An interesting quelite has popped up in my feed. The flor de cimal. A reader (thank you Kellan) has asked about a (possible) quelite called flor de cimal and has noted the only reference to be found on this plant is “This small, red-leafed herb that grows at the base of the maguey – century plant – is incorporated into tamale dough in the traditional country cooking of the Sierra Oriental, whose indigenous population gathers and cooks with a wide variety of wild herbs.”

So, off to research I go.

**SPOILER ALERT**

Short Answer : I’m really not sure about this one.

Long Answer :

Spanning 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) the Sierra Madre Oriental runs from the Rio Grande on the border between Coahuila and Texas south through Nuevo León, southwest Tamaulipas, San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, and Hidalgo to northern Puebla

If we look at the maps above and follow the indigenous groups from North to South along the Sierra Madre Oriental we should note the number of groups (which would have been much higher prehispanically). This accounts for a huge amount indigenous knowledge of seasonally and locally available herbs and delicate annual plants (that would fall under the broad umbrella term of quelite)….and, if we take into account further divisions as indicated in the map below this number grows even further.

I could find no direct reference to this plant in any of my books on the herbs of México and the Americas either as a food or a medicine (1). It is likely that this plant falls into the category of quelite. Now if you don’t know what a quelite is then you’ve come to the right place and “Welcome to my Blog”. Quelites are my area of interest both as a chef and a naturopath. They are the wild herbs that pop up in cultivated areas such as milpas and coffee plantations. They are weeds that are carefully cared for as they are very useful plants and many are only seasonal wild plants (although some such as papalo and romeritos are cultivated commercially due to public demand). Check out my Post Quelites : Quilitl for further (generic) details and search my Blog for individual quelites (I do focus on the Porophyllum species in particular)

- When it comes to quelites my first references I usually lean on are the works of Diana Kennedy and the voluminous studies of Edelmira Linares and Robert Bye. Diana Kennedy is (or rather I should say was – she died 24 July 2022) a British writer who exhaustively researched Mexican cuisine long before it became cool to do so. She travelled extensively throughout Mexico cataloguing ingredients (many of them obscure or rare) and cooking techniques/recipes. She catalogued many recipes, the knowledge of which might be forever lost if not for her work. Linares and Bye are scholars from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and have produced a huge amount of work on the indigenous plants of the Americas covering culinary and medicinal uses, economic importance of the plants and the impact these plants had (and still have) on the cultures that utilise them (check out the References at the bottom for some of their work)

Some of the more commonly consumed quelites in Mexico. (click on images to enlarge)

The books have let me down so off to the interwebs I go.

One of the first online references to flor de cimal is in another Blog called MexConnect and an article penned by Karen Hursh Graber “A culinary guide to Mexican herbs: Las hierbas de cocina” notes…..”Flor de cimal: This small, red-leafed herb that grows at the base of the maguey – century plant – is incorporated into tamale dough in the traditional country cooking of the Sierra Oriental, whose indigenous population gathers and cooks with a wide variety of wild herbs”. This was written (or at least updated) in 1999 (the fact it notes it was updated points to an earlier publication date)

Malgorzata (2017) mentions the plant as being a herb used in Mexican food. ““Herbs used in Mexican foods include: acuyo or tlanepa, amaranth, anise, annatto, avocado leaf, balm-gentle, banana leaf, bay leaf, bean powder, chamomile, chaya, chepiche, chepil, chia, cilantro, cuajes, flor de cimal,……” (1)….and uses the following paper (Lee etal 2014) as its reference source….…where it is noted “In detail, Herbs used in Mexican foods are: acuyo or tlanepa, amaranth, anise, annatto, avocado leaf, balm-gentle, banana leaf, bay leaf, bean flower, chamomile, chaya, chepiche, chepil or chipil, chia, cilantro, cuajes, cumin, flor de cimal,….”(the list continues)(2)

- & (2) (the list in its entirety – exact same list in both documents) : acuyo or tlanepa, amaranth, anise, annatto, avocado leaf, balm-gentle, banana leaf, bay leaf, bean powder, chamomile, chaya, chepiche, chepil, chia, cilantro, cuajes, flor de cimal, halachas, hierbasanta, Indian paintbrush, lemon grass, lemon verbena, lenguitas, marjoram, Mexican safflower, oregano, pápalo, pepicha, peppermint, purslane, quintoniles, sesame, spearmint, sweet basil, Tilia, vervain, watercress, and wormseed

Karens Blog Post is at least 15 years older than any of the references in the studies. I wonder where she got the information from (and I wonder where they got it from as neither paper mentions Karen’s work). I have tried to contact Karen via her Blog to access her sources (if possible) but have had no luck contacting her.

Karens list in its entirety (the items in BOLD are foreign additions to Mexico’s culinary repertoire)…. This list, although broad is not comprehensive. It is a good list of the soft green herbs referred to as quilitl.

