I have previously written of the mythology (1) of various Aztec deities (2) and even the origin of the word Aztec or if there was even a people known as the Aztecs (3). I recently came across a video regarding Dia de muertos (4) that has convoluted the issue even more. It seems that even amongst those knowledgeable of such things there is even more confusion.

- (from the Greek mythos for story-of-the-people, and logos for word or speech, the spoken story of a people) is the study and interpretation of often sacred tales or fables of a culture known as myths or the collection of such stories which deal with various aspects of the human condition: good and evil; the meaning of suffering; human origins; the origin of place-names, animals, cultural values, and traditions; the meaning of life and death; the afterlife; and the gods or a god. Myths express the beliefs and values about these subjects held by a certain culture.

- See Posts Xochipilli. The Prince of Flowers; Mayahuel and the Cenzton Totochtin; Huitzilopochtli, Tenochtitlan and the Opuntia Cactus

- See Post Origins of the words Aztec and Mexico

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LPonoFDbqJg

Please take into account that in this Post I am only referring to two teachers of esoteric Mexican knowledge, Laura Gonzalez (1) and Sergio Magana (Ocelocoyotl) (2) and that this only presents an extremely small fraction of this occulted (3) knowledge.

- tarot reader, witch for hire, ordained Priestess of the Goddess by Fraternidad de la Diosa – Templo de la Diosa, minister in training, practitioner of traditional Mexican folk magic, and self-proclaimed expert on dia de muertos.

- mystic, healer, and teacher of the Nahuatl tradition. He has been initiated into the 5,000-year-old lineage of Mesoamerica as well as the Toltec dreaming oral tradition. The part of this knowledge in which he has specialized, is the one known as Toltecayotl (the knowledge of wise men) that encompasses Nahualism: the teachings imparted to rulers, warriors and priests on how to control reality through dreams, a deep exploration of what we nowadays call the unconscious, to overcome all of our weaknesses and become the best possible version of ourselves. It also encompasses dream states, which are altered states that combine being asleep and being awake and allow us to see into other energetic dimensions.

- occulted simply means hidden from view. There is NO satanic or evil connotations to the use of this word.

The first conundrum is “Were there a people known as the Aztecs?”.

Although it is commonly believed that the Mexicans, prior to the arrival of the Spanish, were called Aztecs it is generally believed that there were no Aztec peoples as such but an Aztec empire. The word Aztec referred to an alliance of three groups known as the Triple Alliance (1) and the Aztec language (2) was a lingua franca (3) or in essence a “trade” language. Laura is adamant that there were no Aztec people and the peoples generally referred to as Aztec were the Mexica-Tenocha people. Sergios teachings however speak to the opposite of this (4).

- The Triple Alliance was an alliance of three Nahua altepetl city-states: Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan.

- Nahuatl

- a language that is adopted as a common language between speakers whose native languages are different.

- The Aztec people, named after their birthplace Aztlán, already existed and that an omen, triggered by a hummingbird landing on a tree which then split, signalled that one particular group should separate from a group of seven tribes that coexisted together. This group were to let go of the name Aztec and call themselves the Mexicah. The story then joins the commonly known version (eagle eating a snake whilst perched on a cactus) and the empire consequently created by the wandering Mexicah tribe was called the Aztec empire because it contained many peoples from the other tribes that originally hailed from Aztlán. See Post Origins of the words Aztec and Mexico

One of the origin myths of the Aztecah (1) was that there were seven tribes (2) living in a place consisting of seven caves called Chicomoztoc. Each cave housing one of the seven tribal groups. If, as I will discuss shortly, there were no Mesoamerican deities but that each of these characters is representative of an esoteric or occulted concept then perhaps this origin myth is too. Sergio refers to the unconscious to be understood as a cave. Perhaps these seven caves of Chicomoztoc are representative of seven levels of some deeper understanding. His work concentrates on the shamanic power of dreaming.

