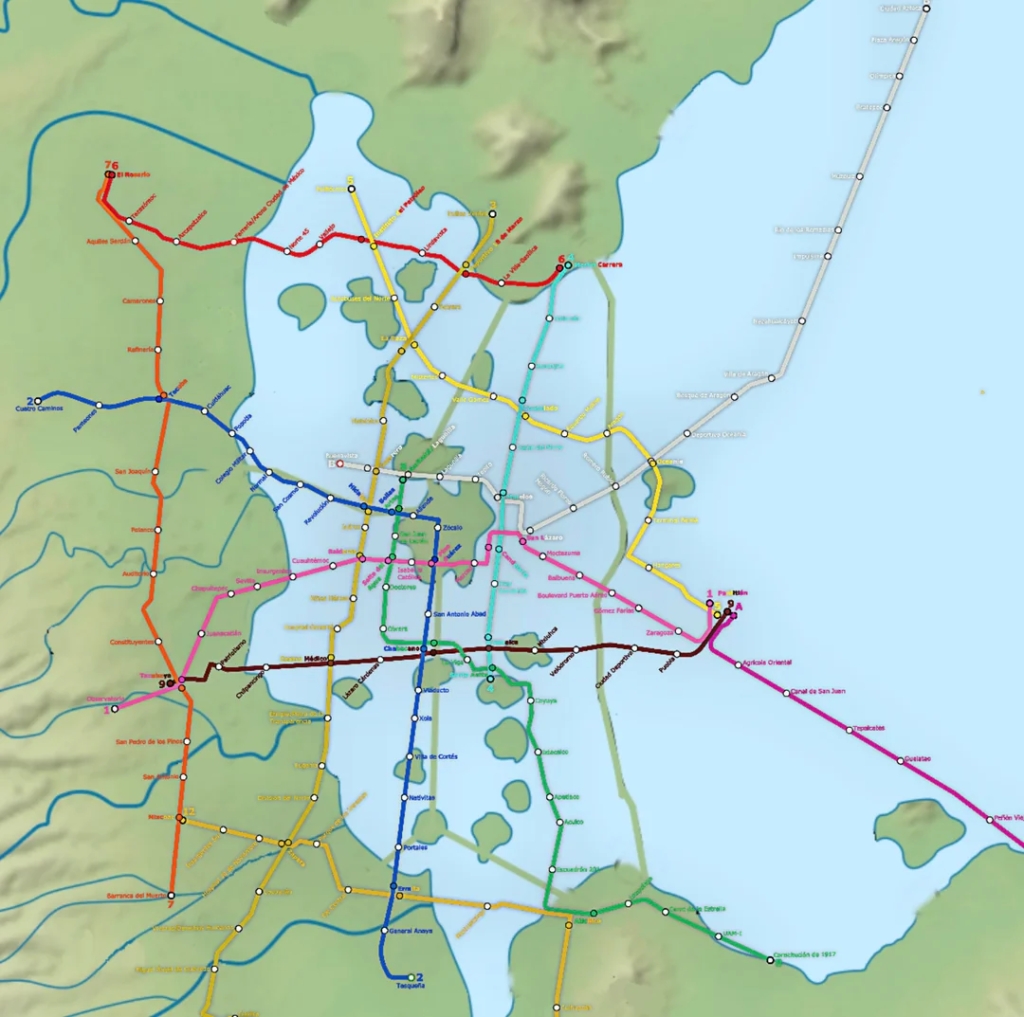

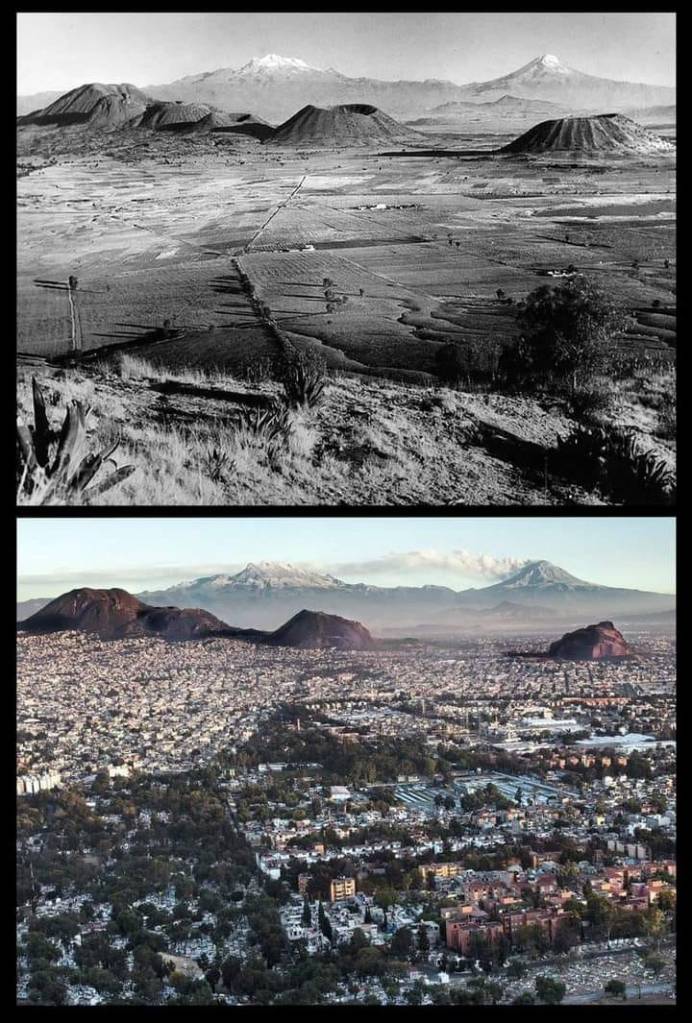

This city (and its surrounding neighbours) once existed within a series of five lakes which have now largely been drained and the exposed land consequently built upon.

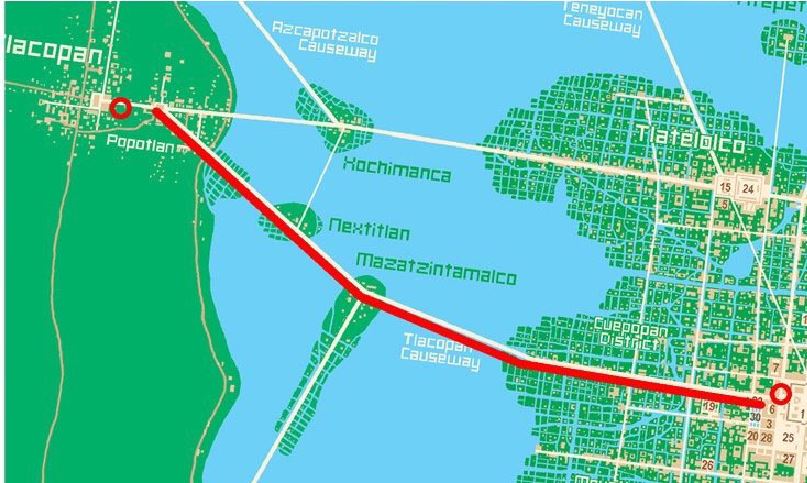

The Valley contained five lakes from the northernmost lake Lago Zumpango flowing south into Lago Xaltocan (both of which were brackish water lakes)(1) then into the wide lake of Lago Texcoco (on which the Aztec island capital, Tenochtitlán, was founded in 1325 AD) and then further southward into Lagos Xochimilco and Chalco which were freshwater lakes.

- Brackish water is a broad term used to describe water that is more saline than freshwater but less saline than true marine environments. Often these are transitional areas between fresh and marine waters. An estuary, which is the part of a river that meets the sea, is the best known example of brackish water.

Each lake was located at different altitudes ranging from 3 to 6 m above Lake Texcoco. All of these lakes were interconnected and due to the differences in altitudes they were prone to flooding any time it rained heavily. This caused frequent issues with the freshwater lakes being polluted by the brackish waters of Zumpango and Xaltocan.