Achiote (annatto) Bixa orellana; Acuyo or tlanepa: Names used in Veracruz for hierba santa; Albahaca (sweet basil) Ocimum basilicum; Amaranto (amaranth) Amaranthus hypochondriachus; Ajonjolí (sesame) Sesamum indicum; Anís (anise) Pimpinella anisum; Azafrán (Mexican safflower) Cartamus tinctorius; Berros (watercress) Nasturtium officinalis; Chaya, also known as chayamansa, chayacol, and keki-chay, Cnidoscolus chayamansa; Chepil or chipil, Crotalaria longirostrata; Chepiche (Porophyllum species); Chía (chia) Salvia columbariae; Cilantro (coriander, Chinese parsley) Coriandum sativum; Cominos (cumin) Cuminum cyminum; Corteza de maguey or mixiote (century plant) Agave americana; Epazote (wormseed) Chenopodium ambrosioides; Flor de cimal; Flor de frijol (bean flower) Phaseolus vulgaris; Guajes (cuajes) hauxya; Halachas; Hierba buena (spearmint) Mentha spicata; Hierba de conejo (Indian paintbrush) Castilleja lanata; Hierba santa or hoja santa Piper auritum, Piper sanctum; Hoja de aguacate (avocado leaf) Persea americana; Hoja de maíz (corn husk) Zea maïs; Hoja de platano (banana leaf) Musa paradisiaca; Huazontle Chenopodium berlandieri; Laurel (bay leaf, bay laurel) Mexican: Litsea ssp, Mediterranean: Lauris nobilis; Lenguitas, orejas de diablo; Lipia (lemon verbena) Lippia citriodora; Manzanilla (chamomille) Matricaria recutita, Matricaria chamomilla; Mejorana (marjoram) Origanum majorana; Menta (peppermint) Menta piperita; Orégano (oregano) Origanum vulgare; Pápalo or papaloquelite Porophyllum ruderale spp macrocephalum; Pepicha or pipicha Porophyllum tagetoides; Perejil (parsley) Petroselinum crispum; Quelites (lamb’s quarter) Chenopodium berlandieri; Quintoniles (Amaranthus species); Romero (rosemary) Rosamarinus officinalis; Romerito Suaeda torreyana; Te limón (lemon grass) Cymbopogon citratus; Tila Tilia mexicana: Tomillo (thyme) Thymus vulgaris: Toronjil (balm-gentle) Agastache mexicana; Verbena Verbena officinalis; Verdolaga (purslane) Portulaca oleracea.

Etymology time. The first thing we look at is the word, the name of the thing. Language is usually structured to tell a story and if we breakdown the name of a thing there is often a great amount of information to be found. This is also particular of Nahuatl botany which had a precise naming system (which often provided a lot more information than our current Latin Binomial nomenclature system)

My Nahuatl dictionaries don’t have any entries for cimal but the do for cima and cimatl, which progress into cimapahtli

- cima.

Principal English Translation: to prepare the leaf of a maguey (agave) plant in order to extract the fiber

- cimatl.

Principal English Translation: a plant with an edible root, or the root

Frances Karttunen: CIMA-TL a plant (Desmodium amplifolium) the well-cooked root of which is used to season stews / cierta raiz de yerba

- cimapahtli.

Principal English Translation: medicinal plant of the bean family the root of which can be used to induce vomiting

The suffix -pahtli is an interesting one and denotes a herb with medicinal usage

- patli.

Principal English Translation: an herb or herbs with medicinal value; a great many herbs end in -patli or -pahtli, and some will have their own dictionary entries

Now none of this seems particularly helpful as it all seems to indicate a herb with emetic (1) properties. This is not unusual though as many plants may have edible foliage or flowers whilst the seeds and/or roots might not be edible (culinarily speaking)

- a medicine or other substance which causes vomiting.

Cima

The “cima” by itself is also quite interesting. From the point of view of this discussion it can not only refer to the “growing tips” of a plant and the trimming or removal of these growing tips but also the “swollen root” of a plant (which brings us back to cimatl)

- cima

variant spelling of CYMA

from Latin cyma young sprout of a cabbage, the tip of the stalk

- cima

See also: Cima, cimá and çima

Obsolete spelling of cyma [18th century]

Inherited from Latin cȳma, from Ancient Greek κῦμα (kûma).

From Old Galician-Portuguese cima, from Latin cȳma, from Ancient Greek κῦμα (kûma, “something swollen; wave, billow”), from κύω (kúō, “I am pregnant, conceive”). (referring to the swollen root perhaps?)

