6 July 1840 – 26 August 1912 : José María Tranquilino Francisco de Jesús Velasco Gómez Obregón, generally known as José María Velasco, was born in Temascalcingo (just outside Mexico City). He was a 19th-century Mexican polymath (1), most famous as a painter who made Mexican geography a symbol of national identity through his paintings (2), particularly those depicting the Valley of Mexico.

- Polymath – a person of encyclopedic learning. A polymath is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. From Greek polumathēs ‘having learned much’, from polu- ‘much’ + the stem of manthanein ‘learn’.

- Mexican artists tended to do this though, use their country as inspiration I mean, and why wouldn’t you? Eh? Check out my Post Mexican Artist : Amendolla. It’s got nothing to do with Xochipilli but it is a Mexican artist whose work I have recently encountered and who also used México as his muse (particularly the area around Tepoztlan).

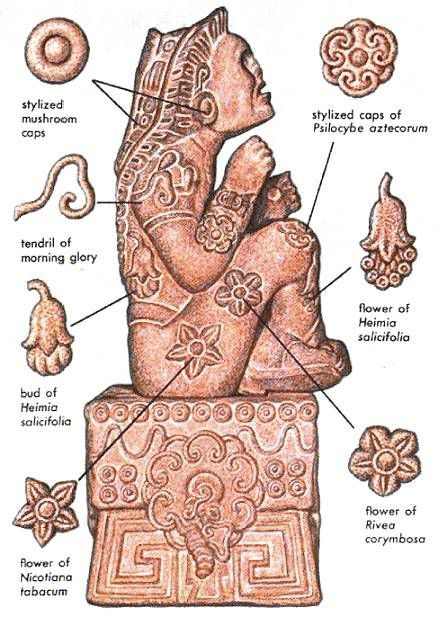

Xochipilli has been a figure of study in my life for more than 30 years. I too was initially drawn to this avatar (1) due to Wassons misinterpretations of hallucinogenic plants. I did have many questions even at the beginning and was never convinced. Being a herbalist myself (and plant person in general) his interpretations did not sit quite right and appeared to be of the sort of “ritual use” explanation proffered by archaeologists when they’ve got absolutely no idea what the (insert macguffin here) is or is used for. Mundane items are often over explained. Mesoamericans were also expert botanists and agriculturalists whose understanding of the universe and explanations of its mechanics operated from a very different worldview to that of our own. Wassons shoehorning of all of Xochipillis floral emblems into being those of hallucinogenic plants always felt forced and incomplete.

- Just in case you’re wondering. “Avatar” comes from the Sanskrit word avatāra meaning “descent”. Within Hinduism, it means a manifestation of a deity in bodily form on earth, such as a divine teacher. For those of us who don’t practice Hinduism, it technically means “an incarnation, embodiment, or manifestation of a person or idea”

There has also been a relatively recent push to homosexualise Xochipilli. Many Mesoamerican “deities” do exhibit a type of gender fluidity and it is a mistake to ascribe homosexuality to these as the Aztecs had a very particular system of belief regarding balance in the universe (and very rigid and harsh rules regarding homosexuality). Feminine (or masculine) actions and even forms of being can be attributed to the various deities (as they can and do for us normal humans) in the process of demonstrating balance within the universe and the need/duty/responsibility of these various deities to ensure that this balance is kept. We also need to practice diligence when researching this subject as the primary source material for “perversion” amongst the indians was tabulated by the Spanish. Aside from the usual claims that these people were ignorant, uneducated, Godless heathens; accusations of orgies, sodomy, paedophilia and even child (as young as 6) prostitution were levelled at various people and groups. This is a usual tactic of the Catholic Church when they wish to take what they covet.

Queerness, and the acceptance of it, is currently undergoing the same kind of evolution/revolution that women’s rights/feminism had in the 60’s and 70’s and one aspect of this has eventuated with subsuming Xochipilli into not only being a queer icon but a specific deity of male homosexuality. This is not the correct way to approach Xochipilli if you seek true understanding of this particular force of nature. See Aztec Gods or States of Consciousness? for more information.

For further information on my explorations into Xochipilli please see the following….

- Xochipilli. The Prince of Flowers

- Aztec Gods or States of Consciousness?

- Xochipilli : New Floral Identifications

- Xochipilli and Homosexuality : Part 1

- Xochipilli and Homosexuality : Part 2

- Xochipilli : Beyond Gender

- Xochipilli : Hymn to Xochipilli

- Xochipilli : Xochipilli and the Butterfly – Not yet published

- Xochipilli : Is it a Dahlia?

- Xochipilli and the Macuiltonaleque – Not yet published

- Xochipilli : Intoxicating Scent.

- Xochipilli : A Force of Nature

- Xochipilli : Cacao Cults and Sunstones. – Not yet published

- El Avatar de Xochipilli

- Xochipilli and the Zapote – Not yet published

The information in this Post was largely gleaned from an article by Enrique Vela published in Arqueología Mexicana Especial Núm. 96 Obras Maestras Visión del México Antiguo

Text from Enrique will be in BOLD (everything else will be notes added by me)

Chapter 18. XOCHIPILLI.

TLALMANALCO, STATE OF MEXICO

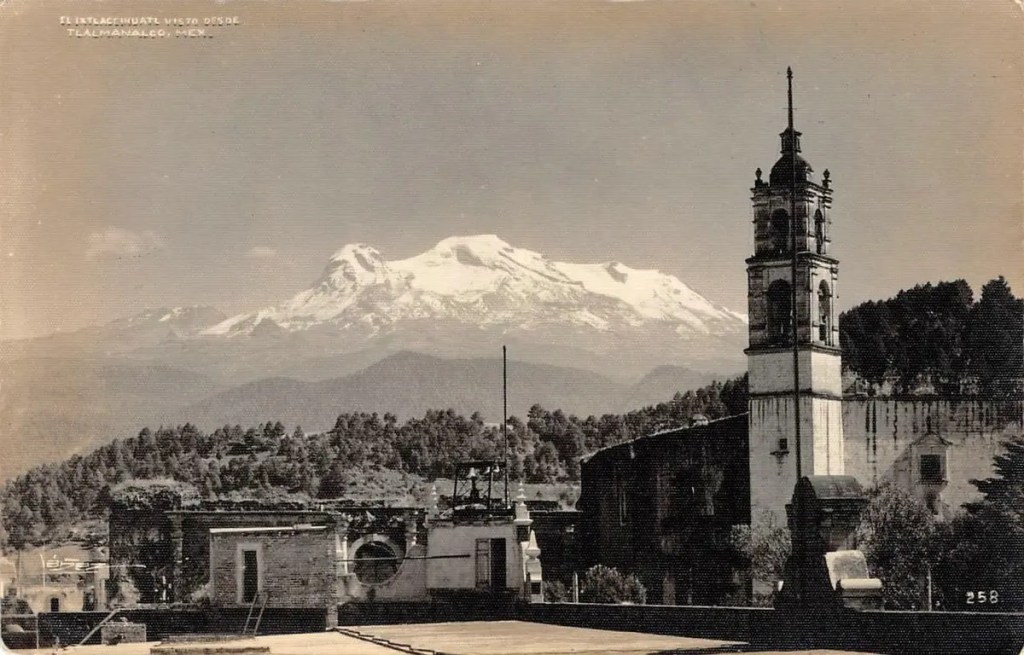

Our story starts in Tlalmanalco where the statue of our protagonist was found buried (some stories say face down) on the slopes of the volcano Popocatepetl.