Its causeways and the dyke of Nezahualcoyotl

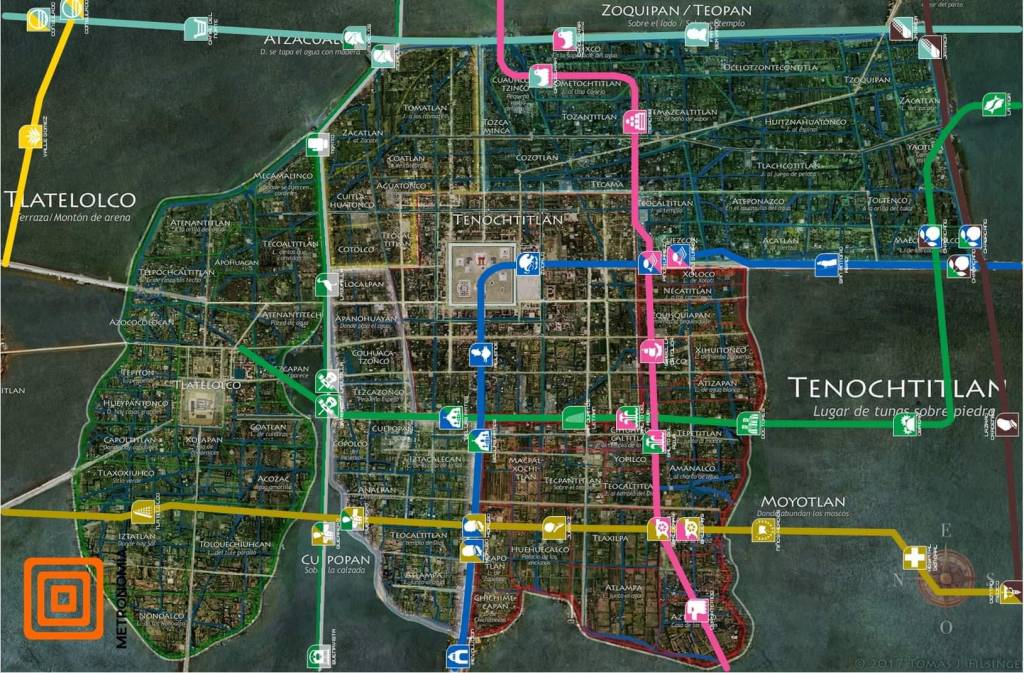

(Tomas Filsinger)

This problem was largely solved by the creation of a 16 kilometre long dyke created by the Poet-King Nezahualcoyotl (1) which separated the brackish waters of the northern lakes from Lagos Texcoco, Xochimilco and Chalco. You can see this dyke at the right of the image above.

- construction of the dyke was completed circa 1453 AD.

Nezahualcoyotl (Fasting, or hungry, Coyote) (1402-1472), poet-king, warrior, architect, statesman and philosopher/sage was the leader of the Acolhua people and ruler of the city-state of Texcoco. One of the key leaders of the Aztec “Triple Alliance” (1), Nezahualcoyotl has been called “the wisest ruler that had ever ruled over the Valley of Anahuac. (2)

- The Triple Alliance of Itzcoatl of the Nahua Mexica of Tenochtitlan who allied with Nezahualcoyotl of the Acolhua of (Tetzcohco) Texcoco and Totoquihuatzin of the Tepanecas of Tlacōpan to establish what is commonly known now as the Aztec Empire. See my Post The Triple Alliance

- Anahuac = A(tl) “water” and -nahuac “place nearby/next to = land near the, or between the waters. This is a perfect description of the lacustrine environments in the Valley of Mexico

Tenochtitlan at its peak. A city of canals. A city far grander, more beautiful and waaaay cleaner than the more commonly known city of canals in Venice Italy.

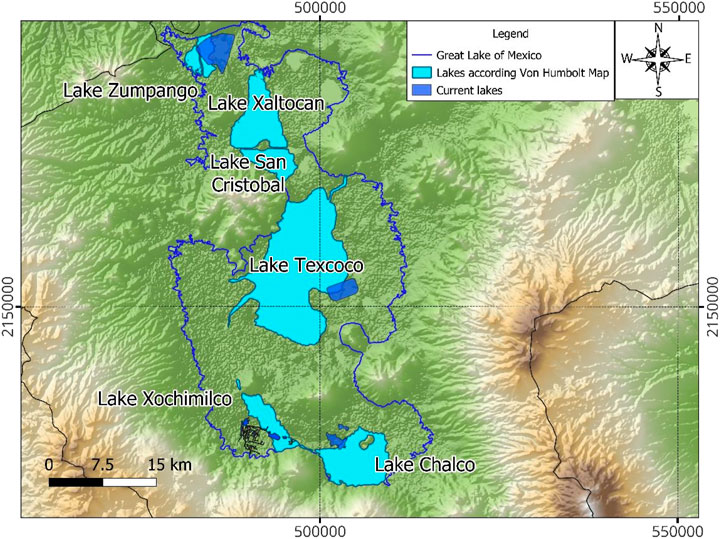

The behemoth that is the Ciudad de Mexico.

The city has expanded to cover all the land that was once underwater.

Tenochtitlan has, and continues to, grow far beyond its previous boundaries.