- cimá

second-person singular voseo imperative of cimar

- cimar

cimar (first-person singular present cimo, first-person singular preterite cimé, past participle cimado)

to crop; to cut shorter (removing the top)

Xiu-

I’m going to briefly take a sideways step here and look at “xiu” instead of “ci”. Now I know we’re wandering off path a little but I just want to investigate the “s” and “sh” sounds and how they relate (if they do at all)

- xiuh(mateca): to pull up plants, to clear ground

- xiuh(topehua): to remove weeds

- xiuh (iximatqui): an herbalist, one who works with herbs or greens

- xiuh(yo): something grassy, leaf

- xiuh(camotli): sweet potato greens

- xiuh(quilitl): a green herb

There is a definite plant/herb vibe to the xiuh and the last two examples play a part in what follows…..

Back to the cimatl

According to Lopez-Austin (1993) the word cimatl was a Nahuatl botanical term that “served to designate all plants that had a voluminous underground axis”

Dictionaries which explain Nahuatl glyphs go into a little more detail on cimatl

This (below) is either the edible root of an herb (cima(tl)] or the root of the medicinal plant called cimapatli (or cimapahtli), which has been abbreviated in the name. Perhaps these plants are one and the same.

This element (below) for what was originally thought to be a cimatl (an edible, medicinal root) has been carved from the compound glyph for the place name, Cimatlan. The predominant part of the place name refers to the medicinal plant. According to a presentation by Michel Oudijk (Library of Congress, 4/18/2023), the glyph for “cimatl” was misread by the person glossing it. Thus, the gloss refers to the camote, sweet potato, which is camo(tli) in Nahuatl. Knowing the Oaxaca context is essential for catching the error of the gloss, as Oudijk has explained.

The next one even comes with a botanical identification and makes an interesting connection to bean plants. Interesting in the fact that many species of frijole have edible leaves (although none with red leaves that I could find) and flowers.

CIMATL – Phaseolus coccineus L

Root which, when cooked well, is used to season stews.

Botany, Phaesolus coccineus L.

In the presentation of Chichimec foods.

• in īnelhuayo iuhquin cīmatl ic tomāhuac, cencah iztac , its root is like the one called cimatl, also big, it is very white. Describes the root of the huahuauhtzin plant

• cencah chichīc, huihhuiyac, iztac, mimiltotōntin, iuhquin cīmatl , very bitter, long, white, small and cylindrical like the cimatl root. Describes the roots of the cōztomatl plant.

• in īnelhuayo cōztic iuhquin cīmatl , its root is yellow like the one called cimatl.

Tucker & Janick link the cimapahtli (medicinal) to the cimaquilitl (edible – and maybe medicinal too)

cimaquilitl. in ixiuhyo itoca, cuahueco, tel no itoca cimaquilitl: . the name of its foliage is quaueco, but also its name is cimaquilitl.

Now this next reference comes via the Badianus manuscript (1)

- the Badianus manuscript or the Codex Cruz-Badiano (also the Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis) is the first book on herbal medicine coming from the Americas. It was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano, from a Nahuatl original composed in the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in 1552 by Martín de la Cruz. No copies of the Nahuatl original are known to exist.

Nahuatl name : Cimatl (primary name) (Emmart 1940; Clayton et al. 2009).

Aztec medicinal uses : Remedy for pus already infested with worms. When you see that the suppuration is already wormy, grind together the leaves of quetzalmizquitl, cimatl, and tlalcacapol, and of briar bushes, the root, too, of tlaquilin, and the bark of xiloxochitl, and this in the very best native wine. And the juice is to be applied to the wormy part morning and evening. It is of some value also to apply a medicament of briars, oak bark, and the foliage of quetzalylin, tlalpahtli, quauhpahtli, and tlatlanquaye and the root of tlalhaueuetl, ground in water with the yolk of an egg. This treatment every day, twice morning and evening, until the purulent mass is dried up

This medicinal application uses the leaves and not the root of cimatl.

As it appears in my copy of the English translation of the Badianus manuscript

Lopez Austin notes the medicinal use of cimatl and elaborates a little on the toxicity of the root.

cÍMATL. Es una raíz. Su fronda se llama cuahueco; pero también se llama cimaquílitl. [Sus semillas] son semejantes al ayecotli; se dice: dizque son la semejanza del ayecotli. Es arrojador [de guías]; es rastrero. Tiene flores, tiene vainas, tiene frijoles. Su raíz, verde, cuando no se coció bien, hace vomitar a la gente, causa diarrea a la gente, es mortal. Así se alivia el que ha tomado címatl: se fríe éste, el axin; blando va por el ano. Y para comer esta raíz, durante dos días se asa, para que se cueza bien. Y previamente se calienta, hierve el agua con salitre: en el agua hirviendo lo cuecen también. Yo tomo címatl. Le doy címatl.

cÍMATL. It is a root. Its frond is called cuahueco; but it is also called tumbaquílitl. [Its seeds] are similar to ayecotli; It is said: they are said to be the resemblance of the ayecotli. He is a thrower [of guides]; It’s creepy (1). It has flowers, it has pods, it has beans. Its green root, when not cooked well, makes people vomit, causes diarrhea in people, it is deadly (2). This is how someone who has taken cimatl is relieved: this one, the axin, is fried; soft goes through the anus. And to eat this root, it is roasted for two days, so that it is cooked well. And previously it is heated, it boils the water with saltpeter: in the boiling water they also cook it. I take cimatl. I give him címatl.