- the “people from Aztlán”. Aztlán is also referred to as a place that the Mexicah settled at after leaving Chicomoztoc.

- the Xochimilca, Tlahuica, Acolhua, Tlaxcalteca, Tepaneca, Chalca, and Aztec.

The next enigma involves a whole pantheon of deities.

Mexico was not one country at the time of Cortez’ incursion. It consisted of many indigenous groups with their own languages and belief systems which were all (more or less) held together under the oppressive hegemony of the Aztecs. Many of these peoples claimed descent from the Toltecs or Olmecs and, according to the Spanish chroniclers, worshipped an array of pagan gods. This is where, according to Laura, the problem arises. By the time the Spanish became interested in the belief systems of the peoples they were subjugating (1) they had killed all of the all of the wise people and those educated in certain matters (2), particularly the knowledge of religion (3). They (the Mexica-Tenocha) did not have a religion as much as they did a lifestyle or a philosophy of life. When the Mexica tried to explain these concepts to the colonisers (which was made more difficult because the colonisers had killed all the wise people and those educated in such matters) the explanations were delivered by those not truly able to elucidate the concepts and which were then viewed through the lens of the colonisers own belief systems and were warped by this. The colonisers anthropomorphized all these processes, these forces, these entities and, according to Laura, created gods where previously there were none. In Mexica concepts everything was sacred, was to be respected and had a reason to live. They did not have a concept of reincarnation as such but rather the concept that everything occurs in cycles. People who speak the language (4) do not ask “god” for a favour. There were no gods and goddesses but sacredness in everything. The gods never spoke back to the Mexica in their philosophy. “We did not believe in gods and goddesses. That is a colonisers concept not an Aztec concept (corrects herself) not a Mexica concept”. Noel (Glueck & Morales 2020) also speaks of this “The Nahuatlacah (5) did not actually have devils, “good” or “bad”; they had energies they revered and utilised. The Spanish, for lack of understanding and vocabulary, dubbed them as gods and demons”

- knowledge that they wanted so as to be able to dominate them more effectively.

- not to mention also burning their libraries. This is also evident in the construction of books/codices before and after the arrival of the Spanish. Mesoamerican codices used a variety of colourful locally produced inks. As the population dwindled through disease and genocide the knowledge of producing these dyes died out. This can be noticed in the codices as earlier ones contained many colours whilst the later ones soon became almost monochromatic.

- The definition of which can be taken as “the belief in and worship of a superhuman controlling power, especially a personal God or gods” or “a particular system of faith and worship”. The last definition doesn’t particularly have to involve a “god”.

- she did not mention which one but I assume Náhuatl (or perhaps she means the “coded” language of the idea itself)

- those who spoke Nahuatl.

Some of the misrepresented gods Laura spoke of were Tlaloc, Quetzalcoatl, Mictecacihuatl and Mictlantecuhtli.

Quetzalcoatl means “the beautiful vibration of life” Not the serpent god or the god of life.

Tlaloc was not the god of rain but the outcome of the process. The soaked land is Tlaloc. Perhaps petrichor is the breath of Tlaloc (authors fanciful imagination)

Another “god” that I tend to focus on is Xochipilli. This particular animus is not the God of intoxicating plants but rather representative of the Aztecs knowledge of the effects of plants on humans (Lozoya-Gloria 2003).