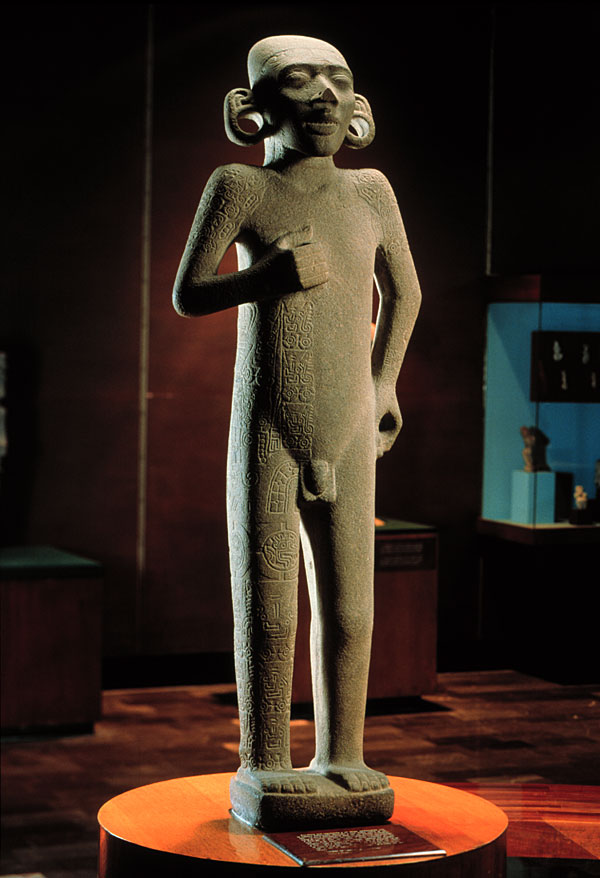

Others say the statue was found on the slopes of Popos lover Iztaccihuatl (Aguilar-Moreno). “The picturesque town of Tlalmanalco, once part of the province of Chalco, is situated at the foot of the volcano Iztaccihuatl in the Valley of Mexico and was an important preColumbian religious center and a region famous for its artists. Here the sculpture of Xochipilli, the Aztec god of flowers, music, dance and feasting, was found. Whether the statue depicts a priestwearing the mask of Xochipilli or whether the statue depicts the god himself is unclear.” 91)

- others have also noted the statue “was unearthed on the western slopes of the volcanoes Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl near Tlalmanalco, south-eastern Mexico. The statue is now housed in the Museum of Anthropology and History of Mexico City”. Now, how the statue can be found on the western slopes of two different mountains is beyond me.

(click image to expand)

Enrique Vela

- Escuela Nacional de Antropología y Historia. – The National School of Anthropology and History (ENAH) belongs to the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). The ENAH is the institution that has contributed the most to the teaching of anthropology in Mexico and Latin America. INAH was founded in 1938 within the Department of Anthropology of the School of Biological Sciences of the National Polytechnic Institute. The National Institute of Anthropology and History was created in 1939, and in 1946, the School received its current name.

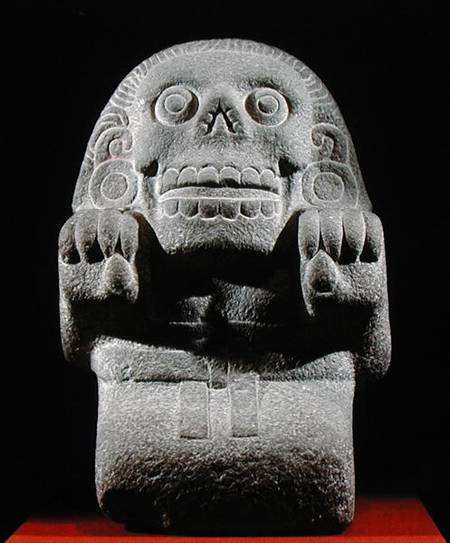

The carving is one of the great examples of pre-Hispanic sculpture; Coming from the Chalco region, it is notable for its technical quality and its symbolism. It is a representation of Xochipilli, “the lord of the flowers”, a god related to music, song, dance, games and sexual pleasure.

Xochipilli was also associated with fertility and the renewal of life and it is in this aspect that he is represented in this statue.

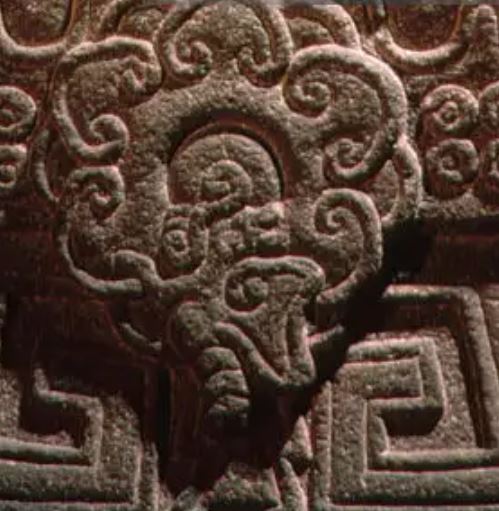

The motifs that adorn the seat on which the god rests – such as the large flowers that emerge from the earth, butterflies and solar symbols – indicate that he transits from the underworld to the terrestrial realm (much in the same way a sprouting seed breaks through the surface of the soil into the life-giving sunlight).

The statue conveys the same meaning:

Xochipilli is a being that comes from the underworld to the terrestrial plane. Among the garments that the god wears are ornaments made with the skin of the cipactli , an animal with which the gods formed the earth; in the headdress there are elements that relate him to the Sun.

For an excellent rendering of the creation myths of Cipactli (and the creations of the various “Suns” – or Ages/Eras) check out https://owlcation.com/humanities/Aztec-Creation-Story-for-Kids-Tezcatlipoca-and-Quetzalcoatl

Seler (etal 1990) points to the four circles arrayed in a square pattern on Xochipillis headdress as being an emblem of the tonallo (see point 7 regarding Caption explanations below). These symbols are also on the statues base.