- describes a prostrate, creeping, vine like plant

- this is not always the case when using this root though. This leads me to….cimahuia. : Principal English Translation: to put cimatl root in with the sap from the maguey (agave) to give it a good appearance (see Molina) – Alonso de Molina: cimauia. nitla. (pret. onitlacimaui.) echar rayz de cimatl enla miel de maguei para darle buen parecer.

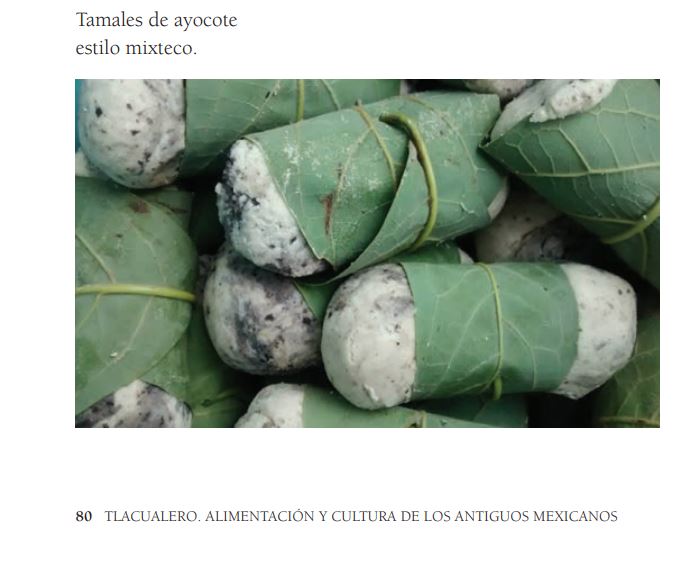

Casas (etal 2016) identifies “cimat” as Phaseolus coccineus L. Leguminosae and notes of its use…“The thickened roots of the frijol ayocote or botil, Phaseolus coccineus are known as cimat (1) . This species of bean is cultivated in the temperate highlands as a monoculture in the plateau region of Puebla and Tlaxcala, Durango, Zacatecas, and Chihuahua, or in association with maize, which is the common form of cultivation in southern Mexico. The growth habit of P. coccineus is highly variable, while always being determinate, varying from sub-shrubs to vines with over 6 m long guides, the latter forms being used for obtaining the roots for consumption. The use of cimat as food has been documented in several ethnic groups from Chiapas, Puebla, Veracruz, and Hidalgo; however, always being well cooked by boiling for up to 12 h, or otherwise it may cause gastric problems such as vomiting and diarrhea”. The same text notes that “There are other roots that are also eaten that are called Cimatl . They are eaten cooked and if eaten raw are harmful. They are naturally white, when cooked becoming yellow.”

- it is not unusual to drop the final “L” in a word when pronouncing it (as part of “tl”) and pronounce the word with a hard “T” rather than the slightly fricative “tl” (2). You’ll find the words Quetzalcoatl pronounced quetzal-co-at and Nahuatl as na-huat (with an almost “what” sounding pronunciation)

- What is difference between sibilant and fricative? – A particular subset of fricatives are the sibilants. When forming a sibilant (an sss or shh sound), one still is forcing air through a narrow channel, but in addition, the tongue is curled lengthwise to direct the air over the edge of the teeth.

Becerra & Salazar (2013) also mention cimatl as being a root, “The food and sustenance of these Teuchichimecas (1) were prickly pear leaves and the same prickly pears, and the root they call címatl, and others that they took out from under earth…”

- Also Teochichimeca(h) – the “divine” chichimeca, the Mexica ancestors – described as completely wild and uncultivated peoples who practised no agriculture at all, lived on hunting and had no fixed places of residence. (Levin-Rojo 2001)

Basurto (etal 2017) identifies cimat with Phaseolus coccineus L. ssp and gives the following data…

Nombre comun (Common name) – flor de cimat, xochiquilit, tacuahuaquet(nah), tangastapu (tot)

Preparacion – hervido con sal, hervido con frijoles, frita (boiled with salt, boiled with beans, fried)

Parte usada – plántulas, hojas, tiernas y flor (seedlings, leaves, tender and flower)