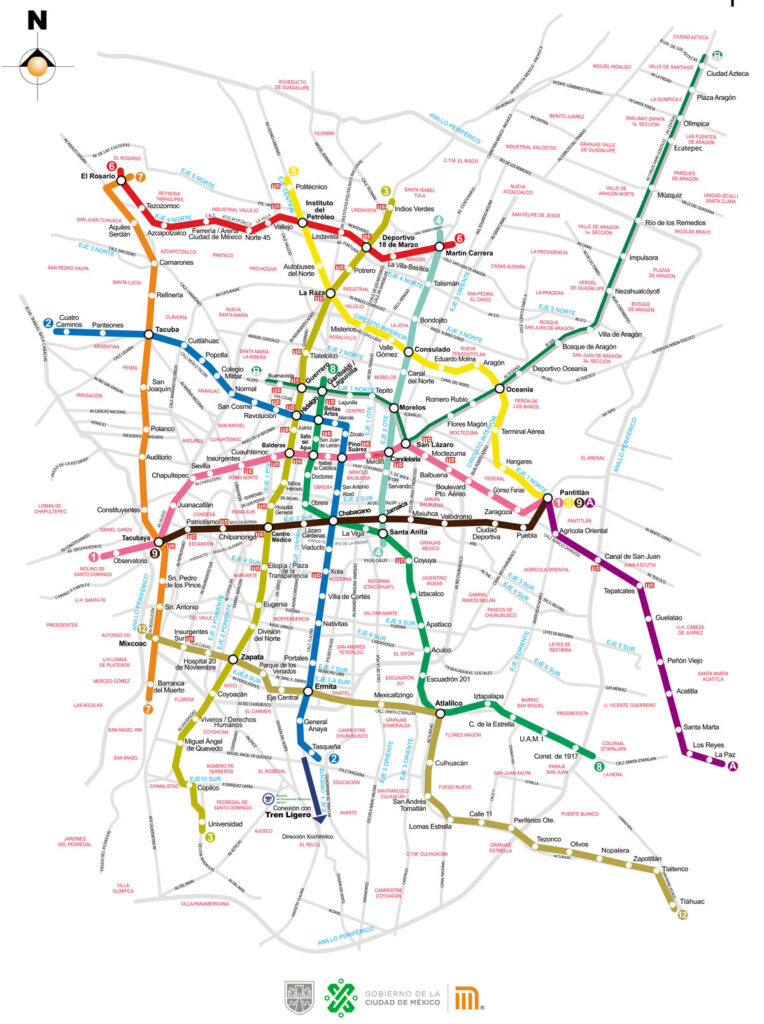

A prime example of this growth is the city’s public transport system, the Metro

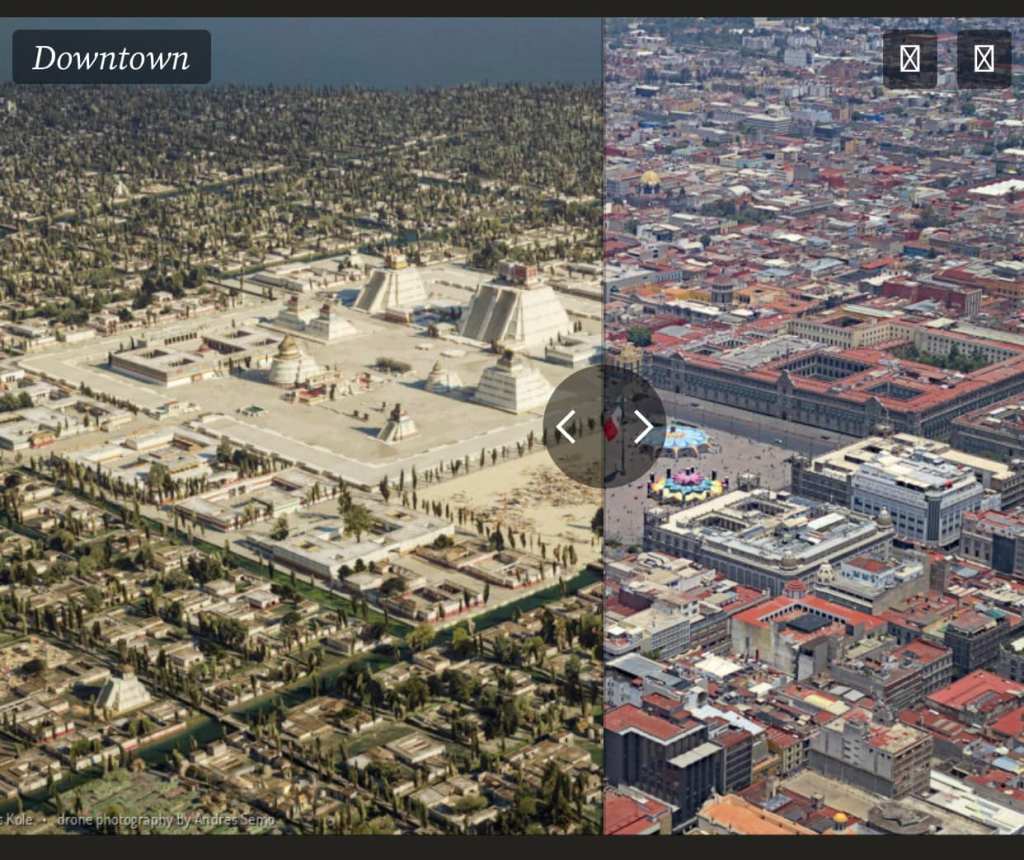

As previously noted the city was simply laid atop the bones of Tenochtitlan.

Heading towards what is still the beating heart of Mexico City.

Ahead lies the Catedral Metropolitana with the Zocalo and Palacio Nacional to the upper right of the 2020 image.

Top image 1940 : Bottom image 2024

The bottom image (below) shows the causeways that proved to be quite problematic for both the Spanish and the Mexica.

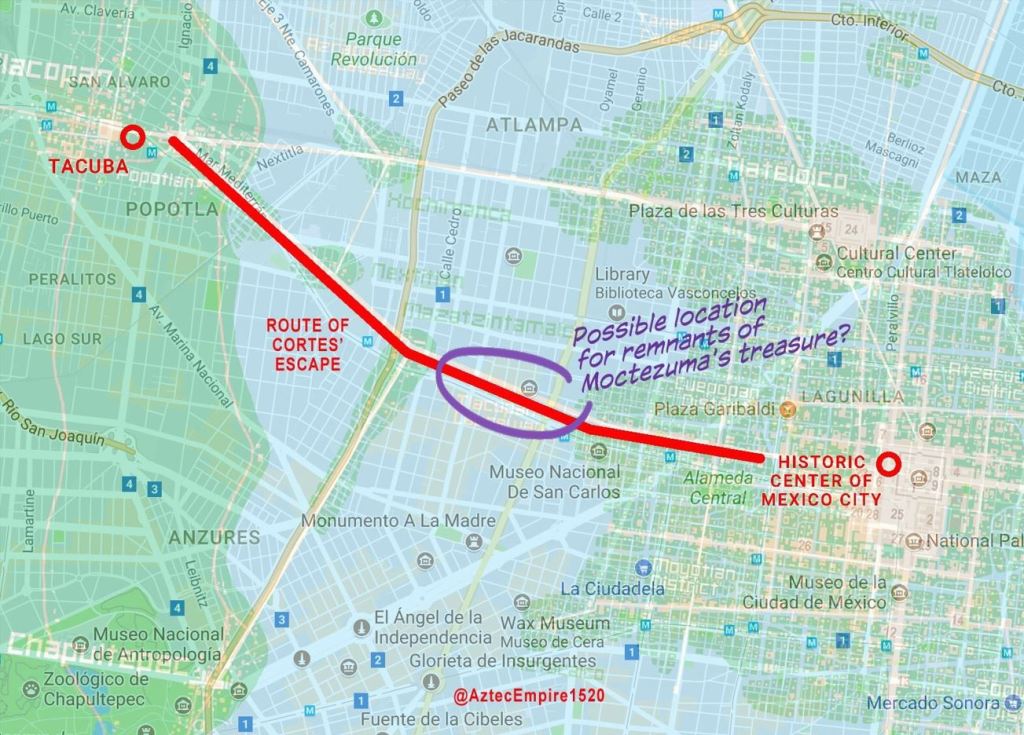

In March of 1981, during the construction of a bank just north of Alameda Central a construction worker found a 4.35 lb (just under 2kg) crudely made gold bar buried nearly 5 metres (15.7 feet) deep into the excavation. These bars were made from the melted down artefacts pillaged from the Mexica and were created so as to be more easily transportable than the artefacts themselves. This was a wholesale rape of the culture and an uncountable loss to all of humanity.

Some examples of Mesoamerican goldwork artisanship

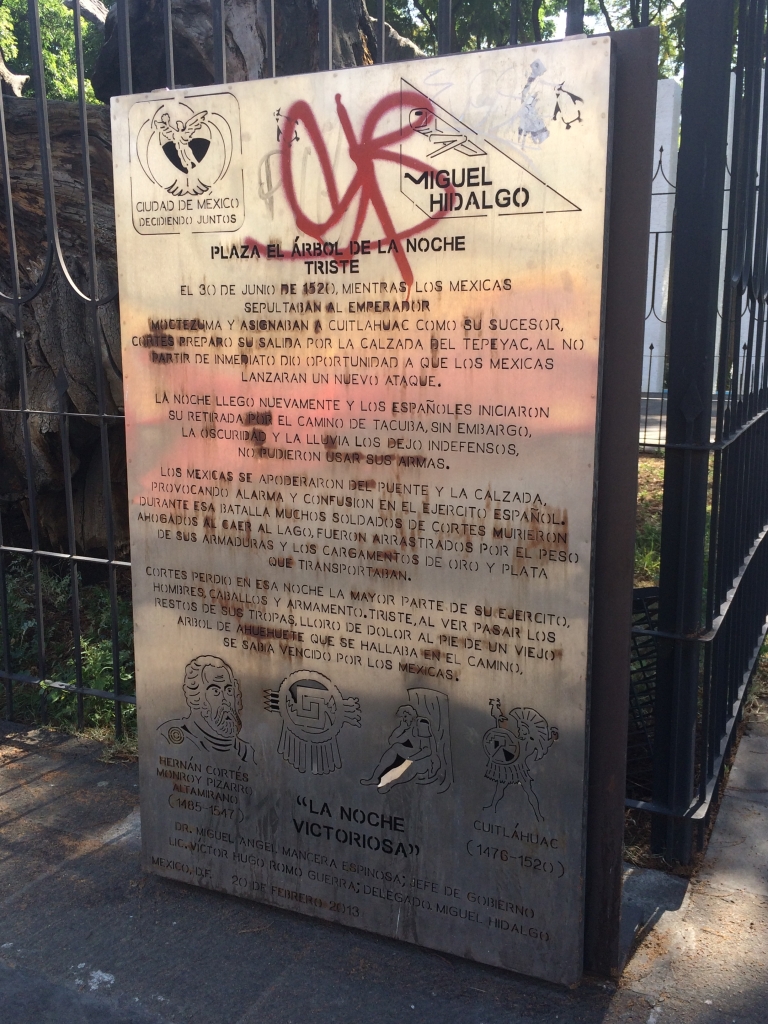

The gold bar previously depicted was one of the spoils of war that the Spaniards lost during La Noche Triste.