I will take some space here to look at the work of Patricia Granziera. In her work “Concept of the Garden in Pre-Hispanic Mexico” (2001) she elaborates somewhat on the spiritual beliefs in pre-hispanic Mesoamerica. It all (more or less) starts with Nanahuatzins sacrifice which initiated the creation of this world (1) part of this myth involves Nanahuatzins demand that the other gods present also sacrifice themselves so as to prevent the destruction of the earth that would result because of Nanahuatzins (the new sun) refusal to act appropriately and move across the sky as the sun is expected to do. The gods died as part of this process and as a result their divine essence (or soul) was present in all elements of creation. The very universe and all in it were imbued with this divine presence and were considered sacred. The cosmic forces of the universe, earth, water, wind and earthquake were seen as animate beings. Flowers, plants and trees were thought, like humans, to contain a soul and man was intimately connected to nature. For this reason, the deities were represented in anthropomorphic form as well as in the form of animals and flora. This reverence for nature was reported with “amazement” by the friars Motolinia, Bartolome de las Casas and Duran and could of course be nothing more than the work of Satan himself. This was no doubt exacerbated by the Spanish identifying these universal forces as gods in human form giving them further justification in their acts of genocide and destruction.

- known as the “Fifth Sun”

According to Laura, Mictecacihuatl and Mictlantecuhtli (1) are representative of the processes of our bodies at rest as the repair themselves. Mictlan is not a place but a state of resting. It is derived from the Aztec word micitli (2) which occurs in a state of extreme resting. Micitli (3) is to dream. Mictlan is to be in that moment of dreaming. REM (4) sleep is an example of us visiting Mictlan. Throughout your life you visit Mictlan may times (while you sleep). You visit (and come back from) Mictlan every time until the time you (ideally) die in your sleep (and do not return from Mictlan). These two gods are the anthropomorphisation of these concepts.

- the god and goddess of the underworld

- to dream

- My Nahuatl dictionaries notes the word “temictli” to mean dream (or illusion). In nahuatl te- and tla- are both non-specific object pronouns. Their contrast lies in whether the object of the verb is human or non-human: (te-chihua – he engenders someone) (tla-chihua – he does something, he makes something). So te-mictli = he engenders the state of dreaming (?)

- Rapid Eye Movement. This occurs during dreaming states, much like the twitching of a puppy dogs legs while it dreams.

Lauras explanation of the concepts of Mictlan are very interesting and they lead into something that Sergio teaches. “Energetically, the explanation of nahualism (1) is very simple. When we go to sleep, the tonal (2) and the nahual come together, forming a unique energy body. When this energy body is formed, we reach the state that in Náhuatl is known as temixoch (3), that is, a blossom dream, a lucid dream, controlled at will.” He goes on to say that “The etymological composition of Náhuatl hides a great part of the cosmology and mysteries of ancient Mexico. The words describe the creation process, the mathematical order of creation and the relationship between humanity and the cosmos, not only on a physical level but on an energetic level, too” (4). Sergio also teaches that learning how to sleep is to learn how to die.

- “To understand what nahualism is we must first understand what the word nahual means. It comes from the Náhuatl language and refers to an ancient body of knowledge that according to oral tradition originated with the Olmecs, the Chichimecas and the Teotihuacans. It was then continued by the Xochicalcas and passed to the Toltecs, before finally reaching the Aztecs and their main indigenous group, the Mexihcas”. The word nahual (or nagual) is also used to refer to someone with the ability to transform into an animal. Although not specifically good or evil these beings are generally feared.

- The tonal and the nahual are two of the energetic bodies that form our aura (or “egg”). The tonal is (more or less) equivalent to our waking mind. It surrounds our head while we are awake. The nahual is an energetic body that we use at death or to sleep. It resides in the navel area while we are awake. These two exchange positions when we sleep. This is a VERY simple explanation of a larger concept.

- Temixoch is noted by authors Hofman and Schultes as a state of hallucination triggered by the use of hallucinogenic plants.

- This is quite similar to the Jewish use of gematria where not only does a letter/word/sentence/phrase have a numerical or formulaic value it is in essence a code that speaks deeper meaning to those who can understand it.

Temixoch is a concept I would like to examine. Sergio describes it as a state of lucid dreaming, or to use a floral metaphor, a blossom dream. It is this state (1) and its connection to Xochipilli that interests me. If Xochipilli is not a god but a concept then what is that concept? That sacred, hidden meaning of life? Schultes and Hofman (1992) identify Xochipilli as the god of flowers (2) and describe temixoch as an inebriated state of ecstasy known as “the flowery dream”.