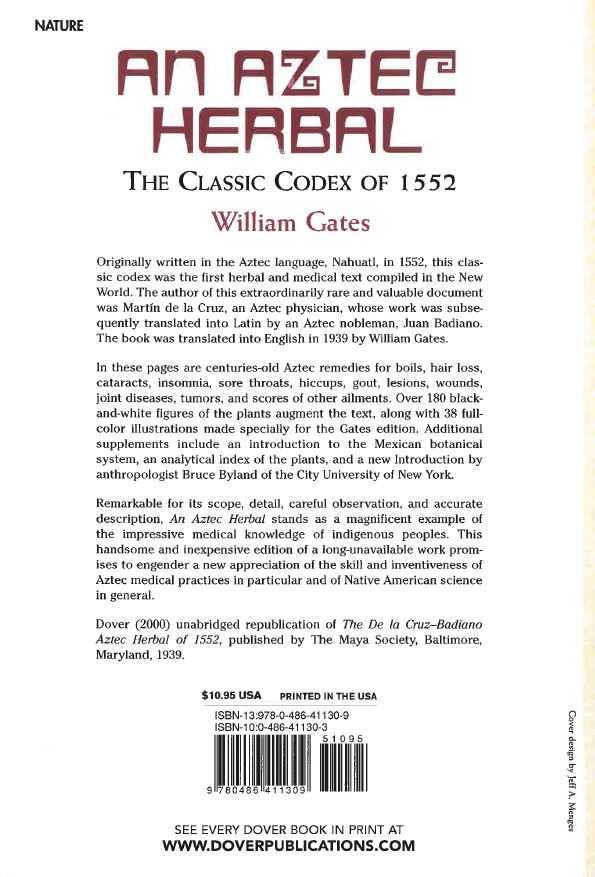

Barros and Buenrostro (2016) note of the ayocote (Phaseolus coccineus) that “Not only the beans are eaten” but that; “also the flowers and leaves (are used) as quelites”. This paper also mentions the use and potential toxicity of the root and that the leaves are used in tamales (and that in Oaxaca the flower is used in a traditional guisado)

There is one line in Lopez Austins entry that draws my curiosity…

“Así se alivia el que ha tomado címatl: se fríe éste, el axin; blando va por el ano.”

Google Translate gives me “This is how someone who has taken cimatl is relieved: this one, the axin, is fried; soft goes through the anus.”, which if I am to understand correctly means that in cases of cimatl poisoning the antidote/treatment is an enema or suppository of axin. Axin?

axin.

Principal English Translation: an insect (Llaveia axin, in the family Margarodidae, order Hemiptera) a genus endemic to Mexico and Guatemala) (personal communication, Alejandro de Ávila Blomberg, 10 May 2022); the insect secrets a substance/ointment used medicinally, and that substance itself is also called axin (see Karttunen)

The “aje” (Llaveia axin axin) is a parasitic hemipteran (1) of various tree species in tropical dry forests of Mexico and Guatemala. Axin is an oily yellowish grease obtained by crushing an insect called Axin, that lives on tropical Spondia trees; the Aztecs also used it as lip balm, and as another remedy for diarrhoea. (Suazo-Ortuño etal 2023)

- Hemiptera means “half wing” and refers to the fact that part of the first pair of wings is toughened and hard, while the rest of the first pair and the second pair are membranous. Hemiptera is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from 1 mm to around 15 cm, and share a common arrangement of modified piercing and sucking mouthparts; some suck plant juices and are plant pests, while others can bite painfully.

(Rosas-Perez etal 2017)

A Mayan name for axin/aje is niij. The insect is processed and used to make a type of lacquer. It is similar in many ways to the domestication and farming of cochineal insects (1) and researchers currently searching for historical use of this insect have noted that “if they have cochineal insects they should also have lacquer insects too”.

Emmacamila Artesanias on Facebook shows some of the steps in processing this insect into a lacquer.

When you harvest the insects, you clean off the white surface layer, and you then see that the insects are a nice light orange colour. They do not bite or sting, nor are they otherwise aggressive. (Hellmuth 2011). You obtain the purified body fat of the insects by crushing the adult Niij females in boiling water, grinding this with a pestle to produce a fat laden liquid , then you filter out the exoskeletons and churn the aqueous extract until the fat coalesces into a semisolid mass; the fat makes up approximately 30% of the total body weight of adults (averaging about 600 mg). The texture and melting point of Niij “wax” are not unlike cocoa butter. (Cano etal 2013). This can then be processed into a lacquer (or a suppository it appears).

Cimatl has been variously identified as…..

- Canavalia villosa Benth

- Cochliasanthus caracalla (L.)

- Phaseolus caracalla L.

- Desmodium amplifolium (Kunth) DC.

- D. orbiculare Schltdl.

- D. parviflorum

- D. scoparium Wall. [unresolved name]

- Macroptilium atropurpureum (DC.) Urb. (Phaseolus atropurpureus DC.)

- Phaseolus coccineus L. (P. multiflorus Willd.)

Lets check some of these plants out

Now, the three plants above fit the profile of a low growing plant likely to be found growing at the feet of the maguey but none are red foliaged.