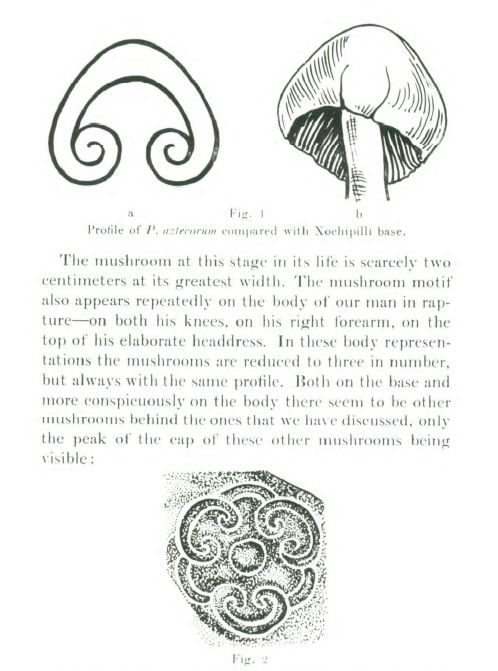

A very popular interpretation for a long time supposed that the representations on the body of the god were of hallucinogenic plants and that he was in a trance; we now know that they represent flowers of different kinds and with meanings related to fertility and life.

- Debunk – expose the falseness or hollowness of (an idea or belief).

Museo Nacional de Antropología.

FOTOS: ARCHIVO DIGITAL DE LAS COLECCIONES DEL MNA, INAH-CANON.

Captions – anticlockwise starting from statues right hand (at left of image)

- Las manos al parecer sostenian algun elemento, tal vez un yollotopilli.

- Dalia, Llamada en nahuatl acocoxochitl, es una de las flores caracteristicas de Mexico. En la epocha prehispanica tenia una notable importancia en la vida ritual, y con ella se elaboraban coronas, guirnaldas y ramilletes.

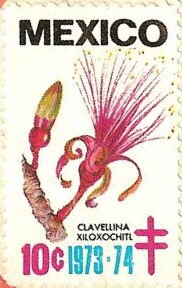

- Xiloxochitl. La flor del jilote, tambien conocida como flor de elote, es una de las flores con mas connotaciones simbolicas en la epocha prehispanica. Se encontraba entre las especies que se preferia ofrendar a los dioses y era considerada un elemento fundamental en la cosmovision.

- Cenefa de flores xiloxochitl.

- Linea ondulada.

- Sandalias.

- Tonalli.

- Dalia. Abarca las mitades superior y inferior, puede verse como un elemento que une asi el inframundo con el cielo.

- Mariposas. Se creia que eran las almas de los guerreros muertos en la batalla, que con su sangre alimentaron al Sol. Eran vistas, ademas, como metaforas de la transformacion vital, Su metamorphosis de gusano a mariposa se consideraba como un paso del inframundo a la tierra y el cielo.

- Portal. Conexion con el inframundo.

- Cenefa formada pequenas flores xiloxochitl, vistas perfil.

- Las ajorcas, formadas por bandas cubiertas con espinas del cipactli, relacionan a Xochipilli con la Tierra.

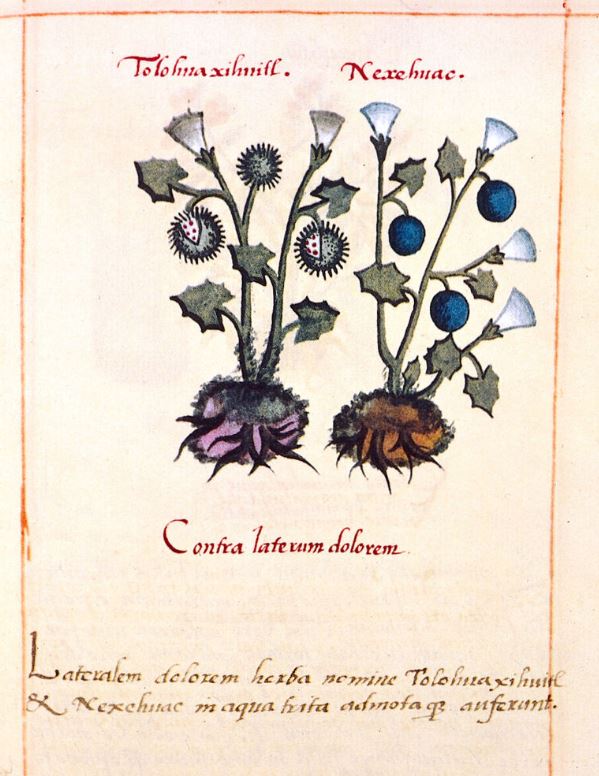

- Toloache. Es una especie particularmente apreciada, ademas de por sus propiedades medicinales, porque su ingesta altera la conciencia y supone una via comunicacion con lo divino.

- Flor de cuatro petalos. La flor de jazmin, en nahuatl aquilotl, es una de las flores de alto valor simbolico por estar asociada a la representacion del universo, con cuatro rumbos y centro. Se le apreciaba asimismo por su belleza y su exquisito olor.

- Pectoral que simboliza al cipactli, ser fantastico semejante a un caiman cubierto de espinas. De el, segun la mitologia nahua, los dioses hicieron la Tierra.

- Orejeras.

- Mascara, tal vez hecha con piel humana.

Translations of the above points

1.The hands apparently held some element, perhaps a yollotopilli.

The yollotopilli has also been described as “a banner topped with a heart with sprouting blood resembling flower petals or feathers” (de Orduña 2008).