- The second level of Temictzacoalli (the Toltec Pyramid of Dreams). We can also attain this state while awake, by altering our state of consciousness, bringing the tonal (waking state) and the nahual (sleep/dream state) together in what we call daydreaming or dreaming while awake. This allows us to see a different reality – energy, ancestors, guides, the underworld and the future – either in the obsidian mirror or on the face of other people or somewhere else.

- or “plants that intoxicate”

The 9 Levels of Temictzacoalli : The Toltec Pyramid of Dreams

temictli = dream : tzacualli (tzacoalli) = pyramid

- Temictli (the lowest level) : the unconscious dream, the indomitable nagual, the dream that repeats our past in Mictlán over and over again and creates the invisible prison of the moon.

- Temixoch : the first step on the path of conscious dreaming and the place where all the great lucid dreamers of today are found. This kind of dream allows us to create our life. It is a step to cure a disease, generate abundance, have prophetic dreams.

- Yeyellin and Pipitlin : Considered one of the most difficult levels of the pyramid. In it we begin to explore our underworlds, the places where our mind is trapped. The yeyellis are energy beings that feed on negative emotions both the dream state as the waking. The pipitlin are energy beings that support and encourage us to develop our positive qualities like love, heroism and compassion.

- Tlatlauhqui Temictli : (tlatlauhqui = red : temictli = dream) : the sacred place of dreams that appear in red, although they are not normally this colour. They are the dreams that bring us memories of when we were in the womb. This level of sleep can heal and regenerate our body.

- Acatl : This level consists of accessing collective dreams, where the creations of all beings and everything are found. At this level we cannot move in our human form, but it is possible to do so in the form of much more advanced naguals such as rain and wind. At this point we are faced with one of the most difficult dilemmas to solve: the use that we will give to this kind of knowledge, which tests our character and our emotional control.

- Tecpatl : (tecpatl = flint. or obsidian knife) : This level is governed by the dream of the stones and feeds on the energy of the lower levels, which is why it was said that we were created from mud and we were the dream of the mineral kingdom, a consciousness deeper than our own. In the nagual it is the mineral level that feeds on the energy of the lower levels

- Tocatl : (tocatl = spider) : the spider that weaves the collective dreams, the one that unites the destinies in the dream state, the one that takes charge of all the connections, the one that weaves the dreamer with the dream that he will experience later.

- Alebrijes : They are Mexican handcrafted figures of bright colors that represent hybrid figures of different mixed species of animals. They are the only thing that remains of the ancient knowledge of the eighth level of dreams. They were created by the ancient naguals to protect what is most precious to them: the ninth level. To reach this level we have to go with a dream partner to a shared dream and avoid alebrijes, since these figures will challenge, question and even destroy the dreamers in the penultimate test of the nagual path.

- Cochitzinco : It means “the sacred place of sleep”, the place of darkness from where light emerges. It is a place where there are no dreams, only darkness in movement. In it we access the mind of Centeotl , the Black Eagle, the place of the original plan. This last test is related to power and ego. Here we have the option of intervening or not in the original plan. What we choose to do will depend on whether we are a nagual or not, and whether we can transcend the light and darkness of the mind.

Another interesting deity conundrum is that of Xochipilli and Xochiquetzal. The link with Xochiquetzal is interesting as she has in various sources been described as Xochipilli’s wife/consort, child, sibling (sometimes a twin) and even the other half of one gender fluid being (1). Although both figures were revered and celebrated by the same peoples (and sometimes worshipped alongside each other) each of these deities were patrons of different aspects of daily life. Whilst both were associated with sexuality Xochiquetzal was representative of pregnancy, childbirth and non-procreative sex (2) whilst Xochipilli was responsible for the consequences of the excesses of this kind of behaviour. Taken in this light these two gods can be seen as representative of these primal forces rather than actual beings.