The two below are on the list but both are fairly large vine growing plants and, again, don’t fit the description (although I am leaning towards a Phaseolus as being the main contender for this plant)

The first three do show some promise as a tamal quelite. They strongly remind me chipilin (chepil) whose leaves are used in tamales. See my Post Quelite : Chipilin : Crotalaria longirostrata for more info on this particular leaf.

This certainly fits the part of the description regarding using the herb in a tamal.

Lets have a look at some red leaved quelites

Quintonil (1) rojo – Many amaranth species quilitl are red leaved (particularly when very young)

- quintonil (and bledo/s) is a common name for the amaranth species quelites. Chichiquilit is also sometimes used to name this plant. Typically Chichiquelite will lead you to Hierba mora (Solanum nigrum/tuberosum) which has a black fruit usually called a huckleberry. Here though I believe the chichi comes from the Nahuatl word for “red” = chichilt(ic)

hojas de sangre

Another red leaved quelite that might fit the bill is a form of Chenopodium species quelite called Cenizo. (Lambs quarters and fat hen are European common names for this herb – pigweed is an American common name)

Called “ash” due to the powdery white covering on the underside of the leaves.

Varieties of Cimatl

(Francisco Hernández )….when describing mexican plants mentions the ayocote or Indian bean, and some of its botanical relatives, such as the

- cimatl (Phaseolus coccineus)

already noted above

- ayecocimatl

ayeco (tli) ayecote – frijol gordo y cimatl (Phaseolus multiflorus)

- cicimatic

Nahuatl etymology: “Cicimatic: from cicima (tl), affective diminutive form of cimati, and tic, suffix already explained. (Plantita) similar to cimatl.”

variously identified as…

Canavalia villosa – Was used by the Aztecs for eye problems, and especially for fleshy growths over the eyes.

Ramirezella strobilophora – cicimatic or a plant similar to cimatl (Ochoterena 2000)

A plant very similar to cimate (Urbina 1906)

A plant similar to the cimatl (Hernández)

- cicimate

Senecio vulneraria – Cicimate – a name derived from Cimatl (Ochoterena-Booth 2000)

- ticimatl

Later, with Hispanic culture already established in America, the Spanish doctor Francisco Hernández, very learned doctor of Philip II, sent to New Spain to write the “Natural History of the Indies”, when describing Mexican plants, mentioned the ayocote. or Indian bean, and some of its botanical relatives, such as the cimatl, cicimatic, ticimatl and tepecimatl. (García Rivas 1991)

- tepecimatl (cimatl sivestre)

cimatl montana/cimatl de monte – “mountain” cimatl (tepetl = hill/mountain/volcano)

Raíces comestibles entre los antiguos mexicanos also mentions

- tecimatl

Cimate de piedra ó en forma de huevo. – Stone cimate or egg-shaped (Urbina 1906)

- tlalcimatl (Desmodium orbiculare)

Cimate humilde ó de tierra. – Humble or earthen cimate. (Urbina 1906)

- Quauhtocimatl

- Cimate que se siembra por acodos ó estaca. – Cimate that is planted by layers or stakes.

- Cimatl de Totopec (Desmodium scoparium)

- Cimapatli de Acatlan (Glycyrrhiza lepidota)

- Quauhtoccimatl – Cimate de estaca.

- Quauhcimatl (Gonolobus erianthus)

A Botanical Explanation?

Perhaps all of this has been due to a misunderstanding of a botanical explanation of the plants.

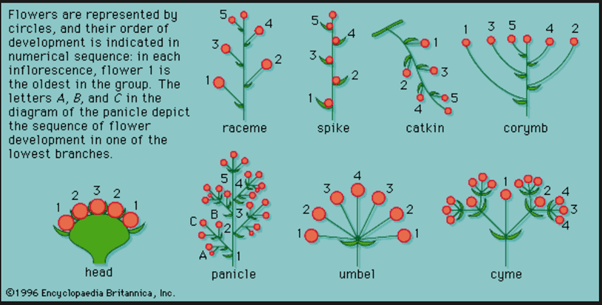

A cyme (cima in Spanish) is a botanical term for a specific type of flower structure. Technically speaking “A cyme is a flat-topped inflorescence (1) in which the central flowers open first, followed by the peripheral flowers” or (more digestibly) “A Cyme is a group of flowers in which the end of each growing point produces a flower, so new growth comes from side shoots and the oldest flowers are at the top”.

So….perhaps…..in the cataloguing of the plant, and the description of the flower (flor) being a cyme (cima) in structure and then the transcribing of this by another researcher, the “flor de cimal” or the herb with the “cyme shaped inflorescence” was born from the confusion?

Research continues.