In May 1520 Cortés left Tenochtitlan to address the issue of his position being usurped by a group sent by Governor Velázquez of Cuba who had been sent to arrest Cortés for insubordination. Cortés left Tenochtitlan in the care of a trusted lieutenant, Pedro de Alvarado, while he marched to the coast to deal with the interlopers. This proved to be a bad decision.

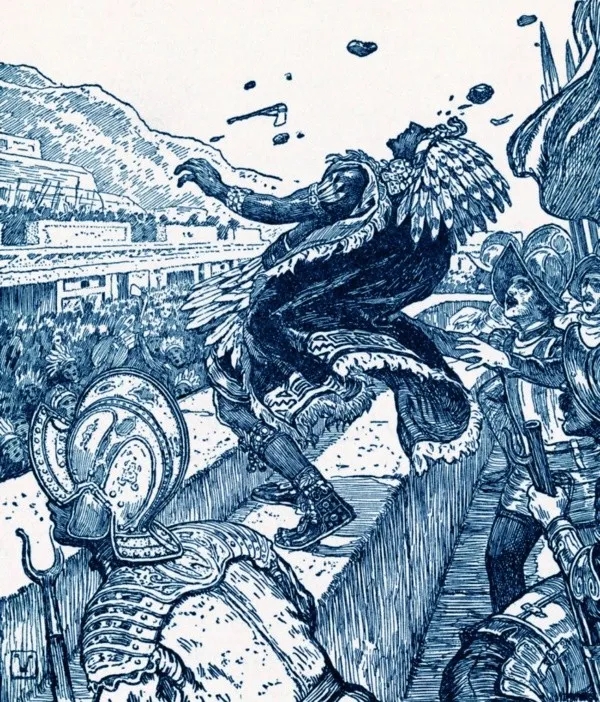

During Cortés’s absence, Alvarado oversaw a slaughter of Aztec nobles and priests celebrating a festival in the city’s main temple because he misunderstood the event and feared the celebrants were fomenting revolution. In retaliation, the Aztecs laid siege to the Spanish compound, in which the current Tlatoani (ruler) Moctezuma was being held captive. By the time Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan in late June, the Mexica had lost faith in Moctezuma and had elected a new Tlatoani named Cuitláhuac.

Cortés ordered Moctezuma to address his people from a terrace in order to persuade them to stop fighting and to allow the Spaniards to leave the city in peace. The Aztecs, however, jeered at Moctezuma, and pelted him with stones and darts. In the ensuing fracas Moctezuma was struck in the head and died. The Spaniards claimed it was a Mexica thrown missile that laid flat Moctezuma but the Mexicans themselves claim this to be filthy Spanish propaganda and that it was the Spanish who killed him as he had lost any bargaining power he might have still had (perhaps we’ll never know).

On the night of July 1, 1520, Cortez’s and his men fled their compound and headed west, toward the Tlacopan causeway. The causeway was apparently unguarded so the Spaniards made their way out of their complex unnoticed, winding their way through the sleeping city under the cover of a rainstorm.

They were soon noticed however and the alarm was raised. Numerous warriors, noblemen and commoners alike, emerged from their houses and began attacking the Spaniards from every direction. The fighting was ferocious. The Spaniards fought their way across the causeway but the men were weighed down with looted gold and many fell into the water and drowned. This was Cortés greatest loss during his time in Mexico.

Sources are not in agreement as to the total number of casualties suffered by the expedition. Cortés himself claimed that 154 Spaniards (1), forty-five horses, and over 2,000 native (Tlaxcallan) allies were killed (2) including Moctezuma’s son and daughter.

- although other claims reduce this number to 15 (which I think an unlikely low figure) and others claim between 600 or more than 1000 Spaniards were slain (I think these numbers likely to be too high). Regardless of the numbers, Cortés had his arse handed to him on that night in 1520.