- for further information see Post Xochipilli and Homosexuality

- hey it can be fun too you know

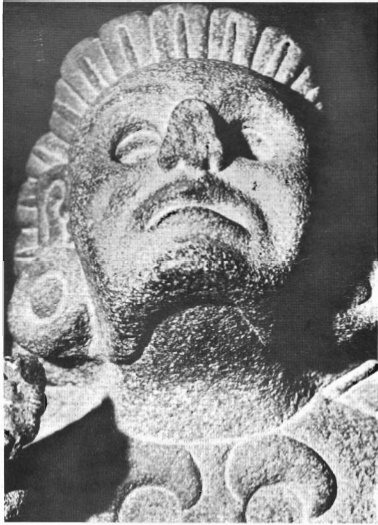

Xochipilli (left) and Xochiquetzal (right)

Xochiquetzal (left) and Xochipilli (right)

Another goddess I would like to briefly look at (only because she is one of my favourite children due to her connection to quelites) (1) is Quilaztli.

- See Post Papaloquelite : What’s in a name? In Nahuatl the word quilitl encompassed all green vegetables including the tendrils of squash vines, the leaves of larger shrubs such as Chaya and other plants now commonly referred to as weeds. Quelites, generally speaking, are edible herbs that have been wildcrafted or collected from cultivated fields. These plants may be harvested for their leaves, stems, roots, flowers or flower buds.

Quilaztli, one of the names of the mother goddess, is the special goddess of “those of Xochimilco” [at the south end of Lake Tetzcoco] (Gingerich 1988) (Duran 1971)(Motz 1997). Quilaztli was also known as a creation goddess. It was she who ground up the bones that Quetzalcoatl brought up from Mictlán, the world of the dead, and put them in a clay jar to create the humans of the Fifth Sun. She is a prominent avatar of Cihuacoatl and at various times announces herself as

- Cohuacihuatl – snake woman

- Cuauhcihuatl – eagle woman

- Yoacihuatl – warrior woman (or enemy woman)

- Tzitzimicihuatl – infernal woman (or demon woman)

In the chinampa regions Cihuacoatl was known as Quilaztli, the goddess from Colhuacan (Gómez-Cano 2010). Cihuacoatl is represented with the claws of a bird of prey and sometimes also with an eagle’s head or eagle’s wings. Eagle feathers may decorate her shield. These elements correspond to her other name: Quilaztli, which refers to an eagle. This is a reference to her nahual power: she can manifest herself (i.e. transform into) an eagle (Jansen 2017).

It is her name that is interesting to me when taken in light of the current conversation. Quilaztli is composed of “quilitl” (edible plant) and “–huaztli” (an instrumental suffix), the name meaning the instrument that generates plants. Taken in this context rather than being a goddess she is a generating force in general and is the force of nature responsible for the generation of green plants. She is also linked to pregnancy and childbirth (through being an aspect of Cihuacoatl) which is also another generating force of life.

This places her squarely in the Mesoamerican philosophies as a “force” rather than a “being” and certainly adds credence to the belief system as it existed before it was corrupted by the genocidal leanings of the Spanish.

All of the information I have presented above is, as I may have mentioned, only a small fraction of a very particular form of knowledge. It is also potentially problematic as it is derived from adherents who are the recipients of “oral tradition”. I must note that the veracity of secret knowledge that was passed down orally must be scrutinised profoundly. There are sources I have not relied upon such as the teachings of Carlos Castaneda (1) and another proponent of Toltec wisdom known as (amongst other names) Frank Diaz. These two authors have produced a lot of information on their various subjects but both have strong and vociferous detractors (of which there is not the space to go into here). I have only recently stumbled across the works of Frank Diaz and his Iglesia Tolteca (2) but almost at the same time I have come across reams of very negative information regarding this “church” and its founders (3). I make no comparisons between any of the people or institutions mentioned in this Post except to say that nothing should be accepted at face value and all ideas need to be researched thoroughly.