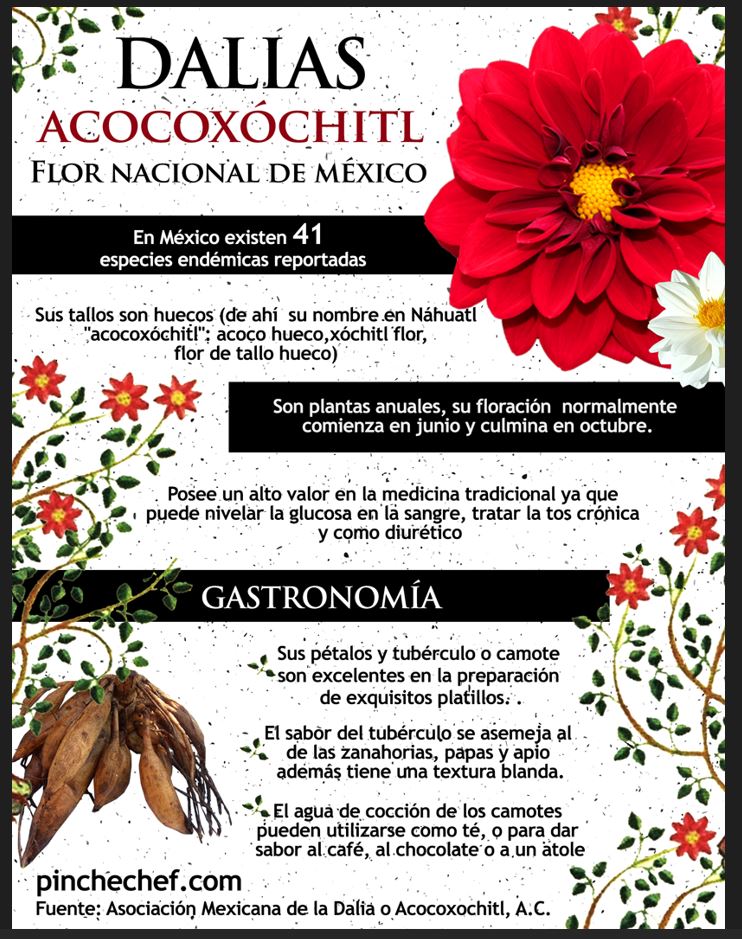

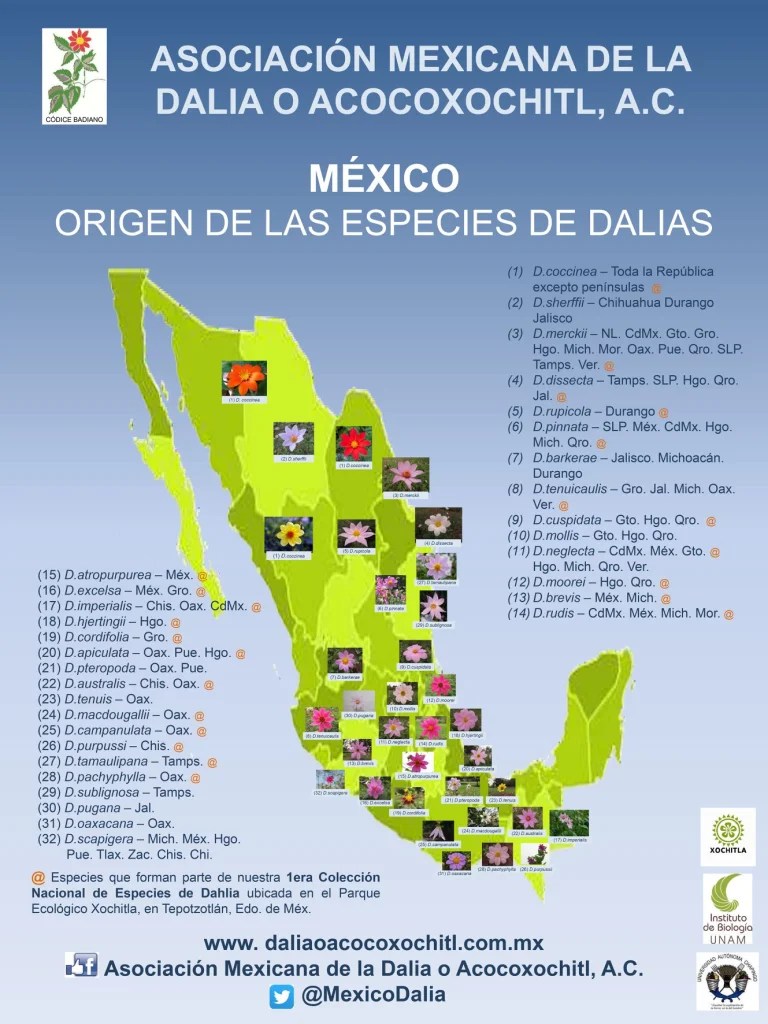

2.Dahlia, called acocoxochitl in Nahuatl, is one of the characteristic flowers of Mexico. Not only is it characteristic of Mexico but in 1963 it was declared the National Flower of Mexico. See my Post Acocoxochitl : The Dahlia for more detail on this plant.

In pre-Hispanic times it had a notable importance in ritual life, and crowns, garlands and bouquets were made with it.

3.Xiloxochitl. The corn flower (la flor de jilote), also known as flor de elote, is one of the flowers with the most symbolic connotations in pre-Hispanic times. It was among the species that was preferred to offer to the gods and was considered a fundamental element in the worldview.

When you search the term xiloxochitl (“flower of the young ear of maize”) you are likely to come across this. The flowers of the Psuedobombax species are so named due to their resemblance to the female corn tassel. Its fruit is edible, its leaves, flowers and wood have been used for medicinal remedies (Cabada-Aguirre etal 2023)

Two large ears of maize rise from her floral headband, with long tassels flowing down her back.

The Aztecs held an agricultural festival in Xilonen’s honour to celebrate the first fruits of the summer season.

During this ritual ceremony, a young girl impersonated the goddess, dancing to bring forth an abundant harvest.

The name Xilonen was Hispanicized in Mexico as elote, meaning “fresh, tender ear of corn.”

(Xilonen- xilote – jilote – elote)

4.Border of xiloxochitl flowers.

5.wavy (undulating) line.

6.Sandals.

7.Tonalli.

The four circles placed in this configuration do not represent mushrooms (rack off Wasson) but are a solar symbol representing the tonalli.

The Nahua people of Mesoamerica believed that the soul comprised three entities: Tonalli, Teyolía, and Ihíyotl, three souls in the body. Tonalli is located in fontanelle area of the skull. Teyolía is located in the heart and Ihíyotl is in the liver. Tonalli’ derives from ‘tona’, a word that means “heat” and is associated with the sun, the sun’s warmth, and individual destinies. The tonalli was located in the head, and the Aztecs believed that creator deities placed the tonalli in an individual’s body before birth.

tona.

Principal English Translation: to be warm, for the sun to shine (see Karttunen and Molina); for it to be hot or sunny (see Lockhart and Molina); or, to prosper; it shines, he shines