- this number rises to 4000 in some estimates

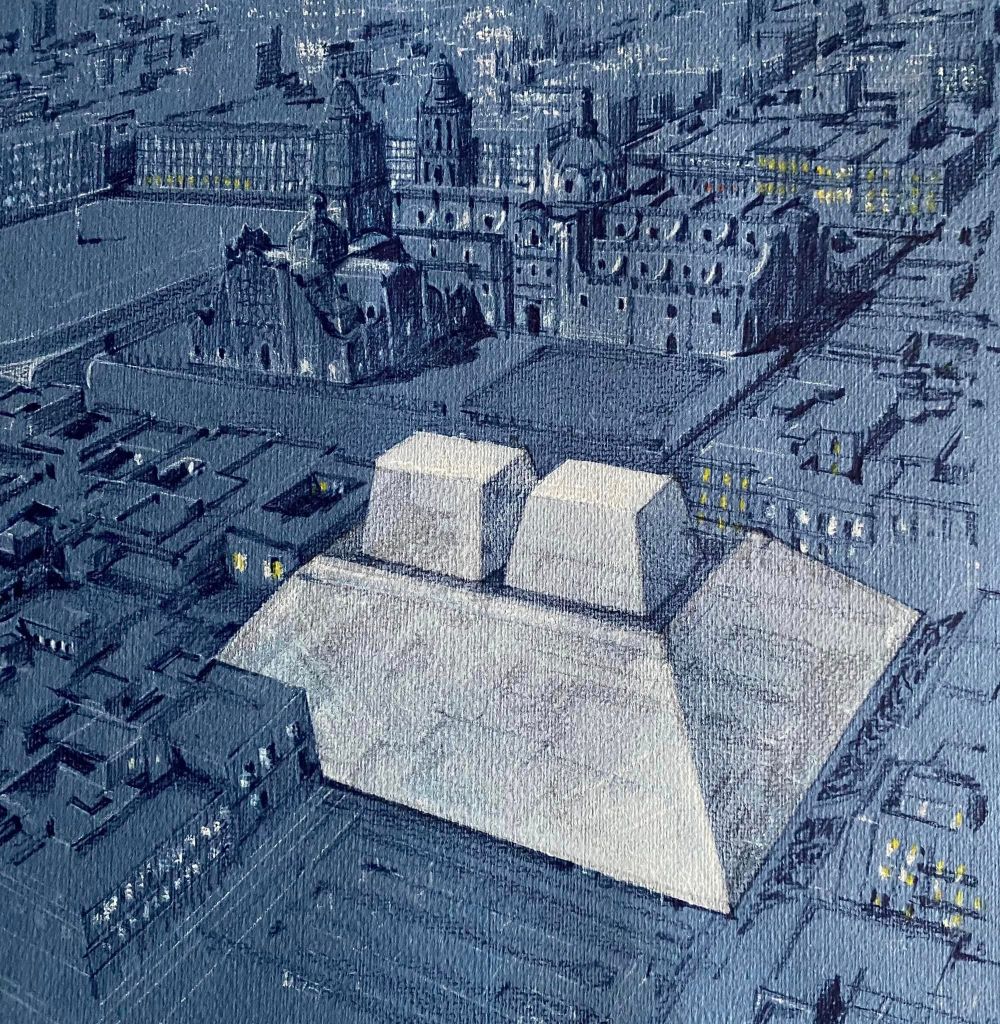

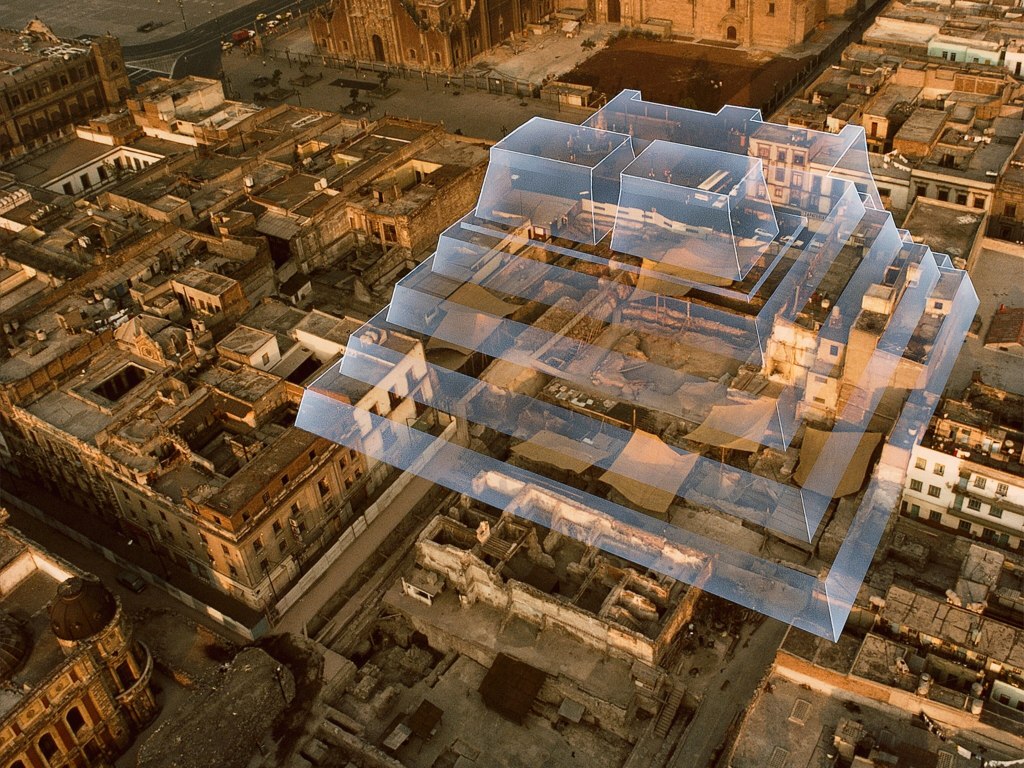

The Templo Mayor

The Templo Major lay at the very heart of Tenochtitlan. At its peak lay two temples used to worship their major Gods. Huitzilopochtli (the God of War and the Sun – their primary God) and Tlaloc (the God of water). These two forces, warfare and water were the very bread and butter of the Mexica civilisation.

Excavations of the Templo have been ongoing and have progressed much further than my visit in 2007 (images above).

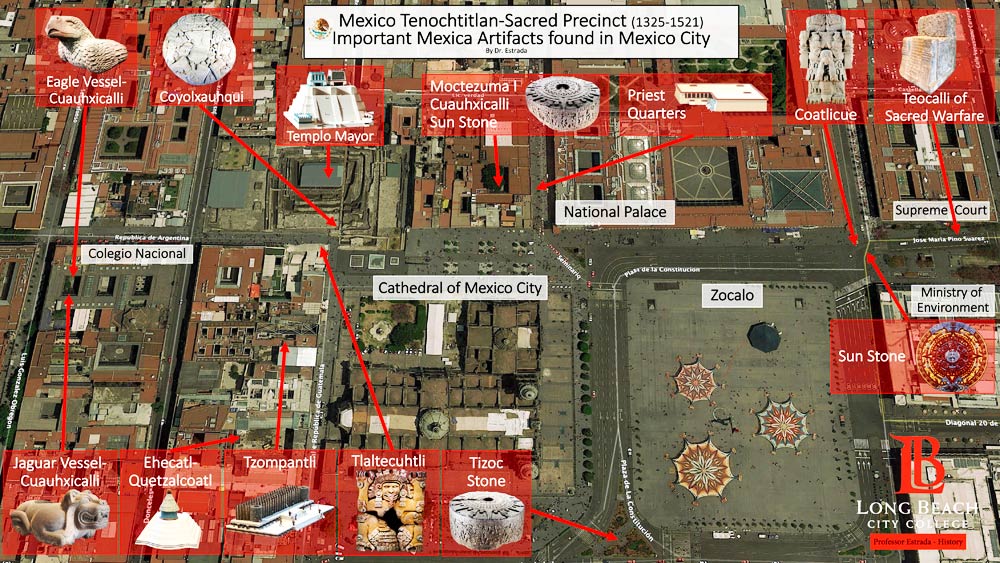

This is where the temples stood in relation to the city as it is now.

So much (and so little) appears to have changed.

Archaeologically (and somewhat literally) the City is a gold mine

1790 was a big year for discoveries. Excavations in and around the Plaza de la Constitución (Zocalo) in México City uncovered several artefacts.

Towards the end of the 18th century, the viceroy Juan Vicente de Güemes initiated a series of urban reforms in the capital of New Spain. One of them was the construction of new streets and the improvement of parts of the city, through the introduction of drains and sidewalks. In the case of the then called Plaza Mayor, sewers were built, the ground was levelled and areas were remodelled.

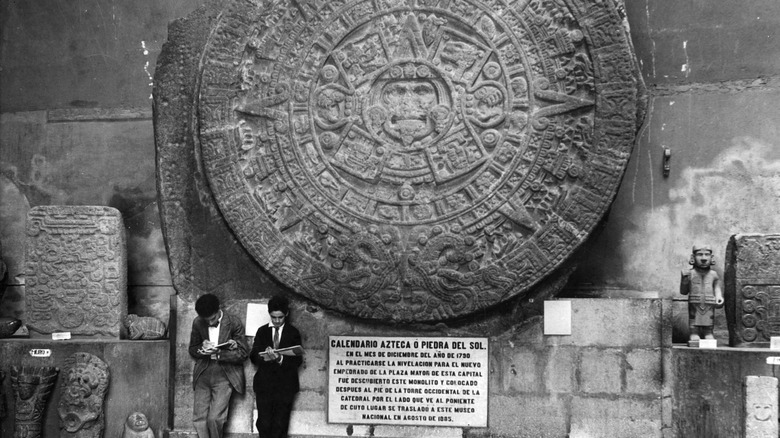

The Sun Stone

José Damián Ortiz de Castro, the architect overseeing the public works, reported the finding of the sun stone on 17 December 1790. The monolith was found half a yard (about 40 centimetres) under the ground surface and 60 metres to the west of the second door of the Viceregal Palace (now called the Palacio Nacional)

The stone was initially displayed outside, attached to the wall of the Catedral Metropolitan. You can see it in the above image on the lower left corner of the building. It has long since been moved to the Museo Nacional de Antropologia and is well worth a visit.

Current Mexican coinage has been cleverly designed to emulate the Sun Stone. The outer ring of each different denomination of coin contains one of the rings of the stone with the face of Tonatiuh (an aspect of the sun god) placed centrally in the 10 peso coin.

The central face and the surrounding design of the Sun Stone represent the Aztec glyphs for the five successive creation eras of the terrestrial world, from the earliest to the present. The first creation, or Sun, as the Aztecs called them, is shown in the box to the upper right of the central face, and was named Nahui Ocelotl, 4 Jaguar, for the day in the Aztec 260 day calendar on which it ended. Continuing counter clockwise, with the upper left box, the next creation was Nahui Ehecatl, or 4 Wind. Then at lower left, Nahui Quiahuitl, 4 Rain, and at lower right, Nahui Atl, or 4 Water. The Jaguar Sun was destroyed by giant jaguars; the Wind Sun by terrible hurricanes; the Rain Sun by a rain of fire; and the Water Sun by a great flood. Tonatiuh himself represents the 5th and current era. This fifth sun is characterized by the day sign Ollin, which means movement. According to Aztec beliefs, this indicates that this world will come to an end through earthquakes, and all the people will be eaten by sky monsters (probably Iztpapalotl’s tzitzimime)

Eeek

Piedra de Tizoc

The Tizoc Stone was (re)discovered on 17 December 1791 when the Zócalo, the heart of downtown Mexico City, was being repaved. Workmen had been cutting cobblestone, and were about to cut up the carved monolith. A churchman named Gamboa happened to be passing by and saved the stone from the same result.