References

- Andrews, James Richard (2003). Introduction to Classical Nahuatl. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-8061-3452-9

- Barros, Cristina y Buenrostro, Marco (2016) Tlacualero. Alimentación y cultura de los antiguos mexicanos, 2016 : Primera edición : ISBN 978-607-7797-23-4 Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán

- Basurto, Francisco & Martínez-Alfaro, Miguel & Villalobos-Contreras, Genoveva. (2017). Los Quelites de la Sierra Norte de Puebla, México: Inventario y formas de preparación. Botanical Sciences. 49. 10.17129/botsci.1550.

- Becerra, Rosalba & Salazar, Martha Alicia. (2013) Identidad a través de la cultura alimentaria : memoria simposio : Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad Liga : ISBN 978-607-7607-77-9

- Brignone, N.F., Pozner, R.E. and Denham, S.S. (2019), Origin and evolution of Atriplex (Amaranthaceae s.l.) in the Americas: Unexpected insights from South American species. TAXON, 68: 1021-1036. https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.12133

- Bye, Robert & Linares, Edelmira. (2013). Codex de la Cruz-Badiano: Prehispanic medicine. Part one. 8-14.

- Bye, Robert & Linares, Edelmira. (2015). Perspectives on Ethnopharmacology in Mexico. 393-404. 10.1002/9781118930717.ch33.

- Bye, Robert & Linares, Edelmira. (2016). Ethnobotany and Ethnohistorical Sources of Mesoamerica. 10.1007/978-1-4614-6669-7_3.

- Bye, Robert & Linares, Edelmira. (2023). Ethnobotany in the Sierra Tarahumara, Mexico: Mountains As Barriers, Conduits, and Generators of Plant-People Interactions and Relationships. 10.1007/978-3-030-99357-3_5

- Cano, Enio. (2013). Adaptive radiation in the tropics: entomology at the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala..

- Carrillo-Galván, Guadalupe & Bye, Robert. (2023). Agastache spp. Lamiaceae. Important Species of Hyssop in Mexico. 10.1007/978-3-030-99357-3_24.

- Casas, Alejandro; Lira, Rafael & Blancas, José (2016). Ethnobotany of Mexico: Interactions of People and Plants in Mesoamerica. 10.1007/978-1-4614-6669-7.

- Clayton, M., L. Guerrini, and A. de Ávila. 2009. Flora: The Aztec herbal. London: Royal Collection Enterprises.

- Díaz JL. Ethnopharmacology and taxonomy of Mexican psychodysleptic plants. J Psychedelic Drugs. 1979 Jan-Jun;11(1-2):71-101. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1979.10472094. PMID: 392121.

- Emmart, E. W. 1940. The Badianus Manuscript (Codex Barberini, Latin 241). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press.

- García Rivas, Heriberto (1991) Cocina Prehispánica mexicana “la comida de los antiguos mexicanos” Panorama Editorial, S.A. de C.V. ISBN 968-38-0258-3

- Hellmuth, Dr. Nicholas M. Sacred animals and Exotic tropical Plants : The Niij “Domesticated insects were part of the Mayan civilization” : https://www.maya-archaeology.org/FLAAR_Reports_on_Mayan_archaeology_Iconography_publications_books_articles/35_The-Niij-domesticated-insects-part-of-Mayan-civilization-cochinilla-cochineal-red-orange-color-Guatemala-Revue-Magazine-December-2011-FLAAR-Reports.pdf

- Hernández, Francisco (Médico e Historiador de Su Majestad Felipe II, Rey de España y de las Indias) : Historia de las plantas de la Nueva. Espana : TOMO I : Libros 1 y 2

- Karttunen, Frances (1992)An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992)

- Lee, Jee & Hwang, Johye & Mustapha, Azlin. (2014). Popular Ethnic Foods in the United States: A Historical and Safety Perspective. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 13. 10.1111/1541-4337.12044.

- Levin-Rojo, Danna Alexandra (2001) A Way Back to Aztlan: Sixteenth Century Hispanic-Nahuatl Transculturation and the Construction of the New Mexico : Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. UMI Number: U615219

- Linares, Edelmira & Bye, Robert. (2014). Plants that Mexico has contributed to the world. 22. 52-59.

- Linares, Edelmira & Bye, Robert. (2016). Traditional Markets in Mesoamerica: A Mosaic of History and Traditions. 10.1007/978-1-4614-6669-7_7.

- Linares, Edelmira. (2017). La buena y la mala cara de las malezas: nuevo recuento de las plantas arvenses para el estado de Querétaro. Reseña del libro: Atlas de malezas arvenses del estado de Querétaro. Suárez-Ramos G., Serrano-Cárdenas V., Balderas-Aguilar P. y Pelz-Marín R. (eds. Botanical Sciences. 119. 10.17129/botsci.1726.

- Linares, Edelmira & Bye, Robert & Nava, Noemí & Valdez, Antonio. (2019). Quelites: sabores y saberes del surste del Estado de México. 10.22201/ib.9786073016667e.2019.