- I’m assuming that most readers will have heard of the anthropology student who was apprenticed to the Yaqui sorcerer Don Juan Matus

- Toltec Church

- I would like to point out that some of the allegations levelled at Diaz involve his support of cannabis and several slurs regarding him to be homosexual or queer (or the fact that they wear an earring or ponytail hair style) are periodically bought up. In my opinion none of these subjects warrant the denigration of a person. The allegations of his inability to understand Nahuatl and his tendency to create imaginary words, spellings and structuring of the language are valid arguments however. One of Franks collaborators, Julio Diana, is also attacked for a childhood trauma which resulted in some time being spent in a school for special needs children. All of these attacks are delivered by someone who appears to have a strong Christian orientation and they echo the standard Christian diatribe that resulted in the burning of heretics. You know the ones drug user, sodomite, Satan worship, burn the witch. However, the more I read about these characters I find myself having strong reservations about their particular form of esoterica.

References

- Carochi, Horacio (2001) Grammar of the Mexican Language, with an Explanation of its Adverbs (1645), trans. and ed. by James Lockhart, Stanford: Stanford University Press, pages 344–345, 372–373

- Durán, Diego, and Diego Durán. 1971. Book of the gods and rites and the ancient calendar. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Gibson, C. (1965). The Aztecs: The History of the Indies of New Spain. Fray Diego Durán. Translated, with notes, by Doris Heyden and Fernando Horcasitas. Introduction by Ignacio Bernal. Orion Press, New York, 1964.

- Gingerich, W. (1988). Three Nahuatl Hymns on the Mother Archetype: An Interpretive Commentary. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 4(2), 191-244. doi:10.2307/1051822

- Glueck, R and Morales, N. (2020) The Native Mexican Kitchen : A Journey Into Cuisine, Culture, and Mezcal : Skyhorse Publishing : ISBN10 1510745246

- Gómez-Cano, Grisel : The Return to Coatlicue: Goddesses and Warladies in Mexican Folklore : 2010 : Xlibris, Corp. : ISBN 1450091547

- Gonzalez, Laura : Mystic Chat Ep 20 Dia de Muertos 23/10/2020 : Last accessed 01/11/2020

- Granziera, Patrizia. “Concept of the Garden in Pre-Hispanic Mexico.” Garden History, vol. 29, no. 2, 2001, pp. 185–213. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1587370. Accessed 9 Nov. 2020.

- Herrera, Fermin . (2004) Nahuatl-English/English-Nahuatl Concise Dictionary (Hippocrene Concise Dictionary) ISBN-13 : 978-0781810111

- Jansen, M. E. R. G. N. (2017). Time and the Ancestors, chapter 6: Fifth Sun Rising. Maarten E.R.G.N. Jansen & Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez: Time and the Ancestors. Aztec and Mixtec Ritual Art (Brill, Leiden / Boston) . https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004340527

- Karttunen, Frances (1983) An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl, Austin: University of Texas Press, page 223

- Lozoya-Gloria, Edmundo (2003). [Recent Advances in Phytochemistry] Integrative Phytochemistry: from Ethnobotany to Molecular Ecology Volume 37 || Chapter twelve Xochipilli updated, terpenes from Mexican plants. , (), 285–311. doi:10.1016/S0079-9920(03)80027-8

- Magaña, Sergio (Ocelocoyotl) : 2012 – 2021 The Dawn of the Sixth Sun “The Path of Quetzalcoatl” : Blossoming Books : Edizioni Amrita srl : 2011

- Motz, Lotte : The Faces of the Goddess : 1997 : Oxford University Press : ISBN-10: 0195089677

- Schultes, RE + Hofman, A : Plants of the Gods : 1992 : ISBN 0-89281-406-3

- Sullivan, T. (1966). Pregnancy, childbirth, and the deification of the women who died in childbirth.