Coatlicue

This statue was found on the south east edge of the Plaza Mayor in Mexico City in the course of reconstruction and drainage work in the Plaza Mayor in 1790 but was thought so terrifying that it was immediately reburied.

The figure is 3.5 m high, 1.5 m broad and depicts the goddess Coatlicue in her most terrible form with a severed head replaced by two coral snakes, representing flowing blood. She wears a necklace of severed human hands and hearts with a large skull pendant. She also wears her typical skirt of entwined snakes whilst her hands and feet have the large claws which she uses to rip up human corpses before she eats them

El Teocalli de la Guerra Sagrada – The Teocalli of the Sacred War

The sculpture was first discovered in 1831 in the foundations of the National Palace of Mexico, but was not removed until the 1920s. It is now located in the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico City. The teocalli (1) celebrates the triumph of the sun in the universe and affirms the power of the Mexica after the founding of their city in the year 2-House (1325), the date inscribed on the top of the monolith.

- variously referred to as the Monument of Sacred War, the Teocalli of Sacred War, the Temple Stone or, more simply, the throne of Motecuhzoma II (Montezuma)

Coyolxauhqui

On February 21, 1978, a group of electric-power company workers digging to install underground transformers in downtown the Mexico City came across a large shield-shaped stone covered in reliefs while digging.

The discovery of the Coyolxāuhqui stone led to a large-scale excavation, directed by Eduardo Matos Moctezuma, to unearth the Huēyi Teōcalli (Templo Mayor)

They do like to put their history on their money, but hey, don’t we all?

This is one of my faves

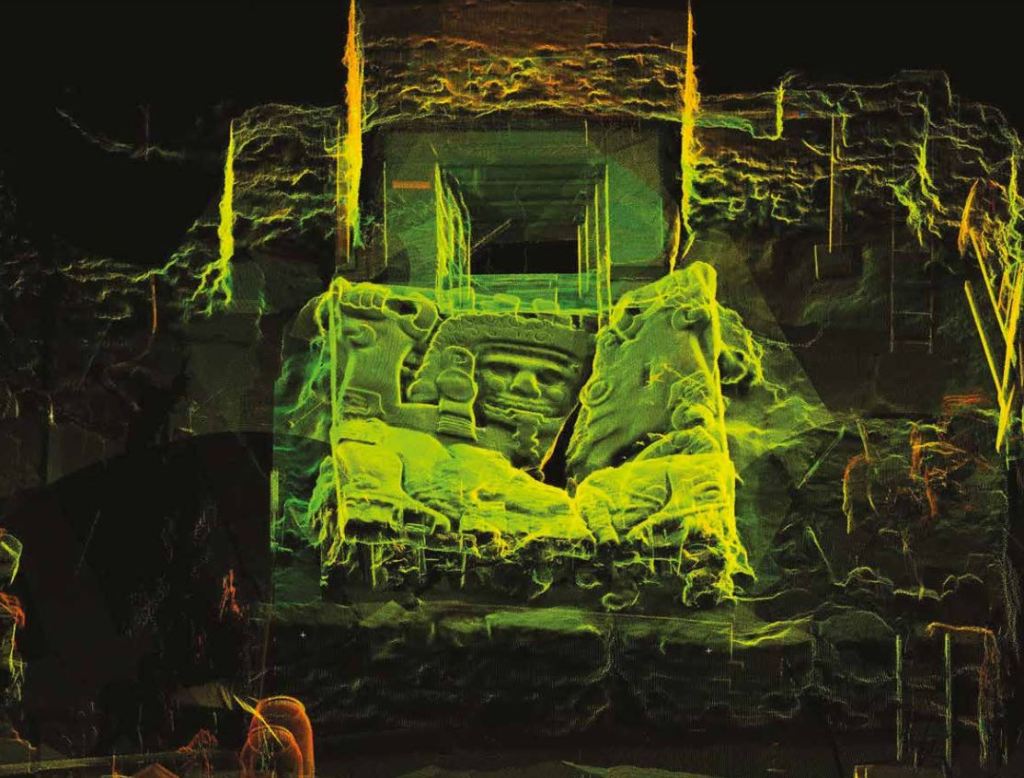

Tlaltecuhtli

In 2006, a massive monolith of Tlaltecuhtli was discovered in an excavation at the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City)

In May 2008 a team of researchers forming part of the Templo Mayor project discovered a large offering which had been placed underneath an enormous statue of the goddess Tlaltecuhtli

Offering 126, the largest found so far at the Templo Mayor, is composed of almost 4,000 organic remains, of which three-fourths (3,045) are marine molluscs. This material has been analysed by biologist Belem Zúñiga Arellano, a researcher at the National Institute of anthropology and history (INAH), who identified 111 species with 40 of them coming from the Atlantic, 66 from the Pacific, three found on both coasts and two from rivers. Significantly, 40 species come from an area which includes the Gulf of Mexico, Florida, the West Indies, the Caribbean Sea, Venezuela and Brazil, and 66 from Baja California to Ecuador. “This preponderance of species suggests on the one hand an expansion of the Aztec Empire during the reign of Ahuizotl, when he conquered populations of the Pacific coast, in the current states of Guerrero and Oaxaca. On the other hand, it also refers to trade relations with populations established to the south and the Caribbean“, said Zúñiga Arellano

Archaeologists Alejandra Aguirre Molina and Antonio Marín Calvo, working under the direction of Juan Ruiz Hernández of the Proyecto Templo Mayor uncovered (offering 186) a stone chest filled with objects from the sea and 15 anthropomorphic sculptures in green stone, dating from the reign of Moctezuma Ilhuicamina (1440–69). In addition to the sculptures, offering 186 included two earrings in the shape of rattlesnakes and a total of 137 beads made of various green stones, accompanied by sand and 1,942 different elements from the ocean including shells, snails, and corals.

Águila Cuauhxicalli – Cuauhxicalli Eagle Bowl

This piece was found in 1985 in the Templo Mayor sacred precinct. This sculpture depicts a golden eagle, poised ready to attack. The bowl on its back identifies the object as a cuauhxicalli or ‘eagle vessel’, a container used for sacrificial offerings.

Templos de Ehecatl

A temple to the wind god Ehecatl (an aspect of Quetzalcoatl) was uncovered during the excavations for the building of the Pino Suarez metro station 1967. It was restored somewhat and is now able to be viewed from both above and below the ground. The Mexico City Metro system is filled with enough sites to keep even the fussiest tourist occupied for a week or so.