- Lockhart, James (2001) Nahuatl as Written: Lessons in Older Written Nahuatl, with Copious Examples and Texts (Stanford: Stanford University Press and UCLA Latin American Studies, 2001),

- LÓPEZ AUSTIN, Alfredo (1993) Textos de Medicina Nahuatl : Instituto de Investigaciones Historicas : Serie de Cultura Náhuatl – Monografías: 19 : Tercera Edicion : Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México : ISBN 968-36-2988-1

- Lopez Austin, Alfredo. (2022) DESCRIPCIÓN DE MEDICINAS EN TEXTOS DISPERSOS DEL UBRO XI DE LOS CÓDICES MATRITENSE Y FLORENTINO : https://ru.historicas.unam.mx/bitstream/handle/20.500.12525/2304/78488-Texto%20del%20trabajo-231483-1-10-20221104.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Lugo-Morin, D.R. Looking into the past to build the future: food, memory, and identity in the indigenous societies of Puebla, Mexico. J. Ethn. Food 9, 7 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-022-00123-w

- Małgorzata Martynuska : Cultural Hybridity in the USA exemplified by Tex-Mex cuisine : International Review of Social Research 2017; 7(2): 90–98 : DOI 10.1515/irsr-2017-0011

- Ochoterena-Booth, Helga (2000) Identity and current ethnobotanical knowledge of Francisco Hernandez’s “Cicimatic” Journal of ethnobiology Volume 20 (1) Summer 2000

- Pacheco-Pantoja, Sara & Mulík, Stanislav & Hernández-Carrión, María & Ozuna, César. (2022). Knowledge and consumption of endemic edible flowers in Mexico. 10.13140/RG.2.2.17752.16647.

- Padmavathi, Bolisetty & Babu, Ankem & Naveen, R. & Kiranmai, Kaja & Prameel, Valluru. (2021). A PHYTOPHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEW ON PHASEOLUS VULGARIS. International Journal of Research in Ayurveda and Pharmacy. 12. 118-123. 10.7897/2277-4343.120386.

- Rosas-Perez, T., Vera-Ponce de Len, A., Rosenblueth, M., Ramirez-Puebla, S. T., Rincon-Rosales, R., Martinez-Romero, J., … Martinez-Romero, E. (2017). The Symbiome of Llaveia Cochineals (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Monophlebidae) Includes a Gammaproteobacterial Cosymbiont Sodalis TME1 and the Known Candidatus Walczuchella monophlebidarum. InTech. doi: 10.5772/66442

- Suazo-Ortuño, Ireri; del Val-De Gortari, Ek; Benítez-Malvido, Julieta (2013) Rediscovering an extraordinary vanishing bug: Llaveia axin axin : Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 84, núm. 1, marzo, 2013, pp. 338-346 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México

- A. O. Tucker, J. Janick, Flora of the Codex Cruz-Badianus, © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46959-7_2

- Turpin, David C. The Origin of Common Spanish Names for Fifteen Well-known Plants of Mexico : Plants of Mexico Vol. 35, No.2 (June 1987)

- URBINA, Dr Manuel; (Jefe del Departamento de Historia Natural en el Museo) Raíces comestibles entre los antiguos mexicanos : 1906

Websites

- ahuehuetl. – De Luisalvaz – Nonehhuiyan notlachihual, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39290623

- angiosperm inflorescences : Encyclopædia Britannica : https://www.britannica.com/science/cyme#/media/1/148383/385 : Access Date23 February 2024

- axin. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/axin

- cima – https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cima

- cima – https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/cim%C3%A1

- Cima/atl – https://aztecglyphs.wired-humanities.org/content/cima-mh520rCamotl – https://aztecglyphs.wired-humanities.org/content/camotl-mdz44r

- cimahuia. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/cimahuia

- huehuetl. _ https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/huehuetl

- Karen Hursh Graber : A culinary guide to Mexican herbs: Las hierbas de cocina : Published or Updated on: April 1, 1999 (Accessed 05.02.2024) : https://www.mexconnect.com/articles/2187-a-culinary-guide-to-mexican-herbs-las-hierbas-de-cocina/

- Niij – https://www.maya-art-books.org/Mayan-domesticated-animals-insects-Mexico-Guatemala/niij-Llaveia-axin-scale-insect-Achi-Mayan-bibliography-handicrafts-Rabinal-lacquer.html

- Phaseolus coccineus L – https://www.malinal.net/lexik/nahuatlC.html#CIMAQUILITL

- Sierra Madre Oriental – By NASA – World Wind, inscription by Raymond – Raimond Spekking, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=178817

- xiuh iximatqui. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/xiuh-iximatqui

- xiuh izhuatl. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/xiuh-izhuatl

- xiuhcamotli. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/xiuhcamotli

- xiuhmateca. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/xiuhmateca

- xiuhtopehua. – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/xiuhtopehua