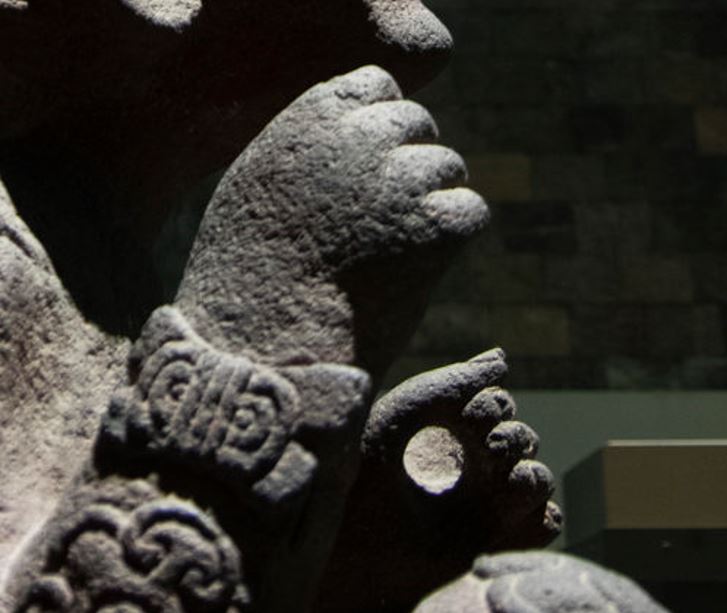

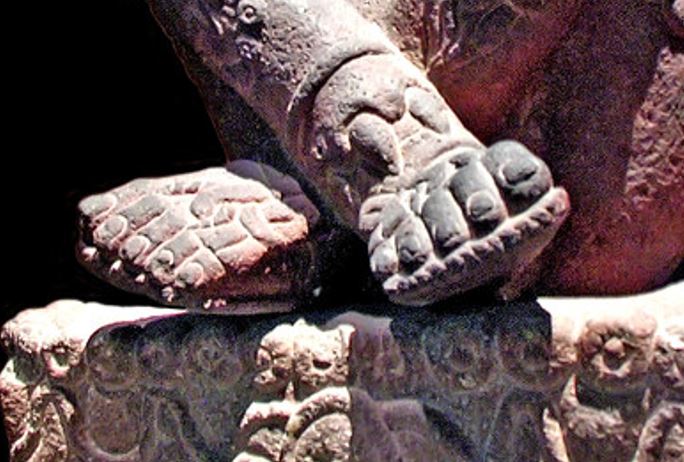

8.Dahlia. Covering the upper and lower halves, it can be seen as an element that thus unites the underworld with the sky. Xochipilli : Is it a Dahlia?. You can see in the image below of the base of Xochipilli’s statue (in which I show a butterfly) the flower that the butterfly feeds from is a dahlia and not an artistic rendering of an imaginary image made from the cross-sections of a psilocybin mushroom as Wasson proposes.

Wasson even questions whether or not it is a butterfly as “In this world of nature mushrooms do not draw butterflies” but, as butterflies play an important mythic role in both Nahua and Mixtec philosophy, it is obvious to him that “on the base of the statue (of Xochipilli) the butterfly is feasting on the flesh of the divine mushrooms, the spirit food of the gods, to whose world the mushrooms transport for a brief spell the people of this sad work-a-day world”. If mushrooms do not draw butterflies then what in Gods name led him to the conclusion that butterflies eat the bloody things?

9.Butterflies. It was believed that they were the souls of the warriors killed in battle, who fed the Sun with their blood. They were also seen as metaphors of vital transformation. Their metamorphosis from a worm to a butterfly was considered as a passage from the underworld to the earth. and the sky.

10.Portal. Connection with the underworld.

11.Border formed by small xiloxochitl flowers, profile views.

12.The anklets, formed by bands covered with cipactli spines, relate Xochipilli to the Earth.

13.Toloache. It is a particularly appreciated species, in addition to its medicinal properties, because its ingestion alters consciousness and is a means of communication with the divine.

14.Four petal flower. The jasmine flower, in Nahuatl aquilotl, is one of the flowers of high symbolic value because it is associated with the representation of the universe, with four directions and a center. He was also appreciated for his beauty and his exquisite smell.

aquilotl.

Principal English Translation:

a plant whose leaves have medicinal value (see attestations)

Attestations from sources in English:

“a voluble plant that grows next to water…a handful [of leaves] drunk with wine gets rid of flatulence; mashed and applied as a plaster, it loosens stiff limbs, and resolves tumors and abscesses.” (Central Mexico, 1571–1615)

Aquilpa – The Place of the Water Plants.” Though aquilitl does not appear in the works of Hernandez, its etymology is clear: atl + quilitl (water + plant). The aquilotl, however, is described as a water plant used commonly in the fabrication of perfume (Oettinger 1982)

15.Pectoral (1) that symbolizes the cipactli, a fantastic being similar to an alligator covered in thorns. From him, according to Nahua mythology, the gods made the Earth.

1 pectoral = relating to the breast or chest

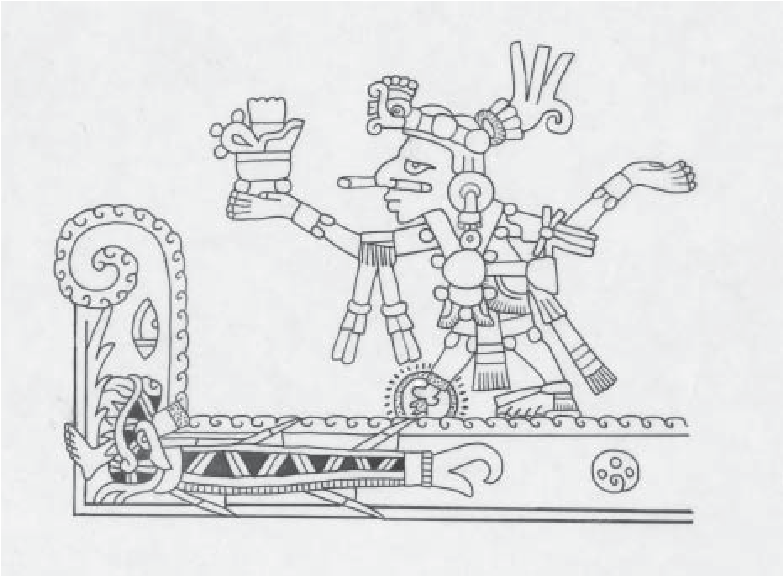

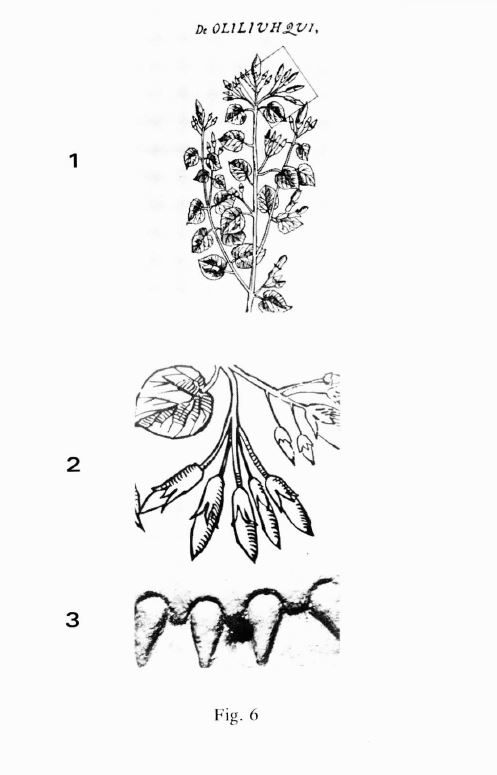

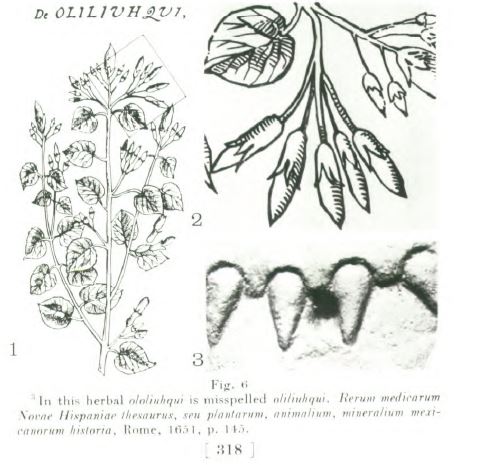

Wasson (1974) identified this fanged pectoral as being the plant Ololiuqui.

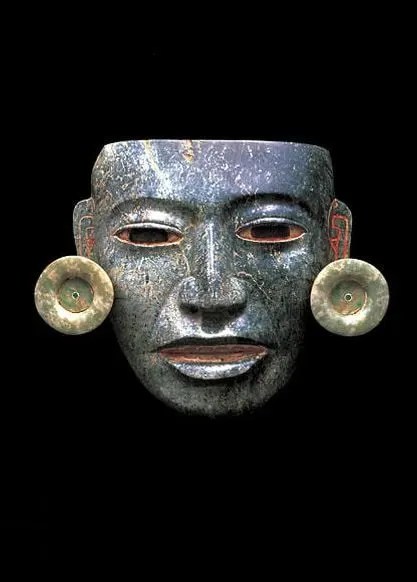

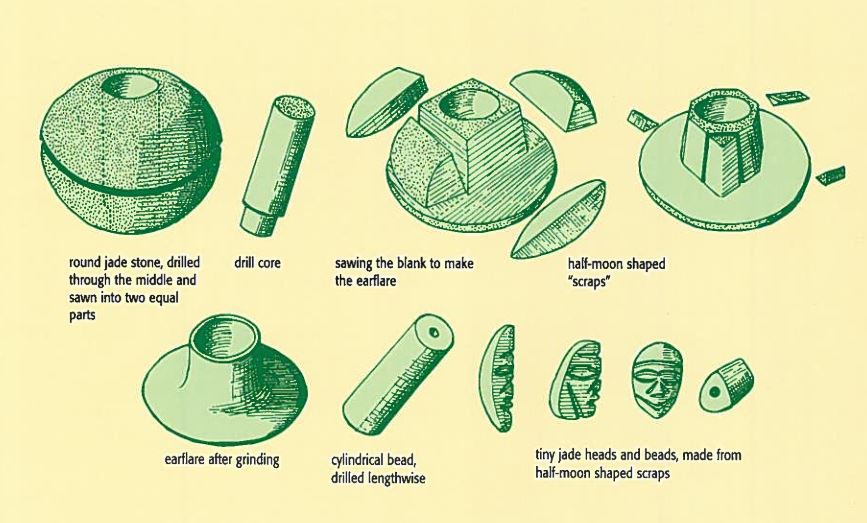

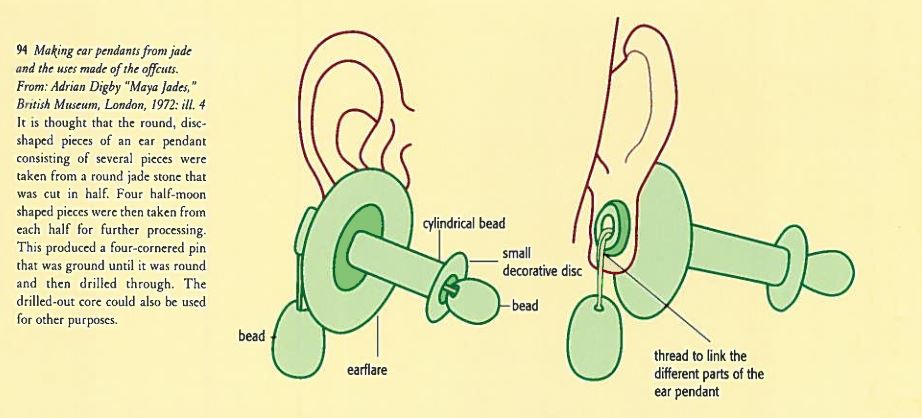

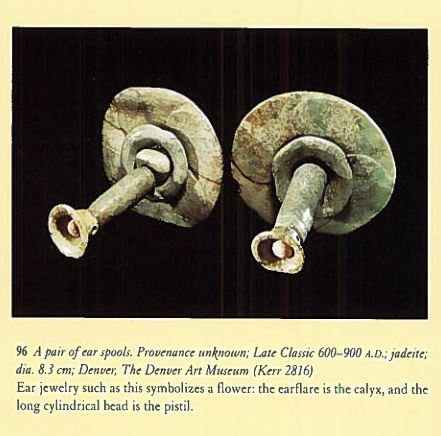

16.Ear muffs. (???) These are not the things you put over your ears to protect them from the cold or loud noises. These are ear piercings and body modifications (in the arena of ear lobe stretching). Wasson tried his level best to connect these ear plugs with the symbolism of the ‘wondrous mushroom”. There was no way in his mind that they were more mundane items, and they could not simply be jewellery or ornamentation. This is just one example of how Xochipilli has been forced into an explanation (rather than the other way round)

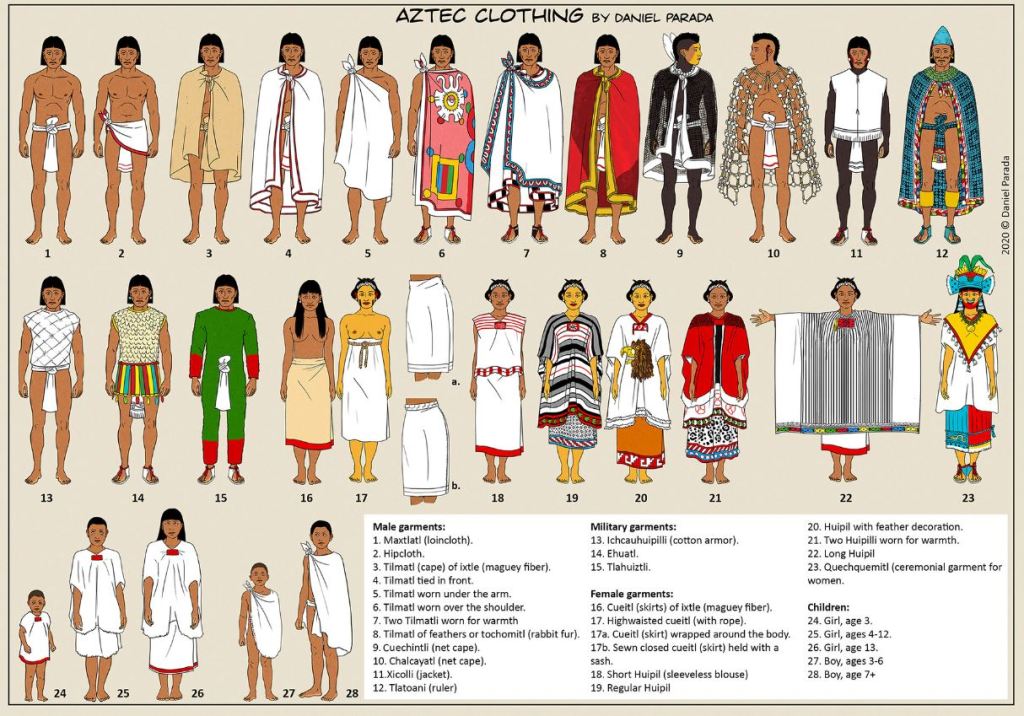

This kind of body modification was commonplace. In this respect Mesoamericans were very much like us. They fussed over social status and all of its various trimmings. Fashion was somewhat regulated (only certain classes could wear certain materials for instance – cotton robes were restricted to the noble classes and the wealthy (if they were discrete about it). These people were as fickle about their appearance as any modern day hipster.

Ear plugs as demonstrated in various artworks

The ear gauges worn by the Maya looked similar to the gauges many ear lobe stretching hipsters wear today. The Maya stretched their earlobes by threading a string through the piercing and attaching either jade or obsidian beads to the end. Over time, the weight of the stone would stretch the piercing, eventually making it possible to attach the ear gauge.

Nasal ornamentation.

Lip piercing.

The most extreme body modification (and I can only see it as type of fashion as I cannot see a practical reason for it) is that of cranial deformation. Aliens? Yeah, nah. Fashion? But why though? Not my area.

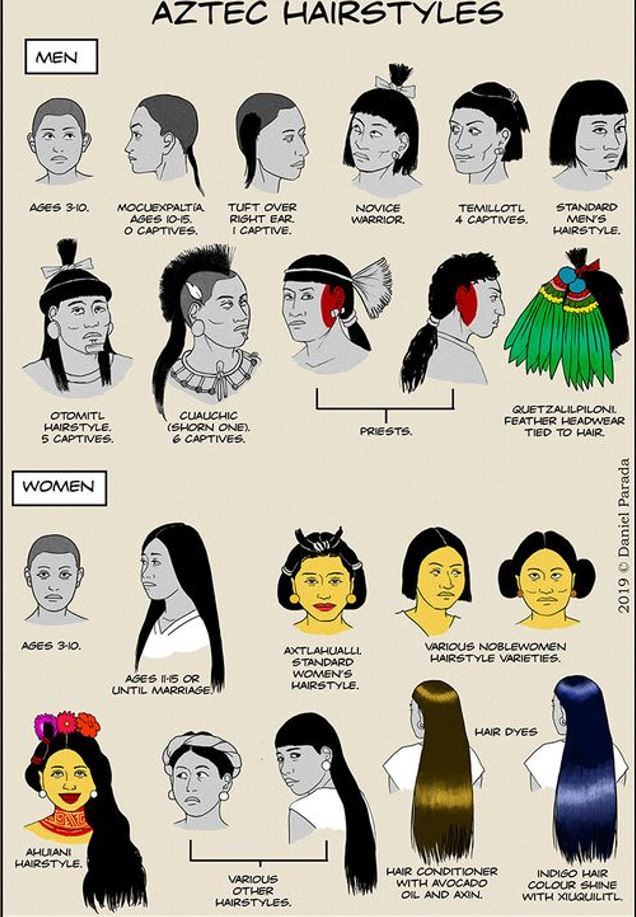

Hair and clothing fashions and styles.

All of these were regulated by your social class/standing. for instance a commoner who demonstrated proficiency in battle and captured many souls for Huitzilopochtli’s altar could easily rise through the ranks of Aztec society and reach a much higher social class (potentially even becoming a tlatoani) than the one he was born into. Upward mobility for women was usually attained through marriage.

.…and even tattooing and scarification

The Maya also had a God specifically of tattooing and body scarification called Acat.

….and I wont even begin to go into the Mesoamerican penchant for masks which is a thesis in and of itself and the depths of which has been delved into by the most celebrated of Mexico’s poets and philosophers.

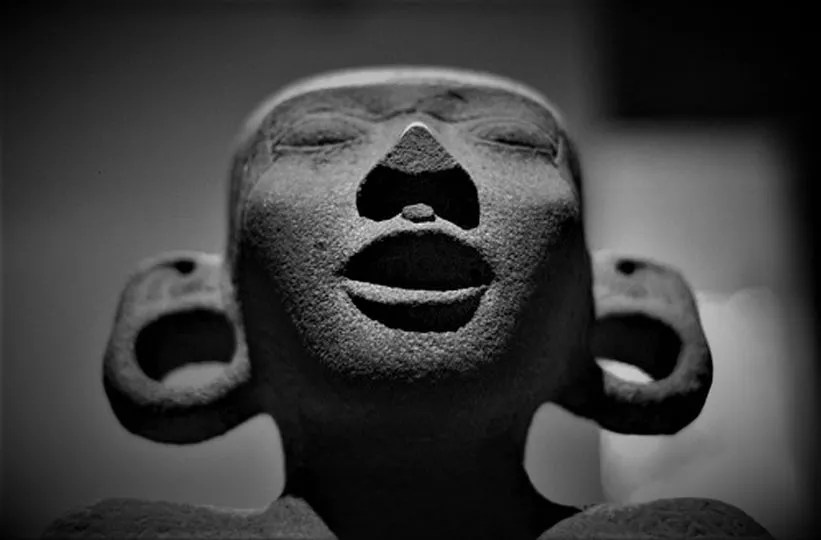

17.Mask, perhaps made from human skin.

Images showing the (possible) mask Xochipilli is wearing. In the poem Xochipilli icuic (Hymn to the God of Flowers) Xochipilli is referred to as the “Lord of the bells” with the “thigh skin facial paint” (Sahagun etal 1997). Knab and Sullivan (1994) offer a slightly different translation and refer to Xochipilli as “The Lord of the bells, the possessor of the thigh skin facial paint”. You can see on the statue above (around the chin area) where there is a definite double layer and may indicate something laying upon the face (such as a mask made from the skin flayed from the thigh of a human)

mexāyacatl:

- mask made with the skin of the thigh of a sacrificial victim.

- mask made with agave leaves.

The term has two different etymologies and designates two different masks. It is either metz-xāyacatl, a mask made with the skin of the thigh of a sacrificial victim, or a mask made with agave leaves, me-xāyacatl.

This mask is likely similar to the one crafted from the thigh skin of the ixiptla (1) during the celebration of Ochpaniztli (Seler etal 1904). This festival, held in the eleventh month of the calendar, involved the ritual cleaning of all buildings in Tenochtitlan to make the city pure. The climax of the festival was the sacrifice of a young woman. This young woman was paraded through the streets and led to the main pyramid. At the pyramid, she was laid on a slab facing the sky, had her mouth bound so she could not scream and she was sacrificed by having her head slowly sawed off by using an obsidian knife as she lay bound on the altar. Then, still in darkness and silence, and with urgent haste, her body was flayed (2), and a naked priest, a ‘very strong man, very powerful, very tall’, struggled into the wet skin (3). The skin of one thigh was reserved to be fashioned into a face-mask for the man impersonating Centeotl, Young Lord Maize Cob

- ixiptla (or teoixiptla) is the name given to the person who is used as a representation of a particular God. This person would (generally) spend time being treated quite royally (sometimes for as long as a year) before being used as a sacrifice in place of the god being represented. See Amaranth and the Tzoalli Heresy for more information on non-human ixiptla

- the body is carefully skinned so as to be able to remove the skin in one piece

- if you’ve ever tried to don a wet wetsuit you get some idea of how difficult this might be. you are also having to take extreme care as you do not want to tear your ‘suit” as you don it. Ick.

Study continues…….

References

- Cabada-Aguirre P, López López AM, Mendoza KCO, Garay Buenrostro KD, Luna-Vital DA, Mahady GB. Mexican traditional medicines for women’s reproductive health. Sci Rep. 2023 Feb 16;13(1):2807. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-29921-1. PMID: 36797354; PMCID: PMC9935858.

- Clendinnen, Inga (1995). Aztecs: An Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- de Orduña, Santiago. (2008) Coatepec: the Great Temple of the Aztecs “Recreating a metaphorical state of dwelling” : School of Architecture, McGill University, Montreal, January 2008

- Froese, Tom. (2020). A Mural of Psychoactive Thorn Apples (Datura spp.) in the Ancient Urban Center of Teotihuacan, Central Mexico. Economic Botany, (), –. doi:10.1007/s12231-019-09485-w

- Knab, Dr T.J. and Sullivan, Thelma D : A Scattering of Jades. “Stories, Poems and Prayers of the Aztecs” : 1994: ISBN 0-671-86413-0

- Marion Oettinger, Jr.. (1982). The Lienzo of Petlacala: A Pictorial Document from Guerrero, Mexico. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (New Series), 72(7), 1–71. doi:10.2307/1006358

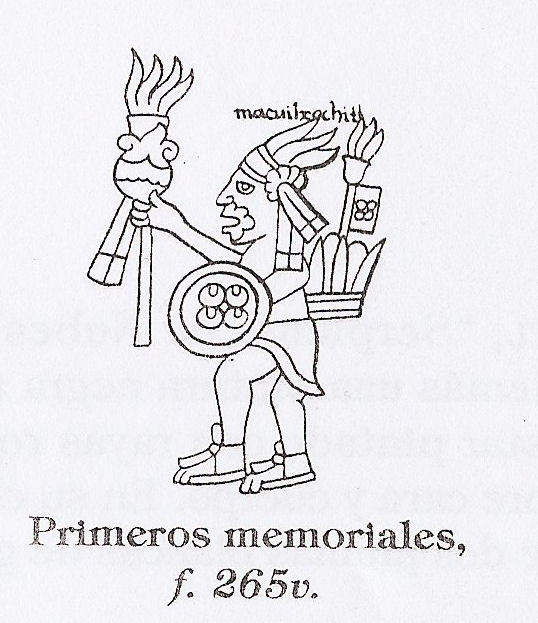

- Sahagún, Bernardino de, Sullivan, Thelma D. Nicholson, H.B., Anderson, Arthur J.O., Dibble, Charles E., Quiñones Keber, Eloise and Ruwet, Wayne (1997) : Primeros Memoriales. (English trans. and paleography of Nahuatl text) Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2909-9.

- Seler, Eduard., Forstemann, E.F., Schellieas, Paul., Sapper, Carl & Dieseldorff, E.R. (1904) MEXICAN AND CENTRAL AMERICAN ANTIQUITIES, CALENDAR SYSTEMS, AND HISTORY : SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION : BUREAU of AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY: W. H. HOLMES, CHIEF : BULLETIN 28

- Seler, Eduard. Collected Works in Mesoamerican Linguistics and Archeology. 2nd ed. Translated by Charles P. Bowditch. Edited by J. Eric S. Thompson and Francis B. Richardson, Frank E. Comparato General Editor. 5 vols. Culver City, CA: Labyrinthos, 1990-2000.

- Vela, Enrique, Arqueología Mexicana Especial Núm. 96 “18. Xochipilli. Tlalmanalco, State of Mexico”, (Mexican Archaeology , special edition no. 96), p. 46-47.

- Wasson, R. Gordon (1974) The Role of ‘Flowers’ in Nahuatl Culture: A Suggested Interpretation, Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 6:3, 351-360, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.1974.10471987

- Wasson R. Gordon. 1980. The Wondrous Mushroom : Mycolatry in Mesoamerica. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Websites

- https://arqueologiamexicana.mx/mexico-antiguo/18-xochipilli-tlalmanalco-estado-de-mexico

- Aquilotl – https://nahuatl.wired-humanities.org/content/aquilotl

- Aquilotl: “water shoot”; jasmine flower; Philadelphus mexicanus – https://xochipilliuniversomexica.inah.gob.mx/en/glosario.html

- Fernández, Justino. “Una Aproximacion A Xochipilli.” Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 1 (1959): http://www.historicas.unam.mx/publicaciones/revistas/nahuatl/pdf/ecn01/004.pdf.

- Mayan ear stretching – https://ctsciencecenter.org/blog/experiencing-maya-hidden-worlds-revealed-maya-body-modifications/

- Mexayacatl – https://www.malinal.net/lexik/nahuatlM.html#MEXAYACATL

Muy interesante análisis. Gracias.

LikeLike

hi, great article! If it’s alright I wanted to share some small, quick notes.

The first is that “elote” is derived from “ēlōtl,” not “xīlōtl.” The two words refer to different stages of corn’s growth, a xīlōtl (“jilote” in Spanish) is tender green corn, lacking kernels, and an ēlōtl (elote) is a young ear of corn that has kernels.

“orejera” is a translation for “ear plug,” ie a nacochtli, not an earmuff.

As far as I’m aware, the Aztecs were arguably prudish regarding body modification compared to their neighbors, such as the Huastecs and the Mayas. They did not practice tattooing like the Mayas or Otomí, preferring to use body paints, dyes, and jewelry for status since they preferred a “clean body.”

Lastly, the ring of xīlōxōchitl around the throne looks to me like it could also be a ring of jades, or chālchihuitl glyphs!

LikeLike

Thank you for this. Research is an ongoing process and is filled with many rabbit holes that require exploration. The comment regarding chalchihuites is very interesting (and oddly very relevant) as I am looking into that right now for another Post. The comments on body modification also need further study as I have found that there are differences between using rods, plugs and spools in the ears and that there is a “class” structure involved in their use. The use of body modification amongst the Mexica (Azteca) also requires a deeper exploration as I am reading right now about nasal piercing (in particular the septum) and ornamentation amongst the Mexica and how certain piercings and ornaments were particular to the ruling classes (and possibly even restricted to the Tlatoani alone) and that there were ceremonies involving nasal piercing when a ruler was inducted into power as a symbol of their elevation to power and their right to rule. Thank you once again. Research continues.

LikeLike