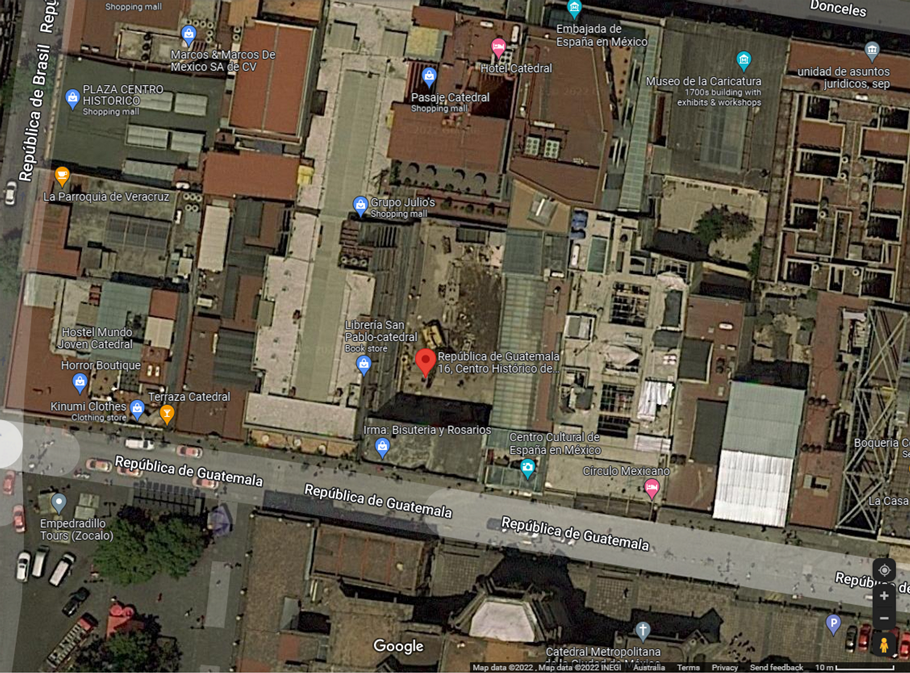

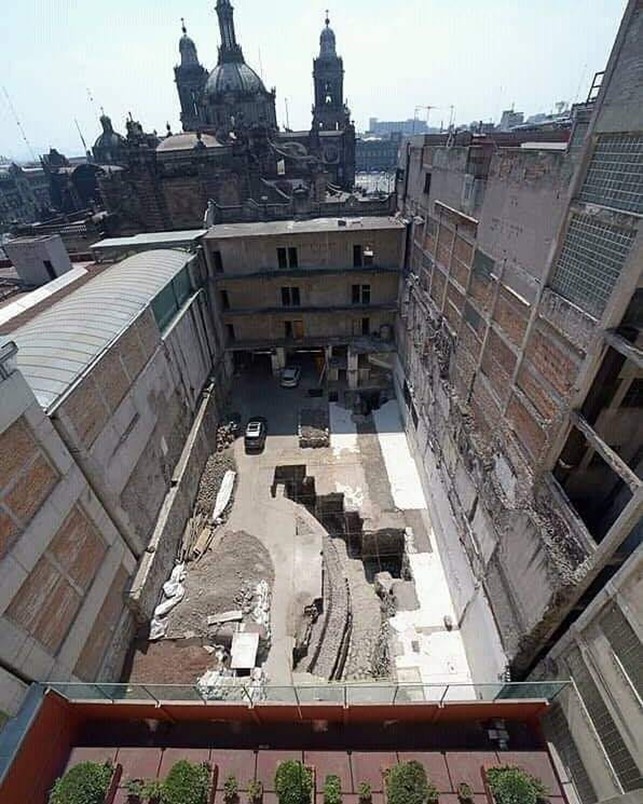

During my visit I stayed at the Hotel Catedral located just behind the Catedral Metropolitan and my hotel room overlooked the back of the façade of a building that had no doubt been retained due to its historical value.

Excavations have since uncovered another temple to the wind god Ehecatl below the surface of the empty space between the two buildings.

My guess is that if you picked a spot anywhere in Mexico City and started digging you would be more than likely to uncover relics of the past.

Tenochtitlan was built on a lake though so maybe not “anywhere” would work, although, as I’ve noted, Cortes and his men did drop a lot of shit as they were fleeing on that rainy night.

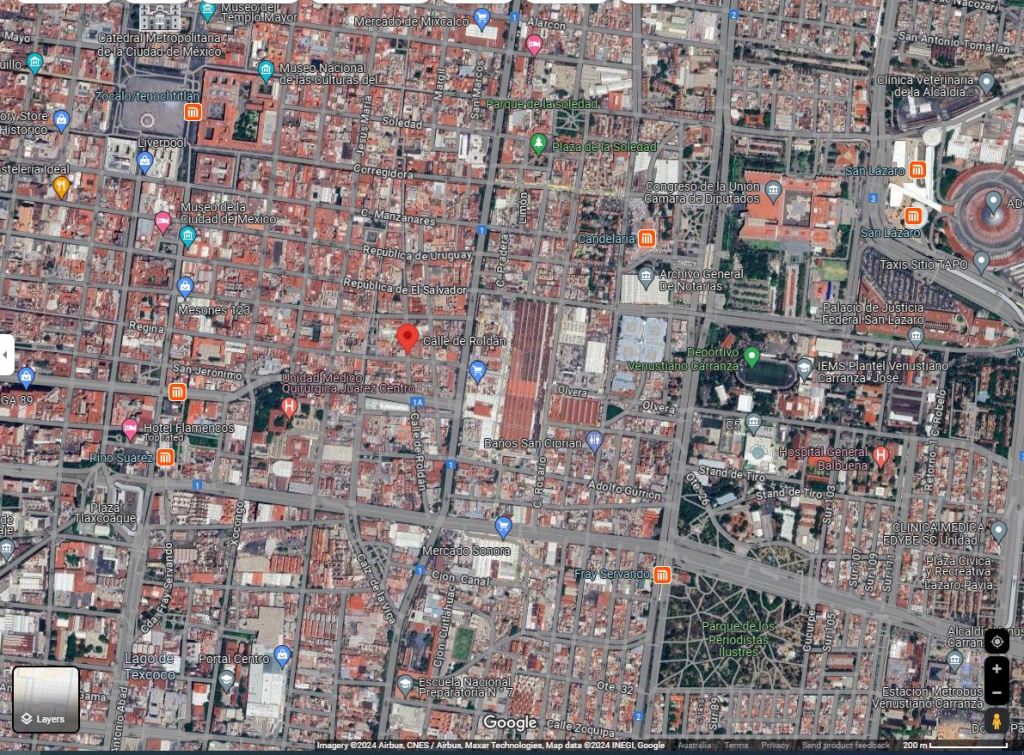

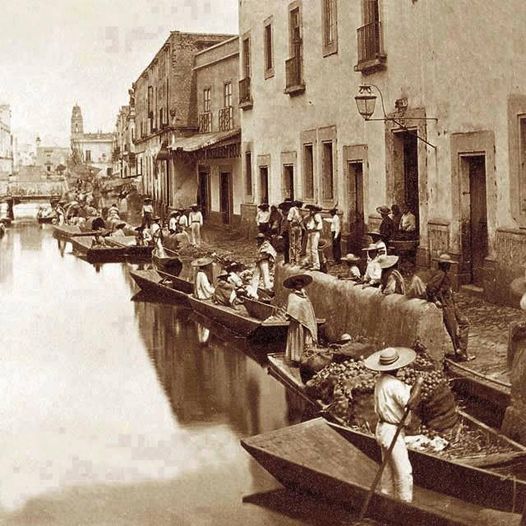

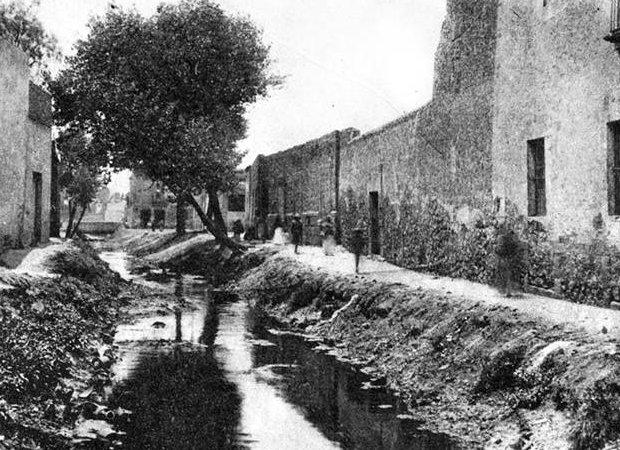

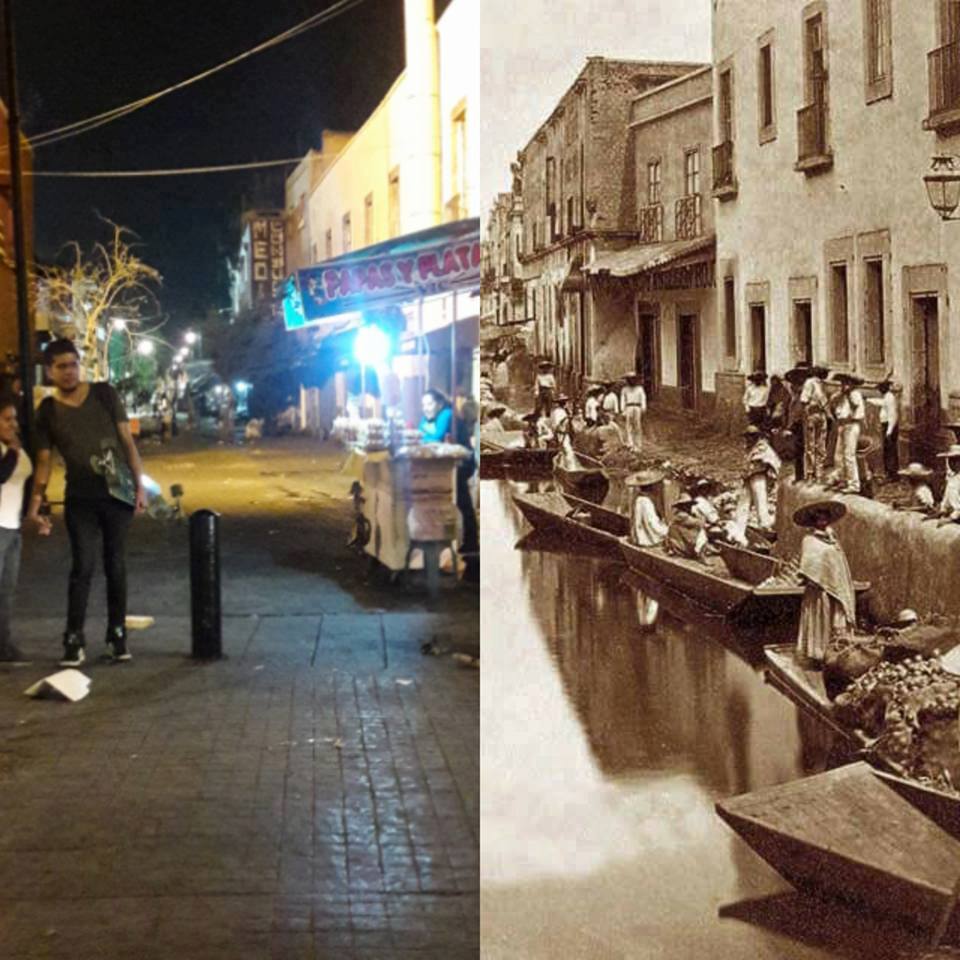

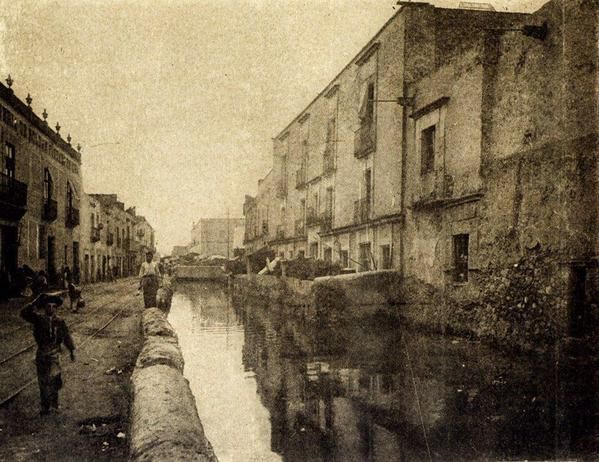

Tenochtitlan was serviced primarily by water. There were several causeways connecting the island to the mainland but the city was primarily an aquatic one.

The remnants of these canals still exist under the streets of the CDMX

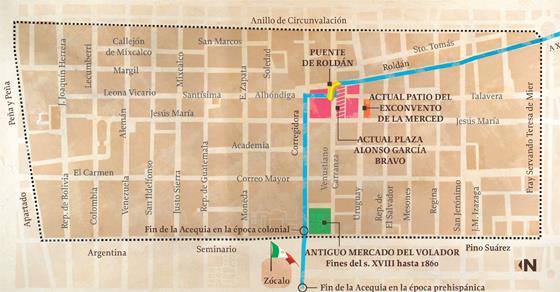

Roldán Street is one of the oldest streets in Mexico City, and is located in the La Merced neighborhood, in the historic centre of the city.

Remnants of these original waterways still exist today in the region known as Xochimilco.

They are still used as they originally were. Although largely a tourist area (and very popular with residents of México City as a weekend get away) market gardens and housing still exists. The area was once quite polluted but this has been turned around by environmental activism and the proud local population.

References

- Biar, Alexandra. (2020). A Lacustrine Cultural Landscape in the Prehispanic Basin of Mexico. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 49. 341-356. 10.1111/1095-9270.12424.

- Biar, Alexandra. (2021). Navigation paths and urbanism in the Basin of Mexico before the Conquest. Ancient Mesoamerica. 34. 1-20. 10.1017/S0956536121000328.

- Chavero, Alfredo (1876). “Calendario Azteca: un ensayo arqueológico” (PDF). Imprenta de Jens y Zapiaine.

- Hassig, Ross. (1994) Mexico and the Spanish Conquest. New York: Longman

- López-López Eugenia, Heck Volker, Sedeño-Díaz Jacinto Elías, Gröger Martin, Rodríguez-Romero Alexis Joseph (2023) A comparing vision of the lakes of the basin of Mexico: from the first physicochemical evaluation of Alexander von Humboldt to the current condition : Frontiers of Environmental Science; Vol 11 July 2023 : https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1217343

- López Luján, Leonardo (2006). “El adiós y triste queja del gran Calendario Azteca” (PDF). Arqueología Mexicana 78. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- MATOS MOCTEZUMA, EDUARDO (December 1985). “Archaeology & Symbolism in Aztec Mexico: The Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan”. Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 53 (4): 797–813. doi:10.1093/jaarel/liii.4.797.

- Read KA. 1986. The Fleeting Moment: Cosmogony, Eschatology, and Ethics in Aztec Religion and Society. The Journal of Religious Ethics 14(1):113-138.

- Rocha, María. (2012). El relieve monumental de la diosa Tlaltecuhtli del Templo Mayor: estudio para la estabilización de su policromía. Intervención Revista Internacional de Conservación Restauración y Museología. 3. 23-33. 10.30763/Intervencion.2012.5.60

- F., Townsend, Richard (1997). State and cosmos in the art of Tenochtitlan. Harvard University. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. (3rd impr ed.). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. ISBN 0884020835. OCLC 912811300.

Websites and Articles

- “Coatlicue, Historical and Chronogical Description of the Two Stones that were Discovered in Mexico City’s Main Plaza,” VistasGallery, accessed April 9, 2024, https://vistasgallery.ace.fordham.edu/items/show/1682.

- Tlaltecuhtli ; Offering to goddess reveals reach of late 15th century Aztec empire : http://www.pasthorizonspr.com/index.php/archives/01/2015/offering-to-goddess-reveals-reach-of-late-15th-century-aztec-empire?

- Dana Leibsohn and Barbara E. Mundy. (2015) Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820. http://www.fordham.edu/vistas.

- Losses on la Noche Triste – https://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/teaching-resources-for-historians/teaching-and-learning-in-the-digital-age/the-history-of-the-americas/the-conquest-of-mexico/letters-from-hernan-cortes/cortes-on-la-noche-triste-or-the-night-of-sorrows

Images and Mapas

- Aztec Suns – https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/calendar/calendar-stone

- El Teocalli de la Guerra Sagrada – By Wolfgang Sauber – Cropped from File:Teocalli.jpg., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6838207

- La Noche Triste maps via Aztec Empire Comics (Big Red Hair) : https://twitter.com/AztecEmpire1520/status/947610843570626561

- Lago Texcoco and Nezahualcoyotls Dyke : Tomás J. Filsinger 1985, 1992, 2012, 2018, 2021, ongoing. Maps of Tenochtitlan

- Plaza of the Tree of the Night of Sorrows Marker : https://www.hmdb.org/PhotoFullSize.asp?PhotoID=382772

- Tlaltecuhtli – By Chaccard – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